Book of Common Prayer

- Forgive Onesimus, the indentured servant who ran away, breaking his contract with Philemon;

- Forgive Onesimus for stealing from Philemon as he fled;

- Welcome Onesimus back, not as a slave but as a family member.

∞

Reason For Hope

Nearly every spring term I teach a class called “Theology and Philosophy in Dialogue.” I inherited the title and the course description when I started teaching at my current school in 2005. Each year the course changes a little, in response to my students and what I perceive to be relevant themes in our world and culture.

Apologetics and Postmodernism

When I first taught it, I made it a class about apologetics and postmodernism. By “apologetics” I mean the work of giving a reasoned account of one’s commitments; by “postmodernism,” I mean the suspicion that what look like reasoned accounts might have unexamined depths and layers to them. In the context of theism—and in particular Christian theism—apologetics has a long history that reaches back to the early years of Christianity. Saint Peter wrote in his longer letter that Christians should always be prepared to give a reasoned defense of the hope they bore within them. That phrase “reasoned defense” is a translation of the Greek word apologia, which can mean a legal defense, and from which we get our word “apologetics.”

When Saint Paul of Tarsus found himself in Athens, speaking to Stoic and Epicurean philosophers on the Areopagus, he tried to explain his beliefs not in the terms of his culture but in theirs. He doesn’t seem to have won many over to his views that day, but if nothing else was accomplished, at the end of the conversation it was clearer where Paul and the Greek philosophers were in agreement and where they disagreed. If immediate conversion was the aim of his speech, it wasn’t a great speech. But if he aimed to build a bridge of mutual understanding, I’d say he was pretty successful.

One of the keys to his success, I think, was familiarity with the culture around him. I’ve written about this elsewhere, so I won’t belabor it here, but I’ll just point out that Paul quoted two Greek philosophical poets, Epimenides and Aratos, and he did so in a culturally appropriate and significant place, since several centuries before Paul’s travels, Epimenides (who was from Crete) also traveled to Athens and also spoke on the Areopagus about the gods and salvation.

Understanding Atheism(s)

A few years after I started teaching that course, I shifted the course to take seriously the “New Atheists.” I figured that if my religious students graduated without hearing the strongest challenges to their faith, I, as a professor who teaches theology, was letting them down. I wanted them to know that soon they’d hear strong arguments against their religious heritage, beliefs, and practices, and that these arguments should be taken seriously. For my Christian students, I framed this as a way of living the commandment to love God with one’s mind.

Of course, only some of my students are religious, and some of the religious students aren’t Christians. (I’m at a Lutheran university in a small Midwestern city, so until recently most of them were at least culturally Christian; that’s changing quickly, though.) I wanted this to be a class that was helpful for everyone, so I started to turn this into a class about mutual understanding. I now teach my students how to distinguish between a dozen different kinds of (and reasons for) atheism, lest they make the mistake of oversimplifying the complexity of their neighbors and of themselves.

Understanding and Agapic Love

Arguments about religion can quickly become unkind. Many of us have been wounded in the name of religion, and those wounds heal slowly, if at all. How could we make this into a class that was—on its surface, and in its content—about theology and philosophy, while really making it about something like mutual care?

I just mentioned that great commandment: Love God with your heart, soul, mind, and strength, Jesus said, echoing Moses. Then he added a second commandment: love your neighbor as yourself. Everything else hangs on these two commandments, he said.

Explaining those two commandments would be almost as hard as trying to keep them, so I won’t try to do so here. I’ll just point out that it’s fascinating to command someone to love someone else; that the love that’s called for here is agapic love, i.e. the love that seeks the good and flourishing of the beloved; and that the commandments are so lacking in specificity as to call for both extensive commentary and continued practice. They’re vague commandments, which means they require us to work them out in community, over time. And in all likelihood we’ll never get them right. That may seem like a weakness, but it also strikes me as offering the freedom to try and to fail and to help one another to try again.

Anxiety, Ultimate Concerns, and Societal “Stress Fractures”

Which brings me to the most recent incarnation of my Theology and Philosophy in Dialogue class. Over the last few years it seems to me that my students have become more anxious about their economic futures, more stressed about exams and jobs, more focused on education and work as competition for rank. I could be wrong, but as the stress and anxiety have grown, it seems like my students are so busy jockeying for position that they have a hard time putting the cause of their stress into words. On top of all this, here in the United States, it feels like we’ve been using stronger words so that we can give voice to our anxiety more quickly. We aren’t broken, but we’ve got lots of hairline stress fractures that are too small to see. We aren’t bleeding, but we’ve got a constant dull ache.

In other words, it seems like we’re fearful without being able to identify the object of our fear, and that has us prepared to see enemies wherever we look. This does not make it easy to love our neighbors as ourselves (unless we also have that kind of distrust of ourselves, which is a real possibility, I suppose.) And at least in the way Paul Tillich described God: whatever we regard as our ultimate concern functions as our God. When economic anxiety, jostling for rank, or fear of losing one’s place in the future, (these are all ways of saying the same thing, I think) take on the role of “ultimate concern” in our lives, they become our gods.

The course I’m teaching this semester still has traces of every previous semester’s influences. We talk a little about apologetics, and that’s a helpful way of teaching students about logic, inference, probability, and certainty. (Ask some of them about “doxastic certainty” or my “haystack problem” and you’ll see what I mean.)

And we still talk about postmodernism, though as my career has shifted from the philosophy of religion to environmental philosophy, ethics, and policy, I’m inclined to follow Scott Russell Sanders’ view (see note, below) that if we spend too much time theorizing and not enough time caring for the world we share, incredulity towards metanarratives can quickly become a new metanarrative that we fail to examine sufficiently.

And we still talk about atheisms. This semester I have sketched a dozen forms of atheism once again, and we’re now working our way through them.

Friendship, and “Best Construction”

But the aim of the class, more than anything, is friendship.

I told all the students that this was the case on the first day of class.

And here, I think, is where Theology and Philosophy can have a really helpful dialogue in our time. I teach at a Lutheran university, so it’s fitting to invoke Luther. In his Small Catechism, he offers some commentary on the Ten Commandments. His commentary on the eighth commandment is helpful. The commandment reads simply, like this:

This is hard.

“A Mutual, Joint-Stock World, In All Meridians”

It’s especially hard when we feel that others are getting ahead of us, and that we are in a competition with everyone else. If the world is a zero-sum game, then everyone run, and the Devil take the hindmost. But what if Queequeg is right? When Queequeg sees a fellow sailor drowning and no one moves to save the sailor, Queequeg leaps into the water to save his fellow. There is no question of whether they are of the same tribe, the same party, the same race, the same team. Queequeg is, as far as anyone aboard the ship knows, a cannibal. And yet the narrator, observing Queequeg’s agapic care for his fellow sailor, offers this comment:

It’s much easier to approach theological conversations with the idea that our theology is a weapon and that our enemies are those with whom we disagree. It’s so easy to forget what Saint Paul wrote, that we don’t fight against flesh and blood, but against far less tangible, invisible forces that would have us view our neighbors with malice.

Could we approach theology the way Queequeg approaches the plight of his fellow sailor? Is it possible to maintain one’s cherished beliefs while recognizing that one’s object of “ultimate concern” might be something we don’t yet see with certainty and clarity? I cannot speak for others, so I’ll just offer this confession: I’m aware of a capacity in myself to care more for my theology than for the God that my theology claims to describe. In simpler terms: my own theology can become so dear to me that it becomes an idol, displacing the very God I set out to love and serve. And how to I love and serve my God? So far, the best I can offer you is this: I should love God with all I am, and I should love my neighbor as myself. Does that seem unclear to you? It does to me. Which means I need all the help I can get in clarifying my vision. Right now I see in a glass, darkly.

The philosopher Jonathan Lear suggests a principle akin to Queequeg’s, and to Luther’s: the principle of humanity. He describes it like this:

Conclusion

It’s appropriate to me that I teach this course in Lent each year. Lent is a good time for self-examination, and that includes an examination of all kinds of pieties and supposed certainties. What is it that we hold to be of ultimate concern? What do we love with all our heart, soul, mind, and strength? That might just be playing the role of a god in our lives. If so, does that God help us to love our neighbors as ourselves?

I could be wrong in all I say in this class. I enter it with “fear and trembling,” knowing that there’s so much I don’t know, and knowing that many of my students might be wiser than I am. I know they might have seen the divine far more clearly than I ever will in this life.

But oh, how I want them to live well, not to be entangled by anxious grief, not to be afraid of the future, not to be burdened by relentless suspicions and fears.

Yes, there are other subjects I could teach, and yes, there are other jobs I could do. But for me, right now, this one feels like a good way to reexamine my own ultimate concerns, and a good way to help others to do the same. May I do so without malice, with agapic love, and with the constant practice of putting the best construction on everything.

Amen. Lord, have mercy.

*****

Notes:

* Scott Russell Sanders: I'm thinking of his essay, "The Warehouse and the Wilderness," and in particular the opening pages of that essay. You can find it in A Conservationist Manifesto, beginning on page 71. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009)

* Ulpian's words are cited in Justinian, Institutes, Book 1, Title 1, Sec. 3.

* Lear has an endnote at the end of this sentence. It reads: “This principle is also known as the ‘principle of charity,’ and the most famous arguments for it are given by Donald Davidson. See his “Radical Interpretation,” in Inquiries Into Truth And Interpretation (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984), pp. 136-137; “Belief and the Basis of Meaning,” ibid., pp. 152-153; “Thought and Talk,” ibid., pp. 168-169; “On the Very Idea of a Conceptual Scheme,” ibid., pp. 196-197; “The Method of Truth in Metaphysics,” ibid., pp. 200-201.”

Apologetics and Postmodernism

When I first taught it, I made it a class about apologetics and postmodernism. By “apologetics” I mean the work of giving a reasoned account of one’s commitments; by “postmodernism,” I mean the suspicion that what look like reasoned accounts might have unexamined depths and layers to them. In the context of theism—and in particular Christian theism—apologetics has a long history that reaches back to the early years of Christianity. Saint Peter wrote in his longer letter that Christians should always be prepared to give a reasoned defense of the hope they bore within them. That phrase “reasoned defense” is a translation of the Greek word apologia, which can mean a legal defense, and from which we get our word “apologetics.”

When Saint Paul of Tarsus found himself in Athens, speaking to Stoic and Epicurean philosophers on the Areopagus, he tried to explain his beliefs not in the terms of his culture but in theirs. He doesn’t seem to have won many over to his views that day, but if nothing else was accomplished, at the end of the conversation it was clearer where Paul and the Greek philosophers were in agreement and where they disagreed. If immediate conversion was the aim of his speech, it wasn’t a great speech. But if he aimed to build a bridge of mutual understanding, I’d say he was pretty successful.

One of the keys to his success, I think, was familiarity with the culture around him. I’ve written about this elsewhere, so I won’t belabor it here, but I’ll just point out that Paul quoted two Greek philosophical poets, Epimenides and Aratos, and he did so in a culturally appropriate and significant place, since several centuries before Paul’s travels, Epimenides (who was from Crete) also traveled to Athens and also spoke on the Areopagus about the gods and salvation.

Understanding Atheism(s)

A few years after I started teaching that course, I shifted the course to take seriously the “New Atheists.” I figured that if my religious students graduated without hearing the strongest challenges to their faith, I, as a professor who teaches theology, was letting them down. I wanted them to know that soon they’d hear strong arguments against their religious heritage, beliefs, and practices, and that these arguments should be taken seriously. For my Christian students, I framed this as a way of living the commandment to love God with one’s mind.

Of course, only some of my students are religious, and some of the religious students aren’t Christians. (I’m at a Lutheran university in a small Midwestern city, so until recently most of them were at least culturally Christian; that’s changing quickly, though.) I wanted this to be a class that was helpful for everyone, so I started to turn this into a class about mutual understanding. I now teach my students how to distinguish between a dozen different kinds of (and reasons for) atheism, lest they make the mistake of oversimplifying the complexity of their neighbors and of themselves.

Understanding and Agapic Love

Arguments about religion can quickly become unkind. Many of us have been wounded in the name of religion, and those wounds heal slowly, if at all. How could we make this into a class that was—on its surface, and in its content—about theology and philosophy, while really making it about something like mutual care?

I just mentioned that great commandment: Love God with your heart, soul, mind, and strength, Jesus said, echoing Moses. Then he added a second commandment: love your neighbor as yourself. Everything else hangs on these two commandments, he said.

Explaining those two commandments would be almost as hard as trying to keep them, so I won’t try to do so here. I’ll just point out that it’s fascinating to command someone to love someone else; that the love that’s called for here is agapic love, i.e. the love that seeks the good and flourishing of the beloved; and that the commandments are so lacking in specificity as to call for both extensive commentary and continued practice. They’re vague commandments, which means they require us to work them out in community, over time. And in all likelihood we’ll never get them right. That may seem like a weakness, but it also strikes me as offering the freedom to try and to fail and to help one another to try again.

Anxiety, Ultimate Concerns, and Societal “Stress Fractures”

Which brings me to the most recent incarnation of my Theology and Philosophy in Dialogue class. Over the last few years it seems to me that my students have become more anxious about their economic futures, more stressed about exams and jobs, more focused on education and work as competition for rank. I could be wrong, but as the stress and anxiety have grown, it seems like my students are so busy jockeying for position that they have a hard time putting the cause of their stress into words. On top of all this, here in the United States, it feels like we’ve been using stronger words so that we can give voice to our anxiety more quickly. We aren’t broken, but we’ve got lots of hairline stress fractures that are too small to see. We aren’t bleeding, but we’ve got a constant dull ache.

In other words, it seems like we’re fearful without being able to identify the object of our fear, and that has us prepared to see enemies wherever we look. This does not make it easy to love our neighbors as ourselves (unless we also have that kind of distrust of ourselves, which is a real possibility, I suppose.) And at least in the way Paul Tillich described God: whatever we regard as our ultimate concern functions as our God. When economic anxiety, jostling for rank, or fear of losing one’s place in the future, (these are all ways of saying the same thing, I think) take on the role of “ultimate concern” in our lives, they become our gods.

The course I’m teaching this semester still has traces of every previous semester’s influences. We talk a little about apologetics, and that’s a helpful way of teaching students about logic, inference, probability, and certainty. (Ask some of them about “doxastic certainty” or my “haystack problem” and you’ll see what I mean.)

And we still talk about postmodernism, though as my career has shifted from the philosophy of religion to environmental philosophy, ethics, and policy, I’m inclined to follow Scott Russell Sanders’ view (see note, below) that if we spend too much time theorizing and not enough time caring for the world we share, incredulity towards metanarratives can quickly become a new metanarrative that we fail to examine sufficiently.

And we still talk about atheisms. This semester I have sketched a dozen forms of atheism once again, and we’re now working our way through them.

Friendship, and “Best Construction”

But the aim of the class, more than anything, is friendship.

I told all the students that this was the case on the first day of class.

And here, I think, is where Theology and Philosophy can have a really helpful dialogue in our time. I teach at a Lutheran university, so it’s fitting to invoke Luther. In his Small Catechism, he offers some commentary on the Ten Commandments. His commentary on the eighth commandment is helpful. The commandment reads simply, like this:

“Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor.”Like the other commandments I’ve mentioned, it is only a few words long. And like those others, it leaves room for commentary. Luther’s commentary does something that I find very helpful. While the commandment is negative (“thou shalt not,” it says) Luther thought that alongside each negative commandment was something positive. So he writes:

What does this mean?--Answer. We should fear and love God that we may not deceitfully belie, betray, slander, or defame our neighbor, but defend him, [think and] speak well of him, and put the best construction on everything.”This is akin to what Plato offers in several ways in his Republic, and to Ulpian’s legal principle of “giving to each person their due,” (see note, below) but it goes a little further, with an agapic tinge: Luther doesn’t just tell us not to lie, nor does he tell us to be simply honest, but to put the best construction on everything.

This is hard.

“A Mutual, Joint-Stock World, In All Meridians”

It’s especially hard when we feel that others are getting ahead of us, and that we are in a competition with everyone else. If the world is a zero-sum game, then everyone run, and the Devil take the hindmost. But what if Queequeg is right? When Queequeg sees a fellow sailor drowning and no one moves to save the sailor, Queequeg leaps into the water to save his fellow. There is no question of whether they are of the same tribe, the same party, the same race, the same team. Queequeg is, as far as anyone aboard the ship knows, a cannibal. And yet the narrator, observing Queequeg’s agapic care for his fellow sailor, offers this comment:

Was there ever such unconsciousness? He did not seem to think that he at all deserved a medal from the Humane and Magnanimous Societies. He only asked for water—fresh water—something to wipe the brine off; that done, he put on dry clothes, lighted his pipe, and leaning against the bulwarks, and mildly eyeing those around him, seemed to be saying to himself—“It’s a mutual, joint-stock world, in all meridians. We cannibals must help these Christians.” -- Herman Melville, Moby Dick. (New York: Signet, 1980) 76

It’s much easier to approach theological conversations with the idea that our theology is a weapon and that our enemies are those with whom we disagree. It’s so easy to forget what Saint Paul wrote, that we don’t fight against flesh and blood, but against far less tangible, invisible forces that would have us view our neighbors with malice.

Could we approach theology the way Queequeg approaches the plight of his fellow sailor? Is it possible to maintain one’s cherished beliefs while recognizing that one’s object of “ultimate concern” might be something we don’t yet see with certainty and clarity? I cannot speak for others, so I’ll just offer this confession: I’m aware of a capacity in myself to care more for my theology than for the God that my theology claims to describe. In simpler terms: my own theology can become so dear to me that it becomes an idol, displacing the very God I set out to love and serve. And how to I love and serve my God? So far, the best I can offer you is this: I should love God with all I am, and I should love my neighbor as myself. Does that seem unclear to you? It does to me. Which means I need all the help I can get in clarifying my vision. Right now I see in a glass, darkly.

The philosopher Jonathan Lear suggests a principle akin to Queequeg’s, and to Luther’s: the principle of humanity. He describes it like this:

“The interpretation thus fits what philosophers call the principle of humanity: that we should try to interpret others as saying something true—guided by our own sense of what is true and of what they could reasonably believe.” -- Jonathan Lear, Radical Hope. 4 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006) (See note below)The Episcopal Church’s Book of Common Prayer offers another commentary on the fourth commandment, the commandment not to take the name of God in vain. The Book of Common Prayer rephrases the commandment like this:

You shall not invoke with malice the Name of the Lord your God.

Amen. Lord have mercy.The rephrasing is a commentary on “in vain.” Invoking God’s name in vain is equated with invoking it with malice, that is, with the opposite of agapic love.

Conclusion

It’s appropriate to me that I teach this course in Lent each year. Lent is a good time for self-examination, and that includes an examination of all kinds of pieties and supposed certainties. What is it that we hold to be of ultimate concern? What do we love with all our heart, soul, mind, and strength? That might just be playing the role of a god in our lives. If so, does that God help us to love our neighbors as ourselves?

I could be wrong in all I say in this class. I enter it with “fear and trembling,” knowing that there’s so much I don’t know, and knowing that many of my students might be wiser than I am. I know they might have seen the divine far more clearly than I ever will in this life.

But oh, how I want them to live well, not to be entangled by anxious grief, not to be afraid of the future, not to be burdened by relentless suspicions and fears.

Yes, there are other subjects I could teach, and yes, there are other jobs I could do. But for me, right now, this one feels like a good way to reexamine my own ultimate concerns, and a good way to help others to do the same. May I do so without malice, with agapic love, and with the constant practice of putting the best construction on everything.

Amen. Lord, have mercy.

*****

Notes:

* Scott Russell Sanders: I'm thinking of his essay, "The Warehouse and the Wilderness," and in particular the opening pages of that essay. You can find it in A Conservationist Manifesto, beginning on page 71. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009)

* Ulpian's words are cited in Justinian, Institutes, Book 1, Title 1, Sec. 3.

* Lear has an endnote at the end of this sentence. It reads: “This principle is also known as the ‘principle of charity,’ and the most famous arguments for it are given by Donald Davidson. See his “Radical Interpretation,” in Inquiries Into Truth And Interpretation (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984), pp. 136-137; “Belief and the Basis of Meaning,” ibid., pp. 152-153; “Thought and Talk,” ibid., pp. 168-169; “On the Very Idea of a Conceptual Scheme,” ibid., pp. 196-197; “The Method of Truth in Metaphysics,” ibid., pp. 200-201.”

∞

The Slow, Important Work Of Poetry

At the time it seemed like chance that brought me to minor in comparative poetry in college.

Without having a master plan, over four years I wound up taking a number of poetry classes in four languages. Eventually I asked my college to consider them a new minor area of study. They agreed, and I graduated.

And then, slowly, over a quarter century, I began reading more poetry in more languages. It's always slow; I can't pick up a book of poems and read it like a novel. If the poetry is any good at all, I can read one or two poems, and then I've got to put the book down and let the words sit with me.

Often, I go back and read the same poem again, and again.

The very best poems I try to memorize, even though my memory for verse has never been good. I imagine most people would consider that a useless exercise, a waste of storage space in an already cluttered brain.

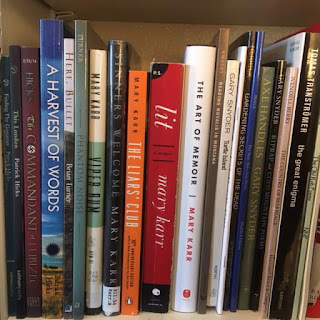

But in each season of my life I've found that it is some form of poetry that acts as salve to my soul's wounds or food that sustains its long journey forward. Homer's long story-poems; old epics and sagas from Ireland and Wales and Iceland; Vedic verses and Greek scriptures; Gregorian chants that have echoed in stone chambers for centuries; Shakespeare's or Petrarch's sonnets; the Psalms and proverbs of Hebrew priests and kings; a few words put together well by Dylan Thomas, Gary Snyder, Tomas Tranströmer, or C.S. Lewis; or the timely phrases of some of my favorite contemporaries like Patrick Hicks, Abigail Carroll, Mary Karr, Wendell Berry, Melissa Kwasny, John Lane, or Brian Turner. Each of them has, at some point, given me the daily bread I craved.

I can't seem to predict when the need will arise, but suddenly, there it is, and I find myself quoting Joachim du Bellay's sonnet about travel, and home:

That sonnet often reminds me, in turn, of verses about Abraham.

I am no good at praying, but I often wish I were. I think the fact that we make light of prayer - both by mocking those who pray and by being those who speak piously of prayer but who do not allow ourselves to confess the weakness prayer implies - says something of another shared longing, not unlike the longing for home. We long to comfort those far away when tragic events fall on them. They may be total strangers, but we know how horrible we would feel in their place, and we know that right now there is nothing we can do to staunch the flow of pain for them. But we can hold them in the center of our consciousness and, for a little while, not let any lesser thoughts crowd them out of our hearts and minds. We can, for a little while, consider our lives to be connected to theirs. We can, for a little while, ask ourselves what we might do to change the world so that this pain will not be inflicted on others.

Since I am not adept at praying, In those times I find the prayers of others buoy me up above the waves of emotional tempest. The prayer books of my tradition - the various versions of The Book of Common Prayer - often transform my anguish into something articulate. Of course, we turn to that same book when a baby is born, when a couple is wed, and when our beloved are interred. These events? We know they are coming, and yet it is not easy to prepare oneself, to be always ready for those days. I live in a tent; poetry often gives me a foundation to build on, and the better I've memorized it, the stronger that foundation becomes.

Those words, buried like seeds, slowly come to bear fruit in my life. Sometimes I wonder: was it really chance that brought me to the poems?

In the hardest of times, and also in the most joyful times, the words of poets are like a cup of water in a dry place. They refresh me, and they clear my throat so that I can take in that which sustains my own life, and speak other words, both old and new, that may sustain the lives of others.

Without having a master plan, over four years I wound up taking a number of poetry classes in four languages. Eventually I asked my college to consider them a new minor area of study. They agreed, and I graduated.

And then, slowly, over a quarter century, I began reading more poetry in more languages. It's always slow; I can't pick up a book of poems and read it like a novel. If the poetry is any good at all, I can read one or two poems, and then I've got to put the book down and let the words sit with me.

Often, I go back and read the same poem again, and again.

The very best poems I try to memorize, even though my memory for verse has never been good. I imagine most people would consider that a useless exercise, a waste of storage space in an already cluttered brain.

But in each season of my life I've found that it is some form of poetry that acts as salve to my soul's wounds or food that sustains its long journey forward. Homer's long story-poems; old epics and sagas from Ireland and Wales and Iceland; Vedic verses and Greek scriptures; Gregorian chants that have echoed in stone chambers for centuries; Shakespeare's or Petrarch's sonnets; the Psalms and proverbs of Hebrew priests and kings; a few words put together well by Dylan Thomas, Gary Snyder, Tomas Tranströmer, or C.S. Lewis; or the timely phrases of some of my favorite contemporaries like Patrick Hicks, Abigail Carroll, Mary Karr, Wendell Berry, Melissa Kwasny, John Lane, or Brian Turner. Each of them has, at some point, given me the daily bread I craved.

I can't seem to predict when the need will arise, but suddenly, there it is, and I find myself quoting Joachim du Bellay's sonnet about travel, and home:

Heureux qui, comme Ulysse, a fait un beau voyage

Ou comme cestuy-là qui conquit la toison

Et puis est retourné, plein d'usage et raison

Vivre entre ses parents le reste de son âgeHis simple words save me from forming new ones and free me to think and feel as the occasion demands; his words give utterance to what I find welling up inside me. His words change my homesickness into a stage in a worthwhile journey. Here is a very loose translation of those lines: "Happy is he who, like Ulysses, made a beautiful journey, or like that man who seized the Golden Fleece, and then traveled home again, full of wisdom, to live the rest of his life with his family." We are pulled in both directions at once: towards the Golden Fleece and adventures in Troy, and towards the home we left behind when we departed on our quest.

That sonnet often reminds me, in turn, of verses about Abraham.

Consider Abraham, who dwelled in tents,

because he was looking forward to a city with foundations.This longing for home that I sometimes have when I travel is itself no alien in any land. We all may feel it in any place. Everyone feels lost sometimes. Knowing that others have found words to express their feeling of being lost is itself a reminder that we are not alone. Hölderlin's opening words in his poem about St. John's exile on Patmos say this well:

Nah ist, und schwer zu fassen, der GottIt does seem that God - like home and family and love and neighbors - is close enough to grasp, so close that we could meaningfully touch them all right now. And yet so far that nothing but our words can draw near.

I am no good at praying, but I often wish I were. I think the fact that we make light of prayer - both by mocking those who pray and by being those who speak piously of prayer but who do not allow ourselves to confess the weakness prayer implies - says something of another shared longing, not unlike the longing for home. We long to comfort those far away when tragic events fall on them. They may be total strangers, but we know how horrible we would feel in their place, and we know that right now there is nothing we can do to staunch the flow of pain for them. But we can hold them in the center of our consciousness and, for a little while, not let any lesser thoughts crowd them out of our hearts and minds. We can, for a little while, consider our lives to be connected to theirs. We can, for a little while, ask ourselves what we might do to change the world so that this pain will not be inflicted on others.

Since I am not adept at praying, In those times I find the prayers of others buoy me up above the waves of emotional tempest. The prayer books of my tradition - the various versions of The Book of Common Prayer - often transform my anguish into something articulate. Of course, we turn to that same book when a baby is born, when a couple is wed, and when our beloved are interred. These events? We know they are coming, and yet it is not easy to prepare oneself, to be always ready for those days. I live in a tent; poetry often gives me a foundation to build on, and the better I've memorized it, the stronger that foundation becomes.

Those words, buried like seeds, slowly come to bear fruit in my life. Sometimes I wonder: was it really chance that brought me to the poems?

In the hardest of times, and also in the most joyful times, the words of poets are like a cup of water in a dry place. They refresh me, and they clear my throat so that I can take in that which sustains my own life, and speak other words, both old and new, that may sustain the lives of others.

∞

A Visible Sign

This morning my wife, my kids, and I sat around the Christmas tree and opened the gifts we gave one another. Just as we were finishing, my wife's phone rang.

One of her parishioners was coming down from a bad high in a bad way. The police were on the scene, and the whole family was understandably distressed.

I don't know many details, because as a priest she has to keep confidences. All I know is that her parishioners were asking for her to come and help before things got out of hand.

I don't know many details, because as a priest she has to keep confidences. All I know is that her parishioners were asking for her to come and help before things got out of hand.

Which raises the question, "How can a minister possibly help?" She hasn't got a badge or a gun, so she can't arrest people and lock them up; she doesn't have a medical license, so she can't prescribe medications; she isn't a judge who can order someone to be placed in protective custody.

All she can do is be present with those who are suffering. She can listen to those to whom no one else will listen. She can pray with them, helping to connect those who are suffering with words to express that suffering. She can deliver the sacrament, a visible and outward sign of indelible connection to a bigger community, reminding the lonely that they are not alone.

She quickly got out of her pajamas, put on a black shirt and her clerical collar, and picked up her Book of Common Prayer. I kissed her before she went out the door, aware that she was going to a home where there was a troubled family, a belligerent drug user, and eight armed men charged with upholding the law. Oh, boy. "Do you want some company?" I asked, knowing there wasn't much I could offer besides that. She said she'd be fine.

As she left, and the kids continued to examine their gifts, I sat and silently prayed (reluctantly, as always), joining her in her work in that small way.

I admit that I do not like church. I can think of far pleasanter ways to spend my Sunday morning than leaving my house to stand, and sit, and kneel with a hundred relative strangers.

But this is one thing I love about churches: this deeply democratic commitment to including everyone in the community. No one is to be left out. No one gets more bread or more wine at the altar. Everyone who needs solace, or penance, or forgiveness, or company, may have it.

The Book Of The Acts Of The Apostles, the fifth book of the Greek testament, tells the story of the early church as a place where people who needed food or money or other kinds of sustenance could come and find them. Early on in that book we even see the story of how the church made a special office for people whose job it would be to oversee the equitable distribution of food to the poor.

I think highly of my own profession of teaching, because I think it serves a high social good. But I teach in a small, selective liberal arts college. Most of the people I serve have their lives pretty much together. In general, they can pay their bills, they don't have huge drug or legal issues, they have supportive communities, they can think and write well. Yes, most of them struggle with money and other things, but they keep their heads above water, and their futures are bright.

My wife, on the other hand, has a much broader "clientele." She serves the congregations at our cathedral and several other parishes. Her congregants range from the powerful and wealthy to the poorest of the poor. Here in South Dakota more than half our diocese are Native Americans, and many more are refugees from conflicts in east Africa. Ethnically, racially, economically, liturgically, and politically, this is a diverse group.

And again, it is a group where everyone is - or at least ought to be - welcome.

The church has always failed to live up to its ideals. I don't dispute that. Show me an institution that has good ideals and that always lives up to them, and I'll readily tip my hat to it. What I love in the church is that it has these ideals and it has daily, weekly, and annual rituals by which we remind ourselves what those ideals are. We screw them up, we distort and bastardize them, we even sell them to high bidders from time to time when we lose our heads and our hearts. But then we remind ourselves that we should not. And we have institutions and rituals of returning to the path we've departed from.

We will probably always get it wrong. I'm okay with that, as long as we keep turning back towards what is right, as long as we maintain these traditions and rituals of self-examination and self-correction. And as long as we cherish this ideal of welcoming everyone, absolutely everyone. I don't mean just saying we welcome everyone, but I mean doing it.

Again, I work at a small college. Colleges are places where we all talk a good game about being welcoming, and for the most part, we manage to practice what we preach, given the communities we work in. But there's something really remarkable about seeing that ideal at work in a community where there are no grades and no graduation, where the congregation is not just 18-22 year-olds with high entrance exam scores, and where no one gets kicked out for failure to live up to the ideals of the place.

Last night we celebrated Christmas with hymns in two languages.

My wife came home a hour or so after she left this morning. I don't worry so much about her sudden comings and goings as I once did. She gets calls late at night from broken-hearted families watching their beloved die in our hospitals. Will she come and pray with them? Will she come hold their hands for a little while, and be the vicarious presence of the whole church as they suffer? Will she anoint the sick as a reminder of our shared hope for well-being for all people? Will she come to the jail to talk with the kid who has just been arrested, or to sit with his frightened parents? Will she come to the nursing home where they're wondering if this is the last holiday a grandparent will see?

Yes, she will. This is her calling, the work she has been ordained to do. It is the work of love, and I love her for it.

As she walked in the door, I was going to greet her when her phone rang again. I recognized from her conversation that it is a parishioner with memory problems who calls her almost every day to ask the same questions. Sometimes it seems he has been drinking; most of the time it seems he is lonely and afraid. I knew my greeting could wait, and as she patiently listened to her parishioner, I joined her in silent prayer, thanking God for the kindness she shows and represents, a visible sign of the ideal of our community. She cheerfully wished him a Merry Christmas. I think she was glad he knew what day it was.

I don't know how she does it, but she makes me want to keep trying.

One of her parishioners was coming down from a bad high in a bad way. The police were on the scene, and the whole family was understandably distressed.

I don't know many details, because as a priest she has to keep confidences. All I know is that her parishioners were asking for her to come and help before things got out of hand.

I don't know many details, because as a priest she has to keep confidences. All I know is that her parishioners were asking for her to come and help before things got out of hand.Which raises the question, "How can a minister possibly help?" She hasn't got a badge or a gun, so she can't arrest people and lock them up; she doesn't have a medical license, so she can't prescribe medications; she isn't a judge who can order someone to be placed in protective custody.

All she can do is be present with those who are suffering. She can listen to those to whom no one else will listen. She can pray with them, helping to connect those who are suffering with words to express that suffering. She can deliver the sacrament, a visible and outward sign of indelible connection to a bigger community, reminding the lonely that they are not alone.

She quickly got out of her pajamas, put on a black shirt and her clerical collar, and picked up her Book of Common Prayer. I kissed her before she went out the door, aware that she was going to a home where there was a troubled family, a belligerent drug user, and eight armed men charged with upholding the law. Oh, boy. "Do you want some company?" I asked, knowing there wasn't much I could offer besides that. She said she'd be fine.

As she left, and the kids continued to examine their gifts, I sat and silently prayed (reluctantly, as always), joining her in her work in that small way.

I admit that I do not like church. I can think of far pleasanter ways to spend my Sunday morning than leaving my house to stand, and sit, and kneel with a hundred relative strangers.

But this is one thing I love about churches: this deeply democratic commitment to including everyone in the community. No one is to be left out. No one gets more bread or more wine at the altar. Everyone who needs solace, or penance, or forgiveness, or company, may have it.

The Book Of The Acts Of The Apostles, the fifth book of the Greek testament, tells the story of the early church as a place where people who needed food or money or other kinds of sustenance could come and find them. Early on in that book we even see the story of how the church made a special office for people whose job it would be to oversee the equitable distribution of food to the poor.

I think highly of my own profession of teaching, because I think it serves a high social good. But I teach in a small, selective liberal arts college. Most of the people I serve have their lives pretty much together. In general, they can pay their bills, they don't have huge drug or legal issues, they have supportive communities, they can think and write well. Yes, most of them struggle with money and other things, but they keep their heads above water, and their futures are bright.

My wife, on the other hand, has a much broader "clientele." She serves the congregations at our cathedral and several other parishes. Her congregants range from the powerful and wealthy to the poorest of the poor. Here in South Dakota more than half our diocese are Native Americans, and many more are refugees from conflicts in east Africa. Ethnically, racially, economically, liturgically, and politically, this is a diverse group.

And again, it is a group where everyone is - or at least ought to be - welcome.

The church has always failed to live up to its ideals. I don't dispute that. Show me an institution that has good ideals and that always lives up to them, and I'll readily tip my hat to it. What I love in the church is that it has these ideals and it has daily, weekly, and annual rituals by which we remind ourselves what those ideals are. We screw them up, we distort and bastardize them, we even sell them to high bidders from time to time when we lose our heads and our hearts. But then we remind ourselves that we should not. And we have institutions and rituals of returning to the path we've departed from.

We will probably always get it wrong. I'm okay with that, as long as we keep turning back towards what is right, as long as we maintain these traditions and rituals of self-examination and self-correction. And as long as we cherish this ideal of welcoming everyone, absolutely everyone. I don't mean just saying we welcome everyone, but I mean doing it.

Again, I work at a small college. Colleges are places where we all talk a good game about being welcoming, and for the most part, we manage to practice what we preach, given the communities we work in. But there's something really remarkable about seeing that ideal at work in a community where there are no grades and no graduation, where the congregation is not just 18-22 year-olds with high entrance exam scores, and where no one gets kicked out for failure to live up to the ideals of the place.

Last night we celebrated Christmas with hymns in two languages.

Hanhepi wakan kin!That's the second verse of "Silent Night, Holy Night," from the Dakota Episcopal hymnal. We sing the doxology in Dakota, and I'm happy to say that most of the white folks at several congregations in the area have it memorized in Dakota. These are small things, but they might also be big things. If the baby Christ was the Word incarnate, surely little words can make a big difference.

Wonahon wotanin

Mahpiyata wowitan,

On Wakantanka yatanpi.

Christ Wanikiya hi!

My wife came home a hour or so after she left this morning. I don't worry so much about her sudden comings and goings as I once did. She gets calls late at night from broken-hearted families watching their beloved die in our hospitals. Will she come and pray with them? Will she come hold their hands for a little while, and be the vicarious presence of the whole church as they suffer? Will she anoint the sick as a reminder of our shared hope for well-being for all people? Will she come to the jail to talk with the kid who has just been arrested, or to sit with his frightened parents? Will she come to the nursing home where they're wondering if this is the last holiday a grandparent will see?

Yes, she will. This is her calling, the work she has been ordained to do. It is the work of love, and I love her for it.

As she walked in the door, I was going to greet her when her phone rang again. I recognized from her conversation that it is a parishioner with memory problems who calls her almost every day to ask the same questions. Sometimes it seems he has been drinking; most of the time it seems he is lonely and afraid. I knew my greeting could wait, and as she patiently listened to her parishioner, I joined her in silent prayer, thanking God for the kindness she shows and represents, a visible sign of the ideal of our community. She cheerfully wished him a Merry Christmas. I think she was glad he knew what day it was.

I don't know how she does it, but she makes me want to keep trying.

∞

One thing that made the sermon especially strong was its open-endedness: our priest didn't try to apply the sermon to any one social problem, as he could have. Instead, he invited all his listeners to consider whether we'd be willing to have big love remake our lives. In other words, rather than making this into a doctrinal roll-call or a chance to affirm that we all believe the same thing and then move on, unchanged, we were invited to consider, in quiet self-examination, whether we were willing to let love rule in our lives.

One thing that made the sermon especially strong was its open-endedness: our priest didn't try to apply the sermon to any one social problem, as he could have. Instead, he invited all his listeners to consider whether we'd be willing to have big love remake our lives. In other words, rather than making this into a doctrinal roll-call or a chance to affirm that we all believe the same thing and then move on, unchanged, we were invited to consider, in quiet self-examination, whether we were willing to let love rule in our lives.

Part of me really doesn't like church. There's so much about it that bores me, and I usually like sermons least of all. And when I'm not bored, I'm often surrounded by people I don't know very well, shaking my hand and passing a sign of peace. It's an introvert-germophobe's introduction to the doctrine of hell, I guess, so it does serve that theological purpose. I'd prefer a quick nod, some formal bowing, a lot of incense and some well-tuned bells, but you can't always get what you want.

Part of me really doesn't like church. There's so much about it that bores me, and I usually like sermons least of all. And when I'm not bored, I'm often surrounded by people I don't know very well, shaking my hand and passing a sign of peace. It's an introvert-germophobe's introduction to the doctrine of hell, I guess, so it does serve that theological purpose. I'd prefer a quick nod, some formal bowing, a lot of incense and some well-tuned bells, but you can't always get what you want.

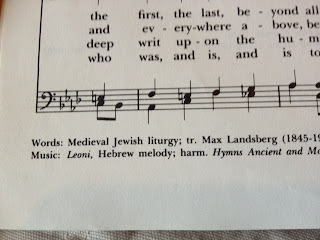

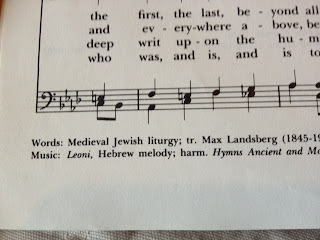

This morning was a pretty good morning. Not only did I hear that excellent sermon that will provide food for thought all week, we also sang a hymn that was translated from a Medieval Hebrew liturgy. Good hymnals and prayerbooks can be bouquets of the choicest flowers of religious poetry. The Book of Common Prayer has often rescued my anguished mind when it cannot find words. Often, when I sing hymns to the room-filling sound of a well-played pipe organ, I find myself wondering how people who do not have a congregation to sing with find opportunities to sing with others. That probably sounds judgmental, but I don't mean it to. I just wish there were more songs sung by people in our daily lives. I suspect the near-universal ownership of iPods is a result of the vanishing tradition of singing together.

This morning was a pretty good morning. Not only did I hear that excellent sermon that will provide food for thought all week, we also sang a hymn that was translated from a Medieval Hebrew liturgy. Good hymnals and prayerbooks can be bouquets of the choicest flowers of religious poetry. The Book of Common Prayer has often rescued my anguished mind when it cannot find words. Often, when I sing hymns to the room-filling sound of a well-played pipe organ, I find myself wondering how people who do not have a congregation to sing with find opportunities to sing with others. That probably sounds judgmental, but I don't mean it to. I just wish there were more songs sung by people in our daily lives. I suspect the near-universal ownership of iPods is a result of the vanishing tradition of singing together.

Can I Ask Questions In Church?

Today I heard a thoughtful, thought-provoking sermon about St Paul's Epistle to Philemon. The heart of it was this: Paul urged Philemon not to claim his legal right, but to lay aside his rights for the sake of the big love that wants to remodel his whole life.

Nobody in their right mind wants that.

Which is why Paul describes that big love elsewhere as foolishness to Greeks - and, he might have added, to anyone else who takes reason seriously.

After all, it's a little bit crazy to lay aside your legal rights for the sake of others. In Philemon's case, Paul was asking him to:

*****

One thing that made the sermon especially strong was its open-endedness: our priest didn't try to apply the sermon to any one social problem, as he could have. Instead, he invited all his listeners to consider whether we'd be willing to have big love remake our lives. In other words, rather than making this into a doctrinal roll-call or a chance to affirm that we all believe the same thing and then move on, unchanged, we were invited to consider, in quiet self-examination, whether we were willing to let love rule in our lives.

One thing that made the sermon especially strong was its open-endedness: our priest didn't try to apply the sermon to any one social problem, as he could have. Instead, he invited all his listeners to consider whether we'd be willing to have big love remake our lives. In other words, rather than making this into a doctrinal roll-call or a chance to affirm that we all believe the same thing and then move on, unchanged, we were invited to consider, in quiet self-examination, whether we were willing to let love rule in our lives.

This is like Mary's approach in John's Gospel, when she tells Jesus "They have no more wine," then tells the servants, "Do whatever he says." She knows enough to know that she doesn't know all the answers. I think our priest was saying something similar today: he doesn't know all the answers, but he's committed to big love, and was inviting us to consider whether we also share that confidence.

To put it differently, he left us with a question to mull over for the week.

Which is often far more helpful than being left with an answer.

*****

Part of me really doesn't like church. There's so much about it that bores me, and I usually like sermons least of all. And when I'm not bored, I'm often surrounded by people I don't know very well, shaking my hand and passing a sign of peace. It's an introvert-germophobe's introduction to the doctrine of hell, I guess, so it does serve that theological purpose. I'd prefer a quick nod, some formal bowing, a lot of incense and some well-tuned bells, but you can't always get what you want.

Part of me really doesn't like church. There's so much about it that bores me, and I usually like sermons least of all. And when I'm not bored, I'm often surrounded by people I don't know very well, shaking my hand and passing a sign of peace. It's an introvert-germophobe's introduction to the doctrine of hell, I guess, so it does serve that theological purpose. I'd prefer a quick nod, some formal bowing, a lot of incense and some well-tuned bells, but you can't always get what you want.

But you do often get what you need, and I think of church the way I think of prayer, or aerobic exercise, or dietary fiber: I need them. Even, and perhaps especially, when I don't want them. And when they are a part of my life, my life feels more whole.

This can be hard to explain to others, so I understand if you think I go to church because it makes me feel good, or because my culture has made it hard for me to think of doing otherwise, or because I feel guilty when I don't go.

I actually feel pretty good when I don't go to church, just like I feel pretty good when I decide to write a blog post instead of going on that four-mile run I had planned.

And so often, when I attend churches, I hear or see things I wish I hadn't heard or seen. These congregations founded on the worship of big love can become gardens overrun by the weeds of uncharitable hearts; some "hymns" I hear are schmaltzy or foolish, or unintentionally (I hope!) promote slavish and unkind ideas about race or gender. At times like that, I'm tempted to give up on "organized" religion altogether.

*****

This morning was a pretty good morning. Not only did I hear that excellent sermon that will provide food for thought all week, we also sang a hymn that was translated from a Medieval Hebrew liturgy. Good hymnals and prayerbooks can be bouquets of the choicest flowers of religious poetry. The Book of Common Prayer has often rescued my anguished mind when it cannot find words. Often, when I sing hymns to the room-filling sound of a well-played pipe organ, I find myself wondering how people who do not have a congregation to sing with find opportunities to sing with others. That probably sounds judgmental, but I don't mean it to. I just wish there were more songs sung by people in our daily lives. I suspect the near-universal ownership of iPods is a result of the vanishing tradition of singing together.

This morning was a pretty good morning. Not only did I hear that excellent sermon that will provide food for thought all week, we also sang a hymn that was translated from a Medieval Hebrew liturgy. Good hymnals and prayerbooks can be bouquets of the choicest flowers of religious poetry. The Book of Common Prayer has often rescued my anguished mind when it cannot find words. Often, when I sing hymns to the room-filling sound of a well-played pipe organ, I find myself wondering how people who do not have a congregation to sing with find opportunities to sing with others. That probably sounds judgmental, but I don't mean it to. I just wish there were more songs sung by people in our daily lives. I suspect the near-universal ownership of iPods is a result of the vanishing tradition of singing together.

When I came home I saw that a friend had tagged me in a post on Facebook, where she shared this article about the importance of continuing to ask big questions. To which I say "amen."

The article raises just this question of whether a decline in attendance at religious services decreases the places in which can we ask big questions:

The article raises just this question of whether a decline in attendance at religious services decreases the places in which can we ask big questions:

"“For anyone who goes to church, these are the questions they are essentially grappling with via their faith,” said Brooks. Indeed, a measurable drop in religious affiliation and attendance at houses of worship may be a factor in the decline of a culture of inquiry and conversation."

I don't know if that's true, and I don't want to claim that the sky is falling because the pews aren't full. But I do find that sitting in the pew helps me, and I think it could be more helpful to more people if there were more sermons like the one I heard today. It's good to ask questions together, and to let the questions do their work.

So I hope that more of us who think that meeting together to pray and sing and reflect on what we believe is a worthwhile practice will do as our priest did this morning, inviting others to turn with him to reflect on the big questions, and the big ideas, and the big love, that - in my case, at least - can keep us from living unexamined lives.

∞

Written On The Skin

One of the peculiar things about teaching Greek and knowing several other ancient languages is that people often come to me seeking help with tattoos.

A few years ago a student named Brian came to me and asked "How do you say 'Suck Less' in Greek?" Apparently this was a phrase that his running coach said to his team to inspire them to run better.

As crude as the phrase is, I was intrigued by the problem of translation. "In order to translate the phrase I'd have to know what you mean by it," I replied. I spent a little while explaining how it would be possible to say, for instance, that an infant should nurse less; or that one should inhale less strongly. Or, if you pursue the more colloquial usage of the verb "suck," you might decide that it refers to poor behavior or - ahem - to a kind of erotic pleasure-giving in which the giver is thought to be demeaned by the giving.

Eventually I made the case that if you want to say it in Classical Greek, it would make sense to say it in a way that attended to the use of words in that language, and pointed him to Plutarch's Sayings of Spartan Women as a source of pithy sayings about living and acting strenuously. Ever since I took my first Greek class with Eve Adler at Middlebury College years ago, I've liked the phrase η ταν η επι τας, (at the link above, see #16 under "Other Spartan Women"; click on the Greek flag to see the full Greek text) which is often translated "Come back with your shield or upon it," meaning "Act virtuously in battle; either die with your weapons or win with your weapons, but do not throw them away in order to win your life at the expense of your virtue." I like the Greek phrase for its Laconian pithiness.

Of course, that one didn't quite make sense for a runner, so I showed him another from the same collection, κατα βημα της αρετης μεμνησο, or "With every step, remember [your] virtue." ("Virtue" is not a perfect translation; you could translate it as "excellence" also.)

Three years have passed since that conversation with Brian, but a few months ago he tracked me down and showed me his tattoo, which I rather like:

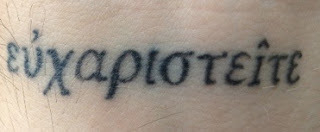

In a new twist, last year another student asked me to help him find the Greek verb "give thanks" as it appears in I Thessalonians 5.18. He didn't tell me what he planned to do with it, but when I saw him later that year at a wedding he showed me this, which he has tattooed on his wrist:

The word you see is ευχαριστειτε, related to our word "Eucharist" and the modern Greek ευχαριστω, meaning "I thank you."

I say this is a "new twist" because at least one passage in the Hebrew scriptures (Leviticus 19.28) appears to prohibit tattooing one's skin. Getting a tattoo, and in particular getting a tattoo of scripture, offers a bit of insight into one's hermeneutics. If the Gospels prohibited tattoos, I doubt many Christians would get them, but since the prohibition comes in the Hebrew scriptures, and since it seems to be tied to particular practices of worship or enslavement that no longer seem relevant, many young Christians are untroubled by it.

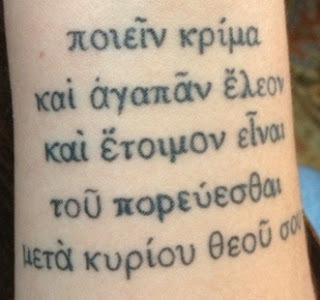

Recently one of my advisees showed me one of several tattoos she has recently acquired. This one is a longer Biblical text, from the prophet Micah, chapter 6, verse 8. I thought it interesting that she chose to get the Septuagint Greek rather than the Hebrew. She knows and translates Biblical (Koine) Greek and so I suppose she felt closer to that language. The text below means "...to do justice and to love mercy and to be ready/zealous to walk humbly with the Lord your God."

I like that verse quite a lot. If you don't know it, it begins by saying that this is what God asks of people. It's the sort of description that makes religion sound less like a burden and more like a description of a life well-lived.

I'm always reluctant to give advice about tattoos, because they're so permanent and so personal. And when I do give advice, I always want to write footnotes about regional dialects and historical and textual variants, or about the difficulties of translation. Quotes out of their native context so often seem lonely to me - such is my academic habit, of always seeing texts as living and moving and having their being* in nests and webs of other texts. Perhaps that's why I've never been inked myself, and I doubt I ever will get a "tat." I'm just not confident I've found words or an image that I'd want written on me forever. Sometimes that feels virtuous because it's prudent; other times I wonder if that's not a moral failing on my part, like I should be willing to commit to something. But I think for now I will remain uninked, and will continue to admire the commitments of my students.

* For example: I am borrowing this phrase ("live and move and have their being") from St Paul in Acts 17.28; he, in turn, appears to be borrowing it from Epimenides, who writes Εν αυτω γαρ ζωμεν και κινουμεθα και εσμεν. The phrase winds up being used in a number of other places, having been so eloquently translated into English by the King James Version of the Bible. See, for example, its use in the Book of Common Prayer, and in the first line of the hymn "We Come O Christ To Thee."

A few years ago a student named Brian came to me and asked "How do you say 'Suck Less' in Greek?" Apparently this was a phrase that his running coach said to his team to inspire them to run better.

As crude as the phrase is, I was intrigued by the problem of translation. "In order to translate the phrase I'd have to know what you mean by it," I replied. I spent a little while explaining how it would be possible to say, for instance, that an infant should nurse less; or that one should inhale less strongly. Or, if you pursue the more colloquial usage of the verb "suck," you might decide that it refers to poor behavior or - ahem - to a kind of erotic pleasure-giving in which the giver is thought to be demeaned by the giving.

Eventually I made the case that if you want to say it in Classical Greek, it would make sense to say it in a way that attended to the use of words in that language, and pointed him to Plutarch's Sayings of Spartan Women as a source of pithy sayings about living and acting strenuously. Ever since I took my first Greek class with Eve Adler at Middlebury College years ago, I've liked the phrase η ταν η επι τας, (at the link above, see #16 under "Other Spartan Women"; click on the Greek flag to see the full Greek text) which is often translated "Come back with your shield or upon it," meaning "Act virtuously in battle; either die with your weapons or win with your weapons, but do not throw them away in order to win your life at the expense of your virtue." I like the Greek phrase for its Laconian pithiness.

Of course, that one didn't quite make sense for a runner, so I showed him another from the same collection, κατα βημα της αρετης μεμνησο, or "With every step, remember [your] virtue." ("Virtue" is not a perfect translation; you could translate it as "excellence" also.)

Three years have passed since that conversation with Brian, but a few months ago he tracked me down and showed me his tattoo, which I rather like:

In a new twist, last year another student asked me to help him find the Greek verb "give thanks" as it appears in I Thessalonians 5.18. He didn't tell me what he planned to do with it, but when I saw him later that year at a wedding he showed me this, which he has tattooed on his wrist:

The word you see is ευχαριστειτε, related to our word "Eucharist" and the modern Greek ευχαριστω, meaning "I thank you."

I say this is a "new twist" because at least one passage in the Hebrew scriptures (Leviticus 19.28) appears to prohibit tattooing one's skin. Getting a tattoo, and in particular getting a tattoo of scripture, offers a bit of insight into one's hermeneutics. If the Gospels prohibited tattoos, I doubt many Christians would get them, but since the prohibition comes in the Hebrew scriptures, and since it seems to be tied to particular practices of worship or enslavement that no longer seem relevant, many young Christians are untroubled by it.

Recently one of my advisees showed me one of several tattoos she has recently acquired. This one is a longer Biblical text, from the prophet Micah, chapter 6, verse 8. I thought it interesting that she chose to get the Septuagint Greek rather than the Hebrew. She knows and translates Biblical (Koine) Greek and so I suppose she felt closer to that language. The text below means "...to do justice and to love mercy and to be ready/zealous to walk humbly with the Lord your God."

I like that verse quite a lot. If you don't know it, it begins by saying that this is what God asks of people. It's the sort of description that makes religion sound less like a burden and more like a description of a life well-lived.

I'm always reluctant to give advice about tattoos, because they're so permanent and so personal. And when I do give advice, I always want to write footnotes about regional dialects and historical and textual variants, or about the difficulties of translation. Quotes out of their native context so often seem lonely to me - such is my academic habit, of always seeing texts as living and moving and having their being* in nests and webs of other texts. Perhaps that's why I've never been inked myself, and I doubt I ever will get a "tat." I'm just not confident I've found words or an image that I'd want written on me forever. Sometimes that feels virtuous because it's prudent; other times I wonder if that's not a moral failing on my part, like I should be willing to commit to something. But I think for now I will remain uninked, and will continue to admire the commitments of my students.

*****

* For example: I am borrowing this phrase ("live and move and have their being") from St Paul in Acts 17.28; he, in turn, appears to be borrowing it from Epimenides, who writes Εν αυτω γαρ ζωμεν και κινουμεθα και εσμεν. The phrase winds up being used in a number of other places, having been so eloquently translated into English by the King James Version of the Bible. See, for example, its use in the Book of Common Prayer, and in the first line of the hymn "We Come O Christ To Thee."

*****

Update: a week or so after posting this I ran into the mother of one of the people whose tattoos are shown above. She thanked me, though I am not sure whether she was thanking me for helping her son get a tattoo, or for helping him to get the grammar right.

∞

Happy Praise

I recently read this line in the Book of Common Prayer, in the BCP's translation of the Phos Hilaron prayer. The Phos Hilaron is one of the oldest Christian hymns:

I'm preparing a scholarly article on St Paul's response to Epicurean philosophy, one I hope to publish soon. For now, I will summarize one of its points: Christians and Epicureans disagree about the imperturbability of the divine (Christians disagree among themselves about this as well) but they agree that if something can't be praised with gladness at least sometimes, then it's probably not worth praising at all.

This is not just abstract philosophy or theology; it matters for all of life. We are all always engaged in worship, as David Foster Wallace once said. We don't get much choice about that. We do have a choice about what we worship - what we ascribe worth to. We do that all the time when we vote, when we spend and invest our money, when we decide what our laws should be and what our children should learn. We constantly make decisions about ends that should be pursued, and these are all acts of worship.

** Diogenes Laertius, 10.139; from The Epicurus Reader, Brad Inwood and Lloyd Gerson, translators. (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1994) p. 32.

"Thou art worthy at all times to be praised by happy voices, O Son of God, O Giver of Life..."It needn't be translated that way, by the way. It could be translated as "reverent voices" or "opportune voices." I like this translation, though. The sentiment is positively Epicurean. Consider the opening line of Epicurus's Kuriai Doxai*:

"What is blessed and indestructible has no troubles itself, nor does it give trouble to anyone else..."**In Epicurus's view, a god that is petulant or demanding is a god that is needy and manipulative. Such gods may force us to make sacrifices, but they won't earn our praise so much as our derision and scorn. A god worthy of the name is one that needs and demands nothing for itself.

I'm preparing a scholarly article on St Paul's response to Epicurean philosophy, one I hope to publish soon. For now, I will summarize one of its points: Christians and Epicureans disagree about the imperturbability of the divine (Christians disagree among themselves about this as well) but they agree that if something can't be praised with gladness at least sometimes, then it's probably not worth praising at all.

This is not just abstract philosophy or theology; it matters for all of life. We are all always engaged in worship, as David Foster Wallace once said. We don't get much choice about that. We do have a choice about what we worship - what we ascribe worth to. We do that all the time when we vote, when we spend and invest our money, when we decide what our laws should be and what our children should learn. We constantly make decisions about ends that should be pursued, and these are all acts of worship.

*****

* We usually translate this "Principal Doctrines." The word "kuriai" or "kurios" means "principal" and has the same breadth of resonances and meanings as that word: princely, first and foremost, primary, authoritative. The word "doxai" or "doxa" has a similar breadth of meanings, ranging from opinion or estimation to reputation and even glory. The Epicurean title kuriai doxai would have sounded familiar to early Greek-speaking Christians, for whom it would have sounded like "Lordly glories." The familiar prayer Kyrie eleison is related to the word kurios or kyrios. ** Diogenes Laertius, 10.139; from The Epicurus Reader, Brad Inwood and Lloyd Gerson, translators. (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1994) p. 32.

∞

Charles Peirce's Version Of The "Lord's Prayer"

Charles Peirce's writings frequently touch on religious topics. As Douglas Anderson, Michael Raposa, Hermann Deuser and others (myself included) have argued this is not accidental but integral to his philosophy.

Throughout his life he wrote on prayer, usually tersely, though occasionally he wrote at length, as when he proposed some changes to the Episcopal Church's Book of Common Prayer based on his semeiotic theory.

Here is one piece from his journal, written while he was a student at Harvard in 1859. It appears to be a re-writing of the Lord's Prayer:

(This is from MS 891, “Private Thoughts,” number XLVI. Peirce's writings include his vast unpublished writings, mostly held at Harvard, with copies at IUPUI and Texas Tech)

Throughout his life he wrote on prayer, usually tersely, though occasionally he wrote at length, as when he proposed some changes to the Episcopal Church's Book of Common Prayer based on his semeiotic theory.

Here is one piece from his journal, written while he was a student at Harvard in 1859. It appears to be a re-writing of the Lord's Prayer:

"I pray thee, O Father, to help me regard my innate ideas as objectively valid. I would like to live as purely in accordance with thy laws as inert matter does with nature's. May I, at last, have no thoughts but thine, no wishes but thine, no will but thine. Grant me, O God, health, valor, and strength. Forgive the misuse, pray of thy former good gifts, as I do the ingratitude of my friends. Pity my weakness and deliver me, O Lord; deliver me and support me."

(This is from MS 891, “Private Thoughts,” number XLVI. Peirce's writings include his vast unpublished writings, mostly held at Harvard, with copies at IUPUI and Texas Tech)

∞

I wonder, though, if the people who make this kind of claim are trying to understand prayer as a kind of incantation. That is, it seems like they are saying that the best way to examine prayer is to study its effectiveness, by which they mean that some people should ask God for something and then we will measure the frequency with which those prayers are "answered."

Now, I'm no expert on prayer. And I know that any discussion of prayer is going to get sticky. But I think this kind of effectiveness study is misguided. I don't think we should think of prayer as words we say in order to make God do things that God would not otherwise do. If it were, that would make prayer into a kind of magic, or it would turn God into a kind of technology, or both.

When I read the prayers in the Anglican Book of Common Prayer, or when I listen to or read others' prayers, I see something else: the people who pray seem to have the expectation that God will do what God will do, not what they want God to do. In a way, this makes sense: if God is personal, then God is not to be dominated or pushed around any more than we are. It seems like most of the prayers I've read sound like requests and arguments and complaints and even like words spoken in love. Even when (as in the Book of Job) people chastise God for seeming not to act, or when they rebuke or forgive God for not having acted, there seems to be a sense that God is a person, not a tool.

I think that if we were to look to some of the great works of prayer - the works of the mystics in any tradition, for instance - or even if we were to ask ordinary people why they pray, we would find that their concern is not with whether prayer makes miracles happen but with the way in which prayer manifests and nurtures their relationship with the divine. I don't really know how to judge that sort of claim, and I often just listen to it in wonder. But I'm pretty sure that if we were to attempt to measure the "effectiveness" of that prayer, we would wind up ignoring or doing violence to the claim that what matters most in prayer is the conversation and the relationship.

Is Prayer "Effective"?

I recently read a short essay that described prayer as something that should best be studied by the physical sciences. This claim has been made for quite a long time, and I think there may be some truth to it.

I wonder, though, if the people who make this kind of claim are trying to understand prayer as a kind of incantation. That is, it seems like they are saying that the best way to examine prayer is to study its effectiveness, by which they mean that some people should ask God for something and then we will measure the frequency with which those prayers are "answered."