Greek

∞

Of Men and of Angels

"If I speak with the tongues of men and of angels, but I have not love, then I have become a resounding gong or a clanging cymbal."

That's from one of St. Paul's letters to the church in Corinth. It's a passage often read at weddings, probably because it speaks eloquently about agapic love.

I like it for another reason: it has a nice onomatopoeic pun in the Greek text. Paul's "If I speak..." is lalo; his "clanging" is alaladzon, which sounds like the noise a gong makes and sounds like it could mean "un-speaking." (In Greek, words that begin with "a-" are often like English words beginning with "un-".)

This week, as we approach the third Sunday in Advent, I was looking again at a poem I wrote during this week a few years ago, after the school shooting in Newtown. In it I compared first responders and teachers and others who give up so much for the sake of the common good to angels. That is my second-most read post ever.

The most-read post is one I wrote after Ferguson, about the militarization of our first responders, and the way the tools we equip ourselves with change the way we interact with the world - and with other people.

Both of these posts are about public servants. Taken together they remind me that what is done in love can be heroic and life-giving, and what is done in fear can become tyrannical. They remind me that we have a tendency to revere the outward signs of badges and uniforms, when we should judge characters by the habits they embody and by the actions that show the habits.

And they remind me that we have a long, long way to go before we can say we have learned to love one another.

*****

I should add that even the title to this post is misleading. The word Paul uses is not "men" but "humans." I like the cadence of the old translation "men" but the word is anthropon, not andron. Normally I prefer the more inclusive (and more accurate) "humans" but I first learned this verse in an older, poetic translation and the rhythm of it has stuck with me.

That's from one of St. Paul's letters to the church in Corinth. It's a passage often read at weddings, probably because it speaks eloquently about agapic love.

I like it for another reason: it has a nice onomatopoeic pun in the Greek text. Paul's "If I speak..." is lalo; his "clanging" is alaladzon, which sounds like the noise a gong makes and sounds like it could mean "un-speaking." (In Greek, words that begin with "a-" are often like English words beginning with "un-".)

This week, as we approach the third Sunday in Advent, I was looking again at a poem I wrote during this week a few years ago, after the school shooting in Newtown. In it I compared first responders and teachers and others who give up so much for the sake of the common good to angels. That is my second-most read post ever.

The most-read post is one I wrote after Ferguson, about the militarization of our first responders, and the way the tools we equip ourselves with change the way we interact with the world - and with other people.

Both of these posts are about public servants. Taken together they remind me that what is done in love can be heroic and life-giving, and what is done in fear can become tyrannical. They remind me that we have a tendency to revere the outward signs of badges and uniforms, when we should judge characters by the habits they embody and by the actions that show the habits.

And they remind me that we have a long, long way to go before we can say we have learned to love one another.

*****

I should add that even the title to this post is misleading. The word Paul uses is not "men" but "humans." I like the cadence of the old translation "men" but the word is anthropon, not andron. Normally I prefer the more inclusive (and more accurate) "humans" but I first learned this verse in an older, poetic translation and the rhythm of it has stuck with me.

∞

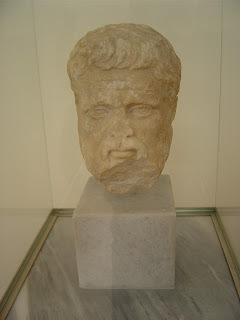

Demosthenes' "Against Meidias"

Tonight I am reading Demosthenes' Against Meidias. Why? Because nothing prevents me from doing so, and books like this repay the reader many times over for the little effort it takes to read them.

The text is full of citations of Athenian law, and both its structure and content tell us a great deal about ancient jurisprudence.

Demosthenes also gives us some gems of ancient legal reasoning, reminding us that there is very little new under the sun. For instance: Meidias, a wealthy and brutish man, assaulted Demosthenes while Demosthenes was performing a sacred state function. Meidias then claimed that such assaults happen all the time, and therefore his was unimportant. Demosthenes replied that the decision of the court will affect not only this single case but that it will have the effect of deterring future assaults as well.

But on this reading I am especially enjoying Demosthenes as a handbook of erudite Attic insults. His repeated epithet against Euctemon, Ευκτημων ο κονιορτος, "dust-raising Euctemon" or "Dirty old Euctemon" is a minor example.

A far better one is this one, aimed at Meidias:

The text is full of citations of Athenian law, and both its structure and content tell us a great deal about ancient jurisprudence.

Demosthenes also gives us some gems of ancient legal reasoning, reminding us that there is very little new under the sun. For instance: Meidias, a wealthy and brutish man, assaulted Demosthenes while Demosthenes was performing a sacred state function. Meidias then claimed that such assaults happen all the time, and therefore his was unimportant. Demosthenes replied that the decision of the court will affect not only this single case but that it will have the effect of deterring future assaults as well.

But on this reading I am especially enjoying Demosthenes as a handbook of erudite Attic insults. His repeated epithet against Euctemon, Ευκτημων ο κονιορτος, "dust-raising Euctemon" or "Dirty old Euctemon" is a minor example.

A far better one is this one, aimed at Meidias:

“If, men of Athens, public service consists in saying to you at all the meetings of the Assembly and on every possible occasion, ‘We are the men who perform the public services; we are those who advance your tax-money; we are the capitalists” – if that is all it means, then I confess that Meidias has shown himself the most distinguished citizen of Athens.” (Section 153; Taken from the Loeb edition. J.H. Vince, Trans. (Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1956) p.107)He hardly needs to say what follows: of course, public service consists in much more than that, and by offering these public rebukes against a man like this I am fulfilling one of my highest duties. Powerful people who use their power to abuse their fellow citizens deserve no less.

∞

Written On The Skin

One of the peculiar things about teaching Greek and knowing several other ancient languages is that people often come to me seeking help with tattoos.

A few years ago a student named Brian came to me and asked "How do you say 'Suck Less' in Greek?" Apparently this was a phrase that his running coach said to his team to inspire them to run better.

As crude as the phrase is, I was intrigued by the problem of translation. "In order to translate the phrase I'd have to know what you mean by it," I replied. I spent a little while explaining how it would be possible to say, for instance, that an infant should nurse less; or that one should inhale less strongly. Or, if you pursue the more colloquial usage of the verb "suck," you might decide that it refers to poor behavior or - ahem - to a kind of erotic pleasure-giving in which the giver is thought to be demeaned by the giving.

Eventually I made the case that if you want to say it in Classical Greek, it would make sense to say it in a way that attended to the use of words in that language, and pointed him to Plutarch's Sayings of Spartan Women as a source of pithy sayings about living and acting strenuously. Ever since I took my first Greek class with Eve Adler at Middlebury College years ago, I've liked the phrase η ταν η επι τας, (at the link above, see #16 under "Other Spartan Women"; click on the Greek flag to see the full Greek text) which is often translated "Come back with your shield or upon it," meaning "Act virtuously in battle; either die with your weapons or win with your weapons, but do not throw them away in order to win your life at the expense of your virtue." I like the Greek phrase for its Laconian pithiness.

Of course, that one didn't quite make sense for a runner, so I showed him another from the same collection, κατα βημα της αρετης μεμνησο, or "With every step, remember [your] virtue." ("Virtue" is not a perfect translation; you could translate it as "excellence" also.)

Three years have passed since that conversation with Brian, but a few months ago he tracked me down and showed me his tattoo, which I rather like:

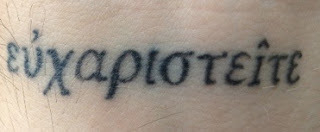

In a new twist, last year another student asked me to help him find the Greek verb "give thanks" as it appears in I Thessalonians 5.18. He didn't tell me what he planned to do with it, but when I saw him later that year at a wedding he showed me this, which he has tattooed on his wrist:

The word you see is ευχαριστειτε, related to our word "Eucharist" and the modern Greek ευχαριστω, meaning "I thank you."

I say this is a "new twist" because at least one passage in the Hebrew scriptures (Leviticus 19.28) appears to prohibit tattooing one's skin. Getting a tattoo, and in particular getting a tattoo of scripture, offers a bit of insight into one's hermeneutics. If the Gospels prohibited tattoos, I doubt many Christians would get them, but since the prohibition comes in the Hebrew scriptures, and since it seems to be tied to particular practices of worship or enslavement that no longer seem relevant, many young Christians are untroubled by it.

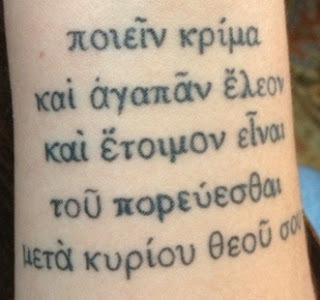

Recently one of my advisees showed me one of several tattoos she has recently acquired. This one is a longer Biblical text, from the prophet Micah, chapter 6, verse 8. I thought it interesting that she chose to get the Septuagint Greek rather than the Hebrew. She knows and translates Biblical (Koine) Greek and so I suppose she felt closer to that language. The text below means "...to do justice and to love mercy and to be ready/zealous to walk humbly with the Lord your God."

I like that verse quite a lot. If you don't know it, it begins by saying that this is what God asks of people. It's the sort of description that makes religion sound less like a burden and more like a description of a life well-lived.

I'm always reluctant to give advice about tattoos, because they're so permanent and so personal. And when I do give advice, I always want to write footnotes about regional dialects and historical and textual variants, or about the difficulties of translation. Quotes out of their native context so often seem lonely to me - such is my academic habit, of always seeing texts as living and moving and having their being* in nests and webs of other texts. Perhaps that's why I've never been inked myself, and I doubt I ever will get a "tat." I'm just not confident I've found words or an image that I'd want written on me forever. Sometimes that feels virtuous because it's prudent; other times I wonder if that's not a moral failing on my part, like I should be willing to commit to something. But I think for now I will remain uninked, and will continue to admire the commitments of my students.

* For example: I am borrowing this phrase ("live and move and have their being") from St Paul in Acts 17.28; he, in turn, appears to be borrowing it from Epimenides, who writes Εν αυτω γαρ ζωμεν και κινουμεθα και εσμεν. The phrase winds up being used in a number of other places, having been so eloquently translated into English by the King James Version of the Bible. See, for example, its use in the Book of Common Prayer, and in the first line of the hymn "We Come O Christ To Thee."

A few years ago a student named Brian came to me and asked "How do you say 'Suck Less' in Greek?" Apparently this was a phrase that his running coach said to his team to inspire them to run better.

As crude as the phrase is, I was intrigued by the problem of translation. "In order to translate the phrase I'd have to know what you mean by it," I replied. I spent a little while explaining how it would be possible to say, for instance, that an infant should nurse less; or that one should inhale less strongly. Or, if you pursue the more colloquial usage of the verb "suck," you might decide that it refers to poor behavior or - ahem - to a kind of erotic pleasure-giving in which the giver is thought to be demeaned by the giving.

Eventually I made the case that if you want to say it in Classical Greek, it would make sense to say it in a way that attended to the use of words in that language, and pointed him to Plutarch's Sayings of Spartan Women as a source of pithy sayings about living and acting strenuously. Ever since I took my first Greek class with Eve Adler at Middlebury College years ago, I've liked the phrase η ταν η επι τας, (at the link above, see #16 under "Other Spartan Women"; click on the Greek flag to see the full Greek text) which is often translated "Come back with your shield or upon it," meaning "Act virtuously in battle; either die with your weapons or win with your weapons, but do not throw them away in order to win your life at the expense of your virtue." I like the Greek phrase for its Laconian pithiness.

Of course, that one didn't quite make sense for a runner, so I showed him another from the same collection, κατα βημα της αρετης μεμνησο, or "With every step, remember [your] virtue." ("Virtue" is not a perfect translation; you could translate it as "excellence" also.)

Three years have passed since that conversation with Brian, but a few months ago he tracked me down and showed me his tattoo, which I rather like:

In a new twist, last year another student asked me to help him find the Greek verb "give thanks" as it appears in I Thessalonians 5.18. He didn't tell me what he planned to do with it, but when I saw him later that year at a wedding he showed me this, which he has tattooed on his wrist:

The word you see is ευχαριστειτε, related to our word "Eucharist" and the modern Greek ευχαριστω, meaning "I thank you."

I say this is a "new twist" because at least one passage in the Hebrew scriptures (Leviticus 19.28) appears to prohibit tattooing one's skin. Getting a tattoo, and in particular getting a tattoo of scripture, offers a bit of insight into one's hermeneutics. If the Gospels prohibited tattoos, I doubt many Christians would get them, but since the prohibition comes in the Hebrew scriptures, and since it seems to be tied to particular practices of worship or enslavement that no longer seem relevant, many young Christians are untroubled by it.

Recently one of my advisees showed me one of several tattoos she has recently acquired. This one is a longer Biblical text, from the prophet Micah, chapter 6, verse 8. I thought it interesting that she chose to get the Septuagint Greek rather than the Hebrew. She knows and translates Biblical (Koine) Greek and so I suppose she felt closer to that language. The text below means "...to do justice and to love mercy and to be ready/zealous to walk humbly with the Lord your God."

I like that verse quite a lot. If you don't know it, it begins by saying that this is what God asks of people. It's the sort of description that makes religion sound less like a burden and more like a description of a life well-lived.

I'm always reluctant to give advice about tattoos, because they're so permanent and so personal. And when I do give advice, I always want to write footnotes about regional dialects and historical and textual variants, or about the difficulties of translation. Quotes out of their native context so often seem lonely to me - such is my academic habit, of always seeing texts as living and moving and having their being* in nests and webs of other texts. Perhaps that's why I've never been inked myself, and I doubt I ever will get a "tat." I'm just not confident I've found words or an image that I'd want written on me forever. Sometimes that feels virtuous because it's prudent; other times I wonder if that's not a moral failing on my part, like I should be willing to commit to something. But I think for now I will remain uninked, and will continue to admire the commitments of my students.

*****

* For example: I am borrowing this phrase ("live and move and have their being") from St Paul in Acts 17.28; he, in turn, appears to be borrowing it from Epimenides, who writes Εν αυτω γαρ ζωμεν και κινουμεθα και εσμεν. The phrase winds up being used in a number of other places, having been so eloquently translated into English by the King James Version of the Bible. See, for example, its use in the Book of Common Prayer, and in the first line of the hymn "We Come O Christ To Thee."

*****

Update: a week or so after posting this I ran into the mother of one of the people whose tattoos are shown above. She thanked me, though I am not sure whether she was thanking me for helping her son get a tattoo, or for helping him to get the grammar right.

∞

Writing, Law, and Memory in Ancient Gortyn

In the ruins of Gortyn, in central Crete, some of the famous ancient laws of Crete are preserved in stone. Archaeologists uncovered them in 1884, and have since built a brick enclosure to protect them from the weather.

Even though I'm not an expert in the Doric dialect, I love to read this inscription, for several reasons that might interest even those who don't know Greek.

First of all, it has an unusual alphabet, containing fewer letters than modern or classical Attic Greek. It lacks the vowels eta and omega (for which it uses epsilon and omicron), and the consonants zeta, xi, phi, chi, and psi (for which it substitutes other letters or combinations of other letters: two deltas for zeta, kappa+sigma for xi; pi for phi; kappa for chi; pi+sigma for psi.)

It also uses a letter that has since fallen out of use, the digamma. The digamma (or wau) is probably related to the Hebrew letter waw (or vav) and to the Roman letter F, which it closely resembles. By the classical age it had dropped out of use in Greek, and is fairly rare, like the letters sampi and qoppa.

(There is also a digamma in Delphi, not far from the Athena Pronaia sanctuary, on an upright stone dedicated to Athenai Warganai. That second word is related to the Greek word for "work" or "deed," ergon, and also to our word "work." This stone, pictured below, evinces several peculiarities of archaic Greek script. Look at the second word, which looks like it says FARCANAI. The first letter is digamma; the third letter, rho, very much resembles the Latin "R"; the letter immediately after it, gamma, looks like a flattened upper-case "C.")

Second, the writing is in boustrophedon style. Boustrophedon means something like "as the ox turns." Today we write in stoichedon style, in which all the letters face the same direction, like soldiers standing in formation. Boustrophedon is based on an agricultural, not a military ideal: the writer writes as a farmer plows. Write to the end of the line, and then, rather than returning to the left side of the page, turn the letters to face the opposite direction and write from right to left. When you read boustrophedon, your eye follows a zig-zag across the page -- or the stone.

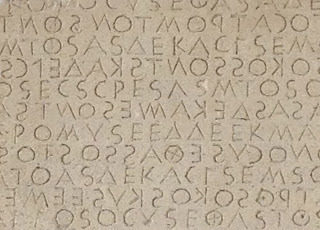

Have a look at this close-up of the engraving at Gortys and look at the way letters like "E," "K," and "S" face in adjacent lines:

(By the way, that "S" character is actually an iota; sigmas look like this: M; mu is like our "M" with an extra stroke added.)

There are a lot of other reasons to like this place, and this inscription, but I'll limit myself to just one more thing for now: memory.

This inscription is one way that an ancient community deliberately remembered their laws. They wrote down what they decided, and that has affected our lives. Writing the law down makes it accessible to everyone, and makes judicial decisions transparent. It establishes a set of expectations for conduct in the community, and makes those expectations known even to aliens.

The code at Gortyn records (in Column IX, around the middle, if you're curious) the presence at court of someone in addition to the judge: the mnemon. You can see by the word's resemblance to our word "mnemonic" that it has to do with memory. The mnemon's job was to act as a witness to previous judicial decisions, and to remember them and remind the judge of those decisions. The mnemon's job was not to decide cases but to be a kind of embodiment of the law and therefore an embodiment of fairness.

Unfortunately, no mnemon lives forever. Presumably, the writing on the wall at Gortyn was a way of preserving what mattered most in the court, so that when they passed away, their memories would live on through the ages.

*****

Harold Fowler writes in a footnote to his 1921 translation of the Cratylus that under Eucleides the Athenians officially changed their alphabet from the archaic one to the Ionian alphabet in 404/403 BCE. This expanded their system of vowels, adding the long vowels eta and omega. It became known as the Euclidean Alphabet.

*****

If you can find it, Adonis Vasilakis' The Great Inscription of the Law Code of Gortyn (Heraklion/Iraklio: Mystis O.E.) is a great resource. It has a facsimile of the whole wall, a complete translation, and some helpful historical observations. ISBN 9608853400

|

| Gortyn, Crete |

Even though I'm not an expert in the Doric dialect, I love to read this inscription, for several reasons that might interest even those who don't know Greek.

First of all, it has an unusual alphabet, containing fewer letters than modern or classical Attic Greek. It lacks the vowels eta and omega (for which it uses epsilon and omicron), and the consonants zeta, xi, phi, chi, and psi (for which it substitutes other letters or combinations of other letters: two deltas for zeta, kappa+sigma for xi; pi for phi; kappa for chi; pi+sigma for psi.)

It also uses a letter that has since fallen out of use, the digamma. The digamma (or wau) is probably related to the Hebrew letter waw (or vav) and to the Roman letter F, which it closely resembles. By the classical age it had dropped out of use in Greek, and is fairly rare, like the letters sampi and qoppa.

(There is also a digamma in Delphi, not far from the Athena Pronaia sanctuary, on an upright stone dedicated to Athenai Warganai. That second word is related to the Greek word for "work" or "deed," ergon, and also to our word "work." This stone, pictured below, evinces several peculiarities of archaic Greek script. Look at the second word, which looks like it says FARCANAI. The first letter is digamma; the third letter, rho, very much resembles the Latin "R"; the letter immediately after it, gamma, looks like a flattened upper-case "C.")

|

|

"Athenai Warganai" inscription at Delphi

|

Second, the writing is in boustrophedon style. Boustrophedon means something like "as the ox turns." Today we write in stoichedon style, in which all the letters face the same direction, like soldiers standing in formation. Boustrophedon is based on an agricultural, not a military ideal: the writer writes as a farmer plows. Write to the end of the line, and then, rather than returning to the left side of the page, turn the letters to face the opposite direction and write from right to left. When you read boustrophedon, your eye follows a zig-zag across the page -- or the stone.

Have a look at this close-up of the engraving at Gortys and look at the way letters like "E," "K," and "S" face in adjacent lines:

|

| Close-up of the Gortyn Code |

There are a lot of other reasons to like this place, and this inscription, but I'll limit myself to just one more thing for now: memory.

This inscription is one way that an ancient community deliberately remembered their laws. They wrote down what they decided, and that has affected our lives. Writing the law down makes it accessible to everyone, and makes judicial decisions transparent. It establishes a set of expectations for conduct in the community, and makes those expectations known even to aliens.

The code at Gortyn records (in Column IX, around the middle, if you're curious) the presence at court of someone in addition to the judge: the mnemon. You can see by the word's resemblance to our word "mnemonic" that it has to do with memory. The mnemon's job was to act as a witness to previous judicial decisions, and to remember them and remind the judge of those decisions. The mnemon's job was not to decide cases but to be a kind of embodiment of the law and therefore an embodiment of fairness.

Unfortunately, no mnemon lives forever. Presumably, the writing on the wall at Gortyn was a way of preserving what mattered most in the court, so that when they passed away, their memories would live on through the ages.

|

| National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Possibly a child's dish? The sixth letter is digamma. |

*****

Harold Fowler writes in a footnote to his 1921 translation of the Cratylus that under Eucleides the Athenians officially changed their alphabet from the archaic one to the Ionian alphabet in 404/403 BCE. This expanded their system of vowels, adding the long vowels eta and omega. It became known as the Euclidean Alphabet.

*****

If you can find it, Adonis Vasilakis' The Great Inscription of the Law Code of Gortyn (Heraklion/Iraklio: Mystis O.E.) is a great resource. It has a facsimile of the whole wall, a complete translation, and some helpful historical observations. ISBN 9608853400

∞

"I Know That I Don't Know"?

If you stroll through the Plaka tourist district in Athens, you'll have ample opportunities to buy t-shirts and other items with the slogan "en oida oti ouden oida," most of which will attribute this saying to Socrates. It means "I know this one thing: that I know nothing."

Of course, it is a little silly and possibly self-contradictory, since knowing one thing means knowing something, while knowing nothing precludes knowing something.

Still, if Socrates said it, it's worth repeating, right? (For kicks, Google it and see how many times it is quoted authoritatively.)

But I wonder if Socrates ever said it at all.

Yes, I know that we don't know exactly what Socrates said. Socrates left us no writings, and as for transcriptions of his conversations, we have only three first-hand sources to rely on: those of Plato and Xenophon his students, and of Aristophanes his ostensible rival. It seems likely that Aristophanes did not attempt to represent Socrates accurately, nor as a philosopher. Plato may well have invented much of Socrates' dialogue as well, but he also had a stake in continuing and defending the philosophical work of Socrates in Athens.

For this reason, when philosophers refer to Socrates, we are usually referring to the Socrates found in Plato's rather extensive writings.

So did Plato's Socrates ever say "en oida oti ouden oida"? It appears not.

The closest thing I've found is a passage in Plato's Apology of Socrates, where Socrates says something that should really be translated as something like this: I do not claim to know those things that I do not know.

This is not only more reasonable, it's also good advice: don't pretend to know what you don't know and you'll avoid a lot of trouble.

It's important for another reason, though. The "en oida oti ouden oida" quote seems to be something of a staple of frosh philosophy texts and classes.

The danger here is that we will present an ancient philosopher (two of them, in this case) as though he were fairly foolish; and as a result, we will not take ancient philosophy seriously.

All it should take to cure this is a quick look at the Greek text of any of Plato's dialogues. The Phaedo, for instance, bears a slow and careful read in Greek, since no translation I've found captures all the wordplay. And as Peirce pointed out, when one reads the Greek, one discovers something else that the translators often veil from our sight: Plato's Socrates uses the language of syllogism in a way that shows that he was doing Aristotelian logic before Aristotle was.

By relying on hearsay rather than on engagement with the primary texts, we close off a path of inquiry into a whole set of ancient philosophical texts. "Doesn't their being ancient mean that they are exhausted?" you may ask. Old trees, it seems to me, may still bear rich fruit. And just as we find that old caves sometimes have rich troves of ancient unread texts, what else might we find if we take the time to read the ancients closely?

Of course, it is a little silly and possibly self-contradictory, since knowing one thing means knowing something, while knowing nothing precludes knowing something.

Still, if Socrates said it, it's worth repeating, right? (For kicks, Google it and see how many times it is quoted authoritatively.)

But I wonder if Socrates ever said it at all.

Yes, I know that we don't know exactly what Socrates said. Socrates left us no writings, and as for transcriptions of his conversations, we have only three first-hand sources to rely on: those of Plato and Xenophon his students, and of Aristophanes his ostensible rival. It seems likely that Aristophanes did not attempt to represent Socrates accurately, nor as a philosopher. Plato may well have invented much of Socrates' dialogue as well, but he also had a stake in continuing and defending the philosophical work of Socrates in Athens.

For this reason, when philosophers refer to Socrates, we are usually referring to the Socrates found in Plato's rather extensive writings.

So did Plato's Socrates ever say "en oida oti ouden oida"? It appears not.

The closest thing I've found is a passage in Plato's Apology of Socrates, where Socrates says something that should really be translated as something like this: I do not claim to know those things that I do not know.

This is not only more reasonable, it's also good advice: don't pretend to know what you don't know and you'll avoid a lot of trouble.

It's important for another reason, though. The "en oida oti ouden oida" quote seems to be something of a staple of frosh philosophy texts and classes.

The danger here is that we will present an ancient philosopher (two of them, in this case) as though he were fairly foolish; and as a result, we will not take ancient philosophy seriously.

All it should take to cure this is a quick look at the Greek text of any of Plato's dialogues. The Phaedo, for instance, bears a slow and careful read in Greek, since no translation I've found captures all the wordplay. And as Peirce pointed out, when one reads the Greek, one discovers something else that the translators often veil from our sight: Plato's Socrates uses the language of syllogism in a way that shows that he was doing Aristotelian logic before Aristotle was.

By relying on hearsay rather than on engagement with the primary texts, we close off a path of inquiry into a whole set of ancient philosophical texts. "Doesn't their being ancient mean that they are exhausted?" you may ask. Old trees, it seems to me, may still bear rich fruit. And just as we find that old caves sometimes have rich troves of ancient unread texts, what else might we find if we take the time to read the ancients closely?