journalism

- Support good schools. One of the best defenses against a nation falling apart is a well-educated populace. People who are able to think for themselves are less likely to let others do their thinking for them, which is one of the surest defenses against abdicating to a tyrant. People who know their rights and their history will be well-prepared to fight to defend them. People who only know how to fight but don't know what they're fighting for promote instability in government.

- Promote economic opportunity for everyone. We celebrate Dr. King as a promoter of equal rights, but it's worth remembering that for him those rights were closely tied to the opportunity to exercise them and to help one's family to flourish.

- Encourage bright people in your community to become teachers. Public school teachers play too important a role for us to not want our brightest minds in our classrooms. I'm not just talking about STEM fields, either. Literature, history, social sciences and arts are the disciplines that shape our imaginations. Without good art and good stories, you don't have a nation, period.

- Subscribe to your local newspaper. Here are two of the most important professions for any democracy: law and journalism. Without defense attorneys to defend rights, equal rights don't mean much. And without investigative journalism, power will corrupt governors unchecked. Your subscription is your share of the paycheck of people who will watch the custodians of the state. There's not much more important than that.

∞

On Telling Stories

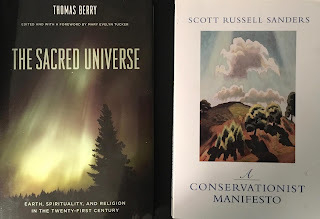

Posted for your consideration; words from two authors whose writing I find helpful, followed by a little commentary from me.

“Knowing on some intuitive level that we humans are guided by story, he ultimately called for the telling of the universe story. He felt that it was only in such a comprehensive scale that we could situate ourselves fully. His great desire was to see where we have come from and where we are going amid ecological destruction and social ferment. It was certainly an innovative idea, to announce the need for a new story that integrated the scientific understanding of evolution with its significance for humans. This is what he found so appealing in Teilhard’s seminal work."

“I’m one who dwells outside the camp of literary theory—so far outside that I can’t pretend to know much of what goes on there. I know scarcely more about deconstruction or postmodernism, say, than bumblebees and hummingbirds know about engineering. I don’t mean to brag of my ignorance nor to apologize for it, but only to explain why I’m not equipped to engage in debates about literary theory. What I can do is express my own faith in storytelling as a way of seeking the truth. And I can say why I believe we’ll continue to live by stories—grand myths about the whole of things as well as humble tales about the commonplace—as long as we have breath.”

A few years ago my wife and I, along with another family at our university, established a scholarship for Native American and First Nations students who wish to study to become storytellers. (Feel free to add to it by giving here if you are so inclined.)

Some people have since asked us why we did not invest our money in something more practical like helping individual students get into business or medical school. After all, that's where the money is, and higher income can correspond to greater independence and greater influence.

We see their point, but we both have committed ourselves to what might be considered storytelling disciplines because we think that stories shape lives and communities. A free society depends on good investigative journalists, good attorneys, and good public schools. A thriving society depends as well on good art and literature. And while religion has its downsides, it also has very strong upsides, and communities draw great benefit from healthy faith communities that remind us of our values, that give us places to congregate, to engage in commentary and contemplation, to welcome new life, to sustain commitments, to help us to mourn.

We often talk about the importance of STEM disciplines and healthcare, but I think we would do well to pay a little more attention to the way that good storytelling shapes healthcare (and the way bad storytelling makes us doubt good health practices like vaccination, for instance.)

I am persuaded that stories shape communities. They take what we have received from the past and transform and transmit it. If I am right, then I am prudent to invest in good storytelling. In the case of Native American and First Nations communities, I know just enough to know that there's a lot I don't know. And I'd like to know more.

I've been working with Bio-Itzá, a small Maya Itzá environmental group in Guatemala for the last decade, and I am constantly learning from the stories of their few surviving elders who grew up hearing the Itzá language spoken. The preservation of those words and stories means not just the preservation of a few tall tales, but the preservation of everything that is encoded and deeply rooted in those stories. The stories are cultural and ecological palimpsests, and when the Itzá elders tell them, they are passing on far more than mere words.

So my wife and I are committed to helping others to tell their stories. Because "we are guided by story," and "storytelling [is] a way of seeking the truth," and "we'll continue to live by stories."

“Knowing on some intuitive level that we humans are guided by story, he ultimately called for the telling of the universe story. He felt that it was only in such a comprehensive scale that we could situate ourselves fully. His great desire was to see where we have come from and where we are going amid ecological destruction and social ferment. It was certainly an innovative idea, to announce the need for a new story that integrated the scientific understanding of evolution with its significance for humans. This is what he found so appealing in Teilhard’s seminal work."

-- Mary Evelyn Tucker, in her preface to Thomas Berry’s The Sacred Universe. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009) (emphasis is mine)

“I’m one who dwells outside the camp of literary theory—so far outside that I can’t pretend to know much of what goes on there. I know scarcely more about deconstruction or postmodernism, say, than bumblebees and hummingbirds know about engineering. I don’t mean to brag of my ignorance nor to apologize for it, but only to explain why I’m not equipped to engage in debates about literary theory. What I can do is express my own faith in storytelling as a way of seeking the truth. And I can say why I believe we’ll continue to live by stories—grand myths about the whole of things as well as humble tales about the commonplace—as long as we have breath.”

-- Scott Russell Sanders, A Conservationist Manifesto. (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2009) (emphasis is mine)

*****

A few years ago my wife and I, along with another family at our university, established a scholarship for Native American and First Nations students who wish to study to become storytellers. (Feel free to add to it by giving here if you are so inclined.)

Some people have since asked us why we did not invest our money in something more practical like helping individual students get into business or medical school. After all, that's where the money is, and higher income can correspond to greater independence and greater influence.

We see their point, but we both have committed ourselves to what might be considered storytelling disciplines because we think that stories shape lives and communities. A free society depends on good investigative journalists, good attorneys, and good public schools. A thriving society depends as well on good art and literature. And while religion has its downsides, it also has very strong upsides, and communities draw great benefit from healthy faith communities that remind us of our values, that give us places to congregate, to engage in commentary and contemplation, to welcome new life, to sustain commitments, to help us to mourn.

We often talk about the importance of STEM disciplines and healthcare, but I think we would do well to pay a little more attention to the way that good storytelling shapes healthcare (and the way bad storytelling makes us doubt good health practices like vaccination, for instance.)

I am persuaded that stories shape communities. They take what we have received from the past and transform and transmit it. If I am right, then I am prudent to invest in good storytelling. In the case of Native American and First Nations communities, I know just enough to know that there's a lot I don't know. And I'd like to know more.

I've been working with Bio-Itzá, a small Maya Itzá environmental group in Guatemala for the last decade, and I am constantly learning from the stories of their few surviving elders who grew up hearing the Itzá language spoken. The preservation of those words and stories means not just the preservation of a few tall tales, but the preservation of everything that is encoded and deeply rooted in those stories. The stories are cultural and ecological palimpsests, and when the Itzá elders tell them, they are passing on far more than mere words.

So my wife and I are committed to helping others to tell their stories. Because "we are guided by story," and "storytelling [is] a way of seeking the truth," and "we'll continue to live by stories."

∞

Newspapers, Sports, and Healthy Societies

Everywhere I've lived I've subscribed to the local newspaper. I do so because I think it's important to be informed about what's happening in my community, and because buying the local paper is like a voluntary tax you pay when you love democracy. It funds investigative reporting about local politics, which, while imperfect, is one of the keys to fighting corruption.

I have caught some of de Tocqueville's enthusiasm for the way journalism can pump the lifeblood of a free society. Subscription to one's local paper is an act of patriotism. It is a commonplace of contemporary life in the United States to say that our freedom is won and preserved by soldiers. But this is, at best, only partly true, and history shows that armed men can both help and hinder freedom. Armies may be helpful, but there are other services that are more essential to freedom: lawyers, educators, and journalists.

But my idealism concerning journalism contends with my cynicism. Publishers of news are, after all, publishers; and publishers must pay their bills, too. They've got to sell ads, which means they can't risk offending those who buy ads. Right now we are in one of those times when there are a very few companies that own very many of the news outlets, and it's hard to imagine that doesn't affect both the slant of news stories told and the way those stories are selected and omitted in the first place. And they've got to print what we want to buy.

All this is a prelude to something else I have in mind to write over the next few days, about the relationship between sports and education, a question at least as old as Plato's Republic. I begin here by noting the role sports play in our news. How much of television news is devoted to sports? On any given day, a third of my local newspaper reports local and national and international sports stories.

This raises several questions for me. Why does this hold such fascination for us? And is our fascination with sports healthy?

Since some of what I will say about sports will seem critical, let me point out that I'm not opposed to sports. I'm a member of a society devoted to philosophy and sport, and I love outdoor recreation. I swam for the varsity team in my high school; I played club ultimate in college; I encouraged my kids to play various sports like flag football, gymnastics, little league, and soccer throughout their youth; and I am now the faculty advisor for my college's martial arts club and I am a U-19 recreational league soccer coach in my city. Sports are important; but that does not mean that all the attention we give to sports is well given.

So, once again, I begin with noticing the attention our newspapers give to sports. Plainly we need our journalists to attend to judges and legislators, to governors and police departments, because all of those are public offices endowed with public trust. Journalists are one of the main ways we prevent the violation of that trust. So what about sports? Is the presence (we could even say the domination) of sporting news merely a distraction from the real work of journalism? Is it a necessary evil to get us to buy the paper and to support the important democratic work of reporting?

One could argue that we need newspapers to watch athletes and coaches and owners of athletic teams to ensure that their influence on society is not unjust. But this cuts both ways: were it not for the attention we already give to sport, the influence of athletes, coaches, and owners would be minimal. The fact that newspapers report so much about sport is the symptom; we ourselves, and our attention to sport are the cause. It is not something called "sport" that is at issue here, nor the leaning of the journalists, but rather, the attention we ourselves pay it. If newspapers are physicians of our civic life, then we are the patient; and the doctor can only do so much to make us healthy if we will not do our part, too.

I have caught some of de Tocqueville's enthusiasm for the way journalism can pump the lifeblood of a free society. Subscription to one's local paper is an act of patriotism. It is a commonplace of contemporary life in the United States to say that our freedom is won and preserved by soldiers. But this is, at best, only partly true, and history shows that armed men can both help and hinder freedom. Armies may be helpful, but there are other services that are more essential to freedom: lawyers, educators, and journalists.

But my idealism concerning journalism contends with my cynicism. Publishers of news are, after all, publishers; and publishers must pay their bills, too. They've got to sell ads, which means they can't risk offending those who buy ads. Right now we are in one of those times when there are a very few companies that own very many of the news outlets, and it's hard to imagine that doesn't affect both the slant of news stories told and the way those stories are selected and omitted in the first place. And they've got to print what we want to buy.

All this is a prelude to something else I have in mind to write over the next few days, about the relationship between sports and education, a question at least as old as Plato's Republic. I begin here by noting the role sports play in our news. How much of television news is devoted to sports? On any given day, a third of my local newspaper reports local and national and international sports stories.

This raises several questions for me. Why does this hold such fascination for us? And is our fascination with sports healthy?

Since some of what I will say about sports will seem critical, let me point out that I'm not opposed to sports. I'm a member of a society devoted to philosophy and sport, and I love outdoor recreation. I swam for the varsity team in my high school; I played club ultimate in college; I encouraged my kids to play various sports like flag football, gymnastics, little league, and soccer throughout their youth; and I am now the faculty advisor for my college's martial arts club and I am a U-19 recreational league soccer coach in my city. Sports are important; but that does not mean that all the attention we give to sports is well given.

So, once again, I begin with noticing the attention our newspapers give to sports. Plainly we need our journalists to attend to judges and legislators, to governors and police departments, because all of those are public offices endowed with public trust. Journalists are one of the main ways we prevent the violation of that trust. So what about sports? Is the presence (we could even say the domination) of sporting news merely a distraction from the real work of journalism? Is it a necessary evil to get us to buy the paper and to support the important democratic work of reporting?

One could argue that we need newspapers to watch athletes and coaches and owners of athletic teams to ensure that their influence on society is not unjust. But this cuts both ways: were it not for the attention we already give to sport, the influence of athletes, coaches, and owners would be minimal. The fact that newspapers report so much about sport is the symptom; we ourselves, and our attention to sport are the cause. It is not something called "sport" that is at issue here, nor the leaning of the journalists, but rather, the attention we ourselves pay it. If newspapers are physicians of our civic life, then we are the patient; and the doctor can only do so much to make us healthy if we will not do our part, too.

∞

An Ounce Of Prevention

An old Chinese legend tells about a man who was searching for the world's greatest physician.* He learns of a man who can heal any illness, and he assumes that this healer must be the one he is seeking. The healer denies this, saying that another physician is even greater. The greatest physician is the one who can heal any disease before it even begins.

I've lost track of how many times I've heard someone say recently that the point of the Second Amendment is, first of all, to safeguard the other rights enumerated in the Constitution, and second, that a well-regulated militia is necessary in case we ever need to overthrow a government that has turned into a tyranny.

I have a little (though not much) sympathy with the second of those positions, but the first is, I think, simply wrong. Here's why: the First Amendment is itself an extremely powerful tool, and it is fitting that it should precede the Second, because an attempt to solve problems by reasonable words should always precede the attempt to solve our problems by force. In other words, if we exercise our First Amendment rights responsibly, we will never need to invoke the Second to overthrow our government. One of the beautiful things about our Constitution is the way it provides means for us to address unjust power grabs by our government officials without starting an insurrection.

But the bigger problem is one of what fills our hearts and minds: Focusing our attention on preparing to overthrow a future tyranny is like a physician preparing to euthanize a patient who might someday become ill. Yes, it is possible to "cure" any illness by killing the patient, but it's not good medicine. We need more than just preparedness to kill a disease; we need to promote good health as well.

If you're concerned about the nation becoming a tyranny, buying more guns is a poor response. Here are some far better responses:

* Thomas Cleary tells this story in the translator's introduction to his edition of Sun Tzu's The Art Of War (Shambhala: Boston and London, 1988) p. 1.

I've lost track of how many times I've heard someone say recently that the point of the Second Amendment is, first of all, to safeguard the other rights enumerated in the Constitution, and second, that a well-regulated militia is necessary in case we ever need to overthrow a government that has turned into a tyranny.

I have a little (though not much) sympathy with the second of those positions, but the first is, I think, simply wrong. Here's why: the First Amendment is itself an extremely powerful tool, and it is fitting that it should precede the Second, because an attempt to solve problems by reasonable words should always precede the attempt to solve our problems by force. In other words, if we exercise our First Amendment rights responsibly, we will never need to invoke the Second to overthrow our government. One of the beautiful things about our Constitution is the way it provides means for us to address unjust power grabs by our government officials without starting an insurrection.

But the bigger problem is one of what fills our hearts and minds: Focusing our attention on preparing to overthrow a future tyranny is like a physician preparing to euthanize a patient who might someday become ill. Yes, it is possible to "cure" any illness by killing the patient, but it's not good medicine. We need more than just preparedness to kill a disease; we need to promote good health as well.

If you're concerned about the nation becoming a tyranny, buying more guns is a poor response. Here are some far better responses:

*****

* Thomas Cleary tells this story in the translator's introduction to his edition of Sun Tzu's The Art Of War (Shambhala: Boston and London, 1988) p. 1.