Easter

Poem: Visiting Rowan on Easter Sunday

Emma has been gone for a long time now.

Beside him, an electric photo frame shuffles images of his children and grandchildren and great-grandchildren,

All of whom keep him anchored here.

But he cannot eat, he says, as he holds a white plastic bag

With a blue plastic ring to hold it open for vomit.

We brought him a red egg, hard-boiled, in the Orthodox tradition.

He is glad to receive it with a sad smile,

But we both know he will not eat it.

Mother asks him if he would like communion, and he thinks;

Thinking is hard right now, and his eyes won’t focus

Though he tells us he can see through the doorway beyond

And make out the picture frame in the next room.

We turn to look but we don’t see it,

Unless he means the mirror, or the window, in the room across the hall

Or perhaps he sees something beyond our vision that we cannot yet see.

Richard is coming soon for lunch with his father,

Of course Rowan won’t eat, he tells us,

But he will be glad to see his son.

The phone rings. One of his daughters, calling to check in.

They all check in with me every day, he says,

With a laugh that makes him cough a little.

“They’re so good to me.”

He tells her he has guests, and that everything is fine.

The egg starts to roll off his lap, and he quickly catches it

With his knees, and it does not break.

Which reminds me that he learned to ski in his fifties

And only gave it up in his eighties when his balance started to go.

He hangs up the phone and Mother offers him communion once again.

He cannot focus his eyes, so we read the liturgy for him,

And then he takes the bread with fingers that have grown dark and thin and knurled like wild oak branches.

I am surprised by his speed and agility as he takes the bread.

And he chews it, and drinks the wine,

While his right hand clutches the white bag with the blue ring.

But he does not need to lift it to his lips.

The bread and the wine stay with him, and he laughs,

And stretches out a thin hand to each of us

And thanks us for coming to visit.

Would you like us to shut the door, Mother asks.

He is quick to reply:

No, please leave it open.

And he wishes us a happy Easter,

And we walk out through the lobby, where twenty gray heads in wheelchairs stare at the television screen, and wait.

Secular Liturgy

But I've found I need liturgy in my life. Liturgies help me mark seasons. More than that, liturgies create seasons. That's what I really need, because the creation of seasons becomes, for me, a discipline of memory.

Liturgies help me to count my days, which in turn helps me to make my days count.

I used to chafe at the remembrance of birthdays. Why should one day count more than any other? And why should one day seem more a holiday than another?

I'm slowly getting it. There is nothing special about the day; what is special is the use of the day. Cheerless debunkers never tire of pointing out to me that western Christmas is celebrated on a Roman holiday, that Easter is *really* some kind of fertility rite because it's celebrated in the springtime, that all my holidays don't mean what I think they mean because someone once celebrated them in another way. As though the genealogy of the holiday should be its only meaning, as though the celebrations of the past should have magical power over me, as though I had no power to make the days mean something new to me.

And it is true: holidays and liturgies do have power. As I have said before, what we cherish in our hearts we worship, and what we worship we come to resemble or imitate. Holidays are always about remembering, and remembering is cherishing. Of course, we don't all cherish the same things. Memorial Day is, for some, a remembrance of valor and sacrifice. For others, it is a good day for a picnic with family. Both are forms of cherishing, though the thing cherished is quite different.

Much of the difference probably comes from mindfulness and intention, or lack of intention. Everyone cherishes something, but not all of us think about what we cherish. Liturgies help me to cherish mindfully.

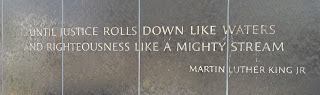

Which is why every April 4th I read or listen to Dr. King's "I Have A Dream" speech, and weep at his loss. And why every July 4th I read the Declaration of Independence. I have set aside days in my year, every year, to read texts like these, texts that have shaped my community. Because these texts aren't done with their shaping. Texts don't hit us once and do all their work; texts seep into us, their words become our words.

Reading and re-reading and reading aloud in communities - these things are like the pouring of water through leaves or grounds - the reading percolates through the words and picks up the essential oils, the savor, the color and taste of the text, and delivers it to us like tea or hot coffee. We taste the words and then the words enter our guts, our veins, our souls.

I recently read an interview with a woman who said "I don't need to go to church to believe those things," referring to her church's beliefs. True. Just as I don't need to go to the gym to get exercise, or to believe that exercise is good for me. But if I don't make a habit of getting exercise, I find I tend not to get what my body needs. The urgent matters in life so easily overwhelm the important ones. Often, when I return from the gym, my wife asks me "How was the gym?" I always think, "It was hard. Everything I do at the gym is difficult." But it is worth doing, because it helps me to maintain my health, and to fight my own decline, to fight the slow slipping away of what I want to hold onto as long as I can. If I do this for my body, why should I not also do it for my heart and mind?

|

| The words percolate through us, and enter our veins. |

I'm not writing this to endorse all liturgies. I'm confident that there are liturgies that celebrate awful things, and that there are participants in liturgies who make poor use of the liturgies they sit through. As with most of what I write here, I'm trying to sort out what I believe, and why -- as another kind of discipline, one of remembering, and of being mindful of what I believe.

The liturgy of Maundy Thursday is not an easy one, because it reminds me of two things I am capable of: I am capable, like Jesus, of washing others' feet, and of living a life of love; and I am capable, like Jesus' friends, of betraying those people and ideals I most claim to cherish and worship. If my worship is only worship in words, I find it easy to forget to worship what is best with my body, with my life. Liturgies - and we all have liturgies - are the ways I remind my whole person to stop and remember what my words claim so easily to believe.