Law

- The economy of Nicaragua is closely tied to the economy of the United States;

- Many Nicaraguans have had to leave their family farms because cheap exports from the United States make it impossible to sell their produce and grain at competitive prices;

- Those who leave the family farm often fail to find work in the cities;

- One cause of this is that the work conditions in the cities are largely established and controlled by the international firms that can easily relocate to other poor countries if their requirements are not met. This keeps wages low, and makes it difficult for the country to receive any tax benefit from international industry;

- So capital freely flows out of the country and across borders;

- People follow the capital as it flows.

- It's more dangerous. People pulling out of driveways don't look at who is coming down the sidewalk. Try this sometime and you'll see what I mean. You probably don't look either.

- It's more dangerous. Sidewalks are for walking. I think that's why they're called sidewalks. (See that word "walk" in there?) Which means that they're not engineered for biking. Telephone poles and guy wires and signposts for motorists jut out of and across sidewalks all over town, making it easy for anyone going at a decent pace to get knocked off their bikes.

- It's much slower. Bicyclists on the sidewalk must stop at every intersection, even if there isn't a stop sign. At every intersection. Ride a bike to work tomorrow and stop completely every few hundred yards if you don't get my point. You will get it very quickly.

- In some cases it's illegal. For instance, in downtown Sioux Falls. This is because

- It's more dangerous. Small children are on the sidewalk. People walking dogs are on the sidewalk. Wheelchairs and strollers are on the sidewalk. People leave things on the sidewalks.

- Also, it's more dangerous. Many sidewalks simply aren't maintained for biking. Branches are not trimmed well, and if the concrete joints aren't level, they can ruin a wheel.

- Bicycles cause almost no road wear, so we save the city from having to pay for the damage that heavy cars quickly cause;

- Bicycles use no fossil fuels, at least not directly, so we don't increase dependence on foreign oil. We're patriots like that. If you like enriching OPEC, I guess that's your right, but I don't quite get it;

- Bicycling is better for my health, which means that I am probably decreasing everyone's health care costs and staying healthy and productive.

- Bicycling is also better for your health, because bikes don't pollute. So that clean air you;re breathing? You're welcome;

- Bicycles take up less space on the road and in parking lots, which means the road is less congested, and you get a better parking spot. Again, you're welcome.

- Support good schools. One of the best defenses against a nation falling apart is a well-educated populace. People who are able to think for themselves are less likely to let others do their thinking for them, which is one of the surest defenses against abdicating to a tyrant. People who know their rights and their history will be well-prepared to fight to defend them. People who only know how to fight but don't know what they're fighting for promote instability in government.

- Promote economic opportunity for everyone. We celebrate Dr. King as a promoter of equal rights, but it's worth remembering that for him those rights were closely tied to the opportunity to exercise them and to help one's family to flourish.

- Encourage bright people in your community to become teachers. Public school teachers play too important a role for us to not want our brightest minds in our classrooms. I'm not just talking about STEM fields, either. Literature, history, social sciences and arts are the disciplines that shape our imaginations. Without good art and good stories, you don't have a nation, period.

- Subscribe to your local newspaper. Here are two of the most important professions for any democracy: law and journalism. Without defense attorneys to defend rights, equal rights don't mean much. And without investigative journalism, power will corrupt governors unchecked. Your subscription is your share of the paycheck of people who will watch the custodians of the state. There's not much more important than that.

On Telling Stories

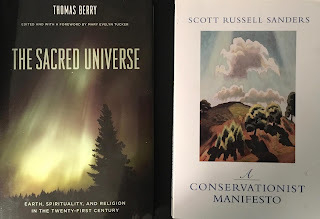

“Knowing on some intuitive level that we humans are guided by story, he ultimately called for the telling of the universe story. He felt that it was only in such a comprehensive scale that we could situate ourselves fully. His great desire was to see where we have come from and where we are going amid ecological destruction and social ferment. It was certainly an innovative idea, to announce the need for a new story that integrated the scientific understanding of evolution with its significance for humans. This is what he found so appealing in Teilhard’s seminal work."

-- Mary Evelyn Tucker, in her preface to Thomas Berry’s The Sacred Universe. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009) (emphasis is mine)

“I’m one who dwells outside the camp of literary theory—so far outside that I can’t pretend to know much of what goes on there. I know scarcely more about deconstruction or postmodernism, say, than bumblebees and hummingbirds know about engineering. I don’t mean to brag of my ignorance nor to apologize for it, but only to explain why I’m not equipped to engage in debates about literary theory. What I can do is express my own faith in storytelling as a way of seeking the truth. And I can say why I believe we’ll continue to live by stories—grand myths about the whole of things as well as humble tales about the commonplace—as long as we have breath.”

-- Scott Russell Sanders, A Conservationist Manifesto. (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2009) (emphasis is mine)

A few years ago my wife and I, along with another family at our university, established a scholarship for Native American and First Nations students who wish to study to become storytellers. (Feel free to add to it by giving here if you are so inclined.)

Some people have since asked us why we did not invest our money in something more practical like helping individual students get into business or medical school. After all, that's where the money is, and higher income can correspond to greater independence and greater influence.

We see their point, but we both have committed ourselves to what might be considered storytelling disciplines because we think that stories shape lives and communities. A free society depends on good investigative journalists, good attorneys, and good public schools. A thriving society depends as well on good art and literature. And while religion has its downsides, it also has very strong upsides, and communities draw great benefit from healthy faith communities that remind us of our values, that give us places to congregate, to engage in commentary and contemplation, to welcome new life, to sustain commitments, to help us to mourn.

We often talk about the importance of STEM disciplines and healthcare, but I think we would do well to pay a little more attention to the way that good storytelling shapes healthcare (and the way bad storytelling makes us doubt good health practices like vaccination, for instance.)

I am persuaded that stories shape communities. They take what we have received from the past and transform and transmit it. If I am right, then I am prudent to invest in good storytelling. In the case of Native American and First Nations communities, I know just enough to know that there's a lot I don't know. And I'd like to know more.

I've been working with Bio-Itzá, a small Maya Itzá environmental group in Guatemala for the last decade, and I am constantly learning from the stories of their few surviving elders who grew up hearing the Itzá language spoken. The preservation of those words and stories means not just the preservation of a few tall tales, but the preservation of everything that is encoded and deeply rooted in those stories. The stories are cultural and ecological palimpsests, and when the Itzá elders tell them, they are passing on far more than mere words.

So my wife and I are committed to helping others to tell their stories. Because "we are guided by story," and "storytelling [is] a way of seeking the truth," and "we'll continue to live by stories."

Wicked Problems in Environmental Policy

a. Do so for their perspectives, for their interests, and for their tools.

b. Ask: Who are the stakeholders?

i. Go beyond the financial stakeholders or stockholders.

ii. Include everyone who affects, or is affected by, the policy under consideration.

c. Remember Charles Peirce’s idea: science is the work of a community, not of an individual.

d. Make concept maps, and use other kinds of visualizations of the problems.

i. This is a way of utilizing a broad range of tools. Don’t just use the tools others tell you are relevant; include the arts and the sciences alike.

ii. Drawing and sketching pictures will help you to see better. As Louis Agassiz said, “the pencil is one of the best eyes.” It is often better than a camera.

iii. Music, literature, poetry, and the visual arts may be just as helpful as the tools offered by STEM fields and policy-making professions like law.

iv. If you include the arts, you wind up including the artists; similarly, if you exclude the arts, you exclude the wisdom and insight of the artists.

v. Include ordinary daily practices. Learn to fish, even if you don’t plan to fish. Hike in the woods, even if you don’t like the outdoors. These are, in a way, practices of paying attention to the world.

e. Include other voices and texts in the conversation, not just the shareholders, but all the stakeholders.

f. Define “stakeholders” as broadly as you can. Include a community across generations. Include the departed and the not-yet-born if possible.

i. Traditions might be full of wisdom, so don’t ignore them, especially if they are specific to a place. Traditions may be inarticulate wisdom that is tested by time.

ii. Plan for seven generations. I sometimes think of this as the difference between planting those crops you will harvest this year and planting hardwood trees so that they will be old-growth trees long after you are dead. Humans – and other species – need both kinds of plants.

|

| Bear scat along a salmon river, Katmai Preserve, Alaska |

2) Second, fill your toolbox—and your community’s toolbox—with bear poop. This is an inside reference my students will understand by the end of the semester, but I'll fill you in briefly: I take the time when I am in the wild to look at animal scat, because it is often a picture of what food is available to the animals, and that, in turn, is a picture of the problems the environment is facing. Paying attention to scat over time gives you a long-term picture of changes to the environment. Poop is a tool that is free, that is right in front of you, and that is easy to overlook as unimportant or distasteful. Bear poop that is full of salmon bones tells me one story; bear poop that is full of berries tells me another. I don't literally fill my toolbox with bear poop, but paying attention to negligible things like bear poop gives me new tools I wouldn't have otherwise. What does this mean for us?

3) Third, have what Peirce calls “regulative ideals”

4) Fourth, don’t expect perfection

5) Fifth, do expect growth, and strive to cultivate good things. This is the work of ethics.

6) Sixth, do expect to be part of a community that continues to work on the problems for a long time.

7) And seventh, don’t give up!

A Pretty Good Year

As my regular readers know, I'm a professor of philosophy and classics, and I teach a wide range of classes. (You can click on the "Teaching" link above to see a sampling of the courses I teach.)

Often people assume that means I wear tweed and a bowtie and that I spend my time in classrooms talking about old books. All that is true, but it's only a part of what I do.

In fact, most of my favorite classrooms are outdoors, where I'm likely to be found wearing jeans and hiking boots, a parka, or a wetsuit and snorkel.

Over the last dozen years or so my teaching and research have tended towards the environmental humanities. Think of this as the merging of the humanities side of the liberal arts with a close observation of the natural world. I consider my work to be a continuation of the work that Thales and Aristotle did when they paid close attention to animals on the ground and to the skies above, and of the work of Peirce, Thoreau, and Bugbee, all of whom let a rising trout or a solar eclipse provoke philosophical reflection.

While I don't work in an indoor laboratory, I think that education is not about the imparting of information or the filling of an empty vessel with ideas. Education is the kindling of a fire, as Plutarch wrote. And that fire is kindled by the kinds of experiences that we get in labs, art studios, shared meals, liturgies, study travel, and seminars. Lecture halls are a fine place to discuss environmental policy, to be sure. But so is a prairie, especially when you're waiting for water to boil on your camp stove, and watching the sun's beams break over the horizon and melt a light frost on your tent.

When I'm at home, I like to take my classes outside to sit under trees on campus. In the fall, I try to bring my Ancient Philosophy students camping in the Badlands of South Dakota where we can view the stars far from urban glow. Most Januaries, my students and I are in the subtropical forests of Guatemala and on a barrier island in Belize, studying ecology and culture. I rarely take a spring break, since I usually take that week to teach a course in Greece. Last summer I started teaching a class on trout and salmon in Alaska.

Those are all beautiful, memorable places, but I don't visit them as a tourist. I go to these places because I want my students to understand what is at stake when we talk about environmental regulations and practices. I want them to meet displaced people whose permafrost islands are melting or whose forests are being burned down for meager cropland. I want them to see the disappearing mangroves so that they can consider the full cost of seafood. When they stay in homes in Guatemala, my students will meet people who can never again be a mere abstraction; after we return, my students will know that the people struggling to cross borders are not nameless, faceless strangers, but people who are looking for ways to feed those they love.

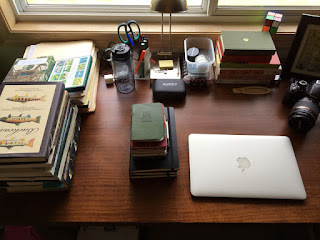

A little less than a year ago I was finishing up a year that had brought me to all these places. I taught in the South Dakota Badlands, in Central America, in Greece, and in Alaska. Along the way, I had begun studying environmental law at Vermont Law School as a way of enhancing my teaching and my research. It was a good year, and as August was winding down, my desk was covered with field notebooks full of observations from Alaska and Guatemala, ready to be written up. My field notes are usually accompanied by thousands of photographs, and hundreds of sketches. I began the fall semester last year ready to teach, and ready to write.

|

| Field notes. A picture of some of the work I do when I'm inside, and not teaching; or, if you like, a picture of my desk as I recover from my injuries. I have a lot of catching up to do. |

And then I wound up in the hospital with some serious injuries. Those injuries put a sudden stop to all my teaching last fall, and for a long time I lost most of my ability to write. (I'll try to write more about the injuries and my subsequent disabilities later; it's not an easy thing to write about yet.)

Now, as this summer hastens towards the beginning of another school year, I am able to look back on last year with a sense of good fortune - albeit mixed with one very bad day and its long-term consequences. Physically, I'm regaining my flexibility and strength, a little at a time. I'm not where I was a year ago, and I may never be there again, but I'm alive and able to walk, so I'll count that in the "win" column of my life's scorecard. Intellectually, most people seem to think I'm doing fine, so I'll also count that as a win. Although it left me exhausted each day, I was able to teach again this spring, and I plan to be back in my classrooms (Deo volente!) this fall.

But here are these field notebooks, and hundreds of unedited pages on my hard drive. It was my habit to write daily. Over the last year, recovering from a brain injury has made it hard to write more than a few sentences at a time.

This morning I was looking at some of my pictures from my research in the Arctic last summer, and I was hit with a feeling of loss. Those photos and those notes should be a book by now, and perhaps several articles and book chapters, too. Instead, over the last year, as I have waited for my body and brain to heal, and as I struggled to do my teaching, I had no strength to write.

It feels funny to say that, but perhaps I am not alone in finding that a brain injury can be slow to heal and extremely tiring. I don't say that to get your sympathy. I am blessed with a very supportive community and an amazing wife who somehow has kept our life together and nursed me through my healing process. I'm fortunate. But if you've read this far, you might consider whether there are others around you who look like they're doing well physically but who might be nursing invisible wounds or who might be struggling to cope with invisible disabilities. This past year has given me a new perspective on that by making me aware of my own disabilities, most of which you won't notice if you see me at the gym or in one of my classrooms.

I might not be able to write another book yet, so for now, here's my plan: I'll write a little at a time. Thankfully, I've got my notes, sketches, and photos. I'll start with them.

If you're curious about how a professor of philosophy and classics does research and writing about nature - and how he works to recover from a serious brain injury - you might check out some of my recent publications. My book Downstream is the result of eight years of field research on the ecology of the Appalachians, with a focus on brook trout. On this blog you'll also find my recently published poem, "Sage Creek," which might give you a glimpse of my ancient philosophy class camping and stargazing in the Badlands. Or feel free to look at my photos on Instagram. Even when I can't teach in the field, I can still wander my garden with a hand lens and camera.

National Park Law - Knopf and Stegner

“The people, to whom the Parks belong, should be given the full facts on which to base a judgment, whenever the question of intrusion on Park lands arises. The people, as taxpayers who foot the bill, should also know, with fair exactness, and from a responsible reviewing body, how much a reclamation project is going to cost them, whether in a Park or not. [....]

“The attitude of Americans toward nature has been changing—slowly, perhaps, but inexorably. Fifty thousand persons camped out in one Park, the Great Smokies, in a single summer month of 1954. That same summer I spent a night at Manitou Experimental Forest, in which a near-by campground, run by the Forest Service and at that moment without a water supply, was expected to be used by fifty thousand people before winter. In 1951 Glacier National Park had a half-million visitors; in 1953 it had more than 630,000. In that same year, the last for which total figures are available, Grand Canyon had 830,000 odd, Yellowstone 1,300,000, and Yosemite just short of a million. Those figures are impressive no matter how you take them. They mean that what the Parks and Monuments provide and preserve without impairment is increasingly appreciated and increasingly needed by more and more millions of American families.”

Alfred A. Knopf, “The National Park Idea,” in This is Dinosaur: Echo Park Country and Its Magic Rivers, Wallace Stegner, ed. 91-91. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1955) (Emphasis in boldface mine)

Steinbeck on Overfishing

John Steinbeck, The Log From The Sea Of Cortez. (Penguin, 1995, p. 205) Emphasis added. Feel free to substitute the name of any other coastal government for the word "Mexican."

When The Court Will Not Give Justice

-- The Book of Susanna, v. 9. (New Revised Standard Version)

“Just as she was being led off to execution, God stirred up the holy spirit of a young lad named Daniel, and he shouted with a loud voice, ‘I want no part in shedding this woman’s blood!’ All the people turned to him and asked, ‘What is this you are saying?’ Taking his stand among hem he said, ‘Are you such fools, O Israelites, as to condemn a daughter of Israel without examination and without learning the facts? Return to court, for these men have given false evidence against her.’”

-- The Book of Susanna, vv. 45-49. (New Revised Standard Version)

Protecting Borders, Loving Neighbors, And The Economics Of Child Migration

Too often our approach to this problem is, like many U.S. political questions, polarized into mutually repellent views about how we should view our laws. Should we reform them or enforce them? Let me suggest another angle from which to consider the problem.

Eight years ago, Reynold Nesiba (an economist who is my friend and colleague) and I co-taught a course for American students in Nicaragua. The purpose of the course was to spend time thinking and talking about the effects of globalization on a small developing nation.

We both prefer to teach contextually, so that the assertions of our readings and lectures can be supported and challenged by what the students see and experience in the places we visit.

|

| Coffee beans grown in Nicaragua. |

We spent time with collective coffee growers, and with big coffee processors; with small, independent textile workers and in an international textile plant built in a tax-free zone in Managua. We did homestays and met with development workers, a health clinic and a local church. We met with and listened to as many people, from as many points of view, as we could.

|

| Workers sort coffee beans. |

Although the course made many things unclear, it made a few things clearer. Among them are these:

If I'm right, though, then it gives some context to the persistent problem of illegal migration across our southern border, and it suggests a remedy.

The problem is plain: poor people are following the money trail, and fleeing the harsh economic conditions that prevail in poor countries.

The remedy is also plain, even if it is not easy: we need to figure out a way to increase the flow of capital into places like Nicaragua, and to do it in such a way that it increases jobs (not merely increasing the income of the top earners) and increases the tax base. One such possibility - especially if my second bullet point, above, is correct - would be to examine the way farm subsidies might actually be decreasing our ability to secure our borders. Our nation reaps profit from Nicaragua. Is it possible to do so in a way that also benefits Nicaragua?

I don't mean to pretend to be an expert here. I do have some relevant experience in Central America (from teaching regularly in Nicaragua, Guatemala, and Belize) but it's far from being hard data. But surely what we need is not fewer anecdotes but more stories from and about people who are most affected by the economies of our several American nations. If we are to love our neighbors, we need to learn who they are and what drives them. A mother who would send her young child, alone, across Mexico in search of a new life is either wicked or desperate, and the latter seems the likelier story. the roots of the word "desperate" mean "without hope." Loving our neighbors surely must include trying to give hope to the hopeless, and not merely building a wall across the only path towards hope that they can imagine.

| |

| The old cathedral of Managua. Unused since it was damaged by an earthquake 40 years ago. |

|

| A coffee cooperative in the mountains of Nicaragua. |

|

|||

| A sewing cooperative. |

Demosthenes' "Against Meidias"

The text is full of citations of Athenian law, and both its structure and content tell us a great deal about ancient jurisprudence.

Demosthenes also gives us some gems of ancient legal reasoning, reminding us that there is very little new under the sun. For instance: Meidias, a wealthy and brutish man, assaulted Demosthenes while Demosthenes was performing a sacred state function. Meidias then claimed that such assaults happen all the time, and therefore his was unimportant. Demosthenes replied that the decision of the court will affect not only this single case but that it will have the effect of deterring future assaults as well.

But on this reading I am especially enjoying Demosthenes as a handbook of erudite Attic insults. His repeated epithet against Euctemon, Ευκτημων ο κονιορτος, "dust-raising Euctemon" or "Dirty old Euctemon" is a minor example.

A far better one is this one, aimed at Meidias:

“If, men of Athens, public service consists in saying to you at all the meetings of the Assembly and on every possible occasion, ‘We are the men who perform the public services; we are those who advance your tax-money; we are the capitalists” – if that is all it means, then I confess that Meidias has shown himself the most distinguished citizen of Athens.” (Section 153; Taken from the Loeb edition. J.H. Vince, Trans. (Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1956) p.107)He hardly needs to say what follows: of course, public service consists in much more than that, and by offering these public rebukes against a man like this I am fulfilling one of my highest duties. Powerful people who use their power to abuse their fellow citizens deserve no less.

Bicycles Belong On The Road

As I've shared yesterday's story about the Sioux Falls driver who assaulted a bicyclist, other bicyclists I know have shared similar stories. It seems all the serious riders I know have had run-ins with motorists who refuse to acknowledge their right to the road.

Many of us are fast enough that we come pretty close to riding at the speed limit, so we're not really slowing things down. Most of our major streets in Sioux Falls are wide enough to permit sharing the lane - giving motorists enough room to obey the three-foot buffer mandated by city law.

Should we bike on the sidewalk? No!

But even slow cyclists have a right to the roads. Drivers sometimes tell me to bike on the sidewalk. If they weren't driving away so fast, I'd take the time to let them know what a stupid idea that is.

If you're one of those drivers who wonders why I'm not on the sidewalk, here's why:

So not only do we have the legal right to be on the road and to occupy the lane, as you can see, biking is our best option.

And no, driving is not our best option. I will admit that if you're driving a car that weighs several tons, you're safer than I am when I'm straddling a twenty-pound aluminum frame. But what I'm doing is better for all of us, even for you. Think about it:

You and I have the right to drive on public roads maintained at public expense because we all agree it is worth paying for, and the laws make it possible and safe. Those same laws, and that same public opinion, supports the right of bicyclists to use those same roads.

Surveillance and Virtue

These are signs that our technology is racing ahead of us. It is easier to create new machines for surveillance than it is to devise a set of rules for ethical use of those machines. The problem of Google Glass is not something altogether new; but the technology sharpens the ethical issues: can I wear it in the locker room at the gym? Can I wear it while talking with the police, or border guards? Can I wear it at a party where co-workers are drinking?

The problem of drones is similar: we have increased our ability to watch others without being watched. As Foucault observed, this is one of the main functions of the prison, a relatively modern invention. The prison is an architectural technology that allows us to watch over our fellow citizens without having them watch us.

|

| Be kind; love one another. |

We are unlikely to slow our own technological progress, so we must devote equal energy and resources to ethical reasoning and to ethical living. Here is where I suggest we start:

First, if you're ashamed of someone seeing what your community is doing, don't do it. It is one thing to protect trademarked secrets and patented methods of production, to enjoy the economic benefits of one's creativity. But if your reason for concealing your business process is that you know I won't buy your product if I know how it's made, you deserve to be exposed because you are manipulating me by concealing information that would affect my decisions.

Second, devote yourself to respecting the privacy and dignity of others. Do this not just for others, but for yourself. We know ourselves to be less than we wish we were; and we know that the social impulse is balanced in our species by a desire to do some things alone, unobserved, or only in intimate company. To expose those things unbidden is to dominate. It is crass, and unkind. If you do not respect others, the technologies of surveillance will become your Ring, and you will destroy your own soul.

At times these two principles will be in conflict with one another - underscoring the importance of continued ethical reasoning. We can't simply fall back on facile rules. We have got to keep thinking, and thinking hard, together. The simple principles, however, can provide a good place to start: do not attempt to dominate or destroy others. Put positively: love one another.

An Ounce Of Prevention

I've lost track of how many times I've heard someone say recently that the point of the Second Amendment is, first of all, to safeguard the other rights enumerated in the Constitution, and second, that a well-regulated militia is necessary in case we ever need to overthrow a government that has turned into a tyranny.

I have a little (though not much) sympathy with the second of those positions, but the first is, I think, simply wrong. Here's why: the First Amendment is itself an extremely powerful tool, and it is fitting that it should precede the Second, because an attempt to solve problems by reasonable words should always precede the attempt to solve our problems by force. In other words, if we exercise our First Amendment rights responsibly, we will never need to invoke the Second to overthrow our government. One of the beautiful things about our Constitution is the way it provides means for us to address unjust power grabs by our government officials without starting an insurrection.

But the bigger problem is one of what fills our hearts and minds: Focusing our attention on preparing to overthrow a future tyranny is like a physician preparing to euthanize a patient who might someday become ill. Yes, it is possible to "cure" any illness by killing the patient, but it's not good medicine. We need more than just preparedness to kill a disease; we need to promote good health as well.

If you're concerned about the nation becoming a tyranny, buying more guns is a poor response. Here are some far better responses:

* Thomas Cleary tells this story in the translator's introduction to his edition of Sun Tzu's The Art Of War (Shambhala: Boston and London, 1988) p. 1.

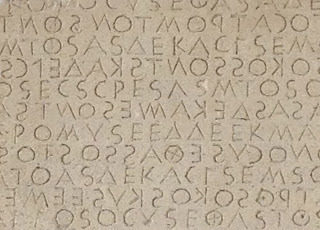

Writing, Law, and Memory in Ancient Gortyn

|

| Gortyn, Crete |

Even though I'm not an expert in the Doric dialect, I love to read this inscription, for several reasons that might interest even those who don't know Greek.

First of all, it has an unusual alphabet, containing fewer letters than modern or classical Attic Greek. It lacks the vowels eta and omega (for which it uses epsilon and omicron), and the consonants zeta, xi, phi, chi, and psi (for which it substitutes other letters or combinations of other letters: two deltas for zeta, kappa+sigma for xi; pi for phi; kappa for chi; pi+sigma for psi.)

It also uses a letter that has since fallen out of use, the digamma. The digamma (or wau) is probably related to the Hebrew letter waw (or vav) and to the Roman letter F, which it closely resembles. By the classical age it had dropped out of use in Greek, and is fairly rare, like the letters sampi and qoppa.

(There is also a digamma in Delphi, not far from the Athena Pronaia sanctuary, on an upright stone dedicated to Athenai Warganai. That second word is related to the Greek word for "work" or "deed," ergon, and also to our word "work." This stone, pictured below, evinces several peculiarities of archaic Greek script. Look at the second word, which looks like it says FARCANAI. The first letter is digamma; the third letter, rho, very much resembles the Latin "R"; the letter immediately after it, gamma, looks like a flattened upper-case "C.")

|

|

"Athenai Warganai" inscription at Delphi

|

Second, the writing is in boustrophedon style. Boustrophedon means something like "as the ox turns." Today we write in stoichedon style, in which all the letters face the same direction, like soldiers standing in formation. Boustrophedon is based on an agricultural, not a military ideal: the writer writes as a farmer plows. Write to the end of the line, and then, rather than returning to the left side of the page, turn the letters to face the opposite direction and write from right to left. When you read boustrophedon, your eye follows a zig-zag across the page -- or the stone.

Have a look at this close-up of the engraving at Gortys and look at the way letters like "E," "K," and "S" face in adjacent lines:

|

| Close-up of the Gortyn Code |

There are a lot of other reasons to like this place, and this inscription, but I'll limit myself to just one more thing for now: memory.

This inscription is one way that an ancient community deliberately remembered their laws. They wrote down what they decided, and that has affected our lives. Writing the law down makes it accessible to everyone, and makes judicial decisions transparent. It establishes a set of expectations for conduct in the community, and makes those expectations known even to aliens.

The code at Gortyn records (in Column IX, around the middle, if you're curious) the presence at court of someone in addition to the judge: the mnemon. You can see by the word's resemblance to our word "mnemonic" that it has to do with memory. The mnemon's job was to act as a witness to previous judicial decisions, and to remember them and remind the judge of those decisions. The mnemon's job was not to decide cases but to be a kind of embodiment of the law and therefore an embodiment of fairness.

Unfortunately, no mnemon lives forever. Presumably, the writing on the wall at Gortyn was a way of preserving what mattered most in the court, so that when they passed away, their memories would live on through the ages.

|

| National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Possibly a child's dish? The sixth letter is digamma. |

*****

Harold Fowler writes in a footnote to his 1921 translation of the Cratylus that under Eucleides the Athenians officially changed their alphabet from the archaic one to the Ionian alphabet in 404/403 BCE. This expanded their system of vowels, adding the long vowels eta and omega. It became known as the Euclidean Alphabet.

*****

If you can find it, Adonis Vasilakis' The Great Inscription of the Law Code of Gortyn (Heraklion/Iraklio: Mystis O.E.) is a great resource. It has a facsimile of the whole wall, a complete translation, and some helpful historical observations. ISBN 9608853400

The Course Of Nature and Laws of Nature

Today I was reading this text from Book I of Manilius' Astronomica. I'll translate the relevant part below.

The boldface text could be (loosely) translated like this: "Nature follows paths that she herself has made, and she does not stray as the inexperienced do."Nam neque fortuitos ortus surgentibus astrisnec totiens possum nascentem credere mundumsolisve assiduous partus et fata diurna,cum facies eadem signis per saecula constet,idem Phoebus eat caeli de partibus isdemlunaque per totidem luces mutetur et orbeset natura vias servet, quas fecerat ipsa,nec tirocinio peccet, circumque feraturaeterna cum luce dies, qui tempora monstratnunc his nunc illis eadem regionibus orbis,semper et ulterior vadentibus ortus ad ortumoccasumve obitus, caelum et cum sole perennet.

On the one hand, this sounds like an early articulation of the idea of laws of nature. If nature follows paths laid down by nature itself and from which it does not deviate, that would be compatible with our idea of a natural law.

Yet there's an important difference between law and path. As you walk along a path, your feet may fall more to one side of the path or the other; and over time, paths may shift, broadening with use or narrowing with desuetude. Charles Peirce, responding to advocates of Hume's argument against miracles, argues that nature is like this as well, and that what we now call laws were once called the course of nature, and Peirce thinks of them as habits that nature has taken on.

The name makes a difference, if only a slight one. Peirce was not trying to argue for particular miracles, but he was urging students of science not to insist that nature behave according to their preconceptions of law. Manilius' idea is not so far-fetched: the laws might not have been there at all, but nature took them on and then, once they became habits, nature has stuck to them. Thinking about science this way alerts us to two possibilities: first, that things might not always have been as they are, and second, that nature might still be taking on new habits. We shouldn't expect nature to stray far from its habitual paths, but on the other hand, what would prevent it from doing so?

Respect for laws and Respect for the Law

I don’t tend to talk about politics - at least not about specific candidates - on my blog or in my classroom. One of my main reasons for this (I have several) is that as a teacher of philosophy, I am more interested in the ideas than in the people running for office.

The case of Kristi Noem - a Republican running for Congress in South Dakota - is one of those cases where it’s difficult to separate the person from the ideas. I don’t mean that she is inseparable from her politics. I am instead referring to her driving record.

Many people in my state feel that Noem’s record has been subjected to enough scrutiny, and that it is just an example of her opponent, Stephanie Herseth-Sandlin, playing dirty politics. The latter may be true (I don’t pretend to know), but I don’t think the former is true. I don’t mean that we need to have a longer investigation of Noem’s driving record. But I do wonder whether Republicans should be endorsing Noem at all.

It’s not that Noem got caught speeding once. It’s not even that she has been caught speeding 20 times. It’s that her record of breaking the law is so long that it speaks of a strong disrespect for Law in general. None of us is perfect, but this record suggests that she’s a habitual speeder. One recent ticket had her clocked at 96 mph (the state speed limit is 75 on highways.) Her actions say pretty loudly that she doesn’t much care for the law. Not a good attribute for someone whose job it would be, if elected, to write the law.

Do we really want to endorse candidates who view the law as something to be obeyed by others but not by themselves? Isn’t that precisely the opposite of the character we want in our legislators? (Or have I just been reading too much Plato?)

Addendum: A friend of mine points out that while the link above states it, I do not mention that Noem also has six times failed to appear in court; and she has twice had arrest warrants issued against her. I’m not just asking Republicans if they want this to be their public face; I’m asking all of us if we want this to be the profile our legislators. A state in which the legislators do not honor the law is a state in serious trouble.