Mary Karr

- Virginia Woolf, Mrs. Dalloway. (Mixed feelings about this one. My mind enjoyed it more than my aesthetic sense did, if that makes sense.)

- John Steinbeck, Cannery Row and Of Mice and Men. (I discovered Steinbeck late in life, thanks to a friend's recommendation. I've also recently read his Log From The Sea of Cortez and Travels With Charley In Search Of America. I think these two will forever shape me as a writer.)

- Graham Greene, Our Man In Havana, The Quiet American, The Honorary Consul, Travels With My Aunt, The Power And The Glory. (I will let the number of titles speak for itself.)

- Alan Paton, Cry, The Beloved Country. (I was surprised by how contemporary this old book felt, and by how relevant to America an African book could feel.)

- The Táin. Because I have a thing for reading really old books, and this is one of the oldest from Europe.

- China Miéville, Kraken. (London. Magical realism. Bizarre and witty.)

- J. Mark Bertrand, Back On Murder (I don't read many detective novels, but I really enjoy Bertrand's prose.)

- Cormac McCarthy, The Road. (The final lines spoke to my salvelinus fontinalis -loving heart.)

- David James Duncan, The River Why (I've re-read this one a few times. If you like trout and philosophy, you might like this book.)

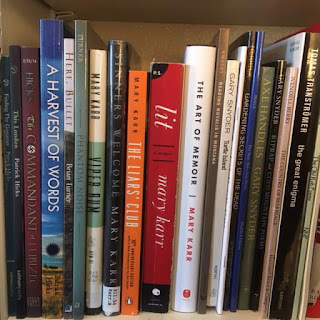

- Mary Karr, Lit. (Third in a series of memoirs. Some of the best storytelling I've read in a long time. Brilliant insights into addiction, love, and prayer.)

∞

The Slow, Important Work Of Poetry

At the time it seemed like chance that brought me to minor in comparative poetry in college.

Without having a master plan, over four years I wound up taking a number of poetry classes in four languages. Eventually I asked my college to consider them a new minor area of study. They agreed, and I graduated.

And then, slowly, over a quarter century, I began reading more poetry in more languages. It's always slow; I can't pick up a book of poems and read it like a novel. If the poetry is any good at all, I can read one or two poems, and then I've got to put the book down and let the words sit with me.

Often, I go back and read the same poem again, and again.

The very best poems I try to memorize, even though my memory for verse has never been good. I imagine most people would consider that a useless exercise, a waste of storage space in an already cluttered brain.

But in each season of my life I've found that it is some form of poetry that acts as salve to my soul's wounds or food that sustains its long journey forward. Homer's long story-poems; old epics and sagas from Ireland and Wales and Iceland; Vedic verses and Greek scriptures; Gregorian chants that have echoed in stone chambers for centuries; Shakespeare's or Petrarch's sonnets; the Psalms and proverbs of Hebrew priests and kings; a few words put together well by Dylan Thomas, Gary Snyder, Tomas Tranströmer, or C.S. Lewis; or the timely phrases of some of my favorite contemporaries like Patrick Hicks, Abigail Carroll, Mary Karr, Wendell Berry, Melissa Kwasny, John Lane, or Brian Turner. Each of them has, at some point, given me the daily bread I craved.

I can't seem to predict when the need will arise, but suddenly, there it is, and I find myself quoting Joachim du Bellay's sonnet about travel, and home:

That sonnet often reminds me, in turn, of verses about Abraham.

I am no good at praying, but I often wish I were. I think the fact that we make light of prayer - both by mocking those who pray and by being those who speak piously of prayer but who do not allow ourselves to confess the weakness prayer implies - says something of another shared longing, not unlike the longing for home. We long to comfort those far away when tragic events fall on them. They may be total strangers, but we know how horrible we would feel in their place, and we know that right now there is nothing we can do to staunch the flow of pain for them. But we can hold them in the center of our consciousness and, for a little while, not let any lesser thoughts crowd them out of our hearts and minds. We can, for a little while, consider our lives to be connected to theirs. We can, for a little while, ask ourselves what we might do to change the world so that this pain will not be inflicted on others.

Since I am not adept at praying, In those times I find the prayers of others buoy me up above the waves of emotional tempest. The prayer books of my tradition - the various versions of The Book of Common Prayer - often transform my anguish into something articulate. Of course, we turn to that same book when a baby is born, when a couple is wed, and when our beloved are interred. These events? We know they are coming, and yet it is not easy to prepare oneself, to be always ready for those days. I live in a tent; poetry often gives me a foundation to build on, and the better I've memorized it, the stronger that foundation becomes.

Those words, buried like seeds, slowly come to bear fruit in my life. Sometimes I wonder: was it really chance that brought me to the poems?

In the hardest of times, and also in the most joyful times, the words of poets are like a cup of water in a dry place. They refresh me, and they clear my throat so that I can take in that which sustains my own life, and speak other words, both old and new, that may sustain the lives of others.

Without having a master plan, over four years I wound up taking a number of poetry classes in four languages. Eventually I asked my college to consider them a new minor area of study. They agreed, and I graduated.

And then, slowly, over a quarter century, I began reading more poetry in more languages. It's always slow; I can't pick up a book of poems and read it like a novel. If the poetry is any good at all, I can read one or two poems, and then I've got to put the book down and let the words sit with me.

Often, I go back and read the same poem again, and again.

The very best poems I try to memorize, even though my memory for verse has never been good. I imagine most people would consider that a useless exercise, a waste of storage space in an already cluttered brain.

But in each season of my life I've found that it is some form of poetry that acts as salve to my soul's wounds or food that sustains its long journey forward. Homer's long story-poems; old epics and sagas from Ireland and Wales and Iceland; Vedic verses and Greek scriptures; Gregorian chants that have echoed in stone chambers for centuries; Shakespeare's or Petrarch's sonnets; the Psalms and proverbs of Hebrew priests and kings; a few words put together well by Dylan Thomas, Gary Snyder, Tomas Tranströmer, or C.S. Lewis; or the timely phrases of some of my favorite contemporaries like Patrick Hicks, Abigail Carroll, Mary Karr, Wendell Berry, Melissa Kwasny, John Lane, or Brian Turner. Each of them has, at some point, given me the daily bread I craved.

I can't seem to predict when the need will arise, but suddenly, there it is, and I find myself quoting Joachim du Bellay's sonnet about travel, and home:

Heureux qui, comme Ulysse, a fait un beau voyage

Ou comme cestuy-là qui conquit la toison

Et puis est retourné, plein d'usage et raison

Vivre entre ses parents le reste de son âgeHis simple words save me from forming new ones and free me to think and feel as the occasion demands; his words give utterance to what I find welling up inside me. His words change my homesickness into a stage in a worthwhile journey. Here is a very loose translation of those lines: "Happy is he who, like Ulysses, made a beautiful journey, or like that man who seized the Golden Fleece, and then traveled home again, full of wisdom, to live the rest of his life with his family." We are pulled in both directions at once: towards the Golden Fleece and adventures in Troy, and towards the home we left behind when we departed on our quest.

That sonnet often reminds me, in turn, of verses about Abraham.

Consider Abraham, who dwelled in tents,

because he was looking forward to a city with foundations.This longing for home that I sometimes have when I travel is itself no alien in any land. We all may feel it in any place. Everyone feels lost sometimes. Knowing that others have found words to express their feeling of being lost is itself a reminder that we are not alone. Hölderlin's opening words in his poem about St. John's exile on Patmos say this well:

Nah ist, und schwer zu fassen, der GottIt does seem that God - like home and family and love and neighbors - is close enough to grasp, so close that we could meaningfully touch them all right now. And yet so far that nothing but our words can draw near.

I am no good at praying, but I often wish I were. I think the fact that we make light of prayer - both by mocking those who pray and by being those who speak piously of prayer but who do not allow ourselves to confess the weakness prayer implies - says something of another shared longing, not unlike the longing for home. We long to comfort those far away when tragic events fall on them. They may be total strangers, but we know how horrible we would feel in their place, and we know that right now there is nothing we can do to staunch the flow of pain for them. But we can hold them in the center of our consciousness and, for a little while, not let any lesser thoughts crowd them out of our hearts and minds. We can, for a little while, consider our lives to be connected to theirs. We can, for a little while, ask ourselves what we might do to change the world so that this pain will not be inflicted on others.

Since I am not adept at praying, In those times I find the prayers of others buoy me up above the waves of emotional tempest. The prayer books of my tradition - the various versions of The Book of Common Prayer - often transform my anguish into something articulate. Of course, we turn to that same book when a baby is born, when a couple is wed, and when our beloved are interred. These events? We know they are coming, and yet it is not easy to prepare oneself, to be always ready for those days. I live in a tent; poetry often gives me a foundation to build on, and the better I've memorized it, the stronger that foundation becomes.

Those words, buried like seeds, slowly come to bear fruit in my life. Sometimes I wonder: was it really chance that brought me to the poems?

In the hardest of times, and also in the most joyful times, the words of poets are like a cup of water in a dry place. They refresh me, and they clear my throat so that I can take in that which sustains my own life, and speak other words, both old and new, that may sustain the lives of others.

∞

Books Worth Reading

After my recent post about great books, pedagogy and hope I've had some queries about what I'm reading and what I recommend.

I'm reluctant to make book recommendations because I think what you read should have some connection to what you care about and what you've already read. In general, my recommendations are these:

First, I agree with what C.S. Lewis once said:* it's good to read old books. Old books and books written by people who are not like us have a remarkable power of helping us to see the world with fresh eyes.

Second, let your reading grow organically. If you liked a book you read, let it lead you to the next book you read. Often, books name their connections to other books. Or authors will name those connections, dependencies, and appreciations. The first time I read Lewis's Out of the Silent Planet, I missed the fact that the preface named H.G. Wells and that the afterword referred to Bernardus Silvestris. When I read it again as an adult, I caught those obvious references and let them lead me to other books.**

Third, I recommend learning the classics. That's an intentionally vague term, and I use it to mean that it's good to know those books that have given your culture its vocabulary. People who have stories in common have enriched possibilities for conversation. One of my favorite Star Trek episodes explored this idea, and it appealed to me because I believe that it's not far from how language really grows. If you need a place to start, check out one of the various lists of "great books" floating around out there. For instance this one, or this one.

With all that being said, if you're still interested in what I'm reading, here are some older titles I've enjoyed in the last year or so:

* Lewis said this in his introduction to Athanasius' On The Incarnation (which, by the way, is now available from SVS Press in a dual-language edition, Greek on one page, English on the facing page.)

** There are two excellent books on Lewis' "Space Trilogy" or (as I think it should be called) "Ransom Trilogy": This one by Sanford Schwartz, and this one by David Downing.

I'm reluctant to make book recommendations because I think what you read should have some connection to what you care about and what you've already read. In general, my recommendations are these:

First, I agree with what C.S. Lewis once said:* it's good to read old books. Old books and books written by people who are not like us have a remarkable power of helping us to see the world with fresh eyes.

Second, let your reading grow organically. If you liked a book you read, let it lead you to the next book you read. Often, books name their connections to other books. Or authors will name those connections, dependencies, and appreciations. The first time I read Lewis's Out of the Silent Planet, I missed the fact that the preface named H.G. Wells and that the afterword referred to Bernardus Silvestris. When I read it again as an adult, I caught those obvious references and let them lead me to other books.**

Third, I recommend learning the classics. That's an intentionally vague term, and I use it to mean that it's good to know those books that have given your culture its vocabulary. People who have stories in common have enriched possibilities for conversation. One of my favorite Star Trek episodes explored this idea, and it appealed to me because I believe that it's not far from how language really grows. If you need a place to start, check out one of the various lists of "great books" floating around out there. For instance this one, or this one.

With all that being said, if you're still interested in what I'm reading, here are some older titles I've enjoyed in the last year or so:

*****

* Lewis said this in his introduction to Athanasius' On The Incarnation (which, by the way, is now available from SVS Press in a dual-language edition, Greek on one page, English on the facing page.)

** There are two excellent books on Lewis' "Space Trilogy" or (as I think it should be called) "Ransom Trilogy": This one by Sanford Schwartz, and this one by David Downing.

*****

I realize I'm posting a lot about Great Books and St John's College lately. I'll stop soon. They don't pay me for this; I'm just a grateful alumnus.

*****

Update, 8/11/14: I've posted another list like this one on my blog, with new recommendations. You can find it here.

∞

Prayer and Forgiveness

Years ago I was wronged by someone I worked with. The details don't matter, because as Viktor Frankl says, pain is like a gas, expanding to fill the available space. Even if it was a small offense, it swelled until it filled me.

I told a friend about it, who listened patiently to my story. When I was done, he said, sympathetically, "You need to pray for him and ask God to bless him."

What I had hoped to hear was something more like "Wow, what a waste of skin that guy is. Your anger is justified."

Now that I have the increasing clarity that comes when time separates us from painful events, I think my friend was right. His idea of God is that God wants all of us to be better than we are.

Praying for my former co-worker has allowed me to remove him from the center of my consciousness, where his image lived as a threatening villain, and to think of him as someone in need of healing and transformation. Blessing him has given me a way to articulate my desire to see him change and become a kinder person, for everyone's sake.

No doubt theology matters here. In plainer terms, how we imagine the God we pray to matters, because that will shape the way we act towards others. At the risk of declaring the obvious: what we think about God has consequences for the way we live with other people. In her book, Lit, Mary Karr talks about a friend who tells her that God doesn't have a plan for her, God has a dream for her. God wants good things for her.

That's an attractive idea of God, one who wants us to forgive others so we can be set free from their tyranny; and one who wants us to bless others so that we can begin to see ourselves as agents of positive change rather than as victims.

I told a friend about it, who listened patiently to my story. When I was done, he said, sympathetically, "You need to pray for him and ask God to bless him."

What I had hoped to hear was something more like "Wow, what a waste of skin that guy is. Your anger is justified."

Now that I have the increasing clarity that comes when time separates us from painful events, I think my friend was right. His idea of God is that God wants all of us to be better than we are.

Praying for my former co-worker has allowed me to remove him from the center of my consciousness, where his image lived as a threatening villain, and to think of him as someone in need of healing and transformation. Blessing him has given me a way to articulate my desire to see him change and become a kinder person, for everyone's sake.

No doubt theology matters here. In plainer terms, how we imagine the God we pray to matters, because that will shape the way we act towards others. At the risk of declaring the obvious: what we think about God has consequences for the way we live with other people. In her book, Lit, Mary Karr talks about a friend who tells her that God doesn't have a plan for her, God has a dream for her. God wants good things for her.

That's an attractive idea of God, one who wants us to forgive others so we can be set free from their tyranny; and one who wants us to bless others so that we can begin to see ourselves as agents of positive change rather than as victims.