Bio-Itzá

- Plantas medicinales and Sustainable Agriculture: They are trying to teach their community the uses of the rainforest plants, and especially the medicinal uses of those plants, before that knowledge is lost. Along the way, they're trying to promote sustainable agriculture in a place that is being ravaged by slash-and-burn corn farms. These farms are only productive for 2-3 years on the fragile and thin rainforest soil of the Petén region, after which they are depleted. The Mayans used a system of crop rotation and of letting land lie fallow as a sustainable means of recharging the forest soils.

- Reserva Bio-Itzá: They are preserving one of the largest pieces of unbroken rainforest in the Americas, mostly without government or NGO support. While we were walking on one of the trails with two of their rangers (they have three) one of them stopped and got an anxious look in his eye. He held up a hand for us all to be silent. Very faintly in the distance, we heard it: a chainsaw. The director of the reserve, who was with us, gravely sent off the other ranger to look into it. "Sólo mirar, ¡nada más!" he said: just look, but don't do anything else. The rangers don't carry any weapons and they cannot afford to carry powerful radios or telephones. So they walk the perimeter trying to intercept people who are hunting endangered animals or cutting down ancient trees. When they find those people, they use the most powerful tool they have: they talk with the poachers and try to teach them about the forest they are trying to preserve. When the poachers have automatic weapons, this is a very risky business. These intrepid rangers consider it worth their while. Visit the reserve if you are able - it's an amazing education in itself, and the largely unexcavated Mayan ruins there are well worth seeing.

- Asuntos Sociales: They provide funding for rural students to stay in school, and are working on a number of other projects to try to improve the well-being of their community.

- Lenguas Mayas: One of their earliest movements was an attempt to preserve the Mayan languages of their region: Itzaj, Kek'chi, Mopan, and a handful of others. One reason to do this is that the names of the plants and animals in those languages are not just names but stories. Another reason is that the languages used to bind them together as a community. Unfortunately, they lost a generation that was castigated and fined for speaking in Mayan languages. On the positive side, there is now an institute in San José that is dedicated to preserving and teaching these languages.

∞

On Telling Stories

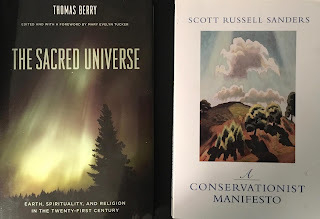

Posted for your consideration; words from two authors whose writing I find helpful, followed by a little commentary from me.

“Knowing on some intuitive level that we humans are guided by story, he ultimately called for the telling of the universe story. He felt that it was only in such a comprehensive scale that we could situate ourselves fully. His great desire was to see where we have come from and where we are going amid ecological destruction and social ferment. It was certainly an innovative idea, to announce the need for a new story that integrated the scientific understanding of evolution with its significance for humans. This is what he found so appealing in Teilhard’s seminal work."

“I’m one who dwells outside the camp of literary theory—so far outside that I can’t pretend to know much of what goes on there. I know scarcely more about deconstruction or postmodernism, say, than bumblebees and hummingbirds know about engineering. I don’t mean to brag of my ignorance nor to apologize for it, but only to explain why I’m not equipped to engage in debates about literary theory. What I can do is express my own faith in storytelling as a way of seeking the truth. And I can say why I believe we’ll continue to live by stories—grand myths about the whole of things as well as humble tales about the commonplace—as long as we have breath.”

A few years ago my wife and I, along with another family at our university, established a scholarship for Native American and First Nations students who wish to study to become storytellers. (Feel free to add to it by giving here if you are so inclined.)

Some people have since asked us why we did not invest our money in something more practical like helping individual students get into business or medical school. After all, that's where the money is, and higher income can correspond to greater independence and greater influence.

We see their point, but we both have committed ourselves to what might be considered storytelling disciplines because we think that stories shape lives and communities. A free society depends on good investigative journalists, good attorneys, and good public schools. A thriving society depends as well on good art and literature. And while religion has its downsides, it also has very strong upsides, and communities draw great benefit from healthy faith communities that remind us of our values, that give us places to congregate, to engage in commentary and contemplation, to welcome new life, to sustain commitments, to help us to mourn.

We often talk about the importance of STEM disciplines and healthcare, but I think we would do well to pay a little more attention to the way that good storytelling shapes healthcare (and the way bad storytelling makes us doubt good health practices like vaccination, for instance.)

I am persuaded that stories shape communities. They take what we have received from the past and transform and transmit it. If I am right, then I am prudent to invest in good storytelling. In the case of Native American and First Nations communities, I know just enough to know that there's a lot I don't know. And I'd like to know more.

I've been working with Bio-Itzá, a small Maya Itzá environmental group in Guatemala for the last decade, and I am constantly learning from the stories of their few surviving elders who grew up hearing the Itzá language spoken. The preservation of those words and stories means not just the preservation of a few tall tales, but the preservation of everything that is encoded and deeply rooted in those stories. The stories are cultural and ecological palimpsests, and when the Itzá elders tell them, they are passing on far more than mere words.

So my wife and I are committed to helping others to tell their stories. Because "we are guided by story," and "storytelling [is] a way of seeking the truth," and "we'll continue to live by stories."

“Knowing on some intuitive level that we humans are guided by story, he ultimately called for the telling of the universe story. He felt that it was only in such a comprehensive scale that we could situate ourselves fully. His great desire was to see where we have come from and where we are going amid ecological destruction and social ferment. It was certainly an innovative idea, to announce the need for a new story that integrated the scientific understanding of evolution with its significance for humans. This is what he found so appealing in Teilhard’s seminal work."

-- Mary Evelyn Tucker, in her preface to Thomas Berry’s The Sacred Universe. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009) (emphasis is mine)

“I’m one who dwells outside the camp of literary theory—so far outside that I can’t pretend to know much of what goes on there. I know scarcely more about deconstruction or postmodernism, say, than bumblebees and hummingbirds know about engineering. I don’t mean to brag of my ignorance nor to apologize for it, but only to explain why I’m not equipped to engage in debates about literary theory. What I can do is express my own faith in storytelling as a way of seeking the truth. And I can say why I believe we’ll continue to live by stories—grand myths about the whole of things as well as humble tales about the commonplace—as long as we have breath.”

-- Scott Russell Sanders, A Conservationist Manifesto. (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2009) (emphasis is mine)

*****

A few years ago my wife and I, along with another family at our university, established a scholarship for Native American and First Nations students who wish to study to become storytellers. (Feel free to add to it by giving here if you are so inclined.)

Some people have since asked us why we did not invest our money in something more practical like helping individual students get into business or medical school. After all, that's where the money is, and higher income can correspond to greater independence and greater influence.

We see their point, but we both have committed ourselves to what might be considered storytelling disciplines because we think that stories shape lives and communities. A free society depends on good investigative journalists, good attorneys, and good public schools. A thriving society depends as well on good art and literature. And while religion has its downsides, it also has very strong upsides, and communities draw great benefit from healthy faith communities that remind us of our values, that give us places to congregate, to engage in commentary and contemplation, to welcome new life, to sustain commitments, to help us to mourn.

We often talk about the importance of STEM disciplines and healthcare, but I think we would do well to pay a little more attention to the way that good storytelling shapes healthcare (and the way bad storytelling makes us doubt good health practices like vaccination, for instance.)

I am persuaded that stories shape communities. They take what we have received from the past and transform and transmit it. If I am right, then I am prudent to invest in good storytelling. In the case of Native American and First Nations communities, I know just enough to know that there's a lot I don't know. And I'd like to know more.

I've been working with Bio-Itzá, a small Maya Itzá environmental group in Guatemala for the last decade, and I am constantly learning from the stories of their few surviving elders who grew up hearing the Itzá language spoken. The preservation of those words and stories means not just the preservation of a few tall tales, but the preservation of everything that is encoded and deeply rooted in those stories. The stories are cultural and ecological palimpsests, and when the Itzá elders tell them, they are passing on far more than mere words.

So my wife and I are committed to helping others to tell their stories. Because "we are guided by story," and "storytelling [is] a way of seeking the truth," and "we'll continue to live by stories."

∞

Teaching Tropical Ecology in Belize and Guatemala

Two out of every three January terms my colleague Craig Spencer and I teach a course on tropical ecology in Central America. Right now I'm in the midst of preparing for our next trip there.

In this post I'll try to answer some of the questions that we are often asked about the course. Probably the most common question is "What do you do in your course?" The second most common must be "How can I teach a course like that?" I'll start with the first question:

What do you do in Guatemala and Belize?

The short answer to this question is a lot. I'll try to summarize.

Our approach to tropical ecology includes the standard elements you'd find in any ecology course: our students read a lot about the ecosystems and the prominent species of plants and animals they're likely to encounter. We teach them what we know about the systems we think we understand, and we tell them about the big gaps in our knowledge that we're aware of - knowing full well that we likely have blind spots we aren't aware of.

In Guatemala this means learning about the ecology of a dense forest growing on a karst plateau, and a deep lake where the water does not circulate much.

In Belize we study the mangroves and the barrier reef. The mangroves are like a porous filter between salt and fresh water, like a cell wall on a macro scale. They serve as a buffer against hurricanes; they keep topsoil from eroding into the sea, and they are a rich and colorful nursery for thousands of species.

The Importance of Human Ecology

We want our students to learn much more than the plants, animals, soil, air, and water, though. Perhaps more than anything, we want them to learn the human ecology of the places we visit. Ecology is not merely an academic study; it is, at its heart, the study of both the world and of our place in it. We don't just look at macaws, jaguars, vines, and ceiba trees; we look at the way our lives - even our visit to these amazing places - affect and are affected by these plants and animals. We don't stay in hotels; we rent rooms in local homes, and we eat meals with local people. We hire local teachers to teach us Spanish and the Itzá language. We study the history of the Itzá people, and we visit ancient ruins. We walk through the forest and camp overnight with local guides who can teach us what they know of that place. We spend time playing soccer with a local youth group, we talk with and listen to local teachers, nurses, physicians, forest rangers, ecologists, NGO volunteers, government officials, town elders, and children. If the ecology of the place matters, surely it matters because these people whose ancestors have lived there for so long matter.

In fact, even if you think they don't matter to you, if you're reading this post in North America these people do matter to you. If their ecology suffers, they will be forced to move to look for new sources of income and food. Simple-minded and disingenuous politicians will tell you this is a problem to be solved by erecting a wall on our border, but walls are a partial solution at best, and at worst, they are blinders that keep us from seeing the source of the problem; walls ignore the real illness and conceal the symptoms, as though willful ignorance were good medicine. The real question - in my mind, anyway - is why anyone who lived on the shores of Lake Petén Itzá would ever want to leave. The answer is that people leave beautiful homes when those homes cease to be liveable. Which means the medicine that is needed is one that treats the illness itself, and not just the symptoms. My students (I hope) return from our course no longer able to see Guatemalan immigrants to the United States as a mere abstraction. Break bread in someone's home and you will see that they are human, too, with lives as particular and intricate and important and rooted as your own. Only when we disturb those roots and strip away the soil must the lives be transplanted.

This is what I mean by human ecology.

Where do you go?

Our time in Guatemala is chiefly in central and northern Petén. Until recently, the landscape of northern Petén was dominated by dense forest, mostly old-growth lowland forests. Surface water is mostly wetlands that vary considerably from one season to the next. There are several small-to-medium-sized rivers, and small streams, but I think a good deal of the water flows underground in karst formations; the Petén has thin soil over a wide karst plateau. There is not much water flowing on the surface. In the center of Petén there is one very deep lake, Lake Petén Itzá. This is a gem in the forest. Flying over it on a sunny day you can see the shallows fade from pale green to rich emerald, and the depths along the north side of the lake plunge to amethyst and dark sapphire. The lake has no obvious inflow or outflow, except a few small streams flowing in from the south and west, and a little creek flowing out in the east.

In Belize we spend most of our time on one of the barrier islands that have no permanent residents. We use that island as a home base from which we can boat out to patch reefs, mangroves, turtle grass beds, deep channels, and the fore-reef. We snorkel with our students in all these places, slowly gathering experiences of similar species in diverse environments, so that the students (and we) can see both the ecology of small places and the web of relations between those small places. In mangroves, for instance, we might see juvenile caribbean reef squid that are a few inches long. When we see them on patch reefs, they might be five or six inches long, and in deep water they might reach eight inches. Each location gives us a glimpse of another stage of their life cycle.

Why do you do this? Aren't you a Humanities professor?

Even if people don't often ask me this, it's obvious that quite a few people think it. Yes, I'm a professor of philosophy and classics, and I teach religion courses, too. But for my whole life I have been fascinated by life underwater. My most recent book was the result of eight years of researching the lives of brook trout in the Appalachian mountains, and much of my research now has to do with ocean and riparian environments in Alaska. I don't do much of what would count as research in the natural sciences, but I do spend a lot of time observing nature. This is both because I find it beautiful, and because I think it's a bad idea to try to formulate ethical principles about things I haven't experienced or seen firsthand. Of course it's not impossible to write policies about things one hasn't done; one needn't commit larceny before writing a law prohibiting theft. But experience teaches me things I might not learn in other ways, and that can keep me from trusting too much in my own opinions. As Aristotle put it,

How Can I Teach A Course Like This? Can others participate in this trip?

The answer to the second of these questions is both yes and no. When I'm in Guatemala and Belize, I'm teaching. Unfortunately, this means I don't have time to bring others along and act as their tour guide.

However, the people I work with in Guatemala - the Asociación Bio-Itzá - would be happy to have you come for a visit. They're in the small town of San Josè, Petèn, Guatemala, right on the north shores of the lake. And this is the answer to the first question. Want to teach such a course? Get in touch with Bio-Itzá and they can help you set it up.

You can get to San José by flying or driving to Flores, then going around the lake by bus or car to San José, about a twenty minute drive.

In San José they have a traditional community medicinal garden. Just north of town is the Bio-Itzá Reserve, where you can go for guided walking tours or overnight stays. It's rustic and gorgeous. (Visits to the Reserve must be arranged in advance through Bio-Itzá.)

When you stay in San José you can easily take a launch (a wooden motor boat) across the lake to Flores, the seat of Nojpetén or Tayasal, the last Maya kingdom that fell to the Spanish.

Flores is a pretty place as well, and I like to take my students to visit ARCAS to see their animal rehabilitation center. (There's a great documentary about that place that was on PBS this year called "Jungle Animal Hospital.")

If you stay in San José, you can also take a short trip (about a half hour by car) to Tikal, or to Yaxhá, both of which are amazingly well-preserved Maya ruins. A little further past Tikal is Uaxactún, where you can see more ruins, and you can also visit a community that is trying to practice sustainable forestry.

This region is not like the tourist areas of Western Guatemala; it's more like the rural frontier of Guatemala, a long-neglected place that is now at risk of being overrun by slash-and-burn forestry, cattle farms, and oil development. It makes me think of the Dakotas over the last century; the population is small and indigenous, and most people in power in Guatemala seem to consider the forest to be a wasteland that is better burned down than preserved. I do not share that view, and while I know that more tourism will bring development and other risks to both culture and forest, the risks are already there in other forms. I hope that ecotourism will offer some counterweight to the other kinds of development that don't seek to preserve the biological integrity or cultural history of this place.

|

| Sunrise on the Barrier Reef in Belize |

In this post I'll try to answer some of the questions that we are often asked about the course. Probably the most common question is "What do you do in your course?" The second most common must be "How can I teach a course like that?" I'll start with the first question:

What do you do in Guatemala and Belize?

The short answer to this question is a lot. I'll try to summarize.

Our approach to tropical ecology includes the standard elements you'd find in any ecology course: our students read a lot about the ecosystems and the prominent species of plants and animals they're likely to encounter. We teach them what we know about the systems we think we understand, and we tell them about the big gaps in our knowledge that we're aware of - knowing full well that we likely have blind spots we aren't aware of.

In Guatemala this means learning about the ecology of a dense forest growing on a karst plateau, and a deep lake where the water does not circulate much.

In Belize we study the mangroves and the barrier reef. The mangroves are like a porous filter between salt and fresh water, like a cell wall on a macro scale. They serve as a buffer against hurricanes; they keep topsoil from eroding into the sea, and they are a rich and colorful nursery for thousands of species.

The Importance of Human Ecology

We want our students to learn much more than the plants, animals, soil, air, and water, though. Perhaps more than anything, we want them to learn the human ecology of the places we visit. Ecology is not merely an academic study; it is, at its heart, the study of both the world and of our place in it. We don't just look at macaws, jaguars, vines, and ceiba trees; we look at the way our lives - even our visit to these amazing places - affect and are affected by these plants and animals. We don't stay in hotels; we rent rooms in local homes, and we eat meals with local people. We hire local teachers to teach us Spanish and the Itzá language. We study the history of the Itzá people, and we visit ancient ruins. We walk through the forest and camp overnight with local guides who can teach us what they know of that place. We spend time playing soccer with a local youth group, we talk with and listen to local teachers, nurses, physicians, forest rangers, ecologists, NGO volunteers, government officials, town elders, and children. If the ecology of the place matters, surely it matters because these people whose ancestors have lived there for so long matter.

|

| Tikal |

|

| The church in San José, Petén, Guatemala |

In fact, even if you think they don't matter to you, if you're reading this post in North America these people do matter to you. If their ecology suffers, they will be forced to move to look for new sources of income and food. Simple-minded and disingenuous politicians will tell you this is a problem to be solved by erecting a wall on our border, but walls are a partial solution at best, and at worst, they are blinders that keep us from seeing the source of the problem; walls ignore the real illness and conceal the symptoms, as though willful ignorance were good medicine. The real question - in my mind, anyway - is why anyone who lived on the shores of Lake Petén Itzá would ever want to leave. The answer is that people leave beautiful homes when those homes cease to be liveable. Which means the medicine that is needed is one that treats the illness itself, and not just the symptoms. My students (I hope) return from our course no longer able to see Guatemalan immigrants to the United States as a mere abstraction. Break bread in someone's home and you will see that they are human, too, with lives as particular and intricate and important and rooted as your own. Only when we disturb those roots and strip away the soil must the lives be transplanted.

This is what I mean by human ecology.

|

| One of my students examining and being examined by nature |

Where do you go?

Our time in Guatemala is chiefly in central and northern Petén. Until recently, the landscape of northern Petén was dominated by dense forest, mostly old-growth lowland forests. Surface water is mostly wetlands that vary considerably from one season to the next. There are several small-to-medium-sized rivers, and small streams, but I think a good deal of the water flows underground in karst formations; the Petén has thin soil over a wide karst plateau. There is not much water flowing on the surface. In the center of Petén there is one very deep lake, Lake Petén Itzá. This is a gem in the forest. Flying over it on a sunny day you can see the shallows fade from pale green to rich emerald, and the depths along the north side of the lake plunge to amethyst and dark sapphire. The lake has no obvious inflow or outflow, except a few small streams flowing in from the south and west, and a little creek flowing out in the east.

|

| My students leap into Lake Petén Itzá to cool off. |

In Belize we spend most of our time on one of the barrier islands that have no permanent residents. We use that island as a home base from which we can boat out to patch reefs, mangroves, turtle grass beds, deep channels, and the fore-reef. We snorkel with our students in all these places, slowly gathering experiences of similar species in diverse environments, so that the students (and we) can see both the ecology of small places and the web of relations between those small places. In mangroves, for instance, we might see juvenile caribbean reef squid that are a few inches long. When we see them on patch reefs, they might be five or six inches long, and in deep water they might reach eight inches. Each location gives us a glimpse of another stage of their life cycle.

|

| My students watch the sunset in Belize |

Why do you do this? Aren't you a Humanities professor?

Even if people don't often ask me this, it's obvious that quite a few people think it. Yes, I'm a professor of philosophy and classics, and I teach religion courses, too. But for my whole life I have been fascinated by life underwater. My most recent book was the result of eight years of researching the lives of brook trout in the Appalachian mountains, and much of my research now has to do with ocean and riparian environments in Alaska. I don't do much of what would count as research in the natural sciences, but I do spend a lot of time observing nature. This is both because I find it beautiful, and because I think it's a bad idea to try to formulate ethical principles about things I haven't experienced or seen firsthand. Of course it's not impossible to write policies about things one hasn't done; one needn't commit larceny before writing a law prohibiting theft. But experience teaches me things I might not learn in other ways, and that can keep me from trusting too much in my own opinions. As Aristotle put it,

“Lack of experience diminishes our power of taking a comprehensive view of the admitted facts. Hence those who dwell in intimate association with nature and its phenomena grow more and more able to formulate, as the foundations of their theories, principles such as to admit of a wide and coherent development: while those whom devotion to abstract discussions has rendered unobservant of the facts are too ready to dogmatize on the basis of a few observations.” Aristotle, De Generatione et corruptione, 316a5-10 (Basic Works, McKeon, trans.)I want to "dwell in intimate association of nature and its phenomena," and being able to formulate better principles is a nice side effect of doing so.

How Can I Teach A Course Like This? Can others participate in this trip?

The answer to the second of these questions is both yes and no. When I'm in Guatemala and Belize, I'm teaching. Unfortunately, this means I don't have time to bring others along and act as their tour guide.

However, the people I work with in Guatemala - the Asociación Bio-Itzá - would be happy to have you come for a visit. They're in the small town of San Josè, Petèn, Guatemala, right on the north shores of the lake. And this is the answer to the first question. Want to teach such a course? Get in touch with Bio-Itzá and they can help you set it up.

You can get to San José by flying or driving to Flores, then going around the lake by bus or car to San José, about a twenty minute drive.

|

| Flores, Petén, Guatemala |

In San José they have a traditional community medicinal garden. Just north of town is the Bio-Itzá Reserve, where you can go for guided walking tours or overnight stays. It's rustic and gorgeous. (Visits to the Reserve must be arranged in advance through Bio-Itzá.)

When you stay in San José you can easily take a launch (a wooden motor boat) across the lake to Flores, the seat of Nojpetén or Tayasal, the last Maya kingdom that fell to the Spanish.

Flores is a pretty place as well, and I like to take my students to visit ARCAS to see their animal rehabilitation center. (There's a great documentary about that place that was on PBS this year called "Jungle Animal Hospital.")

|

| Scarlet macaws being rehabilitated at ARCAS so they can be released back into the wild |

If you stay in San José, you can also take a short trip (about a half hour by car) to Tikal, or to Yaxhá, both of which are amazingly well-preserved Maya ruins. A little further past Tikal is Uaxactún, where you can see more ruins, and you can also visit a community that is trying to practice sustainable forestry.

This region is not like the tourist areas of Western Guatemala; it's more like the rural frontier of Guatemala, a long-neglected place that is now at risk of being overrun by slash-and-burn forestry, cattle farms, and oil development. It makes me think of the Dakotas over the last century; the population is small and indigenous, and most people in power in Guatemala seem to consider the forest to be a wasteland that is better burned down than preserved. I do not share that view, and while I know that more tourism will bring development and other risks to both culture and forest, the risks are already there in other forms. I hope that ecotourism will offer some counterweight to the other kinds of development that don't seek to preserve the biological integrity or cultural history of this place.

∞

Nature As A Classroom

For the last two weeks my students and I have been in Petén, Guatemala, studying the ecology of the region. For half that time we stayed with local families. Our homestays were arranged by the Asociación Bio-Itzá, an indigenous Maya conservation organization that runs a Spanish school to support their work in preserving a section of the Maya Biosphere Reserve. The other half of the time we spent on the reserve and hiking the Ruta Chiclera, a forty-mile trek through the Zotz and Tikal reserves, vast areas of largely unbroken subtropical forest.

These are not always easy conditions. Many hard-working Guatemalans live in poverty that is hard to conceive in our country; it is hot and wet except for when it is cold and wet; biting insects are everywhere; disease and snakes and thorny vines like bayal are constant threats.

But it is also a beautiful place with astonishing biodiversity and remarkable people whose resilience and generosity always make me want to improve my own character. They welcome us into their homes and into their lives, and they are glad to see us come to appreciate the place they live.

I expect that my students will forget much of what I say in my lectures and much of what they read in books. But I doubt very much that they will forget the people they have met here. Guatemala has gone from being an abstraction to a concrete reality. When they meet kind people of good character who have walked across Mexico and made it into the USA only to be caught and deported, "illegal immigrants" now have a face, a home, a family at whose table my students have received a nourishing and welcoming meal.

Likewise, they will not likely forget the sound of howler monkeys at night or the experience of scrambling up Maya temples still covered in a thousand years of trees and soil. They won't forget the long walk in a deep green forest and the smells of tortillas and beans cooked over a wood fire.

It is expensive to bring students so far. One could object that the money could be better spent on viewing the forest online or donating it to rainforest conservation. I disagree. I'm not in the business of dispensing information; I'm in the business of transforming lives, and not much transforms like full-bodied experience. Before we leave for Guatemala my students read papers written by wildlife conservation researchers. In Guatemala they meet those researchers in person and get to hear their stories. They hear in their tone and see in their eyes what brought them to Guatemala and what keeps them here. In such times my students go from taking in data to rethinking their lives.

It is my hope - my exuberant, perhaps not wholly rational hope - that out of such lived experience of nature my students will become people who comfort orphans and widows in their distress, who receive the foreigner into their own homes, who marvel and the world's diversity and who, for the rest of their lives, work to preserve it.

These are not always easy conditions. Many hard-working Guatemalans live in poverty that is hard to conceive in our country; it is hot and wet except for when it is cold and wet; biting insects are everywhere; disease and snakes and thorny vines like bayal are constant threats.

But it is also a beautiful place with astonishing biodiversity and remarkable people whose resilience and generosity always make me want to improve my own character. They welcome us into their homes and into their lives, and they are glad to see us come to appreciate the place they live.

I expect that my students will forget much of what I say in my lectures and much of what they read in books. But I doubt very much that they will forget the people they have met here. Guatemala has gone from being an abstraction to a concrete reality. When they meet kind people of good character who have walked across Mexico and made it into the USA only to be caught and deported, "illegal immigrants" now have a face, a home, a family at whose table my students have received a nourishing and welcoming meal.

Likewise, they will not likely forget the sound of howler monkeys at night or the experience of scrambling up Maya temples still covered in a thousand years of trees and soil. They won't forget the long walk in a deep green forest and the smells of tortillas and beans cooked over a wood fire.

It is expensive to bring students so far. One could object that the money could be better spent on viewing the forest online or donating it to rainforest conservation. I disagree. I'm not in the business of dispensing information; I'm in the business of transforming lives, and not much transforms like full-bodied experience. Before we leave for Guatemala my students read papers written by wildlife conservation researchers. In Guatemala they meet those researchers in person and get to hear their stories. They hear in their tone and see in their eyes what brought them to Guatemala and what keeps them here. In such times my students go from taking in data to rethinking their lives.

It is my hope - my exuberant, perhaps not wholly rational hope - that out of such lived experience of nature my students will become people who comfort orphans and widows in their distress, who receive the foreigner into their own homes, who marvel and the world's diversity and who, for the rest of their lives, work to preserve it.

∞

The Howler Monkeys of Petén, Guatemala

Each year I co-teach a January-term class on tropical ecology in Guatemala and Belize.

One of my favorite experiences when I return to Guatemala is hearing the howler monkeys at night. Their voices travel for miles through the forest, it seems. My students are often alarmed by the noise, because the monkeys will approach silently and then begin to howl in the treetops overhead with voices that seem to belong to something much bigger than a mono aullador, as they are called in Spanish.

During one of my last trips I made this video. We were setting up camp in the Mayan Biosphere Reserve, or Biosfera Maya, en route to Tikal, when several troops of howlers began to sing nearby. We followed the voices to one of the nearest troops so we could get a closer look at these gentle beauties, our placid arboreal cousins. Enjoy the sound.

|

| One of the wonders of the Mayan Biosphere Reserve |

During one of my last trips I made this video. We were setting up camp in the Mayan Biosphere Reserve, or Biosfera Maya, en route to Tikal, when several troops of howlers began to sing nearby. We followed the voices to one of the nearest troops so we could get a closer look at these gentle beauties, our placid arboreal cousins. Enjoy the sound.

If you're interested in bringing your students to this fairly

well-preserved rainforest and arranging local guides, you might check

out the Asociación Bio-Itzá, an indigenous Mayan group dedicated to

preserving their forest, their ancestral knowledge, and their language.

They have a small rustic facility on their rainforest reserve and a

Spanish-language school for foreigners (with very reasonable prices) on the north shore of Lake Petén

Itzá, not far from the airport at Flores and from the beautiful ruins of

Tikal.

*****

(A friend tells me he extracted the sound from this video of mine and uploaded it to the wikipedia page on howler monkeys.)

∞

and it's also a short trip to Tikal:

They also have a school for teaching indigenous Mayan languages like Itzá, Quiché, and Kekchí.

There are some slightly cheaper language schools in Guatemala, but this one makes your money go a long way, since they use the income to preserve and protect one of the largest unbroken stretches of rainforest North of the Amazon, and to preserve indigenous culture, protect archaeological sites, and promote sustainable agriculture. In addition to learning Spanish, you can learn about medicinal plants; local cooking, music, and culture; rainforest ecology; Mayan archaeology (they have a licensed archaeologist on their staff); and a lot more. Students interested in rural medicine can ask about arranging to work in the local medical clinic. Worth every penny.

(Thanks to Luke Lynass and the other Augustana College students who worked to get this new website up and running.)

New Bio-Itzá Website!

Check it out.

The Asociación Bio Itzá does great, inexpensive Spanish-language immersion programs for individuals or groups in Petén, Guatemala. It’s a short trip from the Flores airport to their school and homestays in San José:

and it's also a short trip to Tikal:

They also have a school for teaching indigenous Mayan languages like Itzá, Quiché, and Kekchí.

There are some slightly cheaper language schools in Guatemala, but this one makes your money go a long way, since they use the income to preserve and protect one of the largest unbroken stretches of rainforest North of the Amazon, and to preserve indigenous culture, protect archaeological sites, and promote sustainable agriculture. In addition to learning Spanish, you can learn about medicinal plants; local cooking, music, and culture; rainforest ecology; Mayan archaeology (they have a licensed archaeologist on their staff); and a lot more. Students interested in rural medicine can ask about arranging to work in the local medical clinic. Worth every penny.

(Thanks to Luke Lynass and the other Augustana College students who worked to get this new website up and running.)

∞

This is a small, non-profit group run by a few devoted individuals who are trying to preserve their language, their forests, their modes of agriculture, and their communities. They teach Spanish by full immersion, providing four hours a day of individual instruction tailored to your needs, homestays with delightful local families, and the opportunity to experience both contemporary Guatemalan and traditional Mayan cultures.

So why am I writing about this? Because their Spanish school is their means of raising money to support a number of other important endeavors including:

Learn Spanish in Guatemala, Help Save the Rainforest

I think the best way to learn a language is to immerse yourself in it. Read books in the language you want to learn, eat the food of its cultures, and, if at all possible, travel to where it is spoken.

If you’re thinking about doing this with Spanish, let me recommend a place to do this in Guatemala: the Asociación Bio-Itzá in San José, Petén, Guatemala, on the Northwest shore of Lake Petén-Itzá.

This is a small, non-profit group run by a few devoted individuals who are trying to preserve their language, their forests, their modes of agriculture, and their communities. They teach Spanish by full immersion, providing four hours a day of individual instruction tailored to your needs, homestays with delightful local families, and the opportunity to experience both contemporary Guatemalan and traditional Mayan cultures.

So why am I writing about this? Because their Spanish school is their means of raising money to support a number of other important endeavors including: