community

Word of the Day: Stammtisch.

Word of the Day: Stammtisch.

A Stammtisch is a table for regulars at a coffee shop or restaurant. It names not just the table but the idea.

There’s something powerful in having a place where you regularly gather with others, a “third place” besides work and home. A lot happens at the water cooler, at the scuttlebutt, at church coffee hour.

Interestingly, many species of animals around the world have something like family reunions. Regular gatherings that reinforce bonds and serve to pass on knowledge to new generations.

We all benefit from the same thing. I’ve read of epidemics of loneliness; breaking bread with others might not be a cure-all for that, but I doubt it could hurt.

It probably shouldn’t surprise us that so many religions have gatherings around something similar: simple meals taken together as a community. As simple as bread and wine, or three palm dates.

I love learning new words, and hoarding them for my writing. I keep a file of good words, and try to include them in everything from my academic writing to my texts. If you’ve got some good words to share, I’d love to learn them!

Poem: Visiting Rowan on Easter Sunday

Emma has been gone for a long time now.

Beside him, an electric photo frame shuffles images of his children and grandchildren and great-grandchildren,

All of whom keep him anchored here.

But he cannot eat, he says, as he holds a white plastic bag

With a blue plastic ring to hold it open for vomit.

We brought him a red egg, hard-boiled, in the Orthodox tradition.

He is glad to receive it with a sad smile,

But we both know he will not eat it.

Mother asks him if he would like communion, and he thinks;

Thinking is hard right now, and his eyes won’t focus

Though he tells us he can see through the doorway beyond

And make out the picture frame in the next room.

We turn to look but we don’t see it,

Unless he means the mirror, or the window, in the room across the hall

Or perhaps he sees something beyond our vision that we cannot yet see.

Richard is coming soon for lunch with his father,

Of course Rowan won’t eat, he tells us,

But he will be glad to see his son.

The phone rings. One of his daughters, calling to check in.

They all check in with me every day, he says,

With a laugh that makes him cough a little.

“They’re so good to me.”

He tells her he has guests, and that everything is fine.

The egg starts to roll off his lap, and he quickly catches it

With his knees, and it does not break.

Which reminds me that he learned to ski in his fifties

And only gave it up in his eighties when his balance started to go.

He hangs up the phone and Mother offers him communion once again.

He cannot focus his eyes, so we read the liturgy for him,

And then he takes the bread with fingers that have grown dark and thin and knurled like wild oak branches.

I am surprised by his speed and agility as he takes the bread.

And he chews it, and drinks the wine,

While his right hand clutches the white bag with the blue ring.

But he does not need to lift it to his lips.

The bread and the wine stay with him, and he laughs,

And stretches out a thin hand to each of us

And thanks us for coming to visit.

Would you like us to shut the door, Mother asks.

He is quick to reply:

No, please leave it open.

And he wishes us a happy Easter,

And we walk out through the lobby, where twenty gray heads in wheelchairs stare at the television screen, and wait.

Charles Peirce on Transcendentalism, and the Common Good

"The devotion to fair learning is not of this rabid kind, but it is more selfish. Antiquity has not accumulated its treasures for me; God has not made nature for me: if I wish to belong to the community of wise men, my time is not my own; my mind is not my own; in this age division of labor is indispensable; one man must study one thing; develope one part of his intellect and, if necessary, let the rest go, for the good of humanity. Emerson, and perhaps Everett [1], pretend to go on a different principle; but really, each has his peculiar mission. Emerson is the man-child and he does men great service by just opening himself to them. "Seraphic [2] vision!" said Carlyle. Everett possesses "action, utterance, and the power of speech to stir men's blood." Both these men do good esthetically. Everett is a gem-cutter, Emerson is a gem." (MS 1633)

|

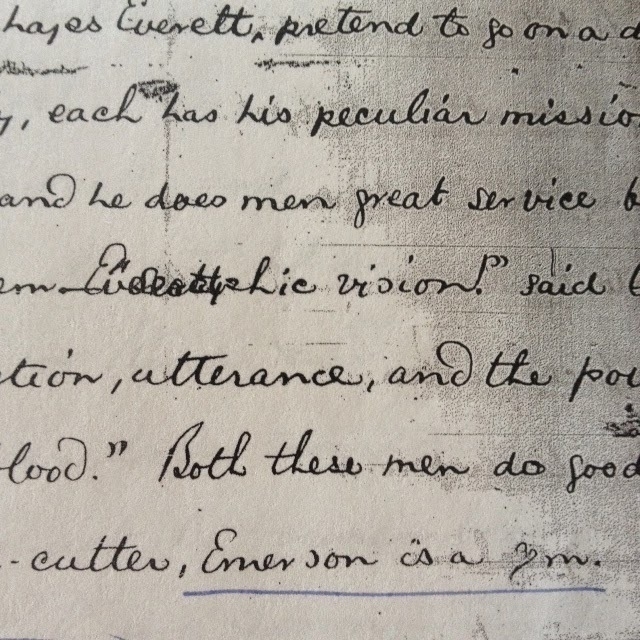

| A section of MS 1633, dated 1859 |

It's a short paragraph, but it offers considerable insight into the development of Peirce's thought, and it is full of suggestion for our own time.

His claim that a scholar must devote herself to one area only must be taken in the context of Peirce's own studies. Peirce was himself a polymath who wrote on logic, metaphysics, physics, geometry, ancient philology, semiotics, mathematics, and chemistry, among other disciplines.

What he says about learning here is relevant for the ancient tradition of publishing the results of inquiry, and for the contemporary practice of patenting all discoveries. Nature is not a gift from God to the individual researcher. Peirce's invocation of God here calls to mind what he says elsewhere about both God and research. (For more on how Peirce regarded the relationship between God and science, see my chapter in Torkild Thellefsen's collection of essays on Peirce, Peirce in His Own Words.) The idea of God provides an ideal for the researcher, a reason to expect natural research to be productive of knowledge and a reason to believe in the possible unity of knowledge.

(This helps us to understand Peirce's peculiar interest in religion, by the way: he thought religion both indispensable and unavoidable, claiming that even most atheists believe in God, though most of them are unaware of their own belief, because they have explicitly rejected a particular kind of theism while maintaining a steadfast belief in some of the consequences of theism. At the same time, Peirce was opposed to all infallible claims, to the exclusionary nature of creeds, and to what he considered to be the illogic of seminary-training.)

Peirce grew up, as he puts it, "in the neighborhood of Cambridge," i.e. near the home of American Transcendentalism. He says of his family that "one of my earliest recollections is hearing Emerson [giving] his address on 'Nature'.... So we were within hearing of the Transcendentalists, though not among them. I remember when I was a child going upon an hour's railway journey with Margaret Fuller, who had with her a book called the Imp [3] in the Bottle." (MS 1606) His critiques of Transcendentalism have to be read in this context: he was raised among them, with Emerson in his childhood living room and with Emerson's writings being discussed in his school.

Emerson's insight is that nature does speak to those who have ears to hear. His error is in mistaking the relationship of one person to another. Emerson's genius is in perceiving the Over-soul, and his error is in then presupposing the radical individuality of the genius. Peirce does not doubt that there are geniuses. As a chemist, Peirce knew the importance of research and he knew the real possibility of achieving previously unknown insight. Peirce believed, however, that the insight of the genius, or of any serious researcher for that matter, belongs to the whole community of inquiry.

Peirce, who made his living on research, believed that the researcher deserved to earn her living from her work, and he was sometimes frustrated by the chemical companies who took his ideas and patented them, then refused to pay him for them. His ideal - one that is admittedly very difficult to realize - was that all research would be made freely available to the whole community of inquiry. So while the researcher is worth her wages, no one deserves the privilege of hoarding knowledge for private gain. We are all in this together.

******

[1] I'm not sure which Everett Peirce alludes to, but possibly to Edward Everett, who was Emerson's teacher; or Alexander H. Everett, with whom Emerson corresponded.

[2] The word on Peirce's manuscript is difficult to read. I have transcribed this from a photocopy of one of Peirce's original handwritten pages. The word might be "ecstatic" but I don't think it is. See the image above. [Update: Chris Paone wrote to me with the suggestion that the obscured word might be "seraphic." This is a better guess than any I've come up with so far, so until someone has a better idea, I'll take Chris to be right.]

[3] This word is also unclear, and might read "Ink." If you're curious about this, or if you've got some insight about this, write to me in the comments below; I've spent some time trying to figure out what book Fuller had with her, so far with only a small amount of success.

With each of these footnotes, I welcome your feedback and corrections in the footnotes below. Peirce wrote that the work of the researcher is never a solitary affair, but always the work of a community of inquiry, after all.

Pornography and Prayer

"Repetitive viewing of pornography resets neural pathways, creating the need for a type and level of stimulation not satiable in real life. The user is thrilled, then doomed."Thankfully, "doomed" may be an overstatement. As William James and so many others remind us, our habits make us who we are, so we may be able to form new habits to supplant or redirect old ones. I'm no psychologist, but it seems obvious to me that what we hold in front of our consciousness will synechistically affect everything else we think about and do. So it is no surprise that the author of this WSJ article reports that viewing porn may lead to viewing women as things rather than as people.

To put it differently, everyone worships something, and what we worship changes us. This is one of the good reasons to engage in prayer and worship that are intentional. (On a related note, it's a good reason to forgive, too: forgiveness keeps us from internalizing the pain others have caused us, where it can fester and devour us from within.)

(If you read my writing with any regularity you will recognize these as themes I frequently return to. If you're interested, I've written more here and here.)

One of the problems of philosophy of religion has been to try to identify that which certainly deserves our worship. This quest for certainty has often (in my view) distracted us from the more important work of liturgy, wherein we acknowledge our limitations, including our uncertainty. A good liturgy involves worshiping what we believe to be worth worshiping, while acknowledging our own limitations. After all, if worship doesn't include humility on the part of the worshiper, it is probably self-worship.

Another way of putting this is in terms of love. Charles Peirce wrote about this more than a century ago. There are many forms of worship, many kinds of prayer. Without intending to demean the prayer and worship of others, Peirce nevertheless offers what seems to him to be worth our attention: agape love, the love that seeks to nurture others:

"Man's highest developments are social; and religion, though it begins in a seminal individual inspiration, only comes to full flower in a great church coextensive with a civilization. This is true of every religion, but supereminently so of the religion of love. Its ideal is that the whole world shall be united in the bond of a common love of God accomplished by each man's loving his neighbour. Without a church, the religion of love can have but a rudimentary existence; and a narrow, little exclusive church is almost worse than none. A great catholic church is wanted." (Peirce, Collected Papers, 6.442-443)Notice that Peirce uses a small "c" in "catholic." He wasn't trying to proselytize for one sect; quite the opposite. He was trying to proclaim the importance of a church - that is, of a community that shares a commitment to communal worship - of nurturing love.

I am not trying to moralize about pornography. In fact, I see some good in pornography, just as I recognize goodness in the aromas coming from a kitchen where good cooking happens. Pornography probably speaks to some of our most basic desires and needs, for intimacy, affection, attention, and love, as well as our simple, animal longings.

Still, like aromas from a fine kitchen, porn stimulates us without nourishing us. And by giving it too much attention we may be training ourselves to scorn good nutrition. The WSJ article suggests giving up the stimulation as a means of getting over it. I think this is incomplete without a redirection of the attention to what does in fact nourish us. Prayer and worship that refocus our conscious minds on what really merits our attention can prepare us to receive - and to give - good nutrition. That is, by shifting some of our attention from cherishing need-love to cherishing gift-love - from the love that uses others to the love that seeks their flourishing - we might make ourselves into the kind of great lovers our world most needs.