forgiveness

Desmond Tutu On Descartes' Radical Individualism

Desmond Tutu, No Future Without Forgiveness, 31. (New York: Random House, 2000)

Pornography and Prayer

"Repetitive viewing of pornography resets neural pathways, creating the need for a type and level of stimulation not satiable in real life. The user is thrilled, then doomed."Thankfully, "doomed" may be an overstatement. As William James and so many others remind us, our habits make us who we are, so we may be able to form new habits to supplant or redirect old ones. I'm no psychologist, but it seems obvious to me that what we hold in front of our consciousness will synechistically affect everything else we think about and do. So it is no surprise that the author of this WSJ article reports that viewing porn may lead to viewing women as things rather than as people.

To put it differently, everyone worships something, and what we worship changes us. This is one of the good reasons to engage in prayer and worship that are intentional. (On a related note, it's a good reason to forgive, too: forgiveness keeps us from internalizing the pain others have caused us, where it can fester and devour us from within.)

(If you read my writing with any regularity you will recognize these as themes I frequently return to. If you're interested, I've written more here and here.)

One of the problems of philosophy of religion has been to try to identify that which certainly deserves our worship. This quest for certainty has often (in my view) distracted us from the more important work of liturgy, wherein we acknowledge our limitations, including our uncertainty. A good liturgy involves worshiping what we believe to be worth worshiping, while acknowledging our own limitations. After all, if worship doesn't include humility on the part of the worshiper, it is probably self-worship.

Another way of putting this is in terms of love. Charles Peirce wrote about this more than a century ago. There are many forms of worship, many kinds of prayer. Without intending to demean the prayer and worship of others, Peirce nevertheless offers what seems to him to be worth our attention: agape love, the love that seeks to nurture others:

"Man's highest developments are social; and religion, though it begins in a seminal individual inspiration, only comes to full flower in a great church coextensive with a civilization. This is true of every religion, but supereminently so of the religion of love. Its ideal is that the whole world shall be united in the bond of a common love of God accomplished by each man's loving his neighbour. Without a church, the religion of love can have but a rudimentary existence; and a narrow, little exclusive church is almost worse than none. A great catholic church is wanted." (Peirce, Collected Papers, 6.442-443)Notice that Peirce uses a small "c" in "catholic." He wasn't trying to proselytize for one sect; quite the opposite. He was trying to proclaim the importance of a church - that is, of a community that shares a commitment to communal worship - of nurturing love.

I am not trying to moralize about pornography. In fact, I see some good in pornography, just as I recognize goodness in the aromas coming from a kitchen where good cooking happens. Pornography probably speaks to some of our most basic desires and needs, for intimacy, affection, attention, and love, as well as our simple, animal longings.

Still, like aromas from a fine kitchen, porn stimulates us without nourishing us. And by giving it too much attention we may be training ourselves to scorn good nutrition. The WSJ article suggests giving up the stimulation as a means of getting over it. I think this is incomplete without a redirection of the attention to what does in fact nourish us. Prayer and worship that refocus our conscious minds on what really merits our attention can prepare us to receive - and to give - good nutrition. That is, by shifting some of our attention from cherishing need-love to cherishing gift-love - from the love that uses others to the love that seeks their flourishing - we might make ourselves into the kind of great lovers our world most needs.

Don't Worship The Monsters

"Killing the bodies of our enemies does not make them disappear. We must also choose to forgive them, in a refusal to let their violence rule our hearts. The alternative is to cherish their violence, silently fondling it in our minds and enshrining it in policies founded on fear."Last Advent I tried to say something similar, in a poem.

All Your Deeds

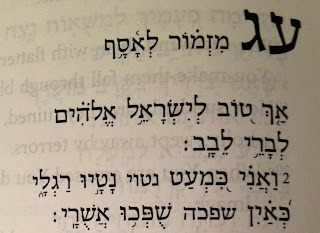

The last line caused me some trouble, though. In it Asaph, the psalmist, says "I will tell of all your [God's] deeds."

Okay, what exactly are those deeds? What can we ever reliably say about God's deeds? If God had done something in history that were not open to historical doubt, there would be no atheists.

The tradition gives us stories about God, and a century of biblical criticism calls those stories myths. Still, as I have argued elsewhere (here, and here, for example) myth is not - or should not be taken as - a synonym for falsehood. Stories may be myths and true, even if not historically true.

As Howard Wettstein argues in his Significance of Religious Experience,

The Bible’s characteristic mode of ‘theology’ is story telling, the stories overlaid with poetic language. Never does one find the sort of conceptually refined doctrinal propositions characteristic of a doctrinal approach. When the divine protagonist comes into view, we are not told much about his properties. Think about the divine perfections, the highly abstract omni-properties (omnipotence, omniscience, and the like), so dominant in medieval and post-medieval theology. One has to work very hard—too hard—to find even hints of these in the Biblical text. Instead of properties, perfection and the like the Bible speaks of God’s roles—father, king, friend, lover, judge, creator, and the like. Roles, as opposed to properties; this should give one pause. (108, emphasis added)The stories may not be about historical "deeds" but may be about the character, the roles of God.

Which makes me wonder: what roles does God play in my life? What "deeds" may I speak of?

|

| The preface to the complaint in Psalm 73 |

Before I reply, let me hasten to say this: I am often reluctant to write too strongly about this sort of thing because I do not want to say that others must believe what I believe. If God has led me to belief, (grant me that for the sake of argument for a moment) God has not strong-armed me into belief but allowed me to arrive at my beliefs over time, letting them be shaped by experience. I do not see why I should allow you less liberty than God has allowed me.

So I write the following admitting that I do not know what I am writing about. As Augustine confessed, when I speak of my love for God, I do so simultaneously wondering what I mean by "God." What can I compare God to? What is God like? I do not know how to answer those questions, except by telling stories, expositing roles. So here goes:

When I was a child, belief in God motivated a family in my neighborhood to care about me and to welcome me into their home when my family was falling apart. Without that love...I shudder to think what I would be today.

God gives me a name for what I pray to. God gives me a focal point for my attention in the vast cosmos, and God gives me a sense that in such a cosmos persons matter. And because persons matter, justice matters. This is not to say one cannot be just without belief, or that belief makes one just - far from it! - only that I find for myself the two ideas closely bound together.

God gives me solace in my mourning and hope when I pray. My mother is dead, but when I speak to God about her, she is not lost.

God gives me a story about the centrality of nurturing love. A reason to think all things are related. Someone to thank. Someone to be angry with. Rest for my soul. Quietness, and in it, trust.

God gives me a story about giving, and why giving and receiving should matter so much.

A story about why, and how, to turn a guilty conscience into repentance. A reason to forgive, and, very often, the strength to forgive. And to hope that I too am forgivable.

A reason to hope that no one is beyond redemption, beyond all hope, completely unworthy of love.

Belief that every person matters. More than that, belief that a teenage girl could be a vessel of the divine; that a third-world martyred prophet could save the world; that an inarticulate foreigner could be a world-historical lawgiver; that a persecuting zealot could get hit so hard by grace that he lives the rest of his life to preach good news for all people everywhere.

Hope that prison doors could be opened, that tongues could be loosed, that great art and great music might be signs of the divine.

I could be wrong about all of this, I know. I know there are other explanations of what I have written above. I also know those explanations apply to music, too, and I'm not interested in hearing about them there either if the reason for offering them is to help disabuse me of my love for good music. I know that people use the same word I use here to justify violence, self-interest, and hatred. I cannot help but feel angry and disgusted when it is used for those ends, ends which seem so contrary to what the word means for me, ends that make me think someone has read the wrong script, mis-cast the character, not known what deeds God has done.

Prayer and Forgiveness

I told a friend about it, who listened patiently to my story. When I was done, he said, sympathetically, "You need to pray for him and ask God to bless him."

What I had hoped to hear was something more like "Wow, what a waste of skin that guy is. Your anger is justified."

Now that I have the increasing clarity that comes when time separates us from painful events, I think my friend was right. His idea of God is that God wants all of us to be better than we are.

Praying for my former co-worker has allowed me to remove him from the center of my consciousness, where his image lived as a threatening villain, and to think of him as someone in need of healing and transformation. Blessing him has given me a way to articulate my desire to see him change and become a kinder person, for everyone's sake.

No doubt theology matters here. In plainer terms, how we imagine the God we pray to matters, because that will shape the way we act towards others. At the risk of declaring the obvious: what we think about God has consequences for the way we live with other people. In her book, Lit, Mary Karr talks about a friend who tells her that God doesn't have a plan for her, God has a dream for her. God wants good things for her.

That's an attractive idea of God, one who wants us to forgive others so we can be set free from their tyranny; and one who wants us to bless others so that we can begin to see ourselves as agents of positive change rather than as victims.

Peirce's Parable of the Puritan

On judgment day, a Puritan was called before God to give account of his life. The Puritan admitted his faults, and then pulled from his breast pocket a document that he claimed contained a justification of "hard-heartedness." When he handed this to God, someone laughed aloud at the possibility of making such a justification. The scoffer was seized by angels and taken to kneel before God, where "he will be told by the Judge that He considered it worthwhile to see what the Puritan had to say. But that he the scoffer as he judged shall be judged."

How can you know that someone is contrite?

For the last few weeks my ethics students have been studying forgiveness. One of the persistent questions about forgiveness is whether, in order to be forgiven, one must first be contrite or repentant. (We have not been speaking of the idea of God forgiving people; we’ve limited our discussion to the possibility of people forgiving other people.)

I have to confess that this posting was prompted as much by my viewing, last night, of Battlestar Galactica as by our readings. In season 3, Laura Roslin calls for a Truth and Reconciliation Commission (like South Africa’s after Apartheid) after some human-on-human atrocities. That got me thinking once again about Desmond Tutu and Simon Wiesenthal, and their respective books on forgiveness.

The easy answer to my question is to say that one does not need to be contrite to be forgiven. This is easy, but not simple, because it raises other questions about the nature of forgiveness. And it brings along with it the possibility of depriving someone of their moral agency by denying the reality of their choices.

Most of us are inclined to give the opposite answer, namely that it does not make sense to forgive those who are not sorry for their offenses.

But this raises another difficulty: how do we know when people are adequately sorry? Additionally, does this position make it more likely that we will forgive those people who only seem sorry? What if someone has expressed their contrition to the best of their ability but we have not been able to perceive it, for cultural or other reasons? What if someone is not at all sorry, but has made a convincing public show of contrition?

What do you think?

Desmond Tutu and The Most Subversive Thing Around

“We were inspired not by political motives. No, we were fired by our biblical faith. The Bible turned out to be the most subversive thing around in a situation of injustice and oppression. We were involved in the struggle because we were being religious, not political. It was because we were obeying the imperatives of our faith.” (No Future Without Forgiveness, 93)

Tutu is making a peculiar claim here, and I can’t entirely tell if he’s serious. He says they weren’t motivated by politics, but by the Bible; but then he says the Bible was subversive. Does he mean that it was politically subversive, or is he talking about some other kind of subversion - spiritual or moral or psychological subversion, perhaps? I guess the question is this: what exactly was being subverted? He says plainly that it was “injustice and oppression.” But what is not so plain is whether the injustice and oppression were primarily political; or if the political was only a sign or symptom of something else.

I've also been reading a lot of William James this week, especially The Varieties of Religious Experience. James argues that we should not judge religion a priori but rather a posteriori. As James puts it, "not by its roots, but by its fruits."

In that book and elsewhere, James argues that we are wrong to think that reason's chief role in religious experience is to judge the truth-claims of religion. Rather, religion is to be understood as playing a role within reason itself. Religion "is something more, namely, a postulator of new facts as well" as being a means of "illumination of facts already elsewhere given."

James and Tutu both offer religion as more than simply another second-string player on an already deep bench, and as more than a degenerate form of political reasoning. For both of them, religion is a source of insight that cannot be had in other ways.