Emerson

∞

Charles Peirce on Transcendentalism, and the Common Good

From one of Charles S. Peirce's college writings, dated 1859. At the time he was a student at Harvard College.

It's a short paragraph, but it offers considerable insight into the development of Peirce's thought, and it is full of suggestion for our own time.

His claim that a scholar must devote herself to one area only must be taken in the context of Peirce's own studies. Peirce was himself a polymath who wrote on logic, metaphysics, physics, geometry, ancient philology, semiotics, mathematics, and chemistry, among other disciplines.

What he says about learning here is relevant for the ancient tradition of publishing the results of inquiry, and for the contemporary practice of patenting all discoveries. Nature is not a gift from God to the individual researcher. Peirce's invocation of God here calls to mind what he says elsewhere about both God and research. (For more on how Peirce regarded the relationship between God and science, see my chapter in Torkild Thellefsen's collection of essays on Peirce, Peirce in His Own Words.) The idea of God provides an ideal for the researcher, a reason to expect natural research to be productive of knowledge and a reason to believe in the possible unity of knowledge.

(This helps us to understand Peirce's peculiar interest in religion, by the way: he thought religion both indispensable and unavoidable, claiming that even most atheists believe in God, though most of them are unaware of their own belief, because they have explicitly rejected a particular kind of theism while maintaining a steadfast belief in some of the consequences of theism. At the same time, Peirce was opposed to all infallible claims, to the exclusionary nature of creeds, and to what he considered to be the illogic of seminary-training.)

Peirce grew up, as he puts it, "in the neighborhood of Cambridge," i.e. near the home of American Transcendentalism. He says of his family that "one of my earliest recollections is hearing Emerson [giving] his address on 'Nature'.... So we were within hearing of the Transcendentalists, though not among them. I remember when I was a child going upon an hour's railway journey with Margaret Fuller, who had with her a book called the Imp [3] in the Bottle." (MS 1606) His critiques of Transcendentalism have to be read in this context: he was raised among them, with Emerson in his childhood living room and with Emerson's writings being discussed in his school.

Emerson's insight is that nature does speak to those who have ears to hear. His error is in mistaking the relationship of one person to another. Emerson's genius is in perceiving the Over-soul, and his error is in then presupposing the radical individuality of the genius. Peirce does not doubt that there are geniuses. As a chemist, Peirce knew the importance of research and he knew the real possibility of achieving previously unknown insight. Peirce believed, however, that the insight of the genius, or of any serious researcher for that matter, belongs to the whole community of inquiry.

Peirce, who made his living on research, believed that the researcher deserved to earn her living from her work, and he was sometimes frustrated by the chemical companies who took his ideas and patented them, then refused to pay him for them. His ideal - one that is admittedly very difficult to realize - was that all research would be made freely available to the whole community of inquiry. So while the researcher is worth her wages, no one deserves the privilege of hoarding knowledge for private gain. We are all in this together.

******

[1] I'm not sure which Everett Peirce alludes to, but possibly to Edward Everett, who was Emerson's teacher; or Alexander H. Everett, with whom Emerson corresponded.

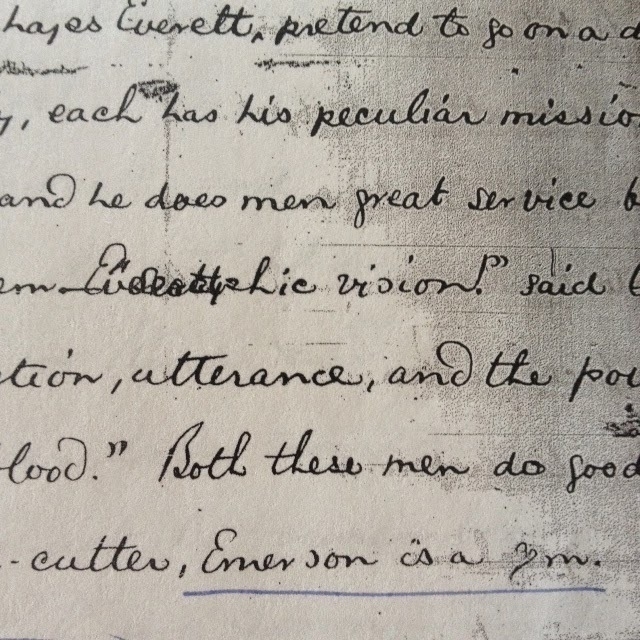

[2] The word on Peirce's manuscript is difficult to read. I have transcribed this from a photocopy of one of Peirce's original handwritten pages. The word might be "ecstatic" but I don't think it is. See the image above. [Update: Chris Paone wrote to me with the suggestion that the obscured word might be "seraphic." This is a better guess than any I've come up with so far, so until someone has a better idea, I'll take Chris to be right.]

[3] This word is also unclear, and might read "Ink." If you're curious about this, or if you've got some insight about this, write to me in the comments below; I've spent some time trying to figure out what book Fuller had with her, so far with only a small amount of success.

With each of these footnotes, I welcome your feedback and corrections in the footnotes below. Peirce wrote that the work of the researcher is never a solitary affair, but always the work of a community of inquiry, after all.

"The devotion to fair learning is not of this rabid kind, but it is more selfish. Antiquity has not accumulated its treasures for me; God has not made nature for me: if I wish to belong to the community of wise men, my time is not my own; my mind is not my own; in this age division of labor is indispensable; one man must study one thing; develope one part of his intellect and, if necessary, let the rest go, for the good of humanity. Emerson, and perhaps Everett [1], pretend to go on a different principle; but really, each has his peculiar mission. Emerson is the man-child and he does men great service by just opening himself to them. "Seraphic [2] vision!" said Carlyle. Everett possesses "action, utterance, and the power of speech to stir men's blood." Both these men do good esthetically. Everett is a gem-cutter, Emerson is a gem." (MS 1633)

|

| A section of MS 1633, dated 1859 |

It's a short paragraph, but it offers considerable insight into the development of Peirce's thought, and it is full of suggestion for our own time.

His claim that a scholar must devote herself to one area only must be taken in the context of Peirce's own studies. Peirce was himself a polymath who wrote on logic, metaphysics, physics, geometry, ancient philology, semiotics, mathematics, and chemistry, among other disciplines.

What he says about learning here is relevant for the ancient tradition of publishing the results of inquiry, and for the contemporary practice of patenting all discoveries. Nature is not a gift from God to the individual researcher. Peirce's invocation of God here calls to mind what he says elsewhere about both God and research. (For more on how Peirce regarded the relationship between God and science, see my chapter in Torkild Thellefsen's collection of essays on Peirce, Peirce in His Own Words.) The idea of God provides an ideal for the researcher, a reason to expect natural research to be productive of knowledge and a reason to believe in the possible unity of knowledge.

(This helps us to understand Peirce's peculiar interest in religion, by the way: he thought religion both indispensable and unavoidable, claiming that even most atheists believe in God, though most of them are unaware of their own belief, because they have explicitly rejected a particular kind of theism while maintaining a steadfast belief in some of the consequences of theism. At the same time, Peirce was opposed to all infallible claims, to the exclusionary nature of creeds, and to what he considered to be the illogic of seminary-training.)

Peirce grew up, as he puts it, "in the neighborhood of Cambridge," i.e. near the home of American Transcendentalism. He says of his family that "one of my earliest recollections is hearing Emerson [giving] his address on 'Nature'.... So we were within hearing of the Transcendentalists, though not among them. I remember when I was a child going upon an hour's railway journey with Margaret Fuller, who had with her a book called the Imp [3] in the Bottle." (MS 1606) His critiques of Transcendentalism have to be read in this context: he was raised among them, with Emerson in his childhood living room and with Emerson's writings being discussed in his school.

Emerson's insight is that nature does speak to those who have ears to hear. His error is in mistaking the relationship of one person to another. Emerson's genius is in perceiving the Over-soul, and his error is in then presupposing the radical individuality of the genius. Peirce does not doubt that there are geniuses. As a chemist, Peirce knew the importance of research and he knew the real possibility of achieving previously unknown insight. Peirce believed, however, that the insight of the genius, or of any serious researcher for that matter, belongs to the whole community of inquiry.

Peirce, who made his living on research, believed that the researcher deserved to earn her living from her work, and he was sometimes frustrated by the chemical companies who took his ideas and patented them, then refused to pay him for them. His ideal - one that is admittedly very difficult to realize - was that all research would be made freely available to the whole community of inquiry. So while the researcher is worth her wages, no one deserves the privilege of hoarding knowledge for private gain. We are all in this together.

******

[1] I'm not sure which Everett Peirce alludes to, but possibly to Edward Everett, who was Emerson's teacher; or Alexander H. Everett, with whom Emerson corresponded.

[2] The word on Peirce's manuscript is difficult to read. I have transcribed this from a photocopy of one of Peirce's original handwritten pages. The word might be "ecstatic" but I don't think it is. See the image above. [Update: Chris Paone wrote to me with the suggestion that the obscured word might be "seraphic." This is a better guess than any I've come up with so far, so until someone has a better idea, I'll take Chris to be right.]

[3] This word is also unclear, and might read "Ink." If you're curious about this, or if you've got some insight about this, write to me in the comments below; I've spent some time trying to figure out what book Fuller had with her, so far with only a small amount of success.

With each of these footnotes, I welcome your feedback and corrections in the footnotes below. Peirce wrote that the work of the researcher is never a solitary affair, but always the work of a community of inquiry, after all.

∞

I spent my twentieth year of life in Madrid, Spain, studying Spanish philology. Studying abroad is like laboratory work in a science class: the experience often teaches much more than lectures or readings could ever do. Many of the lessons are unanticipated, and depend on the interaction of student and environment.

One day in February, for no particular reason, I wanted to eat strawberries. A few blocks from my flat there was a market, so I walked there and searched for fruit stands. Finding one but seeing that they had no strawberries, I asked the proprietor, "Do you know where I can find strawberries?"

"Of course," he replied. "Right here."

"But you don't have any," I observed.

"Of course I don't," he said.

I was confused. "But you said I could find strawberries right here."

"You can," he replied. "But not until June."

This took a little while to sink in. I was accustomed to going to a supermarket at home in New York and buying any fruit I wanted at any time of year. Now I was being told what should have been perfectly clear: fruit is seasonal.

At first I was disappointed, but it took only a few minutes before I realized that this wasn't such a bad thing. It meant that the strawberries, when they arrived, would taste that much sweeter. The disappointment of having to wait would be repaid by the delight when they did arrive.

The experience didn't reform me, of course. I love eating my favorite foods year-round, despite not having harvested them and usually without knowing where they came from.

But it did make me appreciate some of the rhythms of life around me. The first part of Aldo Leopold's A Sand County Almanac, and most of Thoreau's Walden - two of my favorite books - follow the cycle of the seasons in the northern part of the United States. Their understanding of nature is one that allows nature to undergo its habitual changes. They might even say that what they know about nature arises from attention to just those changes. Phenology, the attention to when and how things appear and disappear throughout seasons, is one of the most important parts of learning to see the world. If I may speak an Emersonian word, phenology attunes us to the music nature wants us to hear. To speak less mystically, it accustoms us to natural patterns, and much of what the naturalist wants is to learn those patterns so well that we can then see when nature departs from them.

What are the calendars in your life? Technology has made many of them seem unnecessary, but I suspect that they give us much more than we know, just as my experience in Spain gave me unlooked-for lessons. We should be careful not to insist that others delight in the absences or disciplines we delight in; what may be a delightful, self-imposed fast to us may be devastating to someone who is genuinely hungry. When we choose them for ourselves, school calendars, planning one's garden, the liturgical calendars and holidays of the world's religions - each of them can offer us rhythms of both discipline and delight as we make ourselves wait for the strawberries to ripen, the hummingbirds to return, the exams to end, the candles to be lit.

Searching For Winter Strawberries

|

| A late October strawberry in my garden |

One day in February, for no particular reason, I wanted to eat strawberries. A few blocks from my flat there was a market, so I walked there and searched for fruit stands. Finding one but seeing that they had no strawberries, I asked the proprietor, "Do you know where I can find strawberries?"

"Of course," he replied. "Right here."

"But you don't have any," I observed.

"Of course I don't," he said.

I was confused. "But you said I could find strawberries right here."

"You can," he replied. "But not until June."

This took a little while to sink in. I was accustomed to going to a supermarket at home in New York and buying any fruit I wanted at any time of year. Now I was being told what should have been perfectly clear: fruit is seasonal.

At first I was disappointed, but it took only a few minutes before I realized that this wasn't such a bad thing. It meant that the strawberries, when they arrived, would taste that much sweeter. The disappointment of having to wait would be repaid by the delight when they did arrive.

The experience didn't reform me, of course. I love eating my favorite foods year-round, despite not having harvested them and usually without knowing where they came from.

But it did make me appreciate some of the rhythms of life around me. The first part of Aldo Leopold's A Sand County Almanac, and most of Thoreau's Walden - two of my favorite books - follow the cycle of the seasons in the northern part of the United States. Their understanding of nature is one that allows nature to undergo its habitual changes. They might even say that what they know about nature arises from attention to just those changes. Phenology, the attention to when and how things appear and disappear throughout seasons, is one of the most important parts of learning to see the world. If I may speak an Emersonian word, phenology attunes us to the music nature wants us to hear. To speak less mystically, it accustoms us to natural patterns, and much of what the naturalist wants is to learn those patterns so well that we can then see when nature departs from them.

What are the calendars in your life? Technology has made many of them seem unnecessary, but I suspect that they give us much more than we know, just as my experience in Spain gave me unlooked-for lessons. We should be careful not to insist that others delight in the absences or disciplines we delight in; what may be a delightful, self-imposed fast to us may be devastating to someone who is genuinely hungry. When we choose them for ourselves, school calendars, planning one's garden, the liturgical calendars and holidays of the world's religions - each of them can offer us rhythms of both discipline and delight as we make ourselves wait for the strawberries to ripen, the hummingbirds to return, the exams to end, the candles to be lit.

∞

The Importance of Struggling to Understand

In his speech when he was awarded the Emerson-Thoreau Medal, Robert Frost made this poignant aside about his years of struggling with one of Emerson's poems:

"I don't like obscurity and obfuscation, but I do like dark sayings I must leave the clearing of to time. And I don't want to be robbed of the pleasure of fathoming depths for myself."

"I don't like obscurity and obfuscation, but I do like dark sayings I must leave the clearing of to time. And I don't want to be robbed of the pleasure of fathoming depths for myself."

Robert Frost, "On Emerson." In Selected Prose of Robert Frost. Hyde Cox and Edward Connery Lathem, eds.(New York: Collier, 1968) p.114. (Originally delivered as an address to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences on the occasion of Frost's being awarded the Emerson-Thoreau Medal. Later published in Daedalus, Fall 1959.)I like Frost's use of "clearing" which still echoes the older meaning of "clear," that is "brighten." Frost's point is also excellent: simply explaining poetry, or great texts, to students is not enough. It is often helpful to guide them and to show them hermeneutical tools, or to speak with them about how we ourselves have grappled with texts, but we should be careful about the temptation to explain, since explanations can rob students of the pleasure of discovery. Poetry has immense value for us, and one -- just one -- of its benefits is the way that it can become the means by which we learn to solve problems that we have never encountered before.

∞

No Flash!

My job as a college professor brings me to a lot of museums and archives, and this summer has been especially full of visits to museums, historical sites, and archives in Greece, Norway, the U.K., and the U.S.

As a kid I found most museums boring, but now I really appreciate and enjoy them. I've spent many days of my life in the British Museum and in several museums in Athens, and each time I'm there I feel that time is rewarded with fresh discoveries and with reacquaintance with familiar objects.

Some museums have a reasonable policy of not permitting flash photography, since the bright light of camera flashes can degrade the colors of paint and dyes. Others must insist on no photography when the objects on display are on loan from owners who will not permit reproductions of their images.

But in general, I object when museums and archives prohibit photography, especially when the aim is to force more visitors to come to the physical site. Most people the world over will never be able to visit the world's great museums. And many scholars could benefit from digital images of archival materials. During a recent visit to an archive that hosts many of Henry David Thoreau's papers, I was disappointed to learn that I would not be permitted to take photos of some of the papers I wanted to read later. This forces scholars to spend more time in the archive, which means spending more money - simply prohibitive for many of us. So I type, or scribble, as quickly as I can to transcribe texts in some archives, and hope that I can somehow find what I need in the time I have.

The Ballpoint As A Tool For Seeing

But what if what you want to remember is not a text but an image? Scott Parsons, a gifted artist and a friend of mine, has taught me that one need not be very talented with a pen to begin to capture images. As Dr. Cornelius said in one of Lewis's stories, "A scholar is never without [pen and paper]," and I've tried to make that my rule, too, carrying pen and paper with me everywhere. Scott tells me that a cheap ballpoint pen is, after all, one of the best tools for seeing.

It turns out, he's right: the pen is often mightier than the camera. I think this is because the camera captures all available light, while the pen only captures what my eye and hand tell it to. The chief obstacle to overcome is the disconnect between what my eye sees and what my hand draws. Scott has pointed out to me that this is not the fault of my hand so much as a problem of mistaking what I think I see for what I actually see. In other words, it is a problem of misdirected attention, when I pay attention to what I think is there rather than to what the light is actually doing.

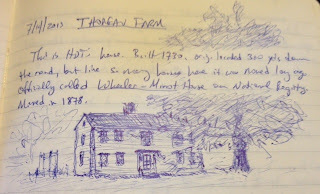

So far, no one in any museum has objected to my drawing what I see. In most cases, when I draw pictures, people seem honored that I should take the time. I drew this picture of the Thoreau homestead in Concord this summer, and a curator there happened to see it as I journaled. She seemed pleased that I took the time to try to draw it. I find that taking the time to draw helps me to notice details I'd have otherwise missed. You can see I'm not a great artist, little improved from my youth. But I'm not ashamed, because even if it's not a brilliant representation, it doesn't need to be; it is a record, in blue lines, of ten minutes of attention. The image is not a photograph; it is a symbol of memory, like a call number for a book in a library that helps me to recall quickly the time I spent sitting on the grass in Concord considering the place where Henry David grew up.

Memories Of Delight

I've also begun drawing inside people's homes when I'm a guest there - always with permission, of course. This summer several kind Norwegian friends took me in for a week, giving me space to write while overlooking a fjord, and cooking me delicious Norwegian food. In the evening we built fires in the hearth and talked quietly or played cards. These are fond memories with friends, but they're also memories of delight in seeing new shapes of things. Norwegians build fires and eat waffles as we Americans do, but the fireplaces and the waffle irons are different from the ones I know from my home. The waffles I saw were all shaped like heart-flowers, giving visual delight in addition to the delightful taste (though I'm not yet sold on brown cheese as a topping.) The fireplaces I saw were all open on not just one side, but two. They looked different, but it was only when I began to draw them that I noticed what I was seeing. This is a small thing, perhaps, but it is a reminder that what I take to be the natural shape of things often has as much to do with the traditions I grew up with as with nature. As an aside, when I take the time to draw pictures, it often seems to be taken as a sign of respect, which is just how I intend it: this place you live in, this object in your home, is so wonderful to me that I wish to give it my attention and make it a permanent resident in my journal, the log-book of my heart. May I? Thank you, and thank you for the hospitality that allowed me to witness this.

Pics Or It Didn't Happen

Sometimes I choose not to take photos simply because the camera is itself a sign. When we hold it in front of our face, it becomes not just a lens through which we see, but a symbol of distance: this moment, this image, matters because it will matter somewhere else, somewhen else. There's nothing wrong with wanting to preserve the moment, but when the apparatus becomes the medium through which we perceive everything - when we feel we must record a photonic image of everything to make the moment real, reality itself somehow becomes less to us.

Icons As Luminous Doorways

This summer I had the privilege of visiting the Monastery of Hosios (Saint) Loukas near Delphi in Greece. I'm not Orthodox, but I have real appreciation for what I learn from the Orthodox traditions. An Orthodox priest in my town has told me that icons are not objects of worship, but means of worship, images that help us to pray, just as windows help us to see. The pray-er who regards the icon isn't supposed to see the icon, but, as with windows, to see through the icon. In some sense the artistic image is intended to vanish when it is doing what it was intended to do. This language has been a little bit mysterious to me at times, but at the monastery this summer I had an illustrative experience: I stood in a doorway with bright sunlight shining behind me. Ahead, I could see through another doorway into the narthex of a chapel, and then through another doorway, to the altar at the far end. Beside every Orthodox altar there is an icon of Christ. This one was covered with glass, as icons often are. The glass reflected back to me the image of the doorway behind me, as though in the center of the image of Christ there were a luminous doorway. I tried to take a photo of this, but the contrasts were too great. So I took out my paper and pen and sketched what I saw. It's not a superb image, but it turned out far better than my photographic attempts did. And, as in other cases, I found myself feeling considerably more present and more respectful of the place.

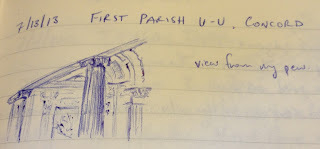

The View From The Pew

This was the case with several other holy sites I visited this summer as well. I had the privilege of hearing Robert Richardson lecture on Emerson in the Unitarian church in Concord, MA this summer, and then to visit the "African Meeting House" in Boston, a site of worship and of community activism for African Americans in the 19th century. It somehow didn't feel right to let the camera intrude into these places. The pen, by contrast, felt like an instrument properly reverent. Each stroke of the pen strengthening lines became like a prayer or an act of gratitude and reverence for the places I was in. In each case I sketched a "view from my pew," the view I had while sitting as worshipers have sat there in times past - and present.

No Photos!

But to return to the complaint with which I began this piece, too many places insist that no photography be allowed inside. While participating in a Summer Institute on Transcendentalism sponsored by the National Endowment for the Humanities this summer, I was able to visit some wonderful places, like the Thoreau Homestead, several of the homes of Louisa May Alcott, and Emerson's home. Visiting these places makes me a better teacher: they help me to tell a better story about the texts and ideas that emerged from them. Bronson Alcott, Louisa May's father, may have been odd, but his oddity is fascinating and delightful. He built this outbuilding to house his Concord School of Philosophy, for instance:

Architecture As The Embodiment Of Ideas

And he had some beautiful ideas about education: like the belief that children should be allowed to learn what they love to learn, that they should become bodily and sensorily engaged in their learning, that they should run and play and have recess, that art and literature should be significant in their learning, and so on. I knew these ideas before visiting his Concord home and Fruitlands, but seeing the buildings he built to house his ideas helps me to see how he envisioned those ideas at work.

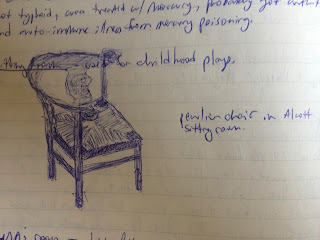

Unfortunately, I can only show you the outside of the buildings at the Alcott house, because there's no photography allowed inside, nor at the Emerson home either. So if you live far away, tant pis. I guess you'll have to just travel and visit it. Or, if you like, I can share the sketches I was able to make in our hurried tour. Yes, let's do that. I loved this chair, which is so oddly shaped. In a time when so many chairs seemed intended to make you sit ramrod straight, this one seems to invite you to slouch in different directions, to be at ease in your own body, to delight in sitting in the company of others:

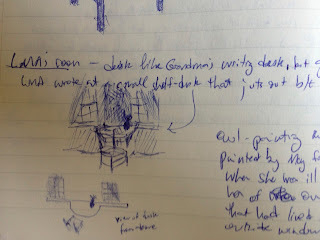

The Alcotts weren't wealthy, but Bronson and his wife managed to provide each of their children with a room of their own, and each of those rooms is suited to the disposition and arts of the child. Louisa May's room has a beautiful little half-moon shelf-desk jutting out between two large windows, perfect for writing stories and books, with excellent light. When I visited, the room was full of tourists, so a photo wouldn't have captured it anyway, and my drawing is very hasty and a little cramped itself, but here's a rough idea of what it looks like while standing beside her bed, plus an attempt to give the bird's-eye view:

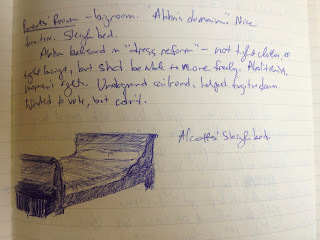

Bronson and his wife Abby had some lovely furniture, and I was especially captivated by their sleigh-bed. Its curved ends and gentle woodwork make the bed seem a place worth being, a place of rest and delight:

What I wish is that the owners and curators of these places would recognize that allowing visitors to take photos can help us to preserve the very places we are visiting, and to teach others about them. I understand the desire to make those places special, just as I understand the fear that if you allow images to be taken maybe fewer visitors will come. But for us teachers, taking pictures can be a way to allow our students to visit a place they might otherwise never go.

Thankfully, no one has yet prohibited my pen and paper. Or yours. I'm not up to Urban Sketchers quality, and may never be, but I'm not ashamed to use my pen as a visual instrument, nor to share with you what I've seen through it. And I hope you'll do the same.

Rebel Without A Camera: Museums, Images, and Memory

|

| My old Brownie. No flash! |

As a kid I found most museums boring, but now I really appreciate and enjoy them. I've spent many days of my life in the British Museum and in several museums in Athens, and each time I'm there I feel that time is rewarded with fresh discoveries and with reacquaintance with familiar objects.

Some museums have a reasonable policy of not permitting flash photography, since the bright light of camera flashes can degrade the colors of paint and dyes. Others must insist on no photography when the objects on display are on loan from owners who will not permit reproductions of their images.

But in general, I object when museums and archives prohibit photography, especially when the aim is to force more visitors to come to the physical site. Most people the world over will never be able to visit the world's great museums. And many scholars could benefit from digital images of archival materials. During a recent visit to an archive that hosts many of Henry David Thoreau's papers, I was disappointed to learn that I would not be permitted to take photos of some of the papers I wanted to read later. This forces scholars to spend more time in the archive, which means spending more money - simply prohibitive for many of us. So I type, or scribble, as quickly as I can to transcribe texts in some archives, and hope that I can somehow find what I need in the time I have.

The Ballpoint As A Tool For Seeing

But what if what you want to remember is not a text but an image? Scott Parsons, a gifted artist and a friend of mine, has taught me that one need not be very talented with a pen to begin to capture images. As Dr. Cornelius said in one of Lewis's stories, "A scholar is never without [pen and paper]," and I've tried to make that my rule, too, carrying pen and paper with me everywhere. Scott tells me that a cheap ballpoint pen is, after all, one of the best tools for seeing.

It turns out, he's right: the pen is often mightier than the camera. I think this is because the camera captures all available light, while the pen only captures what my eye and hand tell it to. The chief obstacle to overcome is the disconnect between what my eye sees and what my hand draws. Scott has pointed out to me that this is not the fault of my hand so much as a problem of mistaking what I think I see for what I actually see. In other words, it is a problem of misdirected attention, when I pay attention to what I think is there rather than to what the light is actually doing.

|

| Thoreau Farm |

|

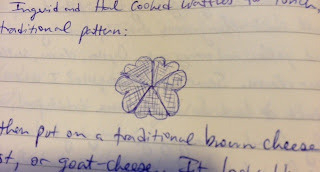

| Norwegian waffle: a bouquet of hearts |

|

| Norwegian fireplace |

I've also begun drawing inside people's homes when I'm a guest there - always with permission, of course. This summer several kind Norwegian friends took me in for a week, giving me space to write while overlooking a fjord, and cooking me delicious Norwegian food. In the evening we built fires in the hearth and talked quietly or played cards. These are fond memories with friends, but they're also memories of delight in seeing new shapes of things. Norwegians build fires and eat waffles as we Americans do, but the fireplaces and the waffle irons are different from the ones I know from my home. The waffles I saw were all shaped like heart-flowers, giving visual delight in addition to the delightful taste (though I'm not yet sold on brown cheese as a topping.) The fireplaces I saw were all open on not just one side, but two. They looked different, but it was only when I began to draw them that I noticed what I was seeing. This is a small thing, perhaps, but it is a reminder that what I take to be the natural shape of things often has as much to do with the traditions I grew up with as with nature. As an aside, when I take the time to draw pictures, it often seems to be taken as a sign of respect, which is just how I intend it: this place you live in, this object in your home, is so wonderful to me that I wish to give it my attention and make it a permanent resident in my journal, the log-book of my heart. May I? Thank you, and thank you for the hospitality that allowed me to witness this.

Pics Or It Didn't Happen

Sometimes I choose not to take photos simply because the camera is itself a sign. When we hold it in front of our face, it becomes not just a lens through which we see, but a symbol of distance: this moment, this image, matters because it will matter somewhere else, somewhen else. There's nothing wrong with wanting to preserve the moment, but when the apparatus becomes the medium through which we perceive everything - when we feel we must record a photonic image of everything to make the moment real, reality itself somehow becomes less to us.

|

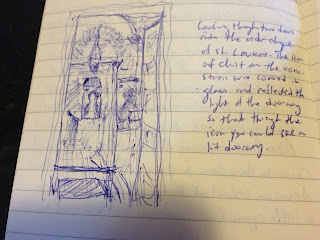

| Ecce: the heart of Christ, a luminous doorway |

This summer I had the privilege of visiting the Monastery of Hosios (Saint) Loukas near Delphi in Greece. I'm not Orthodox, but I have real appreciation for what I learn from the Orthodox traditions. An Orthodox priest in my town has told me that icons are not objects of worship, but means of worship, images that help us to pray, just as windows help us to see. The pray-er who regards the icon isn't supposed to see the icon, but, as with windows, to see through the icon. In some sense the artistic image is intended to vanish when it is doing what it was intended to do. This language has been a little bit mysterious to me at times, but at the monastery this summer I had an illustrative experience: I stood in a doorway with bright sunlight shining behind me. Ahead, I could see through another doorway into the narthex of a chapel, and then through another doorway, to the altar at the far end. Beside every Orthodox altar there is an icon of Christ. This one was covered with glass, as icons often are. The glass reflected back to me the image of the doorway behind me, as though in the center of the image of Christ there were a luminous doorway. I tried to take a photo of this, but the contrasts were too great. So I took out my paper and pen and sketched what I saw. It's not a superb image, but it turned out far better than my photographic attempts did. And, as in other cases, I found myself feeling considerably more present and more respectful of the place.

|

| First Parish, Concord, Mass. |

|

| African Meeting House, Boston, Mass. |

This was the case with several other holy sites I visited this summer as well. I had the privilege of hearing Robert Richardson lecture on Emerson in the Unitarian church in Concord, MA this summer, and then to visit the "African Meeting House" in Boston, a site of worship and of community activism for African Americans in the 19th century. It somehow didn't feel right to let the camera intrude into these places. The pen, by contrast, felt like an instrument properly reverent. Each stroke of the pen strengthening lines became like a prayer or an act of gratitude and reverence for the places I was in. In each case I sketched a "view from my pew," the view I had while sitting as worshipers have sat there in times past - and present.

No Photos!

But to return to the complaint with which I began this piece, too many places insist that no photography be allowed inside. While participating in a Summer Institute on Transcendentalism sponsored by the National Endowment for the Humanities this summer, I was able to visit some wonderful places, like the Thoreau Homestead, several of the homes of Louisa May Alcott, and Emerson's home. Visiting these places makes me a better teacher: they help me to tell a better story about the texts and ideas that emerged from them. Bronson Alcott, Louisa May's father, may have been odd, but his oddity is fascinating and delightful. He built this outbuilding to house his Concord School of Philosophy, for instance:

|

| Alcott's Concord School of Philosophy, Orchard House |

And he had some beautiful ideas about education: like the belief that children should be allowed to learn what they love to learn, that they should become bodily and sensorily engaged in their learning, that they should run and play and have recess, that art and literature should be significant in their learning, and so on. I knew these ideas before visiting his Concord home and Fruitlands, but seeing the buildings he built to house his ideas helps me to see how he envisioned those ideas at work.

|

| Chair in the Orchard House |

|

| Louisa May Alcott's writing desk |

|

| The Alcotts' sleigh-bed |

What I wish is that the owners and curators of these places would recognize that allowing visitors to take photos can help us to preserve the very places we are visiting, and to teach others about them. I understand the desire to make those places special, just as I understand the fear that if you allow images to be taken maybe fewer visitors will come. But for us teachers, taking pictures can be a way to allow our students to visit a place they might otherwise never go.

Thankfully, no one has yet prohibited my pen and paper. Or yours. I'm not up to Urban Sketchers quality, and may never be, but I'm not ashamed to use my pen as a visual instrument, nor to share with you what I've seen through it. And I hope you'll do the same.

∞

Bless You!

What should you say when someone sneezes? I've been pondering this for years. Here are my reflections on that, by way of thinking about foreign-language pedagogy, and about what it means to bless someone:

The Emperor Charles V reportedly said that as many languages as a man knows, that many times over is he a man. I don't know if that's true, but in high school I took courage from it. I was athletic, but lean, with a great build for biking and running, but too slender to be considered dangerously manly. My only formal sports were swimming and ultimate frisbee. I loved skiing and hiking and rock-climbing, but the more I exercised, the leaner I got. There was no chance I'd ever become a star athlete, and I think that realization saved me from trying to become what I was not. Although I didn't know Emerson's writing back then, I nevertheless arrived at an Emersonian conclusion: there are as many kinds of manliness, and courage, as there are men and women to embody them. Emerson puts it like this:

This turns out to be a good way to learn one's own language, too. Not everything can be translated, and when you find something in your native tongue that's hard to say in another language, you've found something that is a unique possession of the speakers of your language. Or when you learn that one word in your language takes many forms in another language, you begin to see how your cultural heritage has come equipped with some blind spots. The same is true of grammar, of inflection, of syntax, and so on.

So learning another language is not simply a matter of replacing one vocabulary with another. Learning a language means learning a culture, a history, a literature.

(This is why language-learning software can help, but it's not enough, and it's no substitute for excellent teachers and for studying abroad.)

In middle school, as I was trying to actualize all my potential and to become as many men as I could be, I spent a lot of time learning basic phrases and grammar in other languages. How do you greet someone in this language? How do you say goodbye? How do you ask for what you want? These tend to be fairly straightforward in the languages I studied.

But some phrases were harder. How do you say "Please"? That word is, after all, a contraction of a whole clause, "If it please you," with a subjunctive verb. It's not like a name for an object or a place, which might be easily translated; it's a way of calling on a whole tradition of regarding the wishes of others as important - or at least, of pretending to honor those wishes. Now, most of the languages I studied had simple ways of saying "please," but along the way I discovered that not all English speakers consider "please" to be correct. Some religious communities, for instance, regard such words as unnecessary; we should be willing to give what we're asked for without demanding that the other regard our wishes as important, they reason.

Another phrase similarly exposed something about cultures: what do you say when someone sneezes? In many languages, the answer is that you say "Your health!" Many English speakers I know use the German Gesundheit without knowing that this is what they are saying, in another language. That's fascinating: we feel the need to say something, even if we don't know what the word means.

When I first met my frosh college roommate, Nick, he sneezed. I said the customary thing: "Bless you!" He looked at me oddly, and didn't say anything. Over the coming weeks, I repeated the phrase each time he sneezed. Finally, he asked me "Why do you keep saying that?" I realized I hadn't any better answer than to say that's what I heard others do. His question got me wondering why we acknowledge sneezes.

After all, we don't say something to accompany other bodily functions, do we? Is there a stock phrase for hiccups, or burps? For a rumbling belly? A cough? A yawn?

Over the years, it started to bother me that others felt the need to comment on my sneezes. When I ask people why they do it, I usually get some lame reply about how it's because long ago people believed that sneezes were a sign of some dangerous spiritual or physical ailment; or that it had to do with fear of the Black Plague; or that it was a response to the fear that sneezes were signs of demonic possession; and in any case, sneezes needed to be countered with blessings.

Okay, fine. I'll let the Middle Ages off the hook next time they bless my sneezing. But why do YOU do it? The answer seems to be cultural habit. It's not a necessity of nature, but something we've made ourselves do until we've forgotten why we do it. It's a thoughtless reflex, and I think this is what annoys me.

Now, after years of being a curmudgeon and a grouch about this, I'm starting to reconsider my objection to these responses to my sternutations. On the one hand, these blessings are thoughtless, and they demand a reply of "thank you" when frankly, I'm still recovering from a sneeze and would rather not say anything. On the other hand, perhaps we shouldn't want fewer blessings in our lives, but more of them, or at least more sincere ones.

As I think back over my life, I've received these blessings often from strangers on a bus or a subway, or in a park in a foreign city. People who do not know me stop their activity to speak a word of blessing into my life, to look me in the eye and put into simple words their wishes for my good health.

Speaking does not make things so, not instantly, anyway. But putting things into words is nevertheless very powerful. I'm not talking magic here; I'm talking about the way our words affect ourselves and others. Naming is powerful. When our inarticulate anger or frustration evolves into naming someone as the one who needs to be punished, the person becomes a criminal, something less than a person. The greater the crime, the lesser the human. Because naming is powerful, cursing is powerful. Which is why I taught my kids that it's not words that are bad, but the uses of words.

And if history teaches us anything at all, it shows us how easy we find it to curse others, to come up with simple, curt, dehumanizing names for entire classes of others. We find it easy not to look others in the eye but to look no further than the skin, or to look through others as though they were not there. We find it easy to curse those who live across borders of towns and nations, those who drive in front of us or behind us, those whose faces we never see and whom we know only through a few words we've read online.

In light of that, I suppose that if you want to bless me--indeed, if you find it hard not to bless me--that should be a welcome thing. Just give me a minute to recover from my sneeze before I thank you. And may you be blessed, too.

The Emperor Charles V reportedly said that as many languages as a man knows, that many times over is he a man. I don't know if that's true, but in high school I took courage from it. I was athletic, but lean, with a great build for biking and running, but too slender to be considered dangerously manly. My only formal sports were swimming and ultimate frisbee. I loved skiing and hiking and rock-climbing, but the more I exercised, the leaner I got. There was no chance I'd ever become a star athlete, and I think that realization saved me from trying to become what I was not. Although I didn't know Emerson's writing back then, I nevertheless arrived at an Emersonian conclusion: there are as many kinds of manliness, and courage, as there are men and women to embody them. Emerson puts it like this:

“It is he only who has labor, and the spirit to labor, because courage sees: he is brave, because he sees the omnipotence of that which inspires him. The speculative man, the scholar, is the right hero. Is there only one courage, and one warfare? I cannot manage sword and rifle; can I not therefore be brave? I thought there were as many courages as men. Is an armed man the only hero? Is a man only the breech of a gun, or the hasp of a bowie-knife? Men of thought fail in fighting down malignity, because they wear other armour than their own.”So I threw myself into doing what I was made to do with joy, and to living a brave life in my own way. Some people find learning a foreign language terrifying; I do not. I'm one of those people blessed with an unusual ability to learn foreign languages quickly and with little effort. When I'm around a new language, I listen to its music and its rhythms and make them my own, and I begin to take apart the language as I hear it, so I can think with it, and watch its parts move. And I ask a lot of questions: How do you say this in your language? What does this mean? When do you say that?– R.W. Emerson, Commencement Address given at Middlebury College on July 22, 1845, in Emerson At Middlebury College, Robert Buckeye, ed. (Middlebury, Vermont: Friends of the Middlebury College Library, 1999), p. 39.

This turns out to be a good way to learn one's own language, too. Not everything can be translated, and when you find something in your native tongue that's hard to say in another language, you've found something that is a unique possession of the speakers of your language. Or when you learn that one word in your language takes many forms in another language, you begin to see how your cultural heritage has come equipped with some blind spots. The same is true of grammar, of inflection, of syntax, and so on.

So learning another language is not simply a matter of replacing one vocabulary with another. Learning a language means learning a culture, a history, a literature.

(This is why language-learning software can help, but it's not enough, and it's no substitute for excellent teachers and for studying abroad.)

In middle school, as I was trying to actualize all my potential and to become as many men as I could be, I spent a lot of time learning basic phrases and grammar in other languages. How do you greet someone in this language? How do you say goodbye? How do you ask for what you want? These tend to be fairly straightforward in the languages I studied.

But some phrases were harder. How do you say "Please"? That word is, after all, a contraction of a whole clause, "If it please you," with a subjunctive verb. It's not like a name for an object or a place, which might be easily translated; it's a way of calling on a whole tradition of regarding the wishes of others as important - or at least, of pretending to honor those wishes. Now, most of the languages I studied had simple ways of saying "please," but along the way I discovered that not all English speakers consider "please" to be correct. Some religious communities, for instance, regard such words as unnecessary; we should be willing to give what we're asked for without demanding that the other regard our wishes as important, they reason.

|

| Modern saints at Westminster Abbey; Their stories are a blessing. |

When I first met my frosh college roommate, Nick, he sneezed. I said the customary thing: "Bless you!" He looked at me oddly, and didn't say anything. Over the coming weeks, I repeated the phrase each time he sneezed. Finally, he asked me "Why do you keep saying that?" I realized I hadn't any better answer than to say that's what I heard others do. His question got me wondering why we acknowledge sneezes.

After all, we don't say something to accompany other bodily functions, do we? Is there a stock phrase for hiccups, or burps? For a rumbling belly? A cough? A yawn?

Over the years, it started to bother me that others felt the need to comment on my sneezes. When I ask people why they do it, I usually get some lame reply about how it's because long ago people believed that sneezes were a sign of some dangerous spiritual or physical ailment; or that it had to do with fear of the Black Plague; or that it was a response to the fear that sneezes were signs of demonic possession; and in any case, sneezes needed to be countered with blessings.

Okay, fine. I'll let the Middle Ages off the hook next time they bless my sneezing. But why do YOU do it? The answer seems to be cultural habit. It's not a necessity of nature, but something we've made ourselves do until we've forgotten why we do it. It's a thoughtless reflex, and I think this is what annoys me.

Now, after years of being a curmudgeon and a grouch about this, I'm starting to reconsider my objection to these responses to my sternutations. On the one hand, these blessings are thoughtless, and they demand a reply of "thank you" when frankly, I'm still recovering from a sneeze and would rather not say anything. On the other hand, perhaps we shouldn't want fewer blessings in our lives, but more of them, or at least more sincere ones.

As I think back over my life, I've received these blessings often from strangers on a bus or a subway, or in a park in a foreign city. People who do not know me stop their activity to speak a word of blessing into my life, to look me in the eye and put into simple words their wishes for my good health.

Speaking does not make things so, not instantly, anyway. But putting things into words is nevertheless very powerful. I'm not talking magic here; I'm talking about the way our words affect ourselves and others. Naming is powerful. When our inarticulate anger or frustration evolves into naming someone as the one who needs to be punished, the person becomes a criminal, something less than a person. The greater the crime, the lesser the human. Because naming is powerful, cursing is powerful. Which is why I taught my kids that it's not words that are bad, but the uses of words.

And if history teaches us anything at all, it shows us how easy we find it to curse others, to come up with simple, curt, dehumanizing names for entire classes of others. We find it easy not to look others in the eye but to look no further than the skin, or to look through others as though they were not there. We find it easy to curse those who live across borders of towns and nations, those who drive in front of us or behind us, those whose faces we never see and whom we know only through a few words we've read online.

In light of that, I suppose that if you want to bless me--indeed, if you find it hard not to bless me--that should be a welcome thing. Just give me a minute to recover from my sneeze before I thank you. And may you be blessed, too.

∞

Three Words About Writing: Plato, Emerson, Bugbee

Last weekend I was at a small writing conference in Vermont, where I was asked to give a meditation on writing with a love of wisdom. Although I'm a philosophy professor, I'm not sure I have a bead on loving wisdom yet.

(To paraphrase Thoreau, there are nowadays plenty of philosophy professors, but not so many lovers of wisdom.)

Instead, I offered a reflection on three ideas that matter for me as I write. Here are three that I keep coming back to:

First, a word from Plato: "Follow the argument wherever it leads." And try to find good interlocutors. If you surround yourself with people who say "yes" to everything you say, your writing and your thinking will both atrophy. If the trail leads uphill, it's no good to stay on the level path. Plato seems to have used writing as a way of sketching out how one might begin to solve problems. He didn't give answers so much as good questions. His dialogues survive because they are such good invitations for us to try to work out the solutions ourselves.

Second, Emerson: Your journals are your savings accounts. Your life is the way you earn deposits. "If it were only for a vocabulary the scholar would be covetous of action," he wrote. "Life is our dictionary." Without action, there is no experience; and without experience, the writer's vocabulary becomes continually narrower. Emerson wrote in fragments - very short essays, or sentences - in his journals, and when he sat down to write his essays and lectures, he found those fragments to be a rich vein of inspiration and even of finished work.

Finally, Bugbee: "Get it down." Write forward; don't edit too much. Keep writing, and as much as possible, write the way it comes. Attend to experience as it is given, without trying too hard to color it or shape it. Practice seeing, and seeing honestly, and write what you see.

This isn't by any means a whole course in writing, but it is a place to start. And often, that's what writers need: to start.

Then keep writing.

(To paraphrase Thoreau, there are nowadays plenty of philosophy professors, but not so many lovers of wisdom.)

Instead, I offered a reflection on three ideas that matter for me as I write. Here are three that I keep coming back to:

First, a word from Plato: "Follow the argument wherever it leads." And try to find good interlocutors. If you surround yourself with people who say "yes" to everything you say, your writing and your thinking will both atrophy. If the trail leads uphill, it's no good to stay on the level path. Plato seems to have used writing as a way of sketching out how one might begin to solve problems. He didn't give answers so much as good questions. His dialogues survive because they are such good invitations for us to try to work out the solutions ourselves.

Second, Emerson: Your journals are your savings accounts. Your life is the way you earn deposits. "If it were only for a vocabulary the scholar would be covetous of action," he wrote. "Life is our dictionary." Without action, there is no experience; and without experience, the writer's vocabulary becomes continually narrower. Emerson wrote in fragments - very short essays, or sentences - in his journals, and when he sat down to write his essays and lectures, he found those fragments to be a rich vein of inspiration and even of finished work.

Finally, Bugbee: "Get it down." Write forward; don't edit too much. Keep writing, and as much as possible, write the way it comes. Attend to experience as it is given, without trying too hard to color it or shape it. Practice seeing, and seeing honestly, and write what you see.

This isn't by any means a whole course in writing, but it is a place to start. And often, that's what writers need: to start.

Then keep writing.

∞

"Life Is Our Dictionary"

"Authors we have in numbers, who have written out their vein, and who, moved by a commendable prudence, set sail for Greece or Palestine, follow the trapper into the prairie, or ramble round Algiers to replenish their merchantable stock. If it were only for a vocabulary the scholar would be covetous of action. Life is our dictionary."

R.W. Emerson, "The American Scholar"

∞

Newspapers in 1854

"[The reading and thinking] class has immensely increased. Owing to the

silent revolution which the newspaper has wrought, this class has come

in this country to take in all classes. Look into the morning

trains...with them, enters the car the humble priest of politics,

finance, philosophy, and religion in the shape of the newsboy....Two

pence a head his bread of knowledge costs, and instantly the entire

rectangular assembly, fresh from their breakfast, are bending as one man

to their second breakfast."

R.W. Emerson, 1854.

∞

Is It Time For A New Transcendentalism?

For the last few weeks I have found

myself returning to this question: Is it

time for a new Transcendentalism?

I normally try to write simple blog posts, but this one might get a little technical. I'll try to minimize the jargon (and so, no doubt, will do some injustice to the technical stuff) but feel free to skip the following section if you like.

The Seeds Of Transcendentalism

When we teach Transcendentalism, we emphasize a few key texts by figures like Emerson, Thoreau, Fuller, Carlyle, Coleridge, Hedge, and others of their acquaintance. Attention to nature, and terms like "self-reliance" and "civil disobedience" shape our understanding of the movement, though they are more like the fruit of the movement than its seeds.

One of the most important seeds of Transcendentalism is the refusal to let one's self be owned, defined, or constrained by others. Today, "self-reliance" sounds like a description of someone who owns a generator in case the power goes out, or who learns engine repair so she doesn't need to depend on a mechanic. But closer to the heart of Transcendentalism is suspicion of others' descriptions of the self and the world.

Inspired in part by Kant's phenomenology and in part by German and English Romanticism, Emerson charted a course between the stifling atmosphere of inherited religion and the determinism of mechanistic philosophies. Unable to find a reliable source of knowledge in the experienced world (our perceptions are always a little off, and maybe they're completely mistaken, as when we hallucinate) Kant located another source of knowledge in our innate ability to know the world at all. Kant argued that we have innate structures of knowledge, intuitive forms that transcend all experience and so are not subject to the doubt directed at experience. Emerson Platonized Kant's epistemology, taking Kant to mean that our inward reflections not only form the world, but give us direct access to the meaning of the world. The individual knower knows some things without being taught them by anyone else.

To put that in other terms, Emerson's Transcendentalism emphasized an "original relation to the universe," in which we trust our intuitions and exercise distrust towards beliefs that have come from outside us. This calls for "prospective," not retrospective, thinking, meaning a willingness to look forward to new possibilities rather than looking backwards to the rules and traditions of our ancestors to acquire rules for our lives.

In even simpler terms, when we let churches and other institutions (scientific, economic, cultural, etc) limit our self-understanding, we also allow them to constrain the scope of our possibilities.

A New Transcendentalism

It may seem we no longer need Transcendentalism because churches are losing their authority and many of us feel free to think what we wish. I am skeptical of this latter claim. Peirce argues that we do not seek the truth; we seek relief from the irritation of doubt. We look for beliefs that are comfortable, and the most comfortable beliefs are the ones that mesh well with the beliefs of others around us. C.S. Lewis, in his preface to Athanasius' De Incarnatione, argues that we should read old books because that is one of the surest ways to have our current beliefs challenged. He adds that simply reading broadly in modern books will not do because people who live in any given age tend to share most of their beliefs. Training in history, and especially in the history of ideas, exposes our beliefs to a broader community that can cast doubt on what we believe.

Another way of saying this is that we agree with ideas that bear the imprimatur of our community. One idea that has growing acceptance is the idea that to be human is to be describable. I admit I am fascinated by this idea, and I delight in learning about the molecules that make our bodies, and the ways they interact.

But I find myself resisting this description of life. Not because it seems wrong, but only because it seems incomplete. It is tempting to turn a good description into a complete one, to be satisfied with a partial description precisely because there is no pressure not to accept it.

Isn't this one of the things we mock in earlier ages, though? I mean their unblinking acceptance of what everyone else around them believed. Are we so free of that same tendency in our own age?

Doubt As A Gardener

Let me add at this point that I find myself thinking about this in my quietest times of reflection, which makes me think it's not coming to me as a polemic against something so much as an apology for something. I don't want to argue against science, because I think science is one of the finest things we've ever come up with. What I want is something that will nevertheless act as a loyal opposition to science, a court jester, perhaps, who will listen patiently to court business about the latest discoveries, but then impudently ask "Yes, but why do you care?" Or say "That's really beautiful, isn't it? Now - tell me about beauty in a way that doesn't leave anything out."

It won't be easy. Transcendentalists and jesters aren't often taken seriously, but their work is perhaps the most serious and important type of work. What I am calling for is like what Cornel West calls prophecy, a missional work of justice, a forward-looking, love-driven endeavor that doesn't want to see anyone taken prisoner by a merely adequate account of what it means to be human. I don't have a full vision of what this means; I'm writing about it here as a first step of externalizing a hunch that it's time to reclaim something of Emerson's vision and to plant the seeds of some doubt.

Doubt is not the enemy of faith and knowledge; it is the gardener who prunes the plant so that it may flourish.

I normally try to write simple blog posts, but this one might get a little technical. I'll try to minimize the jargon (and so, no doubt, will do some injustice to the technical stuff) but feel free to skip the following section if you like.

The Seeds Of Transcendentalism

When we teach Transcendentalism, we emphasize a few key texts by figures like Emerson, Thoreau, Fuller, Carlyle, Coleridge, Hedge, and others of their acquaintance. Attention to nature, and terms like "self-reliance" and "civil disobedience" shape our understanding of the movement, though they are more like the fruit of the movement than its seeds.

One of the most important seeds of Transcendentalism is the refusal to let one's self be owned, defined, or constrained by others. Today, "self-reliance" sounds like a description of someone who owns a generator in case the power goes out, or who learns engine repair so she doesn't need to depend on a mechanic. But closer to the heart of Transcendentalism is suspicion of others' descriptions of the self and the world.

Inspired in part by Kant's phenomenology and in part by German and English Romanticism, Emerson charted a course between the stifling atmosphere of inherited religion and the determinism of mechanistic philosophies. Unable to find a reliable source of knowledge in the experienced world (our perceptions are always a little off, and maybe they're completely mistaken, as when we hallucinate) Kant located another source of knowledge in our innate ability to know the world at all. Kant argued that we have innate structures of knowledge, intuitive forms that transcend all experience and so are not subject to the doubt directed at experience. Emerson Platonized Kant's epistemology, taking Kant to mean that our inward reflections not only form the world, but give us direct access to the meaning of the world. The individual knower knows some things without being taught them by anyone else.

To put that in other terms, Emerson's Transcendentalism emphasized an "original relation to the universe," in which we trust our intuitions and exercise distrust towards beliefs that have come from outside us. This calls for "prospective," not retrospective, thinking, meaning a willingness to look forward to new possibilities rather than looking backwards to the rules and traditions of our ancestors to acquire rules for our lives.

In even simpler terms, when we let churches and other institutions (scientific, economic, cultural, etc) limit our self-understanding, we also allow them to constrain the scope of our possibilities.

A New Transcendentalism

It may seem we no longer need Transcendentalism because churches are losing their authority and many of us feel free to think what we wish. I am skeptical of this latter claim. Peirce argues that we do not seek the truth; we seek relief from the irritation of doubt. We look for beliefs that are comfortable, and the most comfortable beliefs are the ones that mesh well with the beliefs of others around us. C.S. Lewis, in his preface to Athanasius' De Incarnatione, argues that we should read old books because that is one of the surest ways to have our current beliefs challenged. He adds that simply reading broadly in modern books will not do because people who live in any given age tend to share most of their beliefs. Training in history, and especially in the history of ideas, exposes our beliefs to a broader community that can cast doubt on what we believe.

Another way of saying this is that we agree with ideas that bear the imprimatur of our community. One idea that has growing acceptance is the idea that to be human is to be describable. I admit I am fascinated by this idea, and I delight in learning about the molecules that make our bodies, and the ways they interact.

But I find myself resisting this description of life. Not because it seems wrong, but only because it seems incomplete. It is tempting to turn a good description into a complete one, to be satisfied with a partial description precisely because there is no pressure not to accept it.

Isn't this one of the things we mock in earlier ages, though? I mean their unblinking acceptance of what everyone else around them believed. Are we so free of that same tendency in our own age?

Doubt As A Gardener

Let me add at this point that I find myself thinking about this in my quietest times of reflection, which makes me think it's not coming to me as a polemic against something so much as an apology for something. I don't want to argue against science, because I think science is one of the finest things we've ever come up with. What I want is something that will nevertheless act as a loyal opposition to science, a court jester, perhaps, who will listen patiently to court business about the latest discoveries, but then impudently ask "Yes, but why do you care?" Or say "That's really beautiful, isn't it? Now - tell me about beauty in a way that doesn't leave anything out."

It won't be easy. Transcendentalists and jesters aren't often taken seriously, but their work is perhaps the most serious and important type of work. What I am calling for is like what Cornel West calls prophecy, a missional work of justice, a forward-looking, love-driven endeavor that doesn't want to see anyone taken prisoner by a merely adequate account of what it means to be human. I don't have a full vision of what this means; I'm writing about it here as a first step of externalizing a hunch that it's time to reclaim something of Emerson's vision and to plant the seeds of some doubt.

Doubt is not the enemy of faith and knowledge; it is the gardener who prunes the plant so that it may flourish.

∞

Reluctant Prayer

I do not like to pray, but I think prayer is important.

Of course, "prayer" can mean many different things, and I do not mean all of them. But - despite my disliking for the activity of prayer - I practice several kinds of prayer.

Petition and Intercession

I spend most of my prayer time asking for things. This probably sounds foolish on more than one level. Here's the thing: I use the language of asking because it's what comes most naturally. I'm not an expert at this. But this asking is, for me, like stretching my muscles before a run. If I stretch well, I can run further and faster, and I do more good than harm. Stretching prepares me to do more than I could have done otherwise. It expels stiffness and inertia and inaction.

Asking God to do good in the lives of others could be a cop-out, where we dump our problems on the divine and then proceed to ignore them. What I try to practice is a kind of asking where I'm not giving up on being part of the solution. Frankly, I think a lot of the big problems in the world will take more than just me, so I have no shame about asking God to do some of the heavy lifting. But it's also important that I take some time out of my day to practice being less concerned with my own worries and more concerned with others. This is not the run; it is the warmup, the stretching. The stretching does some good all on its own, but it also prepares me to do other good.

One part of this I have a hard time sorting out is whether and how to tell people I am praying for them. Some people are grateful for it, others are bothered by it. I understand both of those reactions. There are times when we feel the weight of grief less heavily when we know others care enough to devote part of their day to the contemplation of our suffering. And there are times when it seems like people tell us about their prayers so that we will think more highly of them. I have yet to figure this all out. I'll just say it now: if you tell me of your sorrows, I will do my best to remember those sorrows in my quiet time, and I will bring them, in silent contemplation, into the presence of my contemplation of the divine.

Make Me A Blessing

My main prayer each day is one I learned from actor Richard Gere. Years ago, after he became a Buddhist, he said in an interview that when he meets someone he says to himself, silently, "Let me be a blessing to this person." This has stayed with me, and it seems like a good prayer. (He might not call it a prayer, which is fine with me.) I begin my day with that prayer, in the abstract, something like this: "Let me be a blessing to everyone I encounter, to everyone affected by my life. Let me be a blessing, and not a curse. Let me not bring shame on anyone, and keep me from doing or saying what is foolish or harmful." This is not unlike the well-known prayer of St Francis, whose story I have loved since Professor Pardon Tillinghast first made me study it in college years ago.

We Become Like What We Worship

What lies behind all this is my hunch - and I admit it's just a hunch - that we come to resemble the things that matter most to us, the things that we treasure and mentally caress in our inmost parts. And I think this happens subtly and slowly, the way habits build up, or the way our bodies slowly change over time, one cell division at a time. The little things add up to the big thing; our small gestures become the great sweep of our lives.

So in prayer I'm trying to take time out of each day to at least expose myself once again to the things I think are most worth imitating: love of neighbor, love of justice, peacemaking, contentment, hospitality, generosity, gentleness, defense of the downtrodden, healing, joy, patience, self-control. So much of the rest of my day I wind up chasing after things that take up an amount of time that is disproportionate to their value.

If prayer does nothing else than force me to remember what I claim is important--even if this means exposing myself to myself as a hypocrite--then it has already done me some good. And I hope this will mean I'm less of a jerk to everyone else, too. When I'm honest with myself (and let's be honest, that's not as often as it should be) this leads me to what churches have long called confession and repentance, the acknowledgement that I'm not all I claim to be, that I'm not yet all I could be, that I have let myself and others down, and that needs to change. Perhaps this comes from my long interest in Socrates: I think it's probably healthy to make it a habit to consider one's own life.

Musement and Contemplation

There is another kind of prayer that I find quite difficult most of the time, but sometimes I fall into it, and when I do, it is always a delight. It happens sometimes when I am walking, or in the shower, or while reading something that utterly disrupts my usual patterns of thinking. It happens sometimes while I lie awake at night. Charles Peirce talks about this as "musement," a kind of disinterested contemplation of all our possible and actual experiences.

Emerson called prayer the consideration of the facts of the universe from the highest possible point of view. I'm not sure I get anything like the highest possible point of view when I pray, but contemplative prayer does feel like an attempt to at least consider what such a point of view would be like.

Perhaps the best part of this Peircean/Emersonian kind of prayer is the opportunity for rest. Oddly, Peirce says that this is not a relaxation of one's mental powers but the vigorous use of one's powers. The difference between this and hard work is that musement doesn't try to accomplish anything. Peirce says that we could call this "Pure Play." Play may be physically tiring but it is mentally and spiritually refreshing, and it often shows us things we would not otherwise have seen. At least, this is my experience in the outdoors - I climb mountains and wade in rivers and snorkel in the ocean in order to experience the moment when what is possible becomes actual, when what I have not yet seen becomes a fact in my existence. The novelty of it makes life delicious.

Why I Pray

This is a good deal of what drives me to pray, anyway: I want to love my neighbor and my world more than I actually do, so I spend time preparing to do so; I want to become more like the best things and the best people I know, so I spend time dwelling on them, in the belief that worship shapes my character; and I know it is good for me to have my patterns of thought disrupted, so I try to allow myself to enter into a playful contemplation of the world and all that it symbolizes. None of this is easy. It is like any other exercise, sometimes rewarding, often difficult, and nearly always a preparation for the unexpected.

Of course, "prayer" can mean many different things, and I do not mean all of them. But - despite my disliking for the activity of prayer - I practice several kinds of prayer.

Petition and Intercession

I spend most of my prayer time asking for things. This probably sounds foolish on more than one level. Here's the thing: I use the language of asking because it's what comes most naturally. I'm not an expert at this. But this asking is, for me, like stretching my muscles before a run. If I stretch well, I can run further and faster, and I do more good than harm. Stretching prepares me to do more than I could have done otherwise. It expels stiffness and inertia and inaction.

Asking God to do good in the lives of others could be a cop-out, where we dump our problems on the divine and then proceed to ignore them. What I try to practice is a kind of asking where I'm not giving up on being part of the solution. Frankly, I think a lot of the big problems in the world will take more than just me, so I have no shame about asking God to do some of the heavy lifting. But it's also important that I take some time out of my day to practice being less concerned with my own worries and more concerned with others. This is not the run; it is the warmup, the stretching. The stretching does some good all on its own, but it also prepares me to do other good.

One part of this I have a hard time sorting out is whether and how to tell people I am praying for them. Some people are grateful for it, others are bothered by it. I understand both of those reactions. There are times when we feel the weight of grief less heavily when we know others care enough to devote part of their day to the contemplation of our suffering. And there are times when it seems like people tell us about their prayers so that we will think more highly of them. I have yet to figure this all out. I'll just say it now: if you tell me of your sorrows, I will do my best to remember those sorrows in my quiet time, and I will bring them, in silent contemplation, into the presence of my contemplation of the divine.

Make Me A Blessing