atheism

∞

Charles Peirce on Transcendentalism, and the Common Good

From one of Charles S. Peirce's college writings, dated 1859. At the time he was a student at Harvard College.

It's a short paragraph, but it offers considerable insight into the development of Peirce's thought, and it is full of suggestion for our own time.

His claim that a scholar must devote herself to one area only must be taken in the context of Peirce's own studies. Peirce was himself a polymath who wrote on logic, metaphysics, physics, geometry, ancient philology, semiotics, mathematics, and chemistry, among other disciplines.

What he says about learning here is relevant for the ancient tradition of publishing the results of inquiry, and for the contemporary practice of patenting all discoveries. Nature is not a gift from God to the individual researcher. Peirce's invocation of God here calls to mind what he says elsewhere about both God and research. (For more on how Peirce regarded the relationship between God and science, see my chapter in Torkild Thellefsen's collection of essays on Peirce, Peirce in His Own Words.) The idea of God provides an ideal for the researcher, a reason to expect natural research to be productive of knowledge and a reason to believe in the possible unity of knowledge.

(This helps us to understand Peirce's peculiar interest in religion, by the way: he thought religion both indispensable and unavoidable, claiming that even most atheists believe in God, though most of them are unaware of their own belief, because they have explicitly rejected a particular kind of theism while maintaining a steadfast belief in some of the consequences of theism. At the same time, Peirce was opposed to all infallible claims, to the exclusionary nature of creeds, and to what he considered to be the illogic of seminary-training.)

Peirce grew up, as he puts it, "in the neighborhood of Cambridge," i.e. near the home of American Transcendentalism. He says of his family that "one of my earliest recollections is hearing Emerson [giving] his address on 'Nature'.... So we were within hearing of the Transcendentalists, though not among them. I remember when I was a child going upon an hour's railway journey with Margaret Fuller, who had with her a book called the Imp [3] in the Bottle." (MS 1606) His critiques of Transcendentalism have to be read in this context: he was raised among them, with Emerson in his childhood living room and with Emerson's writings being discussed in his school.

Emerson's insight is that nature does speak to those who have ears to hear. His error is in mistaking the relationship of one person to another. Emerson's genius is in perceiving the Over-soul, and his error is in then presupposing the radical individuality of the genius. Peirce does not doubt that there are geniuses. As a chemist, Peirce knew the importance of research and he knew the real possibility of achieving previously unknown insight. Peirce believed, however, that the insight of the genius, or of any serious researcher for that matter, belongs to the whole community of inquiry.

Peirce, who made his living on research, believed that the researcher deserved to earn her living from her work, and he was sometimes frustrated by the chemical companies who took his ideas and patented them, then refused to pay him for them. His ideal - one that is admittedly very difficult to realize - was that all research would be made freely available to the whole community of inquiry. So while the researcher is worth her wages, no one deserves the privilege of hoarding knowledge for private gain. We are all in this together.

******

[1] I'm not sure which Everett Peirce alludes to, but possibly to Edward Everett, who was Emerson's teacher; or Alexander H. Everett, with whom Emerson corresponded.

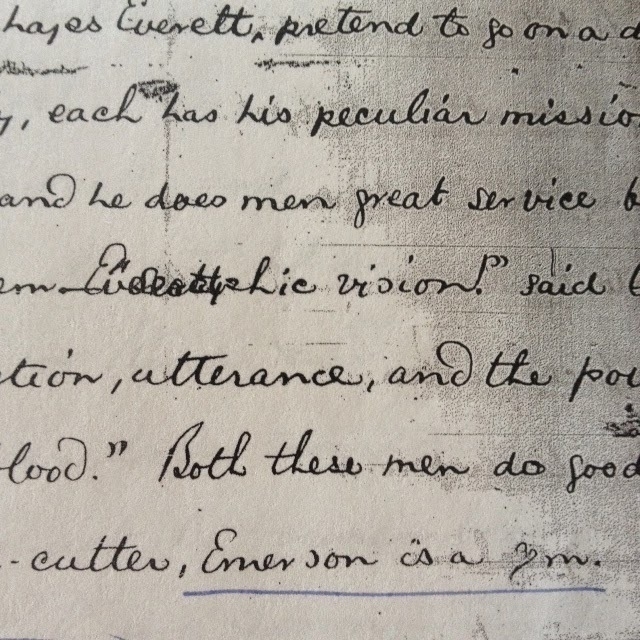

[2] The word on Peirce's manuscript is difficult to read. I have transcribed this from a photocopy of one of Peirce's original handwritten pages. The word might be "ecstatic" but I don't think it is. See the image above. [Update: Chris Paone wrote to me with the suggestion that the obscured word might be "seraphic." This is a better guess than any I've come up with so far, so until someone has a better idea, I'll take Chris to be right.]

[3] This word is also unclear, and might read "Ink." If you're curious about this, or if you've got some insight about this, write to me in the comments below; I've spent some time trying to figure out what book Fuller had with her, so far with only a small amount of success.

With each of these footnotes, I welcome your feedback and corrections in the footnotes below. Peirce wrote that the work of the researcher is never a solitary affair, but always the work of a community of inquiry, after all.

"The devotion to fair learning is not of this rabid kind, but it is more selfish. Antiquity has not accumulated its treasures for me; God has not made nature for me: if I wish to belong to the community of wise men, my time is not my own; my mind is not my own; in this age division of labor is indispensable; one man must study one thing; develope one part of his intellect and, if necessary, let the rest go, for the good of humanity. Emerson, and perhaps Everett [1], pretend to go on a different principle; but really, each has his peculiar mission. Emerson is the man-child and he does men great service by just opening himself to them. "Seraphic [2] vision!" said Carlyle. Everett possesses "action, utterance, and the power of speech to stir men's blood." Both these men do good esthetically. Everett is a gem-cutter, Emerson is a gem." (MS 1633)

|

| A section of MS 1633, dated 1859 |

It's a short paragraph, but it offers considerable insight into the development of Peirce's thought, and it is full of suggestion for our own time.

His claim that a scholar must devote herself to one area only must be taken in the context of Peirce's own studies. Peirce was himself a polymath who wrote on logic, metaphysics, physics, geometry, ancient philology, semiotics, mathematics, and chemistry, among other disciplines.

What he says about learning here is relevant for the ancient tradition of publishing the results of inquiry, and for the contemporary practice of patenting all discoveries. Nature is not a gift from God to the individual researcher. Peirce's invocation of God here calls to mind what he says elsewhere about both God and research. (For more on how Peirce regarded the relationship between God and science, see my chapter in Torkild Thellefsen's collection of essays on Peirce, Peirce in His Own Words.) The idea of God provides an ideal for the researcher, a reason to expect natural research to be productive of knowledge and a reason to believe in the possible unity of knowledge.

(This helps us to understand Peirce's peculiar interest in religion, by the way: he thought religion both indispensable and unavoidable, claiming that even most atheists believe in God, though most of them are unaware of their own belief, because they have explicitly rejected a particular kind of theism while maintaining a steadfast belief in some of the consequences of theism. At the same time, Peirce was opposed to all infallible claims, to the exclusionary nature of creeds, and to what he considered to be the illogic of seminary-training.)

Peirce grew up, as he puts it, "in the neighborhood of Cambridge," i.e. near the home of American Transcendentalism. He says of his family that "one of my earliest recollections is hearing Emerson [giving] his address on 'Nature'.... So we were within hearing of the Transcendentalists, though not among them. I remember when I was a child going upon an hour's railway journey with Margaret Fuller, who had with her a book called the Imp [3] in the Bottle." (MS 1606) His critiques of Transcendentalism have to be read in this context: he was raised among them, with Emerson in his childhood living room and with Emerson's writings being discussed in his school.

Emerson's insight is that nature does speak to those who have ears to hear. His error is in mistaking the relationship of one person to another. Emerson's genius is in perceiving the Over-soul, and his error is in then presupposing the radical individuality of the genius. Peirce does not doubt that there are geniuses. As a chemist, Peirce knew the importance of research and he knew the real possibility of achieving previously unknown insight. Peirce believed, however, that the insight of the genius, or of any serious researcher for that matter, belongs to the whole community of inquiry.

Peirce, who made his living on research, believed that the researcher deserved to earn her living from her work, and he was sometimes frustrated by the chemical companies who took his ideas and patented them, then refused to pay him for them. His ideal - one that is admittedly very difficult to realize - was that all research would be made freely available to the whole community of inquiry. So while the researcher is worth her wages, no one deserves the privilege of hoarding knowledge for private gain. We are all in this together.

******

[1] I'm not sure which Everett Peirce alludes to, but possibly to Edward Everett, who was Emerson's teacher; or Alexander H. Everett, with whom Emerson corresponded.

[2] The word on Peirce's manuscript is difficult to read. I have transcribed this from a photocopy of one of Peirce's original handwritten pages. The word might be "ecstatic" but I don't think it is. See the image above. [Update: Chris Paone wrote to me with the suggestion that the obscured word might be "seraphic." This is a better guess than any I've come up with so far, so until someone has a better idea, I'll take Chris to be right.]

[3] This word is also unclear, and might read "Ink." If you're curious about this, or if you've got some insight about this, write to me in the comments below; I've spent some time trying to figure out what book Fuller had with her, so far with only a small amount of success.

With each of these footnotes, I welcome your feedback and corrections in the footnotes below. Peirce wrote that the work of the researcher is never a solitary affair, but always the work of a community of inquiry, after all.

∞

Pragmatic Stoic Theology

In preparing a class on later Stoicism, I came across a passage from Cicero's De Natura Deorum, or On The Nature Of The Gods. Cicero himself is not one to take sides, but he attempts to practice that virtue of presenting the views of others as fairly as he can. As part of this practice, Cicero attributes a god-argument to the Stoic Chrysippus in Book 2, section 16 (Latin text here) of his De Natura Deorum.

Chrysippus' god-argument is not, strictly speaking, a proof of the existence of a god. It is rather an appeal to what he thinks is common sense, and to the consequences of not believing.

The first part, the appeal to common sense, goes something like this:

The second part makes a case that at least invites us to be cautious about dismissing it too readily. It goes like this:

But the most helpful part, I think, is (4), which stands as an invitation to consider who we are as we face the cosmos. We think of ourselves as natural, but we also think of ourselves as standing somehow apart from nature.

So it may be that there is nothing in the cosmos wiser or more clever than we are. We should be honest about this and acknowledge the real possibility that this is the case.

But Chrysippus invites us also to consider the consequences of that belief, since it could be taken as license to act as we will. The danger, as he sees it, is that we might become the sort of people who worship ourselves. This is dangerous in part because it impedes growth; we become like what we worship, and if we worship only ourselves, then we become our own best ideal. I will speak for myself when I say that I, at least, am a cramped and stingy ideal.

Many of the Stoics are content to name nature as god; what matters is that there always be something worth our attention and admiration. I'm reminded of the wise words of David Foster Wallace, who said that

Wallace comes pretty close to Chrysippus. Neither is trying to convert you to a religion, neither is trying to set the rules for your life, but both are reporting on what they have seen when they have ventured in the direction of denying all the gods: off in that direction, they found they could escape all the gods except the god they then found that they forced themselves to become.

Which, to paraphrase Wallace, is a good reason for choosing to posit some god which, if it existed, would be worth your worship. And then, maybe, to test it by trying to worship it as though it were really there.

Chrysippus' god-argument is not, strictly speaking, a proof of the existence of a god. It is rather an appeal to what he thinks is common sense, and to the consequences of not believing.

The first part, the appeal to common sense, goes something like this:

1) If there is anything in nature that we can't have made then something greater than us made it;

2) That something is what we call a god.Of course, he is assuming that everything that exists must exist because it was made, and that it was made designedly by a single cause. We could object that natural arrangements might have more than one lesser natural cause; or we could contest the whole notion of greater and lesser and dismiss this part of his argument fairly easily.

The second part makes a case that at least invites us to be cautious about dismissing it too readily. It goes like this:

3) Unless there is divine power, human reason is the greatest thing we know of and can possess;

4) So if there are no gods, then we are the greatest beings in the cosmos. In which case, we are the gods.Of course there might be other things we don't know of that are more powerful than we are; or we might (wisely) regard nature as more powerful than we are.

But the most helpful part, I think, is (4), which stands as an invitation to consider who we are as we face the cosmos. We think of ourselves as natural, but we also think of ourselves as standing somehow apart from nature.

So it may be that there is nothing in the cosmos wiser or more clever than we are. We should be honest about this and acknowledge the real possibility that this is the case.

But Chrysippus invites us also to consider the consequences of that belief, since it could be taken as license to act as we will. The danger, as he sees it, is that we might become the sort of people who worship ourselves. This is dangerous in part because it impedes growth; we become like what we worship, and if we worship only ourselves, then we become our own best ideal. I will speak for myself when I say that I, at least, am a cramped and stingy ideal.

Many of the Stoics are content to name nature as god; what matters is that there always be something worth our attention and admiration. I'm reminded of the wise words of David Foster Wallace, who said that

There is no such thing as not worshipping. Everybody worships. The only choice we get is what to worship. And an outstanding reason for choosing some sort of god or spiritual-type thing to worship - be it JC or Allah, be it Yahweh or the Wiccan mother-goddess or the Four Noble Truths or some infrangible set of ethical principles - is that pretty much anything else you worship will eat you alive.You can read the rest of his brief, insightful talk here (or by searching for "This Is Water.")

Wallace comes pretty close to Chrysippus. Neither is trying to convert you to a religion, neither is trying to set the rules for your life, but both are reporting on what they have seen when they have ventured in the direction of denying all the gods: off in that direction, they found they could escape all the gods except the god they then found that they forced themselves to become.

Which, to paraphrase Wallace, is a good reason for choosing to posit some god which, if it existed, would be worth your worship. And then, maybe, to test it by trying to worship it as though it were really there.

∞

Proofs of God's Existence

Every time we encounter a proof of God's existence or non-existence, we should use it as an opportunity to ask: why is this proof being offered?

Too often I have seen Anselm's "ontological" argument abstracted from its context, as though the fact that his Proslogion begins with a prayer were inconsequential to the argument; or Descartes' proofs abstracted from his Meditations, as though it were not important that "God" serves an instrumental purpose for Descartes, allowing for the re-establishment of the world after he doubts its existence.

Anselm already believes when he writes his argument. He has arrived at his belief in some way other than argumentation, and there is no shame in that. Most of us arrive at most of our beliefs in less-than-purely-rational ways, and as William James has argued, we have the right to do so. It looks to me like Anselm is writing not in order to defeat all atheism (though that may be one of his aims) but in order to see if his faith and his understanding can be in agreement with one another.

Descartes might believe or he might not; I don't know how I could know. God matters in his Meditations because God offers an "Archimedean point," a fulcrum on which to rest the lever of reason, allowing Descartes to lift the world anew from the ruins of doubt. Whether or not Descartes believes in God's existence, God is useful to Descartes.

My point is that it is mistaken to assume that arguments about God - for or against God - are detached and detachable from other concerns, and when we neglect those concerns we might just be missing the most important aspect of those arguments, namely the human aspect. When we argue about God, we are usually also arguing about something else.

Too often I have seen Anselm's "ontological" argument abstracted from its context, as though the fact that his Proslogion begins with a prayer were inconsequential to the argument; or Descartes' proofs abstracted from his Meditations, as though it were not important that "God" serves an instrumental purpose for Descartes, allowing for the re-establishment of the world after he doubts its existence.

Anselm already believes when he writes his argument. He has arrived at his belief in some way other than argumentation, and there is no shame in that. Most of us arrive at most of our beliefs in less-than-purely-rational ways, and as William James has argued, we have the right to do so. It looks to me like Anselm is writing not in order to defeat all atheism (though that may be one of his aims) but in order to see if his faith and his understanding can be in agreement with one another.

Descartes might believe or he might not; I don't know how I could know. God matters in his Meditations because God offers an "Archimedean point," a fulcrum on which to rest the lever of reason, allowing Descartes to lift the world anew from the ruins of doubt. Whether or not Descartes believes in God's existence, God is useful to Descartes.

My point is that it is mistaken to assume that arguments about God - for or against God - are detached and detachable from other concerns, and when we neglect those concerns we might just be missing the most important aspect of those arguments, namely the human aspect. When we argue about God, we are usually also arguing about something else.