Acts

∞

A Visible Sign

This morning my wife, my kids, and I sat around the Christmas tree and opened the gifts we gave one another. Just as we were finishing, my wife's phone rang.

One of her parishioners was coming down from a bad high in a bad way. The police were on the scene, and the whole family was understandably distressed.

I don't know many details, because as a priest she has to keep confidences. All I know is that her parishioners were asking for her to come and help before things got out of hand.

I don't know many details, because as a priest she has to keep confidences. All I know is that her parishioners were asking for her to come and help before things got out of hand.

Which raises the question, "How can a minister possibly help?" She hasn't got a badge or a gun, so she can't arrest people and lock them up; she doesn't have a medical license, so she can't prescribe medications; she isn't a judge who can order someone to be placed in protective custody.

All she can do is be present with those who are suffering. She can listen to those to whom no one else will listen. She can pray with them, helping to connect those who are suffering with words to express that suffering. She can deliver the sacrament, a visible and outward sign of indelible connection to a bigger community, reminding the lonely that they are not alone.

She quickly got out of her pajamas, put on a black shirt and her clerical collar, and picked up her Book of Common Prayer. I kissed her before she went out the door, aware that she was going to a home where there was a troubled family, a belligerent drug user, and eight armed men charged with upholding the law. Oh, boy. "Do you want some company?" I asked, knowing there wasn't much I could offer besides that. She said she'd be fine.

As she left, and the kids continued to examine their gifts, I sat and silently prayed (reluctantly, as always), joining her in her work in that small way.

I admit that I do not like church. I can think of far pleasanter ways to spend my Sunday morning than leaving my house to stand, and sit, and kneel with a hundred relative strangers.

But this is one thing I love about churches: this deeply democratic commitment to including everyone in the community. No one is to be left out. No one gets more bread or more wine at the altar. Everyone who needs solace, or penance, or forgiveness, or company, may have it.

The Book Of The Acts Of The Apostles, the fifth book of the Greek testament, tells the story of the early church as a place where people who needed food or money or other kinds of sustenance could come and find them. Early on in that book we even see the story of how the church made a special office for people whose job it would be to oversee the equitable distribution of food to the poor.

I think highly of my own profession of teaching, because I think it serves a high social good. But I teach in a small, selective liberal arts college. Most of the people I serve have their lives pretty much together. In general, they can pay their bills, they don't have huge drug or legal issues, they have supportive communities, they can think and write well. Yes, most of them struggle with money and other things, but they keep their heads above water, and their futures are bright.

My wife, on the other hand, has a much broader "clientele." She serves the congregations at our cathedral and several other parishes. Her congregants range from the powerful and wealthy to the poorest of the poor. Here in South Dakota more than half our diocese are Native Americans, and many more are refugees from conflicts in east Africa. Ethnically, racially, economically, liturgically, and politically, this is a diverse group.

And again, it is a group where everyone is - or at least ought to be - welcome.

The church has always failed to live up to its ideals. I don't dispute that. Show me an institution that has good ideals and that always lives up to them, and I'll readily tip my hat to it. What I love in the church is that it has these ideals and it has daily, weekly, and annual rituals by which we remind ourselves what those ideals are. We screw them up, we distort and bastardize them, we even sell them to high bidders from time to time when we lose our heads and our hearts. But then we remind ourselves that we should not. And we have institutions and rituals of returning to the path we've departed from.

We will probably always get it wrong. I'm okay with that, as long as we keep turning back towards what is right, as long as we maintain these traditions and rituals of self-examination and self-correction. And as long as we cherish this ideal of welcoming everyone, absolutely everyone. I don't mean just saying we welcome everyone, but I mean doing it.

Again, I work at a small college. Colleges are places where we all talk a good game about being welcoming, and for the most part, we manage to practice what we preach, given the communities we work in. But there's something really remarkable about seeing that ideal at work in a community where there are no grades and no graduation, where the congregation is not just 18-22 year-olds with high entrance exam scores, and where no one gets kicked out for failure to live up to the ideals of the place.

Last night we celebrated Christmas with hymns in two languages.

My wife came home a hour or so after she left this morning. I don't worry so much about her sudden comings and goings as I once did. She gets calls late at night from broken-hearted families watching their beloved die in our hospitals. Will she come and pray with them? Will she come hold their hands for a little while, and be the vicarious presence of the whole church as they suffer? Will she anoint the sick as a reminder of our shared hope for well-being for all people? Will she come to the jail to talk with the kid who has just been arrested, or to sit with his frightened parents? Will she come to the nursing home where they're wondering if this is the last holiday a grandparent will see?

Yes, she will. This is her calling, the work she has been ordained to do. It is the work of love, and I love her for it.

As she walked in the door, I was going to greet her when her phone rang again. I recognized from her conversation that it is a parishioner with memory problems who calls her almost every day to ask the same questions. Sometimes it seems he has been drinking; most of the time it seems he is lonely and afraid. I knew my greeting could wait, and as she patiently listened to her parishioner, I joined her in silent prayer, thanking God for the kindness she shows and represents, a visible sign of the ideal of our community. She cheerfully wished him a Merry Christmas. I think she was glad he knew what day it was.

I don't know how she does it, but she makes me want to keep trying.

One of her parishioners was coming down from a bad high in a bad way. The police were on the scene, and the whole family was understandably distressed.

I don't know many details, because as a priest she has to keep confidences. All I know is that her parishioners were asking for her to come and help before things got out of hand.

I don't know many details, because as a priest she has to keep confidences. All I know is that her parishioners were asking for her to come and help before things got out of hand.Which raises the question, "How can a minister possibly help?" She hasn't got a badge or a gun, so she can't arrest people and lock them up; she doesn't have a medical license, so she can't prescribe medications; she isn't a judge who can order someone to be placed in protective custody.

All she can do is be present with those who are suffering. She can listen to those to whom no one else will listen. She can pray with them, helping to connect those who are suffering with words to express that suffering. She can deliver the sacrament, a visible and outward sign of indelible connection to a bigger community, reminding the lonely that they are not alone.

She quickly got out of her pajamas, put on a black shirt and her clerical collar, and picked up her Book of Common Prayer. I kissed her before she went out the door, aware that she was going to a home where there was a troubled family, a belligerent drug user, and eight armed men charged with upholding the law. Oh, boy. "Do you want some company?" I asked, knowing there wasn't much I could offer besides that. She said she'd be fine.

As she left, and the kids continued to examine their gifts, I sat and silently prayed (reluctantly, as always), joining her in her work in that small way.

I admit that I do not like church. I can think of far pleasanter ways to spend my Sunday morning than leaving my house to stand, and sit, and kneel with a hundred relative strangers.

But this is one thing I love about churches: this deeply democratic commitment to including everyone in the community. No one is to be left out. No one gets more bread or more wine at the altar. Everyone who needs solace, or penance, or forgiveness, or company, may have it.

The Book Of The Acts Of The Apostles, the fifth book of the Greek testament, tells the story of the early church as a place where people who needed food or money or other kinds of sustenance could come and find them. Early on in that book we even see the story of how the church made a special office for people whose job it would be to oversee the equitable distribution of food to the poor.

I think highly of my own profession of teaching, because I think it serves a high social good. But I teach in a small, selective liberal arts college. Most of the people I serve have their lives pretty much together. In general, they can pay their bills, they don't have huge drug or legal issues, they have supportive communities, they can think and write well. Yes, most of them struggle with money and other things, but they keep their heads above water, and their futures are bright.

My wife, on the other hand, has a much broader "clientele." She serves the congregations at our cathedral and several other parishes. Her congregants range from the powerful and wealthy to the poorest of the poor. Here in South Dakota more than half our diocese are Native Americans, and many more are refugees from conflicts in east Africa. Ethnically, racially, economically, liturgically, and politically, this is a diverse group.

And again, it is a group where everyone is - or at least ought to be - welcome.

The church has always failed to live up to its ideals. I don't dispute that. Show me an institution that has good ideals and that always lives up to them, and I'll readily tip my hat to it. What I love in the church is that it has these ideals and it has daily, weekly, and annual rituals by which we remind ourselves what those ideals are. We screw them up, we distort and bastardize them, we even sell them to high bidders from time to time when we lose our heads and our hearts. But then we remind ourselves that we should not. And we have institutions and rituals of returning to the path we've departed from.

We will probably always get it wrong. I'm okay with that, as long as we keep turning back towards what is right, as long as we maintain these traditions and rituals of self-examination and self-correction. And as long as we cherish this ideal of welcoming everyone, absolutely everyone. I don't mean just saying we welcome everyone, but I mean doing it.

Again, I work at a small college. Colleges are places where we all talk a good game about being welcoming, and for the most part, we manage to practice what we preach, given the communities we work in. But there's something really remarkable about seeing that ideal at work in a community where there are no grades and no graduation, where the congregation is not just 18-22 year-olds with high entrance exam scores, and where no one gets kicked out for failure to live up to the ideals of the place.

Last night we celebrated Christmas with hymns in two languages.

Hanhepi wakan kin!That's the second verse of "Silent Night, Holy Night," from the Dakota Episcopal hymnal. We sing the doxology in Dakota, and I'm happy to say that most of the white folks at several congregations in the area have it memorized in Dakota. These are small things, but they might also be big things. If the baby Christ was the Word incarnate, surely little words can make a big difference.

Wonahon wotanin

Mahpiyata wowitan,

On Wakantanka yatanpi.

Christ Wanikiya hi!

My wife came home a hour or so after she left this morning. I don't worry so much about her sudden comings and goings as I once did. She gets calls late at night from broken-hearted families watching their beloved die in our hospitals. Will she come and pray with them? Will she come hold their hands for a little while, and be the vicarious presence of the whole church as they suffer? Will she anoint the sick as a reminder of our shared hope for well-being for all people? Will she come to the jail to talk with the kid who has just been arrested, or to sit with his frightened parents? Will she come to the nursing home where they're wondering if this is the last holiday a grandparent will see?

Yes, she will. This is her calling, the work she has been ordained to do. It is the work of love, and I love her for it.

As she walked in the door, I was going to greet her when her phone rang again. I recognized from her conversation that it is a parishioner with memory problems who calls her almost every day to ask the same questions. Sometimes it seems he has been drinking; most of the time it seems he is lonely and afraid. I knew my greeting could wait, and as she patiently listened to her parishioner, I joined her in silent prayer, thanking God for the kindness she shows and represents, a visible sign of the ideal of our community. She cheerfully wished him a Merry Christmas. I think she was glad he knew what day it was.

I don't know how she does it, but she makes me want to keep trying.

∞

The Purpose of Profits

Today I spoke with a young entrepreneur I know. He has built a thriving business that provides income for half a dozen people, and now he is thinking about what to do with his business. His plan, he says, is to use it as a source of income for non-profits.

This entrepreneur -- let's call him Tom* -- believes that the purpose of profit is to do good for others. He seems to be a deeply religious man, and he sees this as a way of sharing the gifts he has received from God with others. Says he doesn't see why any CEO needs to make more than enough, which he defines as being about $70,000 a year.

Tom is one of those people who make me pause and reconsider my own financial goals, hopes, and fears. When I think about investing and saving, I admit I'm worried about not having enough someday. What if I lose my job, or suffer an injury that keeps me from working? Will we have enough for us to provide for our kids and to retire on?

Tom's view is peculiar: he would rather have a rich community than a rich savings account. He's trying to embody the lesson of the "parable of the unjust manager," who decided it was better to have friends than money; or of the stories of the early church in the Book of Acts. If I remember right, those stories inspired Karl Marx as well.

My friend Tom is no St Francis, and he's not taking a vow of poverty. He's just drawing a line and refusing to let the clamor of financial fear drown out the song of hope. Like so many religious people, his hopes are as extravagant as they are counter-cultural. And they're prophetic, at least in the way Cornel West uses that word. At least, that's what I heard in Tom's story today: he wants to do good with his money, and some of that good will be reminding us that fear is not a good master.

A few years ago a friend who taught in the business school at Penn State was engaged in a study of businesses that were trying to bring together the ideals of for-profits and non-profits - businesses like Nutriset - that were trying to generate profits by producing good things at reasonable prices. I have to say that dreaming about this way of combining capitalism and social good inspires me.

*I'm not giving out his name or his business name because I don't want to cause him to be flooded with funding requests.

This entrepreneur -- let's call him Tom* -- believes that the purpose of profit is to do good for others. He seems to be a deeply religious man, and he sees this as a way of sharing the gifts he has received from God with others. Says he doesn't see why any CEO needs to make more than enough, which he defines as being about $70,000 a year.

|

| Can't buy me love. |

Tom is one of those people who make me pause and reconsider my own financial goals, hopes, and fears. When I think about investing and saving, I admit I'm worried about not having enough someday. What if I lose my job, or suffer an injury that keeps me from working? Will we have enough for us to provide for our kids and to retire on?

Tom's view is peculiar: he would rather have a rich community than a rich savings account. He's trying to embody the lesson of the "parable of the unjust manager," who decided it was better to have friends than money; or of the stories of the early church in the Book of Acts. If I remember right, those stories inspired Karl Marx as well.

My friend Tom is no St Francis, and he's not taking a vow of poverty. He's just drawing a line and refusing to let the clamor of financial fear drown out the song of hope. Like so many religious people, his hopes are as extravagant as they are counter-cultural. And they're prophetic, at least in the way Cornel West uses that word. At least, that's what I heard in Tom's story today: he wants to do good with his money, and some of that good will be reminding us that fear is not a good master.

A few years ago a friend who taught in the business school at Penn State was engaged in a study of businesses that were trying to bring together the ideals of for-profits and non-profits - businesses like Nutriset - that were trying to generate profits by producing good things at reasonable prices. I have to say that dreaming about this way of combining capitalism and social good inspires me.

*****

*I'm not giving out his name or his business name because I don't want to cause him to be flooded with funding requests.

∞

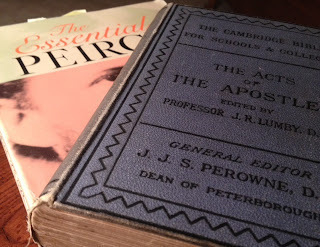

Pragmatist Scripture: Peirce and The Book of Acts

A few months ago a friend who is interested in both scripture and philosophy asked me which scripture mattered most to Charles Peirce. One obvious answer would be the writings of John, the gospeller of agape love, since agape plays such a great role in Peirce's philosophy.

The Book of Acts has recently come to mind as another strong candidate, for several reasons. I plan to write about all this in more detail soon, but I'll use this space to jot down my thinking quickly, in order to make it available to anyone who might be interested, in the Peircean spirit of shared inquiry.

The Greek title of the Book of Acts is Praxeis Apostolon, or the Deeds of the Apostles. We guess that the author of the text was the same as the author of the Gospel attributed to Luke. The title might well have been added after the book was in circulation for a while, but that's probably inconsequential. It occurred to me recently that this text begins with reminding us that the author wrote a previous book about "the things Jesus began to do and to teach," and then it narrates, without further introduction, the things that the first Christians did after Jesus' death and resurrection.

In other words, it is a book of acts, of deeds. It is a book of narratives about what people did.

Which is to say that it is not primarily a book of prayers, or of songs, or of doctrines. It tells a story, without much attempt to interpret that story. And it is the story of a community learning to work together, and learning how it must adjust its doctrines in light of the community's expansion across and into cultures, and in light of the surprising things they find the new community is empowered to accomplish.

This is appealing to Pragmatists like Peirce, who are more concerned with the way decisions lead to actions than with fixing metaphysical doctrines and whose notions of truth, ethics, and metaphysics are more experimental and transactional than systematic and permanent. Pragmatists are given to the idea that it is good for communities to work with tentative, revisable and fallible tenets, ever striving to improve their practices as the community grows.

*****

Peirce is not exactly easy to read, which helps to explain why most of what he wrote remains unpublished even a century after his death. Nevertheless, the patient reader of Peirce is often rewarded by a writer who took words very seriously.

Some of the words he used to great effect in his lectures and essays are derived from the Book of Acts. Among these phrases are a phrase he uses in his 1907 essay "A Neglected Argument For The Reality Of God," and one that comes at the end of his Cambridge Conference Lectures of 1898. The phrases are "scientific singleness of heart," and "things live and move and have their being in a logic of events." See Acts 2.46 and 17.28 for the sources of these two phrases. (The first one might also have come to Peirce through the Anglican Book of Common Prayer, as I have argued elsewhere.)

Two such phrases are not enough to make the case that Peirce was dependent on the Book of Acts, but thankfully that's not the case I'm trying to make. Peirce was well read and he cited other portions of scripture and, of course, many other books, after all. I only want to suggest that Peirce might have found the Book of Acts to be a scripture that resonates with his Pragmatism.

*****

That being said, I wish to point to one figure in the middle of the Book of Acts who might be taken to be a kind of Pragmatist saint: Epimenides.

I won't belabor that point here, as I have already written about it elsewhere. I'll only add that Epimenides appears to be the unnamed source that St Paul appeals to and cites in Acts 17.28.

The Book of Acts has recently come to mind as another strong candidate, for several reasons. I plan to write about all this in more detail soon, but I'll use this space to jot down my thinking quickly, in order to make it available to anyone who might be interested, in the Peircean spirit of shared inquiry.

The Greek title of the Book of Acts is Praxeis Apostolon, or the Deeds of the Apostles. We guess that the author of the text was the same as the author of the Gospel attributed to Luke. The title might well have been added after the book was in circulation for a while, but that's probably inconsequential. It occurred to me recently that this text begins with reminding us that the author wrote a previous book about "the things Jesus began to do and to teach," and then it narrates, without further introduction, the things that the first Christians did after Jesus' death and resurrection.

In other words, it is a book of acts, of deeds. It is a book of narratives about what people did.

Which is to say that it is not primarily a book of prayers, or of songs, or of doctrines. It tells a story, without much attempt to interpret that story. And it is the story of a community learning to work together, and learning how it must adjust its doctrines in light of the community's expansion across and into cultures, and in light of the surprising things they find the new community is empowered to accomplish.

This is appealing to Pragmatists like Peirce, who are more concerned with the way decisions lead to actions than with fixing metaphysical doctrines and whose notions of truth, ethics, and metaphysics are more experimental and transactional than systematic and permanent. Pragmatists are given to the idea that it is good for communities to work with tentative, revisable and fallible tenets, ever striving to improve their practices as the community grows.

*****

Peirce is not exactly easy to read, which helps to explain why most of what he wrote remains unpublished even a century after his death. Nevertheless, the patient reader of Peirce is often rewarded by a writer who took words very seriously.

Some of the words he used to great effect in his lectures and essays are derived from the Book of Acts. Among these phrases are a phrase he uses in his 1907 essay "A Neglected Argument For The Reality Of God," and one that comes at the end of his Cambridge Conference Lectures of 1898. The phrases are "scientific singleness of heart," and "things live and move and have their being in a logic of events." See Acts 2.46 and 17.28 for the sources of these two phrases. (The first one might also have come to Peirce through the Anglican Book of Common Prayer, as I have argued elsewhere.)

Two such phrases are not enough to make the case that Peirce was dependent on the Book of Acts, but thankfully that's not the case I'm trying to make. Peirce was well read and he cited other portions of scripture and, of course, many other books, after all. I only want to suggest that Peirce might have found the Book of Acts to be a scripture that resonates with his Pragmatism.

*****

That being said, I wish to point to one figure in the middle of the Book of Acts who might be taken to be a kind of Pragmatist saint: Epimenides.

I won't belabor that point here, as I have already written about it elsewhere. I'll only add that Epimenides appears to be the unnamed source that St Paul appeals to and cites in Acts 17.28.