exercise

∞

College Athletics: Cui Bono?

This Strange Marriage of Athletics and Academics

This week I've been considering the place of sports on American university and college campuses. (See here and here for the other pieces I've written on this this week.)

If you grow up here, it doesn't seem at all strange, because it's simply how things are. But a little reflection suggests that the juxtaposition of academics and athletics is a little strange.

I say it is "a little" strange because throughout the ages thoughtful people have said that the two complement each other. Plato's Republic discusses the relationship between gymnastics for the body and philosophy for the mind, for instance. Of course, Plato, famous for his irony, is never wholly straightforward, and the target he is aiming at is probably something else, but the characters in his dialogue act as though bodily exercise and mental exercise are related.

Walking, Playing, and Thinking

One of Socrates' other students, Xenophon, wrote in his Cynegetica that the best education comes through learning to hunt, and that book-learning should only come after a boy has learned the art of coursing with hounds, and practiced it in the country. And there are many others who tell us that moving our bodies and learning go together: Maria Montessori reminds us that the work of children is play. Philosophers as diverse as Aristotle, Nietzsche, C.S. Lewis, Henry Thoreau and Charles S. Peirce tell us that walking and thinking are natural companions.

So the strangeness of the marriage of learning and playing is not the hypothesis that the body and the mind work both need exercise. The strangeness is the way we pursue - or, just as often, fail to pursue - that hypothesis. We are told that movement helps us think, and that playing team sports teaches us virtue. If all that is true, then why do we not encourage all students to play sports?

The Irony: We Do Not Practice As We Preach

Speaking of irony, consider this: What we claim and what we actually do are at odds with one another. We say sports are good for everyone, then we expect coaches to eliminate all but the best athletes from their instruction. Rather than advertising our schools as places where students can get an excellent physical education we expect our coaches to travel far and wide to recruit only the best athletes, i.e. those who need the least instruction and who are most likely to win competitions. It is fairly obvious that, rather than using athletics as a means of inculcating virtue and fostering better thinking, we use athletics to gain honor through victories.

And of course, this is obvious to us. We want to win games because winning is a form of advertising. For good or ill, we accept the fact that high school students will often choose our school in order to participate in the glory of competitions won. But we continue to give the other justifications for participation in athletics, perhaps because we perceive that it would be crass to come right out and say "Come to our college and bask in the glory won by others. It will thrill you, and it might help your job prospects," or "We hope that the victories of our athletes will help us to raise money from people who won't give unless we are winning games."

I don't want to be cynical about this. As I have suggested above and said directly in my previous posts, I'm in favor of athleticism. What troubles me about it is the way that certain college sports become increasingly professionalized. Why, after all, are student athletes considering unionizing? That's something employees do, not students.

Let Everyone Learn To Play

My conclusion is not to push for the elimination of college athletics, but for athletics to be brought more into line with the best reasons for preserving it. If playful exercise makes us better people and better students, then let's urge more students to play. Let's give less attention to inter-collegiate competition and more attention to teaching lifetime sports that will allow our alumni to enjoy the benefits of physical activity for the remainder of their lives. Let's teach poorer students to play golf so that when they enter the business world they aren't at a disadvantage when deals are made on the fairway. Let's teach everyone to swim. Let's take all our students on walks - serious walks, cross-country walks. Let's teach them what Thoreau calls the art of sauntering.

Playful activity takes many forms. We should resist the temptation to think of it as the pursuit of a ball. Swimming, hiking, rock climbing, Tai Chi, dance, yoga, and numerous other activities have the same moral and intellectual benefits as team sports. There should be as many opportunities for vigorous play as there are bodies.

Some of my friends have balked at this, understandably. Not all of us are athletic, or at least not all of us feel athletic. But I think a good deal of this is because many of us learned about athletics in a victory-oriented environment. That environment fosters a narrow and shallow view of the active human life. We may not all be quarterbacks, point guards, shortstops, or strikers, but all of us can be active within the limits of the bodies we have been given. If activity is good for us, then we should treat it as good for all of us. Play should not be limited to the activity of a few for the thrill of the inactive many. Play should be, as Peirce said, "a lively exercise of our powers," whatever those powers may be. And it should be a delight.

This week I've been considering the place of sports on American university and college campuses. (See here and here for the other pieces I've written on this this week.)

If you grow up here, it doesn't seem at all strange, because it's simply how things are. But a little reflection suggests that the juxtaposition of academics and athletics is a little strange.

I say it is "a little" strange because throughout the ages thoughtful people have said that the two complement each other. Plato's Republic discusses the relationship between gymnastics for the body and philosophy for the mind, for instance. Of course, Plato, famous for his irony, is never wholly straightforward, and the target he is aiming at is probably something else, but the characters in his dialogue act as though bodily exercise and mental exercise are related.

Walking, Playing, and Thinking

One of Socrates' other students, Xenophon, wrote in his Cynegetica that the best education comes through learning to hunt, and that book-learning should only come after a boy has learned the art of coursing with hounds, and practiced it in the country. And there are many others who tell us that moving our bodies and learning go together: Maria Montessori reminds us that the work of children is play. Philosophers as diverse as Aristotle, Nietzsche, C.S. Lewis, Henry Thoreau and Charles S. Peirce tell us that walking and thinking are natural companions.

So the strangeness of the marriage of learning and playing is not the hypothesis that the body and the mind work both need exercise. The strangeness is the way we pursue - or, just as often, fail to pursue - that hypothesis. We are told that movement helps us think, and that playing team sports teaches us virtue. If all that is true, then why do we not encourage all students to play sports?

The Irony: We Do Not Practice As We Preach

Speaking of irony, consider this: What we claim and what we actually do are at odds with one another. We say sports are good for everyone, then we expect coaches to eliminate all but the best athletes from their instruction. Rather than advertising our schools as places where students can get an excellent physical education we expect our coaches to travel far and wide to recruit only the best athletes, i.e. those who need the least instruction and who are most likely to win competitions. It is fairly obvious that, rather than using athletics as a means of inculcating virtue and fostering better thinking, we use athletics to gain honor through victories.

And of course, this is obvious to us. We want to win games because winning is a form of advertising. For good or ill, we accept the fact that high school students will often choose our school in order to participate in the glory of competitions won. But we continue to give the other justifications for participation in athletics, perhaps because we perceive that it would be crass to come right out and say "Come to our college and bask in the glory won by others. It will thrill you, and it might help your job prospects," or "We hope that the victories of our athletes will help us to raise money from people who won't give unless we are winning games."

I don't want to be cynical about this. As I have suggested above and said directly in my previous posts, I'm in favor of athleticism. What troubles me about it is the way that certain college sports become increasingly professionalized. Why, after all, are student athletes considering unionizing? That's something employees do, not students.

Let Everyone Learn To Play

My conclusion is not to push for the elimination of college athletics, but for athletics to be brought more into line with the best reasons for preserving it. If playful exercise makes us better people and better students, then let's urge more students to play. Let's give less attention to inter-collegiate competition and more attention to teaching lifetime sports that will allow our alumni to enjoy the benefits of physical activity for the remainder of their lives. Let's teach poorer students to play golf so that when they enter the business world they aren't at a disadvantage when deals are made on the fairway. Let's teach everyone to swim. Let's take all our students on walks - serious walks, cross-country walks. Let's teach them what Thoreau calls the art of sauntering.

Playful activity takes many forms. We should resist the temptation to think of it as the pursuit of a ball. Swimming, hiking, rock climbing, Tai Chi, dance, yoga, and numerous other activities have the same moral and intellectual benefits as team sports. There should be as many opportunities for vigorous play as there are bodies.

Some of my friends have balked at this, understandably. Not all of us are athletic, or at least not all of us feel athletic. But I think a good deal of this is because many of us learned about athletics in a victory-oriented environment. That environment fosters a narrow and shallow view of the active human life. We may not all be quarterbacks, point guards, shortstops, or strikers, but all of us can be active within the limits of the bodies we have been given. If activity is good for us, then we should treat it as good for all of us. Play should not be limited to the activity of a few for the thrill of the inactive many. Play should be, as Peirce said, "a lively exercise of our powers," whatever those powers may be. And it should be a delight.

∞

Secular Liturgy

Last night I attended the Maundy Thursday service at our church. I admit I'm not a fan of sitting still, of pews in general, or of listening to sermons. I also haven't got any great love for singing with a small congregation that doesn't really like to sing.

But I've found I need liturgy in my life. Liturgies help me mark seasons. More than that, liturgies create seasons. That's what I really need, because the creation of seasons becomes, for me, a discipline of memory.

Liturgies help me to count my days, which in turn helps me to make my days count.

I used to chafe at the remembrance of birthdays. Why should one day count more than any other? And why should one day seem more a holiday than another?

I'm slowly getting it. There is nothing special about the day; what is special is the use of the day. Cheerless debunkers never tire of pointing out to me that western Christmas is celebrated on a Roman holiday, that Easter is *really* some kind of fertility rite because it's celebrated in the springtime, that all my holidays don't mean what I think they mean because someone once celebrated them in another way. As though the genealogy of the holiday should be its only meaning, as though the celebrations of the past should have magical power over me, as though I had no power to make the days mean something new to me.

And it is true: holidays and liturgies do have power. As I have said before, what we cherish in our hearts we worship, and what we worship we come to resemble or imitate. Holidays are always about remembering, and remembering is cherishing. Of course, we don't all cherish the same things. Memorial Day is, for some, a remembrance of valor and sacrifice. For others, it is a good day for a picnic with family. Both are forms of cherishing, though the thing cherished is quite different.

Much of the difference probably comes from mindfulness and intention, or lack of intention. Everyone cherishes something, but not all of us think about what we cherish. Liturgies help me to cherish mindfully.

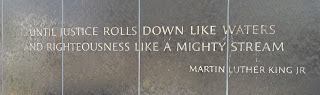

Which is why every April 4th I read or listen to Dr. King's "I Have A Dream" speech, and weep at his loss. And why every July 4th I read the Declaration of Independence. I have set aside days in my year, every year, to read texts like these, texts that have shaped my community. Because these texts aren't done with their shaping. Texts don't hit us once and do all their work; texts seep into us, their words become our words.

Reading and re-reading and reading aloud in communities - these things are like the pouring of water through leaves or grounds - the reading percolates through the words and picks up the essential oils, the savor, the color and taste of the text, and delivers it to us like tea or hot coffee. We taste the words and then the words enter our guts, our veins, our souls.

I recently read an interview with a woman who said "I don't need to go to church to believe those things," referring to her church's beliefs. True. Just as I don't need to go to the gym to get exercise, or to believe that exercise is good for me. But if I don't make a habit of getting exercise, I find I tend not to get what my body needs. The urgent matters in life so easily overwhelm the important ones. Often, when I return from the gym, my wife asks me "How was the gym?" I always think, "It was hard. Everything I do at the gym is difficult." But it is worth doing, because it helps me to maintain my health, and to fight my own decline, to fight the slow slipping away of what I want to hold onto as long as I can. If I do this for my body, why should I not also do it for my heart and mind?

I'm not writing this to endorse all liturgies. I'm confident that there are liturgies that celebrate awful things, and that there are participants in liturgies who make poor use of the liturgies they sit through. As with most of what I write here, I'm trying to sort out what I believe, and why -- as another kind of discipline, one of remembering, and of being mindful of what I believe.

The liturgy of Maundy Thursday is not an easy one, because it reminds me of two things I am capable of: I am capable, like Jesus, of washing others' feet, and of living a life of love; and I am capable, like Jesus' friends, of betraying those people and ideals I most claim to cherish and worship. If my worship is only worship in words, I find it easy to forget to worship what is best with my body, with my life. Liturgies - and we all have liturgies - are the ways I remind my whole person to stop and remember what my words claim so easily to believe.

But I've found I need liturgy in my life. Liturgies help me mark seasons. More than that, liturgies create seasons. That's what I really need, because the creation of seasons becomes, for me, a discipline of memory.

Liturgies help me to count my days, which in turn helps me to make my days count.

I used to chafe at the remembrance of birthdays. Why should one day count more than any other? And why should one day seem more a holiday than another?

I'm slowly getting it. There is nothing special about the day; what is special is the use of the day. Cheerless debunkers never tire of pointing out to me that western Christmas is celebrated on a Roman holiday, that Easter is *really* some kind of fertility rite because it's celebrated in the springtime, that all my holidays don't mean what I think they mean because someone once celebrated them in another way. As though the genealogy of the holiday should be its only meaning, as though the celebrations of the past should have magical power over me, as though I had no power to make the days mean something new to me.

And it is true: holidays and liturgies do have power. As I have said before, what we cherish in our hearts we worship, and what we worship we come to resemble or imitate. Holidays are always about remembering, and remembering is cherishing. Of course, we don't all cherish the same things. Memorial Day is, for some, a remembrance of valor and sacrifice. For others, it is a good day for a picnic with family. Both are forms of cherishing, though the thing cherished is quite different.

Much of the difference probably comes from mindfulness and intention, or lack of intention. Everyone cherishes something, but not all of us think about what we cherish. Liturgies help me to cherish mindfully.

Which is why every April 4th I read or listen to Dr. King's "I Have A Dream" speech, and weep at his loss. And why every July 4th I read the Declaration of Independence. I have set aside days in my year, every year, to read texts like these, texts that have shaped my community. Because these texts aren't done with their shaping. Texts don't hit us once and do all their work; texts seep into us, their words become our words.

Reading and re-reading and reading aloud in communities - these things are like the pouring of water through leaves or grounds - the reading percolates through the words and picks up the essential oils, the savor, the color and taste of the text, and delivers it to us like tea or hot coffee. We taste the words and then the words enter our guts, our veins, our souls.

I recently read an interview with a woman who said "I don't need to go to church to believe those things," referring to her church's beliefs. True. Just as I don't need to go to the gym to get exercise, or to believe that exercise is good for me. But if I don't make a habit of getting exercise, I find I tend not to get what my body needs. The urgent matters in life so easily overwhelm the important ones. Often, when I return from the gym, my wife asks me "How was the gym?" I always think, "It was hard. Everything I do at the gym is difficult." But it is worth doing, because it helps me to maintain my health, and to fight my own decline, to fight the slow slipping away of what I want to hold onto as long as I can. If I do this for my body, why should I not also do it for my heart and mind?

|

| The words percolate through us, and enter our veins. |

I'm not writing this to endorse all liturgies. I'm confident that there are liturgies that celebrate awful things, and that there are participants in liturgies who make poor use of the liturgies they sit through. As with most of what I write here, I'm trying to sort out what I believe, and why -- as another kind of discipline, one of remembering, and of being mindful of what I believe.

The liturgy of Maundy Thursday is not an easy one, because it reminds me of two things I am capable of: I am capable, like Jesus, of washing others' feet, and of living a life of love; and I am capable, like Jesus' friends, of betraying those people and ideals I most claim to cherish and worship. If my worship is only worship in words, I find it easy to forget to worship what is best with my body, with my life. Liturgies - and we all have liturgies - are the ways I remind my whole person to stop and remember what my words claim so easily to believe.