labs

- This too is related to technology, of course. If the class is focused on video screens, then all the chairs will face the screens, and the classroom might even be structured like a theater. Etymologically, "theater" means something like "a place of gazing," and theaters tend to encourage people to gaze. Sometimes this can work against other activities, like colloquy, small-group interaction, and really anything that involves students moving from one place to another.

- If that last sentence made you ask,"But why do you want your students to move from one place to another?" then you see that we have some pretty strong presuppositions about how education should happen: students should sit and listen, teachers should stand and lecture. This communicates something about authority, and at times that's helpful. But it can also invite students to lean back into passivity, and to assume they have no role in their own education.

- The furniture in classrooms tells us how people are to behave, because it has been made and purchased by people who had in mind some idea of how students should behave. Most wrap-around desks are made for right-handed people, for instance. And most classroom desks I've seen expect students to sit upright, at attention, with a book open in front of them. I really don't like those desks, and I feel trapped when I sit in them. I wonder sometimes how they make my students feel. I wish we had fewer chairs and more sofas. Maybe a fireplace, or some tables with glasses of water, and ashtrays on them. I suppose I wish I could teach in pubs or ratskellers, which are, after all, places consciously designed for people to meet and discuss what most matters to them, informally, passionately, amicably.

- Classrooms that privilege video screens tend to undervalue natural light and windows. I am reminded of Emerson's reflection on a boring sermon he once heard. Emerson wrote, in his Divinity School Address, that while the minister droned on, Emerson looked out the window at the falling snow, which, he proclaimed, preached a better sermon than the minister. I have no doubt that nature can often give a better lecture than I can.

∞

South Fork, Eagle River

After breakfast we put sack lunches in the cooler and threw our backpacks in the fifteen-passenger van. Half an hour later we were piling out at the state park on the South Fork of the Eagle River.

The houses here are ugly. Taken on their own, any one of them is a beautiful building. Plainly this is spendy real estate in God’s country. But the houses look like they were lifted from the pages of some little-boxes-full-of-ticky-tacky architectural lust propaganda and carpet-bombed on the hillside, then allowed to remain wherever they fell. There is no order, no sense that the houses were built for the place. Every one of them is a garish, angular excrescence on the opposite hillside. No doubt their inmates would disagree with my assessment; they only see the houses up close, and from the inside. They must have no idea how out of place their unnatural rectangles look against the sweeping slope of the Chugach Range. No doubt, when you’re on the other side of those big plates of glass, gazing over here at the state park over your morning K-cup, the view is precious. But when you’re in the state park, looking back, there is nothing on the opposite hillside to love. Over here, there is only regret that these people believed that you could buy both the land and the landscape.

It’s about three miles’ hike in to first bridge in state park. A fairly easy up-and-down walk. It’s raining. Spitting, really, what they call chipichipi in Guatemala, a constant drizzle. The sky is a palette of cottony grays that have lowered themselves onto the mountaintops. There is a clear line below which the mountains are visible. Above it, clouds roll and shift.

I shiver a little in my heavy raincoat and think about putting on my rain pants, but I know I’ll be too hot if I do. Some of my students are wearing shorts.

At the footbridge we sit and eat our lunches. The university has packed us red delicious apples (a mendacious name), bags of honey Dijon potato chips, and turkey sandwiches with lettuce and onions. It’s not good turkey, but no one cares. This is a lovely place. We have other food in this place.

The river is only fifteen feet wide here, and it is the color of chalk, like diluted Milk of Magnesia. Taking off my shoes, I wade in. Immediately my feet start to ache with cold. Turning over a stone, I look at its underside. The gray water drips off and a tiny larva wriggles to get out of the light. It's too small to identify it, maybe a miniscule stonefly. A huge blue dragonfly cruises over the river, darting past me.

There are lots of wildflowers up here. One of my students is on the ground with her laminated guidebook, puzzling over one specimen. I've been carrying these guides everywhere, but they're only helpful for about seventy-five percent of the common stuff. There's just too much life here to get it all in a book.

The flowers grow in so many colors, so many strategies for getting the scarce pollinators' attention in the brief summer. Yellows, purples, and blues predominate. The guidebook warns me about several of the purples: DO NOT EAT THIS! Some of them are poisonous. So are a few of the yellows. This is a beautiful place, but it's also a harsh place, and life clings to the edge. Poison is one good way not to get eaten, I suppose. Looking up the mountain, the trees give way to shrubs a hundred yards above us. A hundred yards more and there's only grass. Above that, I can only see rock.

Some of these plants have another strategy: rather than avoiding getting eaten, they invite it. Berries are the way some plants make use of animals to carry their seeds to new places. Bear scat, full of seeds, is all along the trails here. Each mound is a nursery where some new plant may grow in the fertile dung.

There is a kind of berry like a blueberry that grows on something that looks like a mix between evergreens and moss, only a few inches high. Some people call it "mossberry," appropriately. Some locals call it a blackberry. Matt tells us they're crowberries, as he gathers a handful. He eats some and then the students tentatively pick and eat some too.

We spend three hours there at the bridge, observing. There's so much to see. Some of us write, some draw, some stare at the peaks that surround us. A few doze off. I get out my watercolors and try to paint the landscape, but I'm quickly frustrated. There are so many greens and grays and blues, and I'm no good at mixing colors. I keep painting anyway. I can at least try to get the shapes right, I think, but I'm wrong about that, too. The mountains are stacked up in layers, and the lines look clean and clear at first, but when I try to focus on them they blur into one another. The hanging glacier at the end of the valley looms over us, silent and white and yet so eloquent. The glaciers are what made all of this, and even though they have retreated, the river runs with their tillage, the plants grow in their finely ground dust, the smooth slopes were ground smooth by millennia of ice.

Upstream, Brenden hooks his first-ever dolly varden. This is his first fish in Alaska. He is positively glowing with delight. He cradles it in his hand and then quickly returns it to the water pausing only to admire this vibrant glacial relic of a char. It too depends on the glacier.

The temperature is constantly shifting as the sun comes in and out of the clouds. Each part of the valley takes its turn being illuminated: the river shines like silver; the mountainside glows bright green and the rocks and bushes above the tree line cast sharp shadows; high in the valley small glaciers are bright ribbons streaking the blue granite. The clouds push the sunlight in ribbons across the valley. When we are suddenly in the light, we are warm.

After a few hours we walk back to the car. No one wants to go. For a while we drive in luminous silence.

The houses here are ugly. Taken on their own, any one of them is a beautiful building. Plainly this is spendy real estate in God’s country. But the houses look like they were lifted from the pages of some little-boxes-full-of-ticky-tacky architectural lust propaganda and carpet-bombed on the hillside, then allowed to remain wherever they fell. There is no order, no sense that the houses were built for the place. Every one of them is a garish, angular excrescence on the opposite hillside. No doubt their inmates would disagree with my assessment; they only see the houses up close, and from the inside. They must have no idea how out of place their unnatural rectangles look against the sweeping slope of the Chugach Range. No doubt, when you’re on the other side of those big plates of glass, gazing over here at the state park over your morning K-cup, the view is precious. But when you’re in the state park, looking back, there is nothing on the opposite hillside to love. Over here, there is only regret that these people believed that you could buy both the land and the landscape.

It’s about three miles’ hike in to first bridge in state park. A fairly easy up-and-down walk. It’s raining. Spitting, really, what they call chipichipi in Guatemala, a constant drizzle. The sky is a palette of cottony grays that have lowered themselves onto the mountaintops. There is a clear line below which the mountains are visible. Above it, clouds roll and shift.

I shiver a little in my heavy raincoat and think about putting on my rain pants, but I know I’ll be too hot if I do. Some of my students are wearing shorts.

At the footbridge we sit and eat our lunches. The university has packed us red delicious apples (a mendacious name), bags of honey Dijon potato chips, and turkey sandwiches with lettuce and onions. It’s not good turkey, but no one cares. This is a lovely place. We have other food in this place.

The river is only fifteen feet wide here, and it is the color of chalk, like diluted Milk of Magnesia. Taking off my shoes, I wade in. Immediately my feet start to ache with cold. Turning over a stone, I look at its underside. The gray water drips off and a tiny larva wriggles to get out of the light. It's too small to identify it, maybe a miniscule stonefly. A huge blue dragonfly cruises over the river, darting past me.

There are lots of wildflowers up here. One of my students is on the ground with her laminated guidebook, puzzling over one specimen. I've been carrying these guides everywhere, but they're only helpful for about seventy-five percent of the common stuff. There's just too much life here to get it all in a book.

The flowers grow in so many colors, so many strategies for getting the scarce pollinators' attention in the brief summer. Yellows, purples, and blues predominate. The guidebook warns me about several of the purples: DO NOT EAT THIS! Some of them are poisonous. So are a few of the yellows. This is a beautiful place, but it's also a harsh place, and life clings to the edge. Poison is one good way not to get eaten, I suppose. Looking up the mountain, the trees give way to shrubs a hundred yards above us. A hundred yards more and there's only grass. Above that, I can only see rock.

Some of these plants have another strategy: rather than avoiding getting eaten, they invite it. Berries are the way some plants make use of animals to carry their seeds to new places. Bear scat, full of seeds, is all along the trails here. Each mound is a nursery where some new plant may grow in the fertile dung.

There is a kind of berry like a blueberry that grows on something that looks like a mix between evergreens and moss, only a few inches high. Some people call it "mossberry," appropriately. Some locals call it a blackberry. Matt tells us they're crowberries, as he gathers a handful. He eats some and then the students tentatively pick and eat some too.

We spend three hours there at the bridge, observing. There's so much to see. Some of us write, some draw, some stare at the peaks that surround us. A few doze off. I get out my watercolors and try to paint the landscape, but I'm quickly frustrated. There are so many greens and grays and blues, and I'm no good at mixing colors. I keep painting anyway. I can at least try to get the shapes right, I think, but I'm wrong about that, too. The mountains are stacked up in layers, and the lines look clean and clear at first, but when I try to focus on them they blur into one another. The hanging glacier at the end of the valley looms over us, silent and white and yet so eloquent. The glaciers are what made all of this, and even though they have retreated, the river runs with their tillage, the plants grow in their finely ground dust, the smooth slopes were ground smooth by millennia of ice.

Upstream, Brenden hooks his first-ever dolly varden. This is his first fish in Alaska. He is positively glowing with delight. He cradles it in his hand and then quickly returns it to the water pausing only to admire this vibrant glacial relic of a char. It too depends on the glacier.

The temperature is constantly shifting as the sun comes in and out of the clouds. Each part of the valley takes its turn being illuminated: the river shines like silver; the mountainside glows bright green and the rocks and bushes above the tree line cast sharp shadows; high in the valley small glaciers are bright ribbons streaking the blue granite. The clouds push the sunlight in ribbons across the valley. When we are suddenly in the light, we are warm.

After a few hours we walk back to the car. No one wants to go. For a while we drive in luminous silence.

∞

The Music of the Spheres: The Sun Is A Morning Star

Students in my Ancient and Medieval Philosophy class are required to spend at least four hours outdoors, gazing at the skies.

That may sound odd, but it arises from my conviction that philosophy needs labs. I call it my "Music of the Spheres" project, in which I invite them to consider what it would have been like to be Thales (who was one of the first to predict a solar eclipse), gazing at the night sky and thinking about the laws that seem to guide the motions of the celestial bodies.

The students are given specific instructions and they must come up with a clear research project that can be accomplished using only the tools available to ancient astronomers.

For me, the best part of the class comes at the end when I read their work, and I get to see their offhand comments, like this:

If you don't know what planets are visible right now; if you can't quickly identify a few constellations; or if you aren't sure what phase the moon is in, why not go outside and have a look? And why not share the moment with a friend?

The heavens are not yet done revealing themselves to us, and "the sun is but a morning star."

|

| The Morning Star, Good Earth State Park (SD), December 2013 |

That may sound odd, but it arises from my conviction that philosophy needs labs. I call it my "Music of the Spheres" project, in which I invite them to consider what it would have been like to be Thales (who was one of the first to predict a solar eclipse), gazing at the night sky and thinking about the laws that seem to guide the motions of the celestial bodies.

The students are given specific instructions and they must come up with a clear research project that can be accomplished using only the tools available to ancient astronomers.

For me, the best part of the class comes at the end when I read their work, and I get to see their offhand comments, like this:

"I saw the Milky Way and its Great Rift for the first time."My heart leapt when I read that one. This next one didn't make my heart leap, but it did make my heart glad, because it too is an important discovery:

"Stargazing is much more fun with a friend."We live beneath these skies but so rarely do we lie on our backs beneath them and gaze upwards. Rarely do we lift our eyes to the heavens to see what is there, and when we do, we are quick to turn away in boredom, as though it were a small thing to gaze into the greatest distances.

If you don't know what planets are visible right now; if you can't quickly identify a few constellations; or if you aren't sure what phase the moon is in, why not go outside and have a look? And why not share the moment with a friend?

The heavens are not yet done revealing themselves to us, and "the sun is but a morning star."

∞

As September approaches, people keep asking me, "Are you ready to get back in the classroom?"

As early as middle school I knew I wanted to become a college professor, and I love my job. It is a delight to spend time with young people who are curious, after all.

Years ago, my friend Matt Dickerson pointed out to me that it's also my job to help those who are not curious to see why they should be. As it turns out, that work is usually delightful, too, a rewarding challenge.

So on the whole, I love my work.

But I admit I don't love classrooms, for several reasons:

First, no matter what decade, every classroom I've been in has exhibited an unhealthy tendency towards becoming cluttered with the latest technology, and most of that tech seems to take up a lot of space and to become the center of attention. I'm not opposed to technology in the classroom, not at all. But I'm opposed to letting it get in the way, as it does when the "Smart Cart" leaves me no room for my lecture notes, or when I can't seem to turn the ceiling-mounted projector on or off. I'm a fan of chalk, because chalk allows spontaneity, and it allows for much more than alphanumeric writing in neat rows. Sadly, concerns about chalk dust getting into computers is threatening to make chalkboards disappear from my classrooms. Alas. Chalk is an excellent technology, and if it vanishes, I will mourn its loss.

Second, classroom architecture is not some value-free, neutral design. Classroom architecture makes a big difference in how people teach, and how they learn:

Which is why, as often as I can, I get my students out of the classroom. When we are reading Thoreau's Walking, we go for a walk. When I teach environmental philosophy, we often meet under the great tree in our campus quad, where I encourage students to daydream and to play with the grass, to look for worm-castings and owl pellets, feathers and seed-pods, invertebrates and fallen bits of bark. What good is it to gain the world of theoretical knowledge at the expense of knowledge gained through vital, haptic, bodily experience?

And this is why I am a preacher of the importance of study abroad. Not just travel, but serious, engaged, rigorous study in the classroom of life in another place. This is why I teach Classics in Greece every year, and why year after year I take students to Central America to study environmental philosophy and ecology.

More and more I've been trying to shift the learning focus in my classes from the classroom to the laboratory - where by "laboratory" I mean anywhere that allows students to learn with their whole person. I make my ancient philosophy students devote hours each semester to star-gazing, in part because this is what the ancients did, and in part because I don't want them to miss the stars. I want them to gaze in wonder at the firmament so that when they read Aristotle and Galileo they know that they've looked at what those great minds saw as well. We even occasionally take field trips to really dark places like the South Dakota Badlands so we can see the skies even better.

My environmental philosophy students must observe a square meter of earth for a semester, spending an hour at a time without a camera, drawing and writing about what they see, because it does not make sense to me to talk about the earth when you have not taken the time to sit upon it, to listen to it, to smell and taste it, and to see what other lives creep, and walk, and fly across it.

My friend Aage Jensen advocates the Norwegian philosophy of Friluftsliv, life and education outdoors. And when he organizes a conference on it, he eschews conference centers and holds the conference while walking through the mountains, or paddling a river. Because he believes that one should practice what one preaches, and that nature is always ready to teach.

To paraphrase the Stoic Musonius, teachers would do well to talk less and to take their students with them into the fields, because there they will learn far better and far more than in the lecture hall.

Teaching Outdoors

|

As early as middle school I knew I wanted to become a college professor, and I love my job. It is a delight to spend time with young people who are curious, after all.

Years ago, my friend Matt Dickerson pointed out to me that it's also my job to help those who are not curious to see why they should be. As it turns out, that work is usually delightful, too, a rewarding challenge.

So on the whole, I love my work.

But I admit I don't love classrooms, for several reasons:

First, no matter what decade, every classroom I've been in has exhibited an unhealthy tendency towards becoming cluttered with the latest technology, and most of that tech seems to take up a lot of space and to become the center of attention. I'm not opposed to technology in the classroom, not at all. But I'm opposed to letting it get in the way, as it does when the "Smart Cart" leaves me no room for my lecture notes, or when I can't seem to turn the ceiling-mounted projector on or off. I'm a fan of chalk, because chalk allows spontaneity, and it allows for much more than alphanumeric writing in neat rows. Sadly, concerns about chalk dust getting into computers is threatening to make chalkboards disappear from my classrooms. Alas. Chalk is an excellent technology, and if it vanishes, I will mourn its loss.

Second, classroom architecture is not some value-free, neutral design. Classroom architecture makes a big difference in how people teach, and how they learn:

|

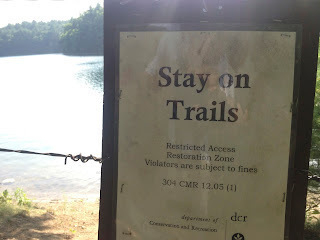

| Step off the trails! Explore! An ironic sign at Walden Pond. |

And this is why I am a preacher of the importance of study abroad. Not just travel, but serious, engaged, rigorous study in the classroom of life in another place. This is why I teach Classics in Greece every year, and why year after year I take students to Central America to study environmental philosophy and ecology.

More and more I've been trying to shift the learning focus in my classes from the classroom to the laboratory - where by "laboratory" I mean anywhere that allows students to learn with their whole person. I make my ancient philosophy students devote hours each semester to star-gazing, in part because this is what the ancients did, and in part because I don't want them to miss the stars. I want them to gaze in wonder at the firmament so that when they read Aristotle and Galileo they know that they've looked at what those great minds saw as well. We even occasionally take field trips to really dark places like the South Dakota Badlands so we can see the skies even better.

My environmental philosophy students must observe a square meter of earth for a semester, spending an hour at a time without a camera, drawing and writing about what they see, because it does not make sense to me to talk about the earth when you have not taken the time to sit upon it, to listen to it, to smell and taste it, and to see what other lives creep, and walk, and fly across it.

My friend Aage Jensen advocates the Norwegian philosophy of Friluftsliv, life and education outdoors. And when he organizes a conference on it, he eschews conference centers and holds the conference while walking through the mountains, or paddling a river. Because he believes that one should practice what one preaches, and that nature is always ready to teach.

To paraphrase the Stoic Musonius, teachers would do well to talk less and to take their students with them into the fields, because there they will learn far better and far more than in the lecture hall.

|

| Nature is full of things worth seeing. |