hymns

- Forgive Onesimus, the indentured servant who ran away, breaking his contract with Philemon;

- Forgive Onesimus for stealing from Philemon as he fled;

- Welcome Onesimus back, not as a slave but as a family member.

∞

On Church Organs and Church Music

Recently I had the good fortune to hear an organ concert in Westminster Abbey. Not long afterwards I heard someone asking whether churches should get rid of their old organs. The question is a reasonable one, since organs are expensive to maintain, nigh impossible to move, and not many people can play them well. To those charges we should add the charge that organs are old-fashioned, and we are not.

I happen to love organ music, so that's one reason why I think we shouldn't get rid of the organs that remain in our churches. But there is at least one more important reason to think carefully about replacing them. Sometimes organs don't fit well with the buildings they are in, as though the organ was purchased on its own merits and not for the way it matched the acoustics of the building that holds it. In those cases, I don't see the loss if they're removed.

But this is a failing of architecture and economics, not just of music. The problem in that case is far greater than the sin of not being contemporary. An organ that does not match the church, or a church that is not made to be acoustically beautiful - both of these are failures, the kind of failure that comes from people who think that design and aesthetics are luxuries. But design is never neutral; it always helps or hurts. Efficiencies and economics can be the enemies of accomplishing the most worthwhile ends.

Here's what Westminster Abbey reminded me of: a well-built organ is not just an instrument; it is a part of the edifice itself. Specifically, it is the part that turns the whole edifice into a musical instrument. When the organ at Westminster is being played, it is not just a keyboard or pipes that are being played, but the whole building. Every bit of the building resounds. The music is not an isolated event anymore; the notes played and the place in which they are played have merged, and each reaches out to affirm the other. A good organ turns a church into a musical instrument.

Too often churches think of aesthetics last, if at all, or refuse to make aesthetics part of their theology. This is a huge mistake. The prophets describe the architectural adornments of the Ark and the Tabernacle and the Temple, giving those aesthetical elements a permanent place in Jewish and Christian canonical scripture. Similarly, the scriptures are full of songs and poems that - one could argue - are unnecessary to salvation. As Scott Parsons and I have argued, art and the sacred belong together. Our faith is not a matter of mere talk; sometimes what must be articulated cannot be said in words, but needs the smell of incense, the ringing of a sanctus bell, the deep bellow of a pipe organ, the beauty of light well-captured in glass or terrazzo.

If you're not sure of what I mean, listen to Árstí∂ir sing the medieval hymn Heyr himna smi∂ur -- in a train station. Can you imagine that being sung in a church with similar acoustics? Here's what I love about the video: when they sing that beautiful old song, everyone around them stops to listen. The beauty of the song is arresting, especially when it is paired with the building. What keeps us from dreaming of building churches, writing music, and designing instruments that could similarly arrest us?

I happen to love organ music, so that's one reason why I think we shouldn't get rid of the organs that remain in our churches. But there is at least one more important reason to think carefully about replacing them. Sometimes organs don't fit well with the buildings they are in, as though the organ was purchased on its own merits and not for the way it matched the acoustics of the building that holds it. In those cases, I don't see the loss if they're removed.

But this is a failing of architecture and economics, not just of music. The problem in that case is far greater than the sin of not being contemporary. An organ that does not match the church, or a church that is not made to be acoustically beautiful - both of these are failures, the kind of failure that comes from people who think that design and aesthetics are luxuries. But design is never neutral; it always helps or hurts. Efficiencies and economics can be the enemies of accomplishing the most worthwhile ends.

Here's what Westminster Abbey reminded me of: a well-built organ is not just an instrument; it is a part of the edifice itself. Specifically, it is the part that turns the whole edifice into a musical instrument. When the organ at Westminster is being played, it is not just a keyboard or pipes that are being played, but the whole building. Every bit of the building resounds. The music is not an isolated event anymore; the notes played and the place in which they are played have merged, and each reaches out to affirm the other. A good organ turns a church into a musical instrument.

Too often churches think of aesthetics last, if at all, or refuse to make aesthetics part of their theology. This is a huge mistake. The prophets describe the architectural adornments of the Ark and the Tabernacle and the Temple, giving those aesthetical elements a permanent place in Jewish and Christian canonical scripture. Similarly, the scriptures are full of songs and poems that - one could argue - are unnecessary to salvation. As Scott Parsons and I have argued, art and the sacred belong together. Our faith is not a matter of mere talk; sometimes what must be articulated cannot be said in words, but needs the smell of incense, the ringing of a sanctus bell, the deep bellow of a pipe organ, the beauty of light well-captured in glass or terrazzo.

[youtube=[www.youtube.com/watch](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e4dT8FJ2GE0&w=320&h=266])

If you're not sure of what I mean, listen to Árstí∂ir sing the medieval hymn Heyr himna smi∂ur -- in a train station. Can you imagine that being sung in a church with similar acoustics? Here's what I love about the video: when they sing that beautiful old song, everyone around them stops to listen. The beauty of the song is arresting, especially when it is paired with the building. What keeps us from dreaming of building churches, writing music, and designing instruments that could similarly arrest us?

∞

One thing that made the sermon especially strong was its open-endedness: our priest didn't try to apply the sermon to any one social problem, as he could have. Instead, he invited all his listeners to consider whether we'd be willing to have big love remake our lives. In other words, rather than making this into a doctrinal roll-call or a chance to affirm that we all believe the same thing and then move on, unchanged, we were invited to consider, in quiet self-examination, whether we were willing to let love rule in our lives.

One thing that made the sermon especially strong was its open-endedness: our priest didn't try to apply the sermon to any one social problem, as he could have. Instead, he invited all his listeners to consider whether we'd be willing to have big love remake our lives. In other words, rather than making this into a doctrinal roll-call or a chance to affirm that we all believe the same thing and then move on, unchanged, we were invited to consider, in quiet self-examination, whether we were willing to let love rule in our lives.

Part of me really doesn't like church. There's so much about it that bores me, and I usually like sermons least of all. And when I'm not bored, I'm often surrounded by people I don't know very well, shaking my hand and passing a sign of peace. It's an introvert-germophobe's introduction to the doctrine of hell, I guess, so it does serve that theological purpose. I'd prefer a quick nod, some formal bowing, a lot of incense and some well-tuned bells, but you can't always get what you want.

Part of me really doesn't like church. There's so much about it that bores me, and I usually like sermons least of all. And when I'm not bored, I'm often surrounded by people I don't know very well, shaking my hand and passing a sign of peace. It's an introvert-germophobe's introduction to the doctrine of hell, I guess, so it does serve that theological purpose. I'd prefer a quick nod, some formal bowing, a lot of incense and some well-tuned bells, but you can't always get what you want.

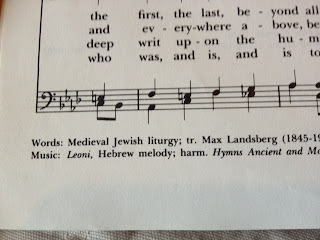

This morning was a pretty good morning. Not only did I hear that excellent sermon that will provide food for thought all week, we also sang a hymn that was translated from a Medieval Hebrew liturgy. Good hymnals and prayerbooks can be bouquets of the choicest flowers of religious poetry. The Book of Common Prayer has often rescued my anguished mind when it cannot find words. Often, when I sing hymns to the room-filling sound of a well-played pipe organ, I find myself wondering how people who do not have a congregation to sing with find opportunities to sing with others. That probably sounds judgmental, but I don't mean it to. I just wish there were more songs sung by people in our daily lives. I suspect the near-universal ownership of iPods is a result of the vanishing tradition of singing together.

This morning was a pretty good morning. Not only did I hear that excellent sermon that will provide food for thought all week, we also sang a hymn that was translated from a Medieval Hebrew liturgy. Good hymnals and prayerbooks can be bouquets of the choicest flowers of religious poetry. The Book of Common Prayer has often rescued my anguished mind when it cannot find words. Often, when I sing hymns to the room-filling sound of a well-played pipe organ, I find myself wondering how people who do not have a congregation to sing with find opportunities to sing with others. That probably sounds judgmental, but I don't mean it to. I just wish there were more songs sung by people in our daily lives. I suspect the near-universal ownership of iPods is a result of the vanishing tradition of singing together.

Can I Ask Questions In Church?

Today I heard a thoughtful, thought-provoking sermon about St Paul's Epistle to Philemon. The heart of it was this: Paul urged Philemon not to claim his legal right, but to lay aside his rights for the sake of the big love that wants to remodel his whole life.

Nobody in their right mind wants that.

Which is why Paul describes that big love elsewhere as foolishness to Greeks - and, he might have added, to anyone else who takes reason seriously.

After all, it's a little bit crazy to lay aside your legal rights for the sake of others. In Philemon's case, Paul was asking him to:

*****

One thing that made the sermon especially strong was its open-endedness: our priest didn't try to apply the sermon to any one social problem, as he could have. Instead, he invited all his listeners to consider whether we'd be willing to have big love remake our lives. In other words, rather than making this into a doctrinal roll-call or a chance to affirm that we all believe the same thing and then move on, unchanged, we were invited to consider, in quiet self-examination, whether we were willing to let love rule in our lives.

One thing that made the sermon especially strong was its open-endedness: our priest didn't try to apply the sermon to any one social problem, as he could have. Instead, he invited all his listeners to consider whether we'd be willing to have big love remake our lives. In other words, rather than making this into a doctrinal roll-call or a chance to affirm that we all believe the same thing and then move on, unchanged, we were invited to consider, in quiet self-examination, whether we were willing to let love rule in our lives.

This is like Mary's approach in John's Gospel, when she tells Jesus "They have no more wine," then tells the servants, "Do whatever he says." She knows enough to know that she doesn't know all the answers. I think our priest was saying something similar today: he doesn't know all the answers, but he's committed to big love, and was inviting us to consider whether we also share that confidence.

To put it differently, he left us with a question to mull over for the week.

Which is often far more helpful than being left with an answer.

*****

Part of me really doesn't like church. There's so much about it that bores me, and I usually like sermons least of all. And when I'm not bored, I'm often surrounded by people I don't know very well, shaking my hand and passing a sign of peace. It's an introvert-germophobe's introduction to the doctrine of hell, I guess, so it does serve that theological purpose. I'd prefer a quick nod, some formal bowing, a lot of incense and some well-tuned bells, but you can't always get what you want.

Part of me really doesn't like church. There's so much about it that bores me, and I usually like sermons least of all. And when I'm not bored, I'm often surrounded by people I don't know very well, shaking my hand and passing a sign of peace. It's an introvert-germophobe's introduction to the doctrine of hell, I guess, so it does serve that theological purpose. I'd prefer a quick nod, some formal bowing, a lot of incense and some well-tuned bells, but you can't always get what you want.

But you do often get what you need, and I think of church the way I think of prayer, or aerobic exercise, or dietary fiber: I need them. Even, and perhaps especially, when I don't want them. And when they are a part of my life, my life feels more whole.

This can be hard to explain to others, so I understand if you think I go to church because it makes me feel good, or because my culture has made it hard for me to think of doing otherwise, or because I feel guilty when I don't go.

I actually feel pretty good when I don't go to church, just like I feel pretty good when I decide to write a blog post instead of going on that four-mile run I had planned.

And so often, when I attend churches, I hear or see things I wish I hadn't heard or seen. These congregations founded on the worship of big love can become gardens overrun by the weeds of uncharitable hearts; some "hymns" I hear are schmaltzy or foolish, or unintentionally (I hope!) promote slavish and unkind ideas about race or gender. At times like that, I'm tempted to give up on "organized" religion altogether.

*****

This morning was a pretty good morning. Not only did I hear that excellent sermon that will provide food for thought all week, we also sang a hymn that was translated from a Medieval Hebrew liturgy. Good hymnals and prayerbooks can be bouquets of the choicest flowers of religious poetry. The Book of Common Prayer has often rescued my anguished mind when it cannot find words. Often, when I sing hymns to the room-filling sound of a well-played pipe organ, I find myself wondering how people who do not have a congregation to sing with find opportunities to sing with others. That probably sounds judgmental, but I don't mean it to. I just wish there were more songs sung by people in our daily lives. I suspect the near-universal ownership of iPods is a result of the vanishing tradition of singing together.

This morning was a pretty good morning. Not only did I hear that excellent sermon that will provide food for thought all week, we also sang a hymn that was translated from a Medieval Hebrew liturgy. Good hymnals and prayerbooks can be bouquets of the choicest flowers of religious poetry. The Book of Common Prayer has often rescued my anguished mind when it cannot find words. Often, when I sing hymns to the room-filling sound of a well-played pipe organ, I find myself wondering how people who do not have a congregation to sing with find opportunities to sing with others. That probably sounds judgmental, but I don't mean it to. I just wish there were more songs sung by people in our daily lives. I suspect the near-universal ownership of iPods is a result of the vanishing tradition of singing together.

When I came home I saw that a friend had tagged me in a post on Facebook, where she shared this article about the importance of continuing to ask big questions. To which I say "amen."

The article raises just this question of whether a decline in attendance at religious services decreases the places in which can we ask big questions:

The article raises just this question of whether a decline in attendance at religious services decreases the places in which can we ask big questions:

"“For anyone who goes to church, these are the questions they are essentially grappling with via their faith,” said Brooks. Indeed, a measurable drop in religious affiliation and attendance at houses of worship may be a factor in the decline of a culture of inquiry and conversation."

I don't know if that's true, and I don't want to claim that the sky is falling because the pews aren't full. But I do find that sitting in the pew helps me, and I think it could be more helpful to more people if there were more sermons like the one I heard today. It's good to ask questions together, and to let the questions do their work.

So I hope that more of us who think that meeting together to pray and sing and reflect on what we believe is a worthwhile practice will do as our priest did this morning, inviting others to turn with him to reflect on the big questions, and the big ideas, and the big love, that - in my case, at least - can keep us from living unexamined lives.