church

- Forgive Onesimus, the indentured servant who ran away, breaking his contract with Philemon;

- Forgive Onesimus for stealing from Philemon as he fled;

- Welcome Onesimus back, not as a slave but as a family member.

∞

A Commercial Company Becomes A Church...And Then A Nation

“When the king and High Church party under Archbishop Laud became masters of the Church of England, many Puritan leaders wished to emigrate. They had property, social position, and an independent spirit. They did not wish to go out to Massachusetts Bay as mere vassals of a company in London. Moreover, they hoped to set up the kind of Church government they liked. Therefore, the principal Puritans of the company simply bought up all its stock, took the charter, and sailed with it to America. A commercial company was thus converted into a self-governing colony—the colony of Massachusetts Bay.”

Allan Nevins and Henry Steele Commager, A Short History of the United States. (New York: The Modern Library, 1956) p.11

∞

On Church Organs and Church Music

Recently I had the good fortune to hear an organ concert in Westminster Abbey. Not long afterwards I heard someone asking whether churches should get rid of their old organs. The question is a reasonable one, since organs are expensive to maintain, nigh impossible to move, and not many people can play them well. To those charges we should add the charge that organs are old-fashioned, and we are not.

I happen to love organ music, so that's one reason why I think we shouldn't get rid of the organs that remain in our churches. But there is at least one more important reason to think carefully about replacing them. Sometimes organs don't fit well with the buildings they are in, as though the organ was purchased on its own merits and not for the way it matched the acoustics of the building that holds it. In those cases, I don't see the loss if they're removed.

But this is a failing of architecture and economics, not just of music. The problem in that case is far greater than the sin of not being contemporary. An organ that does not match the church, or a church that is not made to be acoustically beautiful - both of these are failures, the kind of failure that comes from people who think that design and aesthetics are luxuries. But design is never neutral; it always helps or hurts. Efficiencies and economics can be the enemies of accomplishing the most worthwhile ends.

Here's what Westminster Abbey reminded me of: a well-built organ is not just an instrument; it is a part of the edifice itself. Specifically, it is the part that turns the whole edifice into a musical instrument. When the organ at Westminster is being played, it is not just a keyboard or pipes that are being played, but the whole building. Every bit of the building resounds. The music is not an isolated event anymore; the notes played and the place in which they are played have merged, and each reaches out to affirm the other. A good organ turns a church into a musical instrument.

Too often churches think of aesthetics last, if at all, or refuse to make aesthetics part of their theology. This is a huge mistake. The prophets describe the architectural adornments of the Ark and the Tabernacle and the Temple, giving those aesthetical elements a permanent place in Jewish and Christian canonical scripture. Similarly, the scriptures are full of songs and poems that - one could argue - are unnecessary to salvation. As Scott Parsons and I have argued, art and the sacred belong together. Our faith is not a matter of mere talk; sometimes what must be articulated cannot be said in words, but needs the smell of incense, the ringing of a sanctus bell, the deep bellow of a pipe organ, the beauty of light well-captured in glass or terrazzo.

If you're not sure of what I mean, listen to Árstí∂ir sing the medieval hymn Heyr himna smi∂ur -- in a train station. Can you imagine that being sung in a church with similar acoustics? Here's what I love about the video: when they sing that beautiful old song, everyone around them stops to listen. The beauty of the song is arresting, especially when it is paired with the building. What keeps us from dreaming of building churches, writing music, and designing instruments that could similarly arrest us?

I happen to love organ music, so that's one reason why I think we shouldn't get rid of the organs that remain in our churches. But there is at least one more important reason to think carefully about replacing them. Sometimes organs don't fit well with the buildings they are in, as though the organ was purchased on its own merits and not for the way it matched the acoustics of the building that holds it. In those cases, I don't see the loss if they're removed.

But this is a failing of architecture and economics, not just of music. The problem in that case is far greater than the sin of not being contemporary. An organ that does not match the church, or a church that is not made to be acoustically beautiful - both of these are failures, the kind of failure that comes from people who think that design and aesthetics are luxuries. But design is never neutral; it always helps or hurts. Efficiencies and economics can be the enemies of accomplishing the most worthwhile ends.

Here's what Westminster Abbey reminded me of: a well-built organ is not just an instrument; it is a part of the edifice itself. Specifically, it is the part that turns the whole edifice into a musical instrument. When the organ at Westminster is being played, it is not just a keyboard or pipes that are being played, but the whole building. Every bit of the building resounds. The music is not an isolated event anymore; the notes played and the place in which they are played have merged, and each reaches out to affirm the other. A good organ turns a church into a musical instrument.

Too often churches think of aesthetics last, if at all, or refuse to make aesthetics part of their theology. This is a huge mistake. The prophets describe the architectural adornments of the Ark and the Tabernacle and the Temple, giving those aesthetical elements a permanent place in Jewish and Christian canonical scripture. Similarly, the scriptures are full of songs and poems that - one could argue - are unnecessary to salvation. As Scott Parsons and I have argued, art and the sacred belong together. Our faith is not a matter of mere talk; sometimes what must be articulated cannot be said in words, but needs the smell of incense, the ringing of a sanctus bell, the deep bellow of a pipe organ, the beauty of light well-captured in glass or terrazzo.

[youtube=[www.youtube.com/watch](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e4dT8FJ2GE0&w=320&h=266])

If you're not sure of what I mean, listen to Árstí∂ir sing the medieval hymn Heyr himna smi∂ur -- in a train station. Can you imagine that being sung in a church with similar acoustics? Here's what I love about the video: when they sing that beautiful old song, everyone around them stops to listen. The beauty of the song is arresting, especially when it is paired with the building. What keeps us from dreaming of building churches, writing music, and designing instruments that could similarly arrest us?

∞

It is often helpful to have a sense, at the beginning of a lecture or a sermon, of where it is going. Since many churches are celebrating Palm Sunday today, I want to talk about Jesus’ entrance into Jerusalem on the first Palm Sunday, which marked the end of one kind of ministry in his life, and the beginning of something new in the church. I take yours to be a congregation that is also in a time of transition, so I’d like to offer you some questions to help you think about the next stage of the life of this congregation. In simple terms, I want to take a simple feature from the Palm Sunday story – the palms themselves – and use them as a way of thinking about our vocation as individuals and as congregations.

If you find it easier to follow a sermon when it’s written out, I’ve put the text of this sermon on my blog, which you can find by going to the address on the screen or by googling “slowperc” and “mercy church.” If ever you wanted an excuse to look at your phone during church, this is it. I might ad lib from that script a little, but I’ll try to stick fairly close to it.

Let’s begin with reading the story of Jesus’ entrance into Jerusalem. It is recorded by all four of the Gospels. Here is John’s version:

The story is simple: Jesus came riding into town on a donkey, and people held palm branches as he rode by. Matthew’s Gospel adds that the people laid the palm branches and their own cloaks on the road in front of the donkey.

The Gospels often tell us such stories without telling us what they mean. I imagine that when the Gospels were written, it would have been obvious what this all meant, but since we don’t have city walls, we don’t ride donkeys for transportation, and we don’t have palm trees, the elements of the story are not part of our ordinary experience. That makes it a little harder to grasp what is going on here, which in turn can make it a little harder for us to figure out what the story means for us.

There’s a lot in the story I won’t bother to try to unpack, but I’d like to connect it to how we think about the vocation of a congregation. So for now, let me ask you to hold the Palm Sunday story in the back of your mind, and consider another passage of scripture with me:

We know the body is made of different parts. Each person here has a different set of gifts. One body, many parts; one holy, catholic and apostolic church, many congregations; one congregation, many gifts; one calling, many different ways of answering that calling.

Students at my college often come to me asking me what I think they should do with their lives. I am reluctant to tell anyone what they should do with their lives, but I am always willing to offer them some questions that I think will help them to consider their vocation.

Not all of my students are Christians, or even religious, but I don’t think you’ve got to have a particular religion all sorted out before you can get a sense that your life might be charged with purpose. The questions I offer them are, I think, relevant for everyone. I believe they are also relevant for congregations like this one as you try to sort out your calling.

Of course, there are some common and general directions for all of us who want to follow Christ: We are to love God with all our being, and to love our neighbor as ourselves. We should always do what we can to do justice, to love mercy, and to walk humbly with our God. We are called and commanded to offer mercy, and not just sacrifice. Paul enjoins us to know Christ and the fellowship of sharing in his sufferings, becoming like him in his death and so, somehow, attaining to the resurrection of the dead. Orphans and widows in their distress are our family and we should give them aid and comfort. Jesus offers two simple directions to his disciples in the Gospels: “follow me” and “love one another.” For Christians, there is no escaping these basics.

But these commandments are also vague and general. It is one thing to commit to loving one another; it is quite another to get to work on the actual task of love, here, now, today. Being Christ’s student means taking the general lesson and making it concrete in our lives, putting the theory into practice.

Let’s turn back to the Palm Sunday story now, to consider some of its symbolism. First, Jesus rode a donkey. According to some sources, this was a sign of a king coming in peace. A king coming in conquest would ride a war horse; a king coming in triumph and peace would ride a donkey.

Second, the palms: these could also be signs of triumph, or of the celebration of a king. In the book of Revelation we read:

There it appears that the palm branches were the appropriate way to greet a king on his throne. Perhaps they were also a sign of promise; if you cut down your palm branches, you might be giving up future productivity of your palm trees. You’d only do that if you were confident that you had reason to believe you’d be taken care of even if your trees produced a little less.

Whatever the symbolism of the branches, what we know from the Gospels is that the people who met Jesus coming into Jerusalem honored him with palm fronds. Once again, we live in a different time and place, and we don’t see Jesus literally coming into our city on a donkey, nor do we have palm trees. Nevertheless, Christ dwells among us, and we do have ways of honoring him.

I’ve been traveling a lot in the last few months, teaching in both Central America and Europe. Along the way, I’ve seen a lot of churches, and they’re all a little different. Each one is built using local materials, and decorated in local colors. Each one is designed according to a local style of architecture.

One congregation in Guatemala is full of wooden pews made from the neotropical forest nearby. The doors and windows are often open so the breeze filters through, and the concrete walls make it a cool building in a hot place. I often hear women singing in it as I pass by, and it houses the image of the patron saint of the town, San José, or Saint Joseph the carpenter, an image that seems to inspire a good deal of festivity and local pride.

Another congregation, I like to visit is the tiny Greek Orthodox monastery of Saint Paul in Lavrion, Greece. The ten nuns who live there have built their church with their own hands. The walls are being frescoed with icons, and the colors used in the frescoes come from minerals mined nearby. One nun told me a few years ago that this was a symbol of the way God takes the lowliest things and raises them up for the loftiest purposes. Not many people will ever see this church, hidden on a hillside, but those who do often find it to be a place of holy tranquility and refuge.

In Barcelona, one congregation has been building a church that is taking so long to build that no member who saw it begun will live to see it completed. The very act of construction stands as a rebuke to haste and a reminder that there are things worth doing that will outlast our own lives.

Each congregation has different gifts, different opportunities, different visions. We all share a calling – to enjoy God – but we all have different ways of following that calling. If you have palm branches, then raise them. But if you don’t have palm branches, raise what you have. In the name of Christ churches have raised hospitals, schools and universities, homeless shelters and soup kitchens. They have raised funds for the poor, they have raised their voices against injustice, they have raised issues before legislatures. They have raised gardens for beauty, and vegetables to give away. They have raised children who will love God and their neighbor. They have raised missionaries who will refuse to neglect their neighbors who are far away, and they have raised students who will pursue their calling in their communities and live lives of goodness and love. For many centuries churches have raised artists who will give works of beauty not just to the wealthy but to anyone who would hear or see them. No congregation that I know of can raise all these things, but each congregation has something, some palm branch to raise to welcome the arrival of Christ. What will you raise?

This brings me to my conclusion. I promised you some questions. I’ll ask them quickly here, but let me urge you to continue to reflect on them in the weeks and months ahead.

When my students ask me about what to do with their lives, I ask them three questions, which I will now ask you:

Take time to think about these questions as individuals, and take some more time to listen to one another and affirm one another. Remember that sometimes what we are good at is not something we like to do; and that sometimes the things we like to do aren’t things we are good at. And remember that this is okay. Offer your loves, and your desires to God with thanksgiving.

Remember that just as every person has different gifts and callings, so does every church. We are all called to follow Christ, but the way we follow Christ will depend on who we are, where we live, what we love, and what we are capable of doing. Just as we can ask those questions about individuals, we can ask them about congregations. What is this congregation good at? What does this congregation love? What difference does it want to make in this generation? Take time to offer these questions and the answers you give to God in prayer, with thanksgiving.

In the Palm Sunday story, as in our lives, it is God who enters, God who comes as the peace-bringer, God who brings about the new and surprising and beautiful order of things. The people do not make God enter; we respond to God’s entrance, raising up what we have at hand. Our calling is to use what we have to honor the Lover that has first loved us, the Peacemaker who has brought us peace, the Joyful maker who made us.

Hosanna in the highest!

Palm Sunday and the Vocation of a Church

Mercy Church, Sioux Falls, South Dakota

Palm Sunday, 2015

It is often helpful to have a sense, at the beginning of a lecture or a sermon, of where it is going. Since many churches are celebrating Palm Sunday today, I want to talk about Jesus’ entrance into Jerusalem on the first Palm Sunday, which marked the end of one kind of ministry in his life, and the beginning of something new in the church. I take yours to be a congregation that is also in a time of transition, so I’d like to offer you some questions to help you think about the next stage of the life of this congregation. In simple terms, I want to take a simple feature from the Palm Sunday story – the palms themselves – and use them as a way of thinking about our vocation as individuals and as congregations.

If you find it easier to follow a sermon when it’s written out, I’ve put the text of this sermon on my blog, which you can find by going to the address on the screen or by googling “slowperc” and “mercy church.” If ever you wanted an excuse to look at your phone during church, this is it. I might ad lib from that script a little, but I’ll try to stick fairly close to it.

*****

Let’s begin with reading the story of Jesus’ entrance into Jerusalem. It is recorded by all four of the Gospels. Here is John’s version:

The next day the great crowd that had come to the festival heard that Jesus was coming to Jerusalem. So they took branches of palm trees and went out to meet him, shouting, "Hosanna! Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord-- the King of Israel!" Jesus found a young donkey and sat on it; as it is written: "Do not be afraid, daughter of Zion. Look, your king is coming, sitting on a donkey's colt!" His disciples did not understand these things at first; but when Jesus was glorified, then they remembered that these things had been written of him and had been done to him. (John 12:12-16)

The story is simple: Jesus came riding into town on a donkey, and people held palm branches as he rode by. Matthew’s Gospel adds that the people laid the palm branches and their own cloaks on the road in front of the donkey.

The Gospels often tell us such stories without telling us what they mean. I imagine that when the Gospels were written, it would have been obvious what this all meant, but since we don’t have city walls, we don’t ride donkeys for transportation, and we don’t have palm trees, the elements of the story are not part of our ordinary experience. That makes it a little harder to grasp what is going on here, which in turn can make it a little harder for us to figure out what the story means for us.

There’s a lot in the story I won’t bother to try to unpack, but I’d like to connect it to how we think about the vocation of a congregation. So for now, let me ask you to hold the Palm Sunday story in the back of your mind, and consider another passage of scripture with me:

For we are God's handiwork, created in Christ Jesus to do good works, which God prepared in advance for us to do. (Ephesians 2.10)

We know the body is made of different parts. Each person here has a different set of gifts. One body, many parts; one holy, catholic and apostolic church, many congregations; one congregation, many gifts; one calling, many different ways of answering that calling.

Students at my college often come to me asking me what I think they should do with their lives. I am reluctant to tell anyone what they should do with their lives, but I am always willing to offer them some questions that I think will help them to consider their vocation.

Not all of my students are Christians, or even religious, but I don’t think you’ve got to have a particular religion all sorted out before you can get a sense that your life might be charged with purpose. The questions I offer them are, I think, relevant for everyone. I believe they are also relevant for congregations like this one as you try to sort out your calling.

Of course, there are some common and general directions for all of us who want to follow Christ: We are to love God with all our being, and to love our neighbor as ourselves. We should always do what we can to do justice, to love mercy, and to walk humbly with our God. We are called and commanded to offer mercy, and not just sacrifice. Paul enjoins us to know Christ and the fellowship of sharing in his sufferings, becoming like him in his death and so, somehow, attaining to the resurrection of the dead. Orphans and widows in their distress are our family and we should give them aid and comfort. Jesus offers two simple directions to his disciples in the Gospels: “follow me” and “love one another.” For Christians, there is no escaping these basics.

But these commandments are also vague and general. It is one thing to commit to loving one another; it is quite another to get to work on the actual task of love, here, now, today. Being Christ’s student means taking the general lesson and making it concrete in our lives, putting the theory into practice.

Let’s turn back to the Palm Sunday story now, to consider some of its symbolism. First, Jesus rode a donkey. According to some sources, this was a sign of a king coming in peace. A king coming in conquest would ride a war horse; a king coming in triumph and peace would ride a donkey.

Second, the palms: these could also be signs of triumph, or of the celebration of a king. In the book of Revelation we read:

After this I looked, and there before me was a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language, standing before the throne and before the Lamb. They were wearing white robes and were holding palm branches in their hands. (Revelation 7.9)

There it appears that the palm branches were the appropriate way to greet a king on his throne. Perhaps they were also a sign of promise; if you cut down your palm branches, you might be giving up future productivity of your palm trees. You’d only do that if you were confident that you had reason to believe you’d be taken care of even if your trees produced a little less.

Whatever the symbolism of the branches, what we know from the Gospels is that the people who met Jesus coming into Jerusalem honored him with palm fronds. Once again, we live in a different time and place, and we don’t see Jesus literally coming into our city on a donkey, nor do we have palm trees. Nevertheless, Christ dwells among us, and we do have ways of honoring him.

I’ve been traveling a lot in the last few months, teaching in both Central America and Europe. Along the way, I’ve seen a lot of churches, and they’re all a little different. Each one is built using local materials, and decorated in local colors. Each one is designed according to a local style of architecture.

One congregation in Guatemala is full of wooden pews made from the neotropical forest nearby. The doors and windows are often open so the breeze filters through, and the concrete walls make it a cool building in a hot place. I often hear women singing in it as I pass by, and it houses the image of the patron saint of the town, San José, or Saint Joseph the carpenter, an image that seems to inspire a good deal of festivity and local pride.

Another congregation, I like to visit is the tiny Greek Orthodox monastery of Saint Paul in Lavrion, Greece. The ten nuns who live there have built their church with their own hands. The walls are being frescoed with icons, and the colors used in the frescoes come from minerals mined nearby. One nun told me a few years ago that this was a symbol of the way God takes the lowliest things and raises them up for the loftiest purposes. Not many people will ever see this church, hidden on a hillside, but those who do often find it to be a place of holy tranquility and refuge.

In Barcelona, one congregation has been building a church that is taking so long to build that no member who saw it begun will live to see it completed. The very act of construction stands as a rebuke to haste and a reminder that there are things worth doing that will outlast our own lives.

Each congregation has different gifts, different opportunities, different visions. We all share a calling – to enjoy God – but we all have different ways of following that calling. If you have palm branches, then raise them. But if you don’t have palm branches, raise what you have. In the name of Christ churches have raised hospitals, schools and universities, homeless shelters and soup kitchens. They have raised funds for the poor, they have raised their voices against injustice, they have raised issues before legislatures. They have raised gardens for beauty, and vegetables to give away. They have raised children who will love God and their neighbor. They have raised missionaries who will refuse to neglect their neighbors who are far away, and they have raised students who will pursue their calling in their communities and live lives of goodness and love. For many centuries churches have raised artists who will give works of beauty not just to the wealthy but to anyone who would hear or see them. No congregation that I know of can raise all these things, but each congregation has something, some palm branch to raise to welcome the arrival of Christ. What will you raise?

This brings me to my conclusion. I promised you some questions. I’ll ask them quickly here, but let me urge you to continue to reflect on them in the weeks and months ahead.

1) What is the Sioux Falls equivalent of palm fronds? What do you have at your disposal that you can lay down before Christ to honor him?

2) How do you see Christ the king of peace entering our city? Jesus had been to Jerusalem before Palm Sunday, but on that day he entered the city in a different way. Are there new ways in which Christ is making his presence known to you?

When my students ask me about what to do with their lives, I ask them three questions, which I will now ask you:

3) What are you good at? What do you like? What difference do you want to have made in your life?

Take time to think about these questions as individuals, and take some more time to listen to one another and affirm one another. Remember that sometimes what we are good at is not something we like to do; and that sometimes the things we like to do aren’t things we are good at. And remember that this is okay. Offer your loves, and your desires to God with thanksgiving.

Remember that just as every person has different gifts and callings, so does every church. We are all called to follow Christ, but the way we follow Christ will depend on who we are, where we live, what we love, and what we are capable of doing. Just as we can ask those questions about individuals, we can ask them about congregations. What is this congregation good at? What does this congregation love? What difference does it want to make in this generation? Take time to offer these questions and the answers you give to God in prayer, with thanksgiving.

In the Palm Sunday story, as in our lives, it is God who enters, God who comes as the peace-bringer, God who brings about the new and surprising and beautiful order of things. The people do not make God enter; we respond to God’s entrance, raising up what we have at hand. Our calling is to use what we have to honor the Lover that has first loved us, the Peacemaker who has brought us peace, the Joyful maker who made us.

Hosanna in the highest!

∞

A Visible Sign

This morning my wife, my kids, and I sat around the Christmas tree and opened the gifts we gave one another. Just as we were finishing, my wife's phone rang.

One of her parishioners was coming down from a bad high in a bad way. The police were on the scene, and the whole family was understandably distressed.

I don't know many details, because as a priest she has to keep confidences. All I know is that her parishioners were asking for her to come and help before things got out of hand.

I don't know many details, because as a priest she has to keep confidences. All I know is that her parishioners were asking for her to come and help before things got out of hand.

Which raises the question, "How can a minister possibly help?" She hasn't got a badge or a gun, so she can't arrest people and lock them up; she doesn't have a medical license, so she can't prescribe medications; she isn't a judge who can order someone to be placed in protective custody.

All she can do is be present with those who are suffering. She can listen to those to whom no one else will listen. She can pray with them, helping to connect those who are suffering with words to express that suffering. She can deliver the sacrament, a visible and outward sign of indelible connection to a bigger community, reminding the lonely that they are not alone.

She quickly got out of her pajamas, put on a black shirt and her clerical collar, and picked up her Book of Common Prayer. I kissed her before she went out the door, aware that she was going to a home where there was a troubled family, a belligerent drug user, and eight armed men charged with upholding the law. Oh, boy. "Do you want some company?" I asked, knowing there wasn't much I could offer besides that. She said she'd be fine.

As she left, and the kids continued to examine their gifts, I sat and silently prayed (reluctantly, as always), joining her in her work in that small way.

I admit that I do not like church. I can think of far pleasanter ways to spend my Sunday morning than leaving my house to stand, and sit, and kneel with a hundred relative strangers.

But this is one thing I love about churches: this deeply democratic commitment to including everyone in the community. No one is to be left out. No one gets more bread or more wine at the altar. Everyone who needs solace, or penance, or forgiveness, or company, may have it.

The Book Of The Acts Of The Apostles, the fifth book of the Greek testament, tells the story of the early church as a place where people who needed food or money or other kinds of sustenance could come and find them. Early on in that book we even see the story of how the church made a special office for people whose job it would be to oversee the equitable distribution of food to the poor.

I think highly of my own profession of teaching, because I think it serves a high social good. But I teach in a small, selective liberal arts college. Most of the people I serve have their lives pretty much together. In general, they can pay their bills, they don't have huge drug or legal issues, they have supportive communities, they can think and write well. Yes, most of them struggle with money and other things, but they keep their heads above water, and their futures are bright.

My wife, on the other hand, has a much broader "clientele." She serves the congregations at our cathedral and several other parishes. Her congregants range from the powerful and wealthy to the poorest of the poor. Here in South Dakota more than half our diocese are Native Americans, and many more are refugees from conflicts in east Africa. Ethnically, racially, economically, liturgically, and politically, this is a diverse group.

And again, it is a group where everyone is - or at least ought to be - welcome.

The church has always failed to live up to its ideals. I don't dispute that. Show me an institution that has good ideals and that always lives up to them, and I'll readily tip my hat to it. What I love in the church is that it has these ideals and it has daily, weekly, and annual rituals by which we remind ourselves what those ideals are. We screw them up, we distort and bastardize them, we even sell them to high bidders from time to time when we lose our heads and our hearts. But then we remind ourselves that we should not. And we have institutions and rituals of returning to the path we've departed from.

We will probably always get it wrong. I'm okay with that, as long as we keep turning back towards what is right, as long as we maintain these traditions and rituals of self-examination and self-correction. And as long as we cherish this ideal of welcoming everyone, absolutely everyone. I don't mean just saying we welcome everyone, but I mean doing it.

Again, I work at a small college. Colleges are places where we all talk a good game about being welcoming, and for the most part, we manage to practice what we preach, given the communities we work in. But there's something really remarkable about seeing that ideal at work in a community where there are no grades and no graduation, where the congregation is not just 18-22 year-olds with high entrance exam scores, and where no one gets kicked out for failure to live up to the ideals of the place.

Last night we celebrated Christmas with hymns in two languages.

My wife came home a hour or so after she left this morning. I don't worry so much about her sudden comings and goings as I once did. She gets calls late at night from broken-hearted families watching their beloved die in our hospitals. Will she come and pray with them? Will she come hold their hands for a little while, and be the vicarious presence of the whole church as they suffer? Will she anoint the sick as a reminder of our shared hope for well-being for all people? Will she come to the jail to talk with the kid who has just been arrested, or to sit with his frightened parents? Will she come to the nursing home where they're wondering if this is the last holiday a grandparent will see?

Yes, she will. This is her calling, the work she has been ordained to do. It is the work of love, and I love her for it.

As she walked in the door, I was going to greet her when her phone rang again. I recognized from her conversation that it is a parishioner with memory problems who calls her almost every day to ask the same questions. Sometimes it seems he has been drinking; most of the time it seems he is lonely and afraid. I knew my greeting could wait, and as she patiently listened to her parishioner, I joined her in silent prayer, thanking God for the kindness she shows and represents, a visible sign of the ideal of our community. She cheerfully wished him a Merry Christmas. I think she was glad he knew what day it was.

I don't know how she does it, but she makes me want to keep trying.

One of her parishioners was coming down from a bad high in a bad way. The police were on the scene, and the whole family was understandably distressed.

I don't know many details, because as a priest she has to keep confidences. All I know is that her parishioners were asking for her to come and help before things got out of hand.

I don't know many details, because as a priest she has to keep confidences. All I know is that her parishioners were asking for her to come and help before things got out of hand.Which raises the question, "How can a minister possibly help?" She hasn't got a badge or a gun, so she can't arrest people and lock them up; she doesn't have a medical license, so she can't prescribe medications; she isn't a judge who can order someone to be placed in protective custody.

All she can do is be present with those who are suffering. She can listen to those to whom no one else will listen. She can pray with them, helping to connect those who are suffering with words to express that suffering. She can deliver the sacrament, a visible and outward sign of indelible connection to a bigger community, reminding the lonely that they are not alone.

She quickly got out of her pajamas, put on a black shirt and her clerical collar, and picked up her Book of Common Prayer. I kissed her before she went out the door, aware that she was going to a home where there was a troubled family, a belligerent drug user, and eight armed men charged with upholding the law. Oh, boy. "Do you want some company?" I asked, knowing there wasn't much I could offer besides that. She said she'd be fine.

As she left, and the kids continued to examine their gifts, I sat and silently prayed (reluctantly, as always), joining her in her work in that small way.

I admit that I do not like church. I can think of far pleasanter ways to spend my Sunday morning than leaving my house to stand, and sit, and kneel with a hundred relative strangers.

But this is one thing I love about churches: this deeply democratic commitment to including everyone in the community. No one is to be left out. No one gets more bread or more wine at the altar. Everyone who needs solace, or penance, or forgiveness, or company, may have it.

The Book Of The Acts Of The Apostles, the fifth book of the Greek testament, tells the story of the early church as a place where people who needed food or money or other kinds of sustenance could come and find them. Early on in that book we even see the story of how the church made a special office for people whose job it would be to oversee the equitable distribution of food to the poor.

I think highly of my own profession of teaching, because I think it serves a high social good. But I teach in a small, selective liberal arts college. Most of the people I serve have their lives pretty much together. In general, they can pay their bills, they don't have huge drug or legal issues, they have supportive communities, they can think and write well. Yes, most of them struggle with money and other things, but they keep their heads above water, and their futures are bright.

My wife, on the other hand, has a much broader "clientele." She serves the congregations at our cathedral and several other parishes. Her congregants range from the powerful and wealthy to the poorest of the poor. Here in South Dakota more than half our diocese are Native Americans, and many more are refugees from conflicts in east Africa. Ethnically, racially, economically, liturgically, and politically, this is a diverse group.

And again, it is a group where everyone is - or at least ought to be - welcome.

The church has always failed to live up to its ideals. I don't dispute that. Show me an institution that has good ideals and that always lives up to them, and I'll readily tip my hat to it. What I love in the church is that it has these ideals and it has daily, weekly, and annual rituals by which we remind ourselves what those ideals are. We screw them up, we distort and bastardize them, we even sell them to high bidders from time to time when we lose our heads and our hearts. But then we remind ourselves that we should not. And we have institutions and rituals of returning to the path we've departed from.

We will probably always get it wrong. I'm okay with that, as long as we keep turning back towards what is right, as long as we maintain these traditions and rituals of self-examination and self-correction. And as long as we cherish this ideal of welcoming everyone, absolutely everyone. I don't mean just saying we welcome everyone, but I mean doing it.

Again, I work at a small college. Colleges are places where we all talk a good game about being welcoming, and for the most part, we manage to practice what we preach, given the communities we work in. But there's something really remarkable about seeing that ideal at work in a community where there are no grades and no graduation, where the congregation is not just 18-22 year-olds with high entrance exam scores, and where no one gets kicked out for failure to live up to the ideals of the place.

Last night we celebrated Christmas with hymns in two languages.

Hanhepi wakan kin!That's the second verse of "Silent Night, Holy Night," from the Dakota Episcopal hymnal. We sing the doxology in Dakota, and I'm happy to say that most of the white folks at several congregations in the area have it memorized in Dakota. These are small things, but they might also be big things. If the baby Christ was the Word incarnate, surely little words can make a big difference.

Wonahon wotanin

Mahpiyata wowitan,

On Wakantanka yatanpi.

Christ Wanikiya hi!

My wife came home a hour or so after she left this morning. I don't worry so much about her sudden comings and goings as I once did. She gets calls late at night from broken-hearted families watching their beloved die in our hospitals. Will she come and pray with them? Will she come hold their hands for a little while, and be the vicarious presence of the whole church as they suffer? Will she anoint the sick as a reminder of our shared hope for well-being for all people? Will she come to the jail to talk with the kid who has just been arrested, or to sit with his frightened parents? Will she come to the nursing home where they're wondering if this is the last holiday a grandparent will see?

Yes, she will. This is her calling, the work she has been ordained to do. It is the work of love, and I love her for it.

As she walked in the door, I was going to greet her when her phone rang again. I recognized from her conversation that it is a parishioner with memory problems who calls her almost every day to ask the same questions. Sometimes it seems he has been drinking; most of the time it seems he is lonely and afraid. I knew my greeting could wait, and as she patiently listened to her parishioner, I joined her in silent prayer, thanking God for the kindness she shows and represents, a visible sign of the ideal of our community. She cheerfully wished him a Merry Christmas. I think she was glad he knew what day it was.

I don't know how she does it, but she makes me want to keep trying.

∞

One thing that made the sermon especially strong was its open-endedness: our priest didn't try to apply the sermon to any one social problem, as he could have. Instead, he invited all his listeners to consider whether we'd be willing to have big love remake our lives. In other words, rather than making this into a doctrinal roll-call or a chance to affirm that we all believe the same thing and then move on, unchanged, we were invited to consider, in quiet self-examination, whether we were willing to let love rule in our lives.

One thing that made the sermon especially strong was its open-endedness: our priest didn't try to apply the sermon to any one social problem, as he could have. Instead, he invited all his listeners to consider whether we'd be willing to have big love remake our lives. In other words, rather than making this into a doctrinal roll-call or a chance to affirm that we all believe the same thing and then move on, unchanged, we were invited to consider, in quiet self-examination, whether we were willing to let love rule in our lives.

Part of me really doesn't like church. There's so much about it that bores me, and I usually like sermons least of all. And when I'm not bored, I'm often surrounded by people I don't know very well, shaking my hand and passing a sign of peace. It's an introvert-germophobe's introduction to the doctrine of hell, I guess, so it does serve that theological purpose. I'd prefer a quick nod, some formal bowing, a lot of incense and some well-tuned bells, but you can't always get what you want.

Part of me really doesn't like church. There's so much about it that bores me, and I usually like sermons least of all. And when I'm not bored, I'm often surrounded by people I don't know very well, shaking my hand and passing a sign of peace. It's an introvert-germophobe's introduction to the doctrine of hell, I guess, so it does serve that theological purpose. I'd prefer a quick nod, some formal bowing, a lot of incense and some well-tuned bells, but you can't always get what you want.

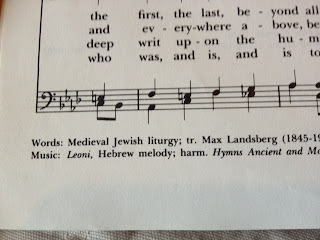

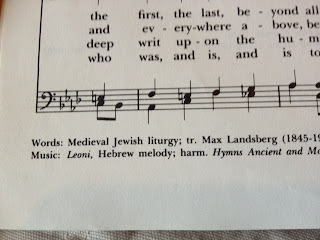

This morning was a pretty good morning. Not only did I hear that excellent sermon that will provide food for thought all week, we also sang a hymn that was translated from a Medieval Hebrew liturgy. Good hymnals and prayerbooks can be bouquets of the choicest flowers of religious poetry. The Book of Common Prayer has often rescued my anguished mind when it cannot find words. Often, when I sing hymns to the room-filling sound of a well-played pipe organ, I find myself wondering how people who do not have a congregation to sing with find opportunities to sing with others. That probably sounds judgmental, but I don't mean it to. I just wish there were more songs sung by people in our daily lives. I suspect the near-universal ownership of iPods is a result of the vanishing tradition of singing together.

This morning was a pretty good morning. Not only did I hear that excellent sermon that will provide food for thought all week, we also sang a hymn that was translated from a Medieval Hebrew liturgy. Good hymnals and prayerbooks can be bouquets of the choicest flowers of religious poetry. The Book of Common Prayer has often rescued my anguished mind when it cannot find words. Often, when I sing hymns to the room-filling sound of a well-played pipe organ, I find myself wondering how people who do not have a congregation to sing with find opportunities to sing with others. That probably sounds judgmental, but I don't mean it to. I just wish there were more songs sung by people in our daily lives. I suspect the near-universal ownership of iPods is a result of the vanishing tradition of singing together.

Can I Ask Questions In Church?

Today I heard a thoughtful, thought-provoking sermon about St Paul's Epistle to Philemon. The heart of it was this: Paul urged Philemon not to claim his legal right, but to lay aside his rights for the sake of the big love that wants to remodel his whole life.

Nobody in their right mind wants that.

Which is why Paul describes that big love elsewhere as foolishness to Greeks - and, he might have added, to anyone else who takes reason seriously.

After all, it's a little bit crazy to lay aside your legal rights for the sake of others. In Philemon's case, Paul was asking him to:

*****

One thing that made the sermon especially strong was its open-endedness: our priest didn't try to apply the sermon to any one social problem, as he could have. Instead, he invited all his listeners to consider whether we'd be willing to have big love remake our lives. In other words, rather than making this into a doctrinal roll-call or a chance to affirm that we all believe the same thing and then move on, unchanged, we were invited to consider, in quiet self-examination, whether we were willing to let love rule in our lives.

One thing that made the sermon especially strong was its open-endedness: our priest didn't try to apply the sermon to any one social problem, as he could have. Instead, he invited all his listeners to consider whether we'd be willing to have big love remake our lives. In other words, rather than making this into a doctrinal roll-call or a chance to affirm that we all believe the same thing and then move on, unchanged, we were invited to consider, in quiet self-examination, whether we were willing to let love rule in our lives.

This is like Mary's approach in John's Gospel, when she tells Jesus "They have no more wine," then tells the servants, "Do whatever he says." She knows enough to know that she doesn't know all the answers. I think our priest was saying something similar today: he doesn't know all the answers, but he's committed to big love, and was inviting us to consider whether we also share that confidence.

To put it differently, he left us with a question to mull over for the week.

Which is often far more helpful than being left with an answer.

*****

Part of me really doesn't like church. There's so much about it that bores me, and I usually like sermons least of all. And when I'm not bored, I'm often surrounded by people I don't know very well, shaking my hand and passing a sign of peace. It's an introvert-germophobe's introduction to the doctrine of hell, I guess, so it does serve that theological purpose. I'd prefer a quick nod, some formal bowing, a lot of incense and some well-tuned bells, but you can't always get what you want.

Part of me really doesn't like church. There's so much about it that bores me, and I usually like sermons least of all. And when I'm not bored, I'm often surrounded by people I don't know very well, shaking my hand and passing a sign of peace. It's an introvert-germophobe's introduction to the doctrine of hell, I guess, so it does serve that theological purpose. I'd prefer a quick nod, some formal bowing, a lot of incense and some well-tuned bells, but you can't always get what you want.

But you do often get what you need, and I think of church the way I think of prayer, or aerobic exercise, or dietary fiber: I need them. Even, and perhaps especially, when I don't want them. And when they are a part of my life, my life feels more whole.

This can be hard to explain to others, so I understand if you think I go to church because it makes me feel good, or because my culture has made it hard for me to think of doing otherwise, or because I feel guilty when I don't go.

I actually feel pretty good when I don't go to church, just like I feel pretty good when I decide to write a blog post instead of going on that four-mile run I had planned.

And so often, when I attend churches, I hear or see things I wish I hadn't heard or seen. These congregations founded on the worship of big love can become gardens overrun by the weeds of uncharitable hearts; some "hymns" I hear are schmaltzy or foolish, or unintentionally (I hope!) promote slavish and unkind ideas about race or gender. At times like that, I'm tempted to give up on "organized" religion altogether.

*****

This morning was a pretty good morning. Not only did I hear that excellent sermon that will provide food for thought all week, we also sang a hymn that was translated from a Medieval Hebrew liturgy. Good hymnals and prayerbooks can be bouquets of the choicest flowers of religious poetry. The Book of Common Prayer has often rescued my anguished mind when it cannot find words. Often, when I sing hymns to the room-filling sound of a well-played pipe organ, I find myself wondering how people who do not have a congregation to sing with find opportunities to sing with others. That probably sounds judgmental, but I don't mean it to. I just wish there were more songs sung by people in our daily lives. I suspect the near-universal ownership of iPods is a result of the vanishing tradition of singing together.

This morning was a pretty good morning. Not only did I hear that excellent sermon that will provide food for thought all week, we also sang a hymn that was translated from a Medieval Hebrew liturgy. Good hymnals and prayerbooks can be bouquets of the choicest flowers of religious poetry. The Book of Common Prayer has often rescued my anguished mind when it cannot find words. Often, when I sing hymns to the room-filling sound of a well-played pipe organ, I find myself wondering how people who do not have a congregation to sing with find opportunities to sing with others. That probably sounds judgmental, but I don't mean it to. I just wish there were more songs sung by people in our daily lives. I suspect the near-universal ownership of iPods is a result of the vanishing tradition of singing together.

When I came home I saw that a friend had tagged me in a post on Facebook, where she shared this article about the importance of continuing to ask big questions. To which I say "amen."

The article raises just this question of whether a decline in attendance at religious services decreases the places in which can we ask big questions:

The article raises just this question of whether a decline in attendance at religious services decreases the places in which can we ask big questions:

"“For anyone who goes to church, these are the questions they are essentially grappling with via their faith,” said Brooks. Indeed, a measurable drop in religious affiliation and attendance at houses of worship may be a factor in the decline of a culture of inquiry and conversation."

I don't know if that's true, and I don't want to claim that the sky is falling because the pews aren't full. But I do find that sitting in the pew helps me, and I think it could be more helpful to more people if there were more sermons like the one I heard today. It's good to ask questions together, and to let the questions do their work.

So I hope that more of us who think that meeting together to pray and sing and reflect on what we believe is a worthwhile practice will do as our priest did this morning, inviting others to turn with him to reflect on the big questions, and the big ideas, and the big love, that - in my case, at least - can keep us from living unexamined lives.

∞

Pornography and Prayer

A recent Wall Street Journal article talks about the way online pornography quickly develops new neural pathways that are difficult to undo. As the author puts it,

To put it differently, everyone worships something, and what we worship changes us. This is one of the good reasons to engage in prayer and worship that are intentional. (On a related note, it's a good reason to forgive, too: forgiveness keeps us from internalizing the pain others have caused us, where it can fester and devour us from within.)

(If you read my writing with any regularity you will recognize these as themes I frequently return to. If you're interested, I've written more here and here.)

One of the problems of philosophy of religion has been to try to identify that which certainly deserves our worship. This quest for certainty has often (in my view) distracted us from the more important work of liturgy, wherein we acknowledge our limitations, including our uncertainty. A good liturgy involves worshiping what we believe to be worth worshiping, while acknowledging our own limitations. After all, if worship doesn't include humility on the part of the worshiper, it is probably self-worship.

Another way of putting this is in terms of love. Charles Peirce wrote about this more than a century ago. There are many forms of worship, many kinds of prayer. Without intending to demean the prayer and worship of others, Peirce nevertheless offers what seems to him to be worth our attention: agape love, the love that seeks to nurture others:

I am not trying to moralize about pornography. In fact, I see some good in pornography, just as I recognize goodness in the aromas coming from a kitchen where good cooking happens. Pornography probably speaks to some of our most basic desires and needs, for intimacy, affection, attention, and love, as well as our simple, animal longings.

Still, like aromas from a fine kitchen, porn stimulates us without nourishing us. And by giving it too much attention we may be training ourselves to scorn good nutrition. The WSJ article suggests giving up the stimulation as a means of getting over it. I think this is incomplete without a redirection of the attention to what does in fact nourish us. Prayer and worship that refocus our conscious minds on what really merits our attention can prepare us to receive - and to give - good nutrition. That is, by shifting some of our attention from cherishing need-love to cherishing gift-love - from the love that uses others to the love that seeks their flourishing - we might make ourselves into the kind of great lovers our world most needs.

"Repetitive viewing of pornography resets neural pathways, creating the need for a type and level of stimulation not satiable in real life. The user is thrilled, then doomed."Thankfully, "doomed" may be an overstatement. As William James and so many others remind us, our habits make us who we are, so we may be able to form new habits to supplant or redirect old ones. I'm no psychologist, but it seems obvious to me that what we hold in front of our consciousness will synechistically affect everything else we think about and do. So it is no surprise that the author of this WSJ article reports that viewing porn may lead to viewing women as things rather than as people.

To put it differently, everyone worships something, and what we worship changes us. This is one of the good reasons to engage in prayer and worship that are intentional. (On a related note, it's a good reason to forgive, too: forgiveness keeps us from internalizing the pain others have caused us, where it can fester and devour us from within.)

(If you read my writing with any regularity you will recognize these as themes I frequently return to. If you're interested, I've written more here and here.)

One of the problems of philosophy of religion has been to try to identify that which certainly deserves our worship. This quest for certainty has often (in my view) distracted us from the more important work of liturgy, wherein we acknowledge our limitations, including our uncertainty. A good liturgy involves worshiping what we believe to be worth worshiping, while acknowledging our own limitations. After all, if worship doesn't include humility on the part of the worshiper, it is probably self-worship.

Another way of putting this is in terms of love. Charles Peirce wrote about this more than a century ago. There are many forms of worship, many kinds of prayer. Without intending to demean the prayer and worship of others, Peirce nevertheless offers what seems to him to be worth our attention: agape love, the love that seeks to nurture others:

"Man's highest developments are social; and religion, though it begins in a seminal individual inspiration, only comes to full flower in a great church coextensive with a civilization. This is true of every religion, but supereminently so of the religion of love. Its ideal is that the whole world shall be united in the bond of a common love of God accomplished by each man's loving his neighbour. Without a church, the religion of love can have but a rudimentary existence; and a narrow, little exclusive church is almost worse than none. A great catholic church is wanted." (Peirce, Collected Papers, 6.442-443)Notice that Peirce uses a small "c" in "catholic." He wasn't trying to proselytize for one sect; quite the opposite. He was trying to proclaim the importance of a church - that is, of a community that shares a commitment to communal worship - of nurturing love.

I am not trying to moralize about pornography. In fact, I see some good in pornography, just as I recognize goodness in the aromas coming from a kitchen where good cooking happens. Pornography probably speaks to some of our most basic desires and needs, for intimacy, affection, attention, and love, as well as our simple, animal longings.

Still, like aromas from a fine kitchen, porn stimulates us without nourishing us. And by giving it too much attention we may be training ourselves to scorn good nutrition. The WSJ article suggests giving up the stimulation as a means of getting over it. I think this is incomplete without a redirection of the attention to what does in fact nourish us. Prayer and worship that refocus our conscious minds on what really merits our attention can prepare us to receive - and to give - good nutrition. That is, by shifting some of our attention from cherishing need-love to cherishing gift-love - from the love that uses others to the love that seeks their flourishing - we might make ourselves into the kind of great lovers our world most needs.