heart

∞

Hid In My Heart

Before my friend's father died, he had a stroke that left him mostly without words for a few weeks. His near-total aphasia left little intact, but there were some words that came out readily. My friend's dad had been a pastor, and when his faculty of speech left him, the words of his prayers, of the scriptures, and of the hymns and psalms were all that remained. Daily habit of repetition had ingrained them in his heart, too deep to be erased by the stroke.

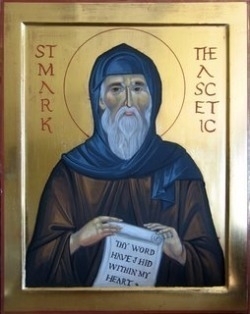

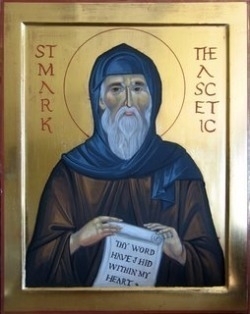

On his blog, Kelly Dean Jolley has an icon of St Mark the Ascetic, or St Mark the Wrestler, that Jolley has kindly allowed me to include here. In his hands St Mark holds a scroll that reads "Thy word have I hid within my heart." Those words are from the 119th Psalm, a long poem about scripture.

When I was in college, my French professor Charles Nunley required me to memorize a new poem every week. Every week or two I'd go to his office and he would name one of the poems I'd learned and expect me to recite it, and then to discuss it. I'm not a great memorizer, so it was painful work, but I've been grateful for the discipline every year since then. It is a gift to have verses hidden in my heart.

When I was in college, my French professor Charles Nunley required me to memorize a new poem every week. Every week or two I'd go to his office and he would name one of the poems I'd learned and expect me to recite it, and then to discuss it. I'm not a great memorizer, so it was painful work, but I've been grateful for the discipline every year since then. It is a gift to have verses hidden in my heart.

I am reminded of Mary, the mother of Jesus, when she heard what the shepherds were saying. Luke tells us that she "treasured these things in her heart," which I take to mean that she heard them, and then put them in that front room of her memory, the palm and fingertips of the mind where we touch and explore and consider ideas, turning them over and over again.

Well, this is what I do with treasured verses, anyway. Like I said, I'm a poor memorizer. But when I work at it, I hold the verses at mind's-eye level and gaze at them, running my inner eye down the length of them repeatedly, considering the way the grain moves and feeling the heft of the words until the grooves of my mind fit the notches of the words like a key. Because I hope that what I have hid in my heart will be like the Brothers Grimm's "Golden Key," which opens...well, I had better not tell you. Read it for yourself.

I wonder - when the great grinding erasure of time scrubs away at my memories, what will be left? What grooves in my grain will be too deep to scrape away? What treasures, what verses, what songs of my species will be buried too deep in my heart for the thief of time to steal?

On his blog, Kelly Dean Jolley has an icon of St Mark the Ascetic, or St Mark the Wrestler, that Jolley has kindly allowed me to include here. In his hands St Mark holds a scroll that reads "Thy word have I hid within my heart." Those words are from the 119th Psalm, a long poem about scripture.

When I was in college, my French professor Charles Nunley required me to memorize a new poem every week. Every week or two I'd go to his office and he would name one of the poems I'd learned and expect me to recite it, and then to discuss it. I'm not a great memorizer, so it was painful work, but I've been grateful for the discipline every year since then. It is a gift to have verses hidden in my heart.

When I was in college, my French professor Charles Nunley required me to memorize a new poem every week. Every week or two I'd go to his office and he would name one of the poems I'd learned and expect me to recite it, and then to discuss it. I'm not a great memorizer, so it was painful work, but I've been grateful for the discipline every year since then. It is a gift to have verses hidden in my heart.I am reminded of Mary, the mother of Jesus, when she heard what the shepherds were saying. Luke tells us that she "treasured these things in her heart," which I take to mean that she heard them, and then put them in that front room of her memory, the palm and fingertips of the mind where we touch and explore and consider ideas, turning them over and over again.

Well, this is what I do with treasured verses, anyway. Like I said, I'm a poor memorizer. But when I work at it, I hold the verses at mind's-eye level and gaze at them, running my inner eye down the length of them repeatedly, considering the way the grain moves and feeling the heft of the words until the grooves of my mind fit the notches of the words like a key. Because I hope that what I have hid in my heart will be like the Brothers Grimm's "Golden Key," which opens...well, I had better not tell you. Read it for yourself.

I wonder - when the great grinding erasure of time scrubs away at my memories, what will be left? What grooves in my grain will be too deep to scrape away? What treasures, what verses, what songs of my species will be buried too deep in my heart for the thief of time to steal?

∞

Perpetual Motion

As the sun sets it sends its last rays shooting up from below the horizon to illuminate the undersides of contrails, the warp and weft of high-altitude aircraft that have crushed the air before them and left a trail of disturbance behind to mark their racing progress.

I myself am a frequent traveler. My far-flung family and my work as an educator, writer, and lecturer mean I am often in airports. At those times, I am mostly concerned with making my next flight. But when I gaze at the evening sky from my kitchen window and see the silver lines glowing over the setting sun, I wonder: where are we going? And why are we in such a hurry to get there?

Mise En Place

I recently read an interview with Scott Russell Sanders in the Englewood Review of Books. In it Sanders talks about the virtue of living in one place for a long time, of "Staying Put."

We Americans seem to be constantly on the move. We began as a nation of movers, and we have filled a continent by our frenetic motion.

When I took the job I currently have, my wife and I were moving to a part of the world we'd never even visited, the prairies of the upper midwest. We knew nobody here, had no roots here. We left our home and friends and family to find work, and we thought it would be a temporary assignment, a sojourn from which we would return to the place where we, like seeds from a tree, first fell to earth.

Little by little I am coming to think I am not on a sojourn here but am a transplant.

Taproots

I long for the mountains and clear streams of my youth. But when I think of myself as a temporary resident, I find it harder to put down taproots that can drink deeply from the waters that flow far underground.

The danger? Plants with shallow roots cannot weather droughts as well as those with deep roots. By analogy, as we commit ourselves to the place we live in, the more strength we can draw from that place.

And plants with taproots are good for the soil, too. They break the hard clay and bore holes into which the rain can sink deeply. Behold the lowly dandelion, the maker of topsoil. If I sink roots here, I'll make it more likely that my community will benefit from my presence.

This sinking of roots is hard to do. It can be hard because the culture may be different, for instance. Eight years into this gig, I still struggle with midwestern indirect communication, and with the very, very slow process of getting to know native midwesterners.

Weaving Our Hearts

Of course, being surrounded by others who are also on the move makes it hard, too. When I was in grad school one of our neighbors, Lisa, told us she could not be our friend because she knew we were only there for five years. We shared a backyard, and our children played together, but Lisa knew that too many times she had allowed her roots to grow into the lives of other mobile academics, and when they were uprooted, so was her heart. It hurt to hear her tell us that, but who could blame her?

And it is hard for me not to be near mountains. Sometimes, gazing out that kitchen window in the summertime I see great thunderheads low on the western horizon, gathering strength as they roll across the prairie towards Sioux Falls. My heart so longs for the mountains that nearly every time I see those thunderclouds I let myself believe for an instant that they are solid mountains, not ephemeral, gauzy clouds. I would sooner believe in a cataclysmic upheaval of the earth than believe I am without mountains forever.

Sometimes people here try to comfort me by telling me that here, in this same state, we have the Black Hills. I know they mean well, and I know it's a point of pride for them, but those mountains are over three hundred and fifty miles away. I cannot see them from here, and for some reason, that matters. It's like telling a hungry person to take heart, because somewhere else, somewhere not here, there is a banquet. It only makes the pangs sharper.

The Mountains Underground

My heart leans towards the mountains, but for today - the only day I have any control over, and a limited control, at that - I am trying to turn my feet into roots.

Years ago, when I was working in Poland, a friend brought me to a place called Tarnowska Góra. There's a silver mine under fairly flat ground there. Knowing that góra means "mountain," I asked her "Gdzie jest góra? Where is the mountain?" She smiled, and pointed down at her feet. "Underground," she said.

This is the image I am trying to cultivate: here there are mountains, too, but like the hidden thoughts of coy midwesterners, they are concealed by the superficial appearances.

These mountains under the prairie are not the Adirondacks of New York, or the bold Catskills fringing the Hudson River, whose heights cannot be avoided. They are not the Sangre de Cristo mountains or the Green Mountains or the Alleghenies, each of which have been my home, places where my children were born and raised. These subterranean mountains wait quietly beneath, supporting all things evenly, deeply rooted, immovable. I cannot gauge their height with my eye; I must measure it patiently, with my feet, by walking the slow prairie, by standing still. And, perhaps, though my heart is not yet ready to accept it, by letting my body one day be buried here, adding my small mass to these mountains, raising them incrementally by the simple height of my dormant bones.

But that is for another day. Today, I will walk, and let my feet learn to feel the mountains below.

All The Mountains Are Underground Here

|

| Sunset over the Yellowstone River |

As the sun sets it sends its last rays shooting up from below the horizon to illuminate the undersides of contrails, the warp and weft of high-altitude aircraft that have crushed the air before them and left a trail of disturbance behind to mark their racing progress.

I myself am a frequent traveler. My far-flung family and my work as an educator, writer, and lecturer mean I am often in airports. At those times, I am mostly concerned with making my next flight. But when I gaze at the evening sky from my kitchen window and see the silver lines glowing over the setting sun, I wonder: where are we going? And why are we in such a hurry to get there?

Mise En Place

I recently read an interview with Scott Russell Sanders in the Englewood Review of Books. In it Sanders talks about the virtue of living in one place for a long time, of "Staying Put."

We Americans seem to be constantly on the move. We began as a nation of movers, and we have filled a continent by our frenetic motion.

When I took the job I currently have, my wife and I were moving to a part of the world we'd never even visited, the prairies of the upper midwest. We knew nobody here, had no roots here. We left our home and friends and family to find work, and we thought it would be a temporary assignment, a sojourn from which we would return to the place where we, like seeds from a tree, first fell to earth.

Little by little I am coming to think I am not on a sojourn here but am a transplant.

Taproots

I long for the mountains and clear streams of my youth. But when I think of myself as a temporary resident, I find it harder to put down taproots that can drink deeply from the waters that flow far underground.

The danger? Plants with shallow roots cannot weather droughts as well as those with deep roots. By analogy, as we commit ourselves to the place we live in, the more strength we can draw from that place.

And plants with taproots are good for the soil, too. They break the hard clay and bore holes into which the rain can sink deeply. Behold the lowly dandelion, the maker of topsoil. If I sink roots here, I'll make it more likely that my community will benefit from my presence.

This sinking of roots is hard to do. It can be hard because the culture may be different, for instance. Eight years into this gig, I still struggle with midwestern indirect communication, and with the very, very slow process of getting to know native midwesterners.

Weaving Our Hearts

Of course, being surrounded by others who are also on the move makes it hard, too. When I was in grad school one of our neighbors, Lisa, told us she could not be our friend because she knew we were only there for five years. We shared a backyard, and our children played together, but Lisa knew that too many times she had allowed her roots to grow into the lives of other mobile academics, and when they were uprooted, so was her heart. It hurt to hear her tell us that, but who could blame her?

And it is hard for me not to be near mountains. Sometimes, gazing out that kitchen window in the summertime I see great thunderheads low on the western horizon, gathering strength as they roll across the prairie towards Sioux Falls. My heart so longs for the mountains that nearly every time I see those thunderclouds I let myself believe for an instant that they are solid mountains, not ephemeral, gauzy clouds. I would sooner believe in a cataclysmic upheaval of the earth than believe I am without mountains forever.

Sometimes people here try to comfort me by telling me that here, in this same state, we have the Black Hills. I know they mean well, and I know it's a point of pride for them, but those mountains are over three hundred and fifty miles away. I cannot see them from here, and for some reason, that matters. It's like telling a hungry person to take heart, because somewhere else, somewhere not here, there is a banquet. It only makes the pangs sharper.

The Mountains Underground

My heart leans towards the mountains, but for today - the only day I have any control over, and a limited control, at that - I am trying to turn my feet into roots.

|

| A picture of my heart: my boys, and mountains beneath them. |

Years ago, when I was working in Poland, a friend brought me to a place called Tarnowska Góra. There's a silver mine under fairly flat ground there. Knowing that góra means "mountain," I asked her "Gdzie jest góra? Where is the mountain?" She smiled, and pointed down at her feet. "Underground," she said.

This is the image I am trying to cultivate: here there are mountains, too, but like the hidden thoughts of coy midwesterners, they are concealed by the superficial appearances.

These mountains under the prairie are not the Adirondacks of New York, or the bold Catskills fringing the Hudson River, whose heights cannot be avoided. They are not the Sangre de Cristo mountains or the Green Mountains or the Alleghenies, each of which have been my home, places where my children were born and raised. These subterranean mountains wait quietly beneath, supporting all things evenly, deeply rooted, immovable. I cannot gauge their height with my eye; I must measure it patiently, with my feet, by walking the slow prairie, by standing still. And, perhaps, though my heart is not yet ready to accept it, by letting my body one day be buried here, adding my small mass to these mountains, raising them incrementally by the simple height of my dormant bones.

But that is for another day. Today, I will walk, and let my feet learn to feel the mountains below.

∞

The standard view of logic was that all premises in logic were either derived from other syllogisms, or from authority. Since syllogisms are made up of premises, it must follow that if we trace our arguments back far enough, all our beliefs must ultimately rest on some authority. This would seem to prove that those who maintain the religious authority are best suited to resolve disputes.

Berengar argued, in his disputation with Lanfranc, that it is through the use of our reason that we imitate God and, in that imitation, are maintained and made new in that image. In simpler terms, if you believe you were made by God, then use the mind God gave you. Dialectic - reason in conversation with itself or with others - is a divinely-given place of refuge from error and confusion. This doesn't mean reason can't go awry; it's just a reminder that giving up on reasoning is not as pious as it might seem at first.

Scientia Cordis

Bear with me for a moment while I speak in Latin. This is a passage Charles Peirce cites in several places:

"Maximi plane cordis est, per omnia ad dialecticum confugere, quia confugere ad eam ad rationem est confugere, quo qui non confugit, cum secundum rationem sit factus ad imaginem Dei, suum honorem reliquit, nec potest renovari de die in diem ad imaginem Dei."

"Maximi plane cordis est, per omnia ad dialecticum confugere, quia confugere ad eam ad rationem est confugere, quo qui non confugit, cum secundum rationem sit factus ad imaginem Dei, suum honorem reliquit, nec potest renovari de die in diem ad imaginem Dei."

Berengar, De Sacra Caena. Cited in Charles Peirce, Collected Papers, 1.30. From "The Spirit of Scholasticism," in the first of his 1869 Harvard lectures. Peirce also cites this passage in his essay entitled "Questions Concerning Certain Faculties Claimed For Man."

For Peirce, the genius of Berengar (or Berengarius) lay in pointing out that authority itself must rest on reason, a view that must have seemed "opinionated, impious, and absurd" in his day. (Peirce, Collected Papers, 5.215)(My quick translation: "Clearly it is [a characteristic] of the greatest kind of heart always to seek refuge in dialectic, for to seek refuge in dialectic is to seek refuge in reason; so whoever does not seek that refuge - having been made in the image of God according to reason - abandons his honor, and cannot be renewed from day to day in God's image.")

The standard view of logic was that all premises in logic were either derived from other syllogisms, or from authority. Since syllogisms are made up of premises, it must follow that if we trace our arguments back far enough, all our beliefs must ultimately rest on some authority. This would seem to prove that those who maintain the religious authority are best suited to resolve disputes.

Berengar argued, in his disputation with Lanfranc, that it is through the use of our reason that we imitate God and, in that imitation, are maintained and made new in that image. In simpler terms, if you believe you were made by God, then use the mind God gave you. Dialectic - reason in conversation with itself or with others - is a divinely-given place of refuge from error and confusion. This doesn't mean reason can't go awry; it's just a reminder that giving up on reasoning is not as pious as it might seem at first.

∞

Peirce's Parable of the Puritan

Peirce once wrote a school-essay responding to a prompt that asked whether there was any valid excuse for the intolerance of the "Pilgrim Fathers." (MS 1633) Peirce replied with a parable, which I will paraphrase here:

On judgment day, a Puritan was called before God to give account of his life. The Puritan admitted his faults, and then pulled from his breast pocket a document that he claimed contained a justification of "hard-heartedness." When he handed this to God, someone laughed aloud at the possibility of making such a justification. The scoffer was seized by angels and taken to kneel before God, where "he will be told by the Judge that He considered it worthwhile to see what the Puritan had to say. But that he the scoffer as he judged shall be judged."

On judgment day, a Puritan was called before God to give account of his life. The Puritan admitted his faults, and then pulled from his breast pocket a document that he claimed contained a justification of "hard-heartedness." When he handed this to God, someone laughed aloud at the possibility of making such a justification. The scoffer was seized by angels and taken to kneel before God, where "he will be told by the Judge that He considered it worthwhile to see what the Puritan had to say. But that he the scoffer as he judged shall be judged."

∞

Scientia Cordis

"Let us not pretend to doubt in philosophy what we do not doubt in our hearts."

-- Charles Peirce, "Some Consequences of Four Incapacities," (1868).

-- Charles Peirce, "Some Consequences of Four Incapacities," (1868).