love

- The passage from the novel is from Laura Ingalls Wilder, Little Town on the Prairie. (New York: Harper Collins, 1971) 198-199.

- The passage from Laura Ingalls Wilder's letter to her friend can be found here: LIW to Miss Weber, 11 February, 1952. Cited in Ann Romines, Constructing the Little House: Gender, Culture, and Laura Ingalls Wilder, University of Massachusetts Press, 1997. p.233.

- The economy of Nicaragua is closely tied to the economy of the United States;

- Many Nicaraguans have had to leave their family farms because cheap exports from the United States make it impossible to sell their produce and grain at competitive prices;

- Those who leave the family farm often fail to find work in the cities;

- One cause of this is that the work conditions in the cities are largely established and controlled by the international firms that can easily relocate to other poor countries if their requirements are not met. This keeps wages low, and makes it difficult for the country to receive any tax benefit from international industry;

- So capital freely flows out of the country and across borders;

- People follow the capital as it flows.

∞

Gracias, señora Orza

Estimada Sra. Orza,

One day when I was in middle school in New York you said to me “You’re good at languages. You should go to Middlebury.” I hadn’t heard of it before, and I had been planning to attend the cheapest local college I could attend, to save my family the cost of college. Then you handed me a brochure from Middlebury, about their summer language programs. A year later, when I was leaving to work in Nepal for the summer, you gave me a blank journal as a parting gift, reminding me that writing matters.

I haven’t seen you since then, and I haven’t been able to track you down to thank you in person, so I’m firing this out into the internet to say thank you to you and to all the other teachers like you. Why? Because you changed my life.

Three years after I last saw you, I drove to Middlebury to check it out, and I fell in love with the place. I sat in on a Religion class (a subject I thought I wouldn't find interesting at all) and learned more about religion in that single hour than I thought possible.

So I applied, and I got in, with a scholarship. I guess they thought I should go there, too! Over the next four years that college made it possible for me to study in Spain; to learn to read and translate multiple forms of classical Greek; to be exposed to history as more than names and dates; to study physics, and math, philosophy, and even a little more religion.

Looking back on those years now, I see that my whole career has arisen out of classes I took there.

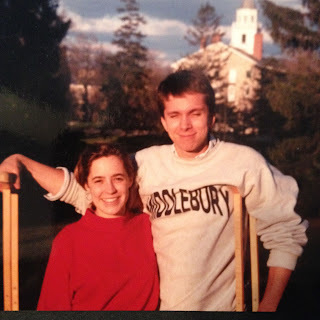

And best of all, I met this amazing woman! I think you’d like her. Like you, she’s smart and sweet. Like you, she encourages me to keep learning. And like you, she’s fluent in Spanish.

Far more than the classes, she has changed my life. So often it's the people you meet--and not just the things you learn--that change you. I'm grateful to have met you both.

So thanks for being a Spanish teacher in a middle school in rural New York. Thanks for putting up with all of us kids in your classes, year after year. And thanks for taking my future seriously enough that you thought that my life, my travels, and my studies really mattered. You saw all that far more clearly than I did back then, but over the years I’ve come to see what you saw, and I’m forever grateful.

Your loving student,

Dave

One day when I was in middle school in New York you said to me “You’re good at languages. You should go to Middlebury.” I hadn’t heard of it before, and I had been planning to attend the cheapest local college I could attend, to save my family the cost of college. Then you handed me a brochure from Middlebury, about their summer language programs. A year later, when I was leaving to work in Nepal for the summer, you gave me a blank journal as a parting gift, reminding me that writing matters.

I haven’t seen you since then, and I haven’t been able to track you down to thank you in person, so I’m firing this out into the internet to say thank you to you and to all the other teachers like you. Why? Because you changed my life.

Three years after I last saw you, I drove to Middlebury to check it out, and I fell in love with the place. I sat in on a Religion class (a subject I thought I wouldn't find interesting at all) and learned more about religion in that single hour than I thought possible.

So I applied, and I got in, with a scholarship. I guess they thought I should go there, too! Over the next four years that college made it possible for me to study in Spain; to learn to read and translate multiple forms of classical Greek; to be exposed to history as more than names and dates; to study physics, and math, philosophy, and even a little more religion.

Looking back on those years now, I see that my whole career has arisen out of classes I took there.

And best of all, I met this amazing woman! I think you’d like her. Like you, she’s smart and sweet. Like you, she encourages me to keep learning. And like you, she’s fluent in Spanish.

|

| We started dating in college, and we're still dating each other now, even though we're both married. I think you'd like her. |

Far more than the classes, she has changed my life. So often it's the people you meet--and not just the things you learn--that change you. I'm grateful to have met you both.

So thanks for being a Spanish teacher in a middle school in rural New York. Thanks for putting up with all of us kids in your classes, year after year. And thanks for taking my future seriously enough that you thought that my life, my travels, and my studies really mattered. You saw all that far more clearly than I did back then, but over the years I’ve come to see what you saw, and I’m forever grateful.

Your loving student,

Dave

∞

Reason For Hope

Nearly every spring term I teach a class called “Theology and Philosophy in Dialogue.” I inherited the title and the course description when I started teaching at my current school in 2005. Each year the course changes a little, in response to my students and what I perceive to be relevant themes in our world and culture.

Apologetics and Postmodernism

When I first taught it, I made it a class about apologetics and postmodernism. By “apologetics” I mean the work of giving a reasoned account of one’s commitments; by “postmodernism,” I mean the suspicion that what look like reasoned accounts might have unexamined depths and layers to them. In the context of theism—and in particular Christian theism—apologetics has a long history that reaches back to the early years of Christianity. Saint Peter wrote in his longer letter that Christians should always be prepared to give a reasoned defense of the hope they bore within them. That phrase “reasoned defense” is a translation of the Greek word apologia, which can mean a legal defense, and from which we get our word “apologetics.”

When Saint Paul of Tarsus found himself in Athens, speaking to Stoic and Epicurean philosophers on the Areopagus, he tried to explain his beliefs not in the terms of his culture but in theirs. He doesn’t seem to have won many over to his views that day, but if nothing else was accomplished, at the end of the conversation it was clearer where Paul and the Greek philosophers were in agreement and where they disagreed. If immediate conversion was the aim of his speech, it wasn’t a great speech. But if he aimed to build a bridge of mutual understanding, I’d say he was pretty successful.

One of the keys to his success, I think, was familiarity with the culture around him. I’ve written about this elsewhere, so I won’t belabor it here, but I’ll just point out that Paul quoted two Greek philosophical poets, Epimenides and Aratos, and he did so in a culturally appropriate and significant place, since several centuries before Paul’s travels, Epimenides (who was from Crete) also traveled to Athens and also spoke on the Areopagus about the gods and salvation.

Understanding Atheism(s)

A few years after I started teaching that course, I shifted the course to take seriously the “New Atheists.” I figured that if my religious students graduated without hearing the strongest challenges to their faith, I, as a professor who teaches theology, was letting them down. I wanted them to know that soon they’d hear strong arguments against their religious heritage, beliefs, and practices, and that these arguments should be taken seriously. For my Christian students, I framed this as a way of living the commandment to love God with one’s mind.

Of course, only some of my students are religious, and some of the religious students aren’t Christians. (I’m at a Lutheran university in a small Midwestern city, so until recently most of them were at least culturally Christian; that’s changing quickly, though.) I wanted this to be a class that was helpful for everyone, so I started to turn this into a class about mutual understanding. I now teach my students how to distinguish between a dozen different kinds of (and reasons for) atheism, lest they make the mistake of oversimplifying the complexity of their neighbors and of themselves.

Understanding and Agapic Love

Arguments about religion can quickly become unkind. Many of us have been wounded in the name of religion, and those wounds heal slowly, if at all. How could we make this into a class that was—on its surface, and in its content—about theology and philosophy, while really making it about something like mutual care?

I just mentioned that great commandment: Love God with your heart, soul, mind, and strength, Jesus said, echoing Moses. Then he added a second commandment: love your neighbor as yourself. Everything else hangs on these two commandments, he said.

Explaining those two commandments would be almost as hard as trying to keep them, so I won’t try to do so here. I’ll just point out that it’s fascinating to command someone to love someone else; that the love that’s called for here is agapic love, i.e. the love that seeks the good and flourishing of the beloved; and that the commandments are so lacking in specificity as to call for both extensive commentary and continued practice. They’re vague commandments, which means they require us to work them out in community, over time. And in all likelihood we’ll never get them right. That may seem like a weakness, but it also strikes me as offering the freedom to try and to fail and to help one another to try again.

Anxiety, Ultimate Concerns, and Societal “Stress Fractures”

Which brings me to the most recent incarnation of my Theology and Philosophy in Dialogue class. Over the last few years it seems to me that my students have become more anxious about their economic futures, more stressed about exams and jobs, more focused on education and work as competition for rank. I could be wrong, but as the stress and anxiety have grown, it seems like my students are so busy jockeying for position that they have a hard time putting the cause of their stress into words. On top of all this, here in the United States, it feels like we’ve been using stronger words so that we can give voice to our anxiety more quickly. We aren’t broken, but we’ve got lots of hairline stress fractures that are too small to see. We aren’t bleeding, but we’ve got a constant dull ache.

In other words, it seems like we’re fearful without being able to identify the object of our fear, and that has us prepared to see enemies wherever we look. This does not make it easy to love our neighbors as ourselves (unless we also have that kind of distrust of ourselves, which is a real possibility, I suppose.) And at least in the way Paul Tillich described God: whatever we regard as our ultimate concern functions as our God. When economic anxiety, jostling for rank, or fear of losing one’s place in the future, (these are all ways of saying the same thing, I think) take on the role of “ultimate concern” in our lives, they become our gods.

The course I’m teaching this semester still has traces of every previous semester’s influences. We talk a little about apologetics, and that’s a helpful way of teaching students about logic, inference, probability, and certainty. (Ask some of them about “doxastic certainty” or my “haystack problem” and you’ll see what I mean.)

And we still talk about postmodernism, though as my career has shifted from the philosophy of religion to environmental philosophy, ethics, and policy, I’m inclined to follow Scott Russell Sanders’ view (see note, below) that if we spend too much time theorizing and not enough time caring for the world we share, incredulity towards metanarratives can quickly become a new metanarrative that we fail to examine sufficiently.

And we still talk about atheisms. This semester I have sketched a dozen forms of atheism once again, and we’re now working our way through them.

Friendship, and “Best Construction”

But the aim of the class, more than anything, is friendship.

I told all the students that this was the case on the first day of class.

And here, I think, is where Theology and Philosophy can have a really helpful dialogue in our time. I teach at a Lutheran university, so it’s fitting to invoke Luther. In his Small Catechism, he offers some commentary on the Ten Commandments. His commentary on the eighth commandment is helpful. The commandment reads simply, like this:

This is hard.

“A Mutual, Joint-Stock World, In All Meridians”

It’s especially hard when we feel that others are getting ahead of us, and that we are in a competition with everyone else. If the world is a zero-sum game, then everyone run, and the Devil take the hindmost. But what if Queequeg is right? When Queequeg sees a fellow sailor drowning and no one moves to save the sailor, Queequeg leaps into the water to save his fellow. There is no question of whether they are of the same tribe, the same party, the same race, the same team. Queequeg is, as far as anyone aboard the ship knows, a cannibal. And yet the narrator, observing Queequeg’s agapic care for his fellow sailor, offers this comment:

It’s much easier to approach theological conversations with the idea that our theology is a weapon and that our enemies are those with whom we disagree. It’s so easy to forget what Saint Paul wrote, that we don’t fight against flesh and blood, but against far less tangible, invisible forces that would have us view our neighbors with malice.

Could we approach theology the way Queequeg approaches the plight of his fellow sailor? Is it possible to maintain one’s cherished beliefs while recognizing that one’s object of “ultimate concern” might be something we don’t yet see with certainty and clarity? I cannot speak for others, so I’ll just offer this confession: I’m aware of a capacity in myself to care more for my theology than for the God that my theology claims to describe. In simpler terms: my own theology can become so dear to me that it becomes an idol, displacing the very God I set out to love and serve. And how to I love and serve my God? So far, the best I can offer you is this: I should love God with all I am, and I should love my neighbor as myself. Does that seem unclear to you? It does to me. Which means I need all the help I can get in clarifying my vision. Right now I see in a glass, darkly.

The philosopher Jonathan Lear suggests a principle akin to Queequeg’s, and to Luther’s: the principle of humanity. He describes it like this:

Conclusion

It’s appropriate to me that I teach this course in Lent each year. Lent is a good time for self-examination, and that includes an examination of all kinds of pieties and supposed certainties. What is it that we hold to be of ultimate concern? What do we love with all our heart, soul, mind, and strength? That might just be playing the role of a god in our lives. If so, does that God help us to love our neighbors as ourselves?

I could be wrong in all I say in this class. I enter it with “fear and trembling,” knowing that there’s so much I don’t know, and knowing that many of my students might be wiser than I am. I know they might have seen the divine far more clearly than I ever will in this life.

But oh, how I want them to live well, not to be entangled by anxious grief, not to be afraid of the future, not to be burdened by relentless suspicions and fears.

Yes, there are other subjects I could teach, and yes, there are other jobs I could do. But for me, right now, this one feels like a good way to reexamine my own ultimate concerns, and a good way to help others to do the same. May I do so without malice, with agapic love, and with the constant practice of putting the best construction on everything.

Amen. Lord, have mercy.

*****

Notes:

* Scott Russell Sanders: I'm thinking of his essay, "The Warehouse and the Wilderness," and in particular the opening pages of that essay. You can find it in A Conservationist Manifesto, beginning on page 71. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009)

* Ulpian's words are cited in Justinian, Institutes, Book 1, Title 1, Sec. 3.

* Lear has an endnote at the end of this sentence. It reads: “This principle is also known as the ‘principle of charity,’ and the most famous arguments for it are given by Donald Davidson. See his “Radical Interpretation,” in Inquiries Into Truth And Interpretation (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984), pp. 136-137; “Belief and the Basis of Meaning,” ibid., pp. 152-153; “Thought and Talk,” ibid., pp. 168-169; “On the Very Idea of a Conceptual Scheme,” ibid., pp. 196-197; “The Method of Truth in Metaphysics,” ibid., pp. 200-201.”

Apologetics and Postmodernism

When I first taught it, I made it a class about apologetics and postmodernism. By “apologetics” I mean the work of giving a reasoned account of one’s commitments; by “postmodernism,” I mean the suspicion that what look like reasoned accounts might have unexamined depths and layers to them. In the context of theism—and in particular Christian theism—apologetics has a long history that reaches back to the early years of Christianity. Saint Peter wrote in his longer letter that Christians should always be prepared to give a reasoned defense of the hope they bore within them. That phrase “reasoned defense” is a translation of the Greek word apologia, which can mean a legal defense, and from which we get our word “apologetics.”

When Saint Paul of Tarsus found himself in Athens, speaking to Stoic and Epicurean philosophers on the Areopagus, he tried to explain his beliefs not in the terms of his culture but in theirs. He doesn’t seem to have won many over to his views that day, but if nothing else was accomplished, at the end of the conversation it was clearer where Paul and the Greek philosophers were in agreement and where they disagreed. If immediate conversion was the aim of his speech, it wasn’t a great speech. But if he aimed to build a bridge of mutual understanding, I’d say he was pretty successful.

One of the keys to his success, I think, was familiarity with the culture around him. I’ve written about this elsewhere, so I won’t belabor it here, but I’ll just point out that Paul quoted two Greek philosophical poets, Epimenides and Aratos, and he did so in a culturally appropriate and significant place, since several centuries before Paul’s travels, Epimenides (who was from Crete) also traveled to Athens and also spoke on the Areopagus about the gods and salvation.

Understanding Atheism(s)

A few years after I started teaching that course, I shifted the course to take seriously the “New Atheists.” I figured that if my religious students graduated without hearing the strongest challenges to their faith, I, as a professor who teaches theology, was letting them down. I wanted them to know that soon they’d hear strong arguments against their religious heritage, beliefs, and practices, and that these arguments should be taken seriously. For my Christian students, I framed this as a way of living the commandment to love God with one’s mind.

Of course, only some of my students are religious, and some of the religious students aren’t Christians. (I’m at a Lutheran university in a small Midwestern city, so until recently most of them were at least culturally Christian; that’s changing quickly, though.) I wanted this to be a class that was helpful for everyone, so I started to turn this into a class about mutual understanding. I now teach my students how to distinguish between a dozen different kinds of (and reasons for) atheism, lest they make the mistake of oversimplifying the complexity of their neighbors and of themselves.

Understanding and Agapic Love

Arguments about religion can quickly become unkind. Many of us have been wounded in the name of religion, and those wounds heal slowly, if at all. How could we make this into a class that was—on its surface, and in its content—about theology and philosophy, while really making it about something like mutual care?

I just mentioned that great commandment: Love God with your heart, soul, mind, and strength, Jesus said, echoing Moses. Then he added a second commandment: love your neighbor as yourself. Everything else hangs on these two commandments, he said.

Explaining those two commandments would be almost as hard as trying to keep them, so I won’t try to do so here. I’ll just point out that it’s fascinating to command someone to love someone else; that the love that’s called for here is agapic love, i.e. the love that seeks the good and flourishing of the beloved; and that the commandments are so lacking in specificity as to call for both extensive commentary and continued practice. They’re vague commandments, which means they require us to work them out in community, over time. And in all likelihood we’ll never get them right. That may seem like a weakness, but it also strikes me as offering the freedom to try and to fail and to help one another to try again.

Anxiety, Ultimate Concerns, and Societal “Stress Fractures”

Which brings me to the most recent incarnation of my Theology and Philosophy in Dialogue class. Over the last few years it seems to me that my students have become more anxious about their economic futures, more stressed about exams and jobs, more focused on education and work as competition for rank. I could be wrong, but as the stress and anxiety have grown, it seems like my students are so busy jockeying for position that they have a hard time putting the cause of their stress into words. On top of all this, here in the United States, it feels like we’ve been using stronger words so that we can give voice to our anxiety more quickly. We aren’t broken, but we’ve got lots of hairline stress fractures that are too small to see. We aren’t bleeding, but we’ve got a constant dull ache.

In other words, it seems like we’re fearful without being able to identify the object of our fear, and that has us prepared to see enemies wherever we look. This does not make it easy to love our neighbors as ourselves (unless we also have that kind of distrust of ourselves, which is a real possibility, I suppose.) And at least in the way Paul Tillich described God: whatever we regard as our ultimate concern functions as our God. When economic anxiety, jostling for rank, or fear of losing one’s place in the future, (these are all ways of saying the same thing, I think) take on the role of “ultimate concern” in our lives, they become our gods.

The course I’m teaching this semester still has traces of every previous semester’s influences. We talk a little about apologetics, and that’s a helpful way of teaching students about logic, inference, probability, and certainty. (Ask some of them about “doxastic certainty” or my “haystack problem” and you’ll see what I mean.)

And we still talk about postmodernism, though as my career has shifted from the philosophy of religion to environmental philosophy, ethics, and policy, I’m inclined to follow Scott Russell Sanders’ view (see note, below) that if we spend too much time theorizing and not enough time caring for the world we share, incredulity towards metanarratives can quickly become a new metanarrative that we fail to examine sufficiently.

And we still talk about atheisms. This semester I have sketched a dozen forms of atheism once again, and we’re now working our way through them.

Friendship, and “Best Construction”

But the aim of the class, more than anything, is friendship.

I told all the students that this was the case on the first day of class.

And here, I think, is where Theology and Philosophy can have a really helpful dialogue in our time. I teach at a Lutheran university, so it’s fitting to invoke Luther. In his Small Catechism, he offers some commentary on the Ten Commandments. His commentary on the eighth commandment is helpful. The commandment reads simply, like this:

“Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor.”Like the other commandments I’ve mentioned, it is only a few words long. And like those others, it leaves room for commentary. Luther’s commentary does something that I find very helpful. While the commandment is negative (“thou shalt not,” it says) Luther thought that alongside each negative commandment was something positive. So he writes:

What does this mean?--Answer. We should fear and love God that we may not deceitfully belie, betray, slander, or defame our neighbor, but defend him, [think and] speak well of him, and put the best construction on everything.”This is akin to what Plato offers in several ways in his Republic, and to Ulpian’s legal principle of “giving to each person their due,” (see note, below) but it goes a little further, with an agapic tinge: Luther doesn’t just tell us not to lie, nor does he tell us to be simply honest, but to put the best construction on everything.

This is hard.

“A Mutual, Joint-Stock World, In All Meridians”

It’s especially hard when we feel that others are getting ahead of us, and that we are in a competition with everyone else. If the world is a zero-sum game, then everyone run, and the Devil take the hindmost. But what if Queequeg is right? When Queequeg sees a fellow sailor drowning and no one moves to save the sailor, Queequeg leaps into the water to save his fellow. There is no question of whether they are of the same tribe, the same party, the same race, the same team. Queequeg is, as far as anyone aboard the ship knows, a cannibal. And yet the narrator, observing Queequeg’s agapic care for his fellow sailor, offers this comment:

Was there ever such unconsciousness? He did not seem to think that he at all deserved a medal from the Humane and Magnanimous Societies. He only asked for water—fresh water—something to wipe the brine off; that done, he put on dry clothes, lighted his pipe, and leaning against the bulwarks, and mildly eyeing those around him, seemed to be saying to himself—“It’s a mutual, joint-stock world, in all meridians. We cannibals must help these Christians.” -- Herman Melville, Moby Dick. (New York: Signet, 1980) 76

It’s much easier to approach theological conversations with the idea that our theology is a weapon and that our enemies are those with whom we disagree. It’s so easy to forget what Saint Paul wrote, that we don’t fight against flesh and blood, but against far less tangible, invisible forces that would have us view our neighbors with malice.

Could we approach theology the way Queequeg approaches the plight of his fellow sailor? Is it possible to maintain one’s cherished beliefs while recognizing that one’s object of “ultimate concern” might be something we don’t yet see with certainty and clarity? I cannot speak for others, so I’ll just offer this confession: I’m aware of a capacity in myself to care more for my theology than for the God that my theology claims to describe. In simpler terms: my own theology can become so dear to me that it becomes an idol, displacing the very God I set out to love and serve. And how to I love and serve my God? So far, the best I can offer you is this: I should love God with all I am, and I should love my neighbor as myself. Does that seem unclear to you? It does to me. Which means I need all the help I can get in clarifying my vision. Right now I see in a glass, darkly.

The philosopher Jonathan Lear suggests a principle akin to Queequeg’s, and to Luther’s: the principle of humanity. He describes it like this:

“The interpretation thus fits what philosophers call the principle of humanity: that we should try to interpret others as saying something true—guided by our own sense of what is true and of what they could reasonably believe.” -- Jonathan Lear, Radical Hope. 4 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006) (See note below)The Episcopal Church’s Book of Common Prayer offers another commentary on the fourth commandment, the commandment not to take the name of God in vain. The Book of Common Prayer rephrases the commandment like this:

You shall not invoke with malice the Name of the Lord your God.

Amen. Lord have mercy.The rephrasing is a commentary on “in vain.” Invoking God’s name in vain is equated with invoking it with malice, that is, with the opposite of agapic love.

Conclusion

It’s appropriate to me that I teach this course in Lent each year. Lent is a good time for self-examination, and that includes an examination of all kinds of pieties and supposed certainties. What is it that we hold to be of ultimate concern? What do we love with all our heart, soul, mind, and strength? That might just be playing the role of a god in our lives. If so, does that God help us to love our neighbors as ourselves?

I could be wrong in all I say in this class. I enter it with “fear and trembling,” knowing that there’s so much I don’t know, and knowing that many of my students might be wiser than I am. I know they might have seen the divine far more clearly than I ever will in this life.

But oh, how I want them to live well, not to be entangled by anxious grief, not to be afraid of the future, not to be burdened by relentless suspicions and fears.

Yes, there are other subjects I could teach, and yes, there are other jobs I could do. But for me, right now, this one feels like a good way to reexamine my own ultimate concerns, and a good way to help others to do the same. May I do so without malice, with agapic love, and with the constant practice of putting the best construction on everything.

Amen. Lord, have mercy.

*****

Notes:

* Scott Russell Sanders: I'm thinking of his essay, "The Warehouse and the Wilderness," and in particular the opening pages of that essay. You can find it in A Conservationist Manifesto, beginning on page 71. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009)

* Ulpian's words are cited in Justinian, Institutes, Book 1, Title 1, Sec. 3.

* Lear has an endnote at the end of this sentence. It reads: “This principle is also known as the ‘principle of charity,’ and the most famous arguments for it are given by Donald Davidson. See his “Radical Interpretation,” in Inquiries Into Truth And Interpretation (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984), pp. 136-137; “Belief and the Basis of Meaning,” ibid., pp. 152-153; “Thought and Talk,” ibid., pp. 168-169; “On the Very Idea of a Conceptual Scheme,” ibid., pp. 196-197; “The Method of Truth in Metaphysics,” ibid., pp. 200-201.”

∞

How I Write - A Quick Reply To A Young Writer

This morning I came to the office to find an email from a student at another college. They were writing to ask advice for a young writer. In my own college years writing often felt like a challenge to overcome, especially when I was writing simply to satisfy a course requirement. After I graduated, I discovered that writing helped me to think and to communicate more clearly. For the last few decades, I've written more and more, and in general I find it to be a pleasant activity. I lost my ability to write for a little while after I was injured three years ago, and the process of re-learning it has been good for my mind and my spirit alike.

The email I received was polite and kind, and I thought it worth my time to write a short reply even though I had other urgent tasks to get to. I never want to let the truly important abdicate to the merely urgent; tasks that clamor are not always the best tasks, and those opportunities that speak softly are not always the least valuable. Here's the email I received, and my reply. I've edited the email I received to protect the author's privacy and to highlight their question and some of my main points in boldface. I've edited my reply slightly as well, since I've got a few minutes to do so.

If you've got good advice for my correspondent, feel free to offer your advice in the comments below. (I'll delete advertisements, though.)

Dear Friend,

Thanks for your thoughtful question. I'm not sure I've got a one-size-fits-all process, but I'm happy to share what I've learned and what I do. I've only got time for a short reply this morning, so apologies in advance for the brevity of this note. I have some students coming by in a few minutes and I like to try to be present for those who are right in front of me as much as possible. I suppose it's sort of a spiritual practice for me, that "being present." The alternative (for me, anyway) is to spend too much of my time not being present, which usually takes the form of stress and anxiety about that which is geographically or chronologically distant. Anyway, while my students aren't here, I'm regarding this email from you as your "presence" in my office, so let's talk about writing...

...which I suppose we've already begun doing. For me, one of the most helpful things has been making sure not to regard writing as an optional exercise. (It's too easy for me to let the urgent crowd out the important.) Writing matters to me because it helps me to think and it helps me to be in conversation with others. If I don't give it at least a little of my time - on a regular basis, that is - then my ability to write begins to atrophy. Disciplines that matter - the ones that are most connected to our best loves - should be treated like respiration; they need to be regular and constant. If writing is a matter of loving your neighbor for you, then write regularly, just like you breathe regularly.

Of course, the metaphor breaks down, because we breathe involuntarily and always, whereas we only write occasionally. But it's at least a partly useful metaphor. Because I want to be ready to write, I keep a paper notebook in my pocket all the time, remembering the words from one of the Narnia stories (Prince Caspian, maybe?) Hmm. Let's see. Yes, here it is:

Yes, it was Prince Caspian. And here's one of my other tricks: I write after each book I read. With each book, I take time to jot down a few words and a few lines that really mattered to me in that book. Then, when I want quick access to those words, I've got them all in a single file on my computer, and I can search for the word "ink" or "scholar" and up comes this quote. My file of quotations from books is now 130 pages long. (Don't despair - I've been adding to it for 20 years!) It's a tremendous resource for writing, and it helps me to remember what I read and where I read it.

Two more quick things, since I've got to go:

1) My graduate school faculty told me that writing a 300-page dissertation seemed like a lot, but if I thought of it as a page a day for a year, it would seem much smaller, and much easier. They were right.

2) I find it helpful to write more than one thing at a time. I'll work on one thing for a while - maybe only a few minutes a day - and then I find my mind is tired of writing and thinking about that subject. So I will turn to another task, and I often find I have new energy. Oddly, I wrote my first book while I was also writing my dissertation. I'd write the doctoral thesis during the day, and then, at night, I'd write the book as a way of distracting my mind and relaxing. Now I find that if I'm working on only one thing I feel great stress. Will I finish it? What if I mess it up? These questions haunt me. But when I have many writing projects ongoing, I don't mind it very much if I run into a wall of writer's block on one of them. True story: I have written several books that I will likely never publish, and I have half-written hundreds of articles and books that I may never publish. But each one is still on my computer, and I often return to those half-written pieces to scavenge a few footnotes or paragraphs or choice words. The unfinished tasks aren't on the scrap heap; they're unpolished gems in my store-room just waiting to be set in a new piece of jewelry. I'm not ashamed of them even though I don't wear them in public; they're treasures even though most people will never see them.

I hope this helps. Keep at it! Writing has been a great source of food for my mind and a great nourishment to my convivial conversations as well. I hope you find it to be of similar benefit.

All good things,

Dave

P.S. Here are a few other things I've written about writing, and teaching writing, and the role of nature in teaching me how to write.

The email I received was polite and kind, and I thought it worth my time to write a short reply even though I had other urgent tasks to get to. I never want to let the truly important abdicate to the merely urgent; tasks that clamor are not always the best tasks, and those opportunities that speak softly are not always the least valuable. Here's the email I received, and my reply. I've edited the email I received to protect the author's privacy and to highlight their question and some of my main points in boldface. I've edited my reply slightly as well, since I've got a few minutes to do so.

If you've got good advice for my correspondent, feel free to offer your advice in the comments below. (I'll delete advertisements, though.)

Dr. O'Hara,

I'm emailing you on a rather odd premise. I am a second-year student [in] college, and an avid follower of yours on Twitter. Over the course of about six months I have admired your work from afar. I would like to say your passion not only for your students, but your work, is nothing less than inspiring. That being said -- without taking up too much of your time -- I would like to ask for your advice. I know that you have written and contributed to many books. I have started one of my own, and would like to know how you go about the process of writing? I know it is a rather vague question, but I am just getting to about seven thousand words and fifty plus seems daunting. Do you have any advice?

Again, I am sure you are a very busy man and if this isn't something you have time to entertain I wholeheartedly understand.

Thank you for your time!

[Signature]

Dear Friend,

Thanks for your thoughtful question. I'm not sure I've got a one-size-fits-all process, but I'm happy to share what I've learned and what I do. I've only got time for a short reply this morning, so apologies in advance for the brevity of this note. I have some students coming by in a few minutes and I like to try to be present for those who are right in front of me as much as possible. I suppose it's sort of a spiritual practice for me, that "being present." The alternative (for me, anyway) is to spend too much of my time not being present, which usually takes the form of stress and anxiety about that which is geographically or chronologically distant. Anyway, while my students aren't here, I'm regarding this email from you as your "presence" in my office, so let's talk about writing...

...which I suppose we've already begun doing. For me, one of the most helpful things has been making sure not to regard writing as an optional exercise. (It's too easy for me to let the urgent crowd out the important.) Writing matters to me because it helps me to think and it helps me to be in conversation with others. If I don't give it at least a little of my time - on a regular basis, that is - then my ability to write begins to atrophy. Disciplines that matter - the ones that are most connected to our best loves - should be treated like respiration; they need to be regular and constant. If writing is a matter of loving your neighbor for you, then write regularly, just like you breathe regularly.

Of course, the metaphor breaks down, because we breathe involuntarily and always, whereas we only write occasionally. But it's at least a partly useful metaphor. Because I want to be ready to write, I keep a paper notebook in my pocket all the time, remembering the words from one of the Narnia stories (Prince Caspian, maybe?) Hmm. Let's see. Yes, here it is:

“Have you pen and ink, Master Doctor?”“A scholar is never without them, your Majesty,” answered Doctor Cornelius.

– C.S. Lewis, Prince Caspian, ch. 13

Yes, it was Prince Caspian. And here's one of my other tricks: I write after each book I read. With each book, I take time to jot down a few words and a few lines that really mattered to me in that book. Then, when I want quick access to those words, I've got them all in a single file on my computer, and I can search for the word "ink" or "scholar" and up comes this quote. My file of quotations from books is now 130 pages long. (Don't despair - I've been adding to it for 20 years!) It's a tremendous resource for writing, and it helps me to remember what I read and where I read it.

Two more quick things, since I've got to go:

1) My graduate school faculty told me that writing a 300-page dissertation seemed like a lot, but if I thought of it as a page a day for a year, it would seem much smaller, and much easier. They were right.

2) I find it helpful to write more than one thing at a time. I'll work on one thing for a while - maybe only a few minutes a day - and then I find my mind is tired of writing and thinking about that subject. So I will turn to another task, and I often find I have new energy. Oddly, I wrote my first book while I was also writing my dissertation. I'd write the doctoral thesis during the day, and then, at night, I'd write the book as a way of distracting my mind and relaxing. Now I find that if I'm working on only one thing I feel great stress. Will I finish it? What if I mess it up? These questions haunt me. But when I have many writing projects ongoing, I don't mind it very much if I run into a wall of writer's block on one of them. True story: I have written several books that I will likely never publish, and I have half-written hundreds of articles and books that I may never publish. But each one is still on my computer, and I often return to those half-written pieces to scavenge a few footnotes or paragraphs or choice words. The unfinished tasks aren't on the scrap heap; they're unpolished gems in my store-room just waiting to be set in a new piece of jewelry. I'm not ashamed of them even though I don't wear them in public; they're treasures even though most people will never see them.

I hope this helps. Keep at it! Writing has been a great source of food for my mind and a great nourishment to my convivial conversations as well. I hope you find it to be of similar benefit.

All good things,

Dave

P.S. Here are a few other things I've written about writing, and teaching writing, and the role of nature in teaching me how to write.

∞

What's In A Name? Almanzo Wilder and El Manzoor

In her novel Little Town on the Prairie, Laura Ingalls Wilder tells why her husband was named Almanzo. It's a story that she learned in De Smet, South Dakota, but it reaches back a thousand years or so, through New York, and England, to somewhere in the Middle East, where Almanzo's ancestor had his life saved by "an Arab or somebody" named El Manzoor.

It's worth remembering that act of kindness shown to a Crusader, by a man with a Persian name. The Wilder family remembered that act centuries later. ("Manzoor" and variants of it are fairly common in Iran today. For example, the kind and brilliant former Director of the Toronto and San Francisco Operas, Lotfi Mansouri, was born in Iran and educated in California.)

This story makes me wonder: how might I live my life in such a way that another family will be glad to remember me a thousand years from now?

You can read the full text of my short essay about Almanzo and El Manzoor in today's Sioux Falls Argus Leader.

Since the essay in the Argus doesn't include my footnotes, here are the relevant citations:

It's worth remembering that act of kindness shown to a Crusader, by a man with a Persian name. The Wilder family remembered that act centuries later. ("Manzoor" and variants of it are fairly common in Iran today. For example, the kind and brilliant former Director of the Toronto and San Francisco Operas, Lotfi Mansouri, was born in Iran and educated in California.)

This story makes me wonder: how might I live my life in such a way that another family will be glad to remember me a thousand years from now?

You can read the full text of my short essay about Almanzo and El Manzoor in today's Sioux Falls Argus Leader.

Since the essay in the Argus doesn't include my footnotes, here are the relevant citations:

∞

Of Men and of Angels

"If I speak with the tongues of men and of angels, but I have not love, then I have become a resounding gong or a clanging cymbal."

That's from one of St. Paul's letters to the church in Corinth. It's a passage often read at weddings, probably because it speaks eloquently about agapic love.

I like it for another reason: it has a nice onomatopoeic pun in the Greek text. Paul's "If I speak..." is lalo; his "clanging" is alaladzon, which sounds like the noise a gong makes and sounds like it could mean "un-speaking." (In Greek, words that begin with "a-" are often like English words beginning with "un-".)

This week, as we approach the third Sunday in Advent, I was looking again at a poem I wrote during this week a few years ago, after the school shooting in Newtown. In it I compared first responders and teachers and others who give up so much for the sake of the common good to angels. That is my second-most read post ever.

The most-read post is one I wrote after Ferguson, about the militarization of our first responders, and the way the tools we equip ourselves with change the way we interact with the world - and with other people.

Both of these posts are about public servants. Taken together they remind me that what is done in love can be heroic and life-giving, and what is done in fear can become tyrannical. They remind me that we have a tendency to revere the outward signs of badges and uniforms, when we should judge characters by the habits they embody and by the actions that show the habits.

And they remind me that we have a long, long way to go before we can say we have learned to love one another.

*****

I should add that even the title to this post is misleading. The word Paul uses is not "men" but "humans." I like the cadence of the old translation "men" but the word is anthropon, not andron. Normally I prefer the more inclusive (and more accurate) "humans" but I first learned this verse in an older, poetic translation and the rhythm of it has stuck with me.

That's from one of St. Paul's letters to the church in Corinth. It's a passage often read at weddings, probably because it speaks eloquently about agapic love.

I like it for another reason: it has a nice onomatopoeic pun in the Greek text. Paul's "If I speak..." is lalo; his "clanging" is alaladzon, which sounds like the noise a gong makes and sounds like it could mean "un-speaking." (In Greek, words that begin with "a-" are often like English words beginning with "un-".)

This week, as we approach the third Sunday in Advent, I was looking again at a poem I wrote during this week a few years ago, after the school shooting in Newtown. In it I compared first responders and teachers and others who give up so much for the sake of the common good to angels. That is my second-most read post ever.

The most-read post is one I wrote after Ferguson, about the militarization of our first responders, and the way the tools we equip ourselves with change the way we interact with the world - and with other people.

Both of these posts are about public servants. Taken together they remind me that what is done in love can be heroic and life-giving, and what is done in fear can become tyrannical. They remind me that we have a tendency to revere the outward signs of badges and uniforms, when we should judge characters by the habits they embody and by the actions that show the habits.

And they remind me that we have a long, long way to go before we can say we have learned to love one another.

*****

I should add that even the title to this post is misleading. The word Paul uses is not "men" but "humans." I like the cadence of the old translation "men" but the word is anthropon, not andron. Normally I prefer the more inclusive (and more accurate) "humans" but I first learned this verse in an older, poetic translation and the rhythm of it has stuck with me.

∞

Protecting Borders, Loving Neighbors, And The Economics Of Child Migration

Time Magazine reported last week that President Obama is seeking 2 billion dollars to reduce the flow of young illegal immigrants across the U.S.-Mexico border.

Too often our approach to this problem is, like many U.S. political questions, polarized into mutually repellent views about how we should view our laws. Should we reform them or enforce them? Let me suggest another angle from which to consider the problem.

Eight years ago, Reynold Nesiba (an economist who is my friend and colleague) and I co-taught a course for American students in Nicaragua. The purpose of the course was to spend time thinking and talking about the effects of globalization on a small developing nation.

We both prefer to teach contextually, so that the assertions of our readings and lectures can be supported and challenged by what the students see and experience in the places we visit.

We spent time with collective coffee growers, and with big coffee processors; with small, independent textile workers and in an international textile plant built in a tax-free zone in Managua. We did homestays and met with development workers, a health clinic and a local church. We met with and listened to as many people, from as many points of view, as we could.

The downside to teaching this way is that both students and professors become much more aware of the complexity of the problems of globalization, and facile, armchair solutions to those problems tend to fall quickly to pieces. That is to say, the downside to teaching this way is that it makes it harder to maintain simplistic and dogmatic views. Which is to say, it's a good way to educate people.

Although the course made many things unclear, it made a few things clearer. Among them are these:

If I'm right, though, then it gives some context to the persistent problem of illegal migration across our southern border, and it suggests a remedy.

The problem is plain: poor people are following the money trail, and fleeing the harsh economic conditions that prevail in poor countries.

The remedy is also plain, even if it is not easy: we need to figure out a way to increase the flow of capital into places like Nicaragua, and to do it in such a way that it increases jobs (not merely increasing the income of the top earners) and increases the tax base. One such possibility - especially if my second bullet point, above, is correct - would be to examine the way farm subsidies might actually be decreasing our ability to secure our borders. Our nation reaps profit from Nicaragua. Is it possible to do so in a way that also benefits Nicaragua?

I don't mean to pretend to be an expert here. I do have some relevant experience in Central America (from teaching regularly in Nicaragua, Guatemala, and Belize) but it's far from being hard data. But surely what we need is not fewer anecdotes but more stories from and about people who are most affected by the economies of our several American nations. If we are to love our neighbors, we need to learn who they are and what drives them. A mother who would send her young child, alone, across Mexico in search of a new life is either wicked or desperate, and the latter seems the likelier story. the roots of the word "desperate" mean "without hope." Loving our neighbors surely must include trying to give hope to the hopeless, and not merely building a wall across the only path towards hope that they can imagine.

Too often our approach to this problem is, like many U.S. political questions, polarized into mutually repellent views about how we should view our laws. Should we reform them or enforce them? Let me suggest another angle from which to consider the problem.

Eight years ago, Reynold Nesiba (an economist who is my friend and colleague) and I co-taught a course for American students in Nicaragua. The purpose of the course was to spend time thinking and talking about the effects of globalization on a small developing nation.

We both prefer to teach contextually, so that the assertions of our readings and lectures can be supported and challenged by what the students see and experience in the places we visit.

|

| Coffee beans grown in Nicaragua. |

We spent time with collective coffee growers, and with big coffee processors; with small, independent textile workers and in an international textile plant built in a tax-free zone in Managua. We did homestays and met with development workers, a health clinic and a local church. We met with and listened to as many people, from as many points of view, as we could.

|

| Workers sort coffee beans. |

Although the course made many things unclear, it made a few things clearer. Among them are these:

If I'm right, though, then it gives some context to the persistent problem of illegal migration across our southern border, and it suggests a remedy.

The problem is plain: poor people are following the money trail, and fleeing the harsh economic conditions that prevail in poor countries.

The remedy is also plain, even if it is not easy: we need to figure out a way to increase the flow of capital into places like Nicaragua, and to do it in such a way that it increases jobs (not merely increasing the income of the top earners) and increases the tax base. One such possibility - especially if my second bullet point, above, is correct - would be to examine the way farm subsidies might actually be decreasing our ability to secure our borders. Our nation reaps profit from Nicaragua. Is it possible to do so in a way that also benefits Nicaragua?

I don't mean to pretend to be an expert here. I do have some relevant experience in Central America (from teaching regularly in Nicaragua, Guatemala, and Belize) but it's far from being hard data. But surely what we need is not fewer anecdotes but more stories from and about people who are most affected by the economies of our several American nations. If we are to love our neighbors, we need to learn who they are and what drives them. A mother who would send her young child, alone, across Mexico in search of a new life is either wicked or desperate, and the latter seems the likelier story. the roots of the word "desperate" mean "without hope." Loving our neighbors surely must include trying to give hope to the hopeless, and not merely building a wall across the only path towards hope that they can imagine.

*****

| |

| The old cathedral of Managua. Unused since it was damaged by an earthquake 40 years ago. |

Here are a couple more photos from our course. I've only included photos from cooperatives because the international firms we visited prohibited photography, claiming they were protecting "trade secrets." As near as I could tell, there wasn't much to protect in those places, since the machinery was all very simple: sewing machines, bean sorting machines and baggers. More likely, they were concerned about bad publicity arising from documentation of their working conditions. The photo of the cathedral in Managua is a reminder of how poor the capital city is: such a beautiful building has languished for four decades because there are no funds to restore it.

|

| A coffee cooperative in the mountains of Nicaragua. |

|

|||

| A sewing cooperative. |

∞

Theodicy and Phenomenal Curiosity

I have, right now, a terrific headache. It is a long, spidery headache whose bulging, raspy abdomen sits over my eyes and whose long forelegs reach across my head and down my spine. One leg is probing my belly and provoking nausea. It came on suddenly, dropping from the air, and it has become a constant efflorescence of discomfort. Each moment it is renewed. I try to turn my attention away, and it pulses, drawing me back. Fine, I will give it my attention and stare it down, dominate it. No, it has no steady gaze to match; every instant it is a new hostility towards being. It will not hold still, it is my Proteus, but I am no Menelaus. I cannot grapple it into submission.

I should stop writing, stop looking at the screen, but I want, as Bugbee says in the first page of The Inward Morning, to "get it down," to attend to this moment as its own revelation. I want, in a way, to put this idea to the test. I can write and think when I am feeling well, but it is hard to write in times like this.

Life is interesting. This, too, is an interesting moment, and this pain is interesting.

The urge to turn this into a rule for others is to be resisted. My pain is interesting to me because I have chosen to make it so. I have chosen to be curious while I am able. And this is not the worst headache I've had, it's just strong and annoying.

But -- and this is the important thing, I think -- I must not insist that others do the same. I must not say that "pain is God's megaphone to rouse a deaf world," I must not say that "all things work together for good," that pain is all part of a bigger plan.

I admit that all of that may be true. It may be that the suffering of others will be the darkness that makes the brightness of the divine and eternal chiaroscuro shine brighter.

But to insist that pain is good is the privilege of those who are in no pain and the blasphemy of those who have forgotten fellow-feeling. It is lacking in sympathy, and in kindness. It is, in short, lacking in love.

In one of his letters to the church in Corinth, St. Paul wrote something like this: no matter what I say, no matter how beautifully I say it, if I speak without love, I might as well not be speaking at all. (I am paraphrasing, so if you're someone who's bothered by people paraphrasing the Bible and want to see his words, here you go.)

I cannot write any more right now.

*****

It is now several days later, and the pain is gone. Which means that now, when I think of the pain, I do so through the watery filter of time, which bends and distorts the image like water bending the image of the dipped oar. I no longer behold it as I did when I was in medias res, in the midst of things. I'm glad it doesn't hurt, but I've got to remember not to make it seem easier than it was.

Years ago a surgeon cut me open "from stem to stern" (his cheerful words, not mine) and then stapled me back together. I awoke barely able to breathe. The painkillers they gave me didn't remove the pain, they only relocated it to a part of my brain that cared less, made it less the center of my attention. Even there, it constantly tried to crawl back into the center, to take over my consciousness. I'm grateful that it did not last long. My awareness of that gratitude gives me great sympathy for those who cannot make their pain end, who have no hope that soon the healing will make the pain a dull memory rather than a sharp presence goading their consciousness.

At the time, I found it a helpful strategy to attend to the pain as a curiosity, to tell myself "this is interesting," and to ask "what can I learn from this pain right now?" I couldn't sustain this for long, but I could do it again and again, with ever-renewed curiosity, and I found enormous solace and spiritual interest in it. It put me above my pain, and stripped my pain of its domineering attitude. It no longer loomed over me while I gazed down at it with wondering eyes.

But again, this is extremely difficult to sustain, and it probably takes a certain weird, philosophical warp of mind to begin with, a phenomenal curiosity cultivated and strengthened by long habit well before the pain began. It's hard to come up with something like this in the moment agony strikes.

*****

The upshot of all this, for me, is twofold: first, it is good to have discovered, in the midst of my own pain, that I may always regard my own life as interesting, no matter what happens. Second, I must always remember that this is a curious discovery I have made about myself, not a universal fact for all people.

Of course, I am writing my discovery down here because I hope that it will prove true for others. And I think its greatest application is not for the destruction of sharp physical pain but for addressing the flat white pain of boredom. When boredom drops down from above and wraps us in its gauzy, nauseating silk, this, too, can become the object of our curiosity. The very fact of our boredom may be examined, and examined profitably.

But in all our examinations, we must not be - we must never be - unkind by despising the pain of others, dismissing it and insisting that if we can dismiss it, they can too.

I should stop writing, stop looking at the screen, but I want, as Bugbee says in the first page of The Inward Morning, to "get it down," to attend to this moment as its own revelation. I want, in a way, to put this idea to the test. I can write and think when I am feeling well, but it is hard to write in times like this.

Life is interesting. This, too, is an interesting moment, and this pain is interesting.

The urge to turn this into a rule for others is to be resisted. My pain is interesting to me because I have chosen to make it so. I have chosen to be curious while I am able. And this is not the worst headache I've had, it's just strong and annoying.

But -- and this is the important thing, I think -- I must not insist that others do the same. I must not say that "pain is God's megaphone to rouse a deaf world," I must not say that "all things work together for good," that pain is all part of a bigger plan.

I admit that all of that may be true. It may be that the suffering of others will be the darkness that makes the brightness of the divine and eternal chiaroscuro shine brighter.

But to insist that pain is good is the privilege of those who are in no pain and the blasphemy of those who have forgotten fellow-feeling. It is lacking in sympathy, and in kindness. It is, in short, lacking in love.

In one of his letters to the church in Corinth, St. Paul wrote something like this: no matter what I say, no matter how beautifully I say it, if I speak without love, I might as well not be speaking at all. (I am paraphrasing, so if you're someone who's bothered by people paraphrasing the Bible and want to see his words, here you go.)

I cannot write any more right now.

*****

It is now several days later, and the pain is gone. Which means that now, when I think of the pain, I do so through the watery filter of time, which bends and distorts the image like water bending the image of the dipped oar. I no longer behold it as I did when I was in medias res, in the midst of things. I'm glad it doesn't hurt, but I've got to remember not to make it seem easier than it was.

Years ago a surgeon cut me open "from stem to stern" (his cheerful words, not mine) and then stapled me back together. I awoke barely able to breathe. The painkillers they gave me didn't remove the pain, they only relocated it to a part of my brain that cared less, made it less the center of my attention. Even there, it constantly tried to crawl back into the center, to take over my consciousness. I'm grateful that it did not last long. My awareness of that gratitude gives me great sympathy for those who cannot make their pain end, who have no hope that soon the healing will make the pain a dull memory rather than a sharp presence goading their consciousness.

At the time, I found it a helpful strategy to attend to the pain as a curiosity, to tell myself "this is interesting," and to ask "what can I learn from this pain right now?" I couldn't sustain this for long, but I could do it again and again, with ever-renewed curiosity, and I found enormous solace and spiritual interest in it. It put me above my pain, and stripped my pain of its domineering attitude. It no longer loomed over me while I gazed down at it with wondering eyes.

But again, this is extremely difficult to sustain, and it probably takes a certain weird, philosophical warp of mind to begin with, a phenomenal curiosity cultivated and strengthened by long habit well before the pain began. It's hard to come up with something like this in the moment agony strikes.

*****

The upshot of all this, for me, is twofold: first, it is good to have discovered, in the midst of my own pain, that I may always regard my own life as interesting, no matter what happens. Second, I must always remember that this is a curious discovery I have made about myself, not a universal fact for all people.

Of course, I am writing my discovery down here because I hope that it will prove true for others. And I think its greatest application is not for the destruction of sharp physical pain but for addressing the flat white pain of boredom. When boredom drops down from above and wraps us in its gauzy, nauseating silk, this, too, can become the object of our curiosity. The very fact of our boredom may be examined, and examined profitably.

But in all our examinations, we must not be - we must never be - unkind by despising the pain of others, dismissing it and insisting that if we can dismiss it, they can too.

∞

What Jesus Didn't Say

My latest contribution to Sojourners' "God's Politics" blog.

Some reflections on the surprising encounter between Jesus and the Samaritan woman he meets at the well in the fourth chapter of John's Gospel. Here's a little taste of the post:

Some reflections on the surprising encounter between Jesus and the Samaritan woman he meets at the well in the fourth chapter of John's Gospel. Here's a little taste of the post:

"We can get a lot of attention in the media by self-righteous grandstanding, but wouldn’t it be better to follow the example Jesus sets here? Rather than telling people caught in desperate sin how far their sin has removed them from God, why not invite them to come to worship?"

∞

Pornography and Prayer

A recent Wall Street Journal article talks about the way online pornography quickly develops new neural pathways that are difficult to undo. As the author puts it,

To put it differently, everyone worships something, and what we worship changes us. This is one of the good reasons to engage in prayer and worship that are intentional. (On a related note, it's a good reason to forgive, too: forgiveness keeps us from internalizing the pain others have caused us, where it can fester and devour us from within.)

(If you read my writing with any regularity you will recognize these as themes I frequently return to. If you're interested, I've written more here and here.)

One of the problems of philosophy of religion has been to try to identify that which certainly deserves our worship. This quest for certainty has often (in my view) distracted us from the more important work of liturgy, wherein we acknowledge our limitations, including our uncertainty. A good liturgy involves worshiping what we believe to be worth worshiping, while acknowledging our own limitations. After all, if worship doesn't include humility on the part of the worshiper, it is probably self-worship.

Another way of putting this is in terms of love. Charles Peirce wrote about this more than a century ago. There are many forms of worship, many kinds of prayer. Without intending to demean the prayer and worship of others, Peirce nevertheless offers what seems to him to be worth our attention: agape love, the love that seeks to nurture others:

I am not trying to moralize about pornography. In fact, I see some good in pornography, just as I recognize goodness in the aromas coming from a kitchen where good cooking happens. Pornography probably speaks to some of our most basic desires and needs, for intimacy, affection, attention, and love, as well as our simple, animal longings.

Still, like aromas from a fine kitchen, porn stimulates us without nourishing us. And by giving it too much attention we may be training ourselves to scorn good nutrition. The WSJ article suggests giving up the stimulation as a means of getting over it. I think this is incomplete without a redirection of the attention to what does in fact nourish us. Prayer and worship that refocus our conscious minds on what really merits our attention can prepare us to receive - and to give - good nutrition. That is, by shifting some of our attention from cherishing need-love to cherishing gift-love - from the love that uses others to the love that seeks their flourishing - we might make ourselves into the kind of great lovers our world most needs.

"Repetitive viewing of pornography resets neural pathways, creating the need for a type and level of stimulation not satiable in real life. The user is thrilled, then doomed."Thankfully, "doomed" may be an overstatement. As William James and so many others remind us, our habits make us who we are, so we may be able to form new habits to supplant or redirect old ones. I'm no psychologist, but it seems obvious to me that what we hold in front of our consciousness will synechistically affect everything else we think about and do. So it is no surprise that the author of this WSJ article reports that viewing porn may lead to viewing women as things rather than as people.

To put it differently, everyone worships something, and what we worship changes us. This is one of the good reasons to engage in prayer and worship that are intentional. (On a related note, it's a good reason to forgive, too: forgiveness keeps us from internalizing the pain others have caused us, where it can fester and devour us from within.)

(If you read my writing with any regularity you will recognize these as themes I frequently return to. If you're interested, I've written more here and here.)

One of the problems of philosophy of religion has been to try to identify that which certainly deserves our worship. This quest for certainty has often (in my view) distracted us from the more important work of liturgy, wherein we acknowledge our limitations, including our uncertainty. A good liturgy involves worshiping what we believe to be worth worshiping, while acknowledging our own limitations. After all, if worship doesn't include humility on the part of the worshiper, it is probably self-worship.

Another way of putting this is in terms of love. Charles Peirce wrote about this more than a century ago. There are many forms of worship, many kinds of prayer. Without intending to demean the prayer and worship of others, Peirce nevertheless offers what seems to him to be worth our attention: agape love, the love that seeks to nurture others:

"Man's highest developments are social; and religion, though it begins in a seminal individual inspiration, only comes to full flower in a great church coextensive with a civilization. This is true of every religion, but supereminently so of the religion of love. Its ideal is that the whole world shall be united in the bond of a common love of God accomplished by each man's loving his neighbour. Without a church, the religion of love can have but a rudimentary existence; and a narrow, little exclusive church is almost worse than none. A great catholic church is wanted." (Peirce, Collected Papers, 6.442-443)Notice that Peirce uses a small "c" in "catholic." He wasn't trying to proselytize for one sect; quite the opposite. He was trying to proclaim the importance of a church - that is, of a community that shares a commitment to communal worship - of nurturing love.

I am not trying to moralize about pornography. In fact, I see some good in pornography, just as I recognize goodness in the aromas coming from a kitchen where good cooking happens. Pornography probably speaks to some of our most basic desires and needs, for intimacy, affection, attention, and love, as well as our simple, animal longings.

Still, like aromas from a fine kitchen, porn stimulates us without nourishing us. And by giving it too much attention we may be training ourselves to scorn good nutrition. The WSJ article suggests giving up the stimulation as a means of getting over it. I think this is incomplete without a redirection of the attention to what does in fact nourish us. Prayer and worship that refocus our conscious minds on what really merits our attention can prepare us to receive - and to give - good nutrition. That is, by shifting some of our attention from cherishing need-love to cherishing gift-love - from the love that uses others to the love that seeks their flourishing - we might make ourselves into the kind of great lovers our world most needs.

∞

Bicycles, Handguns, and Cameras

Get Off My Hood!

I just read a post on Facebook about a bicyclist in my town who was struck by someone driving a pickup truck. The driver then yelled at the bicyclist to "get the f*** off my hood" and told him to ride on the sidewalk. The driver is obviously misinformed about our laws, as well as about civility.

The bicyclist managed to take a picture of the driver's face and his truck, but not his license plate, which is too bad.

Packing Heat On Two Wheels

The comments under the photo were especially interesting. I'm not sure if he was joking, but the bicyclist (whom I do not know) said that he often bikes with a .45 in his waistband, which dissuades drivers from treating him with hostility. This time he only had his camera, and he wasn't able to shoot pictures fast enough to capture all the evidence the police would need.

I understand his frustration. Last summer, while biking on an empty street five lanes wide, a motorist sped up behind me, swerved into my lane (I was biking along the shoulder) and yelled at me to "Get on the sidewalk!" then sped off. By the time I had my phone out, he was too far away to get a picture of his license plate. He sped off uphill, making it impossible for me to chase him down.

His recklessness and utter selfishness could have maimed or even killed me had I not safely dodged his oncoming car. His cowardice and lack of regard for my life made me livid.

You Better Outrun My Bullet

But I do not see how a gun would have helped me. Yes, perhaps he would have seen a gun in my waistband, but at his speed he very well might not have seen it. And what would I do with it? I'm not going to start squeezing off rounds at a fleeing motorist; to do so would make me a worse criminal than he. Besides, I was in no state to be handling a weapon: my heart was pounding, adrenaline was shooting through my veins. I was angry, and I was feeling that fright that comes when sudden and severe peril suddenly interrupts a calm day.

I don't want my world to be under constant surveillance, but I'm considering getting a GoPro or some other video camera that would run constantly when I bike on the street. I think if more of us did that, it would be a more effective deterrent than a firearm.

We're In This Together

More importantly, carrying a camera rather than a gun says something about community. The gun is about taking personal charge of one's security, and while I applaud the individual responsibility that implies, the camera insists that reckless driving is not my problem but our problem, a problem that we will deal with as a community, through the structures of law that constitute our community. If you harass bicyclists, I will film it, and I will hand the evidence over to the police.

This is what it means to live in a society that respects the rule of law. We don't live in the time of Euthyphro, who needed to enforce the law himself. We live in the age of the District Attorney; and whatever you may say about an individual D.A., the point of a state-appointed prosecutor is just this: she is the embodiment of our belief that to offend against one of us is to offend against all of us. We are in this together.

I don't want to foster hostility between motorists and cyclists; I want to foster mutual respect. The roads are wide enough to share. If we can learn to do so, we'll all wind up reaching good destinations, together.

*****

Update: Here's a link to an article by Jill Callison about the confrontation between the cyclist and the motorist in the Sioux Falls Argus Leader.

*****

Further Update: Here's a link to a bit of good news: the driver has been charged with several misdemeanors. This is good news for bicyclists, and bad news for hotheaded drivers unwilling to share the road with their neighbors.

I just read a post on Facebook about a bicyclist in my town who was struck by someone driving a pickup truck. The driver then yelled at the bicyclist to "get the f*** off my hood" and told him to ride on the sidewalk. The driver is obviously misinformed about our laws, as well as about civility.

The bicyclist managed to take a picture of the driver's face and his truck, but not his license plate, which is too bad.

|

| My speedy steed. Please do not hit me. |

Packing Heat On Two Wheels

The comments under the photo were especially interesting. I'm not sure if he was joking, but the bicyclist (whom I do not know) said that he often bikes with a .45 in his waistband, which dissuades drivers from treating him with hostility. This time he only had his camera, and he wasn't able to shoot pictures fast enough to capture all the evidence the police would need.