Alaska

- Henry Bugbee, The Inward Morning. Don't try to read this book quickly, and if you're not prepared to do the hard work of thinking, move on and read something else. But if you're willing to read slowly and thoughtfully, this book can change your life. Bugbee was a philosophy professor and an angler.

- Henry David Thoreau, A Week On The Concord and Merrimack Rivers; The Maine Woods. Thoreau was an occasional angler, and an observer of anglers.

- Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac and the title essay in The River Of The Mother Of God, about unknown places. Leopold only writes a little about fish and fishing, but those occasional sentences about angling tend to be shot through with insight.

- John Muir, Nature Writings.

- John Steinbeck, Log From The Sea of Cortez. An apology for curiosity, in narrative form. One of my favorite books.

- Paul Errington, The Red Gods Call. Not brilliant writing, but a fascinating set of memoirs from a professor of biology who put himself through college as a trapper, and about how the Big Sioux River in South Dakota was his first real schoolroom. He talks a good deal about hunting and fishing and what he learned through encounters with animals.

- Kathleen Dean Moore, The Pine Island Paradox. Moore is an environmental philosopher who writes winsomely ans insightfully about what nature has meant to her family.

- Nick Lyons. Nick very kindly wrote the foreword to my book, and when I first got in touch with him about this I discovered he and I had lived only a few miles from each other in the Catskill Mountains for years. Sadly, by the time I discovered this I'd already moved away, and he was packing up to move to a new home, too. We both love the miles of small trout streams of those mountains, though. Nick has been a prolific writer and he has promoted a lot of great writing through his lifelong work as a publisher as well. Nick has a new book, Fishing Stories, just published in 2014.

- Norman Maclean, A River Runs Through It

- Ernest Hemingway, especially "Big Two-Hearted River" and the other Nick Adams stories

- James Prosek. Several books, including Trout: An Illustrated History; Early Love And Brook Trout; and Joe And Me: An Education In Fishing And Friendship

- Ted Leeson, The Habit Of Rivers

- Kurt Fausch’s new book, For The Love Of Rivers: A Scientist’s Journey. Brilliant writing by one of the world's leading trout biologists.

- Craig Nova, Brook Trout and the Writing Life. I also like his novels, and will recommend The Constant Heart.

- Christopher Camuto, who writes frequently for Trout Unlimited's journal, Trout.

- Ian Frazier, The Fish's Eye.

- Douglas Thompson, The Quest For The Golden Trout

- Izaak Walton, The Compleat Angler

- Dame Juliana Berners, The Boke Of St Albans, later editions of which contain A Treatyse of Fysshynge with an Angle, possibly authored by someone else.

- Nick Karas, Brook Trout (a nice collection of short works about brook trout, including some of my favorite stories)

- Lee Wulff

- Lefty Kreh

- John Gierach. Gierach has written a lot about angling, so it's not surprising that so many people mention him to me. Many of those mentions are positive, but some anglers mention his name with disgust. I haven't read much of his work, so I can't yet say why.

- David James Duncan, The River Why. This is a fun novel set in the Northwest, but it reminds me of the New Haven River in Vermont: there are some long dry stretches one has to plod through, but repeatedly one comes to depths that make the flatter, shallower parts worthwhile.

- Thomas McGuane, The Longest Silence.

- Bill McMillan

- Roderick Haig-Brown

- Mike Valla, The Founding Flies

- Michael Patrick O’Farrell, A Passion For Trout: The Flies And The Methods

- Peter Reilly, Lakes and Rivers of Ireland

- Derek Grzelewski, The Trout Diaries: A Year of Fly-fishing In New Zealand and The Trout Bohemia: Fly-Fishing Travels In New Zealand

- Eeva-Kaarina Aronen, Die Lachsfischerin. A novel set in Finland, about fly-fishing and fly-tying in the 18th century. The title translates as “The Salmon Fisherwoman”

- Ian Colin James, Fumbling With A Fly Rod (Scotland)

- Zane Grey, Tales of the Angler’s Eldorado: New Zealand

- Leslie Leyland Fields, Surviving the Island of Grace; and Hooked! Fields and her family are commercial fishers in Alaska, and her writing comes recommended to me from a number of sources.

- Sheridan Anderson, The Curtis Creek Manifesto

- Harry Middleton, The Earth Is Enough: Growing Up In A World Of Fly-fishing, Trout, And Old Men (Memoir)

- Paul Schullery, Royal Coachman: The Lore And Legends of Fly-fishing

- Gordon MacQuarrie

- Patrick McManus

- Vince Marinaro, The Game of Nods

- Rich Tosches, Zipping My Fly

- Robert Lee, Guiding Elliott

- Peter Heller, The Dog Stars (novel)

- Paul Quinnett, Pavlov’s Trout

- Dana S. Lamb Where The Pools Are Bright And Deep; Bright Salmon and Brown Trout

- John Shewey, Mastering The Spring Creeks

- Ernest Schweibert, Death of a Riverkeeper; A River For Christmas

- Richard Louv, Fly-fishing for Sharks: An Angler’s Journey Across America

- John Voelker’s short story “Murder”

- Dave Ames, A Good Life Wasted, Or 20 Years As A Fishing Guide

- Craig Childs, The Animal Dialogues, especially the chapter “Rainbow Trout”

- Randy Nelson, Poachers, Polluters, and Politics: A Fishery Officer’s Career

- Anders Halverson, An Entirely Synthetic Fish: How Rainbow Trout Beguiled America And Overran The World

- Thomas McGuane, A Life In Fishing

- Bob White

- Robert Ruark

- Tom Meade

- Hank Patterson

∞

Watching the Fish

I've been publishing some short pieces on Medium lately. It's a way of doing some quick writing about things I've taught about for years.

This latest one is about watching fish, and I hope you enjoy it. Here's a sample:

I love fish. And whenever I say that, most people assume I love either eating fish or catching them. But neither of those is what I mean.

What I mean, more than anything, is that I love watching them at home in the places where they live.

You can find the whole article here.

∞

Bristol Bay and Pebble Mine: Mutual Flourishing or Midas' Touch

My latest article on salmon and mining was just published in Ethics, Policy, & Environment. A proposed gold mine in Alaska offers a lot of financial wealth, but it also poses significant risk of environmental loss to the salmon population downstream, and to everything that depends on the salmon for food.

In this brief commentary I argue that we should prefer long-term mutual flourishing over the prospect of short-term financial gain for a few. The myth of King Midas offers an illustration of what is at risk: the gleam of gold can blind us to the importance of being good stewards of nature, and of being good neighbors and good ancestors:

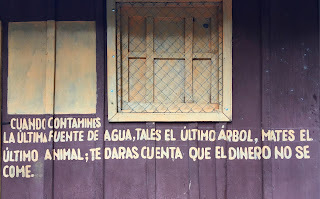

It reads "When you pollute the last source of water, cut down the last tree, and kill the last animal, you'll realize that you can't eat money."

It would be good to learn that lesson before it's too late for the salmon - and for everything that depends upon them.

You can read my article here.

In this brief commentary I argue that we should prefer long-term mutual flourishing over the prospect of short-term financial gain for a few. The myth of King Midas offers an illustration of what is at risk: the gleam of gold can blind us to the importance of being good stewards of nature, and of being good neighbors and good ancestors:

"Not all mining is bad, but to choose a mine that offers gold in exchange for life and mutual flourishing is to display a clear symptom of Midas’ malady. In the ancient myth, King Midas wished for the power to turn all he touched into gold. Half a trillion dollars in ore under the tundra might make us forget what Midas suffered when his wish was granted: he gained great wealth at great cost. When he reached out for food, it turned to inedible gold in his hand. In the case of the Pebble Mine, the risk is not to the PLP, but to the people who are sustained by a four-thousand-year-old tradition of salmon harvesting, and to all the other birds, animals, and plants that depend upon the salmon."I'm reminded of a hand-painted sign I recently came across at a ranger station in El Zotz in Guatemala's Maya Biosphere Reserve.

It reads "When you pollute the last source of water, cut down the last tree, and kill the last animal, you'll realize that you can't eat money."

It would be good to learn that lesson before it's too late for the salmon - and for everything that depends upon them.

You can read my article here.

∞

Teaching Tropical Ecology in Belize and Guatemala

Two out of every three January terms my colleague Craig Spencer and I teach a course on tropical ecology in Central America. Right now I'm in the midst of preparing for our next trip there.

In this post I'll try to answer some of the questions that we are often asked about the course. Probably the most common question is "What do you do in your course?" The second most common must be "How can I teach a course like that?" I'll start with the first question:

What do you do in Guatemala and Belize?

The short answer to this question is a lot. I'll try to summarize.

Our approach to tropical ecology includes the standard elements you'd find in any ecology course: our students read a lot about the ecosystems and the prominent species of plants and animals they're likely to encounter. We teach them what we know about the systems we think we understand, and we tell them about the big gaps in our knowledge that we're aware of - knowing full well that we likely have blind spots we aren't aware of.

In Guatemala this means learning about the ecology of a dense forest growing on a karst plateau, and a deep lake where the water does not circulate much.

In Belize we study the mangroves and the barrier reef. The mangroves are like a porous filter between salt and fresh water, like a cell wall on a macro scale. They serve as a buffer against hurricanes; they keep topsoil from eroding into the sea, and they are a rich and colorful nursery for thousands of species.

The Importance of Human Ecology

We want our students to learn much more than the plants, animals, soil, air, and water, though. Perhaps more than anything, we want them to learn the human ecology of the places we visit. Ecology is not merely an academic study; it is, at its heart, the study of both the world and of our place in it. We don't just look at macaws, jaguars, vines, and ceiba trees; we look at the way our lives - even our visit to these amazing places - affect and are affected by these plants and animals. We don't stay in hotels; we rent rooms in local homes, and we eat meals with local people. We hire local teachers to teach us Spanish and the Itzá language. We study the history of the Itzá people, and we visit ancient ruins. We walk through the forest and camp overnight with local guides who can teach us what they know of that place. We spend time playing soccer with a local youth group, we talk with and listen to local teachers, nurses, physicians, forest rangers, ecologists, NGO volunteers, government officials, town elders, and children. If the ecology of the place matters, surely it matters because these people whose ancestors have lived there for so long matter.

In fact, even if you think they don't matter to you, if you're reading this post in North America these people do matter to you. If their ecology suffers, they will be forced to move to look for new sources of income and food. Simple-minded and disingenuous politicians will tell you this is a problem to be solved by erecting a wall on our border, but walls are a partial solution at best, and at worst, they are blinders that keep us from seeing the source of the problem; walls ignore the real illness and conceal the symptoms, as though willful ignorance were good medicine. The real question - in my mind, anyway - is why anyone who lived on the shores of Lake Petén Itzá would ever want to leave. The answer is that people leave beautiful homes when those homes cease to be liveable. Which means the medicine that is needed is one that treats the illness itself, and not just the symptoms. My students (I hope) return from our course no longer able to see Guatemalan immigrants to the United States as a mere abstraction. Break bread in someone's home and you will see that they are human, too, with lives as particular and intricate and important and rooted as your own. Only when we disturb those roots and strip away the soil must the lives be transplanted.

This is what I mean by human ecology.

Where do you go?

Our time in Guatemala is chiefly in central and northern Petén. Until recently, the landscape of northern Petén was dominated by dense forest, mostly old-growth lowland forests. Surface water is mostly wetlands that vary considerably from one season to the next. There are several small-to-medium-sized rivers, and small streams, but I think a good deal of the water flows underground in karst formations; the Petén has thin soil over a wide karst plateau. There is not much water flowing on the surface. In the center of Petén there is one very deep lake, Lake Petén Itzá. This is a gem in the forest. Flying over it on a sunny day you can see the shallows fade from pale green to rich emerald, and the depths along the north side of the lake plunge to amethyst and dark sapphire. The lake has no obvious inflow or outflow, except a few small streams flowing in from the south and west, and a little creek flowing out in the east.

In Belize we spend most of our time on one of the barrier islands that have no permanent residents. We use that island as a home base from which we can boat out to patch reefs, mangroves, turtle grass beds, deep channels, and the fore-reef. We snorkel with our students in all these places, slowly gathering experiences of similar species in diverse environments, so that the students (and we) can see both the ecology of small places and the web of relations between those small places. In mangroves, for instance, we might see juvenile caribbean reef squid that are a few inches long. When we see them on patch reefs, they might be five or six inches long, and in deep water they might reach eight inches. Each location gives us a glimpse of another stage of their life cycle.

Why do you do this? Aren't you a Humanities professor?

Even if people don't often ask me this, it's obvious that quite a few people think it. Yes, I'm a professor of philosophy and classics, and I teach religion courses, too. But for my whole life I have been fascinated by life underwater. My most recent book was the result of eight years of researching the lives of brook trout in the Appalachian mountains, and much of my research now has to do with ocean and riparian environments in Alaska. I don't do much of what would count as research in the natural sciences, but I do spend a lot of time observing nature. This is both because I find it beautiful, and because I think it's a bad idea to try to formulate ethical principles about things I haven't experienced or seen firsthand. Of course it's not impossible to write policies about things one hasn't done; one needn't commit larceny before writing a law prohibiting theft. But experience teaches me things I might not learn in other ways, and that can keep me from trusting too much in my own opinions. As Aristotle put it,

How Can I Teach A Course Like This? Can others participate in this trip?

The answer to the second of these questions is both yes and no. When I'm in Guatemala and Belize, I'm teaching. Unfortunately, this means I don't have time to bring others along and act as their tour guide.

However, the people I work with in Guatemala - the Asociación Bio-Itzá - would be happy to have you come for a visit. They're in the small town of San Josè, Petèn, Guatemala, right on the north shores of the lake. And this is the answer to the first question. Want to teach such a course? Get in touch with Bio-Itzá and they can help you set it up.

You can get to San José by flying or driving to Flores, then going around the lake by bus or car to San José, about a twenty minute drive.

In San José they have a traditional community medicinal garden. Just north of town is the Bio-Itzá Reserve, where you can go for guided walking tours or overnight stays. It's rustic and gorgeous. (Visits to the Reserve must be arranged in advance through Bio-Itzá.)

When you stay in San José you can easily take a launch (a wooden motor boat) across the lake to Flores, the seat of Nojpetén or Tayasal, the last Maya kingdom that fell to the Spanish.

Flores is a pretty place as well, and I like to take my students to visit ARCAS to see their animal rehabilitation center. (There's a great documentary about that place that was on PBS this year called "Jungle Animal Hospital.")

If you stay in San José, you can also take a short trip (about a half hour by car) to Tikal, or to Yaxhá, both of which are amazingly well-preserved Maya ruins. A little further past Tikal is Uaxactún, where you can see more ruins, and you can also visit a community that is trying to practice sustainable forestry.

This region is not like the tourist areas of Western Guatemala; it's more like the rural frontier of Guatemala, a long-neglected place that is now at risk of being overrun by slash-and-burn forestry, cattle farms, and oil development. It makes me think of the Dakotas over the last century; the population is small and indigenous, and most people in power in Guatemala seem to consider the forest to be a wasteland that is better burned down than preserved. I do not share that view, and while I know that more tourism will bring development and other risks to both culture and forest, the risks are already there in other forms. I hope that ecotourism will offer some counterweight to the other kinds of development that don't seek to preserve the biological integrity or cultural history of this place.

|

| Sunrise on the Barrier Reef in Belize |

In this post I'll try to answer some of the questions that we are often asked about the course. Probably the most common question is "What do you do in your course?" The second most common must be "How can I teach a course like that?" I'll start with the first question:

What do you do in Guatemala and Belize?

The short answer to this question is a lot. I'll try to summarize.

Our approach to tropical ecology includes the standard elements you'd find in any ecology course: our students read a lot about the ecosystems and the prominent species of plants and animals they're likely to encounter. We teach them what we know about the systems we think we understand, and we tell them about the big gaps in our knowledge that we're aware of - knowing full well that we likely have blind spots we aren't aware of.

In Guatemala this means learning about the ecology of a dense forest growing on a karst plateau, and a deep lake where the water does not circulate much.

In Belize we study the mangroves and the barrier reef. The mangroves are like a porous filter between salt and fresh water, like a cell wall on a macro scale. They serve as a buffer against hurricanes; they keep topsoil from eroding into the sea, and they are a rich and colorful nursery for thousands of species.

The Importance of Human Ecology

We want our students to learn much more than the plants, animals, soil, air, and water, though. Perhaps more than anything, we want them to learn the human ecology of the places we visit. Ecology is not merely an academic study; it is, at its heart, the study of both the world and of our place in it. We don't just look at macaws, jaguars, vines, and ceiba trees; we look at the way our lives - even our visit to these amazing places - affect and are affected by these plants and animals. We don't stay in hotels; we rent rooms in local homes, and we eat meals with local people. We hire local teachers to teach us Spanish and the Itzá language. We study the history of the Itzá people, and we visit ancient ruins. We walk through the forest and camp overnight with local guides who can teach us what they know of that place. We spend time playing soccer with a local youth group, we talk with and listen to local teachers, nurses, physicians, forest rangers, ecologists, NGO volunteers, government officials, town elders, and children. If the ecology of the place matters, surely it matters because these people whose ancestors have lived there for so long matter.

|

| Tikal |

|

| The church in San José, Petén, Guatemala |

In fact, even if you think they don't matter to you, if you're reading this post in North America these people do matter to you. If their ecology suffers, they will be forced to move to look for new sources of income and food. Simple-minded and disingenuous politicians will tell you this is a problem to be solved by erecting a wall on our border, but walls are a partial solution at best, and at worst, they are blinders that keep us from seeing the source of the problem; walls ignore the real illness and conceal the symptoms, as though willful ignorance were good medicine. The real question - in my mind, anyway - is why anyone who lived on the shores of Lake Petén Itzá would ever want to leave. The answer is that people leave beautiful homes when those homes cease to be liveable. Which means the medicine that is needed is one that treats the illness itself, and not just the symptoms. My students (I hope) return from our course no longer able to see Guatemalan immigrants to the United States as a mere abstraction. Break bread in someone's home and you will see that they are human, too, with lives as particular and intricate and important and rooted as your own. Only when we disturb those roots and strip away the soil must the lives be transplanted.

This is what I mean by human ecology.

|

| One of my students examining and being examined by nature |

Where do you go?

Our time in Guatemala is chiefly in central and northern Petén. Until recently, the landscape of northern Petén was dominated by dense forest, mostly old-growth lowland forests. Surface water is mostly wetlands that vary considerably from one season to the next. There are several small-to-medium-sized rivers, and small streams, but I think a good deal of the water flows underground in karst formations; the Petén has thin soil over a wide karst plateau. There is not much water flowing on the surface. In the center of Petén there is one very deep lake, Lake Petén Itzá. This is a gem in the forest. Flying over it on a sunny day you can see the shallows fade from pale green to rich emerald, and the depths along the north side of the lake plunge to amethyst and dark sapphire. The lake has no obvious inflow or outflow, except a few small streams flowing in from the south and west, and a little creek flowing out in the east.

|

| My students leap into Lake Petén Itzá to cool off. |

In Belize we spend most of our time on one of the barrier islands that have no permanent residents. We use that island as a home base from which we can boat out to patch reefs, mangroves, turtle grass beds, deep channels, and the fore-reef. We snorkel with our students in all these places, slowly gathering experiences of similar species in diverse environments, so that the students (and we) can see both the ecology of small places and the web of relations between those small places. In mangroves, for instance, we might see juvenile caribbean reef squid that are a few inches long. When we see them on patch reefs, they might be five or six inches long, and in deep water they might reach eight inches. Each location gives us a glimpse of another stage of their life cycle.

|

| My students watch the sunset in Belize |

Why do you do this? Aren't you a Humanities professor?

Even if people don't often ask me this, it's obvious that quite a few people think it. Yes, I'm a professor of philosophy and classics, and I teach religion courses, too. But for my whole life I have been fascinated by life underwater. My most recent book was the result of eight years of researching the lives of brook trout in the Appalachian mountains, and much of my research now has to do with ocean and riparian environments in Alaska. I don't do much of what would count as research in the natural sciences, but I do spend a lot of time observing nature. This is both because I find it beautiful, and because I think it's a bad idea to try to formulate ethical principles about things I haven't experienced or seen firsthand. Of course it's not impossible to write policies about things one hasn't done; one needn't commit larceny before writing a law prohibiting theft. But experience teaches me things I might not learn in other ways, and that can keep me from trusting too much in my own opinions. As Aristotle put it,

“Lack of experience diminishes our power of taking a comprehensive view of the admitted facts. Hence those who dwell in intimate association with nature and its phenomena grow more and more able to formulate, as the foundations of their theories, principles such as to admit of a wide and coherent development: while those whom devotion to abstract discussions has rendered unobservant of the facts are too ready to dogmatize on the basis of a few observations.” Aristotle, De Generatione et corruptione, 316a5-10 (Basic Works, McKeon, trans.)I want to "dwell in intimate association of nature and its phenomena," and being able to formulate better principles is a nice side effect of doing so.

How Can I Teach A Course Like This? Can others participate in this trip?

The answer to the second of these questions is both yes and no. When I'm in Guatemala and Belize, I'm teaching. Unfortunately, this means I don't have time to bring others along and act as their tour guide.

However, the people I work with in Guatemala - the Asociación Bio-Itzá - would be happy to have you come for a visit. They're in the small town of San Josè, Petèn, Guatemala, right on the north shores of the lake. And this is the answer to the first question. Want to teach such a course? Get in touch with Bio-Itzá and they can help you set it up.

You can get to San José by flying or driving to Flores, then going around the lake by bus or car to San José, about a twenty minute drive.

|

| Flores, Petén, Guatemala |

In San José they have a traditional community medicinal garden. Just north of town is the Bio-Itzá Reserve, where you can go for guided walking tours or overnight stays. It's rustic and gorgeous. (Visits to the Reserve must be arranged in advance through Bio-Itzá.)

When you stay in San José you can easily take a launch (a wooden motor boat) across the lake to Flores, the seat of Nojpetén or Tayasal, the last Maya kingdom that fell to the Spanish.

Flores is a pretty place as well, and I like to take my students to visit ARCAS to see their animal rehabilitation center. (There's a great documentary about that place that was on PBS this year called "Jungle Animal Hospital.")

|

| Scarlet macaws being rehabilitated at ARCAS so they can be released back into the wild |

If you stay in San José, you can also take a short trip (about a half hour by car) to Tikal, or to Yaxhá, both of which are amazingly well-preserved Maya ruins. A little further past Tikal is Uaxactún, where you can see more ruins, and you can also visit a community that is trying to practice sustainable forestry.

This region is not like the tourist areas of Western Guatemala; it's more like the rural frontier of Guatemala, a long-neglected place that is now at risk of being overrun by slash-and-burn forestry, cattle farms, and oil development. It makes me think of the Dakotas over the last century; the population is small and indigenous, and most people in power in Guatemala seem to consider the forest to be a wasteland that is better burned down than preserved. I do not share that view, and while I know that more tourism will bring development and other risks to both culture and forest, the risks are already there in other forms. I hope that ecotourism will offer some counterweight to the other kinds of development that don't seek to preserve the biological integrity or cultural history of this place.

∞

Butterflies In My Stomach

This

week I’ve been helping a student with a lepidoptera project. The project is hers, and she's not in one of my classes, though she did take the Tropical Ecology class I teach in Central America this year.

Here is the danger of becoming a professor of Environmental Humanities: people begin to assume that you care about nature, and that you are willing to share what you know.

Both of these things are true, by the way. (Many of my photos of wildlife and nature are here, on my Instagram account. I do care, and I am delighted to share the little I know.)

Over the years, I have come to love insects. This has come about partly through my years studying trout, char, and salmon, and of the places they live. I've spent a good portion of the last decade walking Appalachian waterways from Maine to Georgia. Over that same time, I've walked hundreds of miles through the remaining forests of northern Guatemala and Nicaragua. As both a researcher and teacher I've walked through the mountains of the American West; and I've made similar excursions to the foothills of the Brooks Range, the Kenai Peninsula, and Lake Clark National Park in Alaska.

The fish that I love depend upon the insects, so, like so many people who gaze at salmonids, I have come to know many riparian insects.

Once you study the insects along the streams, you start to notice the other plants and animals that depend upon them, too. In Kentucky I have come upon a steaming pile of bear scat that was full of half-digested cicadas. I've started to notice the wings of insects, left behind by the birds that only eat the fleshy bodies of the bugs they catch.

From there, it's not a big leap to realize that if the fish and the birds and the plants need the insects, then so do I. Butterflies and other insects feed the larger animals my species eats, and they pollinate the plants that feed us. All of us have the actions of butterflies in our stomachs. Can you see the lepidoptera in this next photo? There are quite a few of them, resting on the bark of this tree in Petén.

Little six-legged creatures feed us all. The small things matter.

And so do my students, even if they're not currently enrolled in one of my classes.

So in the past week I’ve gathered a few hundred of my best butterfly photos to share with my student. This photo is one of the worst in photo quality, but it’s a great image nevertheless:

I took this nine years ago in the mountains in Kentucky while working on my book on brook trout. Three distinct species of butterflies are gathered here, sipping minerals from the ground. My coauthor Matthew Dickerson and I came upon this arboreal banquet by chance.

I wish I'd had a better camera with me. For now, the blurry image is enough to bring to mind that memory of hundreds of lepidoptera sipping and supping together on the forest floor, filling their bellies with the bare earth before flying off to pollinate flowers that, through a complex net of relationships, would someday fill my belly too.

|

| Kentucky roadside butterfly banquet. Can you see the little one? |

Here is the danger of becoming a professor of Environmental Humanities: people begin to assume that you care about nature, and that you are willing to share what you know.

Both of these things are true, by the way. (Many of my photos of wildlife and nature are here, on my Instagram account. I do care, and I am delighted to share the little I know.)

*****

Over the years, I have come to love insects. This has come about partly through my years studying trout, char, and salmon, and of the places they live. I've spent a good portion of the last decade walking Appalachian waterways from Maine to Georgia. Over that same time, I've walked hundreds of miles through the remaining forests of northern Guatemala and Nicaragua. As both a researcher and teacher I've walked through the mountains of the American West; and I've made similar excursions to the foothills of the Brooks Range, the Kenai Peninsula, and Lake Clark National Park in Alaska.

The fish that I love depend upon the insects, so, like so many people who gaze at salmonids, I have come to know many riparian insects.

Once you study the insects along the streams, you start to notice the other plants and animals that depend upon them, too. In Kentucky I have come upon a steaming pile of bear scat that was full of half-digested cicadas. I've started to notice the wings of insects, left behind by the birds that only eat the fleshy bodies of the bugs they catch.

|

| Butterfly wing, left behind by birds. Guatemala. |

From there, it's not a big leap to realize that if the fish and the birds and the plants need the insects, then so do I. Butterflies and other insects feed the larger animals my species eats, and they pollinate the plants that feed us. All of us have the actions of butterflies in our stomachs. Can you see the lepidoptera in this next photo? There are quite a few of them, resting on the bark of this tree in Petén.

|

| Gray cracker butterflies, Petén, Guatemala. |

Little six-legged creatures feed us all. The small things matter.

And so do my students, even if they're not currently enrolled in one of my classes.

So in the past week I’ve gathered a few hundred of my best butterfly photos to share with my student. This photo is one of the worst in photo quality, but it’s a great image nevertheless:

|

| Butterflies on the ground in Kentucky, 2008. |

I took this nine years ago in the mountains in Kentucky while working on my book on brook trout. Three distinct species of butterflies are gathered here, sipping minerals from the ground. My coauthor Matthew Dickerson and I came upon this arboreal banquet by chance.

I wish I'd had a better camera with me. For now, the blurry image is enough to bring to mind that memory of hundreds of lepidoptera sipping and supping together on the forest floor, filling their bellies with the bare earth before flying off to pollinate flowers that, through a complex net of relationships, would someday fill my belly too.

∞

2) Second, fill your toolbox—and your community’s toolbox—with bear poop. This is an inside reference my students will understand by the end of the semester, but I'll fill you in briefly: I take the time when I am in the wild to look at animal scat, because it is often a picture of what food is available to the animals, and that, in turn, is a picture of the problems the environment is facing. Paying attention to scat over time gives you a long-term picture of changes to the environment. Poop is a tool that is free, that is right in front of you, and that is easy to overlook as unimportant or distasteful. Bear poop that is full of salmon bones tells me one story; bear poop that is full of berries tells me another. I don't literally fill my toolbox with bear poop, but paying attention to negligible things like bear poop gives me new tools I wouldn't have otherwise. What does this mean for us?

Wicked Problems in Environmental Policy

When I first started teaching environmental philosophy courses I used anthologies of helpful articles for my core readings. These included articles about topics ranging from environmental ethics and philosophy of nature to animal rights, land ethics, and pollution.

The more I read, the more I realized how hard it is to do more than a simple survey of problems in a single semester. From early on, I started adding narratives to my classes, using texts by people like Wendell Berry, Aldo Leopold, Rachel Carson, Henry Thoreau, Kathleen Dean Moore, and Vandana Shiva. I've also included sacred texts and poems from around the world, because while many of those narratives and poems don't solve the problems, the form of writing they use makes them a flowing spring of renewable thought-provocation.

Recently I've taken on an even broader approach to teaching environmental humanities courses by designing a course I call "How To Begin To Solve 'Wicked Problems' In Environmental Policy."

I won't explain everything here, because the topic is too big to explain in detail now, but I will try to explain what I mean by the title of the course.

The previous sentence is a picture of what the course is like: there's too much to cover all at once; there are too many elements to explain to do them all justice in a short space; so it's often more helpful to begin the process and to keep it before you as an ongoing matter than to treat it as a simple problem to be solved with a simple solution.

This is the nature of "wicked problems," after all. It's not that the problems are wicked or evil, but they are immensely complex, with many changeable parts or situations, and any solution that is offered will change the situation. An example might help to illustrate what I mean. Let's consider world poverty.

If we take poverty to mean simply the lack of funds on the part of the impoverished, then it is a simple problem to solve (even if it isn't an easy one.) All you have to do is find out how much money the poor lack, and give it to them. If poverty were simply a lack of funds, then filling that lack with funds would be the solution. But this solution fails to ask what caused the lack of funds in the first place, or why it matters. And it fails to acknowledge that handing over money changes the situation into which the money is given. Economists know that economic predictions are not a precise science. There are simply too many factors at play in human economic systems. As the 17th-century philosopher Mary Astell put it, "single medicines are too weak to cure such complicated distempers." [1] Some medicines have side effects, after all, and the same is true in economics, and in many other disciplines.

So how do I teach this course? I start with some problems I understand too poorly and some narratives that I know will be incomplete, focusing on two places where I teach and do research: Guatemala's Petén Department, and the headwaters of the Bristol Bay region of Alaska. In both cases, there is competition for certain resources, and the use of one resource can threaten or permanently impair other resources.

I don't expect my students can solve these problems for other people, but they are problems I've come to know more and more intimately over years of firsthand experience of the regions in question. So I tell my students stories about those places, and I try to introduce them (often by video calls) to people who work in those places. I want my students to get to know as many different stakeholders as possible, and to hear their stories in the context of those peoples' lives.

You might justifiably ask: if I don't expect my students to solve the problems, and if I myself don't have the solutions, what justifies teaching such a course? My answer is, first, that it is better to try than not to try, and second, that in looking at problems in which we don't feel a personal investment we can often learn to tackle the problems that are closer to home.

There's an ethical and political upside to this, too: once you see that certain problems are "wicked problems," you can start to see the ways that policy-touting charlatans try to pull the wool over your eyes. It is a very old political trick to win votes by claiming that wicked problems are simple ones, and that only you or your party can see the simple solution. This gives a strange comfort to voters who have been perplexed by complexity, and that comfort wins votes on the cheap, at the expense of humility, neighborly care, mutual struggle, bipartisan collaboration, and seriousness of thought.

I have more to say about this - some of it no doubt will be mistaken - but for now I'll wrap up this piece with a rough outline of what I propose to my students as a way to begin to solve wicked problems in environmental policy. Here it is:

1) First, identify the community of stakeholders.

a. Do so for their perspectives, for their interests, and for their tools.

b. Ask: Who are the stakeholders?

i. Go beyond the financial stakeholders or stockholders.

ii. Include everyone who affects, or is affected by, the policy under consideration.

c. Remember Charles Peirce’s idea: science is the work of a community, not of an individual.

d. Make concept maps, and use other kinds of visualizations of the problems.

i. This is a way of utilizing a broad range of tools. Don’t just use the tools others tell you are relevant; include the arts and the sciences alike.

ii. Drawing and sketching pictures will help you to see better. As Louis Agassiz said, “the pencil is one of the best eyes.” It is often better than a camera.

iii. Music, literature, poetry, and the visual arts may be just as helpful as the tools offered by STEM fields and policy-making professions like law.

iv. If you include the arts, you wind up including the artists; similarly, if you exclude the arts, you exclude the wisdom and insight of the artists.

v. Include ordinary daily practices. Learn to fish, even if you don’t plan to fish. Hike in the woods, even if you don’t like the outdoors. These are, in a way, practices of paying attention to the world.

e. Include other voices and texts in the conversation, not just the shareholders, but all the stakeholders.

f. Define “stakeholders” as broadly as you can. Include a community across generations. Include the departed and the not-yet-born if possible.

i. Traditions might be full of wisdom, so don’t ignore them, especially if they are specific to a place. Traditions may be inarticulate wisdom that is tested by time.

ii. Plan for seven generations. I sometimes think of this as the difference between planting those crops you will harvest this year and planting hardwood trees so that they will be old-growth trees long after you are dead. Humans – and other species – need both kinds of plants.

a. Do so for their perspectives, for their interests, and for their tools.

b. Ask: Who are the stakeholders?

i. Go beyond the financial stakeholders or stockholders.

ii. Include everyone who affects, or is affected by, the policy under consideration.

c. Remember Charles Peirce’s idea: science is the work of a community, not of an individual.

d. Make concept maps, and use other kinds of visualizations of the problems.

i. This is a way of utilizing a broad range of tools. Don’t just use the tools others tell you are relevant; include the arts and the sciences alike.

ii. Drawing and sketching pictures will help you to see better. As Louis Agassiz said, “the pencil is one of the best eyes.” It is often better than a camera.

iii. Music, literature, poetry, and the visual arts may be just as helpful as the tools offered by STEM fields and policy-making professions like law.

iv. If you include the arts, you wind up including the artists; similarly, if you exclude the arts, you exclude the wisdom and insight of the artists.

v. Include ordinary daily practices. Learn to fish, even if you don’t plan to fish. Hike in the woods, even if you don’t like the outdoors. These are, in a way, practices of paying attention to the world.

e. Include other voices and texts in the conversation, not just the shareholders, but all the stakeholders.

f. Define “stakeholders” as broadly as you can. Include a community across generations. Include the departed and the not-yet-born if possible.

i. Traditions might be full of wisdom, so don’t ignore them, especially if they are specific to a place. Traditions may be inarticulate wisdom that is tested by time.

ii. Plan for seven generations. I sometimes think of this as the difference between planting those crops you will harvest this year and planting hardwood trees so that they will be old-growth trees long after you are dead. Humans – and other species – need both kinds of plants.

|

| Bear scat along a salmon river, Katmai Preserve, Alaska |

2) Second, fill your toolbox—and your community’s toolbox—with bear poop. This is an inside reference my students will understand by the end of the semester, but I'll fill you in briefly: I take the time when I am in the wild to look at animal scat, because it is often a picture of what food is available to the animals, and that, in turn, is a picture of the problems the environment is facing. Paying attention to scat over time gives you a long-term picture of changes to the environment. Poop is a tool that is free, that is right in front of you, and that is easy to overlook as unimportant or distasteful. Bear poop that is full of salmon bones tells me one story; bear poop that is full of berries tells me another. I don't literally fill my toolbox with bear poop, but paying attention to negligible things like bear poop gives me new tools I wouldn't have otherwise. What does this mean for us?

a. Identify the community’s tools, perspectives, and skills, and seek to integrate them into a tool-wielding community.

b. See the problem as broadly as you can. We tend to frame problems based on our perspective, so do what you can to gain the perspectives of others.

Emerson: move your body so that your eyes see the world from a different angle.

c. Try to gain as many tools as you can

d. Value experience and first-hand knowledge

i. Go underwater – that is, look at the world in new and unfamiliar ways, from unfamiliar vantage points.

ii. Travel – get to know the world differently, and get to know how others know the world. Don't just do tourism, but saunter, as Thoreau puts it.

iii. Learn the languages you can – even a little bit will make a difference. Words are tools, and they are lenses through which to see the world anew.

iv. Study “unnecessary” knowledge, and not just the knowledge others tell you is necessary – don’t let others tell you what tools are worth gaining.

v. Foster your curiosity. Don’t let it die of neglect.

e. Engage in labs, even in the Humanities – learn experientially.

3) Third, have what Peirce calls “regulative ideals”

3) Third, have what Peirce calls “regulative ideals”

a. Aim high, and have a direction. But

b. Recognize that the direction will change; this is like taking bearings while navigating. You have to keep adjusting as you move and as you discover the landscape

4) Fourth, don’t expect perfection

4) Fourth, don’t expect perfection

a. and don’t expect ultimate solutions. Expect that truly ‘wicked’ problems will continue to be problems, and that they will continue to change and to spawn new problems. Such is life.

b. Instead, expect meliorism, growth, improvement

c. Peirce uses some odd words to describe all this: tychism, synechism, agapism: chance, continuity, love. Someday, look these up, or ask me to define them for you. Vocabulary is a powerful tool.

5) Fifth, do expect growth, and strive to cultivate good things. This is the work of ethics.

6) Sixth, do expect to be part of a community that continues to work on the problems for a long time.

7) And seventh, don’t give up!

5) Fifth, do expect growth, and strive to cultivate good things. This is the work of ethics.

6) Sixth, do expect to be part of a community that continues to work on the problems for a long time.

7) And seventh, don’t give up!

Of course it is possible to solve environmental policy problems apart from a community; once you’re no longer a part of a community, “policy” takes on a simpler meaning, and so does “environmental.” But merely redefining words—or merely divorcing yourself from a situation—doesn’t solve the problem. Rather, those decisions only blind us to the problem. This is satisfying our own irritation rather than satisfying the needs generated by the actual problem.

*****

[1] Mary Astell, A Serious Proposal to the Ladies, Sharon L. Jansen, ed. (Steilacoom, WA: Saltar's Point Press, 2014) p.65.

∞

The Trace I Left Behind

This summer I spent several weeks in and around Lake Clark National Park doing research on trout, salmon, and char.

Sometimes I get quizzical looks when I say that I, a philosophy and classics professor, am researching fish. Let me explain.

I teach environmental philosophy and a range of classes in what I call "environmental humanities." These include courses in environmental ethics, nature writing, philosophy of nature, and even a course on environmental law and policy for first-year undergraduates, as an introduction to being a university student.

I also teach courses in field ecology, including a monthlong course in tropical ecology in Guatemala and Belize. I teach in Greece over my spring break, and this year we will be looking at the expansion of fish farms in the Mediterranean and how fishing has changed there over the last six thousand years.

Closer to home, I teach and practice what Norwegians call friluftsliv, or life in the free air. Whenever possible, I teach outdoors. Most years, I take my ancient philosophy students camping in the Badlands National Park to watch the Orionid meteor shower while we lie on sleeping bags under the stars.

In all of this, my aim is to make sure that nature is not an abstraction to my students, nor to me. I want to know the places the fish live, the grasslands the bison roam, the forests where the jaguar and the ocelot hunt, the tundra rivers where the Dolly Varden chase the salmon under the watchful gaze of the bears.

In other words, my aim is to stay in contact with wildness, and to do so in a way that allows me to take something valuable home: intimate knowledge. I am not a scientist, so I don't bring samples back to a laboratory. I do bring home photographs, and I do spend a lot of time making observations of the places I work, so that I can bring home notebooks full of writing to share with my students. And of course, I write books and articles to share with others.

This summer, I was sorely tempted to bring something else home from Lake Clark: a tiny fossil. I had chartered a float plane to take me to a fairly remote lake, and there my fellow researchers and I walked the shore to the mouth of a stream full of spawning salmon and rainbow trout.

As I often do, I sat down on the gravel and started to turn over rocks to see what invertebrates were living there. The salmon are bright red and eye-catching, but the bugs and spiders tell an important part of the story of a place, as Kurt Fausch has written about in his recent book, For The Love Of Rivers. Who was it - J.B.S. Haldane, perhaps? - who quipped that God has "an inordinate fondness for beetles." The world is full of wonderful, tiny lives that are easy to overlook.

I don't try to bring beetles home, but one insect tempted me this summer. Really, it was just a trace of an insect, just the trace of its wings, in fact. I can't even tell you what insect it was. All I can tell you is that somewhere near that river, probably millions of years ago, something like a dragonfly died in the mud, and the river graced its delicate wings with the cerement of silt. That silt took the form of the wings, those wings left a fingerprint - a wingprint - on the earth. And this summer, I found that print, that delicate, wonderful trace.

While my son and my friend and our pilot walked, I sat with that stone in my hand and thought about pocketing it. Here I was in the wilderness, and no one would know. It's one tiny stone in the largest state in the union; who would miss it?

Ah, but it is one tiny stone that does not belong to me. It is one tiny stone in a vast wilderness that belongs to all of us, and to all who will come after us. It is one tiny piece of rock with an incomplete fossil of a little odonata. The river there has held it and cared for it since time immemorial.

Now I am back in South Dakota, but a tiny trace of my heart remains along the strand of that stream in Alaska. It lies there, wrapped around that delicate trace of insect wing, and I will never find it again in that vast wilderness.

But perhaps someone else will. Until then, perhaps it is best not to let Midas' longings turn our hearts to stone too soon. Let's walk the shores together, I will continue to say to my students. And let's bring something intangible home in our memories. And let's do the hard work of leaving behind the beautiful, delicate traces that wildness has safeguarded for so many, many years.

Sometimes I get quizzical looks when I say that I, a philosophy and classics professor, am researching fish. Let me explain.

I teach environmental philosophy and a range of classes in what I call "environmental humanities." These include courses in environmental ethics, nature writing, philosophy of nature, and even a course on environmental law and policy for first-year undergraduates, as an introduction to being a university student.

I also teach courses in field ecology, including a monthlong course in tropical ecology in Guatemala and Belize. I teach in Greece over my spring break, and this year we will be looking at the expansion of fish farms in the Mediterranean and how fishing has changed there over the last six thousand years.

Closer to home, I teach and practice what Norwegians call friluftsliv, or life in the free air. Whenever possible, I teach outdoors. Most years, I take my ancient philosophy students camping in the Badlands National Park to watch the Orionid meteor shower while we lie on sleeping bags under the stars.

In all of this, my aim is to make sure that nature is not an abstraction to my students, nor to me. I want to know the places the fish live, the grasslands the bison roam, the forests where the jaguar and the ocelot hunt, the tundra rivers where the Dolly Varden chase the salmon under the watchful gaze of the bears.

In other words, my aim is to stay in contact with wildness, and to do so in a way that allows me to take something valuable home: intimate knowledge. I am not a scientist, so I don't bring samples back to a laboratory. I do bring home photographs, and I do spend a lot of time making observations of the places I work, so that I can bring home notebooks full of writing to share with my students. And of course, I write books and articles to share with others.

This summer, I was sorely tempted to bring something else home from Lake Clark: a tiny fossil. I had chartered a float plane to take me to a fairly remote lake, and there my fellow researchers and I walked the shore to the mouth of a stream full of spawning salmon and rainbow trout.

|

| Salmon preparing to spawn |

As I often do, I sat down on the gravel and started to turn over rocks to see what invertebrates were living there. The salmon are bright red and eye-catching, but the bugs and spiders tell an important part of the story of a place, as Kurt Fausch has written about in his recent book, For The Love Of Rivers. Who was it - J.B.S. Haldane, perhaps? - who quipped that God has "an inordinate fondness for beetles." The world is full of wonderful, tiny lives that are easy to overlook.

I don't try to bring beetles home, but one insect tempted me this summer. Really, it was just a trace of an insect, just the trace of its wings, in fact. I can't even tell you what insect it was. All I can tell you is that somewhere near that river, probably millions of years ago, something like a dragonfly died in the mud, and the river graced its delicate wings with the cerement of silt. That silt took the form of the wings, those wings left a fingerprint - a wingprint - on the earth. And this summer, I found that print, that delicate, wonderful trace.

|

| Fossilized trace of an insect's wing |

While my son and my friend and our pilot walked, I sat with that stone in my hand and thought about pocketing it. Here I was in the wilderness, and no one would know. It's one tiny stone in the largest state in the union; who would miss it?

Ah, but it is one tiny stone that does not belong to me. It is one tiny stone in a vast wilderness that belongs to all of us, and to all who will come after us. It is one tiny piece of rock with an incomplete fossil of a little odonata. The river there has held it and cared for it since time immemorial.

Now I am back in South Dakota, but a tiny trace of my heart remains along the strand of that stream in Alaska. It lies there, wrapped around that delicate trace of insect wing, and I will never find it again in that vast wilderness.

But perhaps someone else will. Until then, perhaps it is best not to let Midas' longings turn our hearts to stone too soon. Let's walk the shores together, I will continue to say to my students. And let's bring something intangible home in our memories. And let's do the hard work of leaving behind the beautiful, delicate traces that wildness has safeguarded for so many, many years.

∞

A Pretty Good Year

Last year was a pretty good year. Or at least, what I remember of it was pretty good.

As my regular readers know, I'm a professor of philosophy and classics, and I teach a wide range of classes. (You can click on the "Teaching" link above to see a sampling of the courses I teach.)

Often people assume that means I wear tweed and a bowtie and that I spend my time in classrooms talking about old books. All that is true, but it's only a part of what I do.

In fact, most of my favorite classrooms are outdoors, where I'm likely to be found wearing jeans and hiking boots, a parka, or a wetsuit and snorkel.

Over the last dozen years or so my teaching and research have tended towards the environmental humanities. Think of this as the merging of the humanities side of the liberal arts with a close observation of the natural world. I consider my work to be a continuation of the work that Thales and Aristotle did when they paid close attention to animals on the ground and to the skies above, and of the work of Peirce, Thoreau, and Bugbee, all of whom let a rising trout or a solar eclipse provoke philosophical reflection.

While I don't work in an indoor laboratory, I think that education is not about the imparting of information or the filling of an empty vessel with ideas. Education is the kindling of a fire, as Plutarch wrote. And that fire is kindled by the kinds of experiences that we get in labs, art studios, shared meals, liturgies, study travel, and seminars. Lecture halls are a fine place to discuss environmental policy, to be sure. But so is a prairie, especially when you're waiting for water to boil on your camp stove, and watching the sun's beams break over the horizon and melt a light frost on your tent.

When I'm at home, I like to take my classes outside to sit under trees on campus. In the fall, I try to bring my Ancient Philosophy students camping in the Badlands of South Dakota where we can view the stars far from urban glow. Most Januaries, my students and I are in the subtropical forests of Guatemala and on a barrier island in Belize, studying ecology and culture. I rarely take a spring break, since I usually take that week to teach a course in Greece. Last summer I started teaching a class on trout and salmon in Alaska.

Those are all beautiful, memorable places, but I don't visit them as a tourist. I go to these places because I want my students to understand what is at stake when we talk about environmental regulations and practices. I want them to meet displaced people whose permafrost islands are melting or whose forests are being burned down for meager cropland. I want them to see the disappearing mangroves so that they can consider the full cost of seafood. When they stay in homes in Guatemala, my students will meet people who can never again be a mere abstraction; after we return, my students will know that the people struggling to cross borders are not nameless, faceless strangers, but people who are looking for ways to feed those they love.

A little less than a year ago I was finishing up a year that had brought me to all these places. I taught in the South Dakota Badlands, in Central America, in Greece, and in Alaska. Along the way, I had begun studying environmental law at Vermont Law School as a way of enhancing my teaching and my research. It was a good year, and as August was winding down, my desk was covered with field notebooks full of observations from Alaska and Guatemala, ready to be written up. My field notes are usually accompanied by thousands of photographs, and hundreds of sketches. I began the fall semester last year ready to teach, and ready to write.

And then I wound up in the hospital with some serious injuries. Those injuries put a sudden stop to all my teaching last fall, and for a long time I lost most of my ability to write. (I'll try to write more about the injuries and my subsequent disabilities later; it's not an easy thing to write about yet.)

Now, as this summer hastens towards the beginning of another school year, I am able to look back on last year with a sense of good fortune - albeit mixed with one very bad day and its long-term consequences. Physically, I'm regaining my flexibility and strength, a little at a time. I'm not where I was a year ago, and I may never be there again, but I'm alive and able to walk, so I'll count that in the "win" column of my life's scorecard. Intellectually, most people seem to think I'm doing fine, so I'll also count that as a win. Although it left me exhausted each day, I was able to teach again this spring, and I plan to be back in my classrooms (Deo volente!) this fall.

But here are these field notebooks, and hundreds of unedited pages on my hard drive. It was my habit to write daily. Over the last year, recovering from a brain injury has made it hard to write more than a few sentences at a time.

This morning I was looking at some of my pictures from my research in the Arctic last summer, and I was hit with a feeling of loss. Those photos and those notes should be a book by now, and perhaps several articles and book chapters, too. Instead, over the last year, as I have waited for my body and brain to heal, and as I struggled to do my teaching, I had no strength to write.

It feels funny to say that, but perhaps I am not alone in finding that a brain injury can be slow to heal and extremely tiring. I don't say that to get your sympathy. I am blessed with a very supportive community and an amazing wife who somehow has kept our life together and nursed me through my healing process. I'm fortunate. But if you've read this far, you might consider whether there are others around you who look like they're doing well physically but who might be nursing invisible wounds or who might be struggling to cope with invisible disabilities. This past year has given me a new perspective on that by making me aware of my own disabilities, most of which you won't notice if you see me at the gym or in one of my classrooms.

I might not be able to write another book yet, so for now, here's my plan: I'll write a little at a time. Thankfully, I've got my notes, sketches, and photos. I'll start with them.

If you're curious about how a professor of philosophy and classics does research and writing about nature - and how he works to recover from a serious brain injury - you might check out some of my recent publications. My book Downstream is the result of eight years of field research on the ecology of the Appalachians, with a focus on brook trout. On this blog you'll also find my recently published poem, "Sage Creek," which might give you a glimpse of my ancient philosophy class camping and stargazing in the Badlands. Or feel free to look at my photos on Instagram. Even when I can't teach in the field, I can still wander my garden with a hand lens and camera.

As my regular readers know, I'm a professor of philosophy and classics, and I teach a wide range of classes. (You can click on the "Teaching" link above to see a sampling of the courses I teach.)

Often people assume that means I wear tweed and a bowtie and that I spend my time in classrooms talking about old books. All that is true, but it's only a part of what I do.

In fact, most of my favorite classrooms are outdoors, where I'm likely to be found wearing jeans and hiking boots, a parka, or a wetsuit and snorkel.

Over the last dozen years or so my teaching and research have tended towards the environmental humanities. Think of this as the merging of the humanities side of the liberal arts with a close observation of the natural world. I consider my work to be a continuation of the work that Thales and Aristotle did when they paid close attention to animals on the ground and to the skies above, and of the work of Peirce, Thoreau, and Bugbee, all of whom let a rising trout or a solar eclipse provoke philosophical reflection.

While I don't work in an indoor laboratory, I think that education is not about the imparting of information or the filling of an empty vessel with ideas. Education is the kindling of a fire, as Plutarch wrote. And that fire is kindled by the kinds of experiences that we get in labs, art studios, shared meals, liturgies, study travel, and seminars. Lecture halls are a fine place to discuss environmental policy, to be sure. But so is a prairie, especially when you're waiting for water to boil on your camp stove, and watching the sun's beams break over the horizon and melt a light frost on your tent.

When I'm at home, I like to take my classes outside to sit under trees on campus. In the fall, I try to bring my Ancient Philosophy students camping in the Badlands of South Dakota where we can view the stars far from urban glow. Most Januaries, my students and I are in the subtropical forests of Guatemala and on a barrier island in Belize, studying ecology and culture. I rarely take a spring break, since I usually take that week to teach a course in Greece. Last summer I started teaching a class on trout and salmon in Alaska.

Those are all beautiful, memorable places, but I don't visit them as a tourist. I go to these places because I want my students to understand what is at stake when we talk about environmental regulations and practices. I want them to meet displaced people whose permafrost islands are melting or whose forests are being burned down for meager cropland. I want them to see the disappearing mangroves so that they can consider the full cost of seafood. When they stay in homes in Guatemala, my students will meet people who can never again be a mere abstraction; after we return, my students will know that the people struggling to cross borders are not nameless, faceless strangers, but people who are looking for ways to feed those they love.

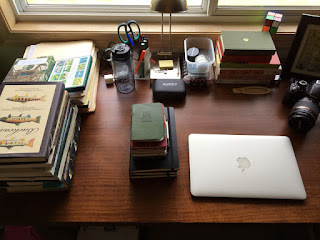

A little less than a year ago I was finishing up a year that had brought me to all these places. I taught in the South Dakota Badlands, in Central America, in Greece, and in Alaska. Along the way, I had begun studying environmental law at Vermont Law School as a way of enhancing my teaching and my research. It was a good year, and as August was winding down, my desk was covered with field notebooks full of observations from Alaska and Guatemala, ready to be written up. My field notes are usually accompanied by thousands of photographs, and hundreds of sketches. I began the fall semester last year ready to teach, and ready to write.

|

| Field notes. A picture of some of the work I do when I'm inside, and not teaching; or, if you like, a picture of my desk as I recover from my injuries. I have a lot of catching up to do. |

And then I wound up in the hospital with some serious injuries. Those injuries put a sudden stop to all my teaching last fall, and for a long time I lost most of my ability to write. (I'll try to write more about the injuries and my subsequent disabilities later; it's not an easy thing to write about yet.)

Now, as this summer hastens towards the beginning of another school year, I am able to look back on last year with a sense of good fortune - albeit mixed with one very bad day and its long-term consequences. Physically, I'm regaining my flexibility and strength, a little at a time. I'm not where I was a year ago, and I may never be there again, but I'm alive and able to walk, so I'll count that in the "win" column of my life's scorecard. Intellectually, most people seem to think I'm doing fine, so I'll also count that as a win. Although it left me exhausted each day, I was able to teach again this spring, and I plan to be back in my classrooms (Deo volente!) this fall.

But here are these field notebooks, and hundreds of unedited pages on my hard drive. It was my habit to write daily. Over the last year, recovering from a brain injury has made it hard to write more than a few sentences at a time.

This morning I was looking at some of my pictures from my research in the Arctic last summer, and I was hit with a feeling of loss. Those photos and those notes should be a book by now, and perhaps several articles and book chapters, too. Instead, over the last year, as I have waited for my body and brain to heal, and as I struggled to do my teaching, I had no strength to write.

It feels funny to say that, but perhaps I am not alone in finding that a brain injury can be slow to heal and extremely tiring. I don't say that to get your sympathy. I am blessed with a very supportive community and an amazing wife who somehow has kept our life together and nursed me through my healing process. I'm fortunate. But if you've read this far, you might consider whether there are others around you who look like they're doing well physically but who might be nursing invisible wounds or who might be struggling to cope with invisible disabilities. This past year has given me a new perspective on that by making me aware of my own disabilities, most of which you won't notice if you see me at the gym or in one of my classrooms.

I might not be able to write another book yet, so for now, here's my plan: I'll write a little at a time. Thankfully, I've got my notes, sketches, and photos. I'll start with them.

If you're curious about how a professor of philosophy and classics does research and writing about nature - and how he works to recover from a serious brain injury - you might check out some of my recent publications. My book Downstream is the result of eight years of field research on the ecology of the Appalachians, with a focus on brook trout. On this blog you'll also find my recently published poem, "Sage Creek," which might give you a glimpse of my ancient philosophy class camping and stargazing in the Badlands. Or feel free to look at my photos on Instagram. Even when I can't teach in the field, I can still wander my garden with a hand lens and camera.

∞

South Fork, Eagle River

After breakfast we put sack lunches in the cooler and threw our backpacks in the fifteen-passenger van. Half an hour later we were piling out at the state park on the South Fork of the Eagle River.

The houses here are ugly. Taken on their own, any one of them is a beautiful building. Plainly this is spendy real estate in God’s country. But the houses look like they were lifted from the pages of some little-boxes-full-of-ticky-tacky architectural lust propaganda and carpet-bombed on the hillside, then allowed to remain wherever they fell. There is no order, no sense that the houses were built for the place. Every one of them is a garish, angular excrescence on the opposite hillside. No doubt their inmates would disagree with my assessment; they only see the houses up close, and from the inside. They must have no idea how out of place their unnatural rectangles look against the sweeping slope of the Chugach Range. No doubt, when you’re on the other side of those big plates of glass, gazing over here at the state park over your morning K-cup, the view is precious. But when you’re in the state park, looking back, there is nothing on the opposite hillside to love. Over here, there is only regret that these people believed that you could buy both the land and the landscape.

It’s about three miles’ hike in to first bridge in state park. A fairly easy up-and-down walk. It’s raining. Spitting, really, what they call chipichipi in Guatemala, a constant drizzle. The sky is a palette of cottony grays that have lowered themselves onto the mountaintops. There is a clear line below which the mountains are visible. Above it, clouds roll and shift.

I shiver a little in my heavy raincoat and think about putting on my rain pants, but I know I’ll be too hot if I do. Some of my students are wearing shorts.

At the footbridge we sit and eat our lunches. The university has packed us red delicious apples (a mendacious name), bags of honey Dijon potato chips, and turkey sandwiches with lettuce and onions. It’s not good turkey, but no one cares. This is a lovely place. We have other food in this place.

The river is only fifteen feet wide here, and it is the color of chalk, like diluted Milk of Magnesia. Taking off my shoes, I wade in. Immediately my feet start to ache with cold. Turning over a stone, I look at its underside. The gray water drips off and a tiny larva wriggles to get out of the light. It's too small to identify it, maybe a miniscule stonefly. A huge blue dragonfly cruises over the river, darting past me.

There are lots of wildflowers up here. One of my students is on the ground with her laminated guidebook, puzzling over one specimen. I've been carrying these guides everywhere, but they're only helpful for about seventy-five percent of the common stuff. There's just too much life here to get it all in a book.

The flowers grow in so many colors, so many strategies for getting the scarce pollinators' attention in the brief summer. Yellows, purples, and blues predominate. The guidebook warns me about several of the purples: DO NOT EAT THIS! Some of them are poisonous. So are a few of the yellows. This is a beautiful place, but it's also a harsh place, and life clings to the edge. Poison is one good way not to get eaten, I suppose. Looking up the mountain, the trees give way to shrubs a hundred yards above us. A hundred yards more and there's only grass. Above that, I can only see rock.

Some of these plants have another strategy: rather than avoiding getting eaten, they invite it. Berries are the way some plants make use of animals to carry their seeds to new places. Bear scat, full of seeds, is all along the trails here. Each mound is a nursery where some new plant may grow in the fertile dung.

There is a kind of berry like a blueberry that grows on something that looks like a mix between evergreens and moss, only a few inches high. Some people call it "mossberry," appropriately. Some locals call it a blackberry. Matt tells us they're crowberries, as he gathers a handful. He eats some and then the students tentatively pick and eat some too.

We spend three hours there at the bridge, observing. There's so much to see. Some of us write, some draw, some stare at the peaks that surround us. A few doze off. I get out my watercolors and try to paint the landscape, but I'm quickly frustrated. There are so many greens and grays and blues, and I'm no good at mixing colors. I keep painting anyway. I can at least try to get the shapes right, I think, but I'm wrong about that, too. The mountains are stacked up in layers, and the lines look clean and clear at first, but when I try to focus on them they blur into one another. The hanging glacier at the end of the valley looms over us, silent and white and yet so eloquent. The glaciers are what made all of this, and even though they have retreated, the river runs with their tillage, the plants grow in their finely ground dust, the smooth slopes were ground smooth by millennia of ice.

Upstream, Brenden hooks his first-ever dolly varden. This is his first fish in Alaska. He is positively glowing with delight. He cradles it in his hand and then quickly returns it to the water pausing only to admire this vibrant glacial relic of a char. It too depends on the glacier.

The temperature is constantly shifting as the sun comes in and out of the clouds. Each part of the valley takes its turn being illuminated: the river shines like silver; the mountainside glows bright green and the rocks and bushes above the tree line cast sharp shadows; high in the valley small glaciers are bright ribbons streaking the blue granite. The clouds push the sunlight in ribbons across the valley. When we are suddenly in the light, we are warm.

After a few hours we walk back to the car. No one wants to go. For a while we drive in luminous silence.

The houses here are ugly. Taken on their own, any one of them is a beautiful building. Plainly this is spendy real estate in God’s country. But the houses look like they were lifted from the pages of some little-boxes-full-of-ticky-tacky architectural lust propaganda and carpet-bombed on the hillside, then allowed to remain wherever they fell. There is no order, no sense that the houses were built for the place. Every one of them is a garish, angular excrescence on the opposite hillside. No doubt their inmates would disagree with my assessment; they only see the houses up close, and from the inside. They must have no idea how out of place their unnatural rectangles look against the sweeping slope of the Chugach Range. No doubt, when you’re on the other side of those big plates of glass, gazing over here at the state park over your morning K-cup, the view is precious. But when you’re in the state park, looking back, there is nothing on the opposite hillside to love. Over here, there is only regret that these people believed that you could buy both the land and the landscape.

It’s about three miles’ hike in to first bridge in state park. A fairly easy up-and-down walk. It’s raining. Spitting, really, what they call chipichipi in Guatemala, a constant drizzle. The sky is a palette of cottony grays that have lowered themselves onto the mountaintops. There is a clear line below which the mountains are visible. Above it, clouds roll and shift.

I shiver a little in my heavy raincoat and think about putting on my rain pants, but I know I’ll be too hot if I do. Some of my students are wearing shorts.