道

I’ve been requiring my students to take notes on paper for our classical Asian philosophies class. This is partly because I am teaching them some key vocabulary in both Sanskrit and Classical Chinese, and I want them to learn the strokes for the characters. Many of them have bought brush pens or calligraphy pens, and their notes are turning into works of art. It’s fun to watch this happen!

Building Benches

Another page from my notebook. This one is a dream page of some trail furniture I have built and some I am planning to build. How do I make a chair out of wood that will eventually rot into the ground without leaving behind too much synthetic chemical residue? What waste wood can I use to build it? How can I make trails more accessible to folks who might want someplace to sit and rest their knees while they listen to the birdsong? Etc.

Herodotus in my Pocketbook

I carry notebooks with me everywhere.

Sometimes they’re for new thoughts.

Often they’re for very old ones.

I was recently in our university library (use it or lose it!) spending time with some of the Greek classics of historiography. I probably pulled forty books from the shelves, most of them in Greek, most of them too expensive for me to own copies of, most of them rarely visited and quite hard to find online or in digital form.

And I took notes. I had my laptop, so I typed some notes. I also took notes with pen and ink, a stable and durable form of note-taking. One that allows me to sketch, and that makes it easy to switch between languages.

Here’s one classic piece I jotted down. Not because I needed to, but because I could, and because the slow process of jotting notes lets the words seep into my muscles and neurons, lets them become a part of my being.

“Have you pen and ink, Master Doctor?”

“A scholar is never without them, your Majesty,” answered Doctor Cornelius.

– C.S. Lewis, Prince Caspian, ch. 13

A friend who has meant a lot to me over the years recently posted a photo of himself. I took some time to sketch the image, not just once but several times. He lives far away and I rarely see him now, but it felt good to let my pen imagine him nearby on paper.

Dewi Sant

Happy St David’s Day! Mom used to call us all on March 1 to remind us of our ancestry. She would remind her youngest child that he was named for the patron saint of her ancestors. And she would look for the daffodils that might soon be rising above the melting frost in her garden.

My first visit to Wales was while I was studying abroad in college. I took a train to the coast and stood on a cliff overlooking the sea in December. The town nearby was quiet, the wind lashed my face with biting drops of cold rain and seawater torn from the tops of waves. The sky was the color of slate from one horizon to the other.

And I felt like my feet could sink down into that rocky soil and become rooted, forever at home in that place. Some ancestral memory, perhaps? A sense of pride and connection with my family who have lived there since time immemorial? Or just the longing of a teenager to feel connected to something bigger than himself? Who can say.

I know that I also look for the daffodils’ defiance of winter’s grasp, and its announcement of warmth and color and blooming, buzzing life.

I know that I hang the flag as a remembrance of my mother and grandparents, looking forward to seeing them again with fresh soul-eyes.

I know that Dewi Sant, or Saint David, reminds me that the little things often matter very much, and the little lives need tendance.

“Gwnewch y pethau bychain mewn bywyd.”

Do the little things.

Tend the small lives.

Watch for the daffodils.

And when you see them rise, point to them and show someone you love. “Look,” you might say, since that can be one of the kindest words when pointing to small, not-yet-noticed beautiful things that are just rising to bloom.

Brothers

Working on drawing people, especially hands, faces, and motion. After a recent wrestling event on campus my friend’s young boys hit the mats in their puffy winter coats and, as brothers often do, grappled and tussled on the floor. This morning’s sketch is from a photo I took as they practiced their skills in fraternal love and competition.

If you click on the alt text you’ll see that the AI generated text describes this as a sketch of a “comforting embrace.” Since they are twin brothers who love to wrestle, it could be that this is what true comfort looks like for them.

Coffee shop seminar notes.

Today’s shelfie. Lots of meetings, fewer books.

My day in books. Today’s shelfie.

Asphodel in Tiryns

One more morning Greece-themed sketch: asphodel flower. (Asphodelus ramosus)

I photographed this one on the ruins of Tiryns, not far from Nauplion, in Greece. These are some places I love to visit. Nauplion is worth visiting for its own sake. Many who go there of course visit Mycenae and Epidaurus, and the Palamidi fortress and other major archeological sites, but Tiryns and Lerna are nice because so few tourists visit them. They’re quiet, surrounded by orange groves, with the smell of the sea in the air.

The asphodel is associated with gravesites, and with the underworld, and with memory of the dead. Some have said it can heal snakebites (I don’t recommend testing this theory without a backup plan.)

I associate it with Greece, a country full of gentle blossoms.

Delphi Treasury

Part of my morning discipline: get a little better at sketching and painting every day.

I’ll be taking students to Greece again in a few weeks, so I’m going over some photos from previous trips and thinking about color and light.

Is any sky so blue as in Greece? Maybe, but the blue skies there are painted on the walls of my heart’s restful chambers.

Contemplation

Cal Newport asks, in the Chronicle of Higher Education, whether email is making professors stupid. Frictionless communication comes at the expense of long stretches of uninterrupted thought. Some of the practices that make me a better scholar and teacher:

- writing letters by hand;

- walking (strolling, perambulating, sauntering—not merely moving my body to the next meeting) outdoors;

- reading deeply and broadly;

- carrying paper and pen, and taking notes, and then reflecting on those notes and refining them later;

- making time for art;

- prayer, singing, worship;

- contemplation, conversation, and commentary. I’m not aiming for what is so often vaunted as “efficiency.” I am far more interested in doing a few things well. (Vaunting afterwards, or during, is optional, and need not be online.)

My friends often hear me return to this word “contemplation.” I think of it as what precedes good conversation. The word can sound antiquated and slow in an age that cherishes speed. But some things shouldn’t be rushed.

The word has echoes of time in a temple, in a sacred space that invites us to move slowly, to consider our smallness in a great cosmos. The columns of a cathedral draw one’s gaze upwards like boles of ancient trees. The act of looking up slows our feet, and even helps us to stand still, lest we tumble into a well like ancient Thales.

The street outside, the space outside the temenos, can bustle on. It will still buzz and hum when we return to it. For now, read slowly. Drink deeply. Listen quietly. All of this is preparation. It looks like inefficiency because you are not moving fast. But the best runners take time to prepare their muscles for the race, and while they are preparing they are often still. To run without ceasing is not efficient; it is self-defeat.

We will all devote ourselves to something. Something will be the object of our affection. That affection will be shown by how we inhabit the moments of our days, (by how, as we often say, we “spend” our limited allotment of time.) Worship—acknowledging something as worthy of our time and attention, or worth-ship— is not optional. The only choice is who and what receives our attention.

Dorothea, and you, and me

Here are the final words of Middlemarch, words I have often returned to:

“Her finely-touched spirit had still its fine issues, though they were not widely visible. Her full nature, like that river of which Cyrus broke the strength, spent itself in channels which had no great name on the earth. But the effect of her being on those around her was incalculably diffusive: for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.”

Eliot touches on this earlier in her book as well. Here is a passage from chapter 41:

“Who shall tell what may be the effect of writing? If it happens to have been cut in stone, though it lie face downmost for ages on a forsaken beach, or “rest quietly under the drums and tramplings of many conquests,” it may end by letting us into the secret of usurpations and other scandals gossiped about long empires ago: —this world being apparently a huge whispering-gallery. Such conditions are often minutely represented in our petty lifetime. As the stone which has been kicked by generations of clowns may come by curious little links of effect under the eyes of a scholar, through whose labours it may at last fix the date of invasions and unlock religions, so a bit of ink and paper which has long been an innocent wrapping or stop-gap may at last be laid open under the one pair of eyes which have knowledge enough to turn it into the opening of a catastrophe. To Uriel watching the progress of planetary history from the Sun, the one result would be just as much of a coincidence as the other. Having made this rather lofty comparison I am less uneasy in calling attention to the existence of low people by whose interference, however little we may like it, the course of the world is very much determined.”

Sometimes there are people who are “low people” — mean, cruel, selfish, unkind — whose actions and words add up to horrible things that should be beyond the power of any one person to bring about. The little things, like little seeds, can grow into very big things.

I remain hopeful that even where there are tyrants and would-be tyrants, in the long run it is the steadfastly kind person, the one who knows that “all flourishing is mutual,” the prayerful pastor standing in the streets to be arrested on behalf of the downtrodden, the prayerful grandmother alone in the small dark hours, the person who offers an encouragement to someone who needs it right now, the faithful hobbit—the people who seem unimportant to the writers of history and to the halls of power—who are steadily building a better future for others.

I don’t mean to say everything is working out fine, just be patient. I do mean to say that when I wonder whether that cup of tea and half an hour of my time offered to a crying student really makes a difference, especially when I have reports due and meetings to attend, etc; when I wonder about all of that, words like Eliot’s remind me why I do what I do, and encourage me to keep trying. I won’t save the world, but I can make it better for some of those who come after me.

And so can you.

—George Eliot, Middlemarch

Often when we write — and especially when we write by hand, the slow work of pen on paper — words and ideas come forth that we did not yet know were latent within us.

Our souls are word-seed banks full of years-old seeds awaiting the light of day.

Today’s shelfie. Books that came off the office shelves for the purpose of teaching and in conversation with students. A good day, and a full one.

Sent a book manuscript to my publisher today and it feels really good. Now on to the next book!

The Deer Mouse, The Mountain, and The Road to Mastery

Deer mouse on our bird feeder yesterday, and sketched in my journal.

The mouse-sketch came after writing about two books I’ve read this past week, Nicholas Triolo’s The Way Around, and Gary Snyder’s Mountains and Rivers Without End.

Triolo mentions Snyder, in particular his poem about “The Circumambulation of Mt Tamalpais,” in his book—which is also about circumambulation and which makes explicit reference to Snyder’s poem.

After reading these two books I started writing some stream-of-consciousness poetry about where our clean water comes from and where it goes. These are things I think we don’t pay enough attention to.

After writing that poem as a draft I returned to it to see if there was anything good in it. (Sometimes there is! But not always.)

I found in it the inkling of a haiku, so I wrote the draft of the haiku several times.

Each draft was poor, awkward, clumsy.

Which is fine.

You don’t suddenly become a master of haiku.

You get better by trying, failing, observing, reading, watching others at work, getting criticism, trying again.

Ora et labora. Repeat.

Try. Err. Stumble. Pray. Try again. Pray again.

Try with rigor and with periods of rest.

Contemplation, conversation, commentary.

I am not a master of haiku. I have written and published a little poetry but not much.

Lately I have been focusing more on sketching and painting. Observing small lives, small details.

So after the poem I returned to the mouse.

Normally I begin my sketches with pencil. Maybe non-photo blue, or light graphite. Then I can erase the sketch once I have gone over the best parts with ink.

But I have been practicing a lot, and this week I have often begun my sketches with ink.

I am not a master, but after lots of practice I worry less that this sketch will fail. As Henry Bugbee says, “get it down.”

So I am getting it down. If I mess up (I will!) I will repeat. Or try another.

And I will keep learning.

The road to mastery is not a day trip.

It is “a long obedience in the same direction.”

But I am learning that the road itself, even if I never complete the walk, is beautiful every step of its circumambulatory and peripatetic way.

For the Grandchildren

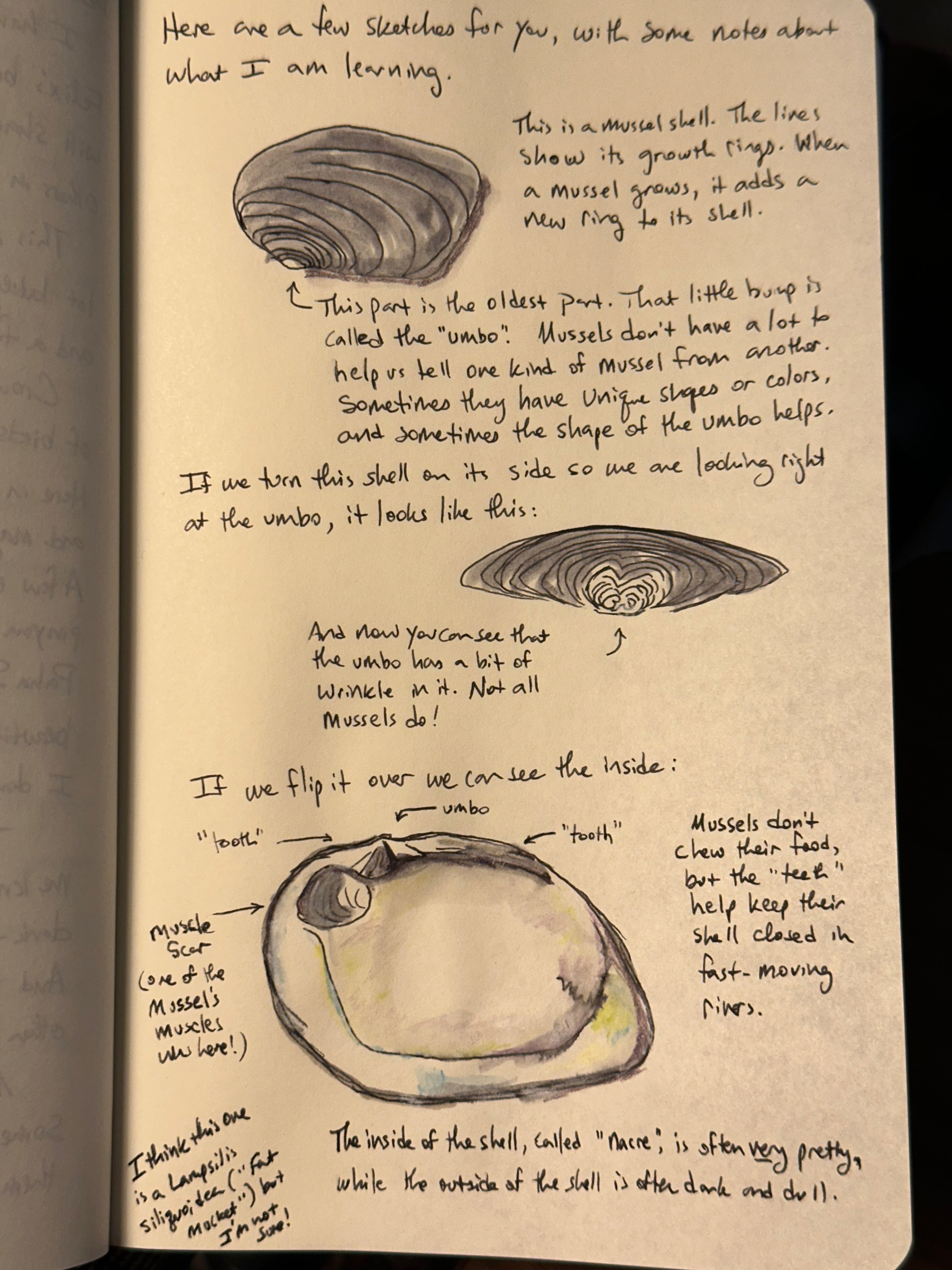

Each week I try to write something in the books I am making for my grandchildren.

Sometimes I tell them stories about the family.

Other times I tell them what I am learning and seeing in the world.

They’re very young, so I haven’t the heart to tell them in these books all that I am seeing. I’m writing that elsewhere, for when they are older.

For now I am trying to share the good and the beautiful and do speak truth in love, hoping that it will make a difference for them as they do the hard work of loving their neighbors as themselves. All their neighbors.

I often think of Gary Snyder’s poem, “For the Children.”

I share that one with my students pretty often, especially when we are spending a week trekking through the rainforest or across the tundra.

Those last words keep ringing in my ears:

“Stay together / Learn the flowers / Go light.”

These are things we all need, I think.

So I am sharing the little I have, and hoping that it will grow.

Corvids

A morning corvid sketch.

I once asked someone named Crow how they got their name.

They replied “It’s a cool bird.”

I thought that was a pretty good answer.