Graham Greene

- Virginia Woolf, Mrs. Dalloway. (Mixed feelings about this one. My mind enjoyed it more than my aesthetic sense did, if that makes sense.)

- John Steinbeck, Cannery Row and Of Mice and Men. (I discovered Steinbeck late in life, thanks to a friend's recommendation. I've also recently read his Log From The Sea of Cortez and Travels With Charley In Search Of America. I think these two will forever shape me as a writer.)

- Graham Greene, Our Man In Havana, The Quiet American, The Honorary Consul, Travels With My Aunt, The Power And The Glory. (I will let the number of titles speak for itself.)

- Alan Paton, Cry, The Beloved Country. (I was surprised by how contemporary this old book felt, and by how relevant to America an African book could feel.)

- The Táin. Because I have a thing for reading really old books, and this is one of the oldest from Europe.

- China Miéville, Kraken. (London. Magical realism. Bizarre and witty.)

- J. Mark Bertrand, Back On Murder (I don't read many detective novels, but I really enjoy Bertrand's prose.)

- Cormac McCarthy, The Road. (The final lines spoke to my salvelinus fontinalis -loving heart.)

- David James Duncan, The River Why (I've re-read this one a few times. If you like trout and philosophy, you might like this book.)

- Mary Karr, Lit. (Third in a series of memoirs. Some of the best storytelling I've read in a long time. Brilliant insights into addiction, love, and prayer.)

∞

Steinbeck and Greene On Respect For Enemies

These two passages seem like they ought to be put together somehow. The first is from Steinbeck, the second is from Greene. Although the first is non-fiction and the second is fiction, they both deal with the same thing: soldiers who found themselves lamenting the deaths of their enemies, and who admired their enemies' fighting. The two passages remind me, in turn, of Josiah Royce's Philosophy of Loyalty, where he claims that soldiers may be loyal to their fellow soldiers but also to the same spirit of loyalty in their enemies, even though they are not loyal to their enemies themselves. I am also reminded of William James's point in "The Moral Equivalent of War" where he says that no one would repeat the American Civil War, but, just as surely, no one would erase it from history. The conflict engenders virtues and sacrifices that it would be just as wrong to seek as to destroy.

John Steinbeck, Travels With Charley In Search Of America, (New York: Penguin, 1983) 159-160.

Graham Greene, The Quiet American, (New York: Modern Library, 1992) 196-197.

“Some years ago my neighbor was Charles Erskine Scott Wood, who wrote Heavenly Discourse. He was a very old man when I knew him, but as a young lieutenant just out of military academy he had been assigned to General Miles and he served in the Chief Joseph campaign. His memory of it was very clear and very sad. He said it was one of the most gallant retreats in all history. Chief Joseph and the Nez Percés with squaws and children, dogs, and all their possessions, retreated under heavy fire for over a thousand miles, trying to escape to Canada. Wood said they fought every step of the way against odds until finally they were surrounded by the cavalry under General Miles and the large part of them wiped out. It was the saddest duty he had ever performed, Wood said, and he had never lost his respect for the fighting qualities of the Nez Percés. ‘If they hadn’t had their families with them we could never have caught them,” he said. “And if we had been evenly matched in men and weapons, we couldn’t have beaten them. They were men,” he said, “real men.”And here's Greene:

“Trouin said, ‘Today’s affair—that is not the worst for someone like myself. Over the village they could have shot us down. Our risk was as great as theirs. What I detest is napalm bombing. From three thousand feet, in safety.’ He made a hopeless gesture. ‘You see the forest catching fire. God knows what you would see from the ground. The poor devils are burned alive, the flames go over them like water. They are wet through with fire.’ He said with anger against a whole world that didn’t understand, ‘I’m not fighting a colonial war. Do you think I’d do these things for the planters of Terre Rouge? I’d rather be court-martialled. We are fighting all of your wars, but you leave us the guilt.”These are things that I, who have never had to fight a war, can only gaze at from afar, with wonder, and sadness, and gratitude.

*****

John Steinbeck, Travels With Charley In Search Of America, (New York: Penguin, 1983) 159-160.

Graham Greene, The Quiet American, (New York: Modern Library, 1992) 196-197.

∞

Books Worth Reading

After my recent post about great books, pedagogy and hope I've had some queries about what I'm reading and what I recommend.

I'm reluctant to make book recommendations because I think what you read should have some connection to what you care about and what you've already read. In general, my recommendations are these:

First, I agree with what C.S. Lewis once said:* it's good to read old books. Old books and books written by people who are not like us have a remarkable power of helping us to see the world with fresh eyes.

Second, let your reading grow organically. If you liked a book you read, let it lead you to the next book you read. Often, books name their connections to other books. Or authors will name those connections, dependencies, and appreciations. The first time I read Lewis's Out of the Silent Planet, I missed the fact that the preface named H.G. Wells and that the afterword referred to Bernardus Silvestris. When I read it again as an adult, I caught those obvious references and let them lead me to other books.**

Third, I recommend learning the classics. That's an intentionally vague term, and I use it to mean that it's good to know those books that have given your culture its vocabulary. People who have stories in common have enriched possibilities for conversation. One of my favorite Star Trek episodes explored this idea, and it appealed to me because I believe that it's not far from how language really grows. If you need a place to start, check out one of the various lists of "great books" floating around out there. For instance this one, or this one.

With all that being said, if you're still interested in what I'm reading, here are some older titles I've enjoyed in the last year or so:

* Lewis said this in his introduction to Athanasius' On The Incarnation (which, by the way, is now available from SVS Press in a dual-language edition, Greek on one page, English on the facing page.)

** There are two excellent books on Lewis' "Space Trilogy" or (as I think it should be called) "Ransom Trilogy": This one by Sanford Schwartz, and this one by David Downing.

I'm reluctant to make book recommendations because I think what you read should have some connection to what you care about and what you've already read. In general, my recommendations are these:

First, I agree with what C.S. Lewis once said:* it's good to read old books. Old books and books written by people who are not like us have a remarkable power of helping us to see the world with fresh eyes.

Second, let your reading grow organically. If you liked a book you read, let it lead you to the next book you read. Often, books name their connections to other books. Or authors will name those connections, dependencies, and appreciations. The first time I read Lewis's Out of the Silent Planet, I missed the fact that the preface named H.G. Wells and that the afterword referred to Bernardus Silvestris. When I read it again as an adult, I caught those obvious references and let them lead me to other books.**

Third, I recommend learning the classics. That's an intentionally vague term, and I use it to mean that it's good to know those books that have given your culture its vocabulary. People who have stories in common have enriched possibilities for conversation. One of my favorite Star Trek episodes explored this idea, and it appealed to me because I believe that it's not far from how language really grows. If you need a place to start, check out one of the various lists of "great books" floating around out there. For instance this one, or this one.

With all that being said, if you're still interested in what I'm reading, here are some older titles I've enjoyed in the last year or so:

*****

* Lewis said this in his introduction to Athanasius' On The Incarnation (which, by the way, is now available from SVS Press in a dual-language edition, Greek on one page, English on the facing page.)

** There are two excellent books on Lewis' "Space Trilogy" or (as I think it should be called) "Ransom Trilogy": This one by Sanford Schwartz, and this one by David Downing.

*****

I realize I'm posting a lot about Great Books and St John's College lately. I'll stop soon. They don't pay me for this; I'm just a grateful alumnus.

*****

Update, 8/11/14: I've posted another list like this one on my blog, with new recommendations. You can find it here.

∞

Great Books, Pedagogy, and Hope

Great Books and the Great Conversation

About fifteen years ago I enrolled in the "Great Books" M.A. program at St John's College in Santa Fe, New Mexico. It was one of the best decisions I've ever made.

Much as I appreciate my undergraduate education, too often it rewarded me for concealing my ignorance and emphasizing what I already knew. The problem, of course, is that my ignorance was thus shielded from the sterilizing sunlight of others' scrutiny and instruction.

Confessing Our Ignorance

Matthew Davis, my tutor and advisor at St John's, won me over to another way of viewing literature when, on one of the first days we met, he pointed to a passage in Plato's Republic and said "I have always wondered what Plato means by that." Looking up at the class, he asked, "Do any of you have any ideas about what he might be trying to say?"

Mr. Davis is the first professor I recall who openly confessed his ignorance, and who thereby modeled what it means to open oneself to the instruction of a great text. Not much has shaped my academic life as much as that.

Grappling With Classic Texts

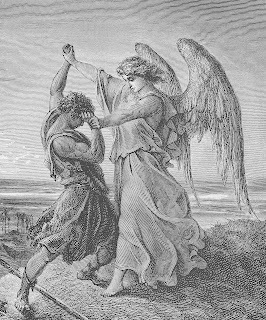

As I have begun to mature into my own place as a teacher, I often think that this is the best thing I can give my students: not professorial and authoritative descriptions of texts, but an example of what it means to be a student. I can try to be an example of someone who sits with texts and listens to them, grappling with them, like Jacob with the angel or like Menelaus with Proteus: persistently grappling with my superior and refusing to let go until I receive a blessing. (Selah.)

For the last few years I have been seeking out and reading classic novels. As I read them I feel like an apprentice architect touring buildings, looking not just at the outward form and function but looking for the supporting structure, trying to notice the decisions the artist made about what to include and what to omit.

Along the way, I have begun trying to write bits of dialogue, scenes, characters, and other elements of fiction. I'm not trying to write a novel so much as trying to perform experiments the way high school science students do in labs: not to discover something new but to learn haptically, kinesthetically, experientially what the masters already know. I can't say that I've learned to write novels, so don't expect anything from me there. But as I've paid attention, I feel I've begun to squeeze some blessings out of the books, including some unexpected ones.

I've noticed, for instance, that Craig Nova writes about the olfactory sense in a way that makes me notice aromas I never noticed before. John Steinbeck has begun to make me care more about friendship, and about the people in front of me. Harold Frederic has me rethinking my early faith, and this is helping me look ahead as I try to nurture it into a faith worth having. Novels are helping me see the world differently.

So What Does This Have To Do With Hope?

I just finished Graham Greene's The Honorary Consul. Apparently this was Greene's favorite of his own works, and I can see why. Like many of the really good novels I've read, it has left me thinking about a range of topics, and longing for someone to talk about it with.

Which brings me to hope. I started reading Greene because Bill Swart, my friend and colleague, told me about how good Greene's novels are. Bill was right about this, so I sought him out the other day to talk more about Greene. We said too much to cover it all here, but Bill said something I can't bear not to repeat. When we began discussing Greene's The Power and the Glory, Bill said "That book gave me hope that my own self-perception might be wrong."

If you know the novel, you know why, because you know how Greene's characters wrestle with being both sinners and saints. If you don't know the novel, let me recommend it to you.

We Should Keep Teaching And Reading Fiction

I still have a lot to learn about novels. I doubt I'll ever write one - or a good one, anyway. But I'm delighting in reading them. Perhaps that's why they matter so much: they delight us, and capture us. When I'm in a good book I feel like I'm really in it. I stop seeing words on a page and start seeing, with some inner eye, the world the novelist sees.

And like all my other travels, journeys into fiction leave me a different person. I see different possibilities, I see -- and smell -- my world differently. I know it's important to teach young people to read non-fiction, but teaching fiction might be for them what The Power and the Glory was for Bill: a tonic for his soul, a sweet drink of hope that didn't just entertain, but that allowed him to envision his life, his work, and his purpose in an entirely new way.

About fifteen years ago I enrolled in the "Great Books" M.A. program at St John's College in Santa Fe, New Mexico. It was one of the best decisions I've ever made.

Much as I appreciate my undergraduate education, too often it rewarded me for concealing my ignorance and emphasizing what I already knew. The problem, of course, is that my ignorance was thus shielded from the sterilizing sunlight of others' scrutiny and instruction.

Confessing Our Ignorance

Matthew Davis, my tutor and advisor at St John's, won me over to another way of viewing literature when, on one of the first days we met, he pointed to a passage in Plato's Republic and said "I have always wondered what Plato means by that." Looking up at the class, he asked, "Do any of you have any ideas about what he might be trying to say?"

Mr. Davis is the first professor I recall who openly confessed his ignorance, and who thereby modeled what it means to open oneself to the instruction of a great text. Not much has shaped my academic life as much as that.

Grappling With Classic Texts

As I have begun to mature into my own place as a teacher, I often think that this is the best thing I can give my students: not professorial and authoritative descriptions of texts, but an example of what it means to be a student. I can try to be an example of someone who sits with texts and listens to them, grappling with them, like Jacob with the angel or like Menelaus with Proteus: persistently grappling with my superior and refusing to let go until I receive a blessing. (Selah.)

For the last few years I have been seeking out and reading classic novels. As I read them I feel like an apprentice architect touring buildings, looking not just at the outward form and function but looking for the supporting structure, trying to notice the decisions the artist made about what to include and what to omit.

Along the way, I have begun trying to write bits of dialogue, scenes, characters, and other elements of fiction. I'm not trying to write a novel so much as trying to perform experiments the way high school science students do in labs: not to discover something new but to learn haptically, kinesthetically, experientially what the masters already know. I can't say that I've learned to write novels, so don't expect anything from me there. But as I've paid attention, I feel I've begun to squeeze some blessings out of the books, including some unexpected ones.

I've noticed, for instance, that Craig Nova writes about the olfactory sense in a way that makes me notice aromas I never noticed before. John Steinbeck has begun to make me care more about friendship, and about the people in front of me. Harold Frederic has me rethinking my early faith, and this is helping me look ahead as I try to nurture it into a faith worth having. Novels are helping me see the world differently.

So What Does This Have To Do With Hope?

I just finished Graham Greene's The Honorary Consul. Apparently this was Greene's favorite of his own works, and I can see why. Like many of the really good novels I've read, it has left me thinking about a range of topics, and longing for someone to talk about it with.

Which brings me to hope. I started reading Greene because Bill Swart, my friend and colleague, told me about how good Greene's novels are. Bill was right about this, so I sought him out the other day to talk more about Greene. We said too much to cover it all here, but Bill said something I can't bear not to repeat. When we began discussing Greene's The Power and the Glory, Bill said "That book gave me hope that my own self-perception might be wrong."

If you know the novel, you know why, because you know how Greene's characters wrestle with being both sinners and saints. If you don't know the novel, let me recommend it to you.

We Should Keep Teaching And Reading Fiction

I still have a lot to learn about novels. I doubt I'll ever write one - or a good one, anyway. But I'm delighting in reading them. Perhaps that's why they matter so much: they delight us, and capture us. When I'm in a good book I feel like I'm really in it. I stop seeing words on a page and start seeing, with some inner eye, the world the novelist sees.

And like all my other travels, journeys into fiction leave me a different person. I see different possibilities, I see -- and smell -- my world differently. I know it's important to teach young people to read non-fiction, but teaching fiction might be for them what The Power and the Glory was for Bill: a tonic for his soul, a sweet drink of hope that didn't just entertain, but that allowed him to envision his life, his work, and his purpose in an entirely new way.