Greece

- This too is related to technology, of course. If the class is focused on video screens, then all the chairs will face the screens, and the classroom might even be structured like a theater. Etymologically, "theater" means something like "a place of gazing," and theaters tend to encourage people to gaze. Sometimes this can work against other activities, like colloquy, small-group interaction, and really anything that involves students moving from one place to another.

- If that last sentence made you ask,"But why do you want your students to move from one place to another?" then you see that we have some pretty strong presuppositions about how education should happen: students should sit and listen, teachers should stand and lecture. This communicates something about authority, and at times that's helpful. But it can also invite students to lean back into passivity, and to assume they have no role in their own education.

- The furniture in classrooms tells us how people are to behave, because it has been made and purchased by people who had in mind some idea of how students should behave. Most wrap-around desks are made for right-handed people, for instance. And most classroom desks I've seen expect students to sit upright, at attention, with a book open in front of them. I really don't like those desks, and I feel trapped when I sit in them. I wonder sometimes how they make my students feel. I wish we had fewer chairs and more sofas. Maybe a fireplace, or some tables with glasses of water, and ashtrays on them. I suppose I wish I could teach in pubs or ratskellers, which are, after all, places consciously designed for people to meet and discuss what most matters to them, informally, passionately, amicably.

- Classrooms that privilege video screens tend to undervalue natural light and windows. I am reminded of Emerson's reflection on a boring sermon he once heard. Emerson wrote, in his Divinity School Address, that while the minister droned on, Emerson looked out the window at the falling snow, which, he proclaimed, preached a better sermon than the minister. I have no doubt that nature can often give a better lecture than I can.

∞

The Trace I Left Behind

This summer I spent several weeks in and around Lake Clark National Park doing research on trout, salmon, and char.

Sometimes I get quizzical looks when I say that I, a philosophy and classics professor, am researching fish. Let me explain.

I teach environmental philosophy and a range of classes in what I call "environmental humanities." These include courses in environmental ethics, nature writing, philosophy of nature, and even a course on environmental law and policy for first-year undergraduates, as an introduction to being a university student.

I also teach courses in field ecology, including a monthlong course in tropical ecology in Guatemala and Belize. I teach in Greece over my spring break, and this year we will be looking at the expansion of fish farms in the Mediterranean and how fishing has changed there over the last six thousand years.

Closer to home, I teach and practice what Norwegians call friluftsliv, or life in the free air. Whenever possible, I teach outdoors. Most years, I take my ancient philosophy students camping in the Badlands National Park to watch the Orionid meteor shower while we lie on sleeping bags under the stars.

In all of this, my aim is to make sure that nature is not an abstraction to my students, nor to me. I want to know the places the fish live, the grasslands the bison roam, the forests where the jaguar and the ocelot hunt, the tundra rivers where the Dolly Varden chase the salmon under the watchful gaze of the bears.

In other words, my aim is to stay in contact with wildness, and to do so in a way that allows me to take something valuable home: intimate knowledge. I am not a scientist, so I don't bring samples back to a laboratory. I do bring home photographs, and I do spend a lot of time making observations of the places I work, so that I can bring home notebooks full of writing to share with my students. And of course, I write books and articles to share with others.

This summer, I was sorely tempted to bring something else home from Lake Clark: a tiny fossil. I had chartered a float plane to take me to a fairly remote lake, and there my fellow researchers and I walked the shore to the mouth of a stream full of spawning salmon and rainbow trout.

As I often do, I sat down on the gravel and started to turn over rocks to see what invertebrates were living there. The salmon are bright red and eye-catching, but the bugs and spiders tell an important part of the story of a place, as Kurt Fausch has written about in his recent book, For The Love Of Rivers. Who was it - J.B.S. Haldane, perhaps? - who quipped that God has "an inordinate fondness for beetles." The world is full of wonderful, tiny lives that are easy to overlook.

I don't try to bring beetles home, but one insect tempted me this summer. Really, it was just a trace of an insect, just the trace of its wings, in fact. I can't even tell you what insect it was. All I can tell you is that somewhere near that river, probably millions of years ago, something like a dragonfly died in the mud, and the river graced its delicate wings with the cerement of silt. That silt took the form of the wings, those wings left a fingerprint - a wingprint - on the earth. And this summer, I found that print, that delicate, wonderful trace.

While my son and my friend and our pilot walked, I sat with that stone in my hand and thought about pocketing it. Here I was in the wilderness, and no one would know. It's one tiny stone in the largest state in the union; who would miss it?

Ah, but it is one tiny stone that does not belong to me. It is one tiny stone in a vast wilderness that belongs to all of us, and to all who will come after us. It is one tiny piece of rock with an incomplete fossil of a little odonata. The river there has held it and cared for it since time immemorial.

Now I am back in South Dakota, but a tiny trace of my heart remains along the strand of that stream in Alaska. It lies there, wrapped around that delicate trace of insect wing, and I will never find it again in that vast wilderness.

But perhaps someone else will. Until then, perhaps it is best not to let Midas' longings turn our hearts to stone too soon. Let's walk the shores together, I will continue to say to my students. And let's bring something intangible home in our memories. And let's do the hard work of leaving behind the beautiful, delicate traces that wildness has safeguarded for so many, many years.

Sometimes I get quizzical looks when I say that I, a philosophy and classics professor, am researching fish. Let me explain.

I teach environmental philosophy and a range of classes in what I call "environmental humanities." These include courses in environmental ethics, nature writing, philosophy of nature, and even a course on environmental law and policy for first-year undergraduates, as an introduction to being a university student.

I also teach courses in field ecology, including a monthlong course in tropical ecology in Guatemala and Belize. I teach in Greece over my spring break, and this year we will be looking at the expansion of fish farms in the Mediterranean and how fishing has changed there over the last six thousand years.

Closer to home, I teach and practice what Norwegians call friluftsliv, or life in the free air. Whenever possible, I teach outdoors. Most years, I take my ancient philosophy students camping in the Badlands National Park to watch the Orionid meteor shower while we lie on sleeping bags under the stars.

In all of this, my aim is to make sure that nature is not an abstraction to my students, nor to me. I want to know the places the fish live, the grasslands the bison roam, the forests where the jaguar and the ocelot hunt, the tundra rivers where the Dolly Varden chase the salmon under the watchful gaze of the bears.

In other words, my aim is to stay in contact with wildness, and to do so in a way that allows me to take something valuable home: intimate knowledge. I am not a scientist, so I don't bring samples back to a laboratory. I do bring home photographs, and I do spend a lot of time making observations of the places I work, so that I can bring home notebooks full of writing to share with my students. And of course, I write books and articles to share with others.

This summer, I was sorely tempted to bring something else home from Lake Clark: a tiny fossil. I had chartered a float plane to take me to a fairly remote lake, and there my fellow researchers and I walked the shore to the mouth of a stream full of spawning salmon and rainbow trout.

|

| Salmon preparing to spawn |

As I often do, I sat down on the gravel and started to turn over rocks to see what invertebrates were living there. The salmon are bright red and eye-catching, but the bugs and spiders tell an important part of the story of a place, as Kurt Fausch has written about in his recent book, For The Love Of Rivers. Who was it - J.B.S. Haldane, perhaps? - who quipped that God has "an inordinate fondness for beetles." The world is full of wonderful, tiny lives that are easy to overlook.

I don't try to bring beetles home, but one insect tempted me this summer. Really, it was just a trace of an insect, just the trace of its wings, in fact. I can't even tell you what insect it was. All I can tell you is that somewhere near that river, probably millions of years ago, something like a dragonfly died in the mud, and the river graced its delicate wings with the cerement of silt. That silt took the form of the wings, those wings left a fingerprint - a wingprint - on the earth. And this summer, I found that print, that delicate, wonderful trace.

|

| Fossilized trace of an insect's wing |

While my son and my friend and our pilot walked, I sat with that stone in my hand and thought about pocketing it. Here I was in the wilderness, and no one would know. It's one tiny stone in the largest state in the union; who would miss it?

Ah, but it is one tiny stone that does not belong to me. It is one tiny stone in a vast wilderness that belongs to all of us, and to all who will come after us. It is one tiny piece of rock with an incomplete fossil of a little odonata. The river there has held it and cared for it since time immemorial.

Now I am back in South Dakota, but a tiny trace of my heart remains along the strand of that stream in Alaska. It lies there, wrapped around that delicate trace of insect wing, and I will never find it again in that vast wilderness.

But perhaps someone else will. Until then, perhaps it is best not to let Midas' longings turn our hearts to stone too soon. Let's walk the shores together, I will continue to say to my students. And let's bring something intangible home in our memories. And let's do the hard work of leaving behind the beautiful, delicate traces that wildness has safeguarded for so many, many years.

∞

A Pretty Good Year

Last year was a pretty good year. Or at least, what I remember of it was pretty good.

As my regular readers know, I'm a professor of philosophy and classics, and I teach a wide range of classes. (You can click on the "Teaching" link above to see a sampling of the courses I teach.)

Often people assume that means I wear tweed and a bowtie and that I spend my time in classrooms talking about old books. All that is true, but it's only a part of what I do.

In fact, most of my favorite classrooms are outdoors, where I'm likely to be found wearing jeans and hiking boots, a parka, or a wetsuit and snorkel.

Over the last dozen years or so my teaching and research have tended towards the environmental humanities. Think of this as the merging of the humanities side of the liberal arts with a close observation of the natural world. I consider my work to be a continuation of the work that Thales and Aristotle did when they paid close attention to animals on the ground and to the skies above, and of the work of Peirce, Thoreau, and Bugbee, all of whom let a rising trout or a solar eclipse provoke philosophical reflection.

While I don't work in an indoor laboratory, I think that education is not about the imparting of information or the filling of an empty vessel with ideas. Education is the kindling of a fire, as Plutarch wrote. And that fire is kindled by the kinds of experiences that we get in labs, art studios, shared meals, liturgies, study travel, and seminars. Lecture halls are a fine place to discuss environmental policy, to be sure. But so is a prairie, especially when you're waiting for water to boil on your camp stove, and watching the sun's beams break over the horizon and melt a light frost on your tent.

When I'm at home, I like to take my classes outside to sit under trees on campus. In the fall, I try to bring my Ancient Philosophy students camping in the Badlands of South Dakota where we can view the stars far from urban glow. Most Januaries, my students and I are in the subtropical forests of Guatemala and on a barrier island in Belize, studying ecology and culture. I rarely take a spring break, since I usually take that week to teach a course in Greece. Last summer I started teaching a class on trout and salmon in Alaska.

Those are all beautiful, memorable places, but I don't visit them as a tourist. I go to these places because I want my students to understand what is at stake when we talk about environmental regulations and practices. I want them to meet displaced people whose permafrost islands are melting or whose forests are being burned down for meager cropland. I want them to see the disappearing mangroves so that they can consider the full cost of seafood. When they stay in homes in Guatemala, my students will meet people who can never again be a mere abstraction; after we return, my students will know that the people struggling to cross borders are not nameless, faceless strangers, but people who are looking for ways to feed those they love.

A little less than a year ago I was finishing up a year that had brought me to all these places. I taught in the South Dakota Badlands, in Central America, in Greece, and in Alaska. Along the way, I had begun studying environmental law at Vermont Law School as a way of enhancing my teaching and my research. It was a good year, and as August was winding down, my desk was covered with field notebooks full of observations from Alaska and Guatemala, ready to be written up. My field notes are usually accompanied by thousands of photographs, and hundreds of sketches. I began the fall semester last year ready to teach, and ready to write.

And then I wound up in the hospital with some serious injuries. Those injuries put a sudden stop to all my teaching last fall, and for a long time I lost most of my ability to write. (I'll try to write more about the injuries and my subsequent disabilities later; it's not an easy thing to write about yet.)

Now, as this summer hastens towards the beginning of another school year, I am able to look back on last year with a sense of good fortune - albeit mixed with one very bad day and its long-term consequences. Physically, I'm regaining my flexibility and strength, a little at a time. I'm not where I was a year ago, and I may never be there again, but I'm alive and able to walk, so I'll count that in the "win" column of my life's scorecard. Intellectually, most people seem to think I'm doing fine, so I'll also count that as a win. Although it left me exhausted each day, I was able to teach again this spring, and I plan to be back in my classrooms (Deo volente!) this fall.

But here are these field notebooks, and hundreds of unedited pages on my hard drive. It was my habit to write daily. Over the last year, recovering from a brain injury has made it hard to write more than a few sentences at a time.

This morning I was looking at some of my pictures from my research in the Arctic last summer, and I was hit with a feeling of loss. Those photos and those notes should be a book by now, and perhaps several articles and book chapters, too. Instead, over the last year, as I have waited for my body and brain to heal, and as I struggled to do my teaching, I had no strength to write.

It feels funny to say that, but perhaps I am not alone in finding that a brain injury can be slow to heal and extremely tiring. I don't say that to get your sympathy. I am blessed with a very supportive community and an amazing wife who somehow has kept our life together and nursed me through my healing process. I'm fortunate. But if you've read this far, you might consider whether there are others around you who look like they're doing well physically but who might be nursing invisible wounds or who might be struggling to cope with invisible disabilities. This past year has given me a new perspective on that by making me aware of my own disabilities, most of which you won't notice if you see me at the gym or in one of my classrooms.

I might not be able to write another book yet, so for now, here's my plan: I'll write a little at a time. Thankfully, I've got my notes, sketches, and photos. I'll start with them.

If you're curious about how a professor of philosophy and classics does research and writing about nature - and how he works to recover from a serious brain injury - you might check out some of my recent publications. My book Downstream is the result of eight years of field research on the ecology of the Appalachians, with a focus on brook trout. On this blog you'll also find my recently published poem, "Sage Creek," which might give you a glimpse of my ancient philosophy class camping and stargazing in the Badlands. Or feel free to look at my photos on Instagram. Even when I can't teach in the field, I can still wander my garden with a hand lens and camera.

As my regular readers know, I'm a professor of philosophy and classics, and I teach a wide range of classes. (You can click on the "Teaching" link above to see a sampling of the courses I teach.)

Often people assume that means I wear tweed and a bowtie and that I spend my time in classrooms talking about old books. All that is true, but it's only a part of what I do.

In fact, most of my favorite classrooms are outdoors, where I'm likely to be found wearing jeans and hiking boots, a parka, or a wetsuit and snorkel.

Over the last dozen years or so my teaching and research have tended towards the environmental humanities. Think of this as the merging of the humanities side of the liberal arts with a close observation of the natural world. I consider my work to be a continuation of the work that Thales and Aristotle did when they paid close attention to animals on the ground and to the skies above, and of the work of Peirce, Thoreau, and Bugbee, all of whom let a rising trout or a solar eclipse provoke philosophical reflection.

While I don't work in an indoor laboratory, I think that education is not about the imparting of information or the filling of an empty vessel with ideas. Education is the kindling of a fire, as Plutarch wrote. And that fire is kindled by the kinds of experiences that we get in labs, art studios, shared meals, liturgies, study travel, and seminars. Lecture halls are a fine place to discuss environmental policy, to be sure. But so is a prairie, especially when you're waiting for water to boil on your camp stove, and watching the sun's beams break over the horizon and melt a light frost on your tent.

When I'm at home, I like to take my classes outside to sit under trees on campus. In the fall, I try to bring my Ancient Philosophy students camping in the Badlands of South Dakota where we can view the stars far from urban glow. Most Januaries, my students and I are in the subtropical forests of Guatemala and on a barrier island in Belize, studying ecology and culture. I rarely take a spring break, since I usually take that week to teach a course in Greece. Last summer I started teaching a class on trout and salmon in Alaska.

Those are all beautiful, memorable places, but I don't visit them as a tourist. I go to these places because I want my students to understand what is at stake when we talk about environmental regulations and practices. I want them to meet displaced people whose permafrost islands are melting or whose forests are being burned down for meager cropland. I want them to see the disappearing mangroves so that they can consider the full cost of seafood. When they stay in homes in Guatemala, my students will meet people who can never again be a mere abstraction; after we return, my students will know that the people struggling to cross borders are not nameless, faceless strangers, but people who are looking for ways to feed those they love.

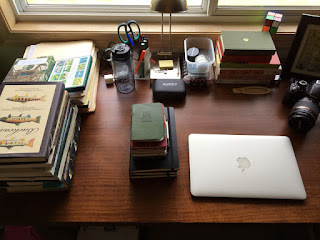

A little less than a year ago I was finishing up a year that had brought me to all these places. I taught in the South Dakota Badlands, in Central America, in Greece, and in Alaska. Along the way, I had begun studying environmental law at Vermont Law School as a way of enhancing my teaching and my research. It was a good year, and as August was winding down, my desk was covered with field notebooks full of observations from Alaska and Guatemala, ready to be written up. My field notes are usually accompanied by thousands of photographs, and hundreds of sketches. I began the fall semester last year ready to teach, and ready to write.

|

| Field notes. A picture of some of the work I do when I'm inside, and not teaching; or, if you like, a picture of my desk as I recover from my injuries. I have a lot of catching up to do. |

And then I wound up in the hospital with some serious injuries. Those injuries put a sudden stop to all my teaching last fall, and for a long time I lost most of my ability to write. (I'll try to write more about the injuries and my subsequent disabilities later; it's not an easy thing to write about yet.)

Now, as this summer hastens towards the beginning of another school year, I am able to look back on last year with a sense of good fortune - albeit mixed with one very bad day and its long-term consequences. Physically, I'm regaining my flexibility and strength, a little at a time. I'm not where I was a year ago, and I may never be there again, but I'm alive and able to walk, so I'll count that in the "win" column of my life's scorecard. Intellectually, most people seem to think I'm doing fine, so I'll also count that as a win. Although it left me exhausted each day, I was able to teach again this spring, and I plan to be back in my classrooms (Deo volente!) this fall.

But here are these field notebooks, and hundreds of unedited pages on my hard drive. It was my habit to write daily. Over the last year, recovering from a brain injury has made it hard to write more than a few sentences at a time.

This morning I was looking at some of my pictures from my research in the Arctic last summer, and I was hit with a feeling of loss. Those photos and those notes should be a book by now, and perhaps several articles and book chapters, too. Instead, over the last year, as I have waited for my body and brain to heal, and as I struggled to do my teaching, I had no strength to write.

It feels funny to say that, but perhaps I am not alone in finding that a brain injury can be slow to heal and extremely tiring. I don't say that to get your sympathy. I am blessed with a very supportive community and an amazing wife who somehow has kept our life together and nursed me through my healing process. I'm fortunate. But if you've read this far, you might consider whether there are others around you who look like they're doing well physically but who might be nursing invisible wounds or who might be struggling to cope with invisible disabilities. This past year has given me a new perspective on that by making me aware of my own disabilities, most of which you won't notice if you see me at the gym or in one of my classrooms.

I might not be able to write another book yet, so for now, here's my plan: I'll write a little at a time. Thankfully, I've got my notes, sketches, and photos. I'll start with them.

If you're curious about how a professor of philosophy and classics does research and writing about nature - and how he works to recover from a serious brain injury - you might check out some of my recent publications. My book Downstream is the result of eight years of field research on the ecology of the Appalachians, with a focus on brook trout. On this blog you'll also find my recently published poem, "Sage Creek," which might give you a glimpse of my ancient philosophy class camping and stargazing in the Badlands. Or feel free to look at my photos on Instagram. Even when I can't teach in the field, I can still wander my garden with a hand lens and camera.

∞

As September approaches, people keep asking me, "Are you ready to get back in the classroom?"

As early as middle school I knew I wanted to become a college professor, and I love my job. It is a delight to spend time with young people who are curious, after all.

Years ago, my friend Matt Dickerson pointed out to me that it's also my job to help those who are not curious to see why they should be. As it turns out, that work is usually delightful, too, a rewarding challenge.

So on the whole, I love my work.

But I admit I don't love classrooms, for several reasons:

First, no matter what decade, every classroom I've been in has exhibited an unhealthy tendency towards becoming cluttered with the latest technology, and most of that tech seems to take up a lot of space and to become the center of attention. I'm not opposed to technology in the classroom, not at all. But I'm opposed to letting it get in the way, as it does when the "Smart Cart" leaves me no room for my lecture notes, or when I can't seem to turn the ceiling-mounted projector on or off. I'm a fan of chalk, because chalk allows spontaneity, and it allows for much more than alphanumeric writing in neat rows. Sadly, concerns about chalk dust getting into computers is threatening to make chalkboards disappear from my classrooms. Alas. Chalk is an excellent technology, and if it vanishes, I will mourn its loss.

Second, classroom architecture is not some value-free, neutral design. Classroom architecture makes a big difference in how people teach, and how they learn:

Which is why, as often as I can, I get my students out of the classroom. When we are reading Thoreau's Walking, we go for a walk. When I teach environmental philosophy, we often meet under the great tree in our campus quad, where I encourage students to daydream and to play with the grass, to look for worm-castings and owl pellets, feathers and seed-pods, invertebrates and fallen bits of bark. What good is it to gain the world of theoretical knowledge at the expense of knowledge gained through vital, haptic, bodily experience?

And this is why I am a preacher of the importance of study abroad. Not just travel, but serious, engaged, rigorous study in the classroom of life in another place. This is why I teach Classics in Greece every year, and why year after year I take students to Central America to study environmental philosophy and ecology.

More and more I've been trying to shift the learning focus in my classes from the classroom to the laboratory - where by "laboratory" I mean anywhere that allows students to learn with their whole person. I make my ancient philosophy students devote hours each semester to star-gazing, in part because this is what the ancients did, and in part because I don't want them to miss the stars. I want them to gaze in wonder at the firmament so that when they read Aristotle and Galileo they know that they've looked at what those great minds saw as well. We even occasionally take field trips to really dark places like the South Dakota Badlands so we can see the skies even better.

My environmental philosophy students must observe a square meter of earth for a semester, spending an hour at a time without a camera, drawing and writing about what they see, because it does not make sense to me to talk about the earth when you have not taken the time to sit upon it, to listen to it, to smell and taste it, and to see what other lives creep, and walk, and fly across it.

My friend Aage Jensen advocates the Norwegian philosophy of Friluftsliv, life and education outdoors. And when he organizes a conference on it, he eschews conference centers and holds the conference while walking through the mountains, or paddling a river. Because he believes that one should practice what one preaches, and that nature is always ready to teach.

To paraphrase the Stoic Musonius, teachers would do well to talk less and to take their students with them into the fields, because there they will learn far better and far more than in the lecture hall.

Teaching Outdoors

|

As early as middle school I knew I wanted to become a college professor, and I love my job. It is a delight to spend time with young people who are curious, after all.

Years ago, my friend Matt Dickerson pointed out to me that it's also my job to help those who are not curious to see why they should be. As it turns out, that work is usually delightful, too, a rewarding challenge.

So on the whole, I love my work.

But I admit I don't love classrooms, for several reasons:

First, no matter what decade, every classroom I've been in has exhibited an unhealthy tendency towards becoming cluttered with the latest technology, and most of that tech seems to take up a lot of space and to become the center of attention. I'm not opposed to technology in the classroom, not at all. But I'm opposed to letting it get in the way, as it does when the "Smart Cart" leaves me no room for my lecture notes, or when I can't seem to turn the ceiling-mounted projector on or off. I'm a fan of chalk, because chalk allows spontaneity, and it allows for much more than alphanumeric writing in neat rows. Sadly, concerns about chalk dust getting into computers is threatening to make chalkboards disappear from my classrooms. Alas. Chalk is an excellent technology, and if it vanishes, I will mourn its loss.

Second, classroom architecture is not some value-free, neutral design. Classroom architecture makes a big difference in how people teach, and how they learn:

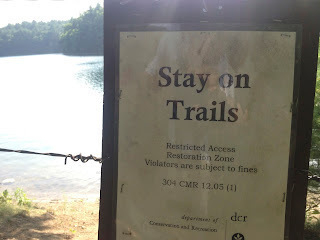

|

| Step off the trails! Explore! An ironic sign at Walden Pond. |

And this is why I am a preacher of the importance of study abroad. Not just travel, but serious, engaged, rigorous study in the classroom of life in another place. This is why I teach Classics in Greece every year, and why year after year I take students to Central America to study environmental philosophy and ecology.

More and more I've been trying to shift the learning focus in my classes from the classroom to the laboratory - where by "laboratory" I mean anywhere that allows students to learn with their whole person. I make my ancient philosophy students devote hours each semester to star-gazing, in part because this is what the ancients did, and in part because I don't want them to miss the stars. I want them to gaze in wonder at the firmament so that when they read Aristotle and Galileo they know that they've looked at what those great minds saw as well. We even occasionally take field trips to really dark places like the South Dakota Badlands so we can see the skies even better.

My environmental philosophy students must observe a square meter of earth for a semester, spending an hour at a time without a camera, drawing and writing about what they see, because it does not make sense to me to talk about the earth when you have not taken the time to sit upon it, to listen to it, to smell and taste it, and to see what other lives creep, and walk, and fly across it.

My friend Aage Jensen advocates the Norwegian philosophy of Friluftsliv, life and education outdoors. And when he organizes a conference on it, he eschews conference centers and holds the conference while walking through the mountains, or paddling a river. Because he believes that one should practice what one preaches, and that nature is always ready to teach.

To paraphrase the Stoic Musonius, teachers would do well to talk less and to take their students with them into the fields, because there they will learn far better and far more than in the lecture hall.

|

| Nature is full of things worth seeing. |

∞

"Life Is Our Dictionary"

"Authors we have in numbers, who have written out their vein, and who, moved by a commendable prudence, set sail for Greece or Palestine, follow the trapper into the prairie, or ramble round Algiers to replenish their merchantable stock. If it were only for a vocabulary the scholar would be covetous of action. Life is our dictionary."

R.W. Emerson, "The American Scholar"

∞

Visual Art and the Sacred: On The Importance Of Museums

I just finished writing an essay about the day Picasso made me fall down. I'm sending it off to my favorite editor, and if it's accepted, I'll post a link here.

The event I wrote about took place over two decades ago, when Picasso's Guernica was still housed in the Casón del Buen Retiro at the Prado Museum in Madrid. (It is now in the Reina Sofia, in a larger but - in my opinion - far inferior room. You can learn a bit about that here.)

Meanwhile, here's the upshot of my essay: education that's prepackaged and canned is not enough. Education is not the same as transferring information.

It involves informing students, to be sure, but what we tell students

should not satisfy them; it should provoke them to want more. Professors are not conduits of data; at our best we are like guides and gardeners.

As guides we point students in new directions and help them to see what

we see. Just as gardeners cannot make seeds grow but can prepare the

soil, so our teaching should be about increasing the fertility of minds

and then stepping back to watch what grows. Also, there is occasional

weeding involved.

As an undergraduate I knew very little about art. Part of this was my disposition: I liked representational art that was easy to look at quickly. Part of it was a matter of my worldview, and the suspicion that some modern artists who eschewed representational art were trying to undermine something good, obscurantists clouding clear vision.

Time spent in museums has changed me a good deal, as has making the acquaintance of Scott Parsons and Daniel Siedell, who have helped me quite a lot through their patient conversation and what they have written. (Scott and I wrote a chapter on teaching students about visual culture and the sacred in Ronald Bernier's short but illuminating book Beyond Belief, in which Dan also has a chapter.) Some of Makoto Fujimura's short writings, James Elkins's book On the Strange Place of Religion in Modern Art, and Gregory Wolfe's work at Image have also provided me with clear and helpful education about art that I resisted when I was younger.

Museums are certainly controversial. Curators make decisions that both expand and limit what we see, and this can be exploited to achieve sordid political ends. Some ideas and cultures are given preferential treatment while others are made less known by their omission. They tend to be located in large, wealthy cities, which means that poor people, rural people, and foreigners have limited or no access to them. But if the alternative is no museums, or all of the world's artifacts in private collections, I will take the museums we have, coupled with ever striving to make them better.

Because museums are a tangible way we can commit to remembering our history together. Museums are not safe deposit boxes where we lock away our treasures; they are Wunderkammers and classrooms where we may think and learn together.

I have come to love museums, especially the British Museum and the beautiful New Acropolis Museum in Athens (and I'm aware of the irony of that pairing) but I also love the little museums I find in small towns the world over.

The event I wrote about took place over two decades ago, when Picasso's Guernica was still housed in the Casón del Buen Retiro at the Prado Museum in Madrid. (It is now in the Reina Sofia, in a larger but - in my opinion - far inferior room. You can learn a bit about that here.)

|

| New Acropolis Museum, Athens |

As an undergraduate I knew very little about art. Part of this was my disposition: I liked representational art that was easy to look at quickly. Part of it was a matter of my worldview, and the suspicion that some modern artists who eschewed representational art were trying to undermine something good, obscurantists clouding clear vision.

Time spent in museums has changed me a good deal, as has making the acquaintance of Scott Parsons and Daniel Siedell, who have helped me quite a lot through their patient conversation and what they have written. (Scott and I wrote a chapter on teaching students about visual culture and the sacred in Ronald Bernier's short but illuminating book Beyond Belief, in which Dan also has a chapter.) Some of Makoto Fujimura's short writings, James Elkins's book On the Strange Place of Religion in Modern Art, and Gregory Wolfe's work at Image have also provided me with clear and helpful education about art that I resisted when I was younger.

Museums are certainly controversial. Curators make decisions that both expand and limit what we see, and this can be exploited to achieve sordid political ends. Some ideas and cultures are given preferential treatment while others are made less known by their omission. They tend to be located in large, wealthy cities, which means that poor people, rural people, and foreigners have limited or no access to them. But if the alternative is no museums, or all of the world's artifacts in private collections, I will take the museums we have, coupled with ever striving to make them better.

Because museums are a tangible way we can commit to remembering our history together. Museums are not safe deposit boxes where we lock away our treasures; they are Wunderkammers and classrooms where we may think and learn together.

I have come to love museums, especially the British Museum and the beautiful New Acropolis Museum in Athens (and I'm aware of the irony of that pairing) but I also love the little museums I find in small towns the world over.

∞

So, How's The Sabbatical Going?

That's a question I've been hearing a lot this year, and understandably so. Most of my friends and my students have never experienced one. I hope that all of them have a chance to take a sabbatical someday so they can see for themselves what a gift it is. Since so many of my students wonder what I am doing when I'm not on campus, I'm writing this mostly for them. Many of them have (very sweetly!) told me they miss me. Let me assure them: it's mutual. But it has also been very good for me to take this year away from the classroom.

Sabbaticals and Long Service Leaves

By coincidence, a handful of my friends were on some sort of sabbatical last summer. Mostly they work for tech firms that recognize that sabbaticals make for more creative, more productive workers. One of them was enjoying a long service leave that Australian law mandates.

Most jobs in the United States don't offer sabbaticals, but I'm fortunate enough to have one that does. Sometimes my kids chide me for choosing a job with relatively low pay, but self-regulated time is something money can't easily buy. I think I chose my career pretty well.

I say "self-regulated time" because my sabbatical isn't early retirement or a long vacation. My job as a college professor has three basic components: teaching, scholarship, and service. A sabbatical frees me from the first of those components, and from parts of the third. More precisely, it frees me from the daily tasks of teaching and service, but I expect that at the end of this year I will be a better teacher because I've had time to do research and to tear down and rebuild some of my classes. And any college capable of taking the long view knows that faculty who take sabbaticals can render better service over the long haul.

What I've been doing

To the casual observer it probably looks like I've spent a lot of time in coffee shops and airports, and not much else. For the last three years I've devoted myself to teaching and service, giving only a little of my time to scholarship. So when I began my sabbatical my scholarly life felt like deep waters pent up behind a strained dam. Over the last few years I've sketched out five books and seven articles and book chapters. Over my sabbatical I hoped to get maybe one book and a couple of articles done. That may not sound like much, but it's fairly ambitious, given how much time it takes to do the research and to write well.

Since my job description breaks down into the three parts I mentioned above, let me say a few words about what I've been doing this year in each of those areas.

Writing: As for academic writing, so far, I've completed one book (on brook trout), and made significant progress on two others (both on the philosophy of religion). Once I get them done, books four and five are ready to go, too. I've submitted one book chapter for someone else's book, and I'm about to submit another. I've written a few book reviews for popular and scholarly journals, too. Last week I gave a lecture at the College of William and Mary on war and evil. Now I'm preparing that lecture for publication as a journal article. By the time this sabbatical is over, I hope to have at least one book under contract and two more articles sent off for review. I've also done some more popular writing, including a couple of articles on virtue ethics in the Chronicle of Higher Education's Chronicle Review - one on guns and one on the ethics of drones or UAVs. Perhaps most importantly, I've been writing every day. As you can see, I've been trying to write quickly here on this blog a couple of times a week, and I've been writing in a lot of other places as well. Like any other skill, it comes more fluidly with practice.

Teaching: I've also had the pleasure of planning some new classes, including one I plan to co-teach on environmental science and ecology, and a course for alumni I'll teach in Greece this summer with another Classics professor. And I have a whopping stack of books I've wanted to read that I've been devouring hungrily. When you're the professor, it's also good to be the student as often as possible.

Service: Even though I'm away from campus, my heart is still there. Everything I do as a professor winds up leaning back towards the classroom, which means towards my students. Nothing I do matters more than the people I do it with and for, I think. I must have written sixty letters of recommendation for students this year (which is more time-intensive than one might think). Sabbatical has also given me the chance to help some colleagues here and at other universities. I've been helping half a dozen friends who teach Classics, Philosophy, and Biology at other universities by reading and commenting on drafts of their essays and books. And I've done a lot of "double-blind" reviewing for six or seven academic publishers who want advice on whether to publish certain books or journal articles. Best of all has been time to collaborate with colleagues in far-off places, corresponding with professors and graduate students around the world about philosophy, ecology, Scriptural Reasoning, Henry Bugbee, Charles Peirce, C.S. Lewis, and other matters close to my heart. I list this as "service" but I could just as well call it "ways I've learned from other people far away."

But Have You Taken Some Time To Rest?

Yes. The word "sabbatical" has its roots in a Hebrew word, shabbath, meaning "to rest." It would be a shame not to use the time to get some rest. Last summer I spent two weeks in a writing retreat sponsored by Oregon State at their Shotpouch Creek Cabin with my friend and co-author Matthew Dickerson. We were working, but what restful work it can be to live, think, and write quietly with a friend. We spent half of each day writing, and the other half talking, hiking, fishing, wading in the ocean. We borrowed some hymnals from an Episcopal church in Eugene and spent part of each evening singing as the sun declined behind the coastal range.

On my way to Oregon, I drove my sons to the coast last summer to look at colleges, to go whale-watching, and to watch some professional soccer matches. When I got home to Sioux Falls, I joined a gym and I became my son's rec league soccer coach. This is his last year of living at home with us, and I can't tell you how grateful I am to have this time with him before adulthood takes him off on the next leg of his life's journey. Despite all the work, and travel, and writing, I've had more time with my wife and my kids, and more time for self-care. I feel much healthier and fitter now than I did a year ago. I have a feeling my family is better off for that, too.

I wish everyone, regardless of their line of work, could have an experience like this every few years. It might remind us all what matters. It's expensive, I know. I took a hefty pay cut from an already modest salary to have this year off, and thankfully our savings have been enough to get us through. (And writing and lecturing makes me a few extra ducats to send to my daughter in college from time to time or to spend on my boys at home.)

No doubt some people will read this and wonder why my college is willing to pay me anything at all when I'm not showing up to work. The answer is that some colleges still take the long view. You have to put aside your monthly planner and get a calendar that measures time and value "not by the times but by the eternities" (pace Thoreau), that looks down the years the way a carpenter holds a plank to her eye and looks down the full length of the board rather than seeing only the grain of what is nearest. Money has been spent on me this year by people who thought it worthwhile to let me stretch from my cramped pose. They have let me drink from distant streams so that I can come back nourished not just by the Big Sioux and the Missouri but by the waters of Oregon and New York and Virginia - and in some sense by the Hippocrene itself.

So that's what I've been doing. I'm sorry I haven't been around campus much. In the long run, what I've been doing should make my return to campus a very good one indeed. I can't wait to tell you more about what I've learned this year once I return.

Sabbaticals and Long Service Leaves

|

| Sabbaticals can be seasons of letting dry husks bear new life. |

Most jobs in the United States don't offer sabbaticals, but I'm fortunate enough to have one that does. Sometimes my kids chide me for choosing a job with relatively low pay, but self-regulated time is something money can't easily buy. I think I chose my career pretty well.

I say "self-regulated time" because my sabbatical isn't early retirement or a long vacation. My job as a college professor has three basic components: teaching, scholarship, and service. A sabbatical frees me from the first of those components, and from parts of the third. More precisely, it frees me from the daily tasks of teaching and service, but I expect that at the end of this year I will be a better teacher because I've had time to do research and to tear down and rebuild some of my classes. And any college capable of taking the long view knows that faculty who take sabbaticals can render better service over the long haul.

What I've been doing

To the casual observer it probably looks like I've spent a lot of time in coffee shops and airports, and not much else. For the last three years I've devoted myself to teaching and service, giving only a little of my time to scholarship. So when I began my sabbatical my scholarly life felt like deep waters pent up behind a strained dam. Over the last few years I've sketched out five books and seven articles and book chapters. Over my sabbatical I hoped to get maybe one book and a couple of articles done. That may not sound like much, but it's fairly ambitious, given how much time it takes to do the research and to write well.

Since my job description breaks down into the three parts I mentioned above, let me say a few words about what I've been doing this year in each of those areas.

Writing: As for academic writing, so far, I've completed one book (on brook trout), and made significant progress on two others (both on the philosophy of religion). Once I get them done, books four and five are ready to go, too. I've submitted one book chapter for someone else's book, and I'm about to submit another. I've written a few book reviews for popular and scholarly journals, too. Last week I gave a lecture at the College of William and Mary on war and evil. Now I'm preparing that lecture for publication as a journal article. By the time this sabbatical is over, I hope to have at least one book under contract and two more articles sent off for review. I've also done some more popular writing, including a couple of articles on virtue ethics in the Chronicle of Higher Education's Chronicle Review - one on guns and one on the ethics of drones or UAVs. Perhaps most importantly, I've been writing every day. As you can see, I've been trying to write quickly here on this blog a couple of times a week, and I've been writing in a lot of other places as well. Like any other skill, it comes more fluidly with practice.

| ||

| Snail shells grow by slow accumulation, as habits do. |

Service: Even though I'm away from campus, my heart is still there. Everything I do as a professor winds up leaning back towards the classroom, which means towards my students. Nothing I do matters more than the people I do it with and for, I think. I must have written sixty letters of recommendation for students this year (which is more time-intensive than one might think). Sabbatical has also given me the chance to help some colleagues here and at other universities. I've been helping half a dozen friends who teach Classics, Philosophy, and Biology at other universities by reading and commenting on drafts of their essays and books. And I've done a lot of "double-blind" reviewing for six or seven academic publishers who want advice on whether to publish certain books or journal articles. Best of all has been time to collaborate with colleagues in far-off places, corresponding with professors and graduate students around the world about philosophy, ecology, Scriptural Reasoning, Henry Bugbee, Charles Peirce, C.S. Lewis, and other matters close to my heart. I list this as "service" but I could just as well call it "ways I've learned from other people far away."

|

| The license plate on the rental car I had at a recent conference. |

Yes. The word "sabbatical" has its roots in a Hebrew word, shabbath, meaning "to rest." It would be a shame not to use the time to get some rest. Last summer I spent two weeks in a writing retreat sponsored by Oregon State at their Shotpouch Creek Cabin with my friend and co-author Matthew Dickerson. We were working, but what restful work it can be to live, think, and write quietly with a friend. We spent half of each day writing, and the other half talking, hiking, fishing, wading in the ocean. We borrowed some hymnals from an Episcopal church in Eugene and spent part of each evening singing as the sun declined behind the coastal range.

On my way to Oregon, I drove my sons to the coast last summer to look at colleges, to go whale-watching, and to watch some professional soccer matches. When I got home to Sioux Falls, I joined a gym and I became my son's rec league soccer coach. This is his last year of living at home with us, and I can't tell you how grateful I am to have this time with him before adulthood takes him off on the next leg of his life's journey. Despite all the work, and travel, and writing, I've had more time with my wife and my kids, and more time for self-care. I feel much healthier and fitter now than I did a year ago. I have a feeling my family is better off for that, too.

I wish everyone, regardless of their line of work, could have an experience like this every few years. It might remind us all what matters. It's expensive, I know. I took a hefty pay cut from an already modest salary to have this year off, and thankfully our savings have been enough to get us through. (And writing and lecturing makes me a few extra ducats to send to my daughter in college from time to time or to spend on my boys at home.)

No doubt some people will read this and wonder why my college is willing to pay me anything at all when I'm not showing up to work. The answer is that some colleges still take the long view. You have to put aside your monthly planner and get a calendar that measures time and value "not by the times but by the eternities" (pace Thoreau), that looks down the years the way a carpenter holds a plank to her eye and looks down the full length of the board rather than seeing only the grain of what is nearest. Money has been spent on me this year by people who thought it worthwhile to let me stretch from my cramped pose. They have let me drink from distant streams so that I can come back nourished not just by the Big Sioux and the Missouri but by the waters of Oregon and New York and Virginia - and in some sense by the Hippocrene itself.

So that's what I've been doing. I'm sorry I haven't been around campus much. In the long run, what I've been doing should make my return to campus a very good one indeed. I can't wait to tell you more about what I've learned this year once I return.

∞

Writing, Law, and Memory in Ancient Gortyn

In the ruins of Gortyn, in central Crete, some of the famous ancient laws of Crete are preserved in stone. Archaeologists uncovered them in 1884, and have since built a brick enclosure to protect them from the weather.

Even though I'm not an expert in the Doric dialect, I love to read this inscription, for several reasons that might interest even those who don't know Greek.

First of all, it has an unusual alphabet, containing fewer letters than modern or classical Attic Greek. It lacks the vowels eta and omega (for which it uses epsilon and omicron), and the consonants zeta, xi, phi, chi, and psi (for which it substitutes other letters or combinations of other letters: two deltas for zeta, kappa+sigma for xi; pi for phi; kappa for chi; pi+sigma for psi.)

It also uses a letter that has since fallen out of use, the digamma. The digamma (or wau) is probably related to the Hebrew letter waw (or vav) and to the Roman letter F, which it closely resembles. By the classical age it had dropped out of use in Greek, and is fairly rare, like the letters sampi and qoppa.

(There is also a digamma in Delphi, not far from the Athena Pronaia sanctuary, on an upright stone dedicated to Athenai Warganai. That second word is related to the Greek word for "work" or "deed," ergon, and also to our word "work." This stone, pictured below, evinces several peculiarities of archaic Greek script. Look at the second word, which looks like it says FARCANAI. The first letter is digamma; the third letter, rho, very much resembles the Latin "R"; the letter immediately after it, gamma, looks like a flattened upper-case "C.")

Second, the writing is in boustrophedon style. Boustrophedon means something like "as the ox turns." Today we write in stoichedon style, in which all the letters face the same direction, like soldiers standing in formation. Boustrophedon is based on an agricultural, not a military ideal: the writer writes as a farmer plows. Write to the end of the line, and then, rather than returning to the left side of the page, turn the letters to face the opposite direction and write from right to left. When you read boustrophedon, your eye follows a zig-zag across the page -- or the stone.

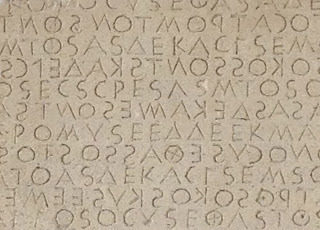

Have a look at this close-up of the engraving at Gortys and look at the way letters like "E," "K," and "S" face in adjacent lines:

(By the way, that "S" character is actually an iota; sigmas look like this: M; mu is like our "M" with an extra stroke added.)

There are a lot of other reasons to like this place, and this inscription, but I'll limit myself to just one more thing for now: memory.

This inscription is one way that an ancient community deliberately remembered their laws. They wrote down what they decided, and that has affected our lives. Writing the law down makes it accessible to everyone, and makes judicial decisions transparent. It establishes a set of expectations for conduct in the community, and makes those expectations known even to aliens.

The code at Gortyn records (in Column IX, around the middle, if you're curious) the presence at court of someone in addition to the judge: the mnemon. You can see by the word's resemblance to our word "mnemonic" that it has to do with memory. The mnemon's job was to act as a witness to previous judicial decisions, and to remember them and remind the judge of those decisions. The mnemon's job was not to decide cases but to be a kind of embodiment of the law and therefore an embodiment of fairness.

Unfortunately, no mnemon lives forever. Presumably, the writing on the wall at Gortyn was a way of preserving what mattered most in the court, so that when they passed away, their memories would live on through the ages.

*****

Harold Fowler writes in a footnote to his 1921 translation of the Cratylus that under Eucleides the Athenians officially changed their alphabet from the archaic one to the Ionian alphabet in 404/403 BCE. This expanded their system of vowels, adding the long vowels eta and omega. It became known as the Euclidean Alphabet.

*****

If you can find it, Adonis Vasilakis' The Great Inscription of the Law Code of Gortyn (Heraklion/Iraklio: Mystis O.E.) is a great resource. It has a facsimile of the whole wall, a complete translation, and some helpful historical observations. ISBN 9608853400

|

| Gortyn, Crete |

Even though I'm not an expert in the Doric dialect, I love to read this inscription, for several reasons that might interest even those who don't know Greek.

First of all, it has an unusual alphabet, containing fewer letters than modern or classical Attic Greek. It lacks the vowels eta and omega (for which it uses epsilon and omicron), and the consonants zeta, xi, phi, chi, and psi (for which it substitutes other letters or combinations of other letters: two deltas for zeta, kappa+sigma for xi; pi for phi; kappa for chi; pi+sigma for psi.)

It also uses a letter that has since fallen out of use, the digamma. The digamma (or wau) is probably related to the Hebrew letter waw (or vav) and to the Roman letter F, which it closely resembles. By the classical age it had dropped out of use in Greek, and is fairly rare, like the letters sampi and qoppa.

(There is also a digamma in Delphi, not far from the Athena Pronaia sanctuary, on an upright stone dedicated to Athenai Warganai. That second word is related to the Greek word for "work" or "deed," ergon, and also to our word "work." This stone, pictured below, evinces several peculiarities of archaic Greek script. Look at the second word, which looks like it says FARCANAI. The first letter is digamma; the third letter, rho, very much resembles the Latin "R"; the letter immediately after it, gamma, looks like a flattened upper-case "C.")

|

|

"Athenai Warganai" inscription at Delphi

|

Second, the writing is in boustrophedon style. Boustrophedon means something like "as the ox turns." Today we write in stoichedon style, in which all the letters face the same direction, like soldiers standing in formation. Boustrophedon is based on an agricultural, not a military ideal: the writer writes as a farmer plows. Write to the end of the line, and then, rather than returning to the left side of the page, turn the letters to face the opposite direction and write from right to left. When you read boustrophedon, your eye follows a zig-zag across the page -- or the stone.

Have a look at this close-up of the engraving at Gortys and look at the way letters like "E," "K," and "S" face in adjacent lines:

|

| Close-up of the Gortyn Code |

There are a lot of other reasons to like this place, and this inscription, but I'll limit myself to just one more thing for now: memory.

This inscription is one way that an ancient community deliberately remembered their laws. They wrote down what they decided, and that has affected our lives. Writing the law down makes it accessible to everyone, and makes judicial decisions transparent. It establishes a set of expectations for conduct in the community, and makes those expectations known even to aliens.

The code at Gortyn records (in Column IX, around the middle, if you're curious) the presence at court of someone in addition to the judge: the mnemon. You can see by the word's resemblance to our word "mnemonic" that it has to do with memory. The mnemon's job was to act as a witness to previous judicial decisions, and to remember them and remind the judge of those decisions. The mnemon's job was not to decide cases but to be a kind of embodiment of the law and therefore an embodiment of fairness.

Unfortunately, no mnemon lives forever. Presumably, the writing on the wall at Gortyn was a way of preserving what mattered most in the court, so that when they passed away, their memories would live on through the ages.

|

| National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Possibly a child's dish? The sixth letter is digamma. |

*****

Harold Fowler writes in a footnote to his 1921 translation of the Cratylus that under Eucleides the Athenians officially changed their alphabet from the archaic one to the Ionian alphabet in 404/403 BCE. This expanded their system of vowels, adding the long vowels eta and omega. It became known as the Euclidean Alphabet.

*****

If you can find it, Adonis Vasilakis' The Great Inscription of the Law Code of Gortyn (Heraklion/Iraklio: Mystis O.E.) is a great resource. It has a facsimile of the whole wall, a complete translation, and some helpful historical observations. ISBN 9608853400

∞

This year I am playing around with Google Wave's map feature and wondering if I can use Wave to help prepare my students to make the most of our limited time in Greece.

Do you have suggestions for how I can use this for my course? Are you also new to Wave and interested in Greece? If so, send me a wave at dr.dlohara@googlewave.com and I'll include you in my "sandbox" where I'm playing around with the possibilities.

(Photo credit: Dr. Jeffrey A. Johnson, Providence College)

Google Wave and My Course in Greece

Each year I teach a course in Greece, and I require my students to make presentations at a variety of archaeological and cultural sites.

This year I am playing around with Google Wave's map feature and wondering if I can use Wave to help prepare my students to make the most of our limited time in Greece.

Do you have suggestions for how I can use this for my course? Are you also new to Wave and interested in Greece? If so, send me a wave at dr.dlohara@googlewave.com and I'll include you in my "sandbox" where I'm playing around with the possibilities.

(Photo credit: Dr. Jeffrey A. Johnson, Providence College)