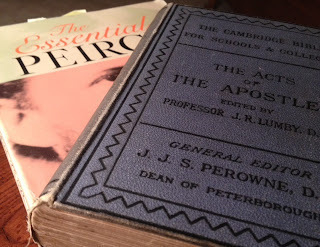

Charles Peirce

Peirce, Religion, and Communities of Inquiry: Jeffrey Howard interviews me for his latest podcast

Recently I had the pleasure of talking with Jeffey Howard on his Damn The Absolute! podcast. We mostly talked about Charles Sanders Peirce, pragmatism (or "pragmaticism" as Peirce called it), religion, and communities of inquiry.

You can listen to our conversation here.

Wicked Problems in Environmental Policy

a. Do so for their perspectives, for their interests, and for their tools.

b. Ask: Who are the stakeholders?

i. Go beyond the financial stakeholders or stockholders.

ii. Include everyone who affects, or is affected by, the policy under consideration.

c. Remember Charles Peirce’s idea: science is the work of a community, not of an individual.

d. Make concept maps, and use other kinds of visualizations of the problems.

i. This is a way of utilizing a broad range of tools. Don’t just use the tools others tell you are relevant; include the arts and the sciences alike.

ii. Drawing and sketching pictures will help you to see better. As Louis Agassiz said, “the pencil is one of the best eyes.” It is often better than a camera.

iii. Music, literature, poetry, and the visual arts may be just as helpful as the tools offered by STEM fields and policy-making professions like law.

iv. If you include the arts, you wind up including the artists; similarly, if you exclude the arts, you exclude the wisdom and insight of the artists.

v. Include ordinary daily practices. Learn to fish, even if you don’t plan to fish. Hike in the woods, even if you don’t like the outdoors. These are, in a way, practices of paying attention to the world.

e. Include other voices and texts in the conversation, not just the shareholders, but all the stakeholders.

f. Define “stakeholders” as broadly as you can. Include a community across generations. Include the departed and the not-yet-born if possible.

i. Traditions might be full of wisdom, so don’t ignore them, especially if they are specific to a place. Traditions may be inarticulate wisdom that is tested by time.

ii. Plan for seven generations. I sometimes think of this as the difference between planting those crops you will harvest this year and planting hardwood trees so that they will be old-growth trees long after you are dead. Humans – and other species – need both kinds of plants.

|

| Bear scat along a salmon river, Katmai Preserve, Alaska |

2) Second, fill your toolbox—and your community’s toolbox—with bear poop. This is an inside reference my students will understand by the end of the semester, but I'll fill you in briefly: I take the time when I am in the wild to look at animal scat, because it is often a picture of what food is available to the animals, and that, in turn, is a picture of the problems the environment is facing. Paying attention to scat over time gives you a long-term picture of changes to the environment. Poop is a tool that is free, that is right in front of you, and that is easy to overlook as unimportant or distasteful. Bear poop that is full of salmon bones tells me one story; bear poop that is full of berries tells me another. I don't literally fill my toolbox with bear poop, but paying attention to negligible things like bear poop gives me new tools I wouldn't have otherwise. What does this mean for us?

3) Third, have what Peirce calls “regulative ideals”

4) Fourth, don’t expect perfection

5) Fifth, do expect growth, and strive to cultivate good things. This is the work of ethics.

6) Sixth, do expect to be part of a community that continues to work on the problems for a long time.

7) And seventh, don’t give up!

The Sentiment That Invites Us To Pray - Peirce on Prayer and Inquiry

Read the rest here, in the latest volume of the Journal Of Scriptural Reasoning.

SPUnK: The Society for the Preservation of Unnecessary Knowledge

James is a Philosophy and Classics major at Augustana University, and he's also the Prime Minister of SPUnK, a campus group I advise at Augustana University.

SPUnK - the Society for the Preservation of Unnecessary Knowledge - is devoted to learning about things we don't need to learn about, because we think unnecessary knowledge is worth preserving and promoting. We distinguish between those things students are told they must study in order to get a job, and those things that we study because there is delight in wonder, and in learning new things, even if we don't yet see their practical use. As both Plato's Socrates and Aristotle pointed out, the love of wisdom begins in wonder, and we seek knowledge not for some simple or material gain but for the satisfaction of wonder and out of a desire to know. Here's Aristotle:

"Now he who wonders and is perplexed feels that he is ignorant (thus the myth-lover is in a sense a philosopher, since myths are composed of wonders); therefore if it was to escape ignorance that men studied philosophy, it is obvious that they pursued science for the sake of knowledge, and not for any practical utility.The actual course of events bears witness to this; for speculation of this kind began with a view to recreation and pastime, at a time when practically all the necessities of life were already supplied. Clearly then it is for no extrinsic advantage that we seek this knowledge; for just as we call a man independent who exists for himself and not for another, so we call this the only independent science, since it alone exists for itself."*Or, as Charles Peirce once put it, science is the practice of those who desire to find things out.**

This is what SPUnK is all about.

James and Hugh will teach you about paper towns, curiosity, education, Abraham Flexner, Albert Einstein, Rubik's Cubes, and other unnecessary knowledge. It's a short interview, well worth a few minutes of your time. Unnecessary knowledge is worth quite a lot more than a little of our time, after all.

* For two places Plato and Aristotle say this, see Plato's Theaetetus 155b and Aristotle's Metaphysics 982b.)

** Peirce writes about this in the first chapter of Justus Buchler's The Philosophical Writings of Peirce.

A Pretty Good Year

As my regular readers know, I'm a professor of philosophy and classics, and I teach a wide range of classes. (You can click on the "Teaching" link above to see a sampling of the courses I teach.)

Often people assume that means I wear tweed and a bowtie and that I spend my time in classrooms talking about old books. All that is true, but it's only a part of what I do.

In fact, most of my favorite classrooms are outdoors, where I'm likely to be found wearing jeans and hiking boots, a parka, or a wetsuit and snorkel.

Over the last dozen years or so my teaching and research have tended towards the environmental humanities. Think of this as the merging of the humanities side of the liberal arts with a close observation of the natural world. I consider my work to be a continuation of the work that Thales and Aristotle did when they paid close attention to animals on the ground and to the skies above, and of the work of Peirce, Thoreau, and Bugbee, all of whom let a rising trout or a solar eclipse provoke philosophical reflection.

While I don't work in an indoor laboratory, I think that education is not about the imparting of information or the filling of an empty vessel with ideas. Education is the kindling of a fire, as Plutarch wrote. And that fire is kindled by the kinds of experiences that we get in labs, art studios, shared meals, liturgies, study travel, and seminars. Lecture halls are a fine place to discuss environmental policy, to be sure. But so is a prairie, especially when you're waiting for water to boil on your camp stove, and watching the sun's beams break over the horizon and melt a light frost on your tent.

When I'm at home, I like to take my classes outside to sit under trees on campus. In the fall, I try to bring my Ancient Philosophy students camping in the Badlands of South Dakota where we can view the stars far from urban glow. Most Januaries, my students and I are in the subtropical forests of Guatemala and on a barrier island in Belize, studying ecology and culture. I rarely take a spring break, since I usually take that week to teach a course in Greece. Last summer I started teaching a class on trout and salmon in Alaska.

Those are all beautiful, memorable places, but I don't visit them as a tourist. I go to these places because I want my students to understand what is at stake when we talk about environmental regulations and practices. I want them to meet displaced people whose permafrost islands are melting or whose forests are being burned down for meager cropland. I want them to see the disappearing mangroves so that they can consider the full cost of seafood. When they stay in homes in Guatemala, my students will meet people who can never again be a mere abstraction; after we return, my students will know that the people struggling to cross borders are not nameless, faceless strangers, but people who are looking for ways to feed those they love.

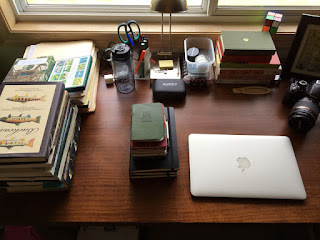

A little less than a year ago I was finishing up a year that had brought me to all these places. I taught in the South Dakota Badlands, in Central America, in Greece, and in Alaska. Along the way, I had begun studying environmental law at Vermont Law School as a way of enhancing my teaching and my research. It was a good year, and as August was winding down, my desk was covered with field notebooks full of observations from Alaska and Guatemala, ready to be written up. My field notes are usually accompanied by thousands of photographs, and hundreds of sketches. I began the fall semester last year ready to teach, and ready to write.

|

| Field notes. A picture of some of the work I do when I'm inside, and not teaching; or, if you like, a picture of my desk as I recover from my injuries. I have a lot of catching up to do. |

And then I wound up in the hospital with some serious injuries. Those injuries put a sudden stop to all my teaching last fall, and for a long time I lost most of my ability to write. (I'll try to write more about the injuries and my subsequent disabilities later; it's not an easy thing to write about yet.)

Now, as this summer hastens towards the beginning of another school year, I am able to look back on last year with a sense of good fortune - albeit mixed with one very bad day and its long-term consequences. Physically, I'm regaining my flexibility and strength, a little at a time. I'm not where I was a year ago, and I may never be there again, but I'm alive and able to walk, so I'll count that in the "win" column of my life's scorecard. Intellectually, most people seem to think I'm doing fine, so I'll also count that as a win. Although it left me exhausted each day, I was able to teach again this spring, and I plan to be back in my classrooms (Deo volente!) this fall.

But here are these field notebooks, and hundreds of unedited pages on my hard drive. It was my habit to write daily. Over the last year, recovering from a brain injury has made it hard to write more than a few sentences at a time.

This morning I was looking at some of my pictures from my research in the Arctic last summer, and I was hit with a feeling of loss. Those photos and those notes should be a book by now, and perhaps several articles and book chapters, too. Instead, over the last year, as I have waited for my body and brain to heal, and as I struggled to do my teaching, I had no strength to write.

It feels funny to say that, but perhaps I am not alone in finding that a brain injury can be slow to heal and extremely tiring. I don't say that to get your sympathy. I am blessed with a very supportive community and an amazing wife who somehow has kept our life together and nursed me through my healing process. I'm fortunate. But if you've read this far, you might consider whether there are others around you who look like they're doing well physically but who might be nursing invisible wounds or who might be struggling to cope with invisible disabilities. This past year has given me a new perspective on that by making me aware of my own disabilities, most of which you won't notice if you see me at the gym or in one of my classrooms.

I might not be able to write another book yet, so for now, here's my plan: I'll write a little at a time. Thankfully, I've got my notes, sketches, and photos. I'll start with them.

If you're curious about how a professor of philosophy and classics does research and writing about nature - and how he works to recover from a serious brain injury - you might check out some of my recent publications. My book Downstream is the result of eight years of field research on the ecology of the Appalachians, with a focus on brook trout. On this blog you'll also find my recently published poem, "Sage Creek," which might give you a glimpse of my ancient philosophy class camping and stargazing in the Badlands. Or feel free to look at my photos on Instagram. Even when I can't teach in the field, I can still wander my garden with a hand lens and camera.

Is Thinking Real? Peirce On Neuro-Determinism

Charles Sanders Peirce, "A Neglected Argument For The Reality Of God."

Giving Our Prayers Feet

Of course, there might be a number of ways in which we might act on our beliefs.

What about prayer? Could praying be a kind of action?

It depends.

Philosopher and atheist Daniel Dennett once described prayer as a waste of time. I mean literally a waste of time. If you're praying, he said, you're not engaged in useful activity. When he was ill, someone offered to pray for him. His reply:

Surely it does the world no harm if those who can honestly do so pray for me! No, I'm not at all sure about that. For one thing, if they really wanted to do something useful, they could devote their prayer time and energy to some pressing project that they can do something about. (emphasis added)I agree with him that if prayer keeps us from doing what we can to alleviate the suffering of the world, we're probably using our time poorly.

On the other hand, as I've argued before, prayer might be essential to other kinds of action.

Giving our money and time is generally a good thing, I think, but I think the giving becomes deeper still when we do as Thoreau urged in Walden: don't just give your money, but give yourself. In other words, if you've begun by dumping water on your head for an ALS icebucket challenge, great. Now deepen that giving by making it part of who you are.

If you decide to do that, prayer - or something like it, I don't care what you call it - can make a big difference. Here's what I mean: giving to charities can be automated, so you can do it without thinking about it. Set up an automatic bank transfer each month and you can give to as many charities as you can afford, without putting much of yourself in it. But if you make those philanthropies and missions the intentional object of your thought for part of each day, you might find that you begin to care a lot more about the cause and the people involved.

If praying is the act of giving some of your time to bring together the world's greatest needs and your greatest hopes, then prayer might be the most important thing we can do. Too often we allow ourselves to divorce others' needs from our hopes, and then the needs of others become allied with our fears.

This is one reason why I respond to the news each day with prayer. Sometimes my prayers are simply Kyrie eleison, "Lord, have mercy." Because sometimes that's all I've got when my heart and mind are overwhelmed. But if that's all I've got, then it will be my widow's mite, and I'll give it. By the way, this has the added effect of making me worry less without taking away my desire to act for goodness and justice.

(My friend Anna Madsen has a short, funny, and helpful piece about just that, by the way. Check it out here.)

All of this was inspired by a moving Facebook post by an alumnus of my college, Caleb Rupert. Caleb is a thoughtful and creative man, and though I don't know him well, he strikes me as a good egg and as someone who wants to do the best he can in this life. Here's what he shared on his page:

I'm standing at the bus stop and on the corner is a homeless woman. A kind looking black gentleman is walking by and nearly walks past her to beak the red-hand count down, 5, 4, 3....The gentleman stops, and turns to the homeless woman. He then falls to his knees and says a short prayer; I cannot hear the words, I'm too far away. As he finishes, she looks up and smiles at him. He smiles back and crosses the street. This gentleman gave up an entire two signals to acknowledge this woman through prayer. Though I do not believe that prayer will be heard by any entity other than the person praying and those around them, this does not discount the power, and importance, of acknowledgement of something as wicked as homelessness. A challenge in which so many of us like to ignore or pretend is non-existence, or worse, pretend this challenge is not as harsh and hard as it is. Regardless of my views of the validity of religion, I cannot ignore the importance of it being an entity which can cause those that follow, truly follow, not just "Sunday believers," but those that acknowledge the importance that every prophet and god-son has preached, which is to care for those that suffer and those that struggle. This gentleman, through his beliefs, gave this woman a smile, and the knowledge that when she goes to bed at night, someone is thinking about her and cares about her well being enough to stop and give his God, which he truly devotes himself to, a mention of her. In the end, regardless of a beliefs validity, what I believe is most important is relieving the pain of those that suffer and always remember that there is always someone who hurts more than you and your acknowledgement is the thing that can save them, even for a brief second, relief from that pain. (Emphasis added)Caleb's words remind me of Thoreau's, and of Dennett's, and of Jesus's. Yeah, you read that right. Because all four of them are concerned with making sure that whatever we do, we act on what we believe, and that we act in a way that tries to make others' lives better.

I asked Caleb if I could share his words here. His reply is just as good as his original post. He said I could post his words, provided I include some links to local food shelves, soup kitchens, and homeless shelters. I love that.

So I will ask that if you share this post, you do the same thing by posting a link to at least one organization in *your* community that helps the homeless. In that way, let us make our prayers effective to the best of our ability, and may they rise to whatever heaven may be.

Here are my links for Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Please consider volunteering your time, giving your money, and remembering them and the people they serve in your prayers. And as you do so, may your prayers grow feet, and begin to change the world.

The Banquet

Union Gospel Mission

St Francis House

Charles Peirce on Transcendentalism, and the Common Good

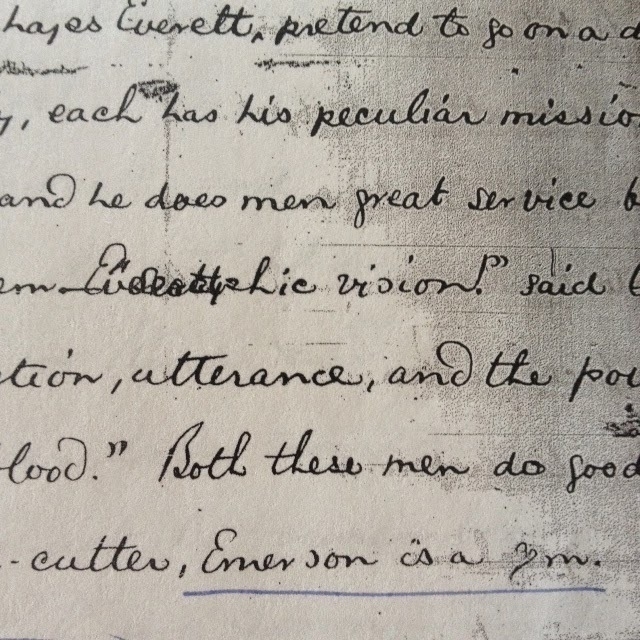

"The devotion to fair learning is not of this rabid kind, but it is more selfish. Antiquity has not accumulated its treasures for me; God has not made nature for me: if I wish to belong to the community of wise men, my time is not my own; my mind is not my own; in this age division of labor is indispensable; one man must study one thing; develope one part of his intellect and, if necessary, let the rest go, for the good of humanity. Emerson, and perhaps Everett [1], pretend to go on a different principle; but really, each has his peculiar mission. Emerson is the man-child and he does men great service by just opening himself to them. "Seraphic [2] vision!" said Carlyle. Everett possesses "action, utterance, and the power of speech to stir men's blood." Both these men do good esthetically. Everett is a gem-cutter, Emerson is a gem." (MS 1633)

|

| A section of MS 1633, dated 1859 |

It's a short paragraph, but it offers considerable insight into the development of Peirce's thought, and it is full of suggestion for our own time.

His claim that a scholar must devote herself to one area only must be taken in the context of Peirce's own studies. Peirce was himself a polymath who wrote on logic, metaphysics, physics, geometry, ancient philology, semiotics, mathematics, and chemistry, among other disciplines.

What he says about learning here is relevant for the ancient tradition of publishing the results of inquiry, and for the contemporary practice of patenting all discoveries. Nature is not a gift from God to the individual researcher. Peirce's invocation of God here calls to mind what he says elsewhere about both God and research. (For more on how Peirce regarded the relationship between God and science, see my chapter in Torkild Thellefsen's collection of essays on Peirce, Peirce in His Own Words.) The idea of God provides an ideal for the researcher, a reason to expect natural research to be productive of knowledge and a reason to believe in the possible unity of knowledge.

(This helps us to understand Peirce's peculiar interest in religion, by the way: he thought religion both indispensable and unavoidable, claiming that even most atheists believe in God, though most of them are unaware of their own belief, because they have explicitly rejected a particular kind of theism while maintaining a steadfast belief in some of the consequences of theism. At the same time, Peirce was opposed to all infallible claims, to the exclusionary nature of creeds, and to what he considered to be the illogic of seminary-training.)

Peirce grew up, as he puts it, "in the neighborhood of Cambridge," i.e. near the home of American Transcendentalism. He says of his family that "one of my earliest recollections is hearing Emerson [giving] his address on 'Nature'.... So we were within hearing of the Transcendentalists, though not among them. I remember when I was a child going upon an hour's railway journey with Margaret Fuller, who had with her a book called the Imp [3] in the Bottle." (MS 1606) His critiques of Transcendentalism have to be read in this context: he was raised among them, with Emerson in his childhood living room and with Emerson's writings being discussed in his school.

Emerson's insight is that nature does speak to those who have ears to hear. His error is in mistaking the relationship of one person to another. Emerson's genius is in perceiving the Over-soul, and his error is in then presupposing the radical individuality of the genius. Peirce does not doubt that there are geniuses. As a chemist, Peirce knew the importance of research and he knew the real possibility of achieving previously unknown insight. Peirce believed, however, that the insight of the genius, or of any serious researcher for that matter, belongs to the whole community of inquiry.

Peirce, who made his living on research, believed that the researcher deserved to earn her living from her work, and he was sometimes frustrated by the chemical companies who took his ideas and patented them, then refused to pay him for them. His ideal - one that is admittedly very difficult to realize - was that all research would be made freely available to the whole community of inquiry. So while the researcher is worth her wages, no one deserves the privilege of hoarding knowledge for private gain. We are all in this together.

******

[1] I'm not sure which Everett Peirce alludes to, but possibly to Edward Everett, who was Emerson's teacher; or Alexander H. Everett, with whom Emerson corresponded.

[2] The word on Peirce's manuscript is difficult to read. I have transcribed this from a photocopy of one of Peirce's original handwritten pages. The word might be "ecstatic" but I don't think it is. See the image above. [Update: Chris Paone wrote to me with the suggestion that the obscured word might be "seraphic." This is a better guess than any I've come up with so far, so until someone has a better idea, I'll take Chris to be right.]

[3] This word is also unclear, and might read "Ink." If you're curious about this, or if you've got some insight about this, write to me in the comments below; I've spent some time trying to figure out what book Fuller had with her, so far with only a small amount of success.

With each of these footnotes, I welcome your feedback and corrections in the footnotes below. Peirce wrote that the work of the researcher is never a solitary affair, but always the work of a community of inquiry, after all.

College Athletics: Cui Bono?

This week I've been considering the place of sports on American university and college campuses. (See here and here for the other pieces I've written on this this week.)

If you grow up here, it doesn't seem at all strange, because it's simply how things are. But a little reflection suggests that the juxtaposition of academics and athletics is a little strange.

I say it is "a little" strange because throughout the ages thoughtful people have said that the two complement each other. Plato's Republic discusses the relationship between gymnastics for the body and philosophy for the mind, for instance. Of course, Plato, famous for his irony, is never wholly straightforward, and the target he is aiming at is probably something else, but the characters in his dialogue act as though bodily exercise and mental exercise are related.

Walking, Playing, and Thinking

One of Socrates' other students, Xenophon, wrote in his Cynegetica that the best education comes through learning to hunt, and that book-learning should only come after a boy has learned the art of coursing with hounds, and practiced it in the country. And there are many others who tell us that moving our bodies and learning go together: Maria Montessori reminds us that the work of children is play. Philosophers as diverse as Aristotle, Nietzsche, C.S. Lewis, Henry Thoreau and Charles S. Peirce tell us that walking and thinking are natural companions.

So the strangeness of the marriage of learning and playing is not the hypothesis that the body and the mind work both need exercise. The strangeness is the way we pursue - or, just as often, fail to pursue - that hypothesis. We are told that movement helps us think, and that playing team sports teaches us virtue. If all that is true, then why do we not encourage all students to play sports?

The Irony: We Do Not Practice As We Preach

Speaking of irony, consider this: What we claim and what we actually do are at odds with one another. We say sports are good for everyone, then we expect coaches to eliminate all but the best athletes from their instruction. Rather than advertising our schools as places where students can get an excellent physical education we expect our coaches to travel far and wide to recruit only the best athletes, i.e. those who need the least instruction and who are most likely to win competitions. It is fairly obvious that, rather than using athletics as a means of inculcating virtue and fostering better thinking, we use athletics to gain honor through victories.

And of course, this is obvious to us. We want to win games because winning is a form of advertising. For good or ill, we accept the fact that high school students will often choose our school in order to participate in the glory of competitions won. But we continue to give the other justifications for participation in athletics, perhaps because we perceive that it would be crass to come right out and say "Come to our college and bask in the glory won by others. It will thrill you, and it might help your job prospects," or "We hope that the victories of our athletes will help us to raise money from people who won't give unless we are winning games."

I don't want to be cynical about this. As I have suggested above and said directly in my previous posts, I'm in favor of athleticism. What troubles me about it is the way that certain college sports become increasingly professionalized. Why, after all, are student athletes considering unionizing? That's something employees do, not students.

Let Everyone Learn To Play

My conclusion is not to push for the elimination of college athletics, but for athletics to be brought more into line with the best reasons for preserving it. If playful exercise makes us better people and better students, then let's urge more students to play. Let's give less attention to inter-collegiate competition and more attention to teaching lifetime sports that will allow our alumni to enjoy the benefits of physical activity for the remainder of their lives. Let's teach poorer students to play golf so that when they enter the business world they aren't at a disadvantage when deals are made on the fairway. Let's teach everyone to swim. Let's take all our students on walks - serious walks, cross-country walks. Let's teach them what Thoreau calls the art of sauntering.

Playful activity takes many forms. We should resist the temptation to think of it as the pursuit of a ball. Swimming, hiking, rock climbing, Tai Chi, dance, yoga, and numerous other activities have the same moral and intellectual benefits as team sports. There should be as many opportunities for vigorous play as there are bodies.

Some of my friends have balked at this, understandably. Not all of us are athletic, or at least not all of us feel athletic. But I think a good deal of this is because many of us learned about athletics in a victory-oriented environment. That environment fosters a narrow and shallow view of the active human life. We may not all be quarterbacks, point guards, shortstops, or strikers, but all of us can be active within the limits of the bodies we have been given. If activity is good for us, then we should treat it as good for all of us. Play should not be limited to the activity of a few for the thrill of the inactive many. Play should be, as Peirce said, "a lively exercise of our powers," whatever those powers may be. And it should be a delight.

Pornography and Prayer

"Repetitive viewing of pornography resets neural pathways, creating the need for a type and level of stimulation not satiable in real life. The user is thrilled, then doomed."Thankfully, "doomed" may be an overstatement. As William James and so many others remind us, our habits make us who we are, so we may be able to form new habits to supplant or redirect old ones. I'm no psychologist, but it seems obvious to me that what we hold in front of our consciousness will synechistically affect everything else we think about and do. So it is no surprise that the author of this WSJ article reports that viewing porn may lead to viewing women as things rather than as people.

To put it differently, everyone worships something, and what we worship changes us. This is one of the good reasons to engage in prayer and worship that are intentional. (On a related note, it's a good reason to forgive, too: forgiveness keeps us from internalizing the pain others have caused us, where it can fester and devour us from within.)

(If you read my writing with any regularity you will recognize these as themes I frequently return to. If you're interested, I've written more here and here.)

One of the problems of philosophy of religion has been to try to identify that which certainly deserves our worship. This quest for certainty has often (in my view) distracted us from the more important work of liturgy, wherein we acknowledge our limitations, including our uncertainty. A good liturgy involves worshiping what we believe to be worth worshiping, while acknowledging our own limitations. After all, if worship doesn't include humility on the part of the worshiper, it is probably self-worship.

Another way of putting this is in terms of love. Charles Peirce wrote about this more than a century ago. There are many forms of worship, many kinds of prayer. Without intending to demean the prayer and worship of others, Peirce nevertheless offers what seems to him to be worth our attention: agape love, the love that seeks to nurture others:

"Man's highest developments are social; and religion, though it begins in a seminal individual inspiration, only comes to full flower in a great church coextensive with a civilization. This is true of every religion, but supereminently so of the religion of love. Its ideal is that the whole world shall be united in the bond of a common love of God accomplished by each man's loving his neighbour. Without a church, the religion of love can have but a rudimentary existence; and a narrow, little exclusive church is almost worse than none. A great catholic church is wanted." (Peirce, Collected Papers, 6.442-443)Notice that Peirce uses a small "c" in "catholic." He wasn't trying to proselytize for one sect; quite the opposite. He was trying to proclaim the importance of a church - that is, of a community that shares a commitment to communal worship - of nurturing love.

I am not trying to moralize about pornography. In fact, I see some good in pornography, just as I recognize goodness in the aromas coming from a kitchen where good cooking happens. Pornography probably speaks to some of our most basic desires and needs, for intimacy, affection, attention, and love, as well as our simple, animal longings.

Still, like aromas from a fine kitchen, porn stimulates us without nourishing us. And by giving it too much attention we may be training ourselves to scorn good nutrition. The WSJ article suggests giving up the stimulation as a means of getting over it. I think this is incomplete without a redirection of the attention to what does in fact nourish us. Prayer and worship that refocus our conscious minds on what really merits our attention can prepare us to receive - and to give - good nutrition. That is, by shifting some of our attention from cherishing need-love to cherishing gift-love - from the love that uses others to the love that seeks their flourishing - we might make ourselves into the kind of great lovers our world most needs.

Spammer, Think Of Your Soul

There are several things that bother me about this. One of the simplest is that I am receiving so many calls and emails that I don't want. The emails are a small bother; my spam filter catches some, and I delete the rest. It's tedious but tolerable. The robocalls are a bigger bother, because they've trained me to no longer answer the phone. Everything goes to voicemail unless I recognize the call as coming from a friend or family member.

But what bothers me most is the exclusion of rational conversation. I would love to be able to tell the spammers and robocallers that I, on principle, do not make impulse buys. I do not respond to any emailed ads, and I never buy something offered to me by a stranger over the phone. Nothing you send my way will interest me. In fact, just sending it my way, unsolicited, elicits the opposite response in me.

There is no way to say this, though. There is no conversation to be had. For a while I did answer the phone, and I asked the callers to remove my number from their lists. Until one caller told me, in no uncertain terms, that he would not do so. "But the law requires it," I protested. "No, you motherf***er," he said, "I will not, and there's nothing you can do about it." I protested again, and he again repeated his coarse epithet. There was no conversation to be had with him, unless I was willing to be his cash-provider. To him, I was not even a potential customer. I was a motherf***er, something not to be conversed with, but to be used for income.

One strong appeal of reason is that it is a substitute for violence. If we both want the same thing, we can reason together about whether it is possible to share resources, to take turns, to seek goods elsewhere. If we have a dispute, we do not need to resort to blows; we can seek a resolution in mutually acceptable terms. But we can only do this if our differences can be mediated by reason. When conversation is cut off absolutely, reason's reach is cut short.

Treating other people solely as means to income rather than as ends worthy of their own consideration independent of my interests cuts off conversation by deciding in advance that these mere means can have nothing to say that is worth listening to.

This angers me. In the ten minutes it has taken me to write this, I have received eight emails, seven of them spam. So I must say it here, even if I cannot say it to those who so mistreat me: I will continue to long for your rationality, for your willingness to remain within the bonds of society. But you must know that the habits of your capitalism are not only illegal but unethical and unkind. Which means that you are cutting yourself off from the people around you, one habit at a time. You may be gaining wealth, but what will you do with it? What will it profit you to gain the whole world and to lose the people around you, to lose your very soul? You may think you are gaining, but with each email sent, with each call made, you are spending a sliver of what makes you part of the community of humankind.

Unwritten

Take the story of a man writing on the ground with his finger thousands of years ago. We do not know what he wrote, we only know that he wrote.

The story is in John’s Gospel, and the scene was this: some men brought Jesus a woman whom, they said, they had caught in adultery.

The passage does not occur in the oldest manuscripts, but it appears in some that are old enough that this pericope has been included in the canonical text.

And it is a delicious passage.

For one thing, it reminds us that even if we have the whole of the Scriptures, we still do not know everything Jesus said or wrote. Or thought.

It is one of the blank spaces in which commentary has not yet been written. Which makes it an invitation to imagine – not to devise religious rules on the basis of conjecture, but to engage in the work of strenuous wonder: what might he have written?

I came up with an answer once, and Merold Westphal put it even better in his book Suspicion and Faith. I won’t spoil it for you by telling you now.

In his writing on Aristotle, Charles Peirce sometimes invokes “that scamp, Apellicon,” the ancient editor of Aristotle's texts. Peirce charges him with altering Aristotle’s texts so that we now must guess at what Aristotle really wrote. (And by "guess" I mean a long and difficult reasoning process involving imagination and testing of hypotheses, not just wild conjectures.)

As I have read Peirce’s manuscripts, occasionally I’ve wanted to curse some unknown scamp who mishandled Peirce’s papers (perhaps Peirce himself) as when he will say “see my note on page 18 of this manuscript” and then I discover that the manuscript is incomplete, ending on page 17.

So I have to guess. What might Peirce have written?

Aldo Leopold wrote about this in his essay “The River of the Mother of God,” which was named for a river on an old map of South America. Some explorer had come upon the river in

the wilderness but did not know where it began or ended, so he drew a short

section of river without beginning or end, leaving it to future cartographers

to fill in the unknown sections.

It’s good to have some mysteries, some lacunae in our

knowledge.

Or rather, it’s good to be aware of some of the gaps in what we know.

As Socrates knew, this awareness of our own limitations is

one of the beginnings of the love of wisdom.

From there, curiosity draws us further on.

Scientia Cordis

"Maximi plane cordis est, per omnia ad dialecticum confugere, quia confugere ad eam ad rationem est confugere, quo qui non confugit, cum secundum rationem sit factus ad imaginem Dei, suum honorem reliquit, nec potest renovari de die in diem ad imaginem Dei."

Berengar, De Sacra Caena. Cited in Charles Peirce, Collected Papers, 1.30. From "The Spirit of Scholasticism," in the first of his 1869 Harvard lectures. Peirce also cites this passage in his essay entitled "Questions Concerning Certain Faculties Claimed For Man."

For Peirce, the genius of Berengar (or Berengarius) lay in pointing out that authority itself must rest on reason, a view that must have seemed "opinionated, impious, and absurd" in his day. (Peirce, Collected Papers, 5.215)(My quick translation: "Clearly it is [a characteristic] of the greatest kind of heart always to seek refuge in dialectic, for to seek refuge in dialectic is to seek refuge in reason; so whoever does not seek that refuge - having been made in the image of God according to reason - abandons his honor, and cannot be renewed from day to day in God's image.")

The standard view of logic was that all premises in logic were either derived from other syllogisms, or from authority. Since syllogisms are made up of premises, it must follow that if we trace our arguments back far enough, all our beliefs must ultimately rest on some authority. This would seem to prove that those who maintain the religious authority are best suited to resolve disputes.

Berengar argued, in his disputation with Lanfranc, that it is through the use of our reason that we imitate God and, in that imitation, are maintained and made new in that image. In simpler terms, if you believe you were made by God, then use the mind God gave you. Dialectic - reason in conversation with itself or with others - is a divinely-given place of refuge from error and confusion. This doesn't mean reason can't go awry; it's just a reminder that giving up on reasoning is not as pious as it might seem at first.

Love One Another: Prisons and Devotion to Enemies

This is a radical idea, one that is like the ideas of Jesus and St Paul that we should love our enemies. If your mind does not stumble over those words, you might be a saint; or you might not be listening to them.

King's argument is that we need our enemies. They need us to make them into the kind of people who embody love, not hatred. And we need - in the depths of our souls - the work of loving them in such a way that we win them over to the side of love and away from the crippling hatred that owns them.

It is easy to say "that's fine for church," or "I will love my enemy in my heart but in my life I will punish him." But what would happen if we thought of our worst enemies - I have in mind criminals and terrorists, the people we most seem to fear - as people with a "heart and conscience" that could be won. As people without whom we are incomplete.

We're good at finding ways to make people pay for their wrongdoing. We have great technology for warfare, and a brilliant system of criminal investigation and prosecution, perhaps the best history has ever seen. I don't propose eliminating those things. Instead, I am asking this: what if we decided that we would put the same creative energy and financial resources that have gone into creating our fine military, police, and courts into winning the consciences of our enemies?

When it comes to our anti-terror policies, I don't see what we can do to win terrorists' consciences, other than living our lives in such a way that anyone who supports our would-be enemies must feel shame at hating such virtuous people. That sounds to me like an end worth pursuing for its own sake, after all.

As for our prisons, our prisons seem to be good at exposing non-criminals to criminals; and to exposing criminals to more criminals, breeding gang culture. Violent criminals surely merit our censure, extraction from society, and punishment. But that doesn't mean our hearts need to be full of a desire for vengeance.

|

| "Peace." Over the head of the angel of peace in Bruton Parish, Williamsburg, VA. |

I believe a society needs to be prepared to use force against those who would forcefully harm others. But increasingly I am coming to believe that individuals in each society also need to be prepared to fight fire not with fire but with the healing waters of love, waters that overflow from hearts that daily struggle to regard the people we most hate and fear as the people we also most need to love. It's not easy. But it may be the only way to become "a community at peace with itself."

So, How's The Sabbatical Going?

Sabbaticals and Long Service Leaves

|

| Sabbaticals can be seasons of letting dry husks bear new life. |

Most jobs in the United States don't offer sabbaticals, but I'm fortunate enough to have one that does. Sometimes my kids chide me for choosing a job with relatively low pay, but self-regulated time is something money can't easily buy. I think I chose my career pretty well.

I say "self-regulated time" because my sabbatical isn't early retirement or a long vacation. My job as a college professor has three basic components: teaching, scholarship, and service. A sabbatical frees me from the first of those components, and from parts of the third. More precisely, it frees me from the daily tasks of teaching and service, but I expect that at the end of this year I will be a better teacher because I've had time to do research and to tear down and rebuild some of my classes. And any college capable of taking the long view knows that faculty who take sabbaticals can render better service over the long haul.

What I've been doing

To the casual observer it probably looks like I've spent a lot of time in coffee shops and airports, and not much else. For the last three years I've devoted myself to teaching and service, giving only a little of my time to scholarship. So when I began my sabbatical my scholarly life felt like deep waters pent up behind a strained dam. Over the last few years I've sketched out five books and seven articles and book chapters. Over my sabbatical I hoped to get maybe one book and a couple of articles done. That may not sound like much, but it's fairly ambitious, given how much time it takes to do the research and to write well.

Since my job description breaks down into the three parts I mentioned above, let me say a few words about what I've been doing this year in each of those areas.

Writing: As for academic writing, so far, I've completed one book (on brook trout), and made significant progress on two others (both on the philosophy of religion). Once I get them done, books four and five are ready to go, too. I've submitted one book chapter for someone else's book, and I'm about to submit another. I've written a few book reviews for popular and scholarly journals, too. Last week I gave a lecture at the College of William and Mary on war and evil. Now I'm preparing that lecture for publication as a journal article. By the time this sabbatical is over, I hope to have at least one book under contract and two more articles sent off for review. I've also done some more popular writing, including a couple of articles on virtue ethics in the Chronicle of Higher Education's Chronicle Review - one on guns and one on the ethics of drones or UAVs. Perhaps most importantly, I've been writing every day. As you can see, I've been trying to write quickly here on this blog a couple of times a week, and I've been writing in a lot of other places as well. Like any other skill, it comes more fluidly with practice.

| ||

| Snail shells grow by slow accumulation, as habits do. |

Service: Even though I'm away from campus, my heart is still there. Everything I do as a professor winds up leaning back towards the classroom, which means towards my students. Nothing I do matters more than the people I do it with and for, I think. I must have written sixty letters of recommendation for students this year (which is more time-intensive than one might think). Sabbatical has also given me the chance to help some colleagues here and at other universities. I've been helping half a dozen friends who teach Classics, Philosophy, and Biology at other universities by reading and commenting on drafts of their essays and books. And I've done a lot of "double-blind" reviewing for six or seven academic publishers who want advice on whether to publish certain books or journal articles. Best of all has been time to collaborate with colleagues in far-off places, corresponding with professors and graduate students around the world about philosophy, ecology, Scriptural Reasoning, Henry Bugbee, Charles Peirce, C.S. Lewis, and other matters close to my heart. I list this as "service" but I could just as well call it "ways I've learned from other people far away."

|

| The license plate on the rental car I had at a recent conference. |

Yes. The word "sabbatical" has its roots in a Hebrew word, shabbath, meaning "to rest." It would be a shame not to use the time to get some rest. Last summer I spent two weeks in a writing retreat sponsored by Oregon State at their Shotpouch Creek Cabin with my friend and co-author Matthew Dickerson. We were working, but what restful work it can be to live, think, and write quietly with a friend. We spent half of each day writing, and the other half talking, hiking, fishing, wading in the ocean. We borrowed some hymnals from an Episcopal church in Eugene and spent part of each evening singing as the sun declined behind the coastal range.

On my way to Oregon, I drove my sons to the coast last summer to look at colleges, to go whale-watching, and to watch some professional soccer matches. When I got home to Sioux Falls, I joined a gym and I became my son's rec league soccer coach. This is his last year of living at home with us, and I can't tell you how grateful I am to have this time with him before adulthood takes him off on the next leg of his life's journey. Despite all the work, and travel, and writing, I've had more time with my wife and my kids, and more time for self-care. I feel much healthier and fitter now than I did a year ago. I have a feeling my family is better off for that, too.

I wish everyone, regardless of their line of work, could have an experience like this every few years. It might remind us all what matters. It's expensive, I know. I took a hefty pay cut from an already modest salary to have this year off, and thankfully our savings have been enough to get us through. (And writing and lecturing makes me a few extra ducats to send to my daughter in college from time to time or to spend on my boys at home.)

No doubt some people will read this and wonder why my college is willing to pay me anything at all when I'm not showing up to work. The answer is that some colleges still take the long view. You have to put aside your monthly planner and get a calendar that measures time and value "not by the times but by the eternities" (pace Thoreau), that looks down the years the way a carpenter holds a plank to her eye and looks down the full length of the board rather than seeing only the grain of what is nearest. Money has been spent on me this year by people who thought it worthwhile to let me stretch from my cramped pose. They have let me drink from distant streams so that I can come back nourished not just by the Big Sioux and the Missouri but by the waters of Oregon and New York and Virginia - and in some sense by the Hippocrene itself.

So that's what I've been doing. I'm sorry I haven't been around campus much. In the long run, what I've been doing should make my return to campus a very good one indeed. I can't wait to tell you more about what I've learned this year once I return.

Guns and Aesthetics

Many guns are semiautomatic - that is, each pull of the trigger fires a round and then loads the next round - without being assault weapons. Most of the duck hunters I know use semiautomatic shotguns, for instance. Their guns only hold three rounds (as stipulated by the law that governs the hunting of migratory waterfowl) but those three rounds can be fired in rapid succession, and most of the guns can be quickly made to hold more than three rounds - usually up to five. Some small-game guns that fire .22 caliber rounds (one of the smallest and least powerful bullets commonly available) are also semiautomatic; and I'd guess most of the handguns sold today are semiautomatic as well. But few of these guns qualify as assault weapons.

|

| Which ones are the dangerous ones? |

I haven't looked into the statistics, but I would guess that most gun deaths in the United States involve semiautomatic handguns and not assault weapons.

Which leads me to the question of whether the aesthetics of guns matters.

My answer is not about what laws we should enact, but about whether aesthetics matters anywhere. And the answer is that every one of us knows that aesthetics always matters. It affects the kind of car we drive, the clothes we wear, the way we wear our hair. Even those who profess that they don't care about these things almost certainly do care. Everyone who studies advertising and marketing knows; songwriters and filmmakers know; everywhere we turn we find a human environment in which we have made important choices on the basis of how the visual aspect of our belongings and edifices makes us feel.

|

| They aren't just vehicles for our bodies, but for all the other things we wish to convey as well. |

The Best View In Warsaw

When the Nazis were retreating from Warsaw they dynamited the city, block by block, leveling nearly every building in the city. After the war, the proud Poles gathered photos and paintings and rebuilt the city, brick by brick, to look just as it had before the war. No doubt this was much harder than simply rebuilding, but they knew: aesthetics matters. It is the expression of people who will not be put down. Visual culture can be used to rally a nation, to embolden hearts, to renew hope.

Years ago, when I was working in Poland, one of my students offered to take me to the top of the Palace of Science and Culture in Warsaw. The building was a "gift" from Moscow, and the building rises from a huge footprint to a soaring tower that overlooks all of Warsaw. When we reached the top and gazed out on the city, Tomek said to me "This is the best view in all of Warsaw."

"Because the tower is so tall that you can see everything?" I asked.

"No," he quickly replied. "It's because this is the only place in Warsaw where you can't see this damned tower!" The building was a "gift" but it was also a visible reminder of Russian Soviet power. Everything from the wide footprint to the dizzying height to the architectural style was an aesthetic expression of domination. The Soviets knew: aesthetics matters. Visual culture can be used to intimidate and oppress.

You Are A Sign

Regardless of what you think of the proposed ban on certain kinds of guns, this should be obvious. Go to a gun shop or a gun show sometime and ask yourself whether aesthetics matters in guns. It might not matter enough to inform our laws, but the guns we make and buy for ourselves ought to tell us something about what is in our hearts. The thing we hold in our hand, like the car we drive and the clothes we wear, is something we project to others, a word we are silently and visibly speaking. As I have written before, the gun is not a neutral element in this speech. It is a word we speak, but it can be a word that speaks us, too. Let me tell you what every polyglot knows: some words in some languages open up new thoughts that you didn't think to think in your native tongue. The technologies we deploy may be the same; as may the visible aspect of those technologies. Nothing is ever neutral; as Peirce said, everything - everything - is a sign, and we ourselves become signs as well.

This doesn't answer the question of what kind of laws we should have. I think that question is secondary to this question: what kind of people should we be?

Pragmatist Scripture: Peirce and The Book of Acts

The Book of Acts has recently come to mind as another strong candidate, for several reasons. I plan to write about all this in more detail soon, but I'll use this space to jot down my thinking quickly, in order to make it available to anyone who might be interested, in the Peircean spirit of shared inquiry.

The Greek title of the Book of Acts is Praxeis Apostolon, or the Deeds of the Apostles. We guess that the author of the text was the same as the author of the Gospel attributed to Luke. The title might well have been added after the book was in circulation for a while, but that's probably inconsequential. It occurred to me recently that this text begins with reminding us that the author wrote a previous book about "the things Jesus began to do and to teach," and then it narrates, without further introduction, the things that the first Christians did after Jesus' death and resurrection.

In other words, it is a book of acts, of deeds. It is a book of narratives about what people did.

Which is to say that it is not primarily a book of prayers, or of songs, or of doctrines. It tells a story, without much attempt to interpret that story. And it is the story of a community learning to work together, and learning how it must adjust its doctrines in light of the community's expansion across and into cultures, and in light of the surprising things they find the new community is empowered to accomplish.

This is appealing to Pragmatists like Peirce, who are more concerned with the way decisions lead to actions than with fixing metaphysical doctrines and whose notions of truth, ethics, and metaphysics are more experimental and transactional than systematic and permanent. Pragmatists are given to the idea that it is good for communities to work with tentative, revisable and fallible tenets, ever striving to improve their practices as the community grows.

*****

Peirce is not exactly easy to read, which helps to explain why most of what he wrote remains unpublished even a century after his death. Nevertheless, the patient reader of Peirce is often rewarded by a writer who took words very seriously.

Some of the words he used to great effect in his lectures and essays are derived from the Book of Acts. Among these phrases are a phrase he uses in his 1907 essay "A Neglected Argument For The Reality Of God," and one that comes at the end of his Cambridge Conference Lectures of 1898. The phrases are "scientific singleness of heart," and "things live and move and have their being in a logic of events." See Acts 2.46 and 17.28 for the sources of these two phrases. (The first one might also have come to Peirce through the Anglican Book of Common Prayer, as I have argued elsewhere.)

Two such phrases are not enough to make the case that Peirce was dependent on the Book of Acts, but thankfully that's not the case I'm trying to make. Peirce was well read and he cited other portions of scripture and, of course, many other books, after all. I only want to suggest that Peirce might have found the Book of Acts to be a scripture that resonates with his Pragmatism.

*****

That being said, I wish to point to one figure in the middle of the Book of Acts who might be taken to be a kind of Pragmatist saint: Epimenides.

I won't belabor that point here, as I have already written about it elsewhere. I'll only add that Epimenides appears to be the unnamed source that St Paul appeals to and cites in Acts 17.28.

Re-entry: Bringing It Home After Studying Abroad

Now let me offer one more step that will make re-entry even more valuable for you. As you journal and reflect on what you saw while you were abroad, take time to look over your journal entries, and ask yourself, What do I want to bring home?

|

| What will you bring home? |

Charles Peirce once wrote, "An American who has never been abroad fails to perceive the characteristics of Americans." Now you've been abroad, and you see things differently. Make your new vision matter. Is there one lesson you can incorporate into your life? One thing you saw abroad that you wish you could have here?

When I've lived in Europe, I've never needed a car, but here in the U.S. I often feel I need to drive even when I'm not going very far. So I've decided to try to walk or bike whenever I can, and to use public transit. It's a small thing, but it makes a big difference for my health, and it might make a difference in the lives of others around me. This is one thing I've brought home.

So how about you? What did you learn? What do you see differently? And what will you bring home?

Drawing Outside The Lines: Marginalia and E-Books

You see, I am an annotator. I draw in books.

Everyone told me when I was a kid that you should NOT draw in books. But I can't help it.

Last summer my sister-in-law, seeing me read with a pencil in my hand, asked me if I always do that. I hadn't really thought about it as unusual until then, but yes, I guess I do. That way my reading becomes a kind of conversation with the book. The author writes, and I write back.

It is becoming a bit easier to annotate e-books, but we have a long way to go, perhaps because we have structured our computers to think in a linear fashion. Computers think in stoichedon, in lines and ranks, like soldiers in formation. Which is a good way to organize information, but it's not the only way, because it's not the only way lines can move. "Idea mapping" or "mind mapping" is another way. This can be expanded to three dimensions or more, as well. Think of a way a line can move and you have another way of taking notes.

Over the years I have devised my own shorthand for note-taking. For some things, I borrow old conventions of abbreviation and expand them, like this:

could - cd

would - wd

should - shd

something - s/t

everything - e/t

nothing - n/t

because - b/c

nevertheless - n/t/l

And so on. Some words, like selah, have entered my annotative vocabulary because they say so much so briefly. (See footnote 3 here, about "selah.")

At times, I've also found it helpful to invent new symbols, pictograms of whole ideas, sentences that can be written a single picture. I can do these with a flick of the pen, but they're much harder to incorporate into a digital text.

I draw lines from one page to the next to connect ideas. I circle names when they first appear in a text so that I can find them again. I draw vertical lines beside paragraphs to quickly highlight long sections of text. A double line emphasizes that highlighting.

I draw maps, and sketch pictures. Sometimes I write in other languages, other alphabets, when those other languages get the idea down more quickly, or more carefully. I haven't written music in books, but I don't see why you couldn't.

And all of that becomes an icon of a conversation. The annotated page is no longer text; it is an image, and a symbol of a set of relations between ideas and authors.

When I was in grad school, José Vericat (who did not know me from Adam) kindly gave me a list of books belonging to Charles Peirce and housed in one of Harvard's libraries. Peirce died in 1914, but his lines and words still illuminate his reading of those pages.

Another bit of scholarly generosity was shown to me a few years ago when I was working on my book on the environmental vision of C.S. Lewis at the Wade Center. The director, Christopher Mitchell, learned of my interest in Lewis's reading of Henri Bergson. Mitchell brought me Lewis's copy of Bergson's Évolution Créatrice to peruse. Every page is covered with marginalia written by Lewis as he recovered from his war injuries.

I think my favorite part of Thomas Cahill's book, How The Irish Saved Civilization, was seeing the facsimiles of marginal paintings - including some racy self-portraits - by monks who copied books in Ireland in the middle ages.

My point in this long blog post? Keep drawing in books. And maybe I'll get another Kindle someday if they can figure out a way to make it easy for me to draw outside the lines. And to preserve those drawings for posterity.