Hope

∞

We can begin by directing more funding to universities. We need bright engineers who have the freedom and funds to investigate how to make more efficient solar and wind energy.

We also need bright students in the humanities who will help us form the best policies to make sure we use our technology well. After all, a democracy can live without engineers, but it cannot survive long without reporters, teachers, and lawyers.

We know that money spent on education pays a perpetual dividend to both the person educated and her whole community.

We can also encourage the creation of new and important prizes. Why should we not have more prizes like the Nobel Prizes? And why shouldn't such a proud and wealthy nation fund some of those prizes? You've got the ear of the world for a little while longer. Use that opportunity well, and urge us to put our private funds into prizes for people who advance the causes that matter most to humanity: growing good food, creating and preserving clean water, protecting the species God told us to care for, healing the sick, liberating captives, and making us better producers and consumers of energy.

I am grateful for people who willingly take on the burdens of public office. I don't imagine it is easy. You remain in my prayers.

David

Hope And The Future: An Open Letter To The President

Dear President Obama,

I know you've got a lot on your mind right now, and I don't envy you the burdens of your office. I pray for you often, asking God to give you the wisdom to make good decisions and the strength to carry them out.

I have two requests for you today. The first is, please don't give up on hope. In your first campaign you spoke about hope a lot, and I think you know that meant a lot to people everywhere. We all want hope, especially hope that we feel we can believe in. We will often settle for unreasonable hopes, but we prefer hopes that seem grounded in possibility rather than in wild fantasy. For a while there you sounded like you had both hope and reason for hope. When I think about the office you occupy, I imagine there's a lot that works to rein hope in, to tame hope and to break it. You start out with big ideals, and then everyone reminds you that limited resources will be made to seem even scarcer by partisan quarrels until there's nothing left to spend on dreams. But let me tell you this: we need you to make lots of small decisions, but we also need some big dreams, some reasonable hopes. We need someone who will climb the steps to the bully pulpit and preach a sermon that reminds us of "the better angels of our nature." Don't just make the little decisions; remind us of the great hopes that have lived in our nation.

I have two requests for you today. The first is, please don't give up on hope. In your first campaign you spoke about hope a lot, and I think you know that meant a lot to people everywhere. We all want hope, especially hope that we feel we can believe in. We will often settle for unreasonable hopes, but we prefer hopes that seem grounded in possibility rather than in wild fantasy. For a while there you sounded like you had both hope and reason for hope. When I think about the office you occupy, I imagine there's a lot that works to rein hope in, to tame hope and to break it. You start out with big ideals, and then everyone reminds you that limited resources will be made to seem even scarcer by partisan quarrels until there's nothing left to spend on dreams. But let me tell you this: we need you to make lots of small decisions, but we also need some big dreams, some reasonable hopes. We need someone who will climb the steps to the bully pulpit and preach a sermon that reminds us of "the better angels of our nature." Don't just make the little decisions; remind us of the great hopes that have lived in our nation.

The second request is related to the first: I'd like you to help us to nurture the reasonable hope that we can find new ways of making energy. There are powerful sermons being preached about building more oil and tar sand pipelines so that the old ways can be maintained. But those are sermons without hope, the sermons of a creed doomed to perish in fire and smoke of its own burning, the platitudes born of a faith in a limited and dwindling resource. They are the cynical homilies of those who pass the collection plate and who think the worst thing they can lose is our regular tithing to the god of petroleum.

We need a reformation in that way of thinking.

Because national security is not just about defending ourselves with bullets and bombs, and it's not just about making sure we have enough oil. In the long run, national security has to mean that we have taken good care of the land, so that it is still worth inhabiting. That, in turn, means we have nurtured our hearts and minds and cultivated our virtue. What, after all, does it profit a nation to gain the world and lose its soul? We are a nation of innovators, not just custodians of the status quo. We began as an experiment, and it is in experimentation and new thinking that our hope now lies.

I know you've got a lot on your mind right now, and I don't envy you the burdens of your office. I pray for you often, asking God to give you the wisdom to make good decisions and the strength to carry them out.

I have two requests for you today. The first is, please don't give up on hope. In your first campaign you spoke about hope a lot, and I think you know that meant a lot to people everywhere. We all want hope, especially hope that we feel we can believe in. We will often settle for unreasonable hopes, but we prefer hopes that seem grounded in possibility rather than in wild fantasy. For a while there you sounded like you had both hope and reason for hope. When I think about the office you occupy, I imagine there's a lot that works to rein hope in, to tame hope and to break it. You start out with big ideals, and then everyone reminds you that limited resources will be made to seem even scarcer by partisan quarrels until there's nothing left to spend on dreams. But let me tell you this: we need you to make lots of small decisions, but we also need some big dreams, some reasonable hopes. We need someone who will climb the steps to the bully pulpit and preach a sermon that reminds us of "the better angels of our nature." Don't just make the little decisions; remind us of the great hopes that have lived in our nation.

I have two requests for you today. The first is, please don't give up on hope. In your first campaign you spoke about hope a lot, and I think you know that meant a lot to people everywhere. We all want hope, especially hope that we feel we can believe in. We will often settle for unreasonable hopes, but we prefer hopes that seem grounded in possibility rather than in wild fantasy. For a while there you sounded like you had both hope and reason for hope. When I think about the office you occupy, I imagine there's a lot that works to rein hope in, to tame hope and to break it. You start out with big ideals, and then everyone reminds you that limited resources will be made to seem even scarcer by partisan quarrels until there's nothing left to spend on dreams. But let me tell you this: we need you to make lots of small decisions, but we also need some big dreams, some reasonable hopes. We need someone who will climb the steps to the bully pulpit and preach a sermon that reminds us of "the better angels of our nature." Don't just make the little decisions; remind us of the great hopes that have lived in our nation.The second request is related to the first: I'd like you to help us to nurture the reasonable hope that we can find new ways of making energy. There are powerful sermons being preached about building more oil and tar sand pipelines so that the old ways can be maintained. But those are sermons without hope, the sermons of a creed doomed to perish in fire and smoke of its own burning, the platitudes born of a faith in a limited and dwindling resource. They are the cynical homilies of those who pass the collection plate and who think the worst thing they can lose is our regular tithing to the god of petroleum.

We need a reformation in that way of thinking.

Because national security is not just about defending ourselves with bullets and bombs, and it's not just about making sure we have enough oil. In the long run, national security has to mean that we have taken good care of the land, so that it is still worth inhabiting. That, in turn, means we have nurtured our hearts and minds and cultivated our virtue. What, after all, does it profit a nation to gain the world and lose its soul? We are a nation of innovators, not just custodians of the status quo. We began as an experiment, and it is in experimentation and new thinking that our hope now lies.

We can begin by directing more funding to universities. We need bright engineers who have the freedom and funds to investigate how to make more efficient solar and wind energy.

We also need bright students in the humanities who will help us form the best policies to make sure we use our technology well. After all, a democracy can live without engineers, but it cannot survive long without reporters, teachers, and lawyers.

We know that money spent on education pays a perpetual dividend to both the person educated and her whole community.

We can also encourage the creation of new and important prizes. Why should we not have more prizes like the Nobel Prizes? And why shouldn't such a proud and wealthy nation fund some of those prizes? You've got the ear of the world for a little while longer. Use that opportunity well, and urge us to put our private funds into prizes for people who advance the causes that matter most to humanity: growing good food, creating and preserving clean water, protecting the species God told us to care for, healing the sick, liberating captives, and making us better producers and consumers of energy.

I am grateful for people who willingly take on the burdens of public office. I don't imagine it is easy. You remain in my prayers.

David

∞

Great Books, Pedagogy, and Hope

Great Books and the Great Conversation

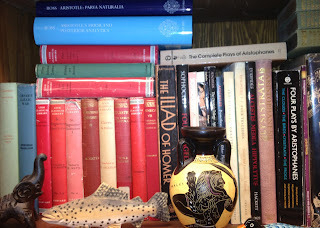

About fifteen years ago I enrolled in the "Great Books" M.A. program at St John's College in Santa Fe, New Mexico. It was one of the best decisions I've ever made.

Much as I appreciate my undergraduate education, too often it rewarded me for concealing my ignorance and emphasizing what I already knew. The problem, of course, is that my ignorance was thus shielded from the sterilizing sunlight of others' scrutiny and instruction.

Confessing Our Ignorance

Matthew Davis, my tutor and advisor at St John's, won me over to another way of viewing literature when, on one of the first days we met, he pointed to a passage in Plato's Republic and said "I have always wondered what Plato means by that." Looking up at the class, he asked, "Do any of you have any ideas about what he might be trying to say?"

Mr. Davis is the first professor I recall who openly confessed his ignorance, and who thereby modeled what it means to open oneself to the instruction of a great text. Not much has shaped my academic life as much as that.

Grappling With Classic Texts

As I have begun to mature into my own place as a teacher, I often think that this is the best thing I can give my students: not professorial and authoritative descriptions of texts, but an example of what it means to be a student. I can try to be an example of someone who sits with texts and listens to them, grappling with them, like Jacob with the angel or like Menelaus with Proteus: persistently grappling with my superior and refusing to let go until I receive a blessing. (Selah.)

For the last few years I have been seeking out and reading classic novels. As I read them I feel like an apprentice architect touring buildings, looking not just at the outward form and function but looking for the supporting structure, trying to notice the decisions the artist made about what to include and what to omit.

Along the way, I have begun trying to write bits of dialogue, scenes, characters, and other elements of fiction. I'm not trying to write a novel so much as trying to perform experiments the way high school science students do in labs: not to discover something new but to learn haptically, kinesthetically, experientially what the masters already know. I can't say that I've learned to write novels, so don't expect anything from me there. But as I've paid attention, I feel I've begun to squeeze some blessings out of the books, including some unexpected ones.

I've noticed, for instance, that Craig Nova writes about the olfactory sense in a way that makes me notice aromas I never noticed before. John Steinbeck has begun to make me care more about friendship, and about the people in front of me. Harold Frederic has me rethinking my early faith, and this is helping me look ahead as I try to nurture it into a faith worth having. Novels are helping me see the world differently.

So What Does This Have To Do With Hope?

I just finished Graham Greene's The Honorary Consul. Apparently this was Greene's favorite of his own works, and I can see why. Like many of the really good novels I've read, it has left me thinking about a range of topics, and longing for someone to talk about it with.

Which brings me to hope. I started reading Greene because Bill Swart, my friend and colleague, told me about how good Greene's novels are. Bill was right about this, so I sought him out the other day to talk more about Greene. We said too much to cover it all here, but Bill said something I can't bear not to repeat. When we began discussing Greene's The Power and the Glory, Bill said "That book gave me hope that my own self-perception might be wrong."

If you know the novel, you know why, because you know how Greene's characters wrestle with being both sinners and saints. If you don't know the novel, let me recommend it to you.

We Should Keep Teaching And Reading Fiction

I still have a lot to learn about novels. I doubt I'll ever write one - or a good one, anyway. But I'm delighting in reading them. Perhaps that's why they matter so much: they delight us, and capture us. When I'm in a good book I feel like I'm really in it. I stop seeing words on a page and start seeing, with some inner eye, the world the novelist sees.

And like all my other travels, journeys into fiction leave me a different person. I see different possibilities, I see -- and smell -- my world differently. I know it's important to teach young people to read non-fiction, but teaching fiction might be for them what The Power and the Glory was for Bill: a tonic for his soul, a sweet drink of hope that didn't just entertain, but that allowed him to envision his life, his work, and his purpose in an entirely new way.

About fifteen years ago I enrolled in the "Great Books" M.A. program at St John's College in Santa Fe, New Mexico. It was one of the best decisions I've ever made.

Much as I appreciate my undergraduate education, too often it rewarded me for concealing my ignorance and emphasizing what I already knew. The problem, of course, is that my ignorance was thus shielded from the sterilizing sunlight of others' scrutiny and instruction.

Confessing Our Ignorance

Matthew Davis, my tutor and advisor at St John's, won me over to another way of viewing literature when, on one of the first days we met, he pointed to a passage in Plato's Republic and said "I have always wondered what Plato means by that." Looking up at the class, he asked, "Do any of you have any ideas about what he might be trying to say?"

Mr. Davis is the first professor I recall who openly confessed his ignorance, and who thereby modeled what it means to open oneself to the instruction of a great text. Not much has shaped my academic life as much as that.

Grappling With Classic Texts

As I have begun to mature into my own place as a teacher, I often think that this is the best thing I can give my students: not professorial and authoritative descriptions of texts, but an example of what it means to be a student. I can try to be an example of someone who sits with texts and listens to them, grappling with them, like Jacob with the angel or like Menelaus with Proteus: persistently grappling with my superior and refusing to let go until I receive a blessing. (Selah.)

For the last few years I have been seeking out and reading classic novels. As I read them I feel like an apprentice architect touring buildings, looking not just at the outward form and function but looking for the supporting structure, trying to notice the decisions the artist made about what to include and what to omit.

Along the way, I have begun trying to write bits of dialogue, scenes, characters, and other elements of fiction. I'm not trying to write a novel so much as trying to perform experiments the way high school science students do in labs: not to discover something new but to learn haptically, kinesthetically, experientially what the masters already know. I can't say that I've learned to write novels, so don't expect anything from me there. But as I've paid attention, I feel I've begun to squeeze some blessings out of the books, including some unexpected ones.

I've noticed, for instance, that Craig Nova writes about the olfactory sense in a way that makes me notice aromas I never noticed before. John Steinbeck has begun to make me care more about friendship, and about the people in front of me. Harold Frederic has me rethinking my early faith, and this is helping me look ahead as I try to nurture it into a faith worth having. Novels are helping me see the world differently.

So What Does This Have To Do With Hope?

I just finished Graham Greene's The Honorary Consul. Apparently this was Greene's favorite of his own works, and I can see why. Like many of the really good novels I've read, it has left me thinking about a range of topics, and longing for someone to talk about it with.

Which brings me to hope. I started reading Greene because Bill Swart, my friend and colleague, told me about how good Greene's novels are. Bill was right about this, so I sought him out the other day to talk more about Greene. We said too much to cover it all here, but Bill said something I can't bear not to repeat. When we began discussing Greene's The Power and the Glory, Bill said "That book gave me hope that my own self-perception might be wrong."

If you know the novel, you know why, because you know how Greene's characters wrestle with being both sinners and saints. If you don't know the novel, let me recommend it to you.

We Should Keep Teaching And Reading Fiction

I still have a lot to learn about novels. I doubt I'll ever write one - or a good one, anyway. But I'm delighting in reading them. Perhaps that's why they matter so much: they delight us, and capture us. When I'm in a good book I feel like I'm really in it. I stop seeing words on a page and start seeing, with some inner eye, the world the novelist sees.

And like all my other travels, journeys into fiction leave me a different person. I see different possibilities, I see -- and smell -- my world differently. I know it's important to teach young people to read non-fiction, but teaching fiction might be for them what The Power and the Glory was for Bill: a tonic for his soul, a sweet drink of hope that didn't just entertain, but that allowed him to envision his life, his work, and his purpose in an entirely new way.

∞

Faith, Hope, and Certainty

“Certainty may be quite compatible with being at a loss to

say what one is certain of. Indeed

I seriously doubt if the notion of ‘certainty of,’ or ‘certainty that’ will

take us accurately to the heart of the matter. It seems to me that certainty is at least very much akin to

hope and faith. And I agree with

Gabriel Marcel that it would be a mistake to undertake the interpretation of

hope and of faith under what I will call the aspect of specificity, as if hope

were essentially ‘hope that,’ and faith ‘belief that.’ Likewise, then, of certainty: Perhaps

it too is not a matter of knowledge we can be said to possess.”

Henry Bugbee, The

Inward Morning, (Athens and London: University of Georgia Press, 1999),

pp.36-37.