icons

∞

No Flash!

My job as a college professor brings me to a lot of museums and archives, and this summer has been especially full of visits to museums, historical sites, and archives in Greece, Norway, the U.K., and the U.S.

As a kid I found most museums boring, but now I really appreciate and enjoy them. I've spent many days of my life in the British Museum and in several museums in Athens, and each time I'm there I feel that time is rewarded with fresh discoveries and with reacquaintance with familiar objects.

Some museums have a reasonable policy of not permitting flash photography, since the bright light of camera flashes can degrade the colors of paint and dyes. Others must insist on no photography when the objects on display are on loan from owners who will not permit reproductions of their images.

But in general, I object when museums and archives prohibit photography, especially when the aim is to force more visitors to come to the physical site. Most people the world over will never be able to visit the world's great museums. And many scholars could benefit from digital images of archival materials. During a recent visit to an archive that hosts many of Henry David Thoreau's papers, I was disappointed to learn that I would not be permitted to take photos of some of the papers I wanted to read later. This forces scholars to spend more time in the archive, which means spending more money - simply prohibitive for many of us. So I type, or scribble, as quickly as I can to transcribe texts in some archives, and hope that I can somehow find what I need in the time I have.

The Ballpoint As A Tool For Seeing

But what if what you want to remember is not a text but an image? Scott Parsons, a gifted artist and a friend of mine, has taught me that one need not be very talented with a pen to begin to capture images. As Dr. Cornelius said in one of Lewis's stories, "A scholar is never without [pen and paper]," and I've tried to make that my rule, too, carrying pen and paper with me everywhere. Scott tells me that a cheap ballpoint pen is, after all, one of the best tools for seeing.

It turns out, he's right: the pen is often mightier than the camera. I think this is because the camera captures all available light, while the pen only captures what my eye and hand tell it to. The chief obstacle to overcome is the disconnect between what my eye sees and what my hand draws. Scott has pointed out to me that this is not the fault of my hand so much as a problem of mistaking what I think I see for what I actually see. In other words, it is a problem of misdirected attention, when I pay attention to what I think is there rather than to what the light is actually doing.

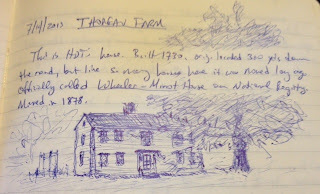

So far, no one in any museum has objected to my drawing what I see. In most cases, when I draw pictures, people seem honored that I should take the time. I drew this picture of the Thoreau homestead in Concord this summer, and a curator there happened to see it as I journaled. She seemed pleased that I took the time to try to draw it. I find that taking the time to draw helps me to notice details I'd have otherwise missed. You can see I'm not a great artist, little improved from my youth. But I'm not ashamed, because even if it's not a brilliant representation, it doesn't need to be; it is a record, in blue lines, of ten minutes of attention. The image is not a photograph; it is a symbol of memory, like a call number for a book in a library that helps me to recall quickly the time I spent sitting on the grass in Concord considering the place where Henry David grew up.

Memories Of Delight

I've also begun drawing inside people's homes when I'm a guest there - always with permission, of course. This summer several kind Norwegian friends took me in for a week, giving me space to write while overlooking a fjord, and cooking me delicious Norwegian food. In the evening we built fires in the hearth and talked quietly or played cards. These are fond memories with friends, but they're also memories of delight in seeing new shapes of things. Norwegians build fires and eat waffles as we Americans do, but the fireplaces and the waffle irons are different from the ones I know from my home. The waffles I saw were all shaped like heart-flowers, giving visual delight in addition to the delightful taste (though I'm not yet sold on brown cheese as a topping.) The fireplaces I saw were all open on not just one side, but two. They looked different, but it was only when I began to draw them that I noticed what I was seeing. This is a small thing, perhaps, but it is a reminder that what I take to be the natural shape of things often has as much to do with the traditions I grew up with as with nature. As an aside, when I take the time to draw pictures, it often seems to be taken as a sign of respect, which is just how I intend it: this place you live in, this object in your home, is so wonderful to me that I wish to give it my attention and make it a permanent resident in my journal, the log-book of my heart. May I? Thank you, and thank you for the hospitality that allowed me to witness this.

Pics Or It Didn't Happen

Sometimes I choose not to take photos simply because the camera is itself a sign. When we hold it in front of our face, it becomes not just a lens through which we see, but a symbol of distance: this moment, this image, matters because it will matter somewhere else, somewhen else. There's nothing wrong with wanting to preserve the moment, but when the apparatus becomes the medium through which we perceive everything - when we feel we must record a photonic image of everything to make the moment real, reality itself somehow becomes less to us.

Icons As Luminous Doorways

This summer I had the privilege of visiting the Monastery of Hosios (Saint) Loukas near Delphi in Greece. I'm not Orthodox, but I have real appreciation for what I learn from the Orthodox traditions. An Orthodox priest in my town has told me that icons are not objects of worship, but means of worship, images that help us to pray, just as windows help us to see. The pray-er who regards the icon isn't supposed to see the icon, but, as with windows, to see through the icon. In some sense the artistic image is intended to vanish when it is doing what it was intended to do. This language has been a little bit mysterious to me at times, but at the monastery this summer I had an illustrative experience: I stood in a doorway with bright sunlight shining behind me. Ahead, I could see through another doorway into the narthex of a chapel, and then through another doorway, to the altar at the far end. Beside every Orthodox altar there is an icon of Christ. This one was covered with glass, as icons often are. The glass reflected back to me the image of the doorway behind me, as though in the center of the image of Christ there were a luminous doorway. I tried to take a photo of this, but the contrasts were too great. So I took out my paper and pen and sketched what I saw. It's not a superb image, but it turned out far better than my photographic attempts did. And, as in other cases, I found myself feeling considerably more present and more respectful of the place.

The View From The Pew

This was the case with several other holy sites I visited this summer as well. I had the privilege of hearing Robert Richardson lecture on Emerson in the Unitarian church in Concord, MA this summer, and then to visit the "African Meeting House" in Boston, a site of worship and of community activism for African Americans in the 19th century. It somehow didn't feel right to let the camera intrude into these places. The pen, by contrast, felt like an instrument properly reverent. Each stroke of the pen strengthening lines became like a prayer or an act of gratitude and reverence for the places I was in. In each case I sketched a "view from my pew," the view I had while sitting as worshipers have sat there in times past - and present.

No Photos!

But to return to the complaint with which I began this piece, too many places insist that no photography be allowed inside. While participating in a Summer Institute on Transcendentalism sponsored by the National Endowment for the Humanities this summer, I was able to visit some wonderful places, like the Thoreau Homestead, several of the homes of Louisa May Alcott, and Emerson's home. Visiting these places makes me a better teacher: they help me to tell a better story about the texts and ideas that emerged from them. Bronson Alcott, Louisa May's father, may have been odd, but his oddity is fascinating and delightful. He built this outbuilding to house his Concord School of Philosophy, for instance:

Architecture As The Embodiment Of Ideas

And he had some beautiful ideas about education: like the belief that children should be allowed to learn what they love to learn, that they should become bodily and sensorily engaged in their learning, that they should run and play and have recess, that art and literature should be significant in their learning, and so on. I knew these ideas before visiting his Concord home and Fruitlands, but seeing the buildings he built to house his ideas helps me to see how he envisioned those ideas at work.

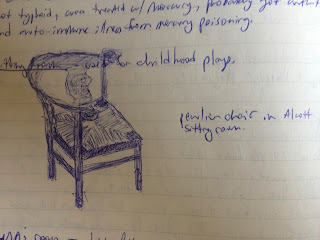

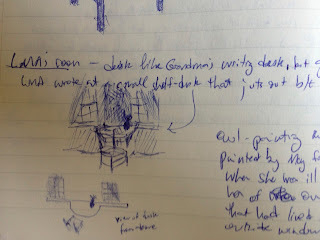

Unfortunately, I can only show you the outside of the buildings at the Alcott house, because there's no photography allowed inside, nor at the Emerson home either. So if you live far away, tant pis. I guess you'll have to just travel and visit it. Or, if you like, I can share the sketches I was able to make in our hurried tour. Yes, let's do that. I loved this chair, which is so oddly shaped. In a time when so many chairs seemed intended to make you sit ramrod straight, this one seems to invite you to slouch in different directions, to be at ease in your own body, to delight in sitting in the company of others:

The Alcotts weren't wealthy, but Bronson and his wife managed to provide each of their children with a room of their own, and each of those rooms is suited to the disposition and arts of the child. Louisa May's room has a beautiful little half-moon shelf-desk jutting out between two large windows, perfect for writing stories and books, with excellent light. When I visited, the room was full of tourists, so a photo wouldn't have captured it anyway, and my drawing is very hasty and a little cramped itself, but here's a rough idea of what it looks like while standing beside her bed, plus an attempt to give the bird's-eye view:

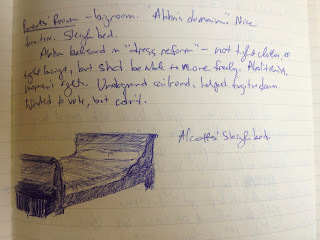

Bronson and his wife Abby had some lovely furniture, and I was especially captivated by their sleigh-bed. Its curved ends and gentle woodwork make the bed seem a place worth being, a place of rest and delight:

What I wish is that the owners and curators of these places would recognize that allowing visitors to take photos can help us to preserve the very places we are visiting, and to teach others about them. I understand the desire to make those places special, just as I understand the fear that if you allow images to be taken maybe fewer visitors will come. But for us teachers, taking pictures can be a way to allow our students to visit a place they might otherwise never go.

Thankfully, no one has yet prohibited my pen and paper. Or yours. I'm not up to Urban Sketchers quality, and may never be, but I'm not ashamed to use my pen as a visual instrument, nor to share with you what I've seen through it. And I hope you'll do the same.

Rebel Without A Camera: Museums, Images, and Memory

|

| My old Brownie. No flash! |

As a kid I found most museums boring, but now I really appreciate and enjoy them. I've spent many days of my life in the British Museum and in several museums in Athens, and each time I'm there I feel that time is rewarded with fresh discoveries and with reacquaintance with familiar objects.

Some museums have a reasonable policy of not permitting flash photography, since the bright light of camera flashes can degrade the colors of paint and dyes. Others must insist on no photography when the objects on display are on loan from owners who will not permit reproductions of their images.

But in general, I object when museums and archives prohibit photography, especially when the aim is to force more visitors to come to the physical site. Most people the world over will never be able to visit the world's great museums. And many scholars could benefit from digital images of archival materials. During a recent visit to an archive that hosts many of Henry David Thoreau's papers, I was disappointed to learn that I would not be permitted to take photos of some of the papers I wanted to read later. This forces scholars to spend more time in the archive, which means spending more money - simply prohibitive for many of us. So I type, or scribble, as quickly as I can to transcribe texts in some archives, and hope that I can somehow find what I need in the time I have.

The Ballpoint As A Tool For Seeing

But what if what you want to remember is not a text but an image? Scott Parsons, a gifted artist and a friend of mine, has taught me that one need not be very talented with a pen to begin to capture images. As Dr. Cornelius said in one of Lewis's stories, "A scholar is never without [pen and paper]," and I've tried to make that my rule, too, carrying pen and paper with me everywhere. Scott tells me that a cheap ballpoint pen is, after all, one of the best tools for seeing.

It turns out, he's right: the pen is often mightier than the camera. I think this is because the camera captures all available light, while the pen only captures what my eye and hand tell it to. The chief obstacle to overcome is the disconnect between what my eye sees and what my hand draws. Scott has pointed out to me that this is not the fault of my hand so much as a problem of mistaking what I think I see for what I actually see. In other words, it is a problem of misdirected attention, when I pay attention to what I think is there rather than to what the light is actually doing.

|

| Thoreau Farm |

|

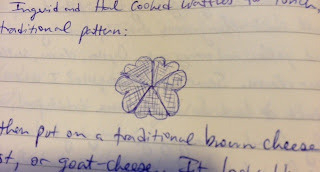

| Norwegian waffle: a bouquet of hearts |

|

| Norwegian fireplace |

I've also begun drawing inside people's homes when I'm a guest there - always with permission, of course. This summer several kind Norwegian friends took me in for a week, giving me space to write while overlooking a fjord, and cooking me delicious Norwegian food. In the evening we built fires in the hearth and talked quietly or played cards. These are fond memories with friends, but they're also memories of delight in seeing new shapes of things. Norwegians build fires and eat waffles as we Americans do, but the fireplaces and the waffle irons are different from the ones I know from my home. The waffles I saw were all shaped like heart-flowers, giving visual delight in addition to the delightful taste (though I'm not yet sold on brown cheese as a topping.) The fireplaces I saw were all open on not just one side, but two. They looked different, but it was only when I began to draw them that I noticed what I was seeing. This is a small thing, perhaps, but it is a reminder that what I take to be the natural shape of things often has as much to do with the traditions I grew up with as with nature. As an aside, when I take the time to draw pictures, it often seems to be taken as a sign of respect, which is just how I intend it: this place you live in, this object in your home, is so wonderful to me that I wish to give it my attention and make it a permanent resident in my journal, the log-book of my heart. May I? Thank you, and thank you for the hospitality that allowed me to witness this.

Pics Or It Didn't Happen

Sometimes I choose not to take photos simply because the camera is itself a sign. When we hold it in front of our face, it becomes not just a lens through which we see, but a symbol of distance: this moment, this image, matters because it will matter somewhere else, somewhen else. There's nothing wrong with wanting to preserve the moment, but when the apparatus becomes the medium through which we perceive everything - when we feel we must record a photonic image of everything to make the moment real, reality itself somehow becomes less to us.

|

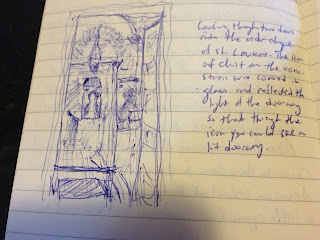

| Ecce: the heart of Christ, a luminous doorway |

This summer I had the privilege of visiting the Monastery of Hosios (Saint) Loukas near Delphi in Greece. I'm not Orthodox, but I have real appreciation for what I learn from the Orthodox traditions. An Orthodox priest in my town has told me that icons are not objects of worship, but means of worship, images that help us to pray, just as windows help us to see. The pray-er who regards the icon isn't supposed to see the icon, but, as with windows, to see through the icon. In some sense the artistic image is intended to vanish when it is doing what it was intended to do. This language has been a little bit mysterious to me at times, but at the monastery this summer I had an illustrative experience: I stood in a doorway with bright sunlight shining behind me. Ahead, I could see through another doorway into the narthex of a chapel, and then through another doorway, to the altar at the far end. Beside every Orthodox altar there is an icon of Christ. This one was covered with glass, as icons often are. The glass reflected back to me the image of the doorway behind me, as though in the center of the image of Christ there were a luminous doorway. I tried to take a photo of this, but the contrasts were too great. So I took out my paper and pen and sketched what I saw. It's not a superb image, but it turned out far better than my photographic attempts did. And, as in other cases, I found myself feeling considerably more present and more respectful of the place.

|

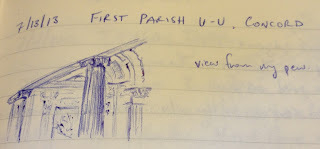

| First Parish, Concord, Mass. |

|

| African Meeting House, Boston, Mass. |

This was the case with several other holy sites I visited this summer as well. I had the privilege of hearing Robert Richardson lecture on Emerson in the Unitarian church in Concord, MA this summer, and then to visit the "African Meeting House" in Boston, a site of worship and of community activism for African Americans in the 19th century. It somehow didn't feel right to let the camera intrude into these places. The pen, by contrast, felt like an instrument properly reverent. Each stroke of the pen strengthening lines became like a prayer or an act of gratitude and reverence for the places I was in. In each case I sketched a "view from my pew," the view I had while sitting as worshipers have sat there in times past - and present.

No Photos!

But to return to the complaint with which I began this piece, too many places insist that no photography be allowed inside. While participating in a Summer Institute on Transcendentalism sponsored by the National Endowment for the Humanities this summer, I was able to visit some wonderful places, like the Thoreau Homestead, several of the homes of Louisa May Alcott, and Emerson's home. Visiting these places makes me a better teacher: they help me to tell a better story about the texts and ideas that emerged from them. Bronson Alcott, Louisa May's father, may have been odd, but his oddity is fascinating and delightful. He built this outbuilding to house his Concord School of Philosophy, for instance:

|

| Alcott's Concord School of Philosophy, Orchard House |

And he had some beautiful ideas about education: like the belief that children should be allowed to learn what they love to learn, that they should become bodily and sensorily engaged in their learning, that they should run and play and have recess, that art and literature should be significant in their learning, and so on. I knew these ideas before visiting his Concord home and Fruitlands, but seeing the buildings he built to house his ideas helps me to see how he envisioned those ideas at work.

|

| Chair in the Orchard House |

|

| Louisa May Alcott's writing desk |

|

| The Alcotts' sleigh-bed |

What I wish is that the owners and curators of these places would recognize that allowing visitors to take photos can help us to preserve the very places we are visiting, and to teach others about them. I understand the desire to make those places special, just as I understand the fear that if you allow images to be taken maybe fewer visitors will come. But for us teachers, taking pictures can be a way to allow our students to visit a place they might otherwise never go.

Thankfully, no one has yet prohibited my pen and paper. Or yours. I'm not up to Urban Sketchers quality, and may never be, but I'm not ashamed to use my pen as a visual instrument, nor to share with you what I've seen through it. And I hope you'll do the same.

∞

Hid In My Heart

Before my friend's father died, he had a stroke that left him mostly without words for a few weeks. His near-total aphasia left little intact, but there were some words that came out readily. My friend's dad had been a pastor, and when his faculty of speech left him, the words of his prayers, of the scriptures, and of the hymns and psalms were all that remained. Daily habit of repetition had ingrained them in his heart, too deep to be erased by the stroke.

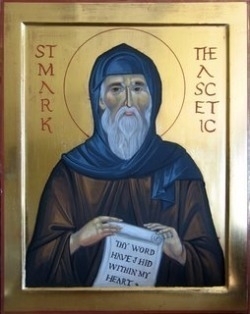

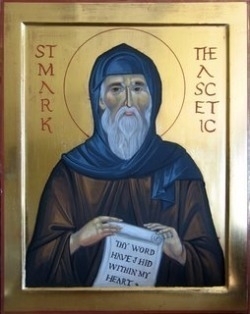

On his blog, Kelly Dean Jolley has an icon of St Mark the Ascetic, or St Mark the Wrestler, that Jolley has kindly allowed me to include here. In his hands St Mark holds a scroll that reads "Thy word have I hid within my heart." Those words are from the 119th Psalm, a long poem about scripture.

When I was in college, my French professor Charles Nunley required me to memorize a new poem every week. Every week or two I'd go to his office and he would name one of the poems I'd learned and expect me to recite it, and then to discuss it. I'm not a great memorizer, so it was painful work, but I've been grateful for the discipline every year since then. It is a gift to have verses hidden in my heart.

When I was in college, my French professor Charles Nunley required me to memorize a new poem every week. Every week or two I'd go to his office and he would name one of the poems I'd learned and expect me to recite it, and then to discuss it. I'm not a great memorizer, so it was painful work, but I've been grateful for the discipline every year since then. It is a gift to have verses hidden in my heart.

I am reminded of Mary, the mother of Jesus, when she heard what the shepherds were saying. Luke tells us that she "treasured these things in her heart," which I take to mean that she heard them, and then put them in that front room of her memory, the palm and fingertips of the mind where we touch and explore and consider ideas, turning them over and over again.

Well, this is what I do with treasured verses, anyway. Like I said, I'm a poor memorizer. But when I work at it, I hold the verses at mind's-eye level and gaze at them, running my inner eye down the length of them repeatedly, considering the way the grain moves and feeling the heft of the words until the grooves of my mind fit the notches of the words like a key. Because I hope that what I have hid in my heart will be like the Brothers Grimm's "Golden Key," which opens...well, I had better not tell you. Read it for yourself.

I wonder - when the great grinding erasure of time scrubs away at my memories, what will be left? What grooves in my grain will be too deep to scrape away? What treasures, what verses, what songs of my species will be buried too deep in my heart for the thief of time to steal?

On his blog, Kelly Dean Jolley has an icon of St Mark the Ascetic, or St Mark the Wrestler, that Jolley has kindly allowed me to include here. In his hands St Mark holds a scroll that reads "Thy word have I hid within my heart." Those words are from the 119th Psalm, a long poem about scripture.

When I was in college, my French professor Charles Nunley required me to memorize a new poem every week. Every week or two I'd go to his office and he would name one of the poems I'd learned and expect me to recite it, and then to discuss it. I'm not a great memorizer, so it was painful work, but I've been grateful for the discipline every year since then. It is a gift to have verses hidden in my heart.

When I was in college, my French professor Charles Nunley required me to memorize a new poem every week. Every week or two I'd go to his office and he would name one of the poems I'd learned and expect me to recite it, and then to discuss it. I'm not a great memorizer, so it was painful work, but I've been grateful for the discipline every year since then. It is a gift to have verses hidden in my heart.I am reminded of Mary, the mother of Jesus, when she heard what the shepherds were saying. Luke tells us that she "treasured these things in her heart," which I take to mean that she heard them, and then put them in that front room of her memory, the palm and fingertips of the mind where we touch and explore and consider ideas, turning them over and over again.

Well, this is what I do with treasured verses, anyway. Like I said, I'm a poor memorizer. But when I work at it, I hold the verses at mind's-eye level and gaze at them, running my inner eye down the length of them repeatedly, considering the way the grain moves and feeling the heft of the words until the grooves of my mind fit the notches of the words like a key. Because I hope that what I have hid in my heart will be like the Brothers Grimm's "Golden Key," which opens...well, I had better not tell you. Read it for yourself.

I wonder - when the great grinding erasure of time scrubs away at my memories, what will be left? What grooves in my grain will be too deep to scrape away? What treasures, what verses, what songs of my species will be buried too deep in my heart for the thief of time to steal?

∞

Drawing Outside The Lines: Marginalia and E-Books

I was an early adopter of the Kindle, but I stopped using it several years ago. The books I most wanted weren't (and many still aren't) available for it, and it was hard to use it as I like to use books.

You see, I am an annotator. I draw in books.

Everyone told me when I was a kid that you should NOT draw in books. But I can't help it.

Last summer my sister-in-law, seeing me read with a pencil in my hand, asked me if I always do that. I hadn't really thought about it as unusual until then, but yes, I guess I do. That way my reading becomes a kind of conversation with the book. The author writes, and I write back.

It is becoming a bit easier to annotate e-books, but we have a long way to go, perhaps because we have structured our computers to think in a linear fashion. Computers think in stoichedon, in lines and ranks, like soldiers in formation. Which is a good way to organize information, but it's not the only way, because it's not the only way lines can move. "Idea mapping" or "mind mapping" is another way. This can be expanded to three dimensions or more, as well. Think of a way a line can move and you have another way of taking notes.

Over the years I have devised my own shorthand for note-taking. For some things, I borrow old conventions of abbreviation and expand them, like this:

And so on. Some words, like selah, have entered my annotative vocabulary because they say so much so briefly. (See footnote 3 here, about "selah.")

At times, I've also found it helpful to invent new symbols, pictograms of whole ideas, sentences that can be written a single picture. I can do these with a flick of the pen, but they're much harder to incorporate into a digital text.

I draw lines from one page to the next to connect ideas. I circle names when they first appear in a text so that I can find them again. I draw vertical lines beside paragraphs to quickly highlight long sections of text. A double line emphasizes that highlighting.

I draw maps, and sketch pictures. Sometimes I write in other languages, other alphabets, when those other languages get the idea down more quickly, or more carefully. I haven't written music in books, but I don't see why you couldn't.

And all of that becomes an icon of a conversation. The annotated page is no longer text; it is an image, and a symbol of a set of relations between ideas and authors.

When I was in grad school, José Vericat (who did not know me from Adam) kindly gave me a list of books belonging to Charles Peirce and housed in one of Harvard's libraries. Peirce died in 1914, but his lines and words still illuminate his reading of those pages.

Another bit of scholarly generosity was shown to me a few years ago when I was working on my book on the environmental vision of C.S. Lewis at the Wade Center. The director, Christopher Mitchell, learned of my interest in Lewis's reading of Henri Bergson. Mitchell brought me Lewis's copy of Bergson's Évolution Créatrice to peruse. Every page is covered with marginalia written by Lewis as he recovered from his war injuries.

I think my favorite part of Thomas Cahill's book, How The Irish Saved Civilization, was seeing the facsimiles of marginal paintings - including some racy self-portraits - by monks who copied books in Ireland in the middle ages.

My point in this long blog post? Keep drawing in books. And maybe I'll get another Kindle someday if they can figure out a way to make it easy for me to draw outside the lines. And to preserve those drawings for posterity.

You see, I am an annotator. I draw in books.

Everyone told me when I was a kid that you should NOT draw in books. But I can't help it.

Last summer my sister-in-law, seeing me read with a pencil in my hand, asked me if I always do that. I hadn't really thought about it as unusual until then, but yes, I guess I do. That way my reading becomes a kind of conversation with the book. The author writes, and I write back.

It is becoming a bit easier to annotate e-books, but we have a long way to go, perhaps because we have structured our computers to think in a linear fashion. Computers think in stoichedon, in lines and ranks, like soldiers in formation. Which is a good way to organize information, but it's not the only way, because it's not the only way lines can move. "Idea mapping" or "mind mapping" is another way. This can be expanded to three dimensions or more, as well. Think of a way a line can move and you have another way of taking notes.

Over the years I have devised my own shorthand for note-taking. For some things, I borrow old conventions of abbreviation and expand them, like this:

could - cd

would - wd

should - shd

something - s/t

everything - e/t

nothing - n/t

because - b/c

nevertheless - n/t/l

And so on. Some words, like selah, have entered my annotative vocabulary because they say so much so briefly. (See footnote 3 here, about "selah.")

At times, I've also found it helpful to invent new symbols, pictograms of whole ideas, sentences that can be written a single picture. I can do these with a flick of the pen, but they're much harder to incorporate into a digital text.

I draw lines from one page to the next to connect ideas. I circle names when they first appear in a text so that I can find them again. I draw vertical lines beside paragraphs to quickly highlight long sections of text. A double line emphasizes that highlighting.

I draw maps, and sketch pictures. Sometimes I write in other languages, other alphabets, when those other languages get the idea down more quickly, or more carefully. I haven't written music in books, but I don't see why you couldn't.

And all of that becomes an icon of a conversation. The annotated page is no longer text; it is an image, and a symbol of a set of relations between ideas and authors.

When I was in grad school, José Vericat (who did not know me from Adam) kindly gave me a list of books belonging to Charles Peirce and housed in one of Harvard's libraries. Peirce died in 1914, but his lines and words still illuminate his reading of those pages.

Another bit of scholarly generosity was shown to me a few years ago when I was working on my book on the environmental vision of C.S. Lewis at the Wade Center. The director, Christopher Mitchell, learned of my interest in Lewis's reading of Henri Bergson. Mitchell brought me Lewis's copy of Bergson's Évolution Créatrice to peruse. Every page is covered with marginalia written by Lewis as he recovered from his war injuries.

I think my favorite part of Thomas Cahill's book, How The Irish Saved Civilization, was seeing the facsimiles of marginal paintings - including some racy self-portraits - by monks who copied books in Ireland in the middle ages.

My point in this long blog post? Keep drawing in books. And maybe I'll get another Kindle someday if they can figure out a way to make it easy for me to draw outside the lines. And to preserve those drawings for posterity.