Liberal Arts

- They want to know why I continue to be a member of a church in an age when fewer and fewer people find themselves connected to traditional houses of worship or faith communities. (I have written about this in a few places, but you might like what I have written about prayer.)

- They wonder why I am still a professor in a small liberal arts college at a time when students seem disengaged, and when colleges are threatened by political headwinds, rising costs, apparent diminishing returns, and by our own decisions that weaken public opinion against us. (You can see a bit more of what I’ve written about the liberal arts here and here.

- And they wonder why I continue to work towards environmental sustainability in a place that doesn’t seem to value the environment, and where sustainability is viewed as a harmless hobby at best and a threat to business and freedom at worst. (My work focuses on the environmental humanities, and I’ve done a good deal of work in sustainability with my university, with my city, with our local zoo and aquarium, and internationally with organizations like IBM. You might also like this article I wrote about insects on Medium, but be forewarned that it is paywalled.)

- When it comes to faith, I often find others' stories more interesting than my own, and I’m glad to meet others who are seeking the way ahead with humble curiosity even if we use different words to talk about what we’re seeking and what we’re finding. So my calling is not to a building, or to a religion; rather, it feels like a consistent calling to love God and to love my neighbor as myself.

- When it comes to teaching, I have taught every age from pre-schoolers to older graduate students. I love it all. For now, I’m a tenured professor at the highest rank available to me. It took a lot of work to get here, and positions like mine are the envy of graduate students everywhere. I wouldn’t be surprised to see more and more schools eliminate tenure and reduce jobs like mine to some version of the gig economy (these things are already happening steadily around the world.) So if I were to leave this job, I’d be leaving something I probably would never find again. But I don’t feel the calling to comfortable tenure so strongly as I do feel the calling to meaningful teaching that helps others to flourish. So my calling seems always to tug me beyond my faculty office and my assigned classrooms.

- And when it comes to environmental sustainability, I often find myself scratching my head. Why wouldn’t we want to be not just good neighbors but also good ancestors? Why wouldn’t we want to pursue solutions that help people and the planet to thrive while also making sure we all flourish economically? I get it: so many of the solutions offered by environmentally-minded people threaten to cost us more in taxes, or they threaten particular practices or certain sectors of the economy. If someone came for my job or my hard-earned savings, I’d bristle as well. But it doesn’t have to be that way. We can make good use of the water we have AND we can make sure those who live downstream have clean water too. We can make good use of our soil without depleting it, and we can do it in a way that boosts profits. Etc. Here my callings all seem to come together: I feel called to help my neighbors — all of my neighbors — flourish, and to love them as myself. And to include as neighbors everything that lives, and everyone who might inherit this earth from me. I’d like my great-great-grandchildren whom I will likely never meet to look back on my life with gratitude.

- Support good schools. One of the best defenses against a nation falling apart is a well-educated populace. People who are able to think for themselves are less likely to let others do their thinking for them, which is one of the surest defenses against abdicating to a tyrant. People who know their rights and their history will be well-prepared to fight to defend them. People who only know how to fight but don't know what they're fighting for promote instability in government.

- Promote economic opportunity for everyone. We celebrate Dr. King as a promoter of equal rights, but it's worth remembering that for him those rights were closely tied to the opportunity to exercise them and to help one's family to flourish.

- Encourage bright people in your community to become teachers. Public school teachers play too important a role for us to not want our brightest minds in our classrooms. I'm not just talking about STEM fields, either. Literature, history, social sciences and arts are the disciplines that shape our imaginations. Without good art and good stories, you don't have a nation, period.

- Subscribe to your local newspaper. Here are two of the most important professions for any democracy: law and journalism. Without defense attorneys to defend rights, equal rights don't mean much. And without investigative journalism, power will corrupt governors unchecked. Your subscription is your share of the paycheck of people who will watch the custodians of the state. There's not much more important than that.

- Virginia Woolf, Mrs. Dalloway. (Mixed feelings about this one. My mind enjoyed it more than my aesthetic sense did, if that makes sense.)

- John Steinbeck, Cannery Row and Of Mice and Men. (I discovered Steinbeck late in life, thanks to a friend's recommendation. I've also recently read his Log From The Sea of Cortez and Travels With Charley In Search Of America. I think these two will forever shape me as a writer.)

- Graham Greene, Our Man In Havana, The Quiet American, The Honorary Consul, Travels With My Aunt, The Power And The Glory. (I will let the number of titles speak for itself.)

- Alan Paton, Cry, The Beloved Country. (I was surprised by how contemporary this old book felt, and by how relevant to America an African book could feel.)

- The Táin. Because I have a thing for reading really old books, and this is one of the oldest from Europe.

- China Miéville, Kraken. (London. Magical realism. Bizarre and witty.)

- J. Mark Bertrand, Back On Murder (I don't read many detective novels, but I really enjoy Bertrand's prose.)

- Cormac McCarthy, The Road. (The final lines spoke to my salvelinus fontinalis -loving heart.)

- David James Duncan, The River Why (I've re-read this one a few times. If you like trout and philosophy, you might like this book.)

- Mary Karr, Lit. (Third in a series of memoirs. Some of the best storytelling I've read in a long time. Brilliant insights into addiction, love, and prayer.)

Why Are You Still Here?

Should you be here? (I like roads like this one.)

Like my previous post, this one begins with a question others ask me fairly often:

“Why are you still here?”

Thankfully, when I hear this question people generally aren’t asking me to leave. Rather, they’re asking why I stay. And they’re usually asking about one of three things:

I have answers for each of these, and they’re all important. My faith matters to me. So does my community, and so does the environment my community inhabits. I want my neighbors to thrive, and that means I want them to live in a place that fosters health for the whole person: physical, emotional, mental, spiritual, and economic. And my idea of “neighbor” is fairly expansive, and it includes all those whose lives are connected to my own, including the lives of other species. Jesus once pointed out that not even a sparrow can fall to the ground without God noticing it. If the sparrows matter to God, then I’d like them to matter to me.

In other words, for me, these three questions people ask me are all related to one another.

I think they’re all also related to my vocation, and to my sense of calling. In some way I feel called to and by God; I feel like teaching is my vocation; and I feel called to be a good steward of all Creation.

Those “callings” are different, but they all also feel like “deep calling unto deep.” I can’t explain them, and I don’t mean to say they’re others' callings as well. But they’re part of who I am, as far as I can tell.

One thing all those callings have in common is that they all seem to be growing:

So my best answer to this question “Why are you still here?” is this: for now, I feel called to be here.

Of course, like I said, my callings all seem to grow.

It may be that soon I’ll find a better way to answer this triple calling I feel, and if so, I hope I won’t hesitate to leave tenure and comfort and my favorite ideas when I find better ones.

Because I believe we are all in this life together, and, as some of my favorite authors have said, “all flourishing is mutual.”

Of Fish and Forests

When people ask me what I do I sometimes reply “I study the relationships between fish and forests.”

A more precise way to describe my job might be to say I’m a teacher, a scholar, and a department chair and program director at my university. But that answer is pretty dry and uninteresting.

Adding detail doesn’t always help, though I could say that I teach philosophy, classics, religious studies, theology, field ecology, study abroad, environmental studies, and sustainability; and that I take my students to the places I study: rainforests in the tropics and in Alaska, deserts, and the Mediterranean.

So instead I say “fish and forests.” The words are simple and easy to understand. I hope they invite more questions, and often they do.

|

| Salmon bones on woody plants beside a river near Lake Clark, Alaska. A bear left these bones after a meal. |

The question I hope for is some version of “what do fish have to do with forests?” The short version is: nearly everything.

Nearly as good as that question is when someone points out that fish don’t live in trees. Short version of my reply: that’s not exactly true, and many of my students can tell you the various ways fish do live in trees. Here are a few:

Around the world, the edges between land and water are held together by roots, and in those places, fish find food, shelter, and places to spawn.

A great example of this is mangroves, which are some of the most important ocean nurseries. Thousands of species bear their young and lay their eggs in mangroves. The mangroves provide shelter from predators; they stabilize the soil, protecting land from hurricanes and strong waves, and protecting the sea from too much runoff. Birds, mammals, insects, and reptiles live in the branches. Fish and myriad aquatic invertebrates live among the roots.

|

| A mangrove on an island off the coast of Belize. |

We could add that there are “forests” of kelp and coral underwater, too.

Wherever birds eat fish, those birds also build the soil when they return to the land. Their waste becomes fertilizer for all manner of grasses, forbs, and trees. Visit the rivers of Alaska and you will find shrubs and trees growing on the banks, where seeds found fertile gardens in mounds of bear poop.

When a bear eats salmon and berries, the berry seeds pass through the bear undigested. The bear deposits the seeds in a steaming pile of fecundity. Bears are forest gardeners.

Here in the middle, between the tropics and the Arctic, the

Big Sioux River is entering its quiet winter’s rest. We haven’t had much rain,

and the river is ankle-deep in many places. The fish gather in deep holes that were

sculpted out by fallen trees. When the river claims a tree, that tree doesn’t

simply float away. It becomes food for beavers and decomposing insects. It

creates eddies that dig deep holes on one side and deposit sediment on the

other. Sometimes the tree becomes a new island, and new trees grow up on its

rotting wood and on the debris it collects. Raccoons grab mussels and crayfish,

and eat them in the branches. Mink and otters dine from a similar menu further

down on the bank.

|

| Tree growing on an island in the Big Sioux River. The tree makes habitat for both terrestrial and aquatic life. |

|

| Near the roots, a deep hole has been carved out. Habitat for fish, hunting grounds for raccoons and other mammals. |

|

| A fallen tree has created an island in the Big Sioux River |

Everywhere I go with my students I ask them to pay attention to the water. The fish and the forests alike need it. The forests keep the water cool and clean, and the fish fertilize the trees. Often, when I am teaching in Morocco or Spain or Greece, I ask them to notice the architecture of water, and the way it relates to our values. Religions have rituals of ablution, and ancient temples collect water from their rooftops, letting it flow down ancient marble columns that imitate the tree trunks that once made porticoes, to flow into cisterns. The narrative of the Christian scriptures begins in a forested garden, and ends in a city with a river flowing through it.

My students smile and roll their eyes at hearing me repeat the same question yet again. What do fish have to do with forests? What does water have to do with dry ground?

|

| Traditional Itzá canoes on the shore of Lake Petén Itzá. |

And then one will point out a young mangrove shoot, a migrating salmon, a traditional Itzá canoe on a lakeshore, a baptismal font, a hammam, a public fountain, a Roman aqueduct.

And we will all stop for a moment and consider the way that this water, right here, flows through every part of our lives.

Martin Luther on Liberal Education

-- Martin Luther, “To the Councilmen of All Cities in Germany that They Establish and Maintain Christian Schools,” in AE 45:357 (1524) (emphasis added) A full translation of the letter is available here.

Thoreau on Liberal Education, Wealth, and Freedom

-- Henry David Thoreau, "The Last Days of John Brown"

My Backyard Ark

Augustine once said that a key to his conversion was when he met St Ambrose. Augustine had regarded the Bible as full of flawed and problematic texts. As Augustine put it, "by taking them literally, I had found them to kill."(1) Ambrose taught Augustine that the texts of the Bible may have more than one sense. The scriptures might speak to him in more than one way. When he heard this, and heard it from a man who thought it important to study science and the liberal arts, Augustine found his spiritual home in Christianity.

Augustine once said that a key to his conversion was when he met St Ambrose. Augustine had regarded the Bible as full of flawed and problematic texts. As Augustine put it, "by taking them literally, I had found them to kill."(1) Ambrose taught Augustine that the texts of the Bible may have more than one sense. The scriptures might speak to him in more than one way. When he heard this, and heard it from a man who thought it important to study science and the liberal arts, Augustine found his spiritual home in Christianity.In recent years authors like Norman Wirzba, Bill McKibben, and Scott Russell Sanders have written about the relevance of Biblical texts for thinking about ecology. To me, they have been a little like St Ambrose. I've found one passage in Sanders to be quite helpful personally as I think about the management of my little suburban fifth-acre plot.

In his A Conservationist Manifesto, Sanders writes about the story of Noah and the Ark. He remembers that Noah was given the task of saving not just himself but every other species as well. And once they were on the ark, it was his job to care for the animals and to keep them alive. Sanders talks about books, and communities, and practices that can be like small arks in our time. One such "ark" may be the little plots of land we maintain around our homes:

"Every unsprayed garden and unkempt yard, every meadow, marsh, and woods may become a reservoir for biological possibilities, keeping alive creatures who bear in their genes millions of years; worth of evolutionary discoveries. Every such refuge may also become a reservoir for spiritual possibilities, keeping alive our connection with the land, reminding us of our origins in the green world."(2)Lately I've been surveying my yard more closely, looking to see whom I'm sharing it with, and how. I've been trying to do some phenology, like Thoreau did. I also wander my garden with lenses: a hand lens for close inspection; my phone camera and my SLR for keeping records of what lives and grows there; and I've recently set up an infrared game camera to see who passes through at night. For the curious, I've posted some photos below of what I've seen there.

*****

(1) Augustine, Confessions. Henry Chadwick's translation. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998) p. 88.

(2) Scott Russell Sanders, A Conservationist Manifesto. (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2009) p. 16.

*****

All of these images were taken by David O'Hara in the fall of 2013. You may use them elsewhere but please mention where you found them and give credit where it is due. Thanks.

Against Grading

We are sick with love of enumeration. We've discovered that counting things over time is a powerful way to predict what will happen next. And now we are mantic-obsessives, (that's not a typo) that is, people obsessed with prediction, with foresight that will rule the uncertainty of our lives.

Look: that's not such a bad thing, in a way. What I'm describing is the root and trunk of science: quantification and statistical analysis is the beating heart of our understanding of scientific laws, which are about predictive inference. Understanding of the laws of nature can save lives, and make water clean, and heal some deep wounds. Science is wonderful, and no liberal education should stint in its science offerings.

But if we're not careful - if we divorce science and enumeration from other ways of regarding value - that can make some pretty big holes in the world, too. (Whenever I hear someone say that religion is the cause of human suffering, I think "What about chemistry?" Both religion and chemistry can be deployed to change lives, and to change them dramatically. Or to end them suddenly.)

Likewise enumeration. The counting of things can give us great power to rule our own futures. It can also give us great power to rule the futures of others, and not always in kind ways. One real danger of learning to count things is that we find it too easy to shift from saying "It's hard to count X" to saying "X doesn't count."

Our quantifimania, for instance, has half of us (no, I didn't count, I'm speaking figuratively) believing that good teaching can be measured by test scores. Or that someone's intelligence can be reduced to a simple number. Or that a kid's giftedness, or ability to learn, or likelihood of living a creative and thoughtful life can be simply reduced to a GPA or a standardized test score.

Years ago, when I was thinking about beginning my graduate studies in Philosophy, a professor I knew suggested I prepare for my Ph.D. by attending St John's College's "Great Books" program. I looked over the reading list and realized that even if it didn't get me into a Ph.D. program, it would be worth it for its own sake.

As an undergraduate at an elite liberal arts college in the northeast, I was continually reminded that little mattered more than my grades. I was the sort of student who earned good grades with little effort, so it was natural to begin to believe that what mattered most came without struggle. As a result - I realize this now, in hindsight - I bypassed much of the opportunity my college offered me by studying only what my classes required of me.

This all changed in my first term at St John's, when I wrote a seminar paper on Aristotle. My tutor Matt Davis returned it to me without a grade on it. Instead, it was covered with marginal comments, underlining, and a paragraph of reflection and response at the end. But again, no grade. "How did I do?" I asked him. "Have a look at what I wrote," he replied. Sure enough, he told me how I did: here were the things that were strong; here were the gaps in my argument. No quantification, just explanation.

I wanted a grade because I'd been habituated to thinking of the grade as the way of judging the merit of my work. St John's decision to refuse to give grades is an intentional and hard-fought resistance to that way of thinking.

At the end of the term, each of my tutors gave me one, two, or even three pages of handwritten comments on my strengths and weaknesses as a student. But once again, no grades. Nothing to distract me from reading their comments, nothing that would allow me to measure the worth of their comments other than the comments themselves. And nothing to make me think: "Well, that's done."

As a result, I stopped thinking about grades and started thinking about ideas, and texts, and writing. I started caring more about correcting my ignorance than about concealing it from my peers and teachers. And I stopped thinking about learning as something that happens in fifteen-week segments. Learning was no longer something that begins here and ends there. Learning was now a river I step into, and in which I may swim, and bathe, and drink for as long as I am able. And if I step out, it remains there, ever flowing, for me to return to.

It was only then that I realized just how bored I had been in school. I had been bored since my childhood, because I had to show up, had to perform tasks, in order to get these lofty numbers that weighed so heavily and meant so little to me personally.

I've known many students who are bright but who don't do well on standardized tests. I've known many others who don't do well on any test at all, and I've no doubt that much of it has to do with anxiety over the way their work will be reduced to a number, one they feel is so disconnected from what they know. As a teacher I feel I'm constantly fighting to get my students to stop worrying about their grades, even while I'm required to assign grades to their work. Grades are, in my opinion, one of the worst things to happen to education. This is not to say I'm against evaluation or helpful feedback. I'm all for them, in fact. Which is why I'm so opposed to the damnable, lazy practice of reducing that evaluation to what can be easily counted.

The ancients tell us that King David sinned against God by counting his fighting men. (Here, too.) I think the sin was not the counting, but the way his counting became a basis for policy, and so for value. When we weigh our forces before going to war, the question shifts from "Is this a war worth fighting?" to "Can I win?" Both of those are important questions, but God save us from ever making the latter so important that we think of the former as a question that doesn't count. That kind of thinking turns people into instruments of war rather than free individuals; people become pawns, tools of policy, and they become as expendable as they are enumerable. When we dare to quantify our gains and losses in terms of numbers of human lives expended, we have already lost something important that may be very hard to regain.

And God save us, likewise, from thinking of our lives as things to be measured, and measured against others' lives. God save us from thinking of meaningful work as something to be done against a time clock, from thinking of wealth as something to be measured in numbers rather than in a richness of life. And God save us teachers and citizens from thinking that the worth of a woman or a man can easily be measured by the grades they have earned, or that the predictions we may make on the basis of those grades should have the power of prophecy.

Because "Liberal" in "Liberal Arts" Means "Free"

Martha Nussbaum, Not For Profit: Why Democracy Needs The Humanities. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010) p. 21.

An Ounce Of Prevention

I've lost track of how many times I've heard someone say recently that the point of the Second Amendment is, first of all, to safeguard the other rights enumerated in the Constitution, and second, that a well-regulated militia is necessary in case we ever need to overthrow a government that has turned into a tyranny.

I have a little (though not much) sympathy with the second of those positions, but the first is, I think, simply wrong. Here's why: the First Amendment is itself an extremely powerful tool, and it is fitting that it should precede the Second, because an attempt to solve problems by reasonable words should always precede the attempt to solve our problems by force. In other words, if we exercise our First Amendment rights responsibly, we will never need to invoke the Second to overthrow our government. One of the beautiful things about our Constitution is the way it provides means for us to address unjust power grabs by our government officials without starting an insurrection.

But the bigger problem is one of what fills our hearts and minds: Focusing our attention on preparing to overthrow a future tyranny is like a physician preparing to euthanize a patient who might someday become ill. Yes, it is possible to "cure" any illness by killing the patient, but it's not good medicine. We need more than just preparedness to kill a disease; we need to promote good health as well.

If you're concerned about the nation becoming a tyranny, buying more guns is a poor response. Here are some far better responses:

* Thomas Cleary tells this story in the translator's introduction to his edition of Sun Tzu's The Art Of War (Shambhala: Boston and London, 1988) p. 1.

Scholia, Essays, and Education

|

| (White space, refracted) |

In an earlier post I spoke of the pleasures of finding marginalia in others' books, and of writing one's own marginalia. The word "marginalia" means, of course, "things [written] in the margin." In a way, the aim of education is to prepare us to write our own marginalia.

We set aside places for education, and these we call "schools," from the Greek word scholé, meaning "leisure." Most students don't think of schools as places of leisure, but it is only a person with leisure from menial daily work who has the leisure for school.

That word scholé is also related to the word scholion (Greek) or scholium (Latin). Those words mean "a comment." The act of reading is not complete with seeing the words on the page; we have read a text when we have observed it, worked to understand it, and then contemplated its meaning for our own lives. Looking at words without reflecting on them and then calling it reading is like looking at a menu without eating a meal and calling it "going to a restaurant." Technically true, but not at all nourishing.

Those with leisure to read books also have the leisure to reflect on books and on what they mean for us. When that reflection takes the form of scholia (the plural of scholion and scholium) - that is, when we write comments on texts, the writing is an attempt to complete the act of reading. So when we teachers assign essays we are (ideally) not assigning writing so much as reading. The aim is not a polished essay; the polished essay is merely the sign of something else. The aim is reflection on texts. The word "essay" comes from a French word meaning "attempt, try"; each essay is an attempt to become a little better at observing texts, at understanding what they mean, and at articulating what they mean for us.

Books Worth Reading

I'm reluctant to make book recommendations because I think what you read should have some connection to what you care about and what you've already read. In general, my recommendations are these:

First, I agree with what C.S. Lewis once said:* it's good to read old books. Old books and books written by people who are not like us have a remarkable power of helping us to see the world with fresh eyes.

Second, let your reading grow organically. If you liked a book you read, let it lead you to the next book you read. Often, books name their connections to other books. Or authors will name those connections, dependencies, and appreciations. The first time I read Lewis's Out of the Silent Planet, I missed the fact that the preface named H.G. Wells and that the afterword referred to Bernardus Silvestris. When I read it again as an adult, I caught those obvious references and let them lead me to other books.**

Third, I recommend learning the classics. That's an intentionally vague term, and I use it to mean that it's good to know those books that have given your culture its vocabulary. People who have stories in common have enriched possibilities for conversation. One of my favorite Star Trek episodes explored this idea, and it appealed to me because I believe that it's not far from how language really grows. If you need a place to start, check out one of the various lists of "great books" floating around out there. For instance this one, or this one.

With all that being said, if you're still interested in what I'm reading, here are some older titles I've enjoyed in the last year or so:

* Lewis said this in his introduction to Athanasius' On The Incarnation (which, by the way, is now available from SVS Press in a dual-language edition, Greek on one page, English on the facing page.)

** There are two excellent books on Lewis' "Space Trilogy" or (as I think it should be called) "Ransom Trilogy": This one by Sanford Schwartz, and this one by David Downing.

Shakespeare's Sonnets, And Rieden's "Sonnet Number Six"

The Dean listened to all this patiently, and then made Charles an offer: write me one good sonnet and you don't have to read any of Shakespeare's sonnets. Charles immediately agreed. How hard could it be to write one decent sonnet?

Very hard, it turns out. And Charles, to his everlasting credit, came to see that pretty quickly. He produced some sonnets that week, but, by his own estimation, they were terrible. So he kept trying. Eventually, over the course of the next year, he had a thick stack of sonnets. I think in the end he wound up writing more sonnets than Shakespeare, and quite a few of them were really good.

Charles died, tragically, later that year. He was hit by a drunk driver as he walked along a highway in Santa Fe. The college framed one of his best sonnets, "Sonnet Number Six," and hung it in the graduate student common room.

As near as I know, it still hangs there, a memorial to Charles. I take it as a reminder not to dismiss too quickly what I do not understand, and not to imagine I understand what I have not really engaged with.

Great Books, Pedagogy, and Hope

About fifteen years ago I enrolled in the "Great Books" M.A. program at St John's College in Santa Fe, New Mexico. It was one of the best decisions I've ever made.

Much as I appreciate my undergraduate education, too often it rewarded me for concealing my ignorance and emphasizing what I already knew. The problem, of course, is that my ignorance was thus shielded from the sterilizing sunlight of others' scrutiny and instruction.

Confessing Our Ignorance

Matthew Davis, my tutor and advisor at St John's, won me over to another way of viewing literature when, on one of the first days we met, he pointed to a passage in Plato's Republic and said "I have always wondered what Plato means by that." Looking up at the class, he asked, "Do any of you have any ideas about what he might be trying to say?"

Mr. Davis is the first professor I recall who openly confessed his ignorance, and who thereby modeled what it means to open oneself to the instruction of a great text. Not much has shaped my academic life as much as that.

Grappling With Classic Texts

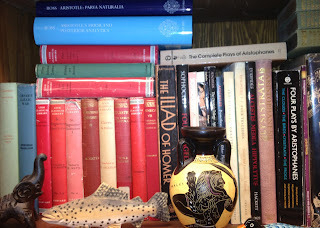

As I have begun to mature into my own place as a teacher, I often think that this is the best thing I can give my students: not professorial and authoritative descriptions of texts, but an example of what it means to be a student. I can try to be an example of someone who sits with texts and listens to them, grappling with them, like Jacob with the angel or like Menelaus with Proteus: persistently grappling with my superior and refusing to let go until I receive a blessing. (Selah.)

For the last few years I have been seeking out and reading classic novels. As I read them I feel like an apprentice architect touring buildings, looking not just at the outward form and function but looking for the supporting structure, trying to notice the decisions the artist made about what to include and what to omit.

Along the way, I have begun trying to write bits of dialogue, scenes, characters, and other elements of fiction. I'm not trying to write a novel so much as trying to perform experiments the way high school science students do in labs: not to discover something new but to learn haptically, kinesthetically, experientially what the masters already know. I can't say that I've learned to write novels, so don't expect anything from me there. But as I've paid attention, I feel I've begun to squeeze some blessings out of the books, including some unexpected ones.

I've noticed, for instance, that Craig Nova writes about the olfactory sense in a way that makes me notice aromas I never noticed before. John Steinbeck has begun to make me care more about friendship, and about the people in front of me. Harold Frederic has me rethinking my early faith, and this is helping me look ahead as I try to nurture it into a faith worth having. Novels are helping me see the world differently.

So What Does This Have To Do With Hope?

I just finished Graham Greene's The Honorary Consul. Apparently this was Greene's favorite of his own works, and I can see why. Like many of the really good novels I've read, it has left me thinking about a range of topics, and longing for someone to talk about it with.

Which brings me to hope. I started reading Greene because Bill Swart, my friend and colleague, told me about how good Greene's novels are. Bill was right about this, so I sought him out the other day to talk more about Greene. We said too much to cover it all here, but Bill said something I can't bear not to repeat. When we began discussing Greene's The Power and the Glory, Bill said "That book gave me hope that my own self-perception might be wrong."

If you know the novel, you know why, because you know how Greene's characters wrestle with being both sinners and saints. If you don't know the novel, let me recommend it to you.

We Should Keep Teaching And Reading Fiction

I still have a lot to learn about novels. I doubt I'll ever write one - or a good one, anyway. But I'm delighting in reading them. Perhaps that's why they matter so much: they delight us, and capture us. When I'm in a good book I feel like I'm really in it. I stop seeing words on a page and start seeing, with some inner eye, the world the novelist sees.

And like all my other travels, journeys into fiction leave me a different person. I see different possibilities, I see -- and smell -- my world differently. I know it's important to teach young people to read non-fiction, but teaching fiction might be for them what The Power and the Glory was for Bill: a tonic for his soul, a sweet drink of hope that didn't just entertain, but that allowed him to envision his life, his work, and his purpose in an entirely new way.

Contemplation, Conversation, Commentary

To paraphrase Plutarch’s famous line about education, the mind is not a vessel to be filled but a fire to be kindled. A jar that is filled by someone else only contains what is put into it; it becomes a place of storage. It is a useful tool, but it does not increase what it holds. A fire, on the other hand, gives off heat and light, and that heat and light can kindle other fires and illuminate distant obscurities.

I think education should be like this, a process that pays continual returns if it is well tended.

Of course, unchecked fire can do great harm, and education without boundaries is like a fire with no hearth or stove.

Should Education Have Boundaries? A Reflection On My Own Classrooms

But how can we put boundaries on education? One way, of course, is to limit education to memorization, tool-and-skill training, or indoctrination. But each of these amounts to filling a vessel. That is, it amounts to filling students’ minds with facts, opinions, or skills, without giving the students what they need to examine or improve what they are given, and to teach others what they have learned.

My aim as a teacher is to offer students liberal arts in such a way that they gain both practical skills and the means to improve those skills as the use and teach them. I say liberal arts because I do not wish my students to be the servants of others, but to be people who practice responsible liberty and who help others to do the same.

Of course, unchecked liberty can do great harm, and liberal education without boundaries is like a fire without a hearth. In one direction lies the restraint of being the mere vessel of others’ doctrines; in the other direction lie the perils of life beyond the bounds of ethics.

Fortunately, this is not a new problem, but a very old one. This means that there are some old and time-tested means of education that help us to find the mean between the extremes.

What I try to practice in my classes is something I see – in varying degrees – throughout the history of education. I will summarize it in three words: contemplation, conversation, and commentary.

Contemplation

By “contemplation” I mean the practice of examining what is already understood by the community of inquiry. What do we know? What are the tools we have at hand? What are the problems we wish to pursue together, and what solutions have been put forward so far? Learning these things is the first step, akin to learning the language when you move to a new country. It involves some memorization, and it involves learning the rules by which others conduct their lives and research. This is like learning the basics of a science, plus the methods used by scientists; or it is like learning the basics of poetry, plus the methods of reading and writing. Each discipline has its content and its tools, its history and its methods, its canonical texts and its rules and rituals for learning those texts. In my philosophy classes this means reading the assigned texts thoughtfully so that you come to class ready to ask good questions about them. In my language classes it means working through grammar and translation exercises, and memorization of vocabulary and inflections. In my environmental studies classes, this means learning basic taxonomy, ecology, geology, law, and policy, so you can discuss these things with others who know more than you do. In each discipline it will involve different things, but the general rule holds: if you want to join the community, you’ve got to learn these things first, just as you have to learn grammar before you can converse with others. And conversation is the next step.

Conversation

By “conversation” I mean coming together with others to think about the rules and tools we have been given. This is more than speaking with friends; this involves serious grappling with issues in the company of our contemporaries. In my philosophy classes, this means asking good questions about what you’ve read the night before class. It means exposing your ignorance and asking others to help you to correct it. It means taking others seriously as people who might see what is hidden in our blind spots. In my environmental humanities classes, this means going into the field with your classmates in order to examine the world together. In my philosophy of religion classes, this means engaging in the hard work of talking about the divine in a way that takes others seriously. Their questions might just be the questions you need; their insights might serve you well. It would be unwise to decide in advance that others have nothing to teach you; in each discipline, you’ve got to take time to do research, whether in the lab, in the field, in convivial conversation and deliberation with others. And then, when you’ve done that well, you’re ready to offer commentary on what your new insight means for us all.

Commentary

This is what I mean by “commentary,” then: the slow consideration of what consequences we might expect from what we have learned so far, and the offering of that consideration to others, so that they can contemplate and deliberate on them, and offer new commentary of their own.

Learning As A Cycle, And As A Shared Process

If you’ve done a good job with the first two steps, the third step leads you back to the first step. Good researchers who publish what they have learned contribute to the body of knowledge that others can use to kindle new fires that warm new homes and light new paths.

Another way of thinking about these three steps is that it concerns thinking about different times. The first step is the consideration of the past; the second involves taking seriously the present time and our contemporaries as fellow learners; and the third step is mindful of the future.

You might also think of this as a process of thinking at different speeds, and from different perspectives. The first step is often quite slow at first, and it requires us to learn to see as others saw, even if their way is not our own. The second step might happen quite quickly, whether in a sudden insight in the laboratory or in a fast-paced debate. The third step often requires the very slow work of painstakingly careful thinking and clear writing.

Of course, these three steps are not discrete. Often, they overlap and intermingle. We might discover in debate or in the field that we have failed to learn something important. Or our contemplative work might send us back to reexamine our research, or even to start over with new tools and insights. But on the whole, I think these three facets of learning wind up being repeated over and over in each field, and by connecting us to other people in the past, present, and the future, they offer a sort of bounded liberty to our learning.

Slow Thinking, Quick Writing, and Slow Assessment: On The Importance Of Self-Discipline

Much of what I hear and read about education has to do with metrics intended to assess the value of certain kinds of practices. I see the merit in many of those metrics. Sometimes, though, it seems that the metrics become a quick substitute for other kinds of evaluation that are harder to put into numerical or measurable form. We don't like the slow process of contemplation, or of commentary. We do like it when others put things in simple forms that we can quickly compare. There's value in that, but if we don't do our own contemplation and commentary, we abdicate a good deal of our involvement in our own learning, and we shift from being fires to vessels.

I am writing this piece fast, because I have a discipline of trying to write all my blog posts in less than fifteen minutes. (I do sometimes return to them to edit them for clarity or to add relevant information.) My aim here has been to write quickly about something I have thought about slowly. In other words, I've contemplated this for years, and today I'm writing a bit of quick commentary to contribute to our shared conversation. My quick writing is intended to be a moment of distillation of a cloud of contemplation. Too much time with my head in the clouds can obscure my vision; at some point I need those clouds to precipitate into more concrete thoughts. Writing helps me to do that.Your thoughtful replies and insights will hopefully help to kindle new fires.