books

- Henry Bugbee, The Inward Morning. Don't try to read this book quickly, and if you're not prepared to do the hard work of thinking, move on and read something else. But if you're willing to read slowly and thoughtfully, this book can change your life. Bugbee was a philosophy professor and an angler.

- Henry David Thoreau, A Week On The Concord and Merrimack Rivers; The Maine Woods. Thoreau was an occasional angler, and an observer of anglers.

- Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac and the title essay in The River Of The Mother Of God, about unknown places. Leopold only writes a little about fish and fishing, but those occasional sentences about angling tend to be shot through with insight.

- John Muir, Nature Writings.

- John Steinbeck, Log From The Sea of Cortez. An apology for curiosity, in narrative form. One of my favorite books.

- Paul Errington, The Red Gods Call. Not brilliant writing, but a fascinating set of memoirs from a professor of biology who put himself through college as a trapper, and about how the Big Sioux River in South Dakota was his first real schoolroom. He talks a good deal about hunting and fishing and what he learned through encounters with animals.

- Kathleen Dean Moore, The Pine Island Paradox. Moore is an environmental philosopher who writes winsomely ans insightfully about what nature has meant to her family.

- Nick Lyons. Nick very kindly wrote the foreword to my book, and when I first got in touch with him about this I discovered he and I had lived only a few miles from each other in the Catskill Mountains for years. Sadly, by the time I discovered this I'd already moved away, and he was packing up to move to a new home, too. We both love the miles of small trout streams of those mountains, though. Nick has been a prolific writer and he has promoted a lot of great writing through his lifelong work as a publisher as well. Nick has a new book, Fishing Stories, just published in 2014.

- Norman Maclean, A River Runs Through It

- Ernest Hemingway, especially "Big Two-Hearted River" and the other Nick Adams stories

- James Prosek. Several books, including Trout: An Illustrated History; Early Love And Brook Trout; and Joe And Me: An Education In Fishing And Friendship

- Ted Leeson, The Habit Of Rivers

- Kurt Fausch’s new book, For The Love Of Rivers: A Scientist’s Journey. Brilliant writing by one of the world's leading trout biologists.

- Craig Nova, Brook Trout and the Writing Life. I also like his novels, and will recommend The Constant Heart.

- Christopher Camuto, who writes frequently for Trout Unlimited's journal, Trout.

- Ian Frazier, The Fish's Eye.

- Douglas Thompson, The Quest For The Golden Trout

- Izaak Walton, The Compleat Angler

- Dame Juliana Berners, The Boke Of St Albans, later editions of which contain A Treatyse of Fysshynge with an Angle, possibly authored by someone else.

- Nick Karas, Brook Trout (a nice collection of short works about brook trout, including some of my favorite stories)

- Lee Wulff

- Lefty Kreh

- John Gierach. Gierach has written a lot about angling, so it's not surprising that so many people mention him to me. Many of those mentions are positive, but some anglers mention his name with disgust. I haven't read much of his work, so I can't yet say why.

- David James Duncan, The River Why. This is a fun novel set in the Northwest, but it reminds me of the New Haven River in Vermont: there are some long dry stretches one has to plod through, but repeatedly one comes to depths that make the flatter, shallower parts worthwhile.

- Thomas McGuane, The Longest Silence.

- Bill McMillan

- Roderick Haig-Brown

- Mike Valla, The Founding Flies

- Michael Patrick O’Farrell, A Passion For Trout: The Flies And The Methods

- Peter Reilly, Lakes and Rivers of Ireland

- Derek Grzelewski, The Trout Diaries: A Year of Fly-fishing In New Zealand and The Trout Bohemia: Fly-Fishing Travels In New Zealand

- Eeva-Kaarina Aronen, Die Lachsfischerin. A novel set in Finland, about fly-fishing and fly-tying in the 18th century. The title translates as “The Salmon Fisherwoman”

- Ian Colin James, Fumbling With A Fly Rod (Scotland)

- Zane Grey, Tales of the Angler’s Eldorado: New Zealand

- Leslie Leyland Fields, Surviving the Island of Grace; and Hooked! Fields and her family are commercial fishers in Alaska, and her writing comes recommended to me from a number of sources.

- Sheridan Anderson, The Curtis Creek Manifesto

- Harry Middleton, The Earth Is Enough: Growing Up In A World Of Fly-fishing, Trout, And Old Men (Memoir)

- Paul Schullery, Royal Coachman: The Lore And Legends of Fly-fishing

- Gordon MacQuarrie

- Patrick McManus

- Vince Marinaro, The Game of Nods

- Rich Tosches, Zipping My Fly

- Robert Lee, Guiding Elliott

- Peter Heller, The Dog Stars (novel)

- Paul Quinnett, Pavlov’s Trout

- Dana S. Lamb Where The Pools Are Bright And Deep; Bright Salmon and Brown Trout

- John Shewey, Mastering The Spring Creeks

- Ernest Schweibert, Death of a Riverkeeper; A River For Christmas

- Richard Louv, Fly-fishing for Sharks: An Angler’s Journey Across America

- John Voelker’s short story “Murder”

- Dave Ames, A Good Life Wasted, Or 20 Years As A Fishing Guide

- Craig Childs, The Animal Dialogues, especially the chapter “Rainbow Trout”

- Randy Nelson, Poachers, Polluters, and Politics: A Fishery Officer’s Career

- Anders Halverson, An Entirely Synthetic Fish: How Rainbow Trout Beguiled America And Overran The World

- Thomas McGuane, A Life In Fishing

- Bob White

- Robert Ruark

- Tom Meade

- Hank Patterson

- Richard Russo, Straight Man. This is one that has been recommended to me so many times by so many people I finally bought it and read it. If you work in a small college humanities department, trust me: you'll feel at home in this book.

- J. M. Coetzee, Elizabeth Costello. This is another that was recommended to me. It takes the form of a series of lectures delivered by a novelist, with very little framing around each lecture. The lectures stand alone, but all together they give the picture of an artist at work trying to figure out what exactly she is doing, what she believes, and why. Coetzee is really a philosophical novelist, and he does a remarkable job of engaging directly with figures like Descartes and Kant and Peter Singer.

- Dave Eggers, How We Are Hungry. Eggers' short stories are like David Foster Wallace's, but less frenetic and wild and so a little easier to read. I love the genre, and I'm always fascinated by people like Eggers and Wallace who explore its edges. I don't love this book, but it has kept my attention as a kind of intellectual exercise, and it is like a garden filled with tiny blossoms that delight the eye when you slow down and look closely.

- Matthew Dickerson, The Rood And The Torc. Dickerson is a friend of mine and my co-author, so there's my disclosure. Now let me say this about Dickerson: there are good reasons why he's my friend and my co-author, and this book illustrates some of them. He's a natural, easy storyteller who makes you glad you kept turning the pages. His prose is light, disappearing from the eye, easily replaced with a mental image of the place and the characters. This is one of several novels he has written about the peripheries of Beowulf, a beautiful story about poetry, songs, medieval Europe, and the cost of making the right choices. Reading this book was the first time I felt like I could see medieval life, not just read about it. Homes and hearths come alive with smoke and roasting meat and moving songs; the Frisian landscape and the rolling sea and the smell of cowherds seem to lift off the pages and into my imagination as I read it. John Wilson is right: this is "a splendid historical novel." Dickerson is brilliant, and so is his prose.

-

Hunter S. Thompson, Screwjack. This is the book Carlos Castaneda would have written if he'd admitted he was writing fiction. You feel the intoxication, and you believe it.

- Herman Melville, Moby Dick. This is one of those books that everyone knows and nearly nobody reads. It is long, and full of words. Lots and lots of words. But wow. It is one of those rare books that gives me the sense that every sentence was the child of long and serious reflection. Reading this was like taking a really good class. Naturally, I bought myself a "What Would Queequeg Do?" t-shirt to mark this milestone in my life. You can get yours here.

- Nathaniel Hawthorne, Mosses From An Old Manse. And this is like Melville. You read it because at the end, you discover that what seemed to be a simple story about a simple thing makes you understand your world a lot better.

- John Steinbeck, The Moon Is Down. I love Steinbeck, so I bought this book not knowing a thing about it. Turns out Steinbeck wrote it as a propaganda piece. He wanted to give a picture of what it would look like to live in, say, Norway or Denmark under Nazi rule, and how that occupation could lead to resistance. What I love about Steinbeck is, more than anything, his desire to portray people with sympathy. The Nazis in his book are real people, believable, and even likeable. I wish we had more people able to portray our contemporary enemies with such sympathy. If we could do so, we could love them better, and I think we could better understand how to resist them. As a bonus, towards the end of the novel there is a prolonged reflection on the meaning of Plato's Apology of Socrates.

- Patrick Hicks, The Commandant of Lubizec. (Another disclosure: Hicks is also my friend.) I was pretty sure I'd read all I needed to read about the Holocaust. I grew up with survivors. I've read all the usual books, I teach several in my classes. I didn't want to hear any more. But Hicks has done something truly remarkable in this fictionalized account of Operation Reinhard. In fact, what he's done is similar to what Steinbeck does: he has written about people with real sympathy and insight. It's a hard read because he spares us nothing, but that's precisely what makes it such a good read. Here's a short video about the book:

- Virginia Woolf, Mrs. Dalloway. (Mixed feelings about this one. My mind enjoyed it more than my aesthetic sense did, if that makes sense.)

- John Steinbeck, Cannery Row and Of Mice and Men. (I discovered Steinbeck late in life, thanks to a friend's recommendation. I've also recently read his Log From The Sea of Cortez and Travels With Charley In Search Of America. I think these two will forever shape me as a writer.)

- Graham Greene, Our Man In Havana, The Quiet American, The Honorary Consul, Travels With My Aunt, The Power And The Glory. (I will let the number of titles speak for itself.)

- Alan Paton, Cry, The Beloved Country. (I was surprised by how contemporary this old book felt, and by how relevant to America an African book could feel.)

- The Táin. Because I have a thing for reading really old books, and this is one of the oldest from Europe.

- China Miéville, Kraken. (London. Magical realism. Bizarre and witty.)

- J. Mark Bertrand, Back On Murder (I don't read many detective novels, but I really enjoy Bertrand's prose.)

- Cormac McCarthy, The Road. (The final lines spoke to my salvelinus fontinalis -loving heart.)

- David James Duncan, The River Why (I've re-read this one a few times. If you like trout and philosophy, you might like this book.)

- Mary Karr, Lit. (Third in a series of memoirs. Some of the best storytelling I've read in a long time. Brilliant insights into addiction, love, and prayer.)

∞

Books Worth Reading

Occasionally I post on this blog a list of books I’ve been reading. It’s a way of sharing what I’ve learned, and that process of reviewing what I’ve read helps me to deepen my memory.

This post will be a little different. At the end I’ll share some new books I’ve been reading recently, but I’m going to start with some older books.

Three Older Books

China in Ten Words (Yu Hua, 2012; Allan H. Barr, translator) This is not very old, but it gives a history of some of the ideas that shape modern China. Each chapter considers one word and the way it exemplifies or illustrates something important about Chinese culture, especially since the cultural revolution. This has helped me to understand my Chinese students better, and it gives me more insight into Chinese politics, international policy, and economics. Yu Hua is a novelist, and his stories make for smooth, inviting reading. This spring I was teaching a class with students from ten different countries. At one point, one of my students from another country asked me why American schools are so concerned with plagiarism. Most of the other international students nodded in agreement. It was a helpful reminder that our American notions of intellectual property and academic integrity are tied to our idea that we are first and foremost individual agents, and it is individuals who bear responsibility for their actions and who gain the rewards for their achievements. Whether that’s true or not is debatable, but we don’t seem to have escaped from the Cartesian notion of the radical individual, the Protestant pietism that emphasizes the fall and redemption of the individual soul, or the Jeffersonian idea that rights and happiness are expressed in the individual. Over the last fifty years, China has shifted in that direction, to be sure, but China is still deeply in touch with both its Confucian sense of community and the aftereffects of its century of revolutions.

Out of the Silent Planet (C.S. Lewis, 1938) This is Lewis’ sci-fi novel about Mars. But of course no novel is ever about Mars; mostly, novels about Mars are about this planet and its inhabitants. Along with Lewis’ essay “Religion and Rocketry” (originally published as “Will We Lose God In Outer Space?”) this novel is important because it is a subtle invitation to examination of why we want to go to Mars in the first place. For me, it is one of the most important works of the ethics of space exploration, for a number of reasons. If you want all my reasons, feel free to buy my book on C.S. Lewis. Here’s one reason: most alien-encounter stories we write begin with the assumption that the aliens are the bad guys. Lewis wants us to consider that if we find our planet has gotten too uncomfortable for us, maybe we’re not the protagonists of this story.

The Way We Live Now (Anthony Trollope, 1875) This is about the 2016 election in the U.S. — but it was written in the middle of the 19th century in the U.K. I read this back in the summer of 2016, and I thought, “Oh, D.T. is going to win the election.” I won’t say it’s prescient, because it’s not explicitly about any future event, but Trollope does a good job of showing us what motivates us, how shallow those motives can be, what we will sacrifice to achieve them, and other perils of modern political life.

I’ll end this section with three unrelated books that nevertheless seem related to me: Charles Dickens’s Bleak House; Herman Melville’s Bartleby the Scrivener; and William Faulkner’s Go Down, Moses. Two things tie these books together for me: all were recommended by friends, and all have something to do with chancery courts. I have liked Melville for a long time, and I rarely regard time spent in his prose as time wasted. Dickens and Faulkner I like far less. I read Dickens as a portrait of his time, and time in his pages is like cultural archaeology. But it’s also like listening to someone make a short story into a long one while you’re trying to get to your next appointment. Faulkner is not at all like Dickens in that regard. He condenses his ideas so much that everything needs to be unpacked. Reading Faulkner quickly is unsatisfying; reading Faulkner slowly is tiring. For different reasons, Faulkner and Dickens are both tedious reads for me. Both of them make me lose the plot, one because he’s too fast, the other because he’s too slow. But in neither case is this a flaw in the author; I’m just highlighting a difference between the way they think and the way I think. Good friends recommended them, and that matters: reading what others care about can be a work of love and of fostering mutual understanding.

Should We Still Be Reading Books?

I read a lot of books each year. Usually when I tell people how many books I read, I am met with wide-eyed disbelief, so I won’t bother to tell you how many I read in a year. Instead, I will invite you to consider the importance of books. Recently I asked a group of graduate students about their reading habits. Some said they read about a dozen books a year in addition to required reading for their classes. I thought that was pretty good, considering how busy they are. But a few told me they get all their information online, mostly in condensed form through synopses and through Twitter. I don’t disparage the value of reading quickly and of foraging in the rich banquet hall of small parcels of always-ready information that our new technologies afford us. We live in rich times, indeed. I only hope that those graduate students will supplement their diet of fast reading with some slow reading and even with some fasting for contemplation and digestion.

There are some problems with books, to be sure. For one thing, they take a long time to read, and some of that reading (as with Dickens) can be slow going. For another: they take a long time to write. A third thing: the barriers to publication mean it’s easier to find books by people with connections to publishers than books by rural writers, non-English writers, etc.

But books are durable. I started writing this blog post on my tablet, and then the battery died. That never happens with books. Books are resilient, or super-resilient. Consider the way John Steinbeck’s The Moon Is Down spread across Europe during the Second World War. We think social media are fast today, but Steinbeck’s propaganda novel spread rapidly because each time someone read it they made the decision whether to copy it, and many people copied and translated it. Decisions like that are much costlier than retweeting something you glanced at, and so they carry much more weight and value. And once a book like that is copied, it’s very hard to delete it. How many books have been written about both the danger books pose to people clinging to power? And then there’s that old question about which books you’d bring to a desert island; how many of you would choose to bring a laptop or a tablet? The salt air and heat would kill it quickly even if you had solar panels to recharge it. Books are hard to beat.

A Few Recent and Current Reads

I’ll wrap up with a few recent reads, all of which I recommend, and all of which I’ll post here with minimal commentary:

Edward F. Mooney, Excursions with Thoreau: Philosophy, Poetry, Religion. (2015) Someday I would like to write like Ed Mooney. His book on Henry Bugbee was a confirmation that it’s acceptable to write academic philosophy in a way that is both clear and readable. (James Hatley did this for me in some of his articles, too. I’m grateful to both of them for that.) Now I’m very much looking forward to Mooney’s next book, Living Philosophy in Kierkegaard, Melville, and Others: Intersections of Literature, Philosophy, and Religion.

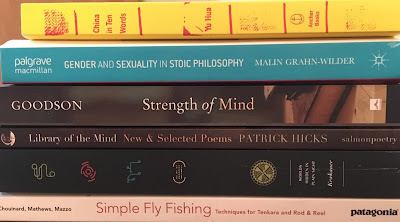

Patrick Hicks, Library of the Mind: New & Selected Poems. If you’re not reading poetry, what has gone wrong with your life? Never mind, don’t try to answer that. Instead, just read good poetry. Here’s an excellent place to start. Each page makes me slow down and collect myself again.

Malin Grahn-Wilder, Gender and Sexuality in Stoic Philosophy. I teach ancient and medieval philosophy, and I find books like this keep me sharp. The organization of the book is excellent, and so is the content. This is a nicely written history of ideas, and a useful resource for scholars.

Jacob Goodson, Strength of Mind: Courage, Hope, Freedom, Knowledge. I’ve known Jacob for a few years, and I like everything he writes. This is no exception. Jacob’s an excellent teacher with an encyclopedic mind. I have the good fortune of spending time with him in person each year, and those conversations become miniature seminars that leave me feeling refreshed and energized; he tills the soil of the mind. So you should buy this book and enjoy it. But I’m especially looking forward to his next collaboration with Brad Elliott Stone, Introducing Prophetic Pragmatism: A Dialogue on Hope, the Philosophy of Race, and the Spiritual Blues. That will be out later this year.

Evan Selinger and Brett Frischmann, Re-Engineering Humanity. This is one of a small number of books that I’ve gone back to multiple times. Selinger is worth following on Twitter for a daily dose of sharp observations on how we are letting technology race ahead of ethics. Once you’ve looked at what he posts there, you’ll find you’re either ready to check out of digital life altogether, or to go into the deep dive of this book so you can get a better handle on what to do next.

Yvon Chouinard, Craig Mathews, and Mauro Mazzo, Simple Fly Fishing: Techniques for Tenkara and Rod & Reel. Revised second edition, with paintings by James Prosek. Come for the zen-like techniques, stay for the beauty of each page, and take the time to read those small things like why Chouinard mapped several unmapped mountain routes, then burned the maps. “But standing around the campfire one day, we decided to burn our notes…There need to be a few places left on this crowded planet where ‘here be dragons’ still defines the unknown regions of maps. Then I went fishing.” If you follow me on social media, you know I write about trout and salmon. You might also know, if you pay close attention, that I love the places that the fish live, I love swimming with the fish, and I love the things and people they’re connected to. But the more I fish, the less I feel the need to fish, and the happier I am being near the fish. Tenkara rods are a very old way of being still with the fish.

David C. Krakauer, ed. Worlds Hidden In Plain Sight: The Evolving Idea of Complexity at the Santa Fe Institute 1984-2019. This is one I’m working through slowly, and I’m not reading it cover-to-cover. The organization of this book makes it one that invites a bit of flaneurism, reading deeply and thoughtfully, but in the manner of what Thoreau calls “sauntering”: not a linear, business-like drive to the finish line, but a walk without purpose other than to see what is there. This is one of the best kinds of learning. The book is, indirectly, about the importance of cross-disciplinary reading; the importance of philosophy of science for everything from understanding markets to climate change; and the helpful and constant reminder we don’t know enough about the things we quantify, even though we talk about the quantification with such authority. The book is priced at about ten bucks, but it's worth far more than that.

Is there something better than reading well-considered words? Perhaps, but all of these books have so far been well worth my while. I hope you have good books in your life as well.

This post will be a little different. At the end I’ll share some new books I’ve been reading recently, but I’m going to start with some older books.

Three Older Books

China in Ten Words (Yu Hua, 2012; Allan H. Barr, translator) This is not very old, but it gives a history of some of the ideas that shape modern China. Each chapter considers one word and the way it exemplifies or illustrates something important about Chinese culture, especially since the cultural revolution. This has helped me to understand my Chinese students better, and it gives me more insight into Chinese politics, international policy, and economics. Yu Hua is a novelist, and his stories make for smooth, inviting reading. This spring I was teaching a class with students from ten different countries. At one point, one of my students from another country asked me why American schools are so concerned with plagiarism. Most of the other international students nodded in agreement. It was a helpful reminder that our American notions of intellectual property and academic integrity are tied to our idea that we are first and foremost individual agents, and it is individuals who bear responsibility for their actions and who gain the rewards for their achievements. Whether that’s true or not is debatable, but we don’t seem to have escaped from the Cartesian notion of the radical individual, the Protestant pietism that emphasizes the fall and redemption of the individual soul, or the Jeffersonian idea that rights and happiness are expressed in the individual. Over the last fifty years, China has shifted in that direction, to be sure, but China is still deeply in touch with both its Confucian sense of community and the aftereffects of its century of revolutions.

Out of the Silent Planet (C.S. Lewis, 1938) This is Lewis’ sci-fi novel about Mars. But of course no novel is ever about Mars; mostly, novels about Mars are about this planet and its inhabitants. Along with Lewis’ essay “Religion and Rocketry” (originally published as “Will We Lose God In Outer Space?”) this novel is important because it is a subtle invitation to examination of why we want to go to Mars in the first place. For me, it is one of the most important works of the ethics of space exploration, for a number of reasons. If you want all my reasons, feel free to buy my book on C.S. Lewis. Here’s one reason: most alien-encounter stories we write begin with the assumption that the aliens are the bad guys. Lewis wants us to consider that if we find our planet has gotten too uncomfortable for us, maybe we’re not the protagonists of this story.

The Way We Live Now (Anthony Trollope, 1875) This is about the 2016 election in the U.S. — but it was written in the middle of the 19th century in the U.K. I read this back in the summer of 2016, and I thought, “Oh, D.T. is going to win the election.” I won’t say it’s prescient, because it’s not explicitly about any future event, but Trollope does a good job of showing us what motivates us, how shallow those motives can be, what we will sacrifice to achieve them, and other perils of modern political life.

I’ll end this section with three unrelated books that nevertheless seem related to me: Charles Dickens’s Bleak House; Herman Melville’s Bartleby the Scrivener; and William Faulkner’s Go Down, Moses. Two things tie these books together for me: all were recommended by friends, and all have something to do with chancery courts. I have liked Melville for a long time, and I rarely regard time spent in his prose as time wasted. Dickens and Faulkner I like far less. I read Dickens as a portrait of his time, and time in his pages is like cultural archaeology. But it’s also like listening to someone make a short story into a long one while you’re trying to get to your next appointment. Faulkner is not at all like Dickens in that regard. He condenses his ideas so much that everything needs to be unpacked. Reading Faulkner quickly is unsatisfying; reading Faulkner slowly is tiring. For different reasons, Faulkner and Dickens are both tedious reads for me. Both of them make me lose the plot, one because he’s too fast, the other because he’s too slow. But in neither case is this a flaw in the author; I’m just highlighting a difference between the way they think and the way I think. Good friends recommended them, and that matters: reading what others care about can be a work of love and of fostering mutual understanding.

Should We Still Be Reading Books?

I read a lot of books each year. Usually when I tell people how many books I read, I am met with wide-eyed disbelief, so I won’t bother to tell you how many I read in a year. Instead, I will invite you to consider the importance of books. Recently I asked a group of graduate students about their reading habits. Some said they read about a dozen books a year in addition to required reading for their classes. I thought that was pretty good, considering how busy they are. But a few told me they get all their information online, mostly in condensed form through synopses and through Twitter. I don’t disparage the value of reading quickly and of foraging in the rich banquet hall of small parcels of always-ready information that our new technologies afford us. We live in rich times, indeed. I only hope that those graduate students will supplement their diet of fast reading with some slow reading and even with some fasting for contemplation and digestion.

There are some problems with books, to be sure. For one thing, they take a long time to read, and some of that reading (as with Dickens) can be slow going. For another: they take a long time to write. A third thing: the barriers to publication mean it’s easier to find books by people with connections to publishers than books by rural writers, non-English writers, etc.

But books are durable. I started writing this blog post on my tablet, and then the battery died. That never happens with books. Books are resilient, or super-resilient. Consider the way John Steinbeck’s The Moon Is Down spread across Europe during the Second World War. We think social media are fast today, but Steinbeck’s propaganda novel spread rapidly because each time someone read it they made the decision whether to copy it, and many people copied and translated it. Decisions like that are much costlier than retweeting something you glanced at, and so they carry much more weight and value. And once a book like that is copied, it’s very hard to delete it. How many books have been written about both the danger books pose to people clinging to power? And then there’s that old question about which books you’d bring to a desert island; how many of you would choose to bring a laptop or a tablet? The salt air and heat would kill it quickly even if you had solar panels to recharge it. Books are hard to beat.

|

| Some of my recent reads. |

A Few Recent and Current Reads

I’ll wrap up with a few recent reads, all of which I recommend, and all of which I’ll post here with minimal commentary:

Edward F. Mooney, Excursions with Thoreau: Philosophy, Poetry, Religion. (2015) Someday I would like to write like Ed Mooney. His book on Henry Bugbee was a confirmation that it’s acceptable to write academic philosophy in a way that is both clear and readable. (James Hatley did this for me in some of his articles, too. I’m grateful to both of them for that.) Now I’m very much looking forward to Mooney’s next book, Living Philosophy in Kierkegaard, Melville, and Others: Intersections of Literature, Philosophy, and Religion.

Patrick Hicks, Library of the Mind: New & Selected Poems. If you’re not reading poetry, what has gone wrong with your life? Never mind, don’t try to answer that. Instead, just read good poetry. Here’s an excellent place to start. Each page makes me slow down and collect myself again.

Malin Grahn-Wilder, Gender and Sexuality in Stoic Philosophy. I teach ancient and medieval philosophy, and I find books like this keep me sharp. The organization of the book is excellent, and so is the content. This is a nicely written history of ideas, and a useful resource for scholars.

Jacob Goodson, Strength of Mind: Courage, Hope, Freedom, Knowledge. I’ve known Jacob for a few years, and I like everything he writes. This is no exception. Jacob’s an excellent teacher with an encyclopedic mind. I have the good fortune of spending time with him in person each year, and those conversations become miniature seminars that leave me feeling refreshed and energized; he tills the soil of the mind. So you should buy this book and enjoy it. But I’m especially looking forward to his next collaboration with Brad Elliott Stone, Introducing Prophetic Pragmatism: A Dialogue on Hope, the Philosophy of Race, and the Spiritual Blues. That will be out later this year.

Evan Selinger and Brett Frischmann, Re-Engineering Humanity. This is one of a small number of books that I’ve gone back to multiple times. Selinger is worth following on Twitter for a daily dose of sharp observations on how we are letting technology race ahead of ethics. Once you’ve looked at what he posts there, you’ll find you’re either ready to check out of digital life altogether, or to go into the deep dive of this book so you can get a better handle on what to do next.

Yvon Chouinard, Craig Mathews, and Mauro Mazzo, Simple Fly Fishing: Techniques for Tenkara and Rod & Reel. Revised second edition, with paintings by James Prosek. Come for the zen-like techniques, stay for the beauty of each page, and take the time to read those small things like why Chouinard mapped several unmapped mountain routes, then burned the maps. “But standing around the campfire one day, we decided to burn our notes…There need to be a few places left on this crowded planet where ‘here be dragons’ still defines the unknown regions of maps. Then I went fishing.” If you follow me on social media, you know I write about trout and salmon. You might also know, if you pay close attention, that I love the places that the fish live, I love swimming with the fish, and I love the things and people they’re connected to. But the more I fish, the less I feel the need to fish, and the happier I am being near the fish. Tenkara rods are a very old way of being still with the fish.

David C. Krakauer, ed. Worlds Hidden In Plain Sight: The Evolving Idea of Complexity at the Santa Fe Institute 1984-2019. This is one I’m working through slowly, and I’m not reading it cover-to-cover. The organization of this book makes it one that invites a bit of flaneurism, reading deeply and thoughtfully, but in the manner of what Thoreau calls “sauntering”: not a linear, business-like drive to the finish line, but a walk without purpose other than to see what is there. This is one of the best kinds of learning. The book is, indirectly, about the importance of cross-disciplinary reading; the importance of philosophy of science for everything from understanding markets to climate change; and the helpful and constant reminder we don’t know enough about the things we quantify, even though we talk about the quantification with such authority. The book is priced at about ten bucks, but it's worth far more than that.

Is there something better than reading well-considered words? Perhaps, but all of these books have so far been well worth my while. I hope you have good books in your life as well.

*****

In the interest of full disclosure: I know a number of these authors, and I'm glad to know them, and I'm glad to tell you about their books. And I'm not paid a thing to tell you about their books; I just get the satisfaction of sharing good things with others.

∞

I'm preparing to teach a course on ecology and nature writing this summer in Alaska. One of the keys to becoming a good writer is to read good writing, so I've been asking for book recommendations that might help me prepare for my course.

The focus of the course will be the char species of Alaska. These species, all members of the genus salvelinus, are commonly thought of as trout. Brook trout and lake trout are both char, as are Dolly Vardens and arctic char.

These are beautiful fish. I think many anglers love them simply because they are so beautiful to look at. When I pull one from the water I am immediately torn between wanting to hold this precious thing closely and the urge to release it immediately, before my coarse hands pollute its loveliness. The name "char" might come from Celtic roots, like the Gaelic cear, meaning "blood." They are more multi-hued than rainbow trout. The red on their sides and fins catches the eye and holds the gaze.

Over the years I spent researching and writing my own book on brook trout, I did a lot of reading. Some books call me back again and again, like Henry Bugbee's The Inward Morning and Steinbeck's Log From The Sea of Cortez. Neither one is chiefly about fly-fishing or about trout, but they're both written in a way that makes me re-think how I view the world. And they do both talk a good deal about fish, and fishing.

Of course there are the classics of fly-fishing, too. Still, as I've asked for suggestions, I've been surprised by how many books there are that I haven't read or haven't even heard of. Just how many books about fish and fishing do we need? Are there really so many stories to tell?

If the point of writing books about fish is to give techniques, or data, then we don't need many at all. But stories about fish and fishing are rarely about the taking of fish. More often they are about the states of mind that open up as we prepare to enter the water, or as we stand there in the river. Fishing is to such states of consciousness what kneeling is to prayer; the posture is perhaps not essential, but it is a bodily gesture that does something to prepare us to be open to a certain kind of experience. I won't belabor this point. Read my book if you really want me to go on about fishing and philosophy. For now, let me present some of my recommendations, plus the recommendations I've received:

On Nature

I teach environmental philosophy and ecology, so I begin with some orienting books.

Some Favorites

Classics

These have been recommended time and again. I'm not sure many people ever actually read the first two, though they become prized volumes in the libraries of anglers around the world.

Most Recommended

Fly-Tying

Places

One reason why there is so much writing about fishing is that fishers tend to be students of particular places. Yes, some people fish by indiscriminately approaching water and drowning hooked worms therein, but experience tends to cure most young anglers of that method. Fishing puts us into contact with what we cannot see (or cannot see well) under the water; experienced anglers learn to read the signs above the water and the place itself. We return to the same place as we return to beloved passages in books or to favorite songs, to know them better through repetition.

Other Frequent Recommendations

If I talk to a group of anglers about books for long enough, one or more of these will eventually be mentioned. Stylistically and in terms of content, they're quite different, but they all seem to speak to important moods and thoughts of anglers.

Other Recommendations

Most of these I don't know at all, so I'm not recommending them, just mentioning them. Of course, if you have more recommendations (or corrections), please feel free to add them to the comments section, below.

I'll conclude with a few other recommendations. First, when I've asked for recommendations about texts, a handful of people tell me "Tenkara." This isn't a text, but a kind of rod, and a method of fly-fishing. And yet people continue to say that word to me when I ask for texts. Why is that? I have a few guesses: there isn't a lot written about tenkara, but people who practice it have come to love its simplicity and grace. I'm not a tenkara fisher (yet) but I'm eager to learn. I have a feeling that tenkara, like so many spiritual practices or like some martial arts, is something that makes people feel they way great writing makes us feel: in it we transcend the immediacy of our environment.

Along those lines, one commenter on Facebook said this to me about my students: "Give them [a] fly rod and a stream and let them write [their] own story." There is wisdom here. It is one thing to read about waters, and quite another to enter the waters on one's own feet. Even so, I think it's important and wise to learn from those who've gone before us, too.

If you're interested in seeing some of my other book recommendations, have a look at this, this, and this.

Recommended Reading: Fly-Fishing and Trout

|

The focus of the course will be the char species of Alaska. These species, all members of the genus salvelinus, are commonly thought of as trout. Brook trout and lake trout are both char, as are Dolly Vardens and arctic char.

These are beautiful fish. I think many anglers love them simply because they are so beautiful to look at. When I pull one from the water I am immediately torn between wanting to hold this precious thing closely and the urge to release it immediately, before my coarse hands pollute its loveliness. The name "char" might come from Celtic roots, like the Gaelic cear, meaning "blood." They are more multi-hued than rainbow trout. The red on their sides and fins catches the eye and holds the gaze.

Over the years I spent researching and writing my own book on brook trout, I did a lot of reading. Some books call me back again and again, like Henry Bugbee's The Inward Morning and Steinbeck's Log From The Sea of Cortez. Neither one is chiefly about fly-fishing or about trout, but they're both written in a way that makes me re-think how I view the world. And they do both talk a good deal about fish, and fishing.

|

| Mayfly on my reel. Summer 2014, Maine. |

If the point of writing books about fish is to give techniques, or data, then we don't need many at all. But stories about fish and fishing are rarely about the taking of fish. More often they are about the states of mind that open up as we prepare to enter the water, or as we stand there in the river. Fishing is to such states of consciousness what kneeling is to prayer; the posture is perhaps not essential, but it is a bodily gesture that does something to prepare us to be open to a certain kind of experience. I won't belabor this point. Read my book if you really want me to go on about fishing and philosophy. For now, let me present some of my recommendations, plus the recommendations I've received:

On Nature

I teach environmental philosophy and ecology, so I begin with some orienting books.

Some Favorites

Classics

These have been recommended time and again. I'm not sure many people ever actually read the first two, though they become prized volumes in the libraries of anglers around the world.

Most Recommended

Fly-Tying

Places

One reason why there is so much writing about fishing is that fishers tend to be students of particular places. Yes, some people fish by indiscriminately approaching water and drowning hooked worms therein, but experience tends to cure most young anglers of that method. Fishing puts us into contact with what we cannot see (or cannot see well) under the water; experienced anglers learn to read the signs above the water and the place itself. We return to the same place as we return to beloved passages in books or to favorite songs, to know them better through repetition.

Other Frequent Recommendations

If I talk to a group of anglers about books for long enough, one or more of these will eventually be mentioned. Stylistically and in terms of content, they're quite different, but they all seem to speak to important moods and thoughts of anglers.

Other Recommendations

Most of these I don't know at all, so I'm not recommending them, just mentioning them. Of course, if you have more recommendations (or corrections), please feel free to add them to the comments section, below.

I'll conclude with a few other recommendations. First, when I've asked for recommendations about texts, a handful of people tell me "Tenkara." This isn't a text, but a kind of rod, and a method of fly-fishing. And yet people continue to say that word to me when I ask for texts. Why is that? I have a few guesses: there isn't a lot written about tenkara, but people who practice it have come to love its simplicity and grace. I'm not a tenkara fisher (yet) but I'm eager to learn. I have a feeling that tenkara, like so many spiritual practices or like some martial arts, is something that makes people feel they way great writing makes us feel: in it we transcend the immediacy of our environment.

Along those lines, one commenter on Facebook said this to me about my students: "Give them [a] fly rod and a stream and let them write [their] own story." There is wisdom here. It is one thing to read about waters, and quite another to enter the waters on one's own feet. Even so, I think it's important and wise to learn from those who've gone before us, too.

*****

If you're interested in seeing some of my other book recommendations, have a look at this, this, and this.

∞

More Books Worth Reading

One of the great pleasures of being a teacher is reading. To do my job well, I have to read. If I don't read a lot, I won't keep up with my field and I'll be a poorer teacher. Fortunately, I like reading.

Even so, one of the great surprises of being a teacher is that, at the end of a long day of work reading, I like to unwind with a good book. Go figure.

The last few months have brought me a surfeit of good books to unwind with. Here are some of the recent books I've enjoyed:

Even so, one of the great surprises of being a teacher is that, at the end of a long day of work reading, I like to unwind with a good book. Go figure.

The last few months have brought me a surfeit of good books to unwind with. Here are some of the recent books I've enjoyed:

∞

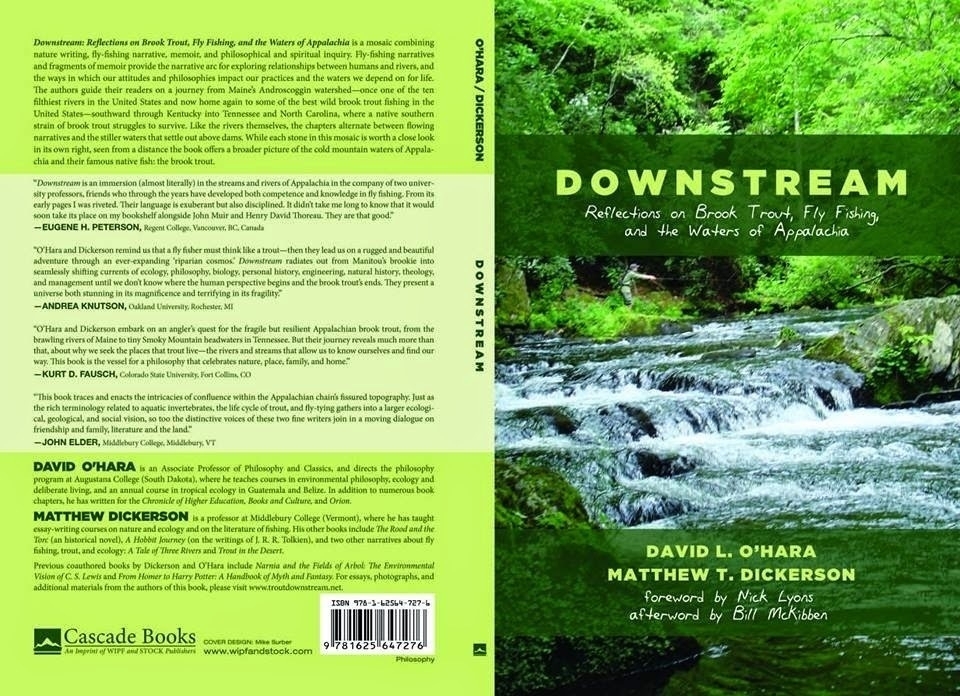

Downstream: My New Book On Brook Trout and Appalachian Ecology

You can find it here, on the publisher's website, for a very reasonable price.

It is now listed on Amazon as well, though not yet in stock there.

I'm very grateful for the foreword by Nick Lyons, the afterword by Bill McKibben, and the kind words offered by such a wide range of brilliant scholars of theology, literature, and science, like Eugene Peterson, Andrea Knutson, Kurt Fausch, and John Elder.

It is now listed on Amazon as well, though not yet in stock there.

I'm very grateful for the foreword by Nick Lyons, the afterword by Bill McKibben, and the kind words offered by such a wide range of brilliant scholars of theology, literature, and science, like Eugene Peterson, Andrea Knutson, Kurt Fausch, and John Elder.

∞

Librarians: Saving The Past, Saving The Future

This week in Timbuktu terrorists fleeing French forces torched an ancient library, destroying invaluable manuscripts. The good news is that some locals managed to save some of the manuscripts, and others have preserved them digitally. Not all is lost.

But sadly, much is lost. Some of my academic friends, upon hearing this news, denounced the terrorists as worse than murderers. I won’t go so far as to say that the destruction of these antiquities is the equivalent of murder, but it seems to arise from a similar intent: the desire to dominate others.

People who burn books are trying to limit the thoughts of those who are alive. Book-burning is an attempt to silence authors, to eliminate their voices. At its best it is insultingly paternalistic; at its worst it is bullying and even tyrannical.

Which suggests that the work of librarians, and of all who preserve books, is the opposite of tyranny. To save books, and to make them available to others, is to nourish democracy. It is to preserve the voices of the past, the Cadmean souls of long-lost authors, for the sake of what we may yet learn from them.

We sometimes depict librarians as pale denizens of musty stacks, lurking behind counters in drab frocks and silencing those who dare to speak too loudly in their bookish caverns. But the function of the librarian is quite the opposite of this; on the rare occasion that they ask us to be quiet it is only so that the voices of authors may speak loudly across space and time. It is not just uniformed warriors who defend liberty; the librarian is also an essential servant of freedom. We mustn’t forget that.

But sadly, much is lost. Some of my academic friends, upon hearing this news, denounced the terrorists as worse than murderers. I won’t go so far as to say that the destruction of these antiquities is the equivalent of murder, but it seems to arise from a similar intent: the desire to dominate others.

People who burn books are trying to limit the thoughts of those who are alive. Book-burning is an attempt to silence authors, to eliminate their voices. At its best it is insultingly paternalistic; at its worst it is bullying and even tyrannical.

Which suggests that the work of librarians, and of all who preserve books, is the opposite of tyranny. To save books, and to make them available to others, is to nourish democracy. It is to preserve the voices of the past, the Cadmean souls of long-lost authors, for the sake of what we may yet learn from them.

We sometimes depict librarians as pale denizens of musty stacks, lurking behind counters in drab frocks and silencing those who dare to speak too loudly in their bookish caverns. But the function of the librarian is quite the opposite of this; on the rare occasion that they ask us to be quiet it is only so that the voices of authors may speak loudly across space and time. It is not just uniformed warriors who defend liberty; the librarian is also an essential servant of freedom. We mustn’t forget that.

∞

Books Worth Reading

After my recent post about great books, pedagogy and hope I've had some queries about what I'm reading and what I recommend.

I'm reluctant to make book recommendations because I think what you read should have some connection to what you care about and what you've already read. In general, my recommendations are these:

First, I agree with what C.S. Lewis once said:* it's good to read old books. Old books and books written by people who are not like us have a remarkable power of helping us to see the world with fresh eyes.

Second, let your reading grow organically. If you liked a book you read, let it lead you to the next book you read. Often, books name their connections to other books. Or authors will name those connections, dependencies, and appreciations. The first time I read Lewis's Out of the Silent Planet, I missed the fact that the preface named H.G. Wells and that the afterword referred to Bernardus Silvestris. When I read it again as an adult, I caught those obvious references and let them lead me to other books.**

Third, I recommend learning the classics. That's an intentionally vague term, and I use it to mean that it's good to know those books that have given your culture its vocabulary. People who have stories in common have enriched possibilities for conversation. One of my favorite Star Trek episodes explored this idea, and it appealed to me because I believe that it's not far from how language really grows. If you need a place to start, check out one of the various lists of "great books" floating around out there. For instance this one, or this one.

With all that being said, if you're still interested in what I'm reading, here are some older titles I've enjoyed in the last year or so:

* Lewis said this in his introduction to Athanasius' On The Incarnation (which, by the way, is now available from SVS Press in a dual-language edition, Greek on one page, English on the facing page.)

** There are two excellent books on Lewis' "Space Trilogy" or (as I think it should be called) "Ransom Trilogy": This one by Sanford Schwartz, and this one by David Downing.

I'm reluctant to make book recommendations because I think what you read should have some connection to what you care about and what you've already read. In general, my recommendations are these:

First, I agree with what C.S. Lewis once said:* it's good to read old books. Old books and books written by people who are not like us have a remarkable power of helping us to see the world with fresh eyes.

Second, let your reading grow organically. If you liked a book you read, let it lead you to the next book you read. Often, books name their connections to other books. Or authors will name those connections, dependencies, and appreciations. The first time I read Lewis's Out of the Silent Planet, I missed the fact that the preface named H.G. Wells and that the afterword referred to Bernardus Silvestris. When I read it again as an adult, I caught those obvious references and let them lead me to other books.**

Third, I recommend learning the classics. That's an intentionally vague term, and I use it to mean that it's good to know those books that have given your culture its vocabulary. People who have stories in common have enriched possibilities for conversation. One of my favorite Star Trek episodes explored this idea, and it appealed to me because I believe that it's not far from how language really grows. If you need a place to start, check out one of the various lists of "great books" floating around out there. For instance this one, or this one.

With all that being said, if you're still interested in what I'm reading, here are some older titles I've enjoyed in the last year or so:

*****

* Lewis said this in his introduction to Athanasius' On The Incarnation (which, by the way, is now available from SVS Press in a dual-language edition, Greek on one page, English on the facing page.)

** There are two excellent books on Lewis' "Space Trilogy" or (as I think it should be called) "Ransom Trilogy": This one by Sanford Schwartz, and this one by David Downing.

*****

I realize I'm posting a lot about Great Books and St John's College lately. I'll stop soon. They don't pay me for this; I'm just a grateful alumnus.

*****

Update, 8/11/14: I've posted another list like this one on my blog, with new recommendations. You can find it here.

∞

Great Books, Pedagogy, and Hope

Great Books and the Great Conversation

About fifteen years ago I enrolled in the "Great Books" M.A. program at St John's College in Santa Fe, New Mexico. It was one of the best decisions I've ever made.

Much as I appreciate my undergraduate education, too often it rewarded me for concealing my ignorance and emphasizing what I already knew. The problem, of course, is that my ignorance was thus shielded from the sterilizing sunlight of others' scrutiny and instruction.

Confessing Our Ignorance

Matthew Davis, my tutor and advisor at St John's, won me over to another way of viewing literature when, on one of the first days we met, he pointed to a passage in Plato's Republic and said "I have always wondered what Plato means by that." Looking up at the class, he asked, "Do any of you have any ideas about what he might be trying to say?"

Mr. Davis is the first professor I recall who openly confessed his ignorance, and who thereby modeled what it means to open oneself to the instruction of a great text. Not much has shaped my academic life as much as that.

Grappling With Classic Texts

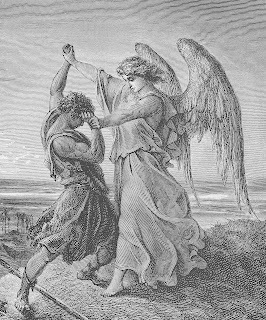

As I have begun to mature into my own place as a teacher, I often think that this is the best thing I can give my students: not professorial and authoritative descriptions of texts, but an example of what it means to be a student. I can try to be an example of someone who sits with texts and listens to them, grappling with them, like Jacob with the angel or like Menelaus with Proteus: persistently grappling with my superior and refusing to let go until I receive a blessing. (Selah.)

For the last few years I have been seeking out and reading classic novels. As I read them I feel like an apprentice architect touring buildings, looking not just at the outward form and function but looking for the supporting structure, trying to notice the decisions the artist made about what to include and what to omit.

Along the way, I have begun trying to write bits of dialogue, scenes, characters, and other elements of fiction. I'm not trying to write a novel so much as trying to perform experiments the way high school science students do in labs: not to discover something new but to learn haptically, kinesthetically, experientially what the masters already know. I can't say that I've learned to write novels, so don't expect anything from me there. But as I've paid attention, I feel I've begun to squeeze some blessings out of the books, including some unexpected ones.

I've noticed, for instance, that Craig Nova writes about the olfactory sense in a way that makes me notice aromas I never noticed before. John Steinbeck has begun to make me care more about friendship, and about the people in front of me. Harold Frederic has me rethinking my early faith, and this is helping me look ahead as I try to nurture it into a faith worth having. Novels are helping me see the world differently.

So What Does This Have To Do With Hope?

I just finished Graham Greene's The Honorary Consul. Apparently this was Greene's favorite of his own works, and I can see why. Like many of the really good novels I've read, it has left me thinking about a range of topics, and longing for someone to talk about it with.

Which brings me to hope. I started reading Greene because Bill Swart, my friend and colleague, told me about how good Greene's novels are. Bill was right about this, so I sought him out the other day to talk more about Greene. We said too much to cover it all here, but Bill said something I can't bear not to repeat. When we began discussing Greene's The Power and the Glory, Bill said "That book gave me hope that my own self-perception might be wrong."

If you know the novel, you know why, because you know how Greene's characters wrestle with being both sinners and saints. If you don't know the novel, let me recommend it to you.

We Should Keep Teaching And Reading Fiction

I still have a lot to learn about novels. I doubt I'll ever write one - or a good one, anyway. But I'm delighting in reading them. Perhaps that's why they matter so much: they delight us, and capture us. When I'm in a good book I feel like I'm really in it. I stop seeing words on a page and start seeing, with some inner eye, the world the novelist sees.

And like all my other travels, journeys into fiction leave me a different person. I see different possibilities, I see -- and smell -- my world differently. I know it's important to teach young people to read non-fiction, but teaching fiction might be for them what The Power and the Glory was for Bill: a tonic for his soul, a sweet drink of hope that didn't just entertain, but that allowed him to envision his life, his work, and his purpose in an entirely new way.

About fifteen years ago I enrolled in the "Great Books" M.A. program at St John's College in Santa Fe, New Mexico. It was one of the best decisions I've ever made.

Much as I appreciate my undergraduate education, too often it rewarded me for concealing my ignorance and emphasizing what I already knew. The problem, of course, is that my ignorance was thus shielded from the sterilizing sunlight of others' scrutiny and instruction.

Confessing Our Ignorance

Matthew Davis, my tutor and advisor at St John's, won me over to another way of viewing literature when, on one of the first days we met, he pointed to a passage in Plato's Republic and said "I have always wondered what Plato means by that." Looking up at the class, he asked, "Do any of you have any ideas about what he might be trying to say?"

Mr. Davis is the first professor I recall who openly confessed his ignorance, and who thereby modeled what it means to open oneself to the instruction of a great text. Not much has shaped my academic life as much as that.

Grappling With Classic Texts

As I have begun to mature into my own place as a teacher, I often think that this is the best thing I can give my students: not professorial and authoritative descriptions of texts, but an example of what it means to be a student. I can try to be an example of someone who sits with texts and listens to them, grappling with them, like Jacob with the angel or like Menelaus with Proteus: persistently grappling with my superior and refusing to let go until I receive a blessing. (Selah.)

For the last few years I have been seeking out and reading classic novels. As I read them I feel like an apprentice architect touring buildings, looking not just at the outward form and function but looking for the supporting structure, trying to notice the decisions the artist made about what to include and what to omit.

Along the way, I have begun trying to write bits of dialogue, scenes, characters, and other elements of fiction. I'm not trying to write a novel so much as trying to perform experiments the way high school science students do in labs: not to discover something new but to learn haptically, kinesthetically, experientially what the masters already know. I can't say that I've learned to write novels, so don't expect anything from me there. But as I've paid attention, I feel I've begun to squeeze some blessings out of the books, including some unexpected ones.

I've noticed, for instance, that Craig Nova writes about the olfactory sense in a way that makes me notice aromas I never noticed before. John Steinbeck has begun to make me care more about friendship, and about the people in front of me. Harold Frederic has me rethinking my early faith, and this is helping me look ahead as I try to nurture it into a faith worth having. Novels are helping me see the world differently.

So What Does This Have To Do With Hope?

I just finished Graham Greene's The Honorary Consul. Apparently this was Greene's favorite of his own works, and I can see why. Like many of the really good novels I've read, it has left me thinking about a range of topics, and longing for someone to talk about it with.

Which brings me to hope. I started reading Greene because Bill Swart, my friend and colleague, told me about how good Greene's novels are. Bill was right about this, so I sought him out the other day to talk more about Greene. We said too much to cover it all here, but Bill said something I can't bear not to repeat. When we began discussing Greene's The Power and the Glory, Bill said "That book gave me hope that my own self-perception might be wrong."

If you know the novel, you know why, because you know how Greene's characters wrestle with being both sinners and saints. If you don't know the novel, let me recommend it to you.

We Should Keep Teaching And Reading Fiction

I still have a lot to learn about novels. I doubt I'll ever write one - or a good one, anyway. But I'm delighting in reading them. Perhaps that's why they matter so much: they delight us, and capture us. When I'm in a good book I feel like I'm really in it. I stop seeing words on a page and start seeing, with some inner eye, the world the novelist sees.

And like all my other travels, journeys into fiction leave me a different person. I see different possibilities, I see -- and smell -- my world differently. I know it's important to teach young people to read non-fiction, but teaching fiction might be for them what The Power and the Glory was for Bill: a tonic for his soul, a sweet drink of hope that didn't just entertain, but that allowed him to envision his life, his work, and his purpose in an entirely new way.

∞

Reading the Holidays

This Thanksgiving holiday I've just re-read Abraham Lincoln's Proclamation of Thanksgiving and I might read some of the Puritans this weekend as well*, or perhaps Washington.

This practice of reading the holidays began for me about ten years ago on July 4th. I decided then that I'd re-read the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution. I was guessing that it had been so long since I'd read them, I'd probably forgotten much of what they say. My experiment proved my guess to be right.

I was struck, as I read them, just how remarkable these documents are. Since then, I've repeated this almost every year. Each time I re-read these documents, I find them moving. They're beautifully written, and they strive for things that are, in my estimation, praiseworthy.

I've begun to add other readings for other holidays as well. On MLK, Jr. Day, (and sometimes on April 4, the anniversary of his death) I listen to his "I Have A Dream" speech or read his "Letter from a Birmingham Jail." I admit it: both of these regularly make me cry.

Of course, I also read the appointed Scriptures for Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost, and for some other feast days as well. But here I'm interested in those holidays that are not holy-days but secular feasts. How about you? Do you have readings you associate with such holidays? What do you recommend?

--------

* (If you're interested, you can see my article on Puritanism by clicking here and searching for pp 631-632)

This practice of reading the holidays began for me about ten years ago on July 4th. I decided then that I'd re-read the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution. I was guessing that it had been so long since I'd read them, I'd probably forgotten much of what they say. My experiment proved my guess to be right.

I was struck, as I read them, just how remarkable these documents are. Since then, I've repeated this almost every year. Each time I re-read these documents, I find them moving. They're beautifully written, and they strive for things that are, in my estimation, praiseworthy.

I've begun to add other readings for other holidays as well. On MLK, Jr. Day, (and sometimes on April 4, the anniversary of his death) I listen to his "I Have A Dream" speech or read his "Letter from a Birmingham Jail." I admit it: both of these regularly make me cry.

Of course, I also read the appointed Scriptures for Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost, and for some other feast days as well. But here I'm interested in those holidays that are not holy-days but secular feasts. How about you? Do you have readings you associate with such holidays? What do you recommend?

--------

* (If you're interested, you can see my article on Puritanism by clicking here and searching for pp 631-632)