architecture

- This too is related to technology, of course. If the class is focused on video screens, then all the chairs will face the screens, and the classroom might even be structured like a theater. Etymologically, "theater" means something like "a place of gazing," and theaters tend to encourage people to gaze. Sometimes this can work against other activities, like colloquy, small-group interaction, and really anything that involves students moving from one place to another.

- If that last sentence made you ask,"But why do you want your students to move from one place to another?" then you see that we have some pretty strong presuppositions about how education should happen: students should sit and listen, teachers should stand and lecture. This communicates something about authority, and at times that's helpful. But it can also invite students to lean back into passivity, and to assume they have no role in their own education.

- The furniture in classrooms tells us how people are to behave, because it has been made and purchased by people who had in mind some idea of how students should behave. Most wrap-around desks are made for right-handed people, for instance. And most classroom desks I've seen expect students to sit upright, at attention, with a book open in front of them. I really don't like those desks, and I feel trapped when I sit in them. I wonder sometimes how they make my students feel. I wish we had fewer chairs and more sofas. Maybe a fireplace, or some tables with glasses of water, and ashtrays on them. I suppose I wish I could teach in pubs or ratskellers, which are, after all, places consciously designed for people to meet and discuss what most matters to them, informally, passionately, amicably.

- Classrooms that privilege video screens tend to undervalue natural light and windows. I am reminded of Emerson's reflection on a boring sermon he once heard. Emerson wrote, in his Divinity School Address, that while the minister droned on, Emerson looked out the window at the falling snow, which, he proclaimed, preached a better sermon than the minister. I have no doubt that nature can often give a better lecture than I can.

∞

On The Religious Architecture of Water

One of my recent articles on Medium. Here's a sample:

If you want to know what someone believes, don’t ask them what they believe. Ask them where they spend their time, energy, and money.

Because the things that we genuinely believe are things we act on.

The

result is that over time our deepest beliefs wind up taking on concrete

forms. One pebble at a time, we build mounds and walls. One small

decision after another adds on to long history of similar decisions.

And soon the landscape around us becomes the outward form of our inward beliefs.

∞

Bluejay Linings

"Well, look at the silver lining!"

An accident two years ago left me with some injuries that occasionally keep me from doing what I would like to do. I shouldn't complain; my life's pretty good. But even little pains seem to draw all my attention. If my whole body is fine but I've got a blister on my small toe, I can forget the beautiful landscape I'm in and focus instead on the blister, or on the hiking boots that rubbed too much while I climbed a once-in-a-lifetime mountain. A splinter in my finger gets more of my attention than my wife's hand in mine does. Even small pain can keep my mind from noticing great loveliness.

Occasionally, my injuries keep me from being able to drive. When I cannot drive I rely on bicycling, and then I see much more clearly how much my city has been shaped by the automobile. We have very few taxis, and not much by way of public transit. Our city is in a place where land is cheap and abundant, and the sprawling grid of streets and of wide green lawns is a response to the availability of land: it's not a walking city, it's a city for driving. There are some nice bike trails, but they're mostly an afterthought that are designed for recreation and not for transportation. Here in Sioux Falls, the private car rules the road.

I own several cars, and my cars are also a response to the land here, and to its weather. The open prairie can get very cold in winter, and very hot in the summer. In my lifetime, automobiles have become better and better at insulating me from the extremes of weather. I can drive a thousand miles without feeling the air other than when I stop for rest or fuel. This usually seems like an advantage. Sometimes I wish I could talk with other drivers, but we are insulated from one another, too.

A few days ago someone told me that having to rely on my bicycle is a gift, an advantage. "Look at the silver linings," they said. When you bike, you get exercise! I think they meant to console me, and I'm sure I've said the same kind of thing to others, hoping to boost their spirits by pointing out that things could be worse. And I'll probably wind up doing it again in my lifetime. It's so easy to feel insulated from others' pain, and so hard to know the effects of our words on others. Argh. If I've done that to you, I'm sorry.

*****

Last January, as I walked through the forest of Petén, Guatemala with my students, I kept saying to them the last three lines from Gary Snyder's poem, "For the Children." Those lines form a sort of haiku at the end of a longer poem:

stay together

learn the flowers

go light

I keep returning to that poem. Some of the hills are hard to climb, and I know that some of them will give me blisters. Others...well, someday those once-in-a-lifetime mountains will be climbable only in my memory.

For now, I'm trying not to let the well-intended words about "silver linings" rub me the wrong way, and to take them in the spirit they're offered in. They may be awkward, but they're meant to help.

From my three-wheeled vélo, uninsulated from the weather, I find I am also exposed to the sound of the birds. I haven't learned all the flowers yet, and I'm still working on the birdsongs, but I know many of their voices. In the last month I've learned where the bluejays live in my neighborhood. I didn't know we had bluejays near my house. I've seen them in our city, but only rarely. Now I've found two pair, and I'm starting to figure out which are their favorite trees. As I roll along quietly on my recumbent trike, the birds let me coast past them, eyeing me perhaps, as I listen for them high in the treetops of this prairie town.

∞

Babel, in Paraphrase

Recently I have been wandering my city with a camera and sketchbook, looking at the ways our use and design of spaces speak about what we value.

Seeing often requires unhasty attention, or training, or both. I can't claim to have training in architecture, but I am trained in semiotics, and I suppose some of my grandfather's years as a toolmaker and my father's career as an engineer have rubbed off on me. Whatever the cause, I care about design.

The ancient story of the Tower of Babel (found in the eleventh chapter of the Book of Genesis) is also a story about design, and semiotics.

It's also a story worth unhasty attention. One hasty version goes roughly like this: everyone on earth shared a common language and common vocabulary. The people, moving to a new place, decided to build a tower to heaven, so they baked bricks and began to build. But they did not finish it; their language became many languages, and they spread out in many directions, divided from one another.

The Bible has a number of stories like this, short tales that seem to be making some simple and clear point. But as we ponder them unhastily - which is what theologians often do - we become more aware of how little we know. The obvious becomes the obscure, and the quotidien becomes mysterious.

A simple story becomes an invitation to slow down even more, and to consider. Selah, it says to us.

At first blush, the story of Babel appears to be a story of human hubris, and of God frustrating that hubris. It could be a simple parallel to the expulsion from Eden, or to the flooding of the earth in the story of Noah: there are limits, and if you transgress those limits, you will make your lot in life worse.

Lately, as I've slowed down my reading, I've been noticing something else: the bricks. The Bible does not often talk about the ethics of technology. There are passages that speak of things like the ethics of weaving, of sharing resources, and of the production, preparation, and distribution of food. But there are not many passages that name a particular human invention in the context of ethics. One of those inventions is named in several places: bricks.

The passage in Genesis 11 talks about bricks as a substitute for stone. When I was young I often worked as a stonemason and bricklayer. That experience may be what draws me to this passage. Bricks are easy to make, and easy to cut. We can standardize them, which makes building walls much faster.

The downside of bricks is related to their upside: they're easy to break, or to cut, or to erode. They don't last as long as stone, and if they're not well-reinforced, they are not as resilient against natural disasters. Some ancient stonemasons figured out how to cut and lay stones that can be jostled by an earthquake and then settle back into position, but bricks often collapse when the ground shakes beneath them. Bricks are easy to use, but they are not as reliable as stone. In comparison to many kinds of stone, bricks are a short-term investment.

This makes me wonder: what was the problem with the Tower of Babel? Was it the fact that the people were trying to build a tower to heaven? Or was it that they were trying to build one badly, or cheaply, or fast? Was it a problem of hubris, or a problem of materials and design? Genesis 11 does not answer that question directly. It leaves it as an open question for us.

Which is just what we should expect, if Genesis 11 conveys any truth. Think about this: how would this story have been told before the Tower of Babel was built? If the story is right, then before the Tower was built, the story would have been told in a language everyone would understand. But now that we have tried to build it (whatever that means) the story must be told in words that are confused, for people who are scattered and divided and who do not share vocabulary.

To paraphrase this: somehow, our use of bricks resulted in making it harder to connect with one another. And it's not clear how.

But somehow, it is a story that hundreds of generations have found worth repeating, even if our words fail to say with precision why that is so.

Maybe, just maybe, it has something to do with the way we continue to build walls of bricks. And what those bricks say about us, and what we value.

Since writing this, I started reading Christopher Alexander's book, The Timeless Way of Building, recommended to me by some friends in Sioux Falls. This line in particular stands out as serendipitous:

Seeing often requires unhasty attention, or training, or both. I can't claim to have training in architecture, but I am trained in semiotics, and I suppose some of my grandfather's years as a toolmaker and my father's career as an engineer have rubbed off on me. Whatever the cause, I care about design.

The ancient story of the Tower of Babel (found in the eleventh chapter of the Book of Genesis) is also a story about design, and semiotics.

It's also a story worth unhasty attention. One hasty version goes roughly like this: everyone on earth shared a common language and common vocabulary. The people, moving to a new place, decided to build a tower to heaven, so they baked bricks and began to build. But they did not finish it; their language became many languages, and they spread out in many directions, divided from one another.

The Bible has a number of stories like this, short tales that seem to be making some simple and clear point. But as we ponder them unhastily - which is what theologians often do - we become more aware of how little we know. The obvious becomes the obscure, and the quotidien becomes mysterious.

A simple story becomes an invitation to slow down even more, and to consider. Selah, it says to us.

At first blush, the story of Babel appears to be a story of human hubris, and of God frustrating that hubris. It could be a simple parallel to the expulsion from Eden, or to the flooding of the earth in the story of Noah: there are limits, and if you transgress those limits, you will make your lot in life worse.

The passage in Genesis 11 talks about bricks as a substitute for stone. When I was young I often worked as a stonemason and bricklayer. That experience may be what draws me to this passage. Bricks are easy to make, and easy to cut. We can standardize them, which makes building walls much faster.

The downside of bricks is related to their upside: they're easy to break, or to cut, or to erode. They don't last as long as stone, and if they're not well-reinforced, they are not as resilient against natural disasters. Some ancient stonemasons figured out how to cut and lay stones that can be jostled by an earthquake and then settle back into position, but bricks often collapse when the ground shakes beneath them. Bricks are easy to use, but they are not as reliable as stone. In comparison to many kinds of stone, bricks are a short-term investment.

*****

This makes me wonder: what was the problem with the Tower of Babel? Was it the fact that the people were trying to build a tower to heaven? Or was it that they were trying to build one badly, or cheaply, or fast? Was it a problem of hubris, or a problem of materials and design? Genesis 11 does not answer that question directly. It leaves it as an open question for us.

Which is just what we should expect, if Genesis 11 conveys any truth. Think about this: how would this story have been told before the Tower of Babel was built? If the story is right, then before the Tower was built, the story would have been told in a language everyone would understand. But now that we have tried to build it (whatever that means) the story must be told in words that are confused, for people who are scattered and divided and who do not share vocabulary.

To paraphrase this: somehow, our use of bricks resulted in making it harder to connect with one another. And it's not clear how.

But somehow, it is a story that hundreds of generations have found worth repeating, even if our words fail to say with precision why that is so.

Maybe, just maybe, it has something to do with the way we continue to build walls of bricks. And what those bricks say about us, and what we value.

*****

Update:Since writing this, I started reading Christopher Alexander's book, The Timeless Way of Building, recommended to me by some friends in Sioux Falls. This line in particular stands out as serendipitous:

"But in our time the languages have broken down. Since they are no longer shared, the processes which keep them deep have broken down: and it is therefore virtually impossible for anybody, in our time, to make a building live." (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979) p. 225

∞

South Fork, Eagle River

After breakfast we put sack lunches in the cooler and threw our backpacks in the fifteen-passenger van. Half an hour later we were piling out at the state park on the South Fork of the Eagle River.

The houses here are ugly. Taken on their own, any one of them is a beautiful building. Plainly this is spendy real estate in God’s country. But the houses look like they were lifted from the pages of some little-boxes-full-of-ticky-tacky architectural lust propaganda and carpet-bombed on the hillside, then allowed to remain wherever they fell. There is no order, no sense that the houses were built for the place. Every one of them is a garish, angular excrescence on the opposite hillside. No doubt their inmates would disagree with my assessment; they only see the houses up close, and from the inside. They must have no idea how out of place their unnatural rectangles look against the sweeping slope of the Chugach Range. No doubt, when you’re on the other side of those big plates of glass, gazing over here at the state park over your morning K-cup, the view is precious. But when you’re in the state park, looking back, there is nothing on the opposite hillside to love. Over here, there is only regret that these people believed that you could buy both the land and the landscape.

It’s about three miles’ hike in to first bridge in state park. A fairly easy up-and-down walk. It’s raining. Spitting, really, what they call chipichipi in Guatemala, a constant drizzle. The sky is a palette of cottony grays that have lowered themselves onto the mountaintops. There is a clear line below which the mountains are visible. Above it, clouds roll and shift.

I shiver a little in my heavy raincoat and think about putting on my rain pants, but I know I’ll be too hot if I do. Some of my students are wearing shorts.

At the footbridge we sit and eat our lunches. The university has packed us red delicious apples (a mendacious name), bags of honey Dijon potato chips, and turkey sandwiches with lettuce and onions. It’s not good turkey, but no one cares. This is a lovely place. We have other food in this place.

The river is only fifteen feet wide here, and it is the color of chalk, like diluted Milk of Magnesia. Taking off my shoes, I wade in. Immediately my feet start to ache with cold. Turning over a stone, I look at its underside. The gray water drips off and a tiny larva wriggles to get out of the light. It's too small to identify it, maybe a miniscule stonefly. A huge blue dragonfly cruises over the river, darting past me.

There are lots of wildflowers up here. One of my students is on the ground with her laminated guidebook, puzzling over one specimen. I've been carrying these guides everywhere, but they're only helpful for about seventy-five percent of the common stuff. There's just too much life here to get it all in a book.

The flowers grow in so many colors, so many strategies for getting the scarce pollinators' attention in the brief summer. Yellows, purples, and blues predominate. The guidebook warns me about several of the purples: DO NOT EAT THIS! Some of them are poisonous. So are a few of the yellows. This is a beautiful place, but it's also a harsh place, and life clings to the edge. Poison is one good way not to get eaten, I suppose. Looking up the mountain, the trees give way to shrubs a hundred yards above us. A hundred yards more and there's only grass. Above that, I can only see rock.

Some of these plants have another strategy: rather than avoiding getting eaten, they invite it. Berries are the way some plants make use of animals to carry their seeds to new places. Bear scat, full of seeds, is all along the trails here. Each mound is a nursery where some new plant may grow in the fertile dung.

There is a kind of berry like a blueberry that grows on something that looks like a mix between evergreens and moss, only a few inches high. Some people call it "mossberry," appropriately. Some locals call it a blackberry. Matt tells us they're crowberries, as he gathers a handful. He eats some and then the students tentatively pick and eat some too.

We spend three hours there at the bridge, observing. There's so much to see. Some of us write, some draw, some stare at the peaks that surround us. A few doze off. I get out my watercolors and try to paint the landscape, but I'm quickly frustrated. There are so many greens and grays and blues, and I'm no good at mixing colors. I keep painting anyway. I can at least try to get the shapes right, I think, but I'm wrong about that, too. The mountains are stacked up in layers, and the lines look clean and clear at first, but when I try to focus on them they blur into one another. The hanging glacier at the end of the valley looms over us, silent and white and yet so eloquent. The glaciers are what made all of this, and even though they have retreated, the river runs with their tillage, the plants grow in their finely ground dust, the smooth slopes were ground smooth by millennia of ice.

Upstream, Brenden hooks his first-ever dolly varden. This is his first fish in Alaska. He is positively glowing with delight. He cradles it in his hand and then quickly returns it to the water pausing only to admire this vibrant glacial relic of a char. It too depends on the glacier.

The temperature is constantly shifting as the sun comes in and out of the clouds. Each part of the valley takes its turn being illuminated: the river shines like silver; the mountainside glows bright green and the rocks and bushes above the tree line cast sharp shadows; high in the valley small glaciers are bright ribbons streaking the blue granite. The clouds push the sunlight in ribbons across the valley. When we are suddenly in the light, we are warm.

After a few hours we walk back to the car. No one wants to go. For a while we drive in luminous silence.

The houses here are ugly. Taken on their own, any one of them is a beautiful building. Plainly this is spendy real estate in God’s country. But the houses look like they were lifted from the pages of some little-boxes-full-of-ticky-tacky architectural lust propaganda and carpet-bombed on the hillside, then allowed to remain wherever they fell. There is no order, no sense that the houses were built for the place. Every one of them is a garish, angular excrescence on the opposite hillside. No doubt their inmates would disagree with my assessment; they only see the houses up close, and from the inside. They must have no idea how out of place their unnatural rectangles look against the sweeping slope of the Chugach Range. No doubt, when you’re on the other side of those big plates of glass, gazing over here at the state park over your morning K-cup, the view is precious. But when you’re in the state park, looking back, there is nothing on the opposite hillside to love. Over here, there is only regret that these people believed that you could buy both the land and the landscape.

It’s about three miles’ hike in to first bridge in state park. A fairly easy up-and-down walk. It’s raining. Spitting, really, what they call chipichipi in Guatemala, a constant drizzle. The sky is a palette of cottony grays that have lowered themselves onto the mountaintops. There is a clear line below which the mountains are visible. Above it, clouds roll and shift.

I shiver a little in my heavy raincoat and think about putting on my rain pants, but I know I’ll be too hot if I do. Some of my students are wearing shorts.

At the footbridge we sit and eat our lunches. The university has packed us red delicious apples (a mendacious name), bags of honey Dijon potato chips, and turkey sandwiches with lettuce and onions. It’s not good turkey, but no one cares. This is a lovely place. We have other food in this place.

The river is only fifteen feet wide here, and it is the color of chalk, like diluted Milk of Magnesia. Taking off my shoes, I wade in. Immediately my feet start to ache with cold. Turning over a stone, I look at its underside. The gray water drips off and a tiny larva wriggles to get out of the light. It's too small to identify it, maybe a miniscule stonefly. A huge blue dragonfly cruises over the river, darting past me.

There are lots of wildflowers up here. One of my students is on the ground with her laminated guidebook, puzzling over one specimen. I've been carrying these guides everywhere, but they're only helpful for about seventy-five percent of the common stuff. There's just too much life here to get it all in a book.

The flowers grow in so many colors, so many strategies for getting the scarce pollinators' attention in the brief summer. Yellows, purples, and blues predominate. The guidebook warns me about several of the purples: DO NOT EAT THIS! Some of them are poisonous. So are a few of the yellows. This is a beautiful place, but it's also a harsh place, and life clings to the edge. Poison is one good way not to get eaten, I suppose. Looking up the mountain, the trees give way to shrubs a hundred yards above us. A hundred yards more and there's only grass. Above that, I can only see rock.

Some of these plants have another strategy: rather than avoiding getting eaten, they invite it. Berries are the way some plants make use of animals to carry their seeds to new places. Bear scat, full of seeds, is all along the trails here. Each mound is a nursery where some new plant may grow in the fertile dung.

There is a kind of berry like a blueberry that grows on something that looks like a mix between evergreens and moss, only a few inches high. Some people call it "mossberry," appropriately. Some locals call it a blackberry. Matt tells us they're crowberries, as he gathers a handful. He eats some and then the students tentatively pick and eat some too.

We spend three hours there at the bridge, observing. There's so much to see. Some of us write, some draw, some stare at the peaks that surround us. A few doze off. I get out my watercolors and try to paint the landscape, but I'm quickly frustrated. There are so many greens and grays and blues, and I'm no good at mixing colors. I keep painting anyway. I can at least try to get the shapes right, I think, but I'm wrong about that, too. The mountains are stacked up in layers, and the lines look clean and clear at first, but when I try to focus on them they blur into one another. The hanging glacier at the end of the valley looms over us, silent and white and yet so eloquent. The glaciers are what made all of this, and even though they have retreated, the river runs with their tillage, the plants grow in their finely ground dust, the smooth slopes were ground smooth by millennia of ice.

Upstream, Brenden hooks his first-ever dolly varden. This is his first fish in Alaska. He is positively glowing with delight. He cradles it in his hand and then quickly returns it to the water pausing only to admire this vibrant glacial relic of a char. It too depends on the glacier.

The temperature is constantly shifting as the sun comes in and out of the clouds. Each part of the valley takes its turn being illuminated: the river shines like silver; the mountainside glows bright green and the rocks and bushes above the tree line cast sharp shadows; high in the valley small glaciers are bright ribbons streaking the blue granite. The clouds push the sunlight in ribbons across the valley. When we are suddenly in the light, we are warm.

After a few hours we walk back to the car. No one wants to go. For a while we drive in luminous silence.

∞

On Church Organs and Church Music

Recently I had the good fortune to hear an organ concert in Westminster Abbey. Not long afterwards I heard someone asking whether churches should get rid of their old organs. The question is a reasonable one, since organs are expensive to maintain, nigh impossible to move, and not many people can play them well. To those charges we should add the charge that organs are old-fashioned, and we are not.

I happen to love organ music, so that's one reason why I think we shouldn't get rid of the organs that remain in our churches. But there is at least one more important reason to think carefully about replacing them. Sometimes organs don't fit well with the buildings they are in, as though the organ was purchased on its own merits and not for the way it matched the acoustics of the building that holds it. In those cases, I don't see the loss if they're removed.

But this is a failing of architecture and economics, not just of music. The problem in that case is far greater than the sin of not being contemporary. An organ that does not match the church, or a church that is not made to be acoustically beautiful - both of these are failures, the kind of failure that comes from people who think that design and aesthetics are luxuries. But design is never neutral; it always helps or hurts. Efficiencies and economics can be the enemies of accomplishing the most worthwhile ends.

Here's what Westminster Abbey reminded me of: a well-built organ is not just an instrument; it is a part of the edifice itself. Specifically, it is the part that turns the whole edifice into a musical instrument. When the organ at Westminster is being played, it is not just a keyboard or pipes that are being played, but the whole building. Every bit of the building resounds. The music is not an isolated event anymore; the notes played and the place in which they are played have merged, and each reaches out to affirm the other. A good organ turns a church into a musical instrument.

Too often churches think of aesthetics last, if at all, or refuse to make aesthetics part of their theology. This is a huge mistake. The prophets describe the architectural adornments of the Ark and the Tabernacle and the Temple, giving those aesthetical elements a permanent place in Jewish and Christian canonical scripture. Similarly, the scriptures are full of songs and poems that - one could argue - are unnecessary to salvation. As Scott Parsons and I have argued, art and the sacred belong together. Our faith is not a matter of mere talk; sometimes what must be articulated cannot be said in words, but needs the smell of incense, the ringing of a sanctus bell, the deep bellow of a pipe organ, the beauty of light well-captured in glass or terrazzo.

If you're not sure of what I mean, listen to Árstí∂ir sing the medieval hymn Heyr himna smi∂ur -- in a train station. Can you imagine that being sung in a church with similar acoustics? Here's what I love about the video: when they sing that beautiful old song, everyone around them stops to listen. The beauty of the song is arresting, especially when it is paired with the building. What keeps us from dreaming of building churches, writing music, and designing instruments that could similarly arrest us?

I happen to love organ music, so that's one reason why I think we shouldn't get rid of the organs that remain in our churches. But there is at least one more important reason to think carefully about replacing them. Sometimes organs don't fit well with the buildings they are in, as though the organ was purchased on its own merits and not for the way it matched the acoustics of the building that holds it. In those cases, I don't see the loss if they're removed.

But this is a failing of architecture and economics, not just of music. The problem in that case is far greater than the sin of not being contemporary. An organ that does not match the church, or a church that is not made to be acoustically beautiful - both of these are failures, the kind of failure that comes from people who think that design and aesthetics are luxuries. But design is never neutral; it always helps or hurts. Efficiencies and economics can be the enemies of accomplishing the most worthwhile ends.

Here's what Westminster Abbey reminded me of: a well-built organ is not just an instrument; it is a part of the edifice itself. Specifically, it is the part that turns the whole edifice into a musical instrument. When the organ at Westminster is being played, it is not just a keyboard or pipes that are being played, but the whole building. Every bit of the building resounds. The music is not an isolated event anymore; the notes played and the place in which they are played have merged, and each reaches out to affirm the other. A good organ turns a church into a musical instrument.

Too often churches think of aesthetics last, if at all, or refuse to make aesthetics part of their theology. This is a huge mistake. The prophets describe the architectural adornments of the Ark and the Tabernacle and the Temple, giving those aesthetical elements a permanent place in Jewish and Christian canonical scripture. Similarly, the scriptures are full of songs and poems that - one could argue - are unnecessary to salvation. As Scott Parsons and I have argued, art and the sacred belong together. Our faith is not a matter of mere talk; sometimes what must be articulated cannot be said in words, but needs the smell of incense, the ringing of a sanctus bell, the deep bellow of a pipe organ, the beauty of light well-captured in glass or terrazzo.

[youtube=[www.youtube.com/watch](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e4dT8FJ2GE0&w=320&h=266])

If you're not sure of what I mean, listen to Árstí∂ir sing the medieval hymn Heyr himna smi∂ur -- in a train station. Can you imagine that being sung in a church with similar acoustics? Here's what I love about the video: when they sing that beautiful old song, everyone around them stops to listen. The beauty of the song is arresting, especially when it is paired with the building. What keeps us from dreaming of building churches, writing music, and designing instruments that could similarly arrest us?

∞

As September approaches, people keep asking me, "Are you ready to get back in the classroom?"

As early as middle school I knew I wanted to become a college professor, and I love my job. It is a delight to spend time with young people who are curious, after all.

Years ago, my friend Matt Dickerson pointed out to me that it's also my job to help those who are not curious to see why they should be. As it turns out, that work is usually delightful, too, a rewarding challenge.

So on the whole, I love my work.

But I admit I don't love classrooms, for several reasons:

First, no matter what decade, every classroom I've been in has exhibited an unhealthy tendency towards becoming cluttered with the latest technology, and most of that tech seems to take up a lot of space and to become the center of attention. I'm not opposed to technology in the classroom, not at all. But I'm opposed to letting it get in the way, as it does when the "Smart Cart" leaves me no room for my lecture notes, or when I can't seem to turn the ceiling-mounted projector on or off. I'm a fan of chalk, because chalk allows spontaneity, and it allows for much more than alphanumeric writing in neat rows. Sadly, concerns about chalk dust getting into computers is threatening to make chalkboards disappear from my classrooms. Alas. Chalk is an excellent technology, and if it vanishes, I will mourn its loss.

Second, classroom architecture is not some value-free, neutral design. Classroom architecture makes a big difference in how people teach, and how they learn:

Which is why, as often as I can, I get my students out of the classroom. When we are reading Thoreau's Walking, we go for a walk. When I teach environmental philosophy, we often meet under the great tree in our campus quad, where I encourage students to daydream and to play with the grass, to look for worm-castings and owl pellets, feathers and seed-pods, invertebrates and fallen bits of bark. What good is it to gain the world of theoretical knowledge at the expense of knowledge gained through vital, haptic, bodily experience?

And this is why I am a preacher of the importance of study abroad. Not just travel, but serious, engaged, rigorous study in the classroom of life in another place. This is why I teach Classics in Greece every year, and why year after year I take students to Central America to study environmental philosophy and ecology.

More and more I've been trying to shift the learning focus in my classes from the classroom to the laboratory - where by "laboratory" I mean anywhere that allows students to learn with their whole person. I make my ancient philosophy students devote hours each semester to star-gazing, in part because this is what the ancients did, and in part because I don't want them to miss the stars. I want them to gaze in wonder at the firmament so that when they read Aristotle and Galileo they know that they've looked at what those great minds saw as well. We even occasionally take field trips to really dark places like the South Dakota Badlands so we can see the skies even better.

My environmental philosophy students must observe a square meter of earth for a semester, spending an hour at a time without a camera, drawing and writing about what they see, because it does not make sense to me to talk about the earth when you have not taken the time to sit upon it, to listen to it, to smell and taste it, and to see what other lives creep, and walk, and fly across it.

My friend Aage Jensen advocates the Norwegian philosophy of Friluftsliv, life and education outdoors. And when he organizes a conference on it, he eschews conference centers and holds the conference while walking through the mountains, or paddling a river. Because he believes that one should practice what one preaches, and that nature is always ready to teach.

To paraphrase the Stoic Musonius, teachers would do well to talk less and to take their students with them into the fields, because there they will learn far better and far more than in the lecture hall.

Teaching Outdoors

|

As early as middle school I knew I wanted to become a college professor, and I love my job. It is a delight to spend time with young people who are curious, after all.

Years ago, my friend Matt Dickerson pointed out to me that it's also my job to help those who are not curious to see why they should be. As it turns out, that work is usually delightful, too, a rewarding challenge.

So on the whole, I love my work.

But I admit I don't love classrooms, for several reasons:

First, no matter what decade, every classroom I've been in has exhibited an unhealthy tendency towards becoming cluttered with the latest technology, and most of that tech seems to take up a lot of space and to become the center of attention. I'm not opposed to technology in the classroom, not at all. But I'm opposed to letting it get in the way, as it does when the "Smart Cart" leaves me no room for my lecture notes, or when I can't seem to turn the ceiling-mounted projector on or off. I'm a fan of chalk, because chalk allows spontaneity, and it allows for much more than alphanumeric writing in neat rows. Sadly, concerns about chalk dust getting into computers is threatening to make chalkboards disappear from my classrooms. Alas. Chalk is an excellent technology, and if it vanishes, I will mourn its loss.

Second, classroom architecture is not some value-free, neutral design. Classroom architecture makes a big difference in how people teach, and how they learn:

|

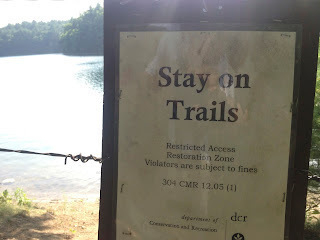

| Step off the trails! Explore! An ironic sign at Walden Pond. |

And this is why I am a preacher of the importance of study abroad. Not just travel, but serious, engaged, rigorous study in the classroom of life in another place. This is why I teach Classics in Greece every year, and why year after year I take students to Central America to study environmental philosophy and ecology.

More and more I've been trying to shift the learning focus in my classes from the classroom to the laboratory - where by "laboratory" I mean anywhere that allows students to learn with their whole person. I make my ancient philosophy students devote hours each semester to star-gazing, in part because this is what the ancients did, and in part because I don't want them to miss the stars. I want them to gaze in wonder at the firmament so that when they read Aristotle and Galileo they know that they've looked at what those great minds saw as well. We even occasionally take field trips to really dark places like the South Dakota Badlands so we can see the skies even better.

My environmental philosophy students must observe a square meter of earth for a semester, spending an hour at a time without a camera, drawing and writing about what they see, because it does not make sense to me to talk about the earth when you have not taken the time to sit upon it, to listen to it, to smell and taste it, and to see what other lives creep, and walk, and fly across it.

My friend Aage Jensen advocates the Norwegian philosophy of Friluftsliv, life and education outdoors. And when he organizes a conference on it, he eschews conference centers and holds the conference while walking through the mountains, or paddling a river. Because he believes that one should practice what one preaches, and that nature is always ready to teach.

To paraphrase the Stoic Musonius, teachers would do well to talk less and to take their students with them into the fields, because there they will learn far better and far more than in the lecture hall.

|

| Nature is full of things worth seeing. |