Liturgy

- How can I begin and end each day so that each day has a sense of being meaningful?

- How can we begin and end each week so that toil does not become the pattern of every waking moment?

- What are the times of year that give themselves to fasting and mourning, feasting and celebrating, so that we can meaningfully reflect together on the real wounds, and lament together over what we’ve done; and so that we can rejoice together convivially, eating, drinking, and being merry in the wounds that we have worked together to heal.

- fasts with feasts,

- days of rest with days of labor,

- celebration with food,

- the progress of our days with the progress of the skies,

- remembrance with anticipation,

- rejoicing with mourning.

Word of the Day: Stammtisch.

Word of the Day: Stammtisch.

A Stammtisch is a table for regulars at a coffee shop or restaurant. It names not just the table but the idea.

There’s something powerful in having a place where you regularly gather with others, a “third place” besides work and home. A lot happens at the water cooler, at the scuttlebutt, at church coffee hour.

Interestingly, many species of animals around the world have something like family reunions. Regular gatherings that reinforce bonds and serve to pass on knowledge to new generations.

We all benefit from the same thing. I’ve read of epidemics of loneliness; breaking bread with others might not be a cure-all for that, but I doubt it could hurt.

It probably shouldn’t surprise us that so many religions have gatherings around something similar: simple meals taken together as a community. As simple as bread and wine, or three palm dates.

I love learning new words, and hoarding them for my writing. I keep a file of good words, and try to include them in everything from my academic writing to my texts. If you’ve got some good words to share, I’d love to learn them!

Philosophy of Liturgy, and Climate Grief

I admire Greta Thunberg for her passion and commitment. I similarly admire a number of my students for their constant concern for the environment. This world we share, “this fragile earth, our island home,” as the BCP calls it, should not be mistreated.

And it is being mistreated, by all of us.

The more you know about that, the more you feel as Greta seems to feel, and as Aldo Leopold felt, like someone who “lives alone in a world full of wounds.” In his book, Round River, Leopold wrote that

“One of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives alone in a world of wounds. Much of the damage inflicted on land is quite invisible to laymen. An ecologist must either harden his shell and make believe that the consequences of science are none of his business, or he must be the doctor who sees the marks of death in a community that believes itself well and does not want to be told otherwise. The government tells us we need flood control and comes to straighten the creek in our pasture. The engineer on the job tells us the creek is now able to carry off more flood water, but in the process we lost our old willows where the cows switched flies in the noon shade, and where the owl hooted on a winter night. We lost the little marshy spot where our fringed gentians bloomed. Some engineers are beginning to have a feeling in their bones that the meanderings of a creek not only improve the landscape but are a necessary part of the hydrologic functioning. The ecologist sees clearly that for similar reasons we can get along with less channel improvement on Round River.” --Aldo Leopold, Round River, Oxford University Press, New York, 1993. p.165When we hear of a single wound, most of us offer to help mend the wound. Most of the people you meet are, after all, people of good will, people who love their friends and families and who want the best for their community.

When we start to hear of more wounds, we react differently, wondering what we can do to protect ourselves from being wounded.

And when we find that there are wounds everywhere, it’s overwhelming. Some people react by plunging into grief. Seeing that the world is in peril, they wonder why no one else sees the peril, or cares about it. The problem is immense, the resources to cope with the problem are few, and lamentation quickly becomes fragile despair.

Others enter a state of denial, or of resignation. That’s just how it is, they say. It’s the price we pay for progress, and we can’t go back. There is nothing we can do but move on and hope for better solutions in the future. Eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we might die.

Thing is, they’re both partly right.

The world is in peril. And the wounds are too many for any one of us to heal on our own today.

A liturgical calendar can help.

The Book of Ecclesiastes offers some helpful words: There is a time for everything under heaven. A time to heal, a time to rejoice, a time to mourn, a time to gather stones, and a time to cast stones away.

We need time dedicated to climate grief. This is like Lent, or Ramadan, or Yom Kippur, a time of fasting, of reflection on what we have done wrong, of repentance and turning away from our errors, of atonement. These are times for pausing to consider our lives and our connection with others. Lamentation of error is essential for learning to do better.

We also need time dedicated to hope. For every fast, there should be time for feasting. We need both the thin seedtime and the fat harvest. Just as we need to mourn our own ignorance and error, we need to celebrate the good things that are still worth seeking, striving for, and preserving.

Most people know the names of a few holidays. Few know the reasons for the holidays, or why they have lasted for so many centuries.

I’ll suggest that whatever tradition lies in your heritage or in the heritage of your community, take a little time to consider it. What rituals of fasting and feasting, of mourning and celebrating does it offer you? Religion is not without peril, of course, but it can also be a rich inheritance if you know what to do with it.

As you consider the liturgies you’ve inherited, remember that most ancient liturgical calendars follow the patterns of the heavens above. I don’t just mean that in some mystical sense (though there’s probably more there than we can easily grasp) but in the simplest sense: liturgical calendars follow days, weeks, months, and years.

It can be helpful to ask questions like these:

Commerce, Environmental Attention, and the Liturgical Calendar

|

| Bighorn sheep in the Badlands National Park. The animals move together, responding to the land. |

By "liturgy" I mean the work we do together on a regular basis. The word "liturgy" comes from two Greek words that mean "the work of the people," and it usually refers to the rituals of worship in a religious congregation: it's the formula for when and how and where we stand, sit, kneel, pray, etc.

Most religions I can think of have liturgical calendars that describe the regular cycle of rituals in a year. If liturgy usually refers to what we do when we gather for a holiday or a day of worship, a liturgical calendar organizes the year so that we know when those days occur. It usually gives a sense of the flow of time, connecting days to one another with some purpose: liturgical calendars connect

|

| Watching the seasons change: autumn leaves make imprints in the ice on my campus green. |

I used to think this was all silly, and a forced imposition on my freedom.

Lately I've been discovering that -- for me, at least -- the calendar's structure is a source of freedom from other calendars that don't help me to live well.

When I was younger I abandoned the liturgical calendar because I didn't want someone else telling me what days were holy. Why shouldn't they all be holy if I want them to be? And why should I fast just because someone else said we all should fast?

What I've come to see lately is that If we abandon the liturgical calendar with its times of feasting and fasting, the calendar doesn’t go away; it just becomes commercialized and turned into a calendar of constant consumption, constant labor. Feasting becomes purchasing; fasting becomes debt; and the two coincide with no time of rest between.

I experience the collapse of the calendar most where people like me have given it up and allowed others to co-opt it for commercial purposes. In simple terms, I experience it when I walk into a store in October and I hear Christmas music. All around me are ads telling me that my greatest obligation is to purchase things for Christmas, and to do so now.

This makes me want to shout: please spare me the Christmasy jingles, most of which drive me from your store. I like Christmas hymns, but the stress of being a cog in the machinery of holiday commerce has led me to appreciate the difference between Advent (a season of anticipation, of watching, and waiting) and Epiphany (a season of revealing, of celebration of birth, of discovery).

No one taught me this when I was young, but I've learned over the years that my tradition has different hymns for different times in the liturgical calendar. Now it feels odd to enter a pharmacy and to hear a hymn for the Nativity being played over the loudspeakers during Ordinary Time.

I used to think all that tradition to be nonsense. The older I get, the more I appreciate the thoughtful progress of a year, and the more I dislike the flattening of all days and all times into a yearlong, nonstop worship of commerce and toil.

We can't easily escape liturgical calendars, and I'm not sure we should. Even the birds of the air know when it is time to migrate, and they all have their liturgy of flight. The flowers know when to bloom, the salmon know when to spawn, the bears know when to look for the salmon. We humans used to know all these things, too.

Little by little we have lost connection to the liturgies that connect us to the land, the plants, the animals, the water, the wind, and the skies. When I ask my students what the phase of the moon is, it's rare that they know.

And I admit it is a wonderful thing not to need the moonlight. Running water, grocery stores, central heating, a solid roof, a functioning car, and many other modern conveniences are delightful. But they do come with costs; these good things are not free. They cost us money, which means we work more for them. And they have invisible costs, like the slow change of the quality of air in cities, the slow degradation of the planet's water, the slow loss of species around the world, the slow accumulation of things we throw away.

And then, when these slow processes pile up, we begin to notice them, and we begin to wonder: what have we done? We slowly gave up the liturgies of seedtime and harvest and replaced them with liturgical calendars in which all days are days of commerce and toil.

Which gives rise to new liturgies, urgent liturgies of anxiety. Look at what we have done, we say. With sackcloth and ashes we lament the fouling of our nest. As an environmental researcher, I see the fouling clearly and often, and I share that stress, that anxiety, that lamentation.

But if we replace the new liturgy of constant toil and waste with a newer one of constant lamentation over the toil and waste, we might wind up replacing one flattening of days with another.

|

| Seedtime leads to harvest, and then seedtime again, with times of rest in between. |

I don't know the solution, and I don't intend to argue for returning to some halcyon past. Nor do I plan to argue for the imposition of my chosen calendar on others. But I do intend to reexamine the calendar I inherited, to dust it off and see what I missed when I put it aside. Sometimes old ideas are still good ones; some old seeds can still bear new fruit.

For now, what I propose is to mourn in some seasons, but also to rejoice in others. If there is mourning to do, it is also the case that there is still life to preserve. Each of these things--mourning and preserving, looking back at what is lost and looking ahead to what might flourish--calls for its own day. And each day calls for a calendar that can connect it to the other days in a way that keeps each day from dissolving into atomic time. Each day has some part of the whole of life. That part is worth seeing in its own day.

Searching For Winter Strawberries

|

| A late October strawberry in my garden |

One day in February, for no particular reason, I wanted to eat strawberries. A few blocks from my flat there was a market, so I walked there and searched for fruit stands. Finding one but seeing that they had no strawberries, I asked the proprietor, "Do you know where I can find strawberries?"

"Of course," he replied. "Right here."

"But you don't have any," I observed.

"Of course I don't," he said.

I was confused. "But you said I could find strawberries right here."

"You can," he replied. "But not until June."

This took a little while to sink in. I was accustomed to going to a supermarket at home in New York and buying any fruit I wanted at any time of year. Now I was being told what should have been perfectly clear: fruit is seasonal.

At first I was disappointed, but it took only a few minutes before I realized that this wasn't such a bad thing. It meant that the strawberries, when they arrived, would taste that much sweeter. The disappointment of having to wait would be repaid by the delight when they did arrive.

The experience didn't reform me, of course. I love eating my favorite foods year-round, despite not having harvested them and usually without knowing where they came from.

But it did make me appreciate some of the rhythms of life around me. The first part of Aldo Leopold's A Sand County Almanac, and most of Thoreau's Walden - two of my favorite books - follow the cycle of the seasons in the northern part of the United States. Their understanding of nature is one that allows nature to undergo its habitual changes. They might even say that what they know about nature arises from attention to just those changes. Phenology, the attention to when and how things appear and disappear throughout seasons, is one of the most important parts of learning to see the world. If I may speak an Emersonian word, phenology attunes us to the music nature wants us to hear. To speak less mystically, it accustoms us to natural patterns, and much of what the naturalist wants is to learn those patterns so well that we can then see when nature departs from them.

What are the calendars in your life? Technology has made many of them seem unnecessary, but I suspect that they give us much more than we know, just as my experience in Spain gave me unlooked-for lessons. We should be careful not to insist that others delight in the absences or disciplines we delight in; what may be a delightful, self-imposed fast to us may be devastating to someone who is genuinely hungry. When we choose them for ourselves, school calendars, planning one's garden, the liturgical calendars and holidays of the world's religions - each of them can offer us rhythms of both discipline and delight as we make ourselves wait for the strawberries to ripen, the hummingbirds to return, the exams to end, the candles to be lit.

Secular Liturgy

But I've found I need liturgy in my life. Liturgies help me mark seasons. More than that, liturgies create seasons. That's what I really need, because the creation of seasons becomes, for me, a discipline of memory.

Liturgies help me to count my days, which in turn helps me to make my days count.

I used to chafe at the remembrance of birthdays. Why should one day count more than any other? And why should one day seem more a holiday than another?

I'm slowly getting it. There is nothing special about the day; what is special is the use of the day. Cheerless debunkers never tire of pointing out to me that western Christmas is celebrated on a Roman holiday, that Easter is *really* some kind of fertility rite because it's celebrated in the springtime, that all my holidays don't mean what I think they mean because someone once celebrated them in another way. As though the genealogy of the holiday should be its only meaning, as though the celebrations of the past should have magical power over me, as though I had no power to make the days mean something new to me.

And it is true: holidays and liturgies do have power. As I have said before, what we cherish in our hearts we worship, and what we worship we come to resemble or imitate. Holidays are always about remembering, and remembering is cherishing. Of course, we don't all cherish the same things. Memorial Day is, for some, a remembrance of valor and sacrifice. For others, it is a good day for a picnic with family. Both are forms of cherishing, though the thing cherished is quite different.

Much of the difference probably comes from mindfulness and intention, or lack of intention. Everyone cherishes something, but not all of us think about what we cherish. Liturgies help me to cherish mindfully.

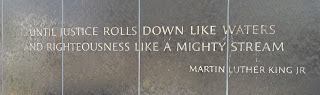

Which is why every April 4th I read or listen to Dr. King's "I Have A Dream" speech, and weep at his loss. And why every July 4th I read the Declaration of Independence. I have set aside days in my year, every year, to read texts like these, texts that have shaped my community. Because these texts aren't done with their shaping. Texts don't hit us once and do all their work; texts seep into us, their words become our words.

Reading and re-reading and reading aloud in communities - these things are like the pouring of water through leaves or grounds - the reading percolates through the words and picks up the essential oils, the savor, the color and taste of the text, and delivers it to us like tea or hot coffee. We taste the words and then the words enter our guts, our veins, our souls.

I recently read an interview with a woman who said "I don't need to go to church to believe those things," referring to her church's beliefs. True. Just as I don't need to go to the gym to get exercise, or to believe that exercise is good for me. But if I don't make a habit of getting exercise, I find I tend not to get what my body needs. The urgent matters in life so easily overwhelm the important ones. Often, when I return from the gym, my wife asks me "How was the gym?" I always think, "It was hard. Everything I do at the gym is difficult." But it is worth doing, because it helps me to maintain my health, and to fight my own decline, to fight the slow slipping away of what I want to hold onto as long as I can. If I do this for my body, why should I not also do it for my heart and mind?

|

| The words percolate through us, and enter our veins. |

I'm not writing this to endorse all liturgies. I'm confident that there are liturgies that celebrate awful things, and that there are participants in liturgies who make poor use of the liturgies they sit through. As with most of what I write here, I'm trying to sort out what I believe, and why -- as another kind of discipline, one of remembering, and of being mindful of what I believe.

The liturgy of Maundy Thursday is not an easy one, because it reminds me of two things I am capable of: I am capable, like Jesus, of washing others' feet, and of living a life of love; and I am capable, like Jesus' friends, of betraying those people and ideals I most claim to cherish and worship. If my worship is only worship in words, I find it easy to forget to worship what is best with my body, with my life. Liturgies - and we all have liturgies - are the ways I remind my whole person to stop and remember what my words claim so easily to believe.

Reading the Holidays

This practice of reading the holidays began for me about ten years ago on July 4th. I decided then that I'd re-read the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution. I was guessing that it had been so long since I'd read them, I'd probably forgotten much of what they say. My experiment proved my guess to be right.

I was struck, as I read them, just how remarkable these documents are. Since then, I've repeated this almost every year. Each time I re-read these documents, I find them moving. They're beautifully written, and they strive for things that are, in my estimation, praiseworthy.

I've begun to add other readings for other holidays as well. On MLK, Jr. Day, (and sometimes on April 4, the anniversary of his death) I listen to his "I Have A Dream" speech or read his "Letter from a Birmingham Jail." I admit it: both of these regularly make me cry.

Of course, I also read the appointed Scriptures for Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost, and for some other feast days as well. But here I'm interested in those holidays that are not holy-days but secular feasts. How about you? Do you have readings you associate with such holidays? What do you recommend?

--------

* (If you're interested, you can see my article on Puritanism by clicking here and searching for pp 631-632)