British Museum

∞

No Flash!

My job as a college professor brings me to a lot of museums and archives, and this summer has been especially full of visits to museums, historical sites, and archives in Greece, Norway, the U.K., and the U.S.

As a kid I found most museums boring, but now I really appreciate and enjoy them. I've spent many days of my life in the British Museum and in several museums in Athens, and each time I'm there I feel that time is rewarded with fresh discoveries and with reacquaintance with familiar objects.

Some museums have a reasonable policy of not permitting flash photography, since the bright light of camera flashes can degrade the colors of paint and dyes. Others must insist on no photography when the objects on display are on loan from owners who will not permit reproductions of their images.

But in general, I object when museums and archives prohibit photography, especially when the aim is to force more visitors to come to the physical site. Most people the world over will never be able to visit the world's great museums. And many scholars could benefit from digital images of archival materials. During a recent visit to an archive that hosts many of Henry David Thoreau's papers, I was disappointed to learn that I would not be permitted to take photos of some of the papers I wanted to read later. This forces scholars to spend more time in the archive, which means spending more money - simply prohibitive for many of us. So I type, or scribble, as quickly as I can to transcribe texts in some archives, and hope that I can somehow find what I need in the time I have.

The Ballpoint As A Tool For Seeing

But what if what you want to remember is not a text but an image? Scott Parsons, a gifted artist and a friend of mine, has taught me that one need not be very talented with a pen to begin to capture images. As Dr. Cornelius said in one of Lewis's stories, "A scholar is never without [pen and paper]," and I've tried to make that my rule, too, carrying pen and paper with me everywhere. Scott tells me that a cheap ballpoint pen is, after all, one of the best tools for seeing.

It turns out, he's right: the pen is often mightier than the camera. I think this is because the camera captures all available light, while the pen only captures what my eye and hand tell it to. The chief obstacle to overcome is the disconnect between what my eye sees and what my hand draws. Scott has pointed out to me that this is not the fault of my hand so much as a problem of mistaking what I think I see for what I actually see. In other words, it is a problem of misdirected attention, when I pay attention to what I think is there rather than to what the light is actually doing.

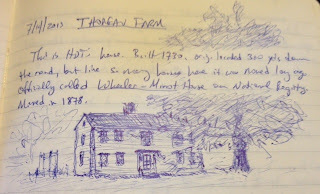

So far, no one in any museum has objected to my drawing what I see. In most cases, when I draw pictures, people seem honored that I should take the time. I drew this picture of the Thoreau homestead in Concord this summer, and a curator there happened to see it as I journaled. She seemed pleased that I took the time to try to draw it. I find that taking the time to draw helps me to notice details I'd have otherwise missed. You can see I'm not a great artist, little improved from my youth. But I'm not ashamed, because even if it's not a brilliant representation, it doesn't need to be; it is a record, in blue lines, of ten minutes of attention. The image is not a photograph; it is a symbol of memory, like a call number for a book in a library that helps me to recall quickly the time I spent sitting on the grass in Concord considering the place where Henry David grew up.

Memories Of Delight

I've also begun drawing inside people's homes when I'm a guest there - always with permission, of course. This summer several kind Norwegian friends took me in for a week, giving me space to write while overlooking a fjord, and cooking me delicious Norwegian food. In the evening we built fires in the hearth and talked quietly or played cards. These are fond memories with friends, but they're also memories of delight in seeing new shapes of things. Norwegians build fires and eat waffles as we Americans do, but the fireplaces and the waffle irons are different from the ones I know from my home. The waffles I saw were all shaped like heart-flowers, giving visual delight in addition to the delightful taste (though I'm not yet sold on brown cheese as a topping.) The fireplaces I saw were all open on not just one side, but two. They looked different, but it was only when I began to draw them that I noticed what I was seeing. This is a small thing, perhaps, but it is a reminder that what I take to be the natural shape of things often has as much to do with the traditions I grew up with as with nature. As an aside, when I take the time to draw pictures, it often seems to be taken as a sign of respect, which is just how I intend it: this place you live in, this object in your home, is so wonderful to me that I wish to give it my attention and make it a permanent resident in my journal, the log-book of my heart. May I? Thank you, and thank you for the hospitality that allowed me to witness this.

Pics Or It Didn't Happen

Sometimes I choose not to take photos simply because the camera is itself a sign. When we hold it in front of our face, it becomes not just a lens through which we see, but a symbol of distance: this moment, this image, matters because it will matter somewhere else, somewhen else. There's nothing wrong with wanting to preserve the moment, but when the apparatus becomes the medium through which we perceive everything - when we feel we must record a photonic image of everything to make the moment real, reality itself somehow becomes less to us.

Icons As Luminous Doorways

This summer I had the privilege of visiting the Monastery of Hosios (Saint) Loukas near Delphi in Greece. I'm not Orthodox, but I have real appreciation for what I learn from the Orthodox traditions. An Orthodox priest in my town has told me that icons are not objects of worship, but means of worship, images that help us to pray, just as windows help us to see. The pray-er who regards the icon isn't supposed to see the icon, but, as with windows, to see through the icon. In some sense the artistic image is intended to vanish when it is doing what it was intended to do. This language has been a little bit mysterious to me at times, but at the monastery this summer I had an illustrative experience: I stood in a doorway with bright sunlight shining behind me. Ahead, I could see through another doorway into the narthex of a chapel, and then through another doorway, to the altar at the far end. Beside every Orthodox altar there is an icon of Christ. This one was covered with glass, as icons often are. The glass reflected back to me the image of the doorway behind me, as though in the center of the image of Christ there were a luminous doorway. I tried to take a photo of this, but the contrasts were too great. So I took out my paper and pen and sketched what I saw. It's not a superb image, but it turned out far better than my photographic attempts did. And, as in other cases, I found myself feeling considerably more present and more respectful of the place.

The View From The Pew

This was the case with several other holy sites I visited this summer as well. I had the privilege of hearing Robert Richardson lecture on Emerson in the Unitarian church in Concord, MA this summer, and then to visit the "African Meeting House" in Boston, a site of worship and of community activism for African Americans in the 19th century. It somehow didn't feel right to let the camera intrude into these places. The pen, by contrast, felt like an instrument properly reverent. Each stroke of the pen strengthening lines became like a prayer or an act of gratitude and reverence for the places I was in. In each case I sketched a "view from my pew," the view I had while sitting as worshipers have sat there in times past - and present.

No Photos!

But to return to the complaint with which I began this piece, too many places insist that no photography be allowed inside. While participating in a Summer Institute on Transcendentalism sponsored by the National Endowment for the Humanities this summer, I was able to visit some wonderful places, like the Thoreau Homestead, several of the homes of Louisa May Alcott, and Emerson's home. Visiting these places makes me a better teacher: they help me to tell a better story about the texts and ideas that emerged from them. Bronson Alcott, Louisa May's father, may have been odd, but his oddity is fascinating and delightful. He built this outbuilding to house his Concord School of Philosophy, for instance:

Architecture As The Embodiment Of Ideas

And he had some beautiful ideas about education: like the belief that children should be allowed to learn what they love to learn, that they should become bodily and sensorily engaged in their learning, that they should run and play and have recess, that art and literature should be significant in their learning, and so on. I knew these ideas before visiting his Concord home and Fruitlands, but seeing the buildings he built to house his ideas helps me to see how he envisioned those ideas at work.

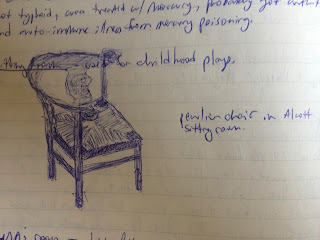

Unfortunately, I can only show you the outside of the buildings at the Alcott house, because there's no photography allowed inside, nor at the Emerson home either. So if you live far away, tant pis. I guess you'll have to just travel and visit it. Or, if you like, I can share the sketches I was able to make in our hurried tour. Yes, let's do that. I loved this chair, which is so oddly shaped. In a time when so many chairs seemed intended to make you sit ramrod straight, this one seems to invite you to slouch in different directions, to be at ease in your own body, to delight in sitting in the company of others:

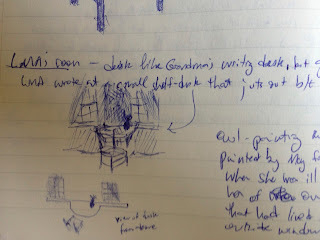

The Alcotts weren't wealthy, but Bronson and his wife managed to provide each of their children with a room of their own, and each of those rooms is suited to the disposition and arts of the child. Louisa May's room has a beautiful little half-moon shelf-desk jutting out between two large windows, perfect for writing stories and books, with excellent light. When I visited, the room was full of tourists, so a photo wouldn't have captured it anyway, and my drawing is very hasty and a little cramped itself, but here's a rough idea of what it looks like while standing beside her bed, plus an attempt to give the bird's-eye view:

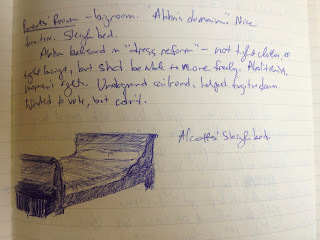

Bronson and his wife Abby had some lovely furniture, and I was especially captivated by their sleigh-bed. Its curved ends and gentle woodwork make the bed seem a place worth being, a place of rest and delight:

What I wish is that the owners and curators of these places would recognize that allowing visitors to take photos can help us to preserve the very places we are visiting, and to teach others about them. I understand the desire to make those places special, just as I understand the fear that if you allow images to be taken maybe fewer visitors will come. But for us teachers, taking pictures can be a way to allow our students to visit a place they might otherwise never go.

Thankfully, no one has yet prohibited my pen and paper. Or yours. I'm not up to Urban Sketchers quality, and may never be, but I'm not ashamed to use my pen as a visual instrument, nor to share with you what I've seen through it. And I hope you'll do the same.

Rebel Without A Camera: Museums, Images, and Memory

|

| My old Brownie. No flash! |

As a kid I found most museums boring, but now I really appreciate and enjoy them. I've spent many days of my life in the British Museum and in several museums in Athens, and each time I'm there I feel that time is rewarded with fresh discoveries and with reacquaintance with familiar objects.

Some museums have a reasonable policy of not permitting flash photography, since the bright light of camera flashes can degrade the colors of paint and dyes. Others must insist on no photography when the objects on display are on loan from owners who will not permit reproductions of their images.

But in general, I object when museums and archives prohibit photography, especially when the aim is to force more visitors to come to the physical site. Most people the world over will never be able to visit the world's great museums. And many scholars could benefit from digital images of archival materials. During a recent visit to an archive that hosts many of Henry David Thoreau's papers, I was disappointed to learn that I would not be permitted to take photos of some of the papers I wanted to read later. This forces scholars to spend more time in the archive, which means spending more money - simply prohibitive for many of us. So I type, or scribble, as quickly as I can to transcribe texts in some archives, and hope that I can somehow find what I need in the time I have.

The Ballpoint As A Tool For Seeing

But what if what you want to remember is not a text but an image? Scott Parsons, a gifted artist and a friend of mine, has taught me that one need not be very talented with a pen to begin to capture images. As Dr. Cornelius said in one of Lewis's stories, "A scholar is never without [pen and paper]," and I've tried to make that my rule, too, carrying pen and paper with me everywhere. Scott tells me that a cheap ballpoint pen is, after all, one of the best tools for seeing.

It turns out, he's right: the pen is often mightier than the camera. I think this is because the camera captures all available light, while the pen only captures what my eye and hand tell it to. The chief obstacle to overcome is the disconnect between what my eye sees and what my hand draws. Scott has pointed out to me that this is not the fault of my hand so much as a problem of mistaking what I think I see for what I actually see. In other words, it is a problem of misdirected attention, when I pay attention to what I think is there rather than to what the light is actually doing.

|

| Thoreau Farm |

|

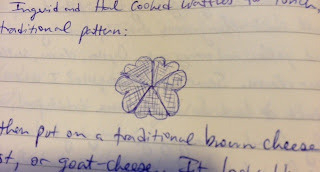

| Norwegian waffle: a bouquet of hearts |

|

| Norwegian fireplace |

I've also begun drawing inside people's homes when I'm a guest there - always with permission, of course. This summer several kind Norwegian friends took me in for a week, giving me space to write while overlooking a fjord, and cooking me delicious Norwegian food. In the evening we built fires in the hearth and talked quietly or played cards. These are fond memories with friends, but they're also memories of delight in seeing new shapes of things. Norwegians build fires and eat waffles as we Americans do, but the fireplaces and the waffle irons are different from the ones I know from my home. The waffles I saw were all shaped like heart-flowers, giving visual delight in addition to the delightful taste (though I'm not yet sold on brown cheese as a topping.) The fireplaces I saw were all open on not just one side, but two. They looked different, but it was only when I began to draw them that I noticed what I was seeing. This is a small thing, perhaps, but it is a reminder that what I take to be the natural shape of things often has as much to do with the traditions I grew up with as with nature. As an aside, when I take the time to draw pictures, it often seems to be taken as a sign of respect, which is just how I intend it: this place you live in, this object in your home, is so wonderful to me that I wish to give it my attention and make it a permanent resident in my journal, the log-book of my heart. May I? Thank you, and thank you for the hospitality that allowed me to witness this.

Pics Or It Didn't Happen

Sometimes I choose not to take photos simply because the camera is itself a sign. When we hold it in front of our face, it becomes not just a lens through which we see, but a symbol of distance: this moment, this image, matters because it will matter somewhere else, somewhen else. There's nothing wrong with wanting to preserve the moment, but when the apparatus becomes the medium through which we perceive everything - when we feel we must record a photonic image of everything to make the moment real, reality itself somehow becomes less to us.

|

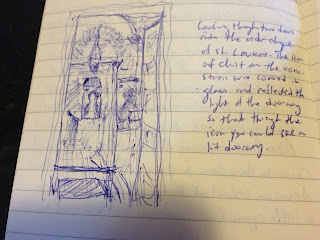

| Ecce: the heart of Christ, a luminous doorway |

This summer I had the privilege of visiting the Monastery of Hosios (Saint) Loukas near Delphi in Greece. I'm not Orthodox, but I have real appreciation for what I learn from the Orthodox traditions. An Orthodox priest in my town has told me that icons are not objects of worship, but means of worship, images that help us to pray, just as windows help us to see. The pray-er who regards the icon isn't supposed to see the icon, but, as with windows, to see through the icon. In some sense the artistic image is intended to vanish when it is doing what it was intended to do. This language has been a little bit mysterious to me at times, but at the monastery this summer I had an illustrative experience: I stood in a doorway with bright sunlight shining behind me. Ahead, I could see through another doorway into the narthex of a chapel, and then through another doorway, to the altar at the far end. Beside every Orthodox altar there is an icon of Christ. This one was covered with glass, as icons often are. The glass reflected back to me the image of the doorway behind me, as though in the center of the image of Christ there were a luminous doorway. I tried to take a photo of this, but the contrasts were too great. So I took out my paper and pen and sketched what I saw. It's not a superb image, but it turned out far better than my photographic attempts did. And, as in other cases, I found myself feeling considerably more present and more respectful of the place.

|

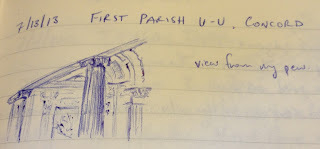

| First Parish, Concord, Mass. |

|

| African Meeting House, Boston, Mass. |

This was the case with several other holy sites I visited this summer as well. I had the privilege of hearing Robert Richardson lecture on Emerson in the Unitarian church in Concord, MA this summer, and then to visit the "African Meeting House" in Boston, a site of worship and of community activism for African Americans in the 19th century. It somehow didn't feel right to let the camera intrude into these places. The pen, by contrast, felt like an instrument properly reverent. Each stroke of the pen strengthening lines became like a prayer or an act of gratitude and reverence for the places I was in. In each case I sketched a "view from my pew," the view I had while sitting as worshipers have sat there in times past - and present.

No Photos!

But to return to the complaint with which I began this piece, too many places insist that no photography be allowed inside. While participating in a Summer Institute on Transcendentalism sponsored by the National Endowment for the Humanities this summer, I was able to visit some wonderful places, like the Thoreau Homestead, several of the homes of Louisa May Alcott, and Emerson's home. Visiting these places makes me a better teacher: they help me to tell a better story about the texts and ideas that emerged from them. Bronson Alcott, Louisa May's father, may have been odd, but his oddity is fascinating and delightful. He built this outbuilding to house his Concord School of Philosophy, for instance:

|

| Alcott's Concord School of Philosophy, Orchard House |

And he had some beautiful ideas about education: like the belief that children should be allowed to learn what they love to learn, that they should become bodily and sensorily engaged in their learning, that they should run and play and have recess, that art and literature should be significant in their learning, and so on. I knew these ideas before visiting his Concord home and Fruitlands, but seeing the buildings he built to house his ideas helps me to see how he envisioned those ideas at work.

|

| Chair in the Orchard House |

|

| Louisa May Alcott's writing desk |

|

| The Alcotts' sleigh-bed |

What I wish is that the owners and curators of these places would recognize that allowing visitors to take photos can help us to preserve the very places we are visiting, and to teach others about them. I understand the desire to make those places special, just as I understand the fear that if you allow images to be taken maybe fewer visitors will come. But for us teachers, taking pictures can be a way to allow our students to visit a place they might otherwise never go.

Thankfully, no one has yet prohibited my pen and paper. Or yours. I'm not up to Urban Sketchers quality, and may never be, but I'm not ashamed to use my pen as a visual instrument, nor to share with you what I've seen through it. And I hope you'll do the same.

∞

Visual Art and the Sacred: On The Importance Of Museums

I just finished writing an essay about the day Picasso made me fall down. I'm sending it off to my favorite editor, and if it's accepted, I'll post a link here.

The event I wrote about took place over two decades ago, when Picasso's Guernica was still housed in the Casón del Buen Retiro at the Prado Museum in Madrid. (It is now in the Reina Sofia, in a larger but - in my opinion - far inferior room. You can learn a bit about that here.)

Meanwhile, here's the upshot of my essay: education that's prepackaged and canned is not enough. Education is not the same as transferring information.

It involves informing students, to be sure, but what we tell students

should not satisfy them; it should provoke them to want more. Professors are not conduits of data; at our best we are like guides and gardeners.

As guides we point students in new directions and help them to see what

we see. Just as gardeners cannot make seeds grow but can prepare the

soil, so our teaching should be about increasing the fertility of minds

and then stepping back to watch what grows. Also, there is occasional

weeding involved.

As an undergraduate I knew very little about art. Part of this was my disposition: I liked representational art that was easy to look at quickly. Part of it was a matter of my worldview, and the suspicion that some modern artists who eschewed representational art were trying to undermine something good, obscurantists clouding clear vision.

Time spent in museums has changed me a good deal, as has making the acquaintance of Scott Parsons and Daniel Siedell, who have helped me quite a lot through their patient conversation and what they have written. (Scott and I wrote a chapter on teaching students about visual culture and the sacred in Ronald Bernier's short but illuminating book Beyond Belief, in which Dan also has a chapter.) Some of Makoto Fujimura's short writings, James Elkins's book On the Strange Place of Religion in Modern Art, and Gregory Wolfe's work at Image have also provided me with clear and helpful education about art that I resisted when I was younger.

Museums are certainly controversial. Curators make decisions that both expand and limit what we see, and this can be exploited to achieve sordid political ends. Some ideas and cultures are given preferential treatment while others are made less known by their omission. They tend to be located in large, wealthy cities, which means that poor people, rural people, and foreigners have limited or no access to them. But if the alternative is no museums, or all of the world's artifacts in private collections, I will take the museums we have, coupled with ever striving to make them better.

Because museums are a tangible way we can commit to remembering our history together. Museums are not safe deposit boxes where we lock away our treasures; they are Wunderkammers and classrooms where we may think and learn together.

I have come to love museums, especially the British Museum and the beautiful New Acropolis Museum in Athens (and I'm aware of the irony of that pairing) but I also love the little museums I find in small towns the world over.

The event I wrote about took place over two decades ago, when Picasso's Guernica was still housed in the Casón del Buen Retiro at the Prado Museum in Madrid. (It is now in the Reina Sofia, in a larger but - in my opinion - far inferior room. You can learn a bit about that here.)

|

| New Acropolis Museum, Athens |

As an undergraduate I knew very little about art. Part of this was my disposition: I liked representational art that was easy to look at quickly. Part of it was a matter of my worldview, and the suspicion that some modern artists who eschewed representational art were trying to undermine something good, obscurantists clouding clear vision.

Time spent in museums has changed me a good deal, as has making the acquaintance of Scott Parsons and Daniel Siedell, who have helped me quite a lot through their patient conversation and what they have written. (Scott and I wrote a chapter on teaching students about visual culture and the sacred in Ronald Bernier's short but illuminating book Beyond Belief, in which Dan also has a chapter.) Some of Makoto Fujimura's short writings, James Elkins's book On the Strange Place of Religion in Modern Art, and Gregory Wolfe's work at Image have also provided me with clear and helpful education about art that I resisted when I was younger.

Museums are certainly controversial. Curators make decisions that both expand and limit what we see, and this can be exploited to achieve sordid political ends. Some ideas and cultures are given preferential treatment while others are made less known by their omission. They tend to be located in large, wealthy cities, which means that poor people, rural people, and foreigners have limited or no access to them. But if the alternative is no museums, or all of the world's artifacts in private collections, I will take the museums we have, coupled with ever striving to make them better.

Because museums are a tangible way we can commit to remembering our history together. Museums are not safe deposit boxes where we lock away our treasures; they are Wunderkammers and classrooms where we may think and learn together.

I have come to love museums, especially the British Museum and the beautiful New Acropolis Museum in Athens (and I'm aware of the irony of that pairing) but I also love the little museums I find in small towns the world over.

∞

People Of The Waters That Are Never Still

Generations ago, one of my European grandfathers and one of my Native American grandmothers married, fusing in their offspring two peoples who had parted ways ages before, one heading west to the British Isles, the other to the Bering Strait and across to North America. I grew up in New York, near where they met and married, and my childhood is marked by memories of that land: tall oaks and white pines, deep forests, rocky crags over which the water pours, never still, always the same, always changing. The waterfalls of the Catskill Mountains are a constant presence in those mountains and in my memories. They are the waters of my mothers and fathers, and of my youth.

My family has since lost the languages those ancestors spoke, and this fusion of tribes has adopted the linguistic fusion of English. I have no intention of claiming a legal place among either of the nations from which I am descended, nor even to name them here. But I find that the memory of both, and of the lands they lived on, is rooted deeply in my consciousness of who I am. Last year, while visiting the British Museum, I saw a display of various Native American peoples, including my own. It was the only time a museum has moved me to tears. The words and ways of my forebears may be mostly gone, but they are not forgotten. My father taught me to remember them and what they knew of the land we lived on, and often, while teaching me to know the woods, he would remind me that those woods were old family acquaintances.

Jacob Wawatie and Stephanie Pyne, in their article "Tracking in Pursuit of Knowledge," cite Russell Barsh as saying that "what is 'traditional' about traditional knowledge is not its antiquity but the way in which it is acquired and used." Our word "tradition" comes from Latin roots that mean something like "giving over" or "handing down." Traditional knowledge is knowledge that is a gift from one generation to the next, a gift we give because we ourselves were given it. I am grateful to my father, in ways that I may never have told him - in ways that perhaps words cannot begin to tell - for the traditions he learned and loved and passed on to me. I'm grateful that he has not let me forget.

There is, of course danger in emphasizing one's heritage and one's roots, especially if we make that the source of a distinction between ourselves and others, or a way of diminishing the lives and traditions of others. Just as much as it matters to me that I am from the people of the waters of the Catskills, it matters to me that my ancestors shared those waters with one another, people from two continents recognizing, each in the other, the waters from which both arose.

For all that I have received, for the traditions like waters pouring over the cliffs, gifts like the Kaaterskill Creek, let me give thanks. Let me give thanks with my life, offering to those who come after me, a taste of the sweetness of those same waters.

(Photo: Kaaterskill Creek in New York State)

My family has since lost the languages those ancestors spoke, and this fusion of tribes has adopted the linguistic fusion of English. I have no intention of claiming a legal place among either of the nations from which I am descended, nor even to name them here. But I find that the memory of both, and of the lands they lived on, is rooted deeply in my consciousness of who I am. Last year, while visiting the British Museum, I saw a display of various Native American peoples, including my own. It was the only time a museum has moved me to tears. The words and ways of my forebears may be mostly gone, but they are not forgotten. My father taught me to remember them and what they knew of the land we lived on, and often, while teaching me to know the woods, he would remind me that those woods were old family acquaintances.

Jacob Wawatie and Stephanie Pyne, in their article "Tracking in Pursuit of Knowledge," cite Russell Barsh as saying that "what is 'traditional' about traditional knowledge is not its antiquity but the way in which it is acquired and used." Our word "tradition" comes from Latin roots that mean something like "giving over" or "handing down." Traditional knowledge is knowledge that is a gift from one generation to the next, a gift we give because we ourselves were given it. I am grateful to my father, in ways that I may never have told him - in ways that perhaps words cannot begin to tell - for the traditions he learned and loved and passed on to me. I'm grateful that he has not let me forget.

There is, of course danger in emphasizing one's heritage and one's roots, especially if we make that the source of a distinction between ourselves and others, or a way of diminishing the lives and traditions of others. Just as much as it matters to me that I am from the people of the waters of the Catskills, it matters to me that my ancestors shared those waters with one another, people from two continents recognizing, each in the other, the waters from which both arose.

For all that I have received, for the traditions like waters pouring over the cliffs, gifts like the Kaaterskill Creek, let me give thanks. Let me give thanks with my life, offering to those who come after me, a taste of the sweetness of those same waters.