Epimenides

∞

Written On The Skin

One of the peculiar things about teaching Greek and knowing several other ancient languages is that people often come to me seeking help with tattoos.

A few years ago a student named Brian came to me and asked "How do you say 'Suck Less' in Greek?" Apparently this was a phrase that his running coach said to his team to inspire them to run better.

As crude as the phrase is, I was intrigued by the problem of translation. "In order to translate the phrase I'd have to know what you mean by it," I replied. I spent a little while explaining how it would be possible to say, for instance, that an infant should nurse less; or that one should inhale less strongly. Or, if you pursue the more colloquial usage of the verb "suck," you might decide that it refers to poor behavior or - ahem - to a kind of erotic pleasure-giving in which the giver is thought to be demeaned by the giving.

Eventually I made the case that if you want to say it in Classical Greek, it would make sense to say it in a way that attended to the use of words in that language, and pointed him to Plutarch's Sayings of Spartan Women as a source of pithy sayings about living and acting strenuously. Ever since I took my first Greek class with Eve Adler at Middlebury College years ago, I've liked the phrase η ταν η επι τας, (at the link above, see #16 under "Other Spartan Women"; click on the Greek flag to see the full Greek text) which is often translated "Come back with your shield or upon it," meaning "Act virtuously in battle; either die with your weapons or win with your weapons, but do not throw them away in order to win your life at the expense of your virtue." I like the Greek phrase for its Laconian pithiness.

Of course, that one didn't quite make sense for a runner, so I showed him another from the same collection, κατα βημα της αρετης μεμνησο, or "With every step, remember [your] virtue." ("Virtue" is not a perfect translation; you could translate it as "excellence" also.)

Three years have passed since that conversation with Brian, but a few months ago he tracked me down and showed me his tattoo, which I rather like:

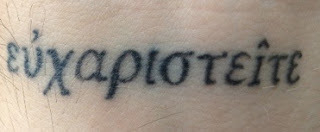

In a new twist, last year another student asked me to help him find the Greek verb "give thanks" as it appears in I Thessalonians 5.18. He didn't tell me what he planned to do with it, but when I saw him later that year at a wedding he showed me this, which he has tattooed on his wrist:

The word you see is ευχαριστειτε, related to our word "Eucharist" and the modern Greek ευχαριστω, meaning "I thank you."

I say this is a "new twist" because at least one passage in the Hebrew scriptures (Leviticus 19.28) appears to prohibit tattooing one's skin. Getting a tattoo, and in particular getting a tattoo of scripture, offers a bit of insight into one's hermeneutics. If the Gospels prohibited tattoos, I doubt many Christians would get them, but since the prohibition comes in the Hebrew scriptures, and since it seems to be tied to particular practices of worship or enslavement that no longer seem relevant, many young Christians are untroubled by it.

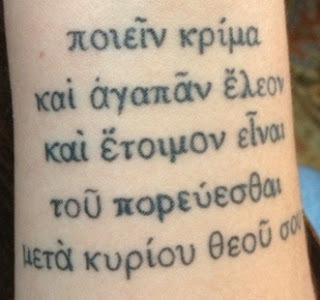

Recently one of my advisees showed me one of several tattoos she has recently acquired. This one is a longer Biblical text, from the prophet Micah, chapter 6, verse 8. I thought it interesting that she chose to get the Septuagint Greek rather than the Hebrew. She knows and translates Biblical (Koine) Greek and so I suppose she felt closer to that language. The text below means "...to do justice and to love mercy and to be ready/zealous to walk humbly with the Lord your God."

I like that verse quite a lot. If you don't know it, it begins by saying that this is what God asks of people. It's the sort of description that makes religion sound less like a burden and more like a description of a life well-lived.

I'm always reluctant to give advice about tattoos, because they're so permanent and so personal. And when I do give advice, I always want to write footnotes about regional dialects and historical and textual variants, or about the difficulties of translation. Quotes out of their native context so often seem lonely to me - such is my academic habit, of always seeing texts as living and moving and having their being* in nests and webs of other texts. Perhaps that's why I've never been inked myself, and I doubt I ever will get a "tat." I'm just not confident I've found words or an image that I'd want written on me forever. Sometimes that feels virtuous because it's prudent; other times I wonder if that's not a moral failing on my part, like I should be willing to commit to something. But I think for now I will remain uninked, and will continue to admire the commitments of my students.

* For example: I am borrowing this phrase ("live and move and have their being") from St Paul in Acts 17.28; he, in turn, appears to be borrowing it from Epimenides, who writes Εν αυτω γαρ ζωμεν και κινουμεθα και εσμεν. The phrase winds up being used in a number of other places, having been so eloquently translated into English by the King James Version of the Bible. See, for example, its use in the Book of Common Prayer, and in the first line of the hymn "We Come O Christ To Thee."

A few years ago a student named Brian came to me and asked "How do you say 'Suck Less' in Greek?" Apparently this was a phrase that his running coach said to his team to inspire them to run better.

As crude as the phrase is, I was intrigued by the problem of translation. "In order to translate the phrase I'd have to know what you mean by it," I replied. I spent a little while explaining how it would be possible to say, for instance, that an infant should nurse less; or that one should inhale less strongly. Or, if you pursue the more colloquial usage of the verb "suck," you might decide that it refers to poor behavior or - ahem - to a kind of erotic pleasure-giving in which the giver is thought to be demeaned by the giving.

Eventually I made the case that if you want to say it in Classical Greek, it would make sense to say it in a way that attended to the use of words in that language, and pointed him to Plutarch's Sayings of Spartan Women as a source of pithy sayings about living and acting strenuously. Ever since I took my first Greek class with Eve Adler at Middlebury College years ago, I've liked the phrase η ταν η επι τας, (at the link above, see #16 under "Other Spartan Women"; click on the Greek flag to see the full Greek text) which is often translated "Come back with your shield or upon it," meaning "Act virtuously in battle; either die with your weapons or win with your weapons, but do not throw them away in order to win your life at the expense of your virtue." I like the Greek phrase for its Laconian pithiness.

Of course, that one didn't quite make sense for a runner, so I showed him another from the same collection, κατα βημα της αρετης μεμνησο, or "With every step, remember [your] virtue." ("Virtue" is not a perfect translation; you could translate it as "excellence" also.)

Three years have passed since that conversation with Brian, but a few months ago he tracked me down and showed me his tattoo, which I rather like:

In a new twist, last year another student asked me to help him find the Greek verb "give thanks" as it appears in I Thessalonians 5.18. He didn't tell me what he planned to do with it, but when I saw him later that year at a wedding he showed me this, which he has tattooed on his wrist:

The word you see is ευχαριστειτε, related to our word "Eucharist" and the modern Greek ευχαριστω, meaning "I thank you."

I say this is a "new twist" because at least one passage in the Hebrew scriptures (Leviticus 19.28) appears to prohibit tattooing one's skin. Getting a tattoo, and in particular getting a tattoo of scripture, offers a bit of insight into one's hermeneutics. If the Gospels prohibited tattoos, I doubt many Christians would get them, but since the prohibition comes in the Hebrew scriptures, and since it seems to be tied to particular practices of worship or enslavement that no longer seem relevant, many young Christians are untroubled by it.

Recently one of my advisees showed me one of several tattoos she has recently acquired. This one is a longer Biblical text, from the prophet Micah, chapter 6, verse 8. I thought it interesting that she chose to get the Septuagint Greek rather than the Hebrew. She knows and translates Biblical (Koine) Greek and so I suppose she felt closer to that language. The text below means "...to do justice and to love mercy and to be ready/zealous to walk humbly with the Lord your God."

I like that verse quite a lot. If you don't know it, it begins by saying that this is what God asks of people. It's the sort of description that makes religion sound less like a burden and more like a description of a life well-lived.

I'm always reluctant to give advice about tattoos, because they're so permanent and so personal. And when I do give advice, I always want to write footnotes about regional dialects and historical and textual variants, or about the difficulties of translation. Quotes out of their native context so often seem lonely to me - such is my academic habit, of always seeing texts as living and moving and having their being* in nests and webs of other texts. Perhaps that's why I've never been inked myself, and I doubt I ever will get a "tat." I'm just not confident I've found words or an image that I'd want written on me forever. Sometimes that feels virtuous because it's prudent; other times I wonder if that's not a moral failing on my part, like I should be willing to commit to something. But I think for now I will remain uninked, and will continue to admire the commitments of my students.

*****

* For example: I am borrowing this phrase ("live and move and have their being") from St Paul in Acts 17.28; he, in turn, appears to be borrowing it from Epimenides, who writes Εν αυτω γαρ ζωμεν και κινουμεθα και εσμεν. The phrase winds up being used in a number of other places, having been so eloquently translated into English by the King James Version of the Bible. See, for example, its use in the Book of Common Prayer, and in the first line of the hymn "We Come O Christ To Thee."

*****

Update: a week or so after posting this I ran into the mother of one of the people whose tattoos are shown above. She thanked me, though I am not sure whether she was thanking me for helping her son get a tattoo, or for helping him to get the grammar right.

∞

Pragmatist Scripture: Peirce and The Book of Acts

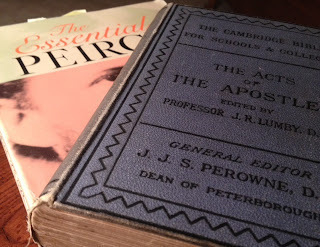

A few months ago a friend who is interested in both scripture and philosophy asked me which scripture mattered most to Charles Peirce. One obvious answer would be the writings of John, the gospeller of agape love, since agape plays such a great role in Peirce's philosophy.

The Book of Acts has recently come to mind as another strong candidate, for several reasons. I plan to write about all this in more detail soon, but I'll use this space to jot down my thinking quickly, in order to make it available to anyone who might be interested, in the Peircean spirit of shared inquiry.

The Greek title of the Book of Acts is Praxeis Apostolon, or the Deeds of the Apostles. We guess that the author of the text was the same as the author of the Gospel attributed to Luke. The title might well have been added after the book was in circulation for a while, but that's probably inconsequential. It occurred to me recently that this text begins with reminding us that the author wrote a previous book about "the things Jesus began to do and to teach," and then it narrates, without further introduction, the things that the first Christians did after Jesus' death and resurrection.

In other words, it is a book of acts, of deeds. It is a book of narratives about what people did.

Which is to say that it is not primarily a book of prayers, or of songs, or of doctrines. It tells a story, without much attempt to interpret that story. And it is the story of a community learning to work together, and learning how it must adjust its doctrines in light of the community's expansion across and into cultures, and in light of the surprising things they find the new community is empowered to accomplish.

This is appealing to Pragmatists like Peirce, who are more concerned with the way decisions lead to actions than with fixing metaphysical doctrines and whose notions of truth, ethics, and metaphysics are more experimental and transactional than systematic and permanent. Pragmatists are given to the idea that it is good for communities to work with tentative, revisable and fallible tenets, ever striving to improve their practices as the community grows.

*****

Peirce is not exactly easy to read, which helps to explain why most of what he wrote remains unpublished even a century after his death. Nevertheless, the patient reader of Peirce is often rewarded by a writer who took words very seriously.

Some of the words he used to great effect in his lectures and essays are derived from the Book of Acts. Among these phrases are a phrase he uses in his 1907 essay "A Neglected Argument For The Reality Of God," and one that comes at the end of his Cambridge Conference Lectures of 1898. The phrases are "scientific singleness of heart," and "things live and move and have their being in a logic of events." See Acts 2.46 and 17.28 for the sources of these two phrases. (The first one might also have come to Peirce through the Anglican Book of Common Prayer, as I have argued elsewhere.)

Two such phrases are not enough to make the case that Peirce was dependent on the Book of Acts, but thankfully that's not the case I'm trying to make. Peirce was well read and he cited other portions of scripture and, of course, many other books, after all. I only want to suggest that Peirce might have found the Book of Acts to be a scripture that resonates with his Pragmatism.

*****

That being said, I wish to point to one figure in the middle of the Book of Acts who might be taken to be a kind of Pragmatist saint: Epimenides.

I won't belabor that point here, as I have already written about it elsewhere. I'll only add that Epimenides appears to be the unnamed source that St Paul appeals to and cites in Acts 17.28.

The Book of Acts has recently come to mind as another strong candidate, for several reasons. I plan to write about all this in more detail soon, but I'll use this space to jot down my thinking quickly, in order to make it available to anyone who might be interested, in the Peircean spirit of shared inquiry.

The Greek title of the Book of Acts is Praxeis Apostolon, or the Deeds of the Apostles. We guess that the author of the text was the same as the author of the Gospel attributed to Luke. The title might well have been added after the book was in circulation for a while, but that's probably inconsequential. It occurred to me recently that this text begins with reminding us that the author wrote a previous book about "the things Jesus began to do and to teach," and then it narrates, without further introduction, the things that the first Christians did after Jesus' death and resurrection.

In other words, it is a book of acts, of deeds. It is a book of narratives about what people did.

Which is to say that it is not primarily a book of prayers, or of songs, or of doctrines. It tells a story, without much attempt to interpret that story. And it is the story of a community learning to work together, and learning how it must adjust its doctrines in light of the community's expansion across and into cultures, and in light of the surprising things they find the new community is empowered to accomplish.

This is appealing to Pragmatists like Peirce, who are more concerned with the way decisions lead to actions than with fixing metaphysical doctrines and whose notions of truth, ethics, and metaphysics are more experimental and transactional than systematic and permanent. Pragmatists are given to the idea that it is good for communities to work with tentative, revisable and fallible tenets, ever striving to improve their practices as the community grows.

*****

Peirce is not exactly easy to read, which helps to explain why most of what he wrote remains unpublished even a century after his death. Nevertheless, the patient reader of Peirce is often rewarded by a writer who took words very seriously.

Some of the words he used to great effect in his lectures and essays are derived from the Book of Acts. Among these phrases are a phrase he uses in his 1907 essay "A Neglected Argument For The Reality Of God," and one that comes at the end of his Cambridge Conference Lectures of 1898. The phrases are "scientific singleness of heart," and "things live and move and have their being in a logic of events." See Acts 2.46 and 17.28 for the sources of these two phrases. (The first one might also have come to Peirce through the Anglican Book of Common Prayer, as I have argued elsewhere.)

Two such phrases are not enough to make the case that Peirce was dependent on the Book of Acts, but thankfully that's not the case I'm trying to make. Peirce was well read and he cited other portions of scripture and, of course, many other books, after all. I only want to suggest that Peirce might have found the Book of Acts to be a scripture that resonates with his Pragmatism.

*****

That being said, I wish to point to one figure in the middle of the Book of Acts who might be taken to be a kind of Pragmatist saint: Epimenides.

I won't belabor that point here, as I have already written about it elsewhere. I'll only add that Epimenides appears to be the unnamed source that St Paul appeals to and cites in Acts 17.28.