Aristotle

- This too is related to technology, of course. If the class is focused on video screens, then all the chairs will face the screens, and the classroom might even be structured like a theater. Etymologically, "theater" means something like "a place of gazing," and theaters tend to encourage people to gaze. Sometimes this can work against other activities, like colloquy, small-group interaction, and really anything that involves students moving from one place to another.

- If that last sentence made you ask,"But why do you want your students to move from one place to another?" then you see that we have some pretty strong presuppositions about how education should happen: students should sit and listen, teachers should stand and lecture. This communicates something about authority, and at times that's helpful. But it can also invite students to lean back into passivity, and to assume they have no role in their own education.

- The furniture in classrooms tells us how people are to behave, because it has been made and purchased by people who had in mind some idea of how students should behave. Most wrap-around desks are made for right-handed people, for instance. And most classroom desks I've seen expect students to sit upright, at attention, with a book open in front of them. I really don't like those desks, and I feel trapped when I sit in them. I wonder sometimes how they make my students feel. I wish we had fewer chairs and more sofas. Maybe a fireplace, or some tables with glasses of water, and ashtrays on them. I suppose I wish I could teach in pubs or ratskellers, which are, after all, places consciously designed for people to meet and discuss what most matters to them, informally, passionately, amicably.

- Classrooms that privilege video screens tend to undervalue natural light and windows. I am reminded of Emerson's reflection on a boring sermon he once heard. Emerson wrote, in his Divinity School Address, that while the minister droned on, Emerson looked out the window at the falling snow, which, he proclaimed, preached a better sermon than the minister. I have no doubt that nature can often give a better lecture than I can.

∞

Teaching Tropical Ecology in Belize and Guatemala

Two out of every three January terms my colleague Craig Spencer and I teach a course on tropical ecology in Central America. Right now I'm in the midst of preparing for our next trip there.

In this post I'll try to answer some of the questions that we are often asked about the course. Probably the most common question is "What do you do in your course?" The second most common must be "How can I teach a course like that?" I'll start with the first question:

What do you do in Guatemala and Belize?

The short answer to this question is a lot. I'll try to summarize.

Our approach to tropical ecology includes the standard elements you'd find in any ecology course: our students read a lot about the ecosystems and the prominent species of plants and animals they're likely to encounter. We teach them what we know about the systems we think we understand, and we tell them about the big gaps in our knowledge that we're aware of - knowing full well that we likely have blind spots we aren't aware of.

In Guatemala this means learning about the ecology of a dense forest growing on a karst plateau, and a deep lake where the water does not circulate much.

In Belize we study the mangroves and the barrier reef. The mangroves are like a porous filter between salt and fresh water, like a cell wall on a macro scale. They serve as a buffer against hurricanes; they keep topsoil from eroding into the sea, and they are a rich and colorful nursery for thousands of species.

The Importance of Human Ecology

We want our students to learn much more than the plants, animals, soil, air, and water, though. Perhaps more than anything, we want them to learn the human ecology of the places we visit. Ecology is not merely an academic study; it is, at its heart, the study of both the world and of our place in it. We don't just look at macaws, jaguars, vines, and ceiba trees; we look at the way our lives - even our visit to these amazing places - affect and are affected by these plants and animals. We don't stay in hotels; we rent rooms in local homes, and we eat meals with local people. We hire local teachers to teach us Spanish and the Itzá language. We study the history of the Itzá people, and we visit ancient ruins. We walk through the forest and camp overnight with local guides who can teach us what they know of that place. We spend time playing soccer with a local youth group, we talk with and listen to local teachers, nurses, physicians, forest rangers, ecologists, NGO volunteers, government officials, town elders, and children. If the ecology of the place matters, surely it matters because these people whose ancestors have lived there for so long matter.

In fact, even if you think they don't matter to you, if you're reading this post in North America these people do matter to you. If their ecology suffers, they will be forced to move to look for new sources of income and food. Simple-minded and disingenuous politicians will tell you this is a problem to be solved by erecting a wall on our border, but walls are a partial solution at best, and at worst, they are blinders that keep us from seeing the source of the problem; walls ignore the real illness and conceal the symptoms, as though willful ignorance were good medicine. The real question - in my mind, anyway - is why anyone who lived on the shores of Lake Petén Itzá would ever want to leave. The answer is that people leave beautiful homes when those homes cease to be liveable. Which means the medicine that is needed is one that treats the illness itself, and not just the symptoms. My students (I hope) return from our course no longer able to see Guatemalan immigrants to the United States as a mere abstraction. Break bread in someone's home and you will see that they are human, too, with lives as particular and intricate and important and rooted as your own. Only when we disturb those roots and strip away the soil must the lives be transplanted.

This is what I mean by human ecology.

Where do you go?

Our time in Guatemala is chiefly in central and northern Petén. Until recently, the landscape of northern Petén was dominated by dense forest, mostly old-growth lowland forests. Surface water is mostly wetlands that vary considerably from one season to the next. There are several small-to-medium-sized rivers, and small streams, but I think a good deal of the water flows underground in karst formations; the Petén has thin soil over a wide karst plateau. There is not much water flowing on the surface. In the center of Petén there is one very deep lake, Lake Petén Itzá. This is a gem in the forest. Flying over it on a sunny day you can see the shallows fade from pale green to rich emerald, and the depths along the north side of the lake plunge to amethyst and dark sapphire. The lake has no obvious inflow or outflow, except a few small streams flowing in from the south and west, and a little creek flowing out in the east.

In Belize we spend most of our time on one of the barrier islands that have no permanent residents. We use that island as a home base from which we can boat out to patch reefs, mangroves, turtle grass beds, deep channels, and the fore-reef. We snorkel with our students in all these places, slowly gathering experiences of similar species in diverse environments, so that the students (and we) can see both the ecology of small places and the web of relations between those small places. In mangroves, for instance, we might see juvenile caribbean reef squid that are a few inches long. When we see them on patch reefs, they might be five or six inches long, and in deep water they might reach eight inches. Each location gives us a glimpse of another stage of their life cycle.

Why do you do this? Aren't you a Humanities professor?

Even if people don't often ask me this, it's obvious that quite a few people think it. Yes, I'm a professor of philosophy and classics, and I teach religion courses, too. But for my whole life I have been fascinated by life underwater. My most recent book was the result of eight years of researching the lives of brook trout in the Appalachian mountains, and much of my research now has to do with ocean and riparian environments in Alaska. I don't do much of what would count as research in the natural sciences, but I do spend a lot of time observing nature. This is both because I find it beautiful, and because I think it's a bad idea to try to formulate ethical principles about things I haven't experienced or seen firsthand. Of course it's not impossible to write policies about things one hasn't done; one needn't commit larceny before writing a law prohibiting theft. But experience teaches me things I might not learn in other ways, and that can keep me from trusting too much in my own opinions. As Aristotle put it,

How Can I Teach A Course Like This? Can others participate in this trip?

The answer to the second of these questions is both yes and no. When I'm in Guatemala and Belize, I'm teaching. Unfortunately, this means I don't have time to bring others along and act as their tour guide.

However, the people I work with in Guatemala - the Asociación Bio-Itzá - would be happy to have you come for a visit. They're in the small town of San Josè, Petèn, Guatemala, right on the north shores of the lake. And this is the answer to the first question. Want to teach such a course? Get in touch with Bio-Itzá and they can help you set it up.

You can get to San José by flying or driving to Flores, then going around the lake by bus or car to San José, about a twenty minute drive.

In San José they have a traditional community medicinal garden. Just north of town is the Bio-Itzá Reserve, where you can go for guided walking tours or overnight stays. It's rustic and gorgeous. (Visits to the Reserve must be arranged in advance through Bio-Itzá.)

When you stay in San José you can easily take a launch (a wooden motor boat) across the lake to Flores, the seat of Nojpetén or Tayasal, the last Maya kingdom that fell to the Spanish.

Flores is a pretty place as well, and I like to take my students to visit ARCAS to see their animal rehabilitation center. (There's a great documentary about that place that was on PBS this year called "Jungle Animal Hospital.")

If you stay in San José, you can also take a short trip (about a half hour by car) to Tikal, or to Yaxhá, both of which are amazingly well-preserved Maya ruins. A little further past Tikal is Uaxactún, where you can see more ruins, and you can also visit a community that is trying to practice sustainable forestry.

This region is not like the tourist areas of Western Guatemala; it's more like the rural frontier of Guatemala, a long-neglected place that is now at risk of being overrun by slash-and-burn forestry, cattle farms, and oil development. It makes me think of the Dakotas over the last century; the population is small and indigenous, and most people in power in Guatemala seem to consider the forest to be a wasteland that is better burned down than preserved. I do not share that view, and while I know that more tourism will bring development and other risks to both culture and forest, the risks are already there in other forms. I hope that ecotourism will offer some counterweight to the other kinds of development that don't seek to preserve the biological integrity or cultural history of this place.

|

| Sunrise on the Barrier Reef in Belize |

In this post I'll try to answer some of the questions that we are often asked about the course. Probably the most common question is "What do you do in your course?" The second most common must be "How can I teach a course like that?" I'll start with the first question:

What do you do in Guatemala and Belize?

The short answer to this question is a lot. I'll try to summarize.

Our approach to tropical ecology includes the standard elements you'd find in any ecology course: our students read a lot about the ecosystems and the prominent species of plants and animals they're likely to encounter. We teach them what we know about the systems we think we understand, and we tell them about the big gaps in our knowledge that we're aware of - knowing full well that we likely have blind spots we aren't aware of.

In Guatemala this means learning about the ecology of a dense forest growing on a karst plateau, and a deep lake where the water does not circulate much.

In Belize we study the mangroves and the barrier reef. The mangroves are like a porous filter between salt and fresh water, like a cell wall on a macro scale. They serve as a buffer against hurricanes; they keep topsoil from eroding into the sea, and they are a rich and colorful nursery for thousands of species.

The Importance of Human Ecology

We want our students to learn much more than the plants, animals, soil, air, and water, though. Perhaps more than anything, we want them to learn the human ecology of the places we visit. Ecology is not merely an academic study; it is, at its heart, the study of both the world and of our place in it. We don't just look at macaws, jaguars, vines, and ceiba trees; we look at the way our lives - even our visit to these amazing places - affect and are affected by these plants and animals. We don't stay in hotels; we rent rooms in local homes, and we eat meals with local people. We hire local teachers to teach us Spanish and the Itzá language. We study the history of the Itzá people, and we visit ancient ruins. We walk through the forest and camp overnight with local guides who can teach us what they know of that place. We spend time playing soccer with a local youth group, we talk with and listen to local teachers, nurses, physicians, forest rangers, ecologists, NGO volunteers, government officials, town elders, and children. If the ecology of the place matters, surely it matters because these people whose ancestors have lived there for so long matter.

|

| Tikal |

|

| The church in San José, Petén, Guatemala |

In fact, even if you think they don't matter to you, if you're reading this post in North America these people do matter to you. If their ecology suffers, they will be forced to move to look for new sources of income and food. Simple-minded and disingenuous politicians will tell you this is a problem to be solved by erecting a wall on our border, but walls are a partial solution at best, and at worst, they are blinders that keep us from seeing the source of the problem; walls ignore the real illness and conceal the symptoms, as though willful ignorance were good medicine. The real question - in my mind, anyway - is why anyone who lived on the shores of Lake Petén Itzá would ever want to leave. The answer is that people leave beautiful homes when those homes cease to be liveable. Which means the medicine that is needed is one that treats the illness itself, and not just the symptoms. My students (I hope) return from our course no longer able to see Guatemalan immigrants to the United States as a mere abstraction. Break bread in someone's home and you will see that they are human, too, with lives as particular and intricate and important and rooted as your own. Only when we disturb those roots and strip away the soil must the lives be transplanted.

This is what I mean by human ecology.

|

| One of my students examining and being examined by nature |

Where do you go?

Our time in Guatemala is chiefly in central and northern Petén. Until recently, the landscape of northern Petén was dominated by dense forest, mostly old-growth lowland forests. Surface water is mostly wetlands that vary considerably from one season to the next. There are several small-to-medium-sized rivers, and small streams, but I think a good deal of the water flows underground in karst formations; the Petén has thin soil over a wide karst plateau. There is not much water flowing on the surface. In the center of Petén there is one very deep lake, Lake Petén Itzá. This is a gem in the forest. Flying over it on a sunny day you can see the shallows fade from pale green to rich emerald, and the depths along the north side of the lake plunge to amethyst and dark sapphire. The lake has no obvious inflow or outflow, except a few small streams flowing in from the south and west, and a little creek flowing out in the east.

|

| My students leap into Lake Petén Itzá to cool off. |

In Belize we spend most of our time on one of the barrier islands that have no permanent residents. We use that island as a home base from which we can boat out to patch reefs, mangroves, turtle grass beds, deep channels, and the fore-reef. We snorkel with our students in all these places, slowly gathering experiences of similar species in diverse environments, so that the students (and we) can see both the ecology of small places and the web of relations between those small places. In mangroves, for instance, we might see juvenile caribbean reef squid that are a few inches long. When we see them on patch reefs, they might be five or six inches long, and in deep water they might reach eight inches. Each location gives us a glimpse of another stage of their life cycle.

|

| My students watch the sunset in Belize |

Why do you do this? Aren't you a Humanities professor?

Even if people don't often ask me this, it's obvious that quite a few people think it. Yes, I'm a professor of philosophy and classics, and I teach religion courses, too. But for my whole life I have been fascinated by life underwater. My most recent book was the result of eight years of researching the lives of brook trout in the Appalachian mountains, and much of my research now has to do with ocean and riparian environments in Alaska. I don't do much of what would count as research in the natural sciences, but I do spend a lot of time observing nature. This is both because I find it beautiful, and because I think it's a bad idea to try to formulate ethical principles about things I haven't experienced or seen firsthand. Of course it's not impossible to write policies about things one hasn't done; one needn't commit larceny before writing a law prohibiting theft. But experience teaches me things I might not learn in other ways, and that can keep me from trusting too much in my own opinions. As Aristotle put it,

“Lack of experience diminishes our power of taking a comprehensive view of the admitted facts. Hence those who dwell in intimate association with nature and its phenomena grow more and more able to formulate, as the foundations of their theories, principles such as to admit of a wide and coherent development: while those whom devotion to abstract discussions has rendered unobservant of the facts are too ready to dogmatize on the basis of a few observations.” Aristotle, De Generatione et corruptione, 316a5-10 (Basic Works, McKeon, trans.)I want to "dwell in intimate association of nature and its phenomena," and being able to formulate better principles is a nice side effect of doing so.

How Can I Teach A Course Like This? Can others participate in this trip?

The answer to the second of these questions is both yes and no. When I'm in Guatemala and Belize, I'm teaching. Unfortunately, this means I don't have time to bring others along and act as their tour guide.

However, the people I work with in Guatemala - the Asociación Bio-Itzá - would be happy to have you come for a visit. They're in the small town of San Josè, Petèn, Guatemala, right on the north shores of the lake. And this is the answer to the first question. Want to teach such a course? Get in touch with Bio-Itzá and they can help you set it up.

You can get to San José by flying or driving to Flores, then going around the lake by bus or car to San José, about a twenty minute drive.

|

| Flores, Petén, Guatemala |

In San José they have a traditional community medicinal garden. Just north of town is the Bio-Itzá Reserve, where you can go for guided walking tours or overnight stays. It's rustic and gorgeous. (Visits to the Reserve must be arranged in advance through Bio-Itzá.)

When you stay in San José you can easily take a launch (a wooden motor boat) across the lake to Flores, the seat of Nojpetén or Tayasal, the last Maya kingdom that fell to the Spanish.

Flores is a pretty place as well, and I like to take my students to visit ARCAS to see their animal rehabilitation center. (There's a great documentary about that place that was on PBS this year called "Jungle Animal Hospital.")

|

| Scarlet macaws being rehabilitated at ARCAS so they can be released back into the wild |

If you stay in San José, you can also take a short trip (about a half hour by car) to Tikal, or to Yaxhá, both of which are amazingly well-preserved Maya ruins. A little further past Tikal is Uaxactún, where you can see more ruins, and you can also visit a community that is trying to practice sustainable forestry.

This region is not like the tourist areas of Western Guatemala; it's more like the rural frontier of Guatemala, a long-neglected place that is now at risk of being overrun by slash-and-burn forestry, cattle farms, and oil development. It makes me think of the Dakotas over the last century; the population is small and indigenous, and most people in power in Guatemala seem to consider the forest to be a wasteland that is better burned down than preserved. I do not share that view, and while I know that more tourism will bring development and other risks to both culture and forest, the risks are already there in other forms. I hope that ecotourism will offer some counterweight to the other kinds of development that don't seek to preserve the biological integrity or cultural history of this place.

∞

SPUnK: The Society for the Preservation of Unnecessary Knowledge

My brilliant and curious student James Jennings was interviewed by the brilliant and curious Hugh Weber on South Dakota Public Broadcasting's Dakota Midday.

James is a Philosophy and Classics major at Augustana University, and he's also the Prime Minister of SPUnK, a campus group I advise at Augustana University.

SPUnK - the Society for the Preservation of Unnecessary Knowledge - is devoted to learning about things we don't need to learn about, because we think unnecessary knowledge is worth preserving and promoting. We distinguish between those things students are told they must study in order to get a job, and those things that we study because there is delight in wonder, and in learning new things, even if we don't yet see their practical use. As both Plato's Socrates and Aristotle pointed out, the love of wisdom begins in wonder, and we seek knowledge not for some simple or material gain but for the satisfaction of wonder and out of a desire to know. Here's Aristotle:

This is what SPUnK is all about.

James and Hugh will teach you about paper towns, curiosity, education, Abraham Flexner, Albert Einstein, Rubik's Cubes, and other unnecessary knowledge. It's a short interview, well worth a few minutes of your time. Unnecessary knowledge is worth quite a lot more than a little of our time, after all.

* For two places Plato and Aristotle say this, see Plato's Theaetetus 155b and Aristotle's Metaphysics 982b.)

** Peirce writes about this in the first chapter of Justus Buchler's The Philosophical Writings of Peirce.

James is a Philosophy and Classics major at Augustana University, and he's also the Prime Minister of SPUnK, a campus group I advise at Augustana University.

SPUnK - the Society for the Preservation of Unnecessary Knowledge - is devoted to learning about things we don't need to learn about, because we think unnecessary knowledge is worth preserving and promoting. We distinguish between those things students are told they must study in order to get a job, and those things that we study because there is delight in wonder, and in learning new things, even if we don't yet see their practical use. As both Plato's Socrates and Aristotle pointed out, the love of wisdom begins in wonder, and we seek knowledge not for some simple or material gain but for the satisfaction of wonder and out of a desire to know. Here's Aristotle:

"Now he who wonders and is perplexed feels that he is ignorant (thus the myth-lover is in a sense a philosopher, since myths are composed of wonders); therefore if it was to escape ignorance that men studied philosophy, it is obvious that they pursued science for the sake of knowledge, and not for any practical utility.The actual course of events bears witness to this; for speculation of this kind began with a view to recreation and pastime, at a time when practically all the necessities of life were already supplied. Clearly then it is for no extrinsic advantage that we seek this knowledge; for just as we call a man independent who exists for himself and not for another, so we call this the only independent science, since it alone exists for itself."*Or, as Charles Peirce once put it, science is the practice of those who desire to find things out.**

This is what SPUnK is all about.

James and Hugh will teach you about paper towns, curiosity, education, Abraham Flexner, Albert Einstein, Rubik's Cubes, and other unnecessary knowledge. It's a short interview, well worth a few minutes of your time. Unnecessary knowledge is worth quite a lot more than a little of our time, after all.

*****

* For two places Plato and Aristotle say this, see Plato's Theaetetus 155b and Aristotle's Metaphysics 982b.)

** Peirce writes about this in the first chapter of Justus Buchler's The Philosophical Writings of Peirce.

∞

A Pretty Good Year

Last year was a pretty good year. Or at least, what I remember of it was pretty good.

As my regular readers know, I'm a professor of philosophy and classics, and I teach a wide range of classes. (You can click on the "Teaching" link above to see a sampling of the courses I teach.)

Often people assume that means I wear tweed and a bowtie and that I spend my time in classrooms talking about old books. All that is true, but it's only a part of what I do.

In fact, most of my favorite classrooms are outdoors, where I'm likely to be found wearing jeans and hiking boots, a parka, or a wetsuit and snorkel.

Over the last dozen years or so my teaching and research have tended towards the environmental humanities. Think of this as the merging of the humanities side of the liberal arts with a close observation of the natural world. I consider my work to be a continuation of the work that Thales and Aristotle did when they paid close attention to animals on the ground and to the skies above, and of the work of Peirce, Thoreau, and Bugbee, all of whom let a rising trout or a solar eclipse provoke philosophical reflection.

While I don't work in an indoor laboratory, I think that education is not about the imparting of information or the filling of an empty vessel with ideas. Education is the kindling of a fire, as Plutarch wrote. And that fire is kindled by the kinds of experiences that we get in labs, art studios, shared meals, liturgies, study travel, and seminars. Lecture halls are a fine place to discuss environmental policy, to be sure. But so is a prairie, especially when you're waiting for water to boil on your camp stove, and watching the sun's beams break over the horizon and melt a light frost on your tent.

When I'm at home, I like to take my classes outside to sit under trees on campus. In the fall, I try to bring my Ancient Philosophy students camping in the Badlands of South Dakota where we can view the stars far from urban glow. Most Januaries, my students and I are in the subtropical forests of Guatemala and on a barrier island in Belize, studying ecology and culture. I rarely take a spring break, since I usually take that week to teach a course in Greece. Last summer I started teaching a class on trout and salmon in Alaska.

Those are all beautiful, memorable places, but I don't visit them as a tourist. I go to these places because I want my students to understand what is at stake when we talk about environmental regulations and practices. I want them to meet displaced people whose permafrost islands are melting or whose forests are being burned down for meager cropland. I want them to see the disappearing mangroves so that they can consider the full cost of seafood. When they stay in homes in Guatemala, my students will meet people who can never again be a mere abstraction; after we return, my students will know that the people struggling to cross borders are not nameless, faceless strangers, but people who are looking for ways to feed those they love.

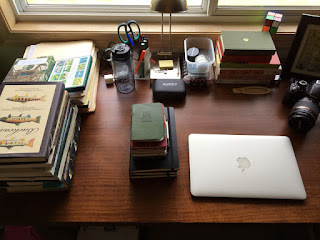

A little less than a year ago I was finishing up a year that had brought me to all these places. I taught in the South Dakota Badlands, in Central America, in Greece, and in Alaska. Along the way, I had begun studying environmental law at Vermont Law School as a way of enhancing my teaching and my research. It was a good year, and as August was winding down, my desk was covered with field notebooks full of observations from Alaska and Guatemala, ready to be written up. My field notes are usually accompanied by thousands of photographs, and hundreds of sketches. I began the fall semester last year ready to teach, and ready to write.

And then I wound up in the hospital with some serious injuries. Those injuries put a sudden stop to all my teaching last fall, and for a long time I lost most of my ability to write. (I'll try to write more about the injuries and my subsequent disabilities later; it's not an easy thing to write about yet.)

Now, as this summer hastens towards the beginning of another school year, I am able to look back on last year with a sense of good fortune - albeit mixed with one very bad day and its long-term consequences. Physically, I'm regaining my flexibility and strength, a little at a time. I'm not where I was a year ago, and I may never be there again, but I'm alive and able to walk, so I'll count that in the "win" column of my life's scorecard. Intellectually, most people seem to think I'm doing fine, so I'll also count that as a win. Although it left me exhausted each day, I was able to teach again this spring, and I plan to be back in my classrooms (Deo volente!) this fall.

But here are these field notebooks, and hundreds of unedited pages on my hard drive. It was my habit to write daily. Over the last year, recovering from a brain injury has made it hard to write more than a few sentences at a time.

This morning I was looking at some of my pictures from my research in the Arctic last summer, and I was hit with a feeling of loss. Those photos and those notes should be a book by now, and perhaps several articles and book chapters, too. Instead, over the last year, as I have waited for my body and brain to heal, and as I struggled to do my teaching, I had no strength to write.

It feels funny to say that, but perhaps I am not alone in finding that a brain injury can be slow to heal and extremely tiring. I don't say that to get your sympathy. I am blessed with a very supportive community and an amazing wife who somehow has kept our life together and nursed me through my healing process. I'm fortunate. But if you've read this far, you might consider whether there are others around you who look like they're doing well physically but who might be nursing invisible wounds or who might be struggling to cope with invisible disabilities. This past year has given me a new perspective on that by making me aware of my own disabilities, most of which you won't notice if you see me at the gym or in one of my classrooms.

I might not be able to write another book yet, so for now, here's my plan: I'll write a little at a time. Thankfully, I've got my notes, sketches, and photos. I'll start with them.

If you're curious about how a professor of philosophy and classics does research and writing about nature - and how he works to recover from a serious brain injury - you might check out some of my recent publications. My book Downstream is the result of eight years of field research on the ecology of the Appalachians, with a focus on brook trout. On this blog you'll also find my recently published poem, "Sage Creek," which might give you a glimpse of my ancient philosophy class camping and stargazing in the Badlands. Or feel free to look at my photos on Instagram. Even when I can't teach in the field, I can still wander my garden with a hand lens and camera.

As my regular readers know, I'm a professor of philosophy and classics, and I teach a wide range of classes. (You can click on the "Teaching" link above to see a sampling of the courses I teach.)

Often people assume that means I wear tweed and a bowtie and that I spend my time in classrooms talking about old books. All that is true, but it's only a part of what I do.

In fact, most of my favorite classrooms are outdoors, where I'm likely to be found wearing jeans and hiking boots, a parka, or a wetsuit and snorkel.

Over the last dozen years or so my teaching and research have tended towards the environmental humanities. Think of this as the merging of the humanities side of the liberal arts with a close observation of the natural world. I consider my work to be a continuation of the work that Thales and Aristotle did when they paid close attention to animals on the ground and to the skies above, and of the work of Peirce, Thoreau, and Bugbee, all of whom let a rising trout or a solar eclipse provoke philosophical reflection.

While I don't work in an indoor laboratory, I think that education is not about the imparting of information or the filling of an empty vessel with ideas. Education is the kindling of a fire, as Plutarch wrote. And that fire is kindled by the kinds of experiences that we get in labs, art studios, shared meals, liturgies, study travel, and seminars. Lecture halls are a fine place to discuss environmental policy, to be sure. But so is a prairie, especially when you're waiting for water to boil on your camp stove, and watching the sun's beams break over the horizon and melt a light frost on your tent.

When I'm at home, I like to take my classes outside to sit under trees on campus. In the fall, I try to bring my Ancient Philosophy students camping in the Badlands of South Dakota where we can view the stars far from urban glow. Most Januaries, my students and I are in the subtropical forests of Guatemala and on a barrier island in Belize, studying ecology and culture. I rarely take a spring break, since I usually take that week to teach a course in Greece. Last summer I started teaching a class on trout and salmon in Alaska.

Those are all beautiful, memorable places, but I don't visit them as a tourist. I go to these places because I want my students to understand what is at stake when we talk about environmental regulations and practices. I want them to meet displaced people whose permafrost islands are melting or whose forests are being burned down for meager cropland. I want them to see the disappearing mangroves so that they can consider the full cost of seafood. When they stay in homes in Guatemala, my students will meet people who can never again be a mere abstraction; after we return, my students will know that the people struggling to cross borders are not nameless, faceless strangers, but people who are looking for ways to feed those they love.

A little less than a year ago I was finishing up a year that had brought me to all these places. I taught in the South Dakota Badlands, in Central America, in Greece, and in Alaska. Along the way, I had begun studying environmental law at Vermont Law School as a way of enhancing my teaching and my research. It was a good year, and as August was winding down, my desk was covered with field notebooks full of observations from Alaska and Guatemala, ready to be written up. My field notes are usually accompanied by thousands of photographs, and hundreds of sketches. I began the fall semester last year ready to teach, and ready to write.

|

| Field notes. A picture of some of the work I do when I'm inside, and not teaching; or, if you like, a picture of my desk as I recover from my injuries. I have a lot of catching up to do. |

And then I wound up in the hospital with some serious injuries. Those injuries put a sudden stop to all my teaching last fall, and for a long time I lost most of my ability to write. (I'll try to write more about the injuries and my subsequent disabilities later; it's not an easy thing to write about yet.)

Now, as this summer hastens towards the beginning of another school year, I am able to look back on last year with a sense of good fortune - albeit mixed with one very bad day and its long-term consequences. Physically, I'm regaining my flexibility and strength, a little at a time. I'm not where I was a year ago, and I may never be there again, but I'm alive and able to walk, so I'll count that in the "win" column of my life's scorecard. Intellectually, most people seem to think I'm doing fine, so I'll also count that as a win. Although it left me exhausted each day, I was able to teach again this spring, and I plan to be back in my classrooms (Deo volente!) this fall.

But here are these field notebooks, and hundreds of unedited pages on my hard drive. It was my habit to write daily. Over the last year, recovering from a brain injury has made it hard to write more than a few sentences at a time.

This morning I was looking at some of my pictures from my research in the Arctic last summer, and I was hit with a feeling of loss. Those photos and those notes should be a book by now, and perhaps several articles and book chapters, too. Instead, over the last year, as I have waited for my body and brain to heal, and as I struggled to do my teaching, I had no strength to write.

It feels funny to say that, but perhaps I am not alone in finding that a brain injury can be slow to heal and extremely tiring. I don't say that to get your sympathy. I am blessed with a very supportive community and an amazing wife who somehow has kept our life together and nursed me through my healing process. I'm fortunate. But if you've read this far, you might consider whether there are others around you who look like they're doing well physically but who might be nursing invisible wounds or who might be struggling to cope with invisible disabilities. This past year has given me a new perspective on that by making me aware of my own disabilities, most of which you won't notice if you see me at the gym or in one of my classrooms.

I might not be able to write another book yet, so for now, here's my plan: I'll write a little at a time. Thankfully, I've got my notes, sketches, and photos. I'll start with them.

If you're curious about how a professor of philosophy and classics does research and writing about nature - and how he works to recover from a serious brain injury - you might check out some of my recent publications. My book Downstream is the result of eight years of field research on the ecology of the Appalachians, with a focus on brook trout. On this blog you'll also find my recently published poem, "Sage Creek," which might give you a glimpse of my ancient philosophy class camping and stargazing in the Badlands. Or feel free to look at my photos on Instagram. Even when I can't teach in the field, I can still wander my garden with a hand lens and camera.

∞

Good Education Should Lead To Good Questions

"If we treat the contemplation of the best life as a luxury we cannot

afford, seemingly urgent matters will crowd out the truly important

ones."

[....]

"If the aim of education is to gain money and power, where can we turn for help in knowing what to do with that money and power? Only a disordered mind thinks that these are ends in themselves. Socrates offers us the cautionary tale of the athlete-physician Herodicus, who wins fame and money through his athletic prowess and medicine, then proceeds to spend all his wealth trying to preserve his youth. This is what we mean by a disordered mind. He has been trained in the STEM fields of his time, and his training gains him great wealth, but it leaves him foolish enough to spend it all on something he can never buy."

[....]

"If the aim of education is to gain money and power, where can we turn for help in knowing what to do with that money and power? Only a disordered mind thinks that these are ends in themselves. Socrates offers us the cautionary tale of the athlete-physician Herodicus, who wins fame and money through his athletic prowess and medicine, then proceeds to spend all his wealth trying to preserve his youth. This is what we mean by a disordered mind. He has been trained in the STEM fields of his time, and his training gains him great wealth, but it leaves him foolish enough to spend it all on something he can never buy."

From my latest article, co-authored with John Kaag, in The Chronicle of Higher Education. Read it all here.

∞

What Thucydides Can Teach Us About Imperial Overreach

My latest article, co-authored with John Kaag. Here's a sample:

"As we dwell in our golden, Athenian age of military and economic might, perhaps we should learn another lesson from the ancients as well. Aristotle tells us that a virtuous soul is not a soul without fear, but one that fears only the right things; and it is not moved by fear, because it tempers it with wisdom. In the end, the loss of virtue may be more dire than the loss of geopolitical prominence."You can read it all here.

∞

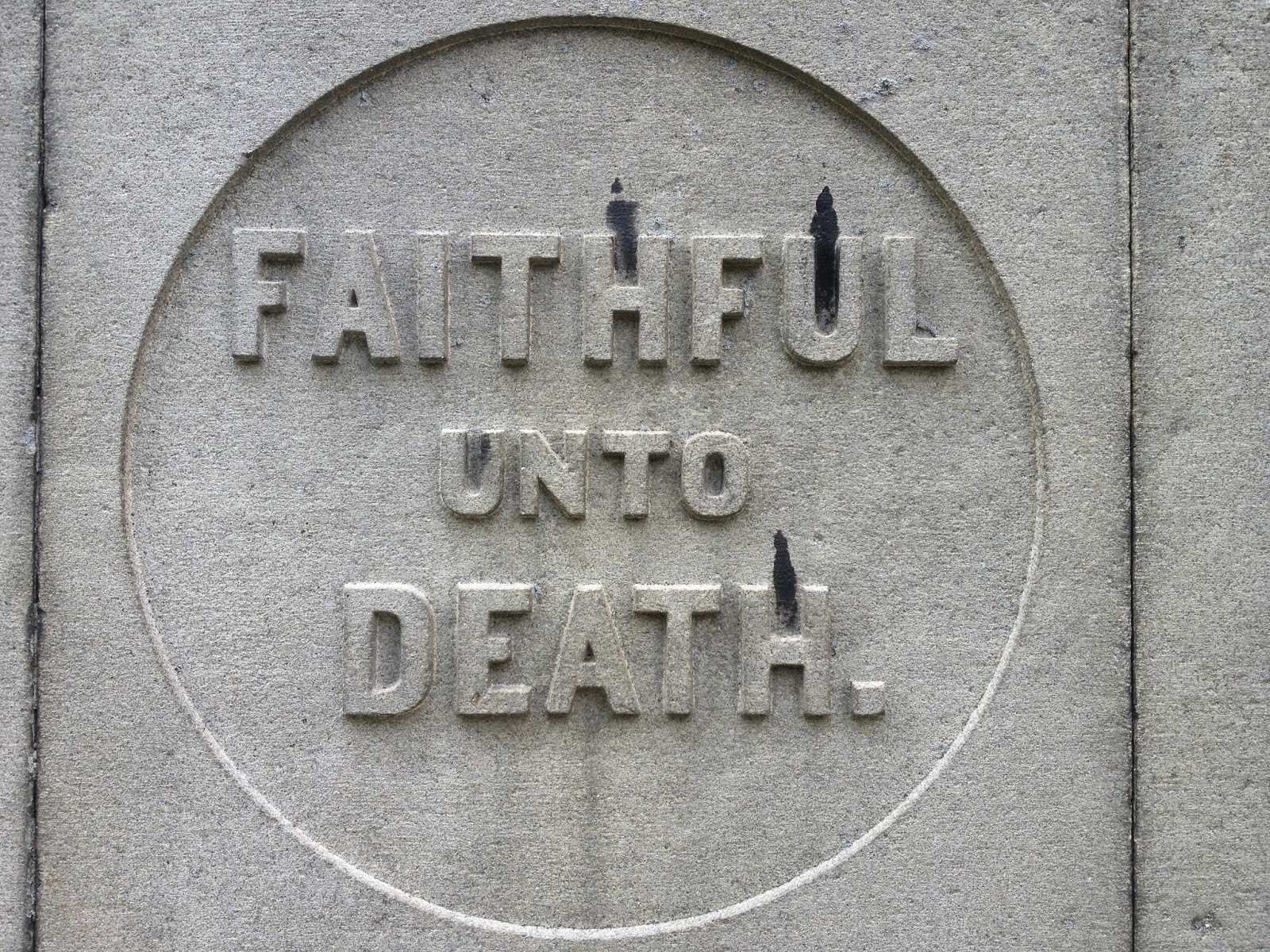

Who Are You Calling A "Hero"?

Most common uses of the word "hero" fall into one of two categories: we either use it to refer to someone ordinary who does something extraordinary - a passerby who rescues a child who has fallen into a canal, for instance - or to anyone who wears a uniform.

The problem with the first usage is that it makes heroism something accidental. The hero is in every way ordinary, but then they are faced with sudden unanticipated hardship and they overcome it. Little attention is paid to what led to the heroic act. It was an event thrust upon the hero, and nothing prepared the hero for this heroism. They just chose well in a tight situation. When we use the word this way we undervalue the character of the "hero," and ignore their discipline and virtues (or lack thereof).

The second usage has three problems: First, it's obviously mistaken, as events like Abu Ghraib and My Lai should make plain. Second, as with the first usage, it diminishes the long, hard work of those men and women who live heroically through self-discipline and the cultivation of courage and moral character. Third, this usage is almost always cynical, and politically motivated. It is usually the politician who says it, and usually for the benefit of the politician. It is a shibboleth of political life to "honor the troops" or "salute the men and women in uniform" in words -- and usually in words only. Real honor and real salutes come through much harder means, like supporting them financially, emotionally, and spiritually.

Aristotle (correctly) said you can't really judge someone's life as happy until they have lived it all. It's probably similar with calling someone a hero. Certainly we should stop making statues of people while they're still alive. It should probably be a rule of life that we shouldn't call anyone a hero without serious public debate leading to consensus. When you compare the process by which the Catholic church determines whether to call someone a saint to the process by which an American politician decides to call someone a hero, it's pretty plain which of the two processes is more rigorous and which is cynical and thoughtless. At least the church engages in research first.

Maybe we should stop using the word altogether, because there is another problem that comes with most uses of the word: naming someone a hero practically divinizes that person, making it much harder for us to think critically about his flaws. This ought to concern all of us, and especially the one called a hero, who is thereby even further distanced from our common life.

The problem with the first usage is that it makes heroism something accidental. The hero is in every way ordinary, but then they are faced with sudden unanticipated hardship and they overcome it. Little attention is paid to what led to the heroic act. It was an event thrust upon the hero, and nothing prepared the hero for this heroism. They just chose well in a tight situation. When we use the word this way we undervalue the character of the "hero," and ignore their discipline and virtues (or lack thereof).

The second usage has three problems: First, it's obviously mistaken, as events like Abu Ghraib and My Lai should make plain. Second, as with the first usage, it diminishes the long, hard work of those men and women who live heroically through self-discipline and the cultivation of courage and moral character. Third, this usage is almost always cynical, and politically motivated. It is usually the politician who says it, and usually for the benefit of the politician. It is a shibboleth of political life to "honor the troops" or "salute the men and women in uniform" in words -- and usually in words only. Real honor and real salutes come through much harder means, like supporting them financially, emotionally, and spiritually.

Aristotle (correctly) said you can't really judge someone's life as happy until they have lived it all. It's probably similar with calling someone a hero. Certainly we should stop making statues of people while they're still alive. It should probably be a rule of life that we shouldn't call anyone a hero without serious public debate leading to consensus. When you compare the process by which the Catholic church determines whether to call someone a saint to the process by which an American politician decides to call someone a hero, it's pretty plain which of the two processes is more rigorous and which is cynical and thoughtless. At least the church engages in research first.

Maybe we should stop using the word altogether, because there is another problem that comes with most uses of the word: naming someone a hero practically divinizes that person, making it much harder for us to think critically about his flaws. This ought to concern all of us, and especially the one called a hero, who is thereby even further distanced from our common life.

∞

College Athletics: Cui Bono?

This Strange Marriage of Athletics and Academics

This week I've been considering the place of sports on American university and college campuses. (See here and here for the other pieces I've written on this this week.)

If you grow up here, it doesn't seem at all strange, because it's simply how things are. But a little reflection suggests that the juxtaposition of academics and athletics is a little strange.

I say it is "a little" strange because throughout the ages thoughtful people have said that the two complement each other. Plato's Republic discusses the relationship between gymnastics for the body and philosophy for the mind, for instance. Of course, Plato, famous for his irony, is never wholly straightforward, and the target he is aiming at is probably something else, but the characters in his dialogue act as though bodily exercise and mental exercise are related.

Walking, Playing, and Thinking

One of Socrates' other students, Xenophon, wrote in his Cynegetica that the best education comes through learning to hunt, and that book-learning should only come after a boy has learned the art of coursing with hounds, and practiced it in the country. And there are many others who tell us that moving our bodies and learning go together: Maria Montessori reminds us that the work of children is play. Philosophers as diverse as Aristotle, Nietzsche, C.S. Lewis, Henry Thoreau and Charles S. Peirce tell us that walking and thinking are natural companions.

So the strangeness of the marriage of learning and playing is not the hypothesis that the body and the mind work both need exercise. The strangeness is the way we pursue - or, just as often, fail to pursue - that hypothesis. We are told that movement helps us think, and that playing team sports teaches us virtue. If all that is true, then why do we not encourage all students to play sports?

The Irony: We Do Not Practice As We Preach

Speaking of irony, consider this: What we claim and what we actually do are at odds with one another. We say sports are good for everyone, then we expect coaches to eliminate all but the best athletes from their instruction. Rather than advertising our schools as places where students can get an excellent physical education we expect our coaches to travel far and wide to recruit only the best athletes, i.e. those who need the least instruction and who are most likely to win competitions. It is fairly obvious that, rather than using athletics as a means of inculcating virtue and fostering better thinking, we use athletics to gain honor through victories.

And of course, this is obvious to us. We want to win games because winning is a form of advertising. For good or ill, we accept the fact that high school students will often choose our school in order to participate in the glory of competitions won. But we continue to give the other justifications for participation in athletics, perhaps because we perceive that it would be crass to come right out and say "Come to our college and bask in the glory won by others. It will thrill you, and it might help your job prospects," or "We hope that the victories of our athletes will help us to raise money from people who won't give unless we are winning games."

I don't want to be cynical about this. As I have suggested above and said directly in my previous posts, I'm in favor of athleticism. What troubles me about it is the way that certain college sports become increasingly professionalized. Why, after all, are student athletes considering unionizing? That's something employees do, not students.

Let Everyone Learn To Play

My conclusion is not to push for the elimination of college athletics, but for athletics to be brought more into line with the best reasons for preserving it. If playful exercise makes us better people and better students, then let's urge more students to play. Let's give less attention to inter-collegiate competition and more attention to teaching lifetime sports that will allow our alumni to enjoy the benefits of physical activity for the remainder of their lives. Let's teach poorer students to play golf so that when they enter the business world they aren't at a disadvantage when deals are made on the fairway. Let's teach everyone to swim. Let's take all our students on walks - serious walks, cross-country walks. Let's teach them what Thoreau calls the art of sauntering.

Playful activity takes many forms. We should resist the temptation to think of it as the pursuit of a ball. Swimming, hiking, rock climbing, Tai Chi, dance, yoga, and numerous other activities have the same moral and intellectual benefits as team sports. There should be as many opportunities for vigorous play as there are bodies.

Some of my friends have balked at this, understandably. Not all of us are athletic, or at least not all of us feel athletic. But I think a good deal of this is because many of us learned about athletics in a victory-oriented environment. That environment fosters a narrow and shallow view of the active human life. We may not all be quarterbacks, point guards, shortstops, or strikers, but all of us can be active within the limits of the bodies we have been given. If activity is good for us, then we should treat it as good for all of us. Play should not be limited to the activity of a few for the thrill of the inactive many. Play should be, as Peirce said, "a lively exercise of our powers," whatever those powers may be. And it should be a delight.

This week I've been considering the place of sports on American university and college campuses. (See here and here for the other pieces I've written on this this week.)

If you grow up here, it doesn't seem at all strange, because it's simply how things are. But a little reflection suggests that the juxtaposition of academics and athletics is a little strange.

I say it is "a little" strange because throughout the ages thoughtful people have said that the two complement each other. Plato's Republic discusses the relationship between gymnastics for the body and philosophy for the mind, for instance. Of course, Plato, famous for his irony, is never wholly straightforward, and the target he is aiming at is probably something else, but the characters in his dialogue act as though bodily exercise and mental exercise are related.

Walking, Playing, and Thinking

One of Socrates' other students, Xenophon, wrote in his Cynegetica that the best education comes through learning to hunt, and that book-learning should only come after a boy has learned the art of coursing with hounds, and practiced it in the country. And there are many others who tell us that moving our bodies and learning go together: Maria Montessori reminds us that the work of children is play. Philosophers as diverse as Aristotle, Nietzsche, C.S. Lewis, Henry Thoreau and Charles S. Peirce tell us that walking and thinking are natural companions.

So the strangeness of the marriage of learning and playing is not the hypothesis that the body and the mind work both need exercise. The strangeness is the way we pursue - or, just as often, fail to pursue - that hypothesis. We are told that movement helps us think, and that playing team sports teaches us virtue. If all that is true, then why do we not encourage all students to play sports?

The Irony: We Do Not Practice As We Preach

Speaking of irony, consider this: What we claim and what we actually do are at odds with one another. We say sports are good for everyone, then we expect coaches to eliminate all but the best athletes from their instruction. Rather than advertising our schools as places where students can get an excellent physical education we expect our coaches to travel far and wide to recruit only the best athletes, i.e. those who need the least instruction and who are most likely to win competitions. It is fairly obvious that, rather than using athletics as a means of inculcating virtue and fostering better thinking, we use athletics to gain honor through victories.

And of course, this is obvious to us. We want to win games because winning is a form of advertising. For good or ill, we accept the fact that high school students will often choose our school in order to participate in the glory of competitions won. But we continue to give the other justifications for participation in athletics, perhaps because we perceive that it would be crass to come right out and say "Come to our college and bask in the glory won by others. It will thrill you, and it might help your job prospects," or "We hope that the victories of our athletes will help us to raise money from people who won't give unless we are winning games."

I don't want to be cynical about this. As I have suggested above and said directly in my previous posts, I'm in favor of athleticism. What troubles me about it is the way that certain college sports become increasingly professionalized. Why, after all, are student athletes considering unionizing? That's something employees do, not students.

Let Everyone Learn To Play

My conclusion is not to push for the elimination of college athletics, but for athletics to be brought more into line with the best reasons for preserving it. If playful exercise makes us better people and better students, then let's urge more students to play. Let's give less attention to inter-collegiate competition and more attention to teaching lifetime sports that will allow our alumni to enjoy the benefits of physical activity for the remainder of their lives. Let's teach poorer students to play golf so that when they enter the business world they aren't at a disadvantage when deals are made on the fairway. Let's teach everyone to swim. Let's take all our students on walks - serious walks, cross-country walks. Let's teach them what Thoreau calls the art of sauntering.

Playful activity takes many forms. We should resist the temptation to think of it as the pursuit of a ball. Swimming, hiking, rock climbing, Tai Chi, dance, yoga, and numerous other activities have the same moral and intellectual benefits as team sports. There should be as many opportunities for vigorous play as there are bodies.

Some of my friends have balked at this, understandably. Not all of us are athletic, or at least not all of us feel athletic. But I think a good deal of this is because many of us learned about athletics in a victory-oriented environment. That environment fosters a narrow and shallow view of the active human life. We may not all be quarterbacks, point guards, shortstops, or strikers, but all of us can be active within the limits of the bodies we have been given. If activity is good for us, then we should treat it as good for all of us. Play should not be limited to the activity of a few for the thrill of the inactive many. Play should be, as Peirce said, "a lively exercise of our powers," whatever those powers may be. And it should be a delight.

∞

As September approaches, people keep asking me, "Are you ready to get back in the classroom?"

As early as middle school I knew I wanted to become a college professor, and I love my job. It is a delight to spend time with young people who are curious, after all.

Years ago, my friend Matt Dickerson pointed out to me that it's also my job to help those who are not curious to see why they should be. As it turns out, that work is usually delightful, too, a rewarding challenge.

So on the whole, I love my work.

But I admit I don't love classrooms, for several reasons:

First, no matter what decade, every classroom I've been in has exhibited an unhealthy tendency towards becoming cluttered with the latest technology, and most of that tech seems to take up a lot of space and to become the center of attention. I'm not opposed to technology in the classroom, not at all. But I'm opposed to letting it get in the way, as it does when the "Smart Cart" leaves me no room for my lecture notes, or when I can't seem to turn the ceiling-mounted projector on or off. I'm a fan of chalk, because chalk allows spontaneity, and it allows for much more than alphanumeric writing in neat rows. Sadly, concerns about chalk dust getting into computers is threatening to make chalkboards disappear from my classrooms. Alas. Chalk is an excellent technology, and if it vanishes, I will mourn its loss.

Second, classroom architecture is not some value-free, neutral design. Classroom architecture makes a big difference in how people teach, and how they learn:

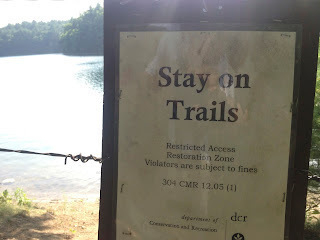

Which is why, as often as I can, I get my students out of the classroom. When we are reading Thoreau's Walking, we go for a walk. When I teach environmental philosophy, we often meet under the great tree in our campus quad, where I encourage students to daydream and to play with the grass, to look for worm-castings and owl pellets, feathers and seed-pods, invertebrates and fallen bits of bark. What good is it to gain the world of theoretical knowledge at the expense of knowledge gained through vital, haptic, bodily experience?

And this is why I am a preacher of the importance of study abroad. Not just travel, but serious, engaged, rigorous study in the classroom of life in another place. This is why I teach Classics in Greece every year, and why year after year I take students to Central America to study environmental philosophy and ecology.

More and more I've been trying to shift the learning focus in my classes from the classroom to the laboratory - where by "laboratory" I mean anywhere that allows students to learn with their whole person. I make my ancient philosophy students devote hours each semester to star-gazing, in part because this is what the ancients did, and in part because I don't want them to miss the stars. I want them to gaze in wonder at the firmament so that when they read Aristotle and Galileo they know that they've looked at what those great minds saw as well. We even occasionally take field trips to really dark places like the South Dakota Badlands so we can see the skies even better.

My environmental philosophy students must observe a square meter of earth for a semester, spending an hour at a time without a camera, drawing and writing about what they see, because it does not make sense to me to talk about the earth when you have not taken the time to sit upon it, to listen to it, to smell and taste it, and to see what other lives creep, and walk, and fly across it.

My friend Aage Jensen advocates the Norwegian philosophy of Friluftsliv, life and education outdoors. And when he organizes a conference on it, he eschews conference centers and holds the conference while walking through the mountains, or paddling a river. Because he believes that one should practice what one preaches, and that nature is always ready to teach.

To paraphrase the Stoic Musonius, teachers would do well to talk less and to take their students with them into the fields, because there they will learn far better and far more than in the lecture hall.

Teaching Outdoors

|

As early as middle school I knew I wanted to become a college professor, and I love my job. It is a delight to spend time with young people who are curious, after all.

Years ago, my friend Matt Dickerson pointed out to me that it's also my job to help those who are not curious to see why they should be. As it turns out, that work is usually delightful, too, a rewarding challenge.

So on the whole, I love my work.

But I admit I don't love classrooms, for several reasons:

First, no matter what decade, every classroom I've been in has exhibited an unhealthy tendency towards becoming cluttered with the latest technology, and most of that tech seems to take up a lot of space and to become the center of attention. I'm not opposed to technology in the classroom, not at all. But I'm opposed to letting it get in the way, as it does when the "Smart Cart" leaves me no room for my lecture notes, or when I can't seem to turn the ceiling-mounted projector on or off. I'm a fan of chalk, because chalk allows spontaneity, and it allows for much more than alphanumeric writing in neat rows. Sadly, concerns about chalk dust getting into computers is threatening to make chalkboards disappear from my classrooms. Alas. Chalk is an excellent technology, and if it vanishes, I will mourn its loss.

Second, classroom architecture is not some value-free, neutral design. Classroom architecture makes a big difference in how people teach, and how they learn:

|

| Step off the trails! Explore! An ironic sign at Walden Pond. |

And this is why I am a preacher of the importance of study abroad. Not just travel, but serious, engaged, rigorous study in the classroom of life in another place. This is why I teach Classics in Greece every year, and why year after year I take students to Central America to study environmental philosophy and ecology.

More and more I've been trying to shift the learning focus in my classes from the classroom to the laboratory - where by "laboratory" I mean anywhere that allows students to learn with their whole person. I make my ancient philosophy students devote hours each semester to star-gazing, in part because this is what the ancients did, and in part because I don't want them to miss the stars. I want them to gaze in wonder at the firmament so that when they read Aristotle and Galileo they know that they've looked at what those great minds saw as well. We even occasionally take field trips to really dark places like the South Dakota Badlands so we can see the skies even better.

My environmental philosophy students must observe a square meter of earth for a semester, spending an hour at a time without a camera, drawing and writing about what they see, because it does not make sense to me to talk about the earth when you have not taken the time to sit upon it, to listen to it, to smell and taste it, and to see what other lives creep, and walk, and fly across it.

My friend Aage Jensen advocates the Norwegian philosophy of Friluftsliv, life and education outdoors. And when he organizes a conference on it, he eschews conference centers and holds the conference while walking through the mountains, or paddling a river. Because he believes that one should practice what one preaches, and that nature is always ready to teach.

To paraphrase the Stoic Musonius, teachers would do well to talk less and to take their students with them into the fields, because there they will learn far better and far more than in the lecture hall.

|

| Nature is full of things worth seeing. |

∞

Back To Work

Restful Work

I've been on sabbatical for the last academic year, and it has been a gift.

I've done a lot of writing (I think I've averaged about 750 words a day, which may not sound like much, but it is) and a lot of reading (roughly a half a book a day for fifteen months) and a lot of traveling (visited five countries; had one writing fellowship on the west coast and one NEH study fellowship on the east coast; read and wrote at a writer's conference in Vermont; attended a handful of other conferences; and a whole lot more. I lived out of my suitcase for the first two months of this summer.)

In other words, my sabbatical hasn't been idle time. Quite the opposite.

But now I'm ready to get back to work. To the work I feel called to do, that is. All the work I've done for the last year has been aimed at a particular purpose: to make me a better teacher.

Those Who Can, Teach

No doubt you've heard it said that "those who can, do; those who can't, teach." Anyone who has tried to teach well knows exactly why that saying is false.

In one small way, it can sometimes be true: it may be that the teacher lacks the physical capability to perform the tasks she teaches. But if she teaches them, she must understand them at least as well as those who perform them. Good athletic coaches illustrate this idea well: a man may be a brilliant football coach well after he's too old to survive being tackled; a woman may understand her sport far better after her body will no longer allow her to participate in it.

But in each case it is obvious that the teacher has some mastery that is greater than the bodily capacity to do the activity.

To paraphrase Aristotle: the craftsman knows something, but the one who teaches the craftsman must know even more. My sabbatical has been a chance to deepen precisely the kind of knowledge I need to be a good teacher.

Be The Change You Want To See In Your Students

I can't speak for all teachers, but I find that it is not enough to know only as much as I plan to teach. When I teach a course in philosophy, philology, theology, ecology, or history I must become a student of that discipline myself.

This is one of the reasons why humanities professors are always reading and writing. It is not enough to tell the students what we know. As Plutarch put it, "The mind is not a vessel to be filled but a fire to be kindled." My job is not to impart information; my job is to make students. My job is the work of conversion, of helping people become what they were not, of facilitating the habit of learning throughout one's whole life.

To put it negatively, my job is to avoid being a hypocrite. More positively, my job is to be an example of the kind of change I wish to see in my students. And this is why sabbaticals are so important. They are not a reward for service, a respite from the work of teaching. They are a chance to immerse oneself in the life of the student again, to strengthen the scholarly habits. Sabbaticals make better teachers.

Looking Forward To My Real Work

Recently I was having a drink with some other professors in my field as we sat on a hotel rooftop in Athens. Several of them described the tricks they've come up with to minimize grading and teaching, so that they can spend more time on their "real work." This "real work" turned out to be their research.

Recently I was having a drink with some other professors in my field as we sat on a hotel rooftop in Athens. Several of them described the tricks they've come up with to minimize grading and teaching, so that they can spend more time on their "real work." This "real work" turned out to be their research.

Kvetching in bars is a popular pastime for many professions, so I won't hold those words against them. And I can't claim to know what the difficulties of their lives are like, nor how hard it is for them to manage the stresses of the job market (neither of them has a stable position). And both of them may in fact be excellent researchers who are producing books and articles the world needs.

But it made me sad to hear that things have so fallen out for them that they have come to regard teaching as an impediment to their real work. I love teaching, and I'm grateful for the privilege of spending time with books and pens and bright young minds. I love the way the books and pens become tools for working out our life together.

Some of my friends have been ribbing me about having to go back to work after a yearlong sabbatical. I'm sure it will present some challenges, and I'll have less control of my schedule. But honestly, I've missed the classroom. This year has been like time in the shop, taking apart the engine and replacing worn parts, topping off the fluids, recharging the battery. As the sabbatical comes to a end, I find I'm eager to rev the engine and step on the pedal. I'm looking forward to seeing my older students, and to meeting the new ones. I'm looking forward to engaging in the lofty work I've been called to, of helping young people think in ways they had not yet imagined. I'm looking forward to seeing their eyes light up as they read Plato and Kant and Emerson, to hearing their challenges, to seeing what happens when they, too, step on the pedal and squeal the tires. I can't wait to get back to work.

*****

If you're curious: The Plutarch quote, above, comes from near the end of his "On Listening To Lectures." This is my rough translation, which I think comes pretty close to what he says.

I've been on sabbatical for the last academic year, and it has been a gift.

I've done a lot of writing (I think I've averaged about 750 words a day, which may not sound like much, but it is) and a lot of reading (roughly a half a book a day for fifteen months) and a lot of traveling (visited five countries; had one writing fellowship on the west coast and one NEH study fellowship on the east coast; read and wrote at a writer's conference in Vermont; attended a handful of other conferences; and a whole lot more. I lived out of my suitcase for the first two months of this summer.)

In other words, my sabbatical hasn't been idle time. Quite the opposite.

But now I'm ready to get back to work. To the work I feel called to do, that is. All the work I've done for the last year has been aimed at a particular purpose: to make me a better teacher.

Those Who Can, Teach

No doubt you've heard it said that "those who can, do; those who can't, teach." Anyone who has tried to teach well knows exactly why that saying is false.

In one small way, it can sometimes be true: it may be that the teacher lacks the physical capability to perform the tasks she teaches. But if she teaches them, she must understand them at least as well as those who perform them. Good athletic coaches illustrate this idea well: a man may be a brilliant football coach well after he's too old to survive being tackled; a woman may understand her sport far better after her body will no longer allow her to participate in it.

But in each case it is obvious that the teacher has some mastery that is greater than the bodily capacity to do the activity.

To paraphrase Aristotle: the craftsman knows something, but the one who teaches the craftsman must know even more. My sabbatical has been a chance to deepen precisely the kind of knowledge I need to be a good teacher.

Be The Change You Want To See In Your Students

I can't speak for all teachers, but I find that it is not enough to know only as much as I plan to teach. When I teach a course in philosophy, philology, theology, ecology, or history I must become a student of that discipline myself.

This is one of the reasons why humanities professors are always reading and writing. It is not enough to tell the students what we know. As Plutarch put it, "The mind is not a vessel to be filled but a fire to be kindled." My job is not to impart information; my job is to make students. My job is the work of conversion, of helping people become what they were not, of facilitating the habit of learning throughout one's whole life.

To put it negatively, my job is to avoid being a hypocrite. More positively, my job is to be an example of the kind of change I wish to see in my students. And this is why sabbaticals are so important. They are not a reward for service, a respite from the work of teaching. They are a chance to immerse oneself in the life of the student again, to strengthen the scholarly habits. Sabbaticals make better teachers.

Looking Forward To My Real Work

Recently I was having a drink with some other professors in my field as we sat on a hotel rooftop in Athens. Several of them described the tricks they've come up with to minimize grading and teaching, so that they can spend more time on their "real work." This "real work" turned out to be their research.

Recently I was having a drink with some other professors in my field as we sat on a hotel rooftop in Athens. Several of them described the tricks they've come up with to minimize grading and teaching, so that they can spend more time on their "real work." This "real work" turned out to be their research.Kvetching in bars is a popular pastime for many professions, so I won't hold those words against them. And I can't claim to know what the difficulties of their lives are like, nor how hard it is for them to manage the stresses of the job market (neither of them has a stable position). And both of them may in fact be excellent researchers who are producing books and articles the world needs.

But it made me sad to hear that things have so fallen out for them that they have come to regard teaching as an impediment to their real work. I love teaching, and I'm grateful for the privilege of spending time with books and pens and bright young minds. I love the way the books and pens become tools for working out our life together.

Some of my friends have been ribbing me about having to go back to work after a yearlong sabbatical. I'm sure it will present some challenges, and I'll have less control of my schedule. But honestly, I've missed the classroom. This year has been like time in the shop, taking apart the engine and replacing worn parts, topping off the fluids, recharging the battery. As the sabbatical comes to a end, I find I'm eager to rev the engine and step on the pedal. I'm looking forward to seeing my older students, and to meeting the new ones. I'm looking forward to engaging in the lofty work I've been called to, of helping young people think in ways they had not yet imagined. I'm looking forward to seeing their eyes light up as they read Plato and Kant and Emerson, to hearing their challenges, to seeing what happens when they, too, step on the pedal and squeal the tires. I can't wait to get back to work.

*****

If you're curious: The Plutarch quote, above, comes from near the end of his "On Listening To Lectures." This is my rough translation, which I think comes pretty close to what he says.

∞

Armed in Anxiety

My article on guns, fear, and virtue ethics, now accessible at The Chronicle of Higher Education:

What do guns do for us? Many opponents of new gun legislation argue that they make us safer. Proponents of gun control hope to promote public safety by keeping guns out of the hands of bent young men who worship projectile power and senseless death. Most of our public-policy debates about guns have focused on safety, but in my opinion, not enough has been said about whether guns make us sound.Read the rest here.

Our word "safe" has roots in the Latin word salvus, which means not just "secure from harm" but "whole, well, and thriving"—that is to say, sound. This is one of philosophy's oldest concerns, to examine and foster this kind of sound, flourishing human life. This question is at the heart of Aristotle's ethics, for example. The opening lines of his Nicomachean Ethics declare that it is possible to regard life as having a kind of excellence, a sense of human flourishing and wholeness to which all of our sciences contribute. As Aristotle puts it, failure to reflect on this will make us like people who shoot without considering their target. (Yes, he really says that.)....

∞

Unwritten

Some of my favorite passages in any texts are about texts

that cannot be read.

Take the story of a man writing on the ground with his finger thousands of years ago. We do not know what he wrote, we only know that he wrote.

The story is in John’s Gospel, and the scene was this: some men brought Jesus a woman whom, they said, they had caught in adultery.

The passage does not occur in the oldest manuscripts, but it appears in some that are old enough that this pericope has been included in the canonical text.

And it is a delicious passage.

For one thing, it reminds us that even if we have the whole of the Scriptures, we still do not know everything Jesus said or wrote. Or thought.

It is one of the blank spaces in which commentary has not yet been written. Which makes it an invitation to imagine – not to devise religious rules on the basis of conjecture, but to engage in the work of strenuous wonder: what might he have written?

I came up with an answer once, and Merold Westphal put it even better in his book Suspicion and Faith. I won’t spoil it for you by telling you now.