Friluftsliv

- This too is related to technology, of course. If the class is focused on video screens, then all the chairs will face the screens, and the classroom might even be structured like a theater. Etymologically, "theater" means something like "a place of gazing," and theaters tend to encourage people to gaze. Sometimes this can work against other activities, like colloquy, small-group interaction, and really anything that involves students moving from one place to another.

- If that last sentence made you ask,"But why do you want your students to move from one place to another?" then you see that we have some pretty strong presuppositions about how education should happen: students should sit and listen, teachers should stand and lecture. This communicates something about authority, and at times that's helpful. But it can also invite students to lean back into passivity, and to assume they have no role in their own education.

- The furniture in classrooms tells us how people are to behave, because it has been made and purchased by people who had in mind some idea of how students should behave. Most wrap-around desks are made for right-handed people, for instance. And most classroom desks I've seen expect students to sit upright, at attention, with a book open in front of them. I really don't like those desks, and I feel trapped when I sit in them. I wonder sometimes how they make my students feel. I wish we had fewer chairs and more sofas. Maybe a fireplace, or some tables with glasses of water, and ashtrays on them. I suppose I wish I could teach in pubs or ratskellers, which are, after all, places consciously designed for people to meet and discuss what most matters to them, informally, passionately, amicably.

- Classrooms that privilege video screens tend to undervalue natural light and windows. I am reminded of Emerson's reflection on a boring sermon he once heard. Emerson wrote, in his Divinity School Address, that while the minister droned on, Emerson looked out the window at the falling snow, which, he proclaimed, preached a better sermon than the minister. I have no doubt that nature can often give a better lecture than I can.

∞

The Trace I Left Behind

This summer I spent several weeks in and around Lake Clark National Park doing research on trout, salmon, and char.

Sometimes I get quizzical looks when I say that I, a philosophy and classics professor, am researching fish. Let me explain.

I teach environmental philosophy and a range of classes in what I call "environmental humanities." These include courses in environmental ethics, nature writing, philosophy of nature, and even a course on environmental law and policy for first-year undergraduates, as an introduction to being a university student.

I also teach courses in field ecology, including a monthlong course in tropical ecology in Guatemala and Belize. I teach in Greece over my spring break, and this year we will be looking at the expansion of fish farms in the Mediterranean and how fishing has changed there over the last six thousand years.

Closer to home, I teach and practice what Norwegians call friluftsliv, or life in the free air. Whenever possible, I teach outdoors. Most years, I take my ancient philosophy students camping in the Badlands National Park to watch the Orionid meteor shower while we lie on sleeping bags under the stars.

In all of this, my aim is to make sure that nature is not an abstraction to my students, nor to me. I want to know the places the fish live, the grasslands the bison roam, the forests where the jaguar and the ocelot hunt, the tundra rivers where the Dolly Varden chase the salmon under the watchful gaze of the bears.

In other words, my aim is to stay in contact with wildness, and to do so in a way that allows me to take something valuable home: intimate knowledge. I am not a scientist, so I don't bring samples back to a laboratory. I do bring home photographs, and I do spend a lot of time making observations of the places I work, so that I can bring home notebooks full of writing to share with my students. And of course, I write books and articles to share with others.

This summer, I was sorely tempted to bring something else home from Lake Clark: a tiny fossil. I had chartered a float plane to take me to a fairly remote lake, and there my fellow researchers and I walked the shore to the mouth of a stream full of spawning salmon and rainbow trout.

As I often do, I sat down on the gravel and started to turn over rocks to see what invertebrates were living there. The salmon are bright red and eye-catching, but the bugs and spiders tell an important part of the story of a place, as Kurt Fausch has written about in his recent book, For The Love Of Rivers. Who was it - J.B.S. Haldane, perhaps? - who quipped that God has "an inordinate fondness for beetles." The world is full of wonderful, tiny lives that are easy to overlook.

I don't try to bring beetles home, but one insect tempted me this summer. Really, it was just a trace of an insect, just the trace of its wings, in fact. I can't even tell you what insect it was. All I can tell you is that somewhere near that river, probably millions of years ago, something like a dragonfly died in the mud, and the river graced its delicate wings with the cerement of silt. That silt took the form of the wings, those wings left a fingerprint - a wingprint - on the earth. And this summer, I found that print, that delicate, wonderful trace.

While my son and my friend and our pilot walked, I sat with that stone in my hand and thought about pocketing it. Here I was in the wilderness, and no one would know. It's one tiny stone in the largest state in the union; who would miss it?

Ah, but it is one tiny stone that does not belong to me. It is one tiny stone in a vast wilderness that belongs to all of us, and to all who will come after us. It is one tiny piece of rock with an incomplete fossil of a little odonata. The river there has held it and cared for it since time immemorial.

Now I am back in South Dakota, but a tiny trace of my heart remains along the strand of that stream in Alaska. It lies there, wrapped around that delicate trace of insect wing, and I will never find it again in that vast wilderness.

But perhaps someone else will. Until then, perhaps it is best not to let Midas' longings turn our hearts to stone too soon. Let's walk the shores together, I will continue to say to my students. And let's bring something intangible home in our memories. And let's do the hard work of leaving behind the beautiful, delicate traces that wildness has safeguarded for so many, many years.

Sometimes I get quizzical looks when I say that I, a philosophy and classics professor, am researching fish. Let me explain.

I teach environmental philosophy and a range of classes in what I call "environmental humanities." These include courses in environmental ethics, nature writing, philosophy of nature, and even a course on environmental law and policy for first-year undergraduates, as an introduction to being a university student.

I also teach courses in field ecology, including a monthlong course in tropical ecology in Guatemala and Belize. I teach in Greece over my spring break, and this year we will be looking at the expansion of fish farms in the Mediterranean and how fishing has changed there over the last six thousand years.

Closer to home, I teach and practice what Norwegians call friluftsliv, or life in the free air. Whenever possible, I teach outdoors. Most years, I take my ancient philosophy students camping in the Badlands National Park to watch the Orionid meteor shower while we lie on sleeping bags under the stars.

In all of this, my aim is to make sure that nature is not an abstraction to my students, nor to me. I want to know the places the fish live, the grasslands the bison roam, the forests where the jaguar and the ocelot hunt, the tundra rivers where the Dolly Varden chase the salmon under the watchful gaze of the bears.

In other words, my aim is to stay in contact with wildness, and to do so in a way that allows me to take something valuable home: intimate knowledge. I am not a scientist, so I don't bring samples back to a laboratory. I do bring home photographs, and I do spend a lot of time making observations of the places I work, so that I can bring home notebooks full of writing to share with my students. And of course, I write books and articles to share with others.

This summer, I was sorely tempted to bring something else home from Lake Clark: a tiny fossil. I had chartered a float plane to take me to a fairly remote lake, and there my fellow researchers and I walked the shore to the mouth of a stream full of spawning salmon and rainbow trout.

|

| Salmon preparing to spawn |

As I often do, I sat down on the gravel and started to turn over rocks to see what invertebrates were living there. The salmon are bright red and eye-catching, but the bugs and spiders tell an important part of the story of a place, as Kurt Fausch has written about in his recent book, For The Love Of Rivers. Who was it - J.B.S. Haldane, perhaps? - who quipped that God has "an inordinate fondness for beetles." The world is full of wonderful, tiny lives that are easy to overlook.

I don't try to bring beetles home, but one insect tempted me this summer. Really, it was just a trace of an insect, just the trace of its wings, in fact. I can't even tell you what insect it was. All I can tell you is that somewhere near that river, probably millions of years ago, something like a dragonfly died in the mud, and the river graced its delicate wings with the cerement of silt. That silt took the form of the wings, those wings left a fingerprint - a wingprint - on the earth. And this summer, I found that print, that delicate, wonderful trace.

|

| Fossilized trace of an insect's wing |

While my son and my friend and our pilot walked, I sat with that stone in my hand and thought about pocketing it. Here I was in the wilderness, and no one would know. It's one tiny stone in the largest state in the union; who would miss it?

Ah, but it is one tiny stone that does not belong to me. It is one tiny stone in a vast wilderness that belongs to all of us, and to all who will come after us. It is one tiny piece of rock with an incomplete fossil of a little odonata. The river there has held it and cared for it since time immemorial.

Now I am back in South Dakota, but a tiny trace of my heart remains along the strand of that stream in Alaska. It lies there, wrapped around that delicate trace of insect wing, and I will never find it again in that vast wilderness.

But perhaps someone else will. Until then, perhaps it is best not to let Midas' longings turn our hearts to stone too soon. Let's walk the shores together, I will continue to say to my students. And let's bring something intangible home in our memories. And let's do the hard work of leaving behind the beautiful, delicate traces that wildness has safeguarded for so many, many years.

∞

Camping With My Students: Stargazing in the Badlands

Around two in the morning I awoke to the song of coyotes. I opened my eyes and looked up just in time to see a green meteor arc across the sky. I was camping outdoors, with my students, in a remote corner of South Dakota. Welcome to one of my favorite classrooms.

Each fall I look for an ideal weekend to take my Ancient and Medieval Philosophy students stargazing. An ideal weekend counts as one where we will have clear skies, a new moon, and reasonably warm weather so we can spend a lot of time outside.

Several times over the last ten years, the weather's been so good that we've been able to go out to a primitive campground (i.e. one where there is no electricity and almost no urban glow) in the Badlands National Park.

On such nights, in such places, the sky glistens with stars. The Milky Way is a bright band across the night, and meteors punctuate our views each hour.

I tell my students that this is an optional trip. They don't get credit for coming, and they don't lose any credit for staying home. It's a four-hour drive from our campus, so it's a real commitment of time on their part. Their only rewards are these: an experience of what the Norwegians call friluftsliv, a beautiful night under the stars in a remote and lovely place, and free pancakes at sunrise, cooked by me.

And yet every time I offer this trip, half a dozen or more students - and sometimes other professors - tag along.

I've written before about the importance of teaching outdoors and of doing labs in philosophy. Experientia docet, experience teaches us. What we learn through lived, full-bodied experience tends to stick with us far better than what we simply hear spoken from a lectern or see on a PowerPoint slide.

We go out there, ostensibly, to see the stars. This is because I want my students to watch the skies and to imagine what it would have been like for ancient and medieval philosophers like Thales, Plutarch, Ptolemy, Eratosthenes and, even Galileo (on the cusp of the Middle Ages) to gaze at the skies and learn from their movements.

But we are really there for other reasons that are easier to show than to tell. I want them to see that ideas do not grow up in a vacuum, and that the artificial divisions between academic disciplines are really artificial and convenient. Educated people should care about all the disciplines. We should not allow them to be compartmentalized, as though philosophy and sociology had nothing to do with accounting, or physics, or poetry.

Aristotle tells us that the love of wisdom begins in wonder. I will add that experience of new things can be the beginning of wonder.

Many of my students have never heard coyotes sing. In the Badlands, they trot past our cots and tents and sing to us all night long. When we wake in the morning, we are often surrounded by small groups of bison, slowly grazing their way along the hillsides. After breakfast we climb the steep slopes and find ancient fossils.

I don't know if any of this is a desirable or assessable outcome for a philosophy class. Also, I don't care. Because all of these things are, I think, desirable outcomes for life.

Because I believe that "it is beautiful to do so" is reason enough to sleep under the stars.

|

| We set up tents, but we rarely use them. Much nicer to sleep under the stars. |

Each fall I look for an ideal weekend to take my Ancient and Medieval Philosophy students stargazing. An ideal weekend counts as one where we will have clear skies, a new moon, and reasonably warm weather so we can spend a lot of time outside.

Several times over the last ten years, the weather's been so good that we've been able to go out to a primitive campground (i.e. one where there is no electricity and almost no urban glow) in the Badlands National Park.

On such nights, in such places, the sky glistens with stars. The Milky Way is a bright band across the night, and meteors punctuate our views each hour.

I tell my students that this is an optional trip. They don't get credit for coming, and they don't lose any credit for staying home. It's a four-hour drive from our campus, so it's a real commitment of time on their part. Their only rewards are these: an experience of what the Norwegians call friluftsliv, a beautiful night under the stars in a remote and lovely place, and free pancakes at sunrise, cooked by me.

And yet every time I offer this trip, half a dozen or more students - and sometimes other professors - tag along.

|

| The stop sign is just a scratching post to this bison. |

I've written before about the importance of teaching outdoors and of doing labs in philosophy. Experientia docet, experience teaches us. What we learn through lived, full-bodied experience tends to stick with us far better than what we simply hear spoken from a lectern or see on a PowerPoint slide.

We go out there, ostensibly, to see the stars. This is because I want my students to watch the skies and to imagine what it would have been like for ancient and medieval philosophers like Thales, Plutarch, Ptolemy, Eratosthenes and, even Galileo (on the cusp of the Middle Ages) to gaze at the skies and learn from their movements.

But we are really there for other reasons that are easier to show than to tell. I want them to see that ideas do not grow up in a vacuum, and that the artificial divisions between academic disciplines are really artificial and convenient. Educated people should care about all the disciplines. We should not allow them to be compartmentalized, as though philosophy and sociology had nothing to do with accounting, or physics, or poetry.

Aristotle tells us that the love of wisdom begins in wonder. I will add that experience of new things can be the beginning of wonder.

Many of my students have never heard coyotes sing. In the Badlands, they trot past our cots and tents and sing to us all night long. When we wake in the morning, we are often surrounded by small groups of bison, slowly grazing their way along the hillsides. After breakfast we climb the steep slopes and find ancient fossils.

I don't know if any of this is a desirable or assessable outcome for a philosophy class. Also, I don't care. Because all of these things are, I think, desirable outcomes for life.

Because I believe that "it is beautiful to do so" is reason enough to sleep under the stars.

∞

As September approaches, people keep asking me, "Are you ready to get back in the classroom?"

As early as middle school I knew I wanted to become a college professor, and I love my job. It is a delight to spend time with young people who are curious, after all.

Years ago, my friend Matt Dickerson pointed out to me that it's also my job to help those who are not curious to see why they should be. As it turns out, that work is usually delightful, too, a rewarding challenge.

So on the whole, I love my work.

But I admit I don't love classrooms, for several reasons:

First, no matter what decade, every classroom I've been in has exhibited an unhealthy tendency towards becoming cluttered with the latest technology, and most of that tech seems to take up a lot of space and to become the center of attention. I'm not opposed to technology in the classroom, not at all. But I'm opposed to letting it get in the way, as it does when the "Smart Cart" leaves me no room for my lecture notes, or when I can't seem to turn the ceiling-mounted projector on or off. I'm a fan of chalk, because chalk allows spontaneity, and it allows for much more than alphanumeric writing in neat rows. Sadly, concerns about chalk dust getting into computers is threatening to make chalkboards disappear from my classrooms. Alas. Chalk is an excellent technology, and if it vanishes, I will mourn its loss.

Second, classroom architecture is not some value-free, neutral design. Classroom architecture makes a big difference in how people teach, and how they learn:

Which is why, as often as I can, I get my students out of the classroom. When we are reading Thoreau's Walking, we go for a walk. When I teach environmental philosophy, we often meet under the great tree in our campus quad, where I encourage students to daydream and to play with the grass, to look for worm-castings and owl pellets, feathers and seed-pods, invertebrates and fallen bits of bark. What good is it to gain the world of theoretical knowledge at the expense of knowledge gained through vital, haptic, bodily experience?

And this is why I am a preacher of the importance of study abroad. Not just travel, but serious, engaged, rigorous study in the classroom of life in another place. This is why I teach Classics in Greece every year, and why year after year I take students to Central America to study environmental philosophy and ecology.

More and more I've been trying to shift the learning focus in my classes from the classroom to the laboratory - where by "laboratory" I mean anywhere that allows students to learn with their whole person. I make my ancient philosophy students devote hours each semester to star-gazing, in part because this is what the ancients did, and in part because I don't want them to miss the stars. I want them to gaze in wonder at the firmament so that when they read Aristotle and Galileo they know that they've looked at what those great minds saw as well. We even occasionally take field trips to really dark places like the South Dakota Badlands so we can see the skies even better.

My environmental philosophy students must observe a square meter of earth for a semester, spending an hour at a time without a camera, drawing and writing about what they see, because it does not make sense to me to talk about the earth when you have not taken the time to sit upon it, to listen to it, to smell and taste it, and to see what other lives creep, and walk, and fly across it.

My friend Aage Jensen advocates the Norwegian philosophy of Friluftsliv, life and education outdoors. And when he organizes a conference on it, he eschews conference centers and holds the conference while walking through the mountains, or paddling a river. Because he believes that one should practice what one preaches, and that nature is always ready to teach.

To paraphrase the Stoic Musonius, teachers would do well to talk less and to take their students with them into the fields, because there they will learn far better and far more than in the lecture hall.

Teaching Outdoors

|

As early as middle school I knew I wanted to become a college professor, and I love my job. It is a delight to spend time with young people who are curious, after all.

Years ago, my friend Matt Dickerson pointed out to me that it's also my job to help those who are not curious to see why they should be. As it turns out, that work is usually delightful, too, a rewarding challenge.

So on the whole, I love my work.

But I admit I don't love classrooms, for several reasons:

First, no matter what decade, every classroom I've been in has exhibited an unhealthy tendency towards becoming cluttered with the latest technology, and most of that tech seems to take up a lot of space and to become the center of attention. I'm not opposed to technology in the classroom, not at all. But I'm opposed to letting it get in the way, as it does when the "Smart Cart" leaves me no room for my lecture notes, or when I can't seem to turn the ceiling-mounted projector on or off. I'm a fan of chalk, because chalk allows spontaneity, and it allows for much more than alphanumeric writing in neat rows. Sadly, concerns about chalk dust getting into computers is threatening to make chalkboards disappear from my classrooms. Alas. Chalk is an excellent technology, and if it vanishes, I will mourn its loss.

Second, classroom architecture is not some value-free, neutral design. Classroom architecture makes a big difference in how people teach, and how they learn:

|

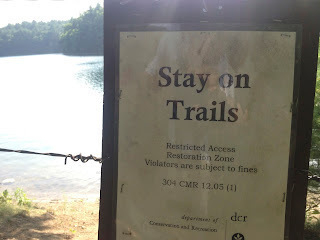

| Step off the trails! Explore! An ironic sign at Walden Pond. |

And this is why I am a preacher of the importance of study abroad. Not just travel, but serious, engaged, rigorous study in the classroom of life in another place. This is why I teach Classics in Greece every year, and why year after year I take students to Central America to study environmental philosophy and ecology.

More and more I've been trying to shift the learning focus in my classes from the classroom to the laboratory - where by "laboratory" I mean anywhere that allows students to learn with their whole person. I make my ancient philosophy students devote hours each semester to star-gazing, in part because this is what the ancients did, and in part because I don't want them to miss the stars. I want them to gaze in wonder at the firmament so that when they read Aristotle and Galileo they know that they've looked at what those great minds saw as well. We even occasionally take field trips to really dark places like the South Dakota Badlands so we can see the skies even better.

My environmental philosophy students must observe a square meter of earth for a semester, spending an hour at a time without a camera, drawing and writing about what they see, because it does not make sense to me to talk about the earth when you have not taken the time to sit upon it, to listen to it, to smell and taste it, and to see what other lives creep, and walk, and fly across it.

My friend Aage Jensen advocates the Norwegian philosophy of Friluftsliv, life and education outdoors. And when he organizes a conference on it, he eschews conference centers and holds the conference while walking through the mountains, or paddling a river. Because he believes that one should practice what one preaches, and that nature is always ready to teach.

To paraphrase the Stoic Musonius, teachers would do well to talk less and to take their students with them into the fields, because there they will learn far better and far more than in the lecture hall.

|

| Nature is full of things worth seeing. |