fish

How I Learned To Love Insects

I've just posted this on Medium, with a handful of my favorite insect photos.

| ||

| Crimson Patch Butterfly (chlosyne janais; Costa Rica). |

Insects used to frighten me. Now I love them, and I am more concerned about losing them than living with them.

At the end of the article I've offered some tips about how to ensure we have a happy future together with the insects and other arthropods around us. Enjoy.

(Image copyright 2022 David L. O'Hara)

Watching the Fish

I've been publishing some short pieces on Medium lately. It's a way of doing some quick writing about things I've taught about for years.

This latest one is about watching fish, and I hope you enjoy it. Here's a sample:

I love fish. And whenever I say that, most people assume I love either eating fish or catching them. But neither of those is what I mean.

What I mean, more than anything, is that I love watching them at home in the places where they live.

You can find the whole article here.

Of Fish and Forests

When people ask me what I do I sometimes reply “I study the relationships between fish and forests.”

A more precise way to describe my job might be to say I’m a teacher, a scholar, and a department chair and program director at my university. But that answer is pretty dry and uninteresting.

Adding detail doesn’t always help, though I could say that I teach philosophy, classics, religious studies, theology, field ecology, study abroad, environmental studies, and sustainability; and that I take my students to the places I study: rainforests in the tropics and in Alaska, deserts, and the Mediterranean.

So instead I say “fish and forests.” The words are simple and easy to understand. I hope they invite more questions, and often they do.

|

| Salmon bones on woody plants beside a river near Lake Clark, Alaska. A bear left these bones after a meal. |

The question I hope for is some version of “what do fish have to do with forests?” The short version is: nearly everything.

Nearly as good as that question is when someone points out that fish don’t live in trees. Short version of my reply: that’s not exactly true, and many of my students can tell you the various ways fish do live in trees. Here are a few:

Around the world, the edges between land and water are held together by roots, and in those places, fish find food, shelter, and places to spawn.

A great example of this is mangroves, which are some of the most important ocean nurseries. Thousands of species bear their young and lay their eggs in mangroves. The mangroves provide shelter from predators; they stabilize the soil, protecting land from hurricanes and strong waves, and protecting the sea from too much runoff. Birds, mammals, insects, and reptiles live in the branches. Fish and myriad aquatic invertebrates live among the roots.

|

| A mangrove on an island off the coast of Belize. |

We could add that there are “forests” of kelp and coral underwater, too.

Wherever birds eat fish, those birds also build the soil when they return to the land. Their waste becomes fertilizer for all manner of grasses, forbs, and trees. Visit the rivers of Alaska and you will find shrubs and trees growing on the banks, where seeds found fertile gardens in mounds of bear poop.

When a bear eats salmon and berries, the berry seeds pass through the bear undigested. The bear deposits the seeds in a steaming pile of fecundity. Bears are forest gardeners.

Here in the middle, between the tropics and the Arctic, the

Big Sioux River is entering its quiet winter’s rest. We haven’t had much rain,

and the river is ankle-deep in many places. The fish gather in deep holes that were

sculpted out by fallen trees. When the river claims a tree, that tree doesn’t

simply float away. It becomes food for beavers and decomposing insects. It

creates eddies that dig deep holes on one side and deposit sediment on the

other. Sometimes the tree becomes a new island, and new trees grow up on its

rotting wood and on the debris it collects. Raccoons grab mussels and crayfish,

and eat them in the branches. Mink and otters dine from a similar menu further

down on the bank.

|

| Tree growing on an island in the Big Sioux River. The tree makes habitat for both terrestrial and aquatic life. |

|

| Near the roots, a deep hole has been carved out. Habitat for fish, hunting grounds for raccoons and other mammals. |

|

| A fallen tree has created an island in the Big Sioux River |

Everywhere I go with my students I ask them to pay attention to the water. The fish and the forests alike need it. The forests keep the water cool and clean, and the fish fertilize the trees. Often, when I am teaching in Morocco or Spain or Greece, I ask them to notice the architecture of water, and the way it relates to our values. Religions have rituals of ablution, and ancient temples collect water from their rooftops, letting it flow down ancient marble columns that imitate the tree trunks that once made porticoes, to flow into cisterns. The narrative of the Christian scriptures begins in a forested garden, and ends in a city with a river flowing through it.

My students smile and roll their eyes at hearing me repeat the same question yet again. What do fish have to do with forests? What does water have to do with dry ground?

|

| Traditional Itzá canoes on the shore of Lake Petén Itzá. |

And then one will point out a young mangrove shoot, a migrating salmon, a traditional Itzá canoe on a lakeshore, a baptismal font, a hammam, a public fountain, a Roman aqueduct.

And we will all stop for a moment and consider the way that this water, right here, flows through every part of our lives.

South Fork, Eagle River

The houses here are ugly. Taken on their own, any one of them is a beautiful building. Plainly this is spendy real estate in God’s country. But the houses look like they were lifted from the pages of some little-boxes-full-of-ticky-tacky architectural lust propaganda and carpet-bombed on the hillside, then allowed to remain wherever they fell. There is no order, no sense that the houses were built for the place. Every one of them is a garish, angular excrescence on the opposite hillside. No doubt their inmates would disagree with my assessment; they only see the houses up close, and from the inside. They must have no idea how out of place their unnatural rectangles look against the sweeping slope of the Chugach Range. No doubt, when you’re on the other side of those big plates of glass, gazing over here at the state park over your morning K-cup, the view is precious. But when you’re in the state park, looking back, there is nothing on the opposite hillside to love. Over here, there is only regret that these people believed that you could buy both the land and the landscape.

It’s about three miles’ hike in to first bridge in state park. A fairly easy up-and-down walk. It’s raining. Spitting, really, what they call chipichipi in Guatemala, a constant drizzle. The sky is a palette of cottony grays that have lowered themselves onto the mountaintops. There is a clear line below which the mountains are visible. Above it, clouds roll and shift.

I shiver a little in my heavy raincoat and think about putting on my rain pants, but I know I’ll be too hot if I do. Some of my students are wearing shorts.

At the footbridge we sit and eat our lunches. The university has packed us red delicious apples (a mendacious name), bags of honey Dijon potato chips, and turkey sandwiches with lettuce and onions. It’s not good turkey, but no one cares. This is a lovely place. We have other food in this place.

The river is only fifteen feet wide here, and it is the color of chalk, like diluted Milk of Magnesia. Taking off my shoes, I wade in. Immediately my feet start to ache with cold. Turning over a stone, I look at its underside. The gray water drips off and a tiny larva wriggles to get out of the light. It's too small to identify it, maybe a miniscule stonefly. A huge blue dragonfly cruises over the river, darting past me.

There are lots of wildflowers up here. One of my students is on the ground with her laminated guidebook, puzzling over one specimen. I've been carrying these guides everywhere, but they're only helpful for about seventy-five percent of the common stuff. There's just too much life here to get it all in a book.

The flowers grow in so many colors, so many strategies for getting the scarce pollinators' attention in the brief summer. Yellows, purples, and blues predominate. The guidebook warns me about several of the purples: DO NOT EAT THIS! Some of them are poisonous. So are a few of the yellows. This is a beautiful place, but it's also a harsh place, and life clings to the edge. Poison is one good way not to get eaten, I suppose. Looking up the mountain, the trees give way to shrubs a hundred yards above us. A hundred yards more and there's only grass. Above that, I can only see rock.

Some of these plants have another strategy: rather than avoiding getting eaten, they invite it. Berries are the way some plants make use of animals to carry their seeds to new places. Bear scat, full of seeds, is all along the trails here. Each mound is a nursery where some new plant may grow in the fertile dung.

There is a kind of berry like a blueberry that grows on something that looks like a mix between evergreens and moss, only a few inches high. Some people call it "mossberry," appropriately. Some locals call it a blackberry. Matt tells us they're crowberries, as he gathers a handful. He eats some and then the students tentatively pick and eat some too.

We spend three hours there at the bridge, observing. There's so much to see. Some of us write, some draw, some stare at the peaks that surround us. A few doze off. I get out my watercolors and try to paint the landscape, but I'm quickly frustrated. There are so many greens and grays and blues, and I'm no good at mixing colors. I keep painting anyway. I can at least try to get the shapes right, I think, but I'm wrong about that, too. The mountains are stacked up in layers, and the lines look clean and clear at first, but when I try to focus on them they blur into one another. The hanging glacier at the end of the valley looms over us, silent and white and yet so eloquent. The glaciers are what made all of this, and even though they have retreated, the river runs with their tillage, the plants grow in their finely ground dust, the smooth slopes were ground smooth by millennia of ice.

Upstream, Brenden hooks his first-ever dolly varden. This is his first fish in Alaska. He is positively glowing with delight. He cradles it in his hand and then quickly returns it to the water pausing only to admire this vibrant glacial relic of a char. It too depends on the glacier.

The temperature is constantly shifting as the sun comes in and out of the clouds. Each part of the valley takes its turn being illuminated: the river shines like silver; the mountainside glows bright green and the rocks and bushes above the tree line cast sharp shadows; high in the valley small glaciers are bright ribbons streaking the blue granite. The clouds push the sunlight in ribbons across the valley. When we are suddenly in the light, we are warm.

After a few hours we walk back to the car. No one wants to go. For a while we drive in luminous silence.

Steinbeck on Overfishing

John Steinbeck, The Log From The Sea Of Cortez. (Penguin, 1995, p. 205) Emphasis added. Feel free to substitute the name of any other coastal government for the word "Mexican."

Professors of Trout

Really, this shouldn't be too surprising. Fly-fishing requires us to look attentively, seeing past the surface of the water in order to discern what is happening deeper down. Far more than simply catching fish, fly-fishing is a practice of reading water as though it were a natural text.

Several authors, professors, and fellow-thinkers have been helping me to deepen my literacy in these streams of thought lately. Among them are Kurt Fausch, Douglas Thompson, and David Suchoff.

Fausch is one of the world's authorities on trout biology and ecology. I had the privilege of reading a draft of Fausch's forthcoming book, For The Love Of Rivers, (see the book trailer here) and I highly recommend it. It is a lovely marriage of science and lyrical writing. You'll learn a lot about the life of rivers, written by a remarkable writer who loves them deeply.

Thompson's book, The Quest For The Golden Trout is next on my to-read list, but I've already snuck some glimpses at it and I am eager to get to it. I'll post more about it when I'm done. Meanwhile, check out his webpage.

I discovered Suchoff recently when I saw one of his students fly-fishing for bonefish in Belize. I teach a January-term field ecology course for Augustana College in Guatemala and Belize. One morning I looked out over the intertidal flat and saw a young woman casting a heavy fly in turtle grass on South Water Caye. I ran into her later on shore and she told me about a terrific class Suchoff teaches at Colby College in Maine. He teaches them the literature of fly-fishing, arranges professional instruction, then takes his students fishing in California, and teaches them to write about it. You can find him on Twitter, too.

One of the joys of research is that it gives me the excuse to write to strangers who share my interests and ask them to teach me what they know. My acquaintance with two of these professors is quite new, but already I've learned from them. The third, Fausch, I've known for long enough that he reviewed a draft of my book and kindly pointed out a few errors before I made them permanent in print.

These are, as I've said, just a few of the university professors who study trout. Are you another? I'd love to hear from you if so.

Green Mountain Creek

Matt and I stand thigh-deep in one of the small streams that

tumble down the eastern slopes of the Green Mountains. Many of those

streams, including this one, have carved steep gorges over the

millennia. As the water falls it strips away the sand and loam, leaving

a course choked with jumbled boulders.

Matt and I stand thigh-deep in one of the small streams that

tumble down the eastern slopes of the Green Mountains. Many of those

streams, including this one, have carved steep gorges over the

millennia. As the water falls it strips away the sand and loam, leaving

a course choked with jumbled boulders.Every year a few more trees, undercut by the current, tip over into the stream, where they lodge against the boulders and form temporary dams. As the water flows over those dams it digs deep plunge pools, bubbling and swirling for a few feet, then quickly settling into swift, clear, tea-colored glassy pools. The water slows only long enough to catch its breath before it plunges again, stair-stepping down the mountain, moving the mountain itself downstream one grain of sand at a time.

Beside us, logs carpeted in moss play host to uncounted lives of plants and animals. Trees reach their branches down into the cleft cut by the river, searching for sunlight wherever they can in this steep gorge. Small flies whirl restlessly across our vision. Their blue wings and olive bodies seem an unnecessary and extravagant dash of color on something so small, so ephemeral.

Vermont is named for the greenness of its mountains, or les monts verts as the first French settlers called these ancient hills. One of the rivers nearby is called the Lemon Fair, its name preserving the French sounds in misplaced English words. A sweeping glance would call this place green, but it only takes a moment of slowing down to really look before you see all the rainbow represented here.

Much of the color is underwater, on the scales of the fine-featured trout that fin the current before us. The native brook trout are dappled a vermiculated green above, fading to pale bellies below. Their fins are slashed with bright red and white. The rainbow trout, imported from the west coast, iridesce when a beam of sunlight finds its way down through the leaves and the water. The young brown trout - far from their native Europe - shine like salmon. Under the rocks small tan sculpin harvest tiny invertebrate meals.

Gray stones slide slower than glaciers down the bank, moving imperceptibly and irresistibly toward the sea. On the bank, seven tiny mushrooms stand up, no taller than my thumb, their caps bright orange like yearling efts.

It is a perfect day. We are grateful to receive it, grateful to be here, to stand in these waters as their life flows around us.

*****

|

| My friends Bill and Brian paddle the Concord River, as Thoreau once did. |

“[F]ishers can be natural historians and waterside contemplatives par excellence."

Anecdotally, I find that hunting and fishing have made me less of a carnivore, and increasingly concerned with animal flourishing. (The quote from Stephanie Mills is found in Epicurean Simplicity, published in Washington, Covelo, and London: Island Press/Shearwater Books, 2002 p.125.)

*****

The Other Drones Problem: The Tragedy of the Unexplored Commons

But there is another ethical issue related to UAVs that doesn't have to do with war. Or, if it does, it has to do with a "war against crude nature."

The technologies we invent in wartime don't go away when the conflicts end. Already, UAVs are being deployed for a number of other uses, and we can expect their uses to increase. I'm no flag-waving Luddite here. The things we invent can be put to diverse uses, some helpful and some harmful. But if we care about promoting the helpful uses, we'll need to be intentional about that.

UAVs are a brilliant platform for remote-sensing technologies. They can cover a lot of ground and stay aloft for a long time. Drone aircraft are adding to our ability to conquer unknown spaces. If you've used Google Maps to explore places you've never been before, you know what an aesthetic boost and letdown this can be: it's a boost to see what you've never seen, and at the same time, we find ourselves sharing Aldo Leopold's lament in "The River of the Mother of God": the unknown places are being replaced by maps, and our deep genetic need to explore runs up against the feeling that everything has already been seen. When I lived in Madrid, I tried to make places like the Retiro park my places of natural exploration and solitude, but I couldn't escape the feeling that I was treading where millions of others had already trod.

|

| We have a deep need for exploration, and so we need places that feel unexplored. |

But that is a small worry compared to the bigger issue of the world's oceans and natural resources. For the whole history of our species we have been able to act as though the world contained unlimited resources. Our species is an explorer species. We have "restless genes," as a recent National Geographic article put it.

Gone is the age of Hemingway's Old Man and the Sea. We no longer take to the seas in small craft and fish commercially with handlines. The last century has pushed fishing fleets thousands of miles from the places where they will ultimately bring their catch to market. We can no longer treat the oceans as limitless resources; we are fishing them out, and some species may collapse under the pressure and never come back.

In the race to find the last remaining schools of fish, we are beginning to use UAVs to scour the seas. Where fishermen once looked for birds circling schools of sardines, robot airplanes now skim the waves and do the searching for us.

|

| At the crossroads |

Ethicists and game theorists refer to this as the "tragedy of the commons": if we each only take resources in proportion to what we can use, the resources can be shared indefinitely. But if some of us take more than our share of the "commons" or the resources, they will have a short-term gain at the expense of the long-term gain of everyone.

The STEM fields (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) are brilliant, and wonderful. New technologies give us new access to the world, and they can save and improve lives. But they lack the ability to regulate themselves, which is why as the STEM fields grow, we need the humanities (and their critiques of technology) to grow with them. If we are not careful, new technologies can also permit us to do great harm to our common world - and to ourselves. If fish seems cheap and plentiful, stop to ask where it came from, and whether that source is sustainable. If it's not, vote with your dollars and eat something else.

Do Philosophy Classes Have "Labs"?

When I was preparing to go to grad school I was torn between two choices: Ph.D. in marine/riparian biology, or Ph.D. in philosophy? I love fish, aquatic invertebrates,

(well, most of them, anyway) and the environments they live in. Wouldn't it be great to make freestone streams and tidal pools into my classrooms?

But I also love philosophy. Philosophy has connections to every other discipline; it offers a unique perspective on human activities; and it promotes some of the most interesting and fruitful conversations I know of. (Yes, I admit some professional bias here, and don't begrudge others a similar bias towards what they love.) Philosophy classes take on questions about truth, value, meaning, religion, justice, science, language, reason, history, relationships, and much more. It can be very difficult, but there's usually a huge payoff for the effort you put into it.

Now that I teach philosophy, I often find myself lurking around the biology department at my school, to read their journals, to talk with the professors there (who patiently put up with my presence there), and to eye their labs with envy.

Now, I think bio labs are great places, but it's not the places themselves that I most like. It's rather the idea of the place. Labs are spaces set apart for learning by experience. We have labs for the sciences, and we have labs for the arts as well (though we usually call those "studios"). In the social sciences they use labs for observing human activities, and foreign languages have (or ought to have) labs for practicing language. Writers have workshops, historians have museums and archives, and other disciplines have internships.

Philosophy, unlike all these other disciplines, does not appear to have any labs at all. At least, not at first glance.

Partly this is due to the reflective nature of philosophy: philosophers have often understood our discipline as a step back from experience in order to gain a cool, disinterested view of the world. To some degree, we still think that, but that idea of having a privileged access to reality through the use of the right kind of language, or through a scientific worldview, has fallen under suspicion. Pace Descartes, we don't necessarily understand the world better by turning completely away from it.

Contrary to popular opinion, "philosophy" is not a synonym for "opinion." Nor is it a synonym for "doctrines." Philosophy has grown and changed quite a lot in the last few centuries, which means that is not always easy to define. One thing that is common to all philosophers, however, is that philosophy is an activity. Doing philosophy is not the mere rehearsal of past views, nor is it merely an attempt to present our already established opinions in clearer or more persuasive language.

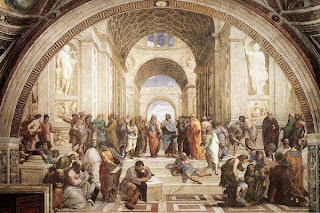

Philosophers do, in fact, set aside spaces and times for practicing philosophy. One important kind of lab philosophers have is the seminar, which has its roots in Plato's practice of philosophy. Whatever else we might say about Plato, he knew how important good conversation is to advancing philosophy. In his dialogues, Plato uses conversation to illustrate two points: first, we need to spend at least some of our time in serious, sustained conversation and reflection with others. Second, when we do so, we need to follow the argument where it leads and not just where we want it to go.

|

| A brook trout I photographed in Maine. |

*********************

[Images: Raphael's "School of Athens," showing famous Greek philosophers "at work"; two mayflies photgraphed in the summer of 2009 in Gravenhurst, Ontario; one of the tributaries to Lake Muskoka in Ontario; a brook trout photographed on the Magalloway River in Maine, 2009 while fishing and doing some research with Matt Dickerson. The Raphael image is in the public domain; the others are my own photos. I think mayflies are especially lovely creatures. The adult stage shown above is a very brief period of their lives; most of their lives are spent underwater, and their appearance is quite different then from what it is as adults.]