environmental philosophy

- This too is related to technology, of course. If the class is focused on video screens, then all the chairs will face the screens, and the classroom might even be structured like a theater. Etymologically, "theater" means something like "a place of gazing," and theaters tend to encourage people to gaze. Sometimes this can work against other activities, like colloquy, small-group interaction, and really anything that involves students moving from one place to another.

- If that last sentence made you ask,"But why do you want your students to move from one place to another?" then you see that we have some pretty strong presuppositions about how education should happen: students should sit and listen, teachers should stand and lecture. This communicates something about authority, and at times that's helpful. But it can also invite students to lean back into passivity, and to assume they have no role in their own education.

- The furniture in classrooms tells us how people are to behave, because it has been made and purchased by people who had in mind some idea of how students should behave. Most wrap-around desks are made for right-handed people, for instance. And most classroom desks I've seen expect students to sit upright, at attention, with a book open in front of them. I really don't like those desks, and I feel trapped when I sit in them. I wonder sometimes how they make my students feel. I wish we had fewer chairs and more sofas. Maybe a fireplace, or some tables with glasses of water, and ashtrays on them. I suppose I wish I could teach in pubs or ratskellers, which are, after all, places consciously designed for people to meet and discuss what most matters to them, informally, passionately, amicably.

- Classrooms that privilege video screens tend to undervalue natural light and windows. I am reminded of Emerson's reflection on a boring sermon he once heard. Emerson wrote, in his Divinity School Address, that while the minister droned on, Emerson looked out the window at the falling snow, which, he proclaimed, preached a better sermon than the minister. I have no doubt that nature can often give a better lecture than I can.

Could a Robot Have a Mystical Experience?

This is something I've been contemplating for a while, for a variety of reasons. It's not that I think that robots are about to have organic religion (that's not for me to say) but increasingly we are delegating small decisions to machines. We should prepare ourselves for times when machines will claim the right to make big decisions. The machines might be making such claims because they are self-conscious, but they might much more easily make such claims because it's easier to sell us products or political views when they come with the stamp of the divine.

It's worth linking back here to a previous post, if only to point out how helpful Evan Selinger, Irina Raicu, and Patrick Lin have been as I think about this. None of them should be blamed for my oddities or errors, but all have helped me to think more clearly.

Ants and Grasshoppers, Wasps and Cicadas

The Ant and the Grasshopper (or Cicada)

We’ve been thinking about cicadas for a long time. In his well-known fable, Aesop compares cicadas to those industrious hymenopterans, the hardworking ants. (Ants, bees, and wasps are all hymenopterans. Sometimes Aesop’s word “cicada” is translated as “grasshopper.”) Bernard Suits' book The Grasshopper reminds us of the timelessness of that comparison, and asks us to consider the place of play in a well-lived life. (Incidentally, there's a playful restaurant in Athens' Syntagma neighborhood called Tzitzigas kai Mermigas.)

Students of ancient Greek Philosophy will remember the cicadas in Plato’s Phaedrus. That text offers us a rare glimpse of Socrates outside the city walls. Cicadas hum loudly overhead when Socrates ironically declares that he is still trying to examine himself, and so he has no time for the cicadas’ sweet song. A little later on, Socrates (again, ironically) returns to the cicadas and suggests that their song is a distraction for those who would examine their lives in conversation with other people. (Aesop: Perry 373; Plato, 230b, 259a)

It’s no surprise to me that cicadas figure in these and other classic texts from around the world. Cicadas are both beautiful and mysterious to the young naturalist. Cicadas spend most of their lives underground. Late in life, they emerge and shed their exoskeleton. Their adult lives will be short, but full of singing, flying, and mating. Not a bad way to go, I think.

Cicadas can also be pests. Their noise can suck the calm out of a summer evening, and these subterranean tree parasites also suck the life out of trees.

The Myth of the Wasps

But it’s not the cicadas that interest me this year. Instead, I’m looking at the hymenopterans. Around this time of year another species emerges with the cicadas: cicada killer wasps (sphecius speciosus).

These two species have a lot in common. Like the cicada, the cicada wasps live underground for most of their lives; they become winged adults around the same time; and they die after mating. The wasps emerge from their burrows with mating fervor and haste. They move fast, darting and banking suddenly. The males joust with one another, constantly changing direction and speed. These are some of the biggest wasps we have, thick as a pencil and up to five centimeters long. They have huge eyes and long, black-and-yellow-striped bodies. They look dangerous.

They look dangerous, but they're not very dangerous to most of us.

Looks Can Deceive, For Good Reason

Contrary to their appearance, they don’t pose much threat to humans. My instinct on seeing huge, fast wasps is to run, or to swat them away. Evolutionarily, this is probably a good instinct. We fear creatures that look like they sting and bite because some of them can hurt us.

When I was a child, that fight-or-flight instinct was strong. Growing up in the Catskill Mountains, I learned to avoid snakes, spiders, and wasp nests, and to be on the lookout for larger predators like bears. One day when I was playing at the wooded edge of our lawn, Dad ran outside to tell my brother and me that one of the neighbors had just seen a bobcat nearby. We were small, and folks were worried. Would a bobcat attack a child? We all eyed the woods warily, and for weeks afterwards we distrusted the forest.

Fighting for Food Is Expensive

In my two decades of teaching environmental studies, I’ve come to realize that most of the creatures I encounter in the wild don’t want to tangle with humans. The wasps are interested in other wasps, and in cicadas. Like my father that day in the Catskills, the wasps are looking out for their families, and in doing so, they’re incidentally tending a garden from which other creatures benefit. As the name suggests, cicada killer wasps hunt cicadas to feed their offspring. By limiting the population of the cicadas, the wasps help the trees, which helps everything that depends on the trees, even the cicadas that survive and mate. Female cicada killer wasps paralyze cicadas with their stinger. Then they drag the cicadas into their burrows. The wasps lay male eggs on single cicadas, and female eggs on multiple cicadas. (The females grow bigger and need more food, so a female egg gets a bigger larder.)

A female cicada killer wasp won’t sting you unless you force her to. Grab her hard and she will fight back. Leave her alone, and she will leave you alone as well. Likewise, the stingless males might seem threatening, but they’re just looking for love, sometimes in the wrong places. The reason why they are flying so fast? They’re competing for mates, and they’re looking for a female who is ready to breed. All of those adults flying around right now will be dead in a few weeks; they’ve got work to do, and little time to do it. All of their children will be born in solitary burrows, lonely orphans. Their parents are doing what they can right now to make sure that those orphans survive. And so the cycle repeats itself.

Why does any of this matter?

First, I’m telling you a little about my work as an environmental philosopher. I don’t just study animal ethics and ocean policy. Much of my time is spent trying to observe the world around me. Like Thoreau and Aristotle before me I want to learn what I can about the lives I share this place with. Some of my research is done in journals and books, but a lot of it is done outdoors. I study salmon in the Arctic, I take my students diving on reefs and trekking through forests, and we spend time just watching the wasps and cicadas here on the prairie.

Second, I want to affirm that your fears of wasps and bees and snakes are natural and even reasonable. That instinct has helped our species survive and to care for our families, just like the instincts of the cicada killer wasps help them. There’s no shame in that.

Which brings me to my third point: the fears may be natural, but firsthand experience and liberal education can go a long way towards moderating those fears. The fears are limbic, buried deep in our genes and brains. But that should not satisfy us; we should take Socrates’ famous words about the examined life to heart, and examine the fears that constrain our decisions.

It’s reasonable to fear wasps in general, but the more you learn about wasps and bees, the more you’ll see that most of them want nothing to do with us. Think about it: we can kill them with a swat. We are giants in comparison to the biggest wasp in the world. For some hymenoptera, stinging us is expensive. Some bees die when their stinger is torn from their body. When wasps sting, they draw on their limited supply of potent toxins. Something similar is true of venomous snakes: it’s metabolically expensive for them to produce venom, and it’s extremely risky for them to attack something as large as an adult human. Most of them, given the choice, will avoid us. I see this in my fieldwork in the far north and the far south, too: many large carnivores like jaguars and brown bears would rather avoid me if they can. Animals, like humans, don’t want to spend more for a meal than necessary.

(Of course, scarcity of food can justify greater expenditure of energy to make sure you have a meal. This is why, as the arctic is losing its ice, polar bears are walking farther and farther in search of food. This year several polar bears have been found an extraordinary distance from the ocean. Hunger can make migrants of us all.)

This brings me to my last point: I’m not just writing about bees and bears, after all, but also about politics. The cicada killer wasps are a living parable, a fable with a moral. You and I have some prudent fears that are built into us.

It makes sense, on an evolutionary scale, to be fearful rather than trusting, and to avoid the unfamiliar. It makes sense to be wary of immigrants whose language, clothing, diet, cultural practices, and aromas differ from those of our friends and family. Likewise, it makes sense to be standoffish when you have had a bad experience with someone who does not walk, talk, or look like the group you most associate with.

Making fresh decisions costs us calories in mental effort, so we save our energy by limiting our social sphere. The echo chamber is comfortable because it’s an easy lift. Anyone who requires you to learn new vocabulary or new ways of thinking about love, family, politics, money, faith, recreation, food, or the other things that make up our lives is someone who costs us the energy we consume in making new decisions.

It’s tempting to look to simple technology to make our lives easier. It would be much easier to build higher walls, spray stronger toxins, create more information filters to choose our reading for us, and never to learn the names of those affected, as though we didn’t share an ecosystem.

As though we were not quite similar to one another. As though we did not all love our families. As though only some of us understood the value of hard work. As though we did not depend on one another. Kill the ones we have called the killers and be done with them.

But if we do so, we remove them from the system we share, and we leave a gap. Without the wasps, the cicadas lose a species that serves their species. If the cicadas multiply, the trees will pay the price. If we kill the wasps, we pass the buck along to the trees, and to everything that depends on them, including ourselves.

The Fable of the Bees, and the Examined Life

In Bernard de Mandeville’s Fable of the Bees, he makes the claim that we are all driven by innate mechanisms and drives. Evolutionary theory backs that up, to some degree, but we’re not just machines.

We’ve got the capacity to examine ourselves, and to learn, and to make some changes. We might all be born with a fear of snakes, spiders, and wasps, but if we take the time to learn about them, and to learn about what drives them, we might find that we fear them less and welcome them more readily.

Could the same be true of our fellow humans who differ from us? For me, at least, this has been one of the best lessons of being an environmental philosopher.

Fellow Gardeners

Recently I was working in my garden here in South Dakota. Two male cicada killer wasps were feeding on the tiny blossoms that are just opening up on my mint plants. One of them, perhaps startled by my arrival in the garden, flew up into the air and bumped into me, then righted himself and flew off. The other sipped nectar and continued to hop around the garden. A moment later, the first one returned. He got over his fear and went back to eating. As they ate, they helped to pollinate the flowers, as so many bees and wasps do. My garden will bloom again next year in part because these “killers” helped me with my gardening.

I’ve also gotten over my fear, although it took me a lot longer than it took that male wasp. Little by little, as I’ve paid attention to the small creatures around me and tried to learn their names, I’ve come to welcome them as neighbors. I’m trying to learn their language, and to appreciate their culture. I’m glad to share the garden with them.

Bristol Bay and Pebble Mine: Mutual Flourishing or Midas' Touch

In this brief commentary I argue that we should prefer long-term mutual flourishing over the prospect of short-term financial gain for a few. The myth of King Midas offers an illustration of what is at risk: the gleam of gold can blind us to the importance of being good stewards of nature, and of being good neighbors and good ancestors:

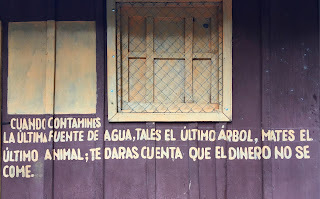

"Not all mining is bad, but to choose a mine that offers gold in exchange for life and mutual flourishing is to display a clear symptom of Midas’ malady. In the ancient myth, King Midas wished for the power to turn all he touched into gold. Half a trillion dollars in ore under the tundra might make us forget what Midas suffered when his wish was granted: he gained great wealth at great cost. When he reached out for food, it turned to inedible gold in his hand. In the case of the Pebble Mine, the risk is not to the PLP, but to the people who are sustained by a four-thousand-year-old tradition of salmon harvesting, and to all the other birds, animals, and plants that depend upon the salmon."I'm reminded of a hand-painted sign I recently came across at a ranger station in El Zotz in Guatemala's Maya Biosphere Reserve.

It reads "When you pollute the last source of water, cut down the last tree, and kill the last animal, you'll realize that you can't eat money."

It would be good to learn that lesson before it's too late for the salmon - and for everything that depends upon them.

You can read my article here.

Butterflies In My Stomach

|

| Kentucky roadside butterfly banquet. Can you see the little one? |

Here is the danger of becoming a professor of Environmental Humanities: people begin to assume that you care about nature, and that you are willing to share what you know.

Both of these things are true, by the way. (Many of my photos of wildlife and nature are here, on my Instagram account. I do care, and I am delighted to share the little I know.)

Over the years, I have come to love insects. This has come about partly through my years studying trout, char, and salmon, and of the places they live. I've spent a good portion of the last decade walking Appalachian waterways from Maine to Georgia. Over that same time, I've walked hundreds of miles through the remaining forests of northern Guatemala and Nicaragua. As both a researcher and teacher I've walked through the mountains of the American West; and I've made similar excursions to the foothills of the Brooks Range, the Kenai Peninsula, and Lake Clark National Park in Alaska.

The fish that I love depend upon the insects, so, like so many people who gaze at salmonids, I have come to know many riparian insects.

Once you study the insects along the streams, you start to notice the other plants and animals that depend upon them, too. In Kentucky I have come upon a steaming pile of bear scat that was full of half-digested cicadas. I've started to notice the wings of insects, left behind by the birds that only eat the fleshy bodies of the bugs they catch.

|

| Butterfly wing, left behind by birds. Guatemala. |

From there, it's not a big leap to realize that if the fish and the birds and the plants need the insects, then so do I. Butterflies and other insects feed the larger animals my species eats, and they pollinate the plants that feed us. All of us have the actions of butterflies in our stomachs. Can you see the lepidoptera in this next photo? There are quite a few of them, resting on the bark of this tree in Petén.

|

| Gray cracker butterflies, Petén, Guatemala. |

Little six-legged creatures feed us all. The small things matter.

And so do my students, even if they're not currently enrolled in one of my classes.

So in the past week I’ve gathered a few hundred of my best butterfly photos to share with my student. This photo is one of the worst in photo quality, but it’s a great image nevertheless:

|

| Butterflies on the ground in Kentucky, 2008. |

I took this nine years ago in the mountains in Kentucky while working on my book on brook trout. Three distinct species of butterflies are gathered here, sipping minerals from the ground. My coauthor Matthew Dickerson and I came upon this arboreal banquet by chance.

I wish I'd had a better camera with me. For now, the blurry image is enough to bring to mind that memory of hundreds of lepidoptera sipping and supping together on the forest floor, filling their bellies with the bare earth before flying off to pollinate flowers that, through a complex net of relationships, would someday fill my belly too.

Wicked Problems in Environmental Policy

a. Do so for their perspectives, for their interests, and for their tools.

b. Ask: Who are the stakeholders?

i. Go beyond the financial stakeholders or stockholders.

ii. Include everyone who affects, or is affected by, the policy under consideration.

c. Remember Charles Peirce’s idea: science is the work of a community, not of an individual.

d. Make concept maps, and use other kinds of visualizations of the problems.

i. This is a way of utilizing a broad range of tools. Don’t just use the tools others tell you are relevant; include the arts and the sciences alike.

ii. Drawing and sketching pictures will help you to see better. As Louis Agassiz said, “the pencil is one of the best eyes.” It is often better than a camera.

iii. Music, literature, poetry, and the visual arts may be just as helpful as the tools offered by STEM fields and policy-making professions like law.

iv. If you include the arts, you wind up including the artists; similarly, if you exclude the arts, you exclude the wisdom and insight of the artists.

v. Include ordinary daily practices. Learn to fish, even if you don’t plan to fish. Hike in the woods, even if you don’t like the outdoors. These are, in a way, practices of paying attention to the world.

e. Include other voices and texts in the conversation, not just the shareholders, but all the stakeholders.

f. Define “stakeholders” as broadly as you can. Include a community across generations. Include the departed and the not-yet-born if possible.

i. Traditions might be full of wisdom, so don’t ignore them, especially if they are specific to a place. Traditions may be inarticulate wisdom that is tested by time.

ii. Plan for seven generations. I sometimes think of this as the difference between planting those crops you will harvest this year and planting hardwood trees so that they will be old-growth trees long after you are dead. Humans – and other species – need both kinds of plants.

|

| Bear scat along a salmon river, Katmai Preserve, Alaska |

2) Second, fill your toolbox—and your community’s toolbox—with bear poop. This is an inside reference my students will understand by the end of the semester, but I'll fill you in briefly: I take the time when I am in the wild to look at animal scat, because it is often a picture of what food is available to the animals, and that, in turn, is a picture of the problems the environment is facing. Paying attention to scat over time gives you a long-term picture of changes to the environment. Poop is a tool that is free, that is right in front of you, and that is easy to overlook as unimportant or distasteful. Bear poop that is full of salmon bones tells me one story; bear poop that is full of berries tells me another. I don't literally fill my toolbox with bear poop, but paying attention to negligible things like bear poop gives me new tools I wouldn't have otherwise. What does this mean for us?

3) Third, have what Peirce calls “regulative ideals”

4) Fourth, don’t expect perfection

5) Fifth, do expect growth, and strive to cultivate good things. This is the work of ethics.

6) Sixth, do expect to be part of a community that continues to work on the problems for a long time.

7) And seventh, don’t give up!

The Trace I Left Behind

Sometimes I get quizzical looks when I say that I, a philosophy and classics professor, am researching fish. Let me explain.

I teach environmental philosophy and a range of classes in what I call "environmental humanities." These include courses in environmental ethics, nature writing, philosophy of nature, and even a course on environmental law and policy for first-year undergraduates, as an introduction to being a university student.

I also teach courses in field ecology, including a monthlong course in tropical ecology in Guatemala and Belize. I teach in Greece over my spring break, and this year we will be looking at the expansion of fish farms in the Mediterranean and how fishing has changed there over the last six thousand years.

Closer to home, I teach and practice what Norwegians call friluftsliv, or life in the free air. Whenever possible, I teach outdoors. Most years, I take my ancient philosophy students camping in the Badlands National Park to watch the Orionid meteor shower while we lie on sleeping bags under the stars.

In all of this, my aim is to make sure that nature is not an abstraction to my students, nor to me. I want to know the places the fish live, the grasslands the bison roam, the forests where the jaguar and the ocelot hunt, the tundra rivers where the Dolly Varden chase the salmon under the watchful gaze of the bears.

In other words, my aim is to stay in contact with wildness, and to do so in a way that allows me to take something valuable home: intimate knowledge. I am not a scientist, so I don't bring samples back to a laboratory. I do bring home photographs, and I do spend a lot of time making observations of the places I work, so that I can bring home notebooks full of writing to share with my students. And of course, I write books and articles to share with others.

This summer, I was sorely tempted to bring something else home from Lake Clark: a tiny fossil. I had chartered a float plane to take me to a fairly remote lake, and there my fellow researchers and I walked the shore to the mouth of a stream full of spawning salmon and rainbow trout.

|

| Salmon preparing to spawn |

As I often do, I sat down on the gravel and started to turn over rocks to see what invertebrates were living there. The salmon are bright red and eye-catching, but the bugs and spiders tell an important part of the story of a place, as Kurt Fausch has written about in his recent book, For The Love Of Rivers. Who was it - J.B.S. Haldane, perhaps? - who quipped that God has "an inordinate fondness for beetles." The world is full of wonderful, tiny lives that are easy to overlook.

I don't try to bring beetles home, but one insect tempted me this summer. Really, it was just a trace of an insect, just the trace of its wings, in fact. I can't even tell you what insect it was. All I can tell you is that somewhere near that river, probably millions of years ago, something like a dragonfly died in the mud, and the river graced its delicate wings with the cerement of silt. That silt took the form of the wings, those wings left a fingerprint - a wingprint - on the earth. And this summer, I found that print, that delicate, wonderful trace.

|

| Fossilized trace of an insect's wing |

While my son and my friend and our pilot walked, I sat with that stone in my hand and thought about pocketing it. Here I was in the wilderness, and no one would know. It's one tiny stone in the largest state in the union; who would miss it?

Ah, but it is one tiny stone that does not belong to me. It is one tiny stone in a vast wilderness that belongs to all of us, and to all who will come after us. It is one tiny piece of rock with an incomplete fossil of a little odonata. The river there has held it and cared for it since time immemorial.

Now I am back in South Dakota, but a tiny trace of my heart remains along the strand of that stream in Alaska. It lies there, wrapped around that delicate trace of insect wing, and I will never find it again in that vast wilderness.

But perhaps someone else will. Until then, perhaps it is best not to let Midas' longings turn our hearts to stone too soon. Let's walk the shores together, I will continue to say to my students. And let's bring something intangible home in our memories. And let's do the hard work of leaving behind the beautiful, delicate traces that wildness has safeguarded for so many, many years.

A Pretty Good Year

As my regular readers know, I'm a professor of philosophy and classics, and I teach a wide range of classes. (You can click on the "Teaching" link above to see a sampling of the courses I teach.)

Often people assume that means I wear tweed and a bowtie and that I spend my time in classrooms talking about old books. All that is true, but it's only a part of what I do.

In fact, most of my favorite classrooms are outdoors, where I'm likely to be found wearing jeans and hiking boots, a parka, or a wetsuit and snorkel.

Over the last dozen years or so my teaching and research have tended towards the environmental humanities. Think of this as the merging of the humanities side of the liberal arts with a close observation of the natural world. I consider my work to be a continuation of the work that Thales and Aristotle did when they paid close attention to animals on the ground and to the skies above, and of the work of Peirce, Thoreau, and Bugbee, all of whom let a rising trout or a solar eclipse provoke philosophical reflection.

While I don't work in an indoor laboratory, I think that education is not about the imparting of information or the filling of an empty vessel with ideas. Education is the kindling of a fire, as Plutarch wrote. And that fire is kindled by the kinds of experiences that we get in labs, art studios, shared meals, liturgies, study travel, and seminars. Lecture halls are a fine place to discuss environmental policy, to be sure. But so is a prairie, especially when you're waiting for water to boil on your camp stove, and watching the sun's beams break over the horizon and melt a light frost on your tent.

When I'm at home, I like to take my classes outside to sit under trees on campus. In the fall, I try to bring my Ancient Philosophy students camping in the Badlands of South Dakota where we can view the stars far from urban glow. Most Januaries, my students and I are in the subtropical forests of Guatemala and on a barrier island in Belize, studying ecology and culture. I rarely take a spring break, since I usually take that week to teach a course in Greece. Last summer I started teaching a class on trout and salmon in Alaska.

Those are all beautiful, memorable places, but I don't visit them as a tourist. I go to these places because I want my students to understand what is at stake when we talk about environmental regulations and practices. I want them to meet displaced people whose permafrost islands are melting or whose forests are being burned down for meager cropland. I want them to see the disappearing mangroves so that they can consider the full cost of seafood. When they stay in homes in Guatemala, my students will meet people who can never again be a mere abstraction; after we return, my students will know that the people struggling to cross borders are not nameless, faceless strangers, but people who are looking for ways to feed those they love.

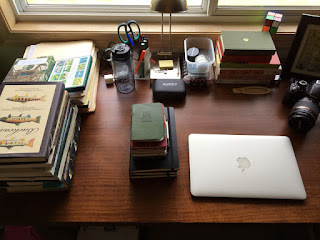

A little less than a year ago I was finishing up a year that had brought me to all these places. I taught in the South Dakota Badlands, in Central America, in Greece, and in Alaska. Along the way, I had begun studying environmental law at Vermont Law School as a way of enhancing my teaching and my research. It was a good year, and as August was winding down, my desk was covered with field notebooks full of observations from Alaska and Guatemala, ready to be written up. My field notes are usually accompanied by thousands of photographs, and hundreds of sketches. I began the fall semester last year ready to teach, and ready to write.

|

| Field notes. A picture of some of the work I do when I'm inside, and not teaching; or, if you like, a picture of my desk as I recover from my injuries. I have a lot of catching up to do. |

And then I wound up in the hospital with some serious injuries. Those injuries put a sudden stop to all my teaching last fall, and for a long time I lost most of my ability to write. (I'll try to write more about the injuries and my subsequent disabilities later; it's not an easy thing to write about yet.)

Now, as this summer hastens towards the beginning of another school year, I am able to look back on last year with a sense of good fortune - albeit mixed with one very bad day and its long-term consequences. Physically, I'm regaining my flexibility and strength, a little at a time. I'm not where I was a year ago, and I may never be there again, but I'm alive and able to walk, so I'll count that in the "win" column of my life's scorecard. Intellectually, most people seem to think I'm doing fine, so I'll also count that as a win. Although it left me exhausted each day, I was able to teach again this spring, and I plan to be back in my classrooms (Deo volente!) this fall.

But here are these field notebooks, and hundreds of unedited pages on my hard drive. It was my habit to write daily. Over the last year, recovering from a brain injury has made it hard to write more than a few sentences at a time.

This morning I was looking at some of my pictures from my research in the Arctic last summer, and I was hit with a feeling of loss. Those photos and those notes should be a book by now, and perhaps several articles and book chapters, too. Instead, over the last year, as I have waited for my body and brain to heal, and as I struggled to do my teaching, I had no strength to write.

It feels funny to say that, but perhaps I am not alone in finding that a brain injury can be slow to heal and extremely tiring. I don't say that to get your sympathy. I am blessed with a very supportive community and an amazing wife who somehow has kept our life together and nursed me through my healing process. I'm fortunate. But if you've read this far, you might consider whether there are others around you who look like they're doing well physically but who might be nursing invisible wounds or who might be struggling to cope with invisible disabilities. This past year has given me a new perspective on that by making me aware of my own disabilities, most of which you won't notice if you see me at the gym or in one of my classrooms.

I might not be able to write another book yet, so for now, here's my plan: I'll write a little at a time. Thankfully, I've got my notes, sketches, and photos. I'll start with them.

If you're curious about how a professor of philosophy and classics does research and writing about nature - and how he works to recover from a serious brain injury - you might check out some of my recent publications. My book Downstream is the result of eight years of field research on the ecology of the Appalachians, with a focus on brook trout. On this blog you'll also find my recently published poem, "Sage Creek," which might give you a glimpse of my ancient philosophy class camping and stargazing in the Badlands. Or feel free to look at my photos on Instagram. Even when I can't teach in the field, I can still wander my garden with a hand lens and camera.

Poem: Sage Creek

Here are the first few lines:

Halfway through the fall we drive west, far from urban glow,You can read it all here.

To see the stars that we have never seen at home.

We go to the Badlands, at night, to the primitive campground

And listen to the coyotes singing from rim to rim

Of the valley where we are trying to sleep.

The voices of three packs rise like questions:

Who are you? What are you doing here?

*****

Sage Creek

Halfway through the fall we drive west, far from urban glow,

To see the stars that we have never seen at home.

We go to the Badlands, at night, to the primitive campground

And listen to the coyotes singing from rim to rim

Of the valley where we are trying to sleep.

The voices of three packs rise like questions:

Who are you? What are you doing here?

Weary from driving, observe how much you want to stay awake

Now that you are here. Explain

And give examples

From all your senses.

If the wind blows across sage, then what follows,

and how do you first know it?

What is the feeling of the prairie wind at night,

And why is it now new to you?

Dry weeds crunch under sleeping bags stretched out under the cold, living sky.

Our arms swing to point at Orionid flares.

We speak in the whispers of worshipers entering a cathedral for the first time.

How long have we lived here,

On the prairie, and never felt it on our skin, all night long?

Compare and contrast

The Milky Way.

Before tonight, you have never seen it turn.

Consider all the stars,

And the difference between reading about them and watching them slowly slip across the sky.

Wake to the feeling that it is not yet dawn, but no longer night.

With your eyes still closed, ask yourself how you saw it,

How this dry land exposes you to yourself.

For a little while, you hold your eyes closed,

And remember the bright green lines of shooting stars.

Holding still, you listen:

This is the sound of bison, breathing. Nearby

The staccato chickadee and the whirling meadowlark

Greet the new day

In this place we have so long avoided.

The prairie dogs at the edge of the campground eye us warily, and bark a warning

As we load the car for the drive home.

*****

David L. O’Hara

(2015)

Printed in Written

River, Issue 10, 2016, Hiraeth Press.

The whole issue might be available on Kindle, here.

Wendell Berry: Past A Certain Scale, There Is No Dissent From Technological Choice

-- Wendell Berry, “A Promise Made In Love, Awe, And Fear,” in Moral Ground: Ethical Action For A Planet In Peril. Kathleen Dean Moore and Michael P. Nelson, eds. (San Antonio: Trinity University Press, 2010) p. 388.

My Backyard Ark

Augustine once said that a key to his conversion was when he met St Ambrose. Augustine had regarded the Bible as full of flawed and problematic texts. As Augustine put it, "by taking them literally, I had found them to kill."(1) Ambrose taught Augustine that the texts of the Bible may have more than one sense. The scriptures might speak to him in more than one way. When he heard this, and heard it from a man who thought it important to study science and the liberal arts, Augustine found his spiritual home in Christianity.

Augustine once said that a key to his conversion was when he met St Ambrose. Augustine had regarded the Bible as full of flawed and problematic texts. As Augustine put it, "by taking them literally, I had found them to kill."(1) Ambrose taught Augustine that the texts of the Bible may have more than one sense. The scriptures might speak to him in more than one way. When he heard this, and heard it from a man who thought it important to study science and the liberal arts, Augustine found his spiritual home in Christianity.In recent years authors like Norman Wirzba, Bill McKibben, and Scott Russell Sanders have written about the relevance of Biblical texts for thinking about ecology. To me, they have been a little like St Ambrose. I've found one passage in Sanders to be quite helpful personally as I think about the management of my little suburban fifth-acre plot.

In his A Conservationist Manifesto, Sanders writes about the story of Noah and the Ark. He remembers that Noah was given the task of saving not just himself but every other species as well. And once they were on the ark, it was his job to care for the animals and to keep them alive. Sanders talks about books, and communities, and practices that can be like small arks in our time. One such "ark" may be the little plots of land we maintain around our homes:

"Every unsprayed garden and unkempt yard, every meadow, marsh, and woods may become a reservoir for biological possibilities, keeping alive creatures who bear in their genes millions of years; worth of evolutionary discoveries. Every such refuge may also become a reservoir for spiritual possibilities, keeping alive our connection with the land, reminding us of our origins in the green world."(2)Lately I've been surveying my yard more closely, looking to see whom I'm sharing it with, and how. I've been trying to do some phenology, like Thoreau did. I also wander my garden with lenses: a hand lens for close inspection; my phone camera and my SLR for keeping records of what lives and grows there; and I've recently set up an infrared game camera to see who passes through at night. For the curious, I've posted some photos below of what I've seen there.

*****

(1) Augustine, Confessions. Henry Chadwick's translation. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998) p. 88.

(2) Scott Russell Sanders, A Conservationist Manifesto. (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2009) p. 16.

*****

All of these images were taken by David O'Hara in the fall of 2013. You may use them elsewhere but please mention where you found them and give credit where it is due. Thanks.

Animal Sacrifice And Factory Farming

“In the period of the history of the Christian Church, we have traveled from a time in which the killing of animals was only permitted within religious rituals to a time in which 60 billion animals per year are killed for human consumption, the majority of which are raised, slaughtered and processed in factory conditions far removed from the sight or concern of their consumers.”

David L. Clough, On Animals: Volume I, Systematic Theology (London: T&T Clark, 2012) (xiii)

Teaching Outdoors

|

As early as middle school I knew I wanted to become a college professor, and I love my job. It is a delight to spend time with young people who are curious, after all.

Years ago, my friend Matt Dickerson pointed out to me that it's also my job to help those who are not curious to see why they should be. As it turns out, that work is usually delightful, too, a rewarding challenge.

So on the whole, I love my work.

But I admit I don't love classrooms, for several reasons:

First, no matter what decade, every classroom I've been in has exhibited an unhealthy tendency towards becoming cluttered with the latest technology, and most of that tech seems to take up a lot of space and to become the center of attention. I'm not opposed to technology in the classroom, not at all. But I'm opposed to letting it get in the way, as it does when the "Smart Cart" leaves me no room for my lecture notes, or when I can't seem to turn the ceiling-mounted projector on or off. I'm a fan of chalk, because chalk allows spontaneity, and it allows for much more than alphanumeric writing in neat rows. Sadly, concerns about chalk dust getting into computers is threatening to make chalkboards disappear from my classrooms. Alas. Chalk is an excellent technology, and if it vanishes, I will mourn its loss.

Second, classroom architecture is not some value-free, neutral design. Classroom architecture makes a big difference in how people teach, and how they learn:

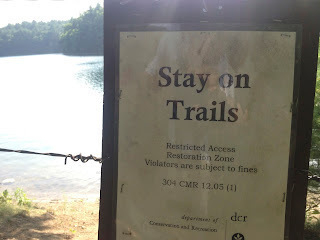

|

| Step off the trails! Explore! An ironic sign at Walden Pond. |

And this is why I am a preacher of the importance of study abroad. Not just travel, but serious, engaged, rigorous study in the classroom of life in another place. This is why I teach Classics in Greece every year, and why year after year I take students to Central America to study environmental philosophy and ecology.

More and more I've been trying to shift the learning focus in my classes from the classroom to the laboratory - where by "laboratory" I mean anywhere that allows students to learn with their whole person. I make my ancient philosophy students devote hours each semester to star-gazing, in part because this is what the ancients did, and in part because I don't want them to miss the stars. I want them to gaze in wonder at the firmament so that when they read Aristotle and Galileo they know that they've looked at what those great minds saw as well. We even occasionally take field trips to really dark places like the South Dakota Badlands so we can see the skies even better.

My environmental philosophy students must observe a square meter of earth for a semester, spending an hour at a time without a camera, drawing and writing about what they see, because it does not make sense to me to talk about the earth when you have not taken the time to sit upon it, to listen to it, to smell and taste it, and to see what other lives creep, and walk, and fly across it.

My friend Aage Jensen advocates the Norwegian philosophy of Friluftsliv, life and education outdoors. And when he organizes a conference on it, he eschews conference centers and holds the conference while walking through the mountains, or paddling a river. Because he believes that one should practice what one preaches, and that nature is always ready to teach.

To paraphrase the Stoic Musonius, teachers would do well to talk less and to take their students with them into the fields, because there they will learn far better and far more than in the lecture hall.

|

| Nature is full of things worth seeing. |

The Howler Monkeys of Petén, Guatemala

|

| One of the wonders of the Mayan Biosphere Reserve |

During one of my last trips I made this video. We were setting up camp in the Mayan Biosphere Reserve, or Biosfera Maya, en route to Tikal, when several troops of howlers began to sing nearby. We followed the voices to one of the nearest troops so we could get a closer look at these gentle beauties, our placid arboreal cousins. Enjoy the sound.