education

- This too is related to technology, of course. If the class is focused on video screens, then all the chairs will face the screens, and the classroom might even be structured like a theater. Etymologically, "theater" means something like "a place of gazing," and theaters tend to encourage people to gaze. Sometimes this can work against other activities, like colloquy, small-group interaction, and really anything that involves students moving from one place to another.

- If that last sentence made you ask,"But why do you want your students to move from one place to another?" then you see that we have some pretty strong presuppositions about how education should happen: students should sit and listen, teachers should stand and lecture. This communicates something about authority, and at times that's helpful. But it can also invite students to lean back into passivity, and to assume they have no role in their own education.

- The furniture in classrooms tells us how people are to behave, because it has been made and purchased by people who had in mind some idea of how students should behave. Most wrap-around desks are made for right-handed people, for instance. And most classroom desks I've seen expect students to sit upright, at attention, with a book open in front of them. I really don't like those desks, and I feel trapped when I sit in them. I wonder sometimes how they make my students feel. I wish we had fewer chairs and more sofas. Maybe a fireplace, or some tables with glasses of water, and ashtrays on them. I suppose I wish I could teach in pubs or ratskellers, which are, after all, places consciously designed for people to meet and discuss what most matters to them, informally, passionately, amicably.

- Classrooms that privilege video screens tend to undervalue natural light and windows. I am reminded of Emerson's reflection on a boring sermon he once heard. Emerson wrote, in his Divinity School Address, that while the minister droned on, Emerson looked out the window at the falling snow, which, he proclaimed, preached a better sermon than the minister. I have no doubt that nature can often give a better lecture than I can.

- Support good schools. One of the best defenses against a nation falling apart is a well-educated populace. People who are able to think for themselves are less likely to let others do their thinking for them, which is one of the surest defenses against abdicating to a tyrant. People who know their rights and their history will be well-prepared to fight to defend them. People who only know how to fight but don't know what they're fighting for promote instability in government.

- Promote economic opportunity for everyone. We celebrate Dr. King as a promoter of equal rights, but it's worth remembering that for him those rights were closely tied to the opportunity to exercise them and to help one's family to flourish.

- Encourage bright people in your community to become teachers. Public school teachers play too important a role for us to not want our brightest minds in our classrooms. I'm not just talking about STEM fields, either. Literature, history, social sciences and arts are the disciplines that shape our imaginations. Without good art and good stories, you don't have a nation, period.

- Subscribe to your local newspaper. Here are two of the most important professions for any democracy: law and journalism. Without defense attorneys to defend rights, equal rights don't mean much. And without investigative journalism, power will corrupt governors unchecked. Your subscription is your share of the paycheck of people who will watch the custodians of the state. There's not much more important than that.

- The trust they've placed in their community. Think about it: if your parents or your pastor or someone else you trusted taught you that there's an irreconcilable conflict between science and faith, you might distrust anyone who said otherwise. It might help such students to go back to that community and ask the question I posed above. This may take time, because there's a lot at stake here.

- An even bigger concern is the question of human dignity. I think that's what's behind the old complaint that "I'm not descended from monkeys." If the student is simply concerned about being descended from unwashed furry critters, they should probably look more closely at their family trees. Monkeys are often nicer than our actual relatives.

- But there's another concern here that's actually quite positive, because it means that they care about ethics, and they're trying to preserve that in the face of a perceived threat. Some students correctly intuit that what's at stake in evolution is not merely a theory of descent but a whole theory of knowledge, and of metaphysics. Natural sciences rest upon an assumption of methodological naturalism. That is, they assume that it is possible to explain natural phenomena by appeal to nature and nothing else. So far, so good. But sometimes we then make a little leap to saying that therefore whatever naturalism cannot explain is unknowable or nonexistent. This is not just naturalism but a kind of reductionistic naturalism, and it's tricky territory, because it might imply that there is no real basis for ethics, or for valuing others' lives. I'm not saying we're not free to value others' lives; I'm just saying that some of these students want to believe that there are good reasons to expect everyone to value everyone, not merely a world of subjective interests. And many of them are reasonably suspicious that reductionistic naturalism cannot itself be supported by science; after all, how could natural science prove that what it can't see isn't there? Such claims sound a bit like the misdirection of Wizard of Oz: "Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain!" We'd be better off avoiding such claims, both because we cannot prove them and because they do a disservice to science.

Hope And The Future: An Open Letter To The President

I know you've got a lot on your mind right now, and I don't envy you the burdens of your office. I pray for you often, asking God to give you the wisdom to make good decisions and the strength to carry them out.

I have two requests for you today. The first is, please don't give up on hope. In your first campaign you spoke about hope a lot, and I think you know that meant a lot to people everywhere. We all want hope, especially hope that we feel we can believe in. We will often settle for unreasonable hopes, but we prefer hopes that seem grounded in possibility rather than in wild fantasy. For a while there you sounded like you had both hope and reason for hope. When I think about the office you occupy, I imagine there's a lot that works to rein hope in, to tame hope and to break it. You start out with big ideals, and then everyone reminds you that limited resources will be made to seem even scarcer by partisan quarrels until there's nothing left to spend on dreams. But let me tell you this: we need you to make lots of small decisions, but we also need some big dreams, some reasonable hopes. We need someone who will climb the steps to the bully pulpit and preach a sermon that reminds us of "the better angels of our nature." Don't just make the little decisions; remind us of the great hopes that have lived in our nation.

I have two requests for you today. The first is, please don't give up on hope. In your first campaign you spoke about hope a lot, and I think you know that meant a lot to people everywhere. We all want hope, especially hope that we feel we can believe in. We will often settle for unreasonable hopes, but we prefer hopes that seem grounded in possibility rather than in wild fantasy. For a while there you sounded like you had both hope and reason for hope. When I think about the office you occupy, I imagine there's a lot that works to rein hope in, to tame hope and to break it. You start out with big ideals, and then everyone reminds you that limited resources will be made to seem even scarcer by partisan quarrels until there's nothing left to spend on dreams. But let me tell you this: we need you to make lots of small decisions, but we also need some big dreams, some reasonable hopes. We need someone who will climb the steps to the bully pulpit and preach a sermon that reminds us of "the better angels of our nature." Don't just make the little decisions; remind us of the great hopes that have lived in our nation.The second request is related to the first: I'd like you to help us to nurture the reasonable hope that we can find new ways of making energy. There are powerful sermons being preached about building more oil and tar sand pipelines so that the old ways can be maintained. But those are sermons without hope, the sermons of a creed doomed to perish in fire and smoke of its own burning, the platitudes born of a faith in a limited and dwindling resource. They are the cynical homilies of those who pass the collection plate and who think the worst thing they can lose is our regular tithing to the god of petroleum.

We need a reformation in that way of thinking.

Because national security is not just about defending ourselves with bullets and bombs, and it's not just about making sure we have enough oil. In the long run, national security has to mean that we have taken good care of the land, so that it is still worth inhabiting. That, in turn, means we have nurtured our hearts and minds and cultivated our virtue. What, after all, does it profit a nation to gain the world and lose its soul? We are a nation of innovators, not just custodians of the status quo. We began as an experiment, and it is in experimentation and new thinking that our hope now lies.

We can begin by directing more funding to universities. We need bright engineers who have the freedom and funds to investigate how to make more efficient solar and wind energy.

We also need bright students in the humanities who will help us form the best policies to make sure we use our technology well. After all, a democracy can live without engineers, but it cannot survive long without reporters, teachers, and lawyers.

We know that money spent on education pays a perpetual dividend to both the person educated and her whole community.

We can also encourage the creation of new and important prizes. Why should we not have more prizes like the Nobel Prizes? And why shouldn't such a proud and wealthy nation fund some of those prizes? You've got the ear of the world for a little while longer. Use that opportunity well, and urge us to put our private funds into prizes for people who advance the causes that matter most to humanity: growing good food, creating and preserving clean water, protecting the species God told us to care for, healing the sick, liberating captives, and making us better producers and consumers of energy.

I am grateful for people who willingly take on the burdens of public office. I don't imagine it is easy. You remain in my prayers.

David

The Best Watchmen Of Our Thoughts

Plato, Republic 560b. Allan Bloom's translation. (Basic Books, 1991)

The Importance of Struggling to Understand

"I don't like obscurity and obfuscation, but I do like dark sayings I must leave the clearing of to time. And I don't want to be robbed of the pleasure of fathoming depths for myself."

Robert Frost, "On Emerson." In Selected Prose of Robert Frost. Hyde Cox and Edward Connery Lathem, eds.(New York: Collier, 1968) p.114. (Originally delivered as an address to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences on the occasion of Frost's being awarded the Emerson-Thoreau Medal. Later published in Daedalus, Fall 1959.)I like Frost's use of "clearing" which still echoes the older meaning of "clear," that is "brighten." Frost's point is also excellent: simply explaining poetry, or great texts, to students is not enough. It is often helpful to guide them and to show them hermeneutical tools, or to speak with them about how we ourselves have grappled with texts, but we should be careful about the temptation to explain, since explanations can rob students of the pleasure of discovery. Poetry has immense value for us, and one -- just one -- of its benefits is the way that it can become the means by which we learn to solve problems that we have never encountered before.

Teaching Outdoors

|

As early as middle school I knew I wanted to become a college professor, and I love my job. It is a delight to spend time with young people who are curious, after all.

Years ago, my friend Matt Dickerson pointed out to me that it's also my job to help those who are not curious to see why they should be. As it turns out, that work is usually delightful, too, a rewarding challenge.

So on the whole, I love my work.

But I admit I don't love classrooms, for several reasons:

First, no matter what decade, every classroom I've been in has exhibited an unhealthy tendency towards becoming cluttered with the latest technology, and most of that tech seems to take up a lot of space and to become the center of attention. I'm not opposed to technology in the classroom, not at all. But I'm opposed to letting it get in the way, as it does when the "Smart Cart" leaves me no room for my lecture notes, or when I can't seem to turn the ceiling-mounted projector on or off. I'm a fan of chalk, because chalk allows spontaneity, and it allows for much more than alphanumeric writing in neat rows. Sadly, concerns about chalk dust getting into computers is threatening to make chalkboards disappear from my classrooms. Alas. Chalk is an excellent technology, and if it vanishes, I will mourn its loss.

Second, classroom architecture is not some value-free, neutral design. Classroom architecture makes a big difference in how people teach, and how they learn:

|

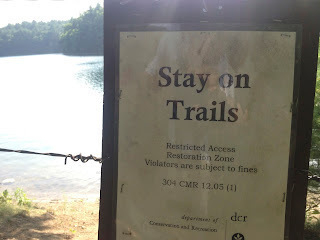

| Step off the trails! Explore! An ironic sign at Walden Pond. |

And this is why I am a preacher of the importance of study abroad. Not just travel, but serious, engaged, rigorous study in the classroom of life in another place. This is why I teach Classics in Greece every year, and why year after year I take students to Central America to study environmental philosophy and ecology.

More and more I've been trying to shift the learning focus in my classes from the classroom to the laboratory - where by "laboratory" I mean anywhere that allows students to learn with their whole person. I make my ancient philosophy students devote hours each semester to star-gazing, in part because this is what the ancients did, and in part because I don't want them to miss the stars. I want them to gaze in wonder at the firmament so that when they read Aristotle and Galileo they know that they've looked at what those great minds saw as well. We even occasionally take field trips to really dark places like the South Dakota Badlands so we can see the skies even better.

My environmental philosophy students must observe a square meter of earth for a semester, spending an hour at a time without a camera, drawing and writing about what they see, because it does not make sense to me to talk about the earth when you have not taken the time to sit upon it, to listen to it, to smell and taste it, and to see what other lives creep, and walk, and fly across it.

My friend Aage Jensen advocates the Norwegian philosophy of Friluftsliv, life and education outdoors. And when he organizes a conference on it, he eschews conference centers and holds the conference while walking through the mountains, or paddling a river. Because he believes that one should practice what one preaches, and that nature is always ready to teach.

To paraphrase the Stoic Musonius, teachers would do well to talk less and to take their students with them into the fields, because there they will learn far better and far more than in the lecture hall.

|

| Nature is full of things worth seeing. |

Back To Work

I've been on sabbatical for the last academic year, and it has been a gift.

I've done a lot of writing (I think I've averaged about 750 words a day, which may not sound like much, but it is) and a lot of reading (roughly a half a book a day for fifteen months) and a lot of traveling (visited five countries; had one writing fellowship on the west coast and one NEH study fellowship on the east coast; read and wrote at a writer's conference in Vermont; attended a handful of other conferences; and a whole lot more. I lived out of my suitcase for the first two months of this summer.)

In other words, my sabbatical hasn't been idle time. Quite the opposite.

But now I'm ready to get back to work. To the work I feel called to do, that is. All the work I've done for the last year has been aimed at a particular purpose: to make me a better teacher.

Those Who Can, Teach

No doubt you've heard it said that "those who can, do; those who can't, teach." Anyone who has tried to teach well knows exactly why that saying is false.

In one small way, it can sometimes be true: it may be that the teacher lacks the physical capability to perform the tasks she teaches. But if she teaches them, she must understand them at least as well as those who perform them. Good athletic coaches illustrate this idea well: a man may be a brilliant football coach well after he's too old to survive being tackled; a woman may understand her sport far better after her body will no longer allow her to participate in it.

But in each case it is obvious that the teacher has some mastery that is greater than the bodily capacity to do the activity.

To paraphrase Aristotle: the craftsman knows something, but the one who teaches the craftsman must know even more. My sabbatical has been a chance to deepen precisely the kind of knowledge I need to be a good teacher.

Be The Change You Want To See In Your Students

I can't speak for all teachers, but I find that it is not enough to know only as much as I plan to teach. When I teach a course in philosophy, philology, theology, ecology, or history I must become a student of that discipline myself.

This is one of the reasons why humanities professors are always reading and writing. It is not enough to tell the students what we know. As Plutarch put it, "The mind is not a vessel to be filled but a fire to be kindled." My job is not to impart information; my job is to make students. My job is the work of conversion, of helping people become what they were not, of facilitating the habit of learning throughout one's whole life.

To put it negatively, my job is to avoid being a hypocrite. More positively, my job is to be an example of the kind of change I wish to see in my students. And this is why sabbaticals are so important. They are not a reward for service, a respite from the work of teaching. They are a chance to immerse oneself in the life of the student again, to strengthen the scholarly habits. Sabbaticals make better teachers.

Looking Forward To My Real Work

Recently I was having a drink with some other professors in my field as we sat on a hotel rooftop in Athens. Several of them described the tricks they've come up with to minimize grading and teaching, so that they can spend more time on their "real work." This "real work" turned out to be their research.

Recently I was having a drink with some other professors in my field as we sat on a hotel rooftop in Athens. Several of them described the tricks they've come up with to minimize grading and teaching, so that they can spend more time on their "real work." This "real work" turned out to be their research.Kvetching in bars is a popular pastime for many professions, so I won't hold those words against them. And I can't claim to know what the difficulties of their lives are like, nor how hard it is for them to manage the stresses of the job market (neither of them has a stable position). And both of them may in fact be excellent researchers who are producing books and articles the world needs.

But it made me sad to hear that things have so fallen out for them that they have come to regard teaching as an impediment to their real work. I love teaching, and I'm grateful for the privilege of spending time with books and pens and bright young minds. I love the way the books and pens become tools for working out our life together.

Some of my friends have been ribbing me about having to go back to work after a yearlong sabbatical. I'm sure it will present some challenges, and I'll have less control of my schedule. But honestly, I've missed the classroom. This year has been like time in the shop, taking apart the engine and replacing worn parts, topping off the fluids, recharging the battery. As the sabbatical comes to a end, I find I'm eager to rev the engine and step on the pedal. I'm looking forward to seeing my older students, and to meeting the new ones. I'm looking forward to engaging in the lofty work I've been called to, of helping young people think in ways they had not yet imagined. I'm looking forward to seeing their eyes light up as they read Plato and Kant and Emerson, to hearing their challenges, to seeing what happens when they, too, step on the pedal and squeal the tires. I can't wait to get back to work.

*****

If you're curious: The Plutarch quote, above, comes from near the end of his "On Listening To Lectures." This is my rough translation, which I think comes pretty close to what he says.

Against Grading

We are sick with love of enumeration. We've discovered that counting things over time is a powerful way to predict what will happen next. And now we are mantic-obsessives, (that's not a typo) that is, people obsessed with prediction, with foresight that will rule the uncertainty of our lives.

Look: that's not such a bad thing, in a way. What I'm describing is the root and trunk of science: quantification and statistical analysis is the beating heart of our understanding of scientific laws, which are about predictive inference. Understanding of the laws of nature can save lives, and make water clean, and heal some deep wounds. Science is wonderful, and no liberal education should stint in its science offerings.

But if we're not careful - if we divorce science and enumeration from other ways of regarding value - that can make some pretty big holes in the world, too. (Whenever I hear someone say that religion is the cause of human suffering, I think "What about chemistry?" Both religion and chemistry can be deployed to change lives, and to change them dramatically. Or to end them suddenly.)

Likewise enumeration. The counting of things can give us great power to rule our own futures. It can also give us great power to rule the futures of others, and not always in kind ways. One real danger of learning to count things is that we find it too easy to shift from saying "It's hard to count X" to saying "X doesn't count."

Our quantifimania, for instance, has half of us (no, I didn't count, I'm speaking figuratively) believing that good teaching can be measured by test scores. Or that someone's intelligence can be reduced to a simple number. Or that a kid's giftedness, or ability to learn, or likelihood of living a creative and thoughtful life can be simply reduced to a GPA or a standardized test score.

Years ago, when I was thinking about beginning my graduate studies in Philosophy, a professor I knew suggested I prepare for my Ph.D. by attending St John's College's "Great Books" program. I looked over the reading list and realized that even if it didn't get me into a Ph.D. program, it would be worth it for its own sake.

As an undergraduate at an elite liberal arts college in the northeast, I was continually reminded that little mattered more than my grades. I was the sort of student who earned good grades with little effort, so it was natural to begin to believe that what mattered most came without struggle. As a result - I realize this now, in hindsight - I bypassed much of the opportunity my college offered me by studying only what my classes required of me.

This all changed in my first term at St John's, when I wrote a seminar paper on Aristotle. My tutor Matt Davis returned it to me without a grade on it. Instead, it was covered with marginal comments, underlining, and a paragraph of reflection and response at the end. But again, no grade. "How did I do?" I asked him. "Have a look at what I wrote," he replied. Sure enough, he told me how I did: here were the things that were strong; here were the gaps in my argument. No quantification, just explanation.

I wanted a grade because I'd been habituated to thinking of the grade as the way of judging the merit of my work. St John's decision to refuse to give grades is an intentional and hard-fought resistance to that way of thinking.

At the end of the term, each of my tutors gave me one, two, or even three pages of handwritten comments on my strengths and weaknesses as a student. But once again, no grades. Nothing to distract me from reading their comments, nothing that would allow me to measure the worth of their comments other than the comments themselves. And nothing to make me think: "Well, that's done."

As a result, I stopped thinking about grades and started thinking about ideas, and texts, and writing. I started caring more about correcting my ignorance than about concealing it from my peers and teachers. And I stopped thinking about learning as something that happens in fifteen-week segments. Learning was no longer something that begins here and ends there. Learning was now a river I step into, and in which I may swim, and bathe, and drink for as long as I am able. And if I step out, it remains there, ever flowing, for me to return to.

It was only then that I realized just how bored I had been in school. I had been bored since my childhood, because I had to show up, had to perform tasks, in order to get these lofty numbers that weighed so heavily and meant so little to me personally.

I've known many students who are bright but who don't do well on standardized tests. I've known many others who don't do well on any test at all, and I've no doubt that much of it has to do with anxiety over the way their work will be reduced to a number, one they feel is so disconnected from what they know. As a teacher I feel I'm constantly fighting to get my students to stop worrying about their grades, even while I'm required to assign grades to their work. Grades are, in my opinion, one of the worst things to happen to education. This is not to say I'm against evaluation or helpful feedback. I'm all for them, in fact. Which is why I'm so opposed to the damnable, lazy practice of reducing that evaluation to what can be easily counted.

The ancients tell us that King David sinned against God by counting his fighting men. (Here, too.) I think the sin was not the counting, but the way his counting became a basis for policy, and so for value. When we weigh our forces before going to war, the question shifts from "Is this a war worth fighting?" to "Can I win?" Both of those are important questions, but God save us from ever making the latter so important that we think of the former as a question that doesn't count. That kind of thinking turns people into instruments of war rather than free individuals; people become pawns, tools of policy, and they become as expendable as they are enumerable. When we dare to quantify our gains and losses in terms of numbers of human lives expended, we have already lost something important that may be very hard to regain.

And God save us, likewise, from thinking of our lives as things to be measured, and measured against others' lives. God save us from thinking of meaningful work as something to be done against a time clock, from thinking of wealth as something to be measured in numbers rather than in a richness of life. And God save us teachers and citizens from thinking that the worth of a woman or a man can easily be measured by the grades they have earned, or that the predictions we may make on the basis of those grades should have the power of prophecy.

Because "Liberal" in "Liberal Arts" Means "Free"

Martha Nussbaum, Not For Profit: Why Democracy Needs The Humanities. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010) p. 21.

A Republic Without Education

Charles Sumner, Massachusetts Senator, in “Reconstruction Again: The Ballot and Public Schools Open to All,” speeches in the Senate, on the Supplementary Reconstruction Bill, March 15 and 16, 1867. TheWorks of Charles Sumner, Vol XI, (Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1875) p. 156

An Ounce Of Prevention

I've lost track of how many times I've heard someone say recently that the point of the Second Amendment is, first of all, to safeguard the other rights enumerated in the Constitution, and second, that a well-regulated militia is necessary in case we ever need to overthrow a government that has turned into a tyranny.

I have a little (though not much) sympathy with the second of those positions, but the first is, I think, simply wrong. Here's why: the First Amendment is itself an extremely powerful tool, and it is fitting that it should precede the Second, because an attempt to solve problems by reasonable words should always precede the attempt to solve our problems by force. In other words, if we exercise our First Amendment rights responsibly, we will never need to invoke the Second to overthrow our government. One of the beautiful things about our Constitution is the way it provides means for us to address unjust power grabs by our government officials without starting an insurrection.

But the bigger problem is one of what fills our hearts and minds: Focusing our attention on preparing to overthrow a future tyranny is like a physician preparing to euthanize a patient who might someday become ill. Yes, it is possible to "cure" any illness by killing the patient, but it's not good medicine. We need more than just preparedness to kill a disease; we need to promote good health as well.

If you're concerned about the nation becoming a tyranny, buying more guns is a poor response. Here are some far better responses:

* Thomas Cleary tells this story in the translator's introduction to his edition of Sun Tzu's The Art Of War (Shambhala: Boston and London, 1988) p. 1.

Evolution and Education

Is God capable of creating through natural processes?There are only two answers to this question. If you say no, you make God too small to be worth worshiping. If you say yes, then you see that there's no prima facie reason why belief in God and belief in evolution need to be opposed to one another.

Of course, this doesn't clear up all the obstacles to reconciling religious belief and confidence in science, but it's a start.

If you're a teacher of students who also grapple with this, and you don't understand them, this might help. Some of them will certainly be unreasonable. For them, sometimes all you can do is be an example of reasonable beliefs and hope it sinks in someday. But many of them are concerned about a few big questions, like these:

Google Wave and My Course in Greece

Each year I teach a course in Greece, and I require my students to make presentations at a variety of archaeological and cultural sites.

This year I am playing around with Google Wave's map feature and wondering if I can use Wave to help prepare my students to make the most of our limited time in Greece.

Do you have suggestions for how I can use this for my course? Are you also new to Wave and interested in Greece? If so, send me a wave at dr.dlohara@googlewave.com and I'll include you in my "sandbox" where I'm playing around with the possibilities.

(Photo credit: Dr. Jeffrey A. Johnson, Providence College)

Every Time You Open A Prison...

…you close a school." - Victor Hugo.

“Why is it considered morally offensive and economically unwise in this country to give a poor person a few dollars more than $13.22 per day, but ethically appropriate and fiscally sensible to incarcerate a poor person at an average cost of $55.18 per day?” - Jens Soering, An Expensive Way to Make Bad People Worse. (Click here for Wikipedia’s article on Jens Soering.)

Hugo is obviously being provocative; education does not guarantee moral goodness. And Soering is similarly making a comparison that leaves out the important fact that criminals freely choose to commit their crimes. Nevertheless, good education does create opportunity, whereas inequality in education seems like an invitation to the poor to continue to consider themselves to be perpetually unequal to the wealthy and so perpetually unable to advance economically without crime.

Selah.

Scholia, Essays, and Education

In an earlier post I spoke of the pleasures of finding marginalia in others' books, and of writing one's own marginalia. The word "marginalia" means, of course, "things [written] in the margin." In a way, the aim of education is to prepare us to write our own marginalia.

We set aside places for education, and these we call "schools," from the Greek word scholé, meaning "leisure." Most students don't think of schools as places of leisure, but it is only a person with leisure from menial daily work who has the leisure for school.

That word scholé is also related to the word scholion (Greek) or scholium (Latin). Those words mean "a comment." The act of reading is not complete with seeing the words on the page; we have read a text when we have observed it, worked to understand it, and then contemplated its meaning for our own lives. Looking at words without reflecting on them and then calling it reading is like looking at a menu without eating a meal and calling it "going to a restaurant." Technically true, but not at all nourishing.

Those with leisure to read books also have the leisure to reflect on books and on what they mean for us. When that reflection takes the form of scholia (the plural of scholion and scholium) - that is, when we write comments on texts, the writing is an attempt to complete the act of reading. So when we teachers assign essays we are (ideally) not assigning writing so much as reading. The aim is not a polished essay; the polished essay is merely the sign of something else. The aim is reflection on texts. The word "essay" comes from a French word meaning "attempt, try"; each essay is an attempt to become a little better at observing texts, at understanding what they mean, and at articulating what they mean for us.