Galileo

- This too is related to technology, of course. If the class is focused on video screens, then all the chairs will face the screens, and the classroom might even be structured like a theater. Etymologically, "theater" means something like "a place of gazing," and theaters tend to encourage people to gaze. Sometimes this can work against other activities, like colloquy, small-group interaction, and really anything that involves students moving from one place to another.

- If that last sentence made you ask,"But why do you want your students to move from one place to another?" then you see that we have some pretty strong presuppositions about how education should happen: students should sit and listen, teachers should stand and lecture. This communicates something about authority, and at times that's helpful. But it can also invite students to lean back into passivity, and to assume they have no role in their own education.

- The furniture in classrooms tells us how people are to behave, because it has been made and purchased by people who had in mind some idea of how students should behave. Most wrap-around desks are made for right-handed people, for instance. And most classroom desks I've seen expect students to sit upright, at attention, with a book open in front of them. I really don't like those desks, and I feel trapped when I sit in them. I wonder sometimes how they make my students feel. I wish we had fewer chairs and more sofas. Maybe a fireplace, or some tables with glasses of water, and ashtrays on them. I suppose I wish I could teach in pubs or ratskellers, which are, after all, places consciously designed for people to meet and discuss what most matters to them, informally, passionately, amicably.

- Classrooms that privilege video screens tend to undervalue natural light and windows. I am reminded of Emerson's reflection on a boring sermon he once heard. Emerson wrote, in his Divinity School Address, that while the minister droned on, Emerson looked out the window at the falling snow, which, he proclaimed, preached a better sermon than the minister. I have no doubt that nature can often give a better lecture than I can.

∞

As September approaches, people keep asking me, "Are you ready to get back in the classroom?"

As early as middle school I knew I wanted to become a college professor, and I love my job. It is a delight to spend time with young people who are curious, after all.

Years ago, my friend Matt Dickerson pointed out to me that it's also my job to help those who are not curious to see why they should be. As it turns out, that work is usually delightful, too, a rewarding challenge.

So on the whole, I love my work.

But I admit I don't love classrooms, for several reasons:

First, no matter what decade, every classroom I've been in has exhibited an unhealthy tendency towards becoming cluttered with the latest technology, and most of that tech seems to take up a lot of space and to become the center of attention. I'm not opposed to technology in the classroom, not at all. But I'm opposed to letting it get in the way, as it does when the "Smart Cart" leaves me no room for my lecture notes, or when I can't seem to turn the ceiling-mounted projector on or off. I'm a fan of chalk, because chalk allows spontaneity, and it allows for much more than alphanumeric writing in neat rows. Sadly, concerns about chalk dust getting into computers is threatening to make chalkboards disappear from my classrooms. Alas. Chalk is an excellent technology, and if it vanishes, I will mourn its loss.

Second, classroom architecture is not some value-free, neutral design. Classroom architecture makes a big difference in how people teach, and how they learn:

Which is why, as often as I can, I get my students out of the classroom. When we are reading Thoreau's Walking, we go for a walk. When I teach environmental philosophy, we often meet under the great tree in our campus quad, where I encourage students to daydream and to play with the grass, to look for worm-castings and owl pellets, feathers and seed-pods, invertebrates and fallen bits of bark. What good is it to gain the world of theoretical knowledge at the expense of knowledge gained through vital, haptic, bodily experience?

And this is why I am a preacher of the importance of study abroad. Not just travel, but serious, engaged, rigorous study in the classroom of life in another place. This is why I teach Classics in Greece every year, and why year after year I take students to Central America to study environmental philosophy and ecology.

More and more I've been trying to shift the learning focus in my classes from the classroom to the laboratory - where by "laboratory" I mean anywhere that allows students to learn with their whole person. I make my ancient philosophy students devote hours each semester to star-gazing, in part because this is what the ancients did, and in part because I don't want them to miss the stars. I want them to gaze in wonder at the firmament so that when they read Aristotle and Galileo they know that they've looked at what those great minds saw as well. We even occasionally take field trips to really dark places like the South Dakota Badlands so we can see the skies even better.

My environmental philosophy students must observe a square meter of earth for a semester, spending an hour at a time without a camera, drawing and writing about what they see, because it does not make sense to me to talk about the earth when you have not taken the time to sit upon it, to listen to it, to smell and taste it, and to see what other lives creep, and walk, and fly across it.

My friend Aage Jensen advocates the Norwegian philosophy of Friluftsliv, life and education outdoors. And when he organizes a conference on it, he eschews conference centers and holds the conference while walking through the mountains, or paddling a river. Because he believes that one should practice what one preaches, and that nature is always ready to teach.

To paraphrase the Stoic Musonius, teachers would do well to talk less and to take their students with them into the fields, because there they will learn far better and far more than in the lecture hall.

Teaching Outdoors

|

As early as middle school I knew I wanted to become a college professor, and I love my job. It is a delight to spend time with young people who are curious, after all.

Years ago, my friend Matt Dickerson pointed out to me that it's also my job to help those who are not curious to see why they should be. As it turns out, that work is usually delightful, too, a rewarding challenge.

So on the whole, I love my work.

But I admit I don't love classrooms, for several reasons:

First, no matter what decade, every classroom I've been in has exhibited an unhealthy tendency towards becoming cluttered with the latest technology, and most of that tech seems to take up a lot of space and to become the center of attention. I'm not opposed to technology in the classroom, not at all. But I'm opposed to letting it get in the way, as it does when the "Smart Cart" leaves me no room for my lecture notes, or when I can't seem to turn the ceiling-mounted projector on or off. I'm a fan of chalk, because chalk allows spontaneity, and it allows for much more than alphanumeric writing in neat rows. Sadly, concerns about chalk dust getting into computers is threatening to make chalkboards disappear from my classrooms. Alas. Chalk is an excellent technology, and if it vanishes, I will mourn its loss.

Second, classroom architecture is not some value-free, neutral design. Classroom architecture makes a big difference in how people teach, and how they learn:

|

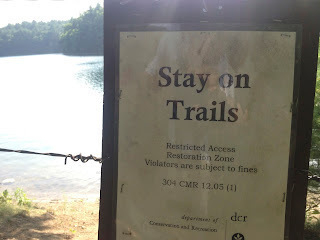

| Step off the trails! Explore! An ironic sign at Walden Pond. |

And this is why I am a preacher of the importance of study abroad. Not just travel, but serious, engaged, rigorous study in the classroom of life in another place. This is why I teach Classics in Greece every year, and why year after year I take students to Central America to study environmental philosophy and ecology.

More and more I've been trying to shift the learning focus in my classes from the classroom to the laboratory - where by "laboratory" I mean anywhere that allows students to learn with their whole person. I make my ancient philosophy students devote hours each semester to star-gazing, in part because this is what the ancients did, and in part because I don't want them to miss the stars. I want them to gaze in wonder at the firmament so that when they read Aristotle and Galileo they know that they've looked at what those great minds saw as well. We even occasionally take field trips to really dark places like the South Dakota Badlands so we can see the skies even better.

My environmental philosophy students must observe a square meter of earth for a semester, spending an hour at a time without a camera, drawing and writing about what they see, because it does not make sense to me to talk about the earth when you have not taken the time to sit upon it, to listen to it, to smell and taste it, and to see what other lives creep, and walk, and fly across it.

My friend Aage Jensen advocates the Norwegian philosophy of Friluftsliv, life and education outdoors. And when he organizes a conference on it, he eschews conference centers and holds the conference while walking through the mountains, or paddling a river. Because he believes that one should practice what one preaches, and that nature is always ready to teach.

To paraphrase the Stoic Musonius, teachers would do well to talk less and to take their students with them into the fields, because there they will learn far better and far more than in the lecture hall.

|

| Nature is full of things worth seeing. |

∞

Mersenne, Education, and Intellectual "Property"

French cleric Marin Mersenne was the academic journal of his day. I have heard it said that in the seventeenth century the saying was "If you want to tell Europe, tell Mersenne."

Hobbes mentions Mersenne several times in his verse autobiography - high praise for a Roman Catholic cleric from someone whose antipathy for the Roman church and its philosophy was both deep and wide. But when Hobbes needed friends during his exile in France, Mersenne was glad to be one of those friends. Mersenne was a friend to all who were engaged in research. He was a living example of that idea of Justin Martyr's that Christians need not fear any books at all, since all the truth they contain belongs to the God who made and sustains it.

He was a friend to Galileo, and he passed Galileo's research on the regular oscillation of pendula along to Huygens in Holland, since he knew Huygens was trying to invent a more regular way of keeping time, leading to the invention of the pendulum clock. He corresponded with Pascal, Gassendi, and Descartes, and what he learned from one he shared with others who could use it.

In his Carnage and Culture, Victor Davis Hanson claims that one of the reasons for technological flourishing in the west is that western cultures treat knowledge as property that can be sold in the marketplace. I can't say whether Hanson's causal inference is correct, but his observation about intellectual "property" is acute.

But alongside it we should add another observation, namely that universities have long been places where ideas are exchanged freely. Yes, students pay tuition, but we also give free public lectures, allow free or inexpensive auditing, etc. What is being sold in the university is not the information but the cost of maintaining a place of intentional colloquy and pedagogy. We aren't selling ideas to students; we are allowing them to join us in the maintenance of a vital institution, and as members of that institution they participate in its life and share in its learning.

Mersenne was not a merchant of ideas but their curator, a steward ushering them to the places they were most needed. He was a gardener who made very few original contributions but who shared the best cultivars he could find with others in whose gardens they could flourish. His approach to knowledge was like that of the church in its earliest years, where "no one claimed private ownership of any possessions, but everything they owned was held in common" and goods were "distributed to each as they had need."

Mersenne's model is relevant to our contemporary conversations about the meaning and cost of an education, the value of universities, and the publication of scientific journals. Some money will be needed to maintain these institutions, but we should resist reducing them to market-based enterprises, or valuing their contributions in terms of revenues. There is also the shared work of curiosity, and of desiring to see our neighbors, and their ideas, flourish.

Hobbes mentions Mersenne several times in his verse autobiography - high praise for a Roman Catholic cleric from someone whose antipathy for the Roman church and its philosophy was both deep and wide. But when Hobbes needed friends during his exile in France, Mersenne was glad to be one of those friends. Mersenne was a friend to all who were engaged in research. He was a living example of that idea of Justin Martyr's that Christians need not fear any books at all, since all the truth they contain belongs to the God who made and sustains it.

He was a friend to Galileo, and he passed Galileo's research on the regular oscillation of pendula along to Huygens in Holland, since he knew Huygens was trying to invent a more regular way of keeping time, leading to the invention of the pendulum clock. He corresponded with Pascal, Gassendi, and Descartes, and what he learned from one he shared with others who could use it.

In his Carnage and Culture, Victor Davis Hanson claims that one of the reasons for technological flourishing in the west is that western cultures treat knowledge as property that can be sold in the marketplace. I can't say whether Hanson's causal inference is correct, but his observation about intellectual "property" is acute.

But alongside it we should add another observation, namely that universities have long been places where ideas are exchanged freely. Yes, students pay tuition, but we also give free public lectures, allow free or inexpensive auditing, etc. What is being sold in the university is not the information but the cost of maintaining a place of intentional colloquy and pedagogy. We aren't selling ideas to students; we are allowing them to join us in the maintenance of a vital institution, and as members of that institution they participate in its life and share in its learning.

Mersenne was not a merchant of ideas but their curator, a steward ushering them to the places they were most needed. He was a gardener who made very few original contributions but who shared the best cultivars he could find with others in whose gardens they could flourish. His approach to knowledge was like that of the church in its earliest years, where "no one claimed private ownership of any possessions, but everything they owned was held in common" and goods were "distributed to each as they had need."

Mersenne's model is relevant to our contemporary conversations about the meaning and cost of an education, the value of universities, and the publication of scientific journals. Some money will be needed to maintain these institutions, but we should resist reducing them to market-based enterprises, or valuing their contributions in terms of revenues. There is also the shared work of curiosity, and of desiring to see our neighbors, and their ideas, flourish.