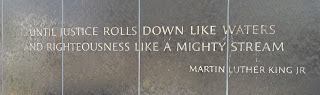

Martin Luther King

∞

Secular Liturgy

Last night I attended the Maundy Thursday service at our church. I admit I'm not a fan of sitting still, of pews in general, or of listening to sermons. I also haven't got any great love for singing with a small congregation that doesn't really like to sing.

But I've found I need liturgy in my life. Liturgies help me mark seasons. More than that, liturgies create seasons. That's what I really need, because the creation of seasons becomes, for me, a discipline of memory.

Liturgies help me to count my days, which in turn helps me to make my days count.

I used to chafe at the remembrance of birthdays. Why should one day count more than any other? And why should one day seem more a holiday than another?

I'm slowly getting it. There is nothing special about the day; what is special is the use of the day. Cheerless debunkers never tire of pointing out to me that western Christmas is celebrated on a Roman holiday, that Easter is *really* some kind of fertility rite because it's celebrated in the springtime, that all my holidays don't mean what I think they mean because someone once celebrated them in another way. As though the genealogy of the holiday should be its only meaning, as though the celebrations of the past should have magical power over me, as though I had no power to make the days mean something new to me.

And it is true: holidays and liturgies do have power. As I have said before, what we cherish in our hearts we worship, and what we worship we come to resemble or imitate. Holidays are always about remembering, and remembering is cherishing. Of course, we don't all cherish the same things. Memorial Day is, for some, a remembrance of valor and sacrifice. For others, it is a good day for a picnic with family. Both are forms of cherishing, though the thing cherished is quite different.

Much of the difference probably comes from mindfulness and intention, or lack of intention. Everyone cherishes something, but not all of us think about what we cherish. Liturgies help me to cherish mindfully.

Which is why every April 4th I read or listen to Dr. King's "I Have A Dream" speech, and weep at his loss. And why every July 4th I read the Declaration of Independence. I have set aside days in my year, every year, to read texts like these, texts that have shaped my community. Because these texts aren't done with their shaping. Texts don't hit us once and do all their work; texts seep into us, their words become our words.

Reading and re-reading and reading aloud in communities - these things are like the pouring of water through leaves or grounds - the reading percolates through the words and picks up the essential oils, the savor, the color and taste of the text, and delivers it to us like tea or hot coffee. We taste the words and then the words enter our guts, our veins, our souls.

I recently read an interview with a woman who said "I don't need to go to church to believe those things," referring to her church's beliefs. True. Just as I don't need to go to the gym to get exercise, or to believe that exercise is good for me. But if I don't make a habit of getting exercise, I find I tend not to get what my body needs. The urgent matters in life so easily overwhelm the important ones. Often, when I return from the gym, my wife asks me "How was the gym?" I always think, "It was hard. Everything I do at the gym is difficult." But it is worth doing, because it helps me to maintain my health, and to fight my own decline, to fight the slow slipping away of what I want to hold onto as long as I can. If I do this for my body, why should I not also do it for my heart and mind?

I'm not writing this to endorse all liturgies. I'm confident that there are liturgies that celebrate awful things, and that there are participants in liturgies who make poor use of the liturgies they sit through. As with most of what I write here, I'm trying to sort out what I believe, and why -- as another kind of discipline, one of remembering, and of being mindful of what I believe.

The liturgy of Maundy Thursday is not an easy one, because it reminds me of two things I am capable of: I am capable, like Jesus, of washing others' feet, and of living a life of love; and I am capable, like Jesus' friends, of betraying those people and ideals I most claim to cherish and worship. If my worship is only worship in words, I find it easy to forget to worship what is best with my body, with my life. Liturgies - and we all have liturgies - are the ways I remind my whole person to stop and remember what my words claim so easily to believe.

But I've found I need liturgy in my life. Liturgies help me mark seasons. More than that, liturgies create seasons. That's what I really need, because the creation of seasons becomes, for me, a discipline of memory.

Liturgies help me to count my days, which in turn helps me to make my days count.

I used to chafe at the remembrance of birthdays. Why should one day count more than any other? And why should one day seem more a holiday than another?

I'm slowly getting it. There is nothing special about the day; what is special is the use of the day. Cheerless debunkers never tire of pointing out to me that western Christmas is celebrated on a Roman holiday, that Easter is *really* some kind of fertility rite because it's celebrated in the springtime, that all my holidays don't mean what I think they mean because someone once celebrated them in another way. As though the genealogy of the holiday should be its only meaning, as though the celebrations of the past should have magical power over me, as though I had no power to make the days mean something new to me.

And it is true: holidays and liturgies do have power. As I have said before, what we cherish in our hearts we worship, and what we worship we come to resemble or imitate. Holidays are always about remembering, and remembering is cherishing. Of course, we don't all cherish the same things. Memorial Day is, for some, a remembrance of valor and sacrifice. For others, it is a good day for a picnic with family. Both are forms of cherishing, though the thing cherished is quite different.

Much of the difference probably comes from mindfulness and intention, or lack of intention. Everyone cherishes something, but not all of us think about what we cherish. Liturgies help me to cherish mindfully.

Which is why every April 4th I read or listen to Dr. King's "I Have A Dream" speech, and weep at his loss. And why every July 4th I read the Declaration of Independence. I have set aside days in my year, every year, to read texts like these, texts that have shaped my community. Because these texts aren't done with their shaping. Texts don't hit us once and do all their work; texts seep into us, their words become our words.

Reading and re-reading and reading aloud in communities - these things are like the pouring of water through leaves or grounds - the reading percolates through the words and picks up the essential oils, the savor, the color and taste of the text, and delivers it to us like tea or hot coffee. We taste the words and then the words enter our guts, our veins, our souls.

I recently read an interview with a woman who said "I don't need to go to church to believe those things," referring to her church's beliefs. True. Just as I don't need to go to the gym to get exercise, or to believe that exercise is good for me. But if I don't make a habit of getting exercise, I find I tend not to get what my body needs. The urgent matters in life so easily overwhelm the important ones. Often, when I return from the gym, my wife asks me "How was the gym?" I always think, "It was hard. Everything I do at the gym is difficult." But it is worth doing, because it helps me to maintain my health, and to fight my own decline, to fight the slow slipping away of what I want to hold onto as long as I can. If I do this for my body, why should I not also do it for my heart and mind?

|

| The words percolate through us, and enter our veins. |

I'm not writing this to endorse all liturgies. I'm confident that there are liturgies that celebrate awful things, and that there are participants in liturgies who make poor use of the liturgies they sit through. As with most of what I write here, I'm trying to sort out what I believe, and why -- as another kind of discipline, one of remembering, and of being mindful of what I believe.

The liturgy of Maundy Thursday is not an easy one, because it reminds me of two things I am capable of: I am capable, like Jesus, of washing others' feet, and of living a life of love; and I am capable, like Jesus' friends, of betraying those people and ideals I most claim to cherish and worship. If my worship is only worship in words, I find it easy to forget to worship what is best with my body, with my life. Liturgies - and we all have liturgies - are the ways I remind my whole person to stop and remember what my words claim so easily to believe.

∞

Love One Another: Prisons and Devotion to Enemies

In his first book, Stride Toward Freedom, Dr. King wrote "We adopt the means of nonviolence because our end is a community at peace with itself." Paraphrasing Gandhi, he added a word for those who considered themselves his enemies, "In winning our freedom we will so appeal to your heart and conscience that we will win you in the process."

This is a radical idea, one that is like the ideas of Jesus and St Paul that we should love our enemies. If your mind does not stumble over those words, you might be a saint; or you might not be listening to them.

King's argument is that we need our enemies. They need us to make them into the kind of people who embody love, not hatred. And we need - in the depths of our souls - the work of loving them in such a way that we win them over to the side of love and away from the crippling hatred that owns them.

It is easy to say "that's fine for church," or "I will love my enemy in my heart but in my life I will punish him." But what would happen if we thought of our worst enemies - I have in mind criminals and terrorists, the people we most seem to fear - as people with a "heart and conscience" that could be won. As people without whom we are incomplete.

We're good at finding ways to make people pay for their wrongdoing. We have great technology for warfare, and a brilliant system of criminal investigation and prosecution, perhaps the best history has ever seen. I don't propose eliminating those things. Instead, I am asking this: what if we decided that we would put the same creative energy and financial resources that have gone into creating our fine military, police, and courts into winning the consciences of our enemies?

When it comes to our anti-terror policies, I don't see what we can do to win terrorists' consciences, other than living our lives in such a way that anyone who supports our would-be enemies must feel shame at hating such virtuous people. That sounds to me like an end worth pursuing for its own sake, after all.

As for our prisons, our prisons seem to be good at exposing non-criminals to criminals; and to exposing criminals to more criminals, breeding gang culture. Violent criminals surely merit our censure, extraction from society, and punishment. But that doesn't mean our hearts need to be full of a desire for vengeance.

I'm not good at this, but I'm trying to become the kind of person who regards criminals as people I need, who need me to love them, who need me to win their consciences.

I believe a society needs to be prepared to use force against those who would forcefully harm others. But increasingly I am coming to believe that individuals in each society also need to be prepared to fight fire not with fire but with the healing waters of love, waters that overflow from hearts that daily struggle to regard the people we most hate and fear as the people we also most need to love. It's not easy. But it may be the only way to become "a community at peace with itself."

This is a radical idea, one that is like the ideas of Jesus and St Paul that we should love our enemies. If your mind does not stumble over those words, you might be a saint; or you might not be listening to them.

King's argument is that we need our enemies. They need us to make them into the kind of people who embody love, not hatred. And we need - in the depths of our souls - the work of loving them in such a way that we win them over to the side of love and away from the crippling hatred that owns them.

It is easy to say "that's fine for church," or "I will love my enemy in my heart but in my life I will punish him." But what would happen if we thought of our worst enemies - I have in mind criminals and terrorists, the people we most seem to fear - as people with a "heart and conscience" that could be won. As people without whom we are incomplete.

We're good at finding ways to make people pay for their wrongdoing. We have great technology for warfare, and a brilliant system of criminal investigation and prosecution, perhaps the best history has ever seen. I don't propose eliminating those things. Instead, I am asking this: what if we decided that we would put the same creative energy and financial resources that have gone into creating our fine military, police, and courts into winning the consciences of our enemies?

When it comes to our anti-terror policies, I don't see what we can do to win terrorists' consciences, other than living our lives in such a way that anyone who supports our would-be enemies must feel shame at hating such virtuous people. That sounds to me like an end worth pursuing for its own sake, after all.

As for our prisons, our prisons seem to be good at exposing non-criminals to criminals; and to exposing criminals to more criminals, breeding gang culture. Violent criminals surely merit our censure, extraction from society, and punishment. But that doesn't mean our hearts need to be full of a desire for vengeance.

|

| "Peace." Over the head of the angel of peace in Bruton Parish, Williamsburg, VA. |

I believe a society needs to be prepared to use force against those who would forcefully harm others. But increasingly I am coming to believe that individuals in each society also need to be prepared to fight fire not with fire but with the healing waters of love, waters that overflow from hearts that daily struggle to regard the people we most hate and fear as the people we also most need to love. It's not easy. But it may be the only way to become "a community at peace with itself."

*****

I have written two other posts about prisons, and Charles Peirce's reasons why our current system is a mark of insanity--or at least that it evinces a serious lack of love--here and here.