Matthew Davis

∞

Against Grading

One of the best things to happen in my education was when I attended a school - a graduate school - that refused to give grades. "How is that possible?" you may ask. "What kind of fluffy, feel-good, no-good education did you get there?" To which I reply: a damn good one; one of the best. Curious? Read on:

We are sick with love of enumeration. We've discovered that counting things over time is a powerful way to predict what will happen next. And now we are mantic-obsessives, (that's not a typo) that is, people obsessed with prediction, with foresight that will rule the uncertainty of our lives.

Look: that's not such a bad thing, in a way. What I'm describing is the root and trunk of science: quantification and statistical analysis is the beating heart of our understanding of scientific laws, which are about predictive inference. Understanding of the laws of nature can save lives, and make water clean, and heal some deep wounds. Science is wonderful, and no liberal education should stint in its science offerings.

But if we're not careful - if we divorce science and enumeration from other ways of regarding value - that can make some pretty big holes in the world, too. (Whenever I hear someone say that religion is the cause of human suffering, I think "What about chemistry?" Both religion and chemistry can be deployed to change lives, and to change them dramatically. Or to end them suddenly.)

Likewise enumeration. The counting of things can give us great power to rule our own futures. It can also give us great power to rule the futures of others, and not always in kind ways. One real danger of learning to count things is that we find it too easy to shift from saying "It's hard to count X" to saying "X doesn't count."

Our quantifimania, for instance, has half of us (no, I didn't count, I'm speaking figuratively) believing that good teaching can be measured by test scores. Or that someone's intelligence can be reduced to a simple number. Or that a kid's giftedness, or ability to learn, or likelihood of living a creative and thoughtful life can be simply reduced to a GPA or a standardized test score.

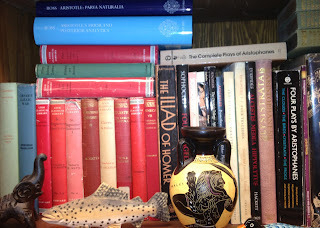

Years ago, when I was thinking about beginning my graduate studies in Philosophy, a professor I knew suggested I prepare for my Ph.D. by attending St John's College's "Great Books" program. I looked over the reading list and realized that even if it didn't get me into a Ph.D. program, it would be worth it for its own sake.

As an undergraduate at an elite liberal arts college in the northeast, I was continually reminded that little mattered more than my grades. I was the sort of student who earned good grades with little effort, so it was natural to begin to believe that what mattered most came without struggle. As a result - I realize this now, in hindsight - I bypassed much of the opportunity my college offered me by studying only what my classes required of me.

This all changed in my first term at St John's, when I wrote a seminar paper on Aristotle. My tutor Matt Davis returned it to me without a grade on it. Instead, it was covered with marginal comments, underlining, and a paragraph of reflection and response at the end. But again, no grade. "How did I do?" I asked him. "Have a look at what I wrote," he replied. Sure enough, he told me how I did: here were the things that were strong; here were the gaps in my argument. No quantification, just explanation.

I wanted a grade because I'd been habituated to thinking of the grade as the way of judging the merit of my work. St John's decision to refuse to give grades is an intentional and hard-fought resistance to that way of thinking.

At the end of the term, each of my tutors gave me one, two, or even three pages of handwritten comments on my strengths and weaknesses as a student. But once again, no grades. Nothing to distract me from reading their comments, nothing that would allow me to measure the worth of their comments other than the comments themselves. And nothing to make me think: "Well, that's done."

As a result, I stopped thinking about grades and started thinking about ideas, and texts, and writing. I started caring more about correcting my ignorance than about concealing it from my peers and teachers. And I stopped thinking about learning as something that happens in fifteen-week segments. Learning was no longer something that begins here and ends there. Learning was now a river I step into, and in which I may swim, and bathe, and drink for as long as I am able. And if I step out, it remains there, ever flowing, for me to return to.

It was only then that I realized just how bored I had been in school. I had been bored since my childhood, because I had to show up, had to perform tasks, in order to get these lofty numbers that weighed so heavily and meant so little to me personally.

I've known many students who are bright but who don't do well on standardized tests. I've known many others who don't do well on any test at all, and I've no doubt that much of it has to do with anxiety over the way their work will be reduced to a number, one they feel is so disconnected from what they know. As a teacher I feel I'm constantly fighting to get my students to stop worrying about their grades, even while I'm required to assign grades to their work. Grades are, in my opinion, one of the worst things to happen to education. This is not to say I'm against evaluation or helpful feedback. I'm all for them, in fact. Which is why I'm so opposed to the damnable, lazy practice of reducing that evaluation to what can be easily counted.

The ancients tell us that King David sinned against God by counting his fighting men. (Here, too.) I think the sin was not the counting, but the way his counting became a basis for policy, and so for value. When we weigh our forces before going to war, the question shifts from "Is this a war worth fighting?" to "Can I win?" Both of those are important questions, but God save us from ever making the latter so important that we think of the former as a question that doesn't count. That kind of thinking turns people into instruments of war rather than free individuals; people become pawns, tools of policy, and they become as expendable as they are enumerable. When we dare to quantify our gains and losses in terms of numbers of human lives expended, we have already lost something important that may be very hard to regain.

And God save us, likewise, from thinking of our lives as things to be measured, and measured against others' lives. God save us from thinking of meaningful work as something to be done against a time clock, from thinking of wealth as something to be measured in numbers rather than in a richness of life. And God save us teachers and citizens from thinking that the worth of a woman or a man can easily be measured by the grades they have earned, or that the predictions we may make on the basis of those grades should have the power of prophecy.

*****

We are sick with love of enumeration. We've discovered that counting things over time is a powerful way to predict what will happen next. And now we are mantic-obsessives, (that's not a typo) that is, people obsessed with prediction, with foresight that will rule the uncertainty of our lives.

Look: that's not such a bad thing, in a way. What I'm describing is the root and trunk of science: quantification and statistical analysis is the beating heart of our understanding of scientific laws, which are about predictive inference. Understanding of the laws of nature can save lives, and make water clean, and heal some deep wounds. Science is wonderful, and no liberal education should stint in its science offerings.

But if we're not careful - if we divorce science and enumeration from other ways of regarding value - that can make some pretty big holes in the world, too. (Whenever I hear someone say that religion is the cause of human suffering, I think "What about chemistry?" Both religion and chemistry can be deployed to change lives, and to change them dramatically. Or to end them suddenly.)

Likewise enumeration. The counting of things can give us great power to rule our own futures. It can also give us great power to rule the futures of others, and not always in kind ways. One real danger of learning to count things is that we find it too easy to shift from saying "It's hard to count X" to saying "X doesn't count."

Our quantifimania, for instance, has half of us (no, I didn't count, I'm speaking figuratively) believing that good teaching can be measured by test scores. Or that someone's intelligence can be reduced to a simple number. Or that a kid's giftedness, or ability to learn, or likelihood of living a creative and thoughtful life can be simply reduced to a GPA or a standardized test score.

Years ago, when I was thinking about beginning my graduate studies in Philosophy, a professor I knew suggested I prepare for my Ph.D. by attending St John's College's "Great Books" program. I looked over the reading list and realized that even if it didn't get me into a Ph.D. program, it would be worth it for its own sake.

As an undergraduate at an elite liberal arts college in the northeast, I was continually reminded that little mattered more than my grades. I was the sort of student who earned good grades with little effort, so it was natural to begin to believe that what mattered most came without struggle. As a result - I realize this now, in hindsight - I bypassed much of the opportunity my college offered me by studying only what my classes required of me.

This all changed in my first term at St John's, when I wrote a seminar paper on Aristotle. My tutor Matt Davis returned it to me without a grade on it. Instead, it was covered with marginal comments, underlining, and a paragraph of reflection and response at the end. But again, no grade. "How did I do?" I asked him. "Have a look at what I wrote," he replied. Sure enough, he told me how I did: here were the things that were strong; here were the gaps in my argument. No quantification, just explanation.

I wanted a grade because I'd been habituated to thinking of the grade as the way of judging the merit of my work. St John's decision to refuse to give grades is an intentional and hard-fought resistance to that way of thinking.

At the end of the term, each of my tutors gave me one, two, or even three pages of handwritten comments on my strengths and weaknesses as a student. But once again, no grades. Nothing to distract me from reading their comments, nothing that would allow me to measure the worth of their comments other than the comments themselves. And nothing to make me think: "Well, that's done."

As a result, I stopped thinking about grades and started thinking about ideas, and texts, and writing. I started caring more about correcting my ignorance than about concealing it from my peers and teachers. And I stopped thinking about learning as something that happens in fifteen-week segments. Learning was no longer something that begins here and ends there. Learning was now a river I step into, and in which I may swim, and bathe, and drink for as long as I am able. And if I step out, it remains there, ever flowing, for me to return to.

It was only then that I realized just how bored I had been in school. I had been bored since my childhood, because I had to show up, had to perform tasks, in order to get these lofty numbers that weighed so heavily and meant so little to me personally.

I've known many students who are bright but who don't do well on standardized tests. I've known many others who don't do well on any test at all, and I've no doubt that much of it has to do with anxiety over the way their work will be reduced to a number, one they feel is so disconnected from what they know. As a teacher I feel I'm constantly fighting to get my students to stop worrying about their grades, even while I'm required to assign grades to their work. Grades are, in my opinion, one of the worst things to happen to education. This is not to say I'm against evaluation or helpful feedback. I'm all for them, in fact. Which is why I'm so opposed to the damnable, lazy practice of reducing that evaluation to what can be easily counted.

The ancients tell us that King David sinned against God by counting his fighting men. (Here, too.) I think the sin was not the counting, but the way his counting became a basis for policy, and so for value. When we weigh our forces before going to war, the question shifts from "Is this a war worth fighting?" to "Can I win?" Both of those are important questions, but God save us from ever making the latter so important that we think of the former as a question that doesn't count. That kind of thinking turns people into instruments of war rather than free individuals; people become pawns, tools of policy, and they become as expendable as they are enumerable. When we dare to quantify our gains and losses in terms of numbers of human lives expended, we have already lost something important that may be very hard to regain.

And God save us, likewise, from thinking of our lives as things to be measured, and measured against others' lives. God save us from thinking of meaningful work as something to be done against a time clock, from thinking of wealth as something to be measured in numbers rather than in a richness of life. And God save us teachers and citizens from thinking that the worth of a woman or a man can easily be measured by the grades they have earned, or that the predictions we may make on the basis of those grades should have the power of prophecy.

∞

Great Books, Pedagogy, and Hope

Great Books and the Great Conversation

About fifteen years ago I enrolled in the "Great Books" M.A. program at St John's College in Santa Fe, New Mexico. It was one of the best decisions I've ever made.

Much as I appreciate my undergraduate education, too often it rewarded me for concealing my ignorance and emphasizing what I already knew. The problem, of course, is that my ignorance was thus shielded from the sterilizing sunlight of others' scrutiny and instruction.

Confessing Our Ignorance

Matthew Davis, my tutor and advisor at St John's, won me over to another way of viewing literature when, on one of the first days we met, he pointed to a passage in Plato's Republic and said "I have always wondered what Plato means by that." Looking up at the class, he asked, "Do any of you have any ideas about what he might be trying to say?"

Mr. Davis is the first professor I recall who openly confessed his ignorance, and who thereby modeled what it means to open oneself to the instruction of a great text. Not much has shaped my academic life as much as that.

Grappling With Classic Texts

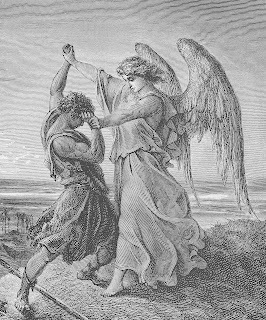

As I have begun to mature into my own place as a teacher, I often think that this is the best thing I can give my students: not professorial and authoritative descriptions of texts, but an example of what it means to be a student. I can try to be an example of someone who sits with texts and listens to them, grappling with them, like Jacob with the angel or like Menelaus with Proteus: persistently grappling with my superior and refusing to let go until I receive a blessing. (Selah.)

For the last few years I have been seeking out and reading classic novels. As I read them I feel like an apprentice architect touring buildings, looking not just at the outward form and function but looking for the supporting structure, trying to notice the decisions the artist made about what to include and what to omit.

Along the way, I have begun trying to write bits of dialogue, scenes, characters, and other elements of fiction. I'm not trying to write a novel so much as trying to perform experiments the way high school science students do in labs: not to discover something new but to learn haptically, kinesthetically, experientially what the masters already know. I can't say that I've learned to write novels, so don't expect anything from me there. But as I've paid attention, I feel I've begun to squeeze some blessings out of the books, including some unexpected ones.

I've noticed, for instance, that Craig Nova writes about the olfactory sense in a way that makes me notice aromas I never noticed before. John Steinbeck has begun to make me care more about friendship, and about the people in front of me. Harold Frederic has me rethinking my early faith, and this is helping me look ahead as I try to nurture it into a faith worth having. Novels are helping me see the world differently.

So What Does This Have To Do With Hope?

I just finished Graham Greene's The Honorary Consul. Apparently this was Greene's favorite of his own works, and I can see why. Like many of the really good novels I've read, it has left me thinking about a range of topics, and longing for someone to talk about it with.

Which brings me to hope. I started reading Greene because Bill Swart, my friend and colleague, told me about how good Greene's novels are. Bill was right about this, so I sought him out the other day to talk more about Greene. We said too much to cover it all here, but Bill said something I can't bear not to repeat. When we began discussing Greene's The Power and the Glory, Bill said "That book gave me hope that my own self-perception might be wrong."

If you know the novel, you know why, because you know how Greene's characters wrestle with being both sinners and saints. If you don't know the novel, let me recommend it to you.

We Should Keep Teaching And Reading Fiction

I still have a lot to learn about novels. I doubt I'll ever write one - or a good one, anyway. But I'm delighting in reading them. Perhaps that's why they matter so much: they delight us, and capture us. When I'm in a good book I feel like I'm really in it. I stop seeing words on a page and start seeing, with some inner eye, the world the novelist sees.

And like all my other travels, journeys into fiction leave me a different person. I see different possibilities, I see -- and smell -- my world differently. I know it's important to teach young people to read non-fiction, but teaching fiction might be for them what The Power and the Glory was for Bill: a tonic for his soul, a sweet drink of hope that didn't just entertain, but that allowed him to envision his life, his work, and his purpose in an entirely new way.

About fifteen years ago I enrolled in the "Great Books" M.A. program at St John's College in Santa Fe, New Mexico. It was one of the best decisions I've ever made.

Much as I appreciate my undergraduate education, too often it rewarded me for concealing my ignorance and emphasizing what I already knew. The problem, of course, is that my ignorance was thus shielded from the sterilizing sunlight of others' scrutiny and instruction.

Confessing Our Ignorance

Matthew Davis, my tutor and advisor at St John's, won me over to another way of viewing literature when, on one of the first days we met, he pointed to a passage in Plato's Republic and said "I have always wondered what Plato means by that." Looking up at the class, he asked, "Do any of you have any ideas about what he might be trying to say?"

Mr. Davis is the first professor I recall who openly confessed his ignorance, and who thereby modeled what it means to open oneself to the instruction of a great text. Not much has shaped my academic life as much as that.

Grappling With Classic Texts

As I have begun to mature into my own place as a teacher, I often think that this is the best thing I can give my students: not professorial and authoritative descriptions of texts, but an example of what it means to be a student. I can try to be an example of someone who sits with texts and listens to them, grappling with them, like Jacob with the angel or like Menelaus with Proteus: persistently grappling with my superior and refusing to let go until I receive a blessing. (Selah.)

For the last few years I have been seeking out and reading classic novels. As I read them I feel like an apprentice architect touring buildings, looking not just at the outward form and function but looking for the supporting structure, trying to notice the decisions the artist made about what to include and what to omit.

Along the way, I have begun trying to write bits of dialogue, scenes, characters, and other elements of fiction. I'm not trying to write a novel so much as trying to perform experiments the way high school science students do in labs: not to discover something new but to learn haptically, kinesthetically, experientially what the masters already know. I can't say that I've learned to write novels, so don't expect anything from me there. But as I've paid attention, I feel I've begun to squeeze some blessings out of the books, including some unexpected ones.

I've noticed, for instance, that Craig Nova writes about the olfactory sense in a way that makes me notice aromas I never noticed before. John Steinbeck has begun to make me care more about friendship, and about the people in front of me. Harold Frederic has me rethinking my early faith, and this is helping me look ahead as I try to nurture it into a faith worth having. Novels are helping me see the world differently.

So What Does This Have To Do With Hope?

I just finished Graham Greene's The Honorary Consul. Apparently this was Greene's favorite of his own works, and I can see why. Like many of the really good novels I've read, it has left me thinking about a range of topics, and longing for someone to talk about it with.

Which brings me to hope. I started reading Greene because Bill Swart, my friend and colleague, told me about how good Greene's novels are. Bill was right about this, so I sought him out the other day to talk more about Greene. We said too much to cover it all here, but Bill said something I can't bear not to repeat. When we began discussing Greene's The Power and the Glory, Bill said "That book gave me hope that my own self-perception might be wrong."

If you know the novel, you know why, because you know how Greene's characters wrestle with being both sinners and saints. If you don't know the novel, let me recommend it to you.

We Should Keep Teaching And Reading Fiction

I still have a lot to learn about novels. I doubt I'll ever write one - or a good one, anyway. But I'm delighting in reading them. Perhaps that's why they matter so much: they delight us, and capture us. When I'm in a good book I feel like I'm really in it. I stop seeing words on a page and start seeing, with some inner eye, the world the novelist sees.

And like all my other travels, journeys into fiction leave me a different person. I see different possibilities, I see -- and smell -- my world differently. I know it's important to teach young people to read non-fiction, but teaching fiction might be for them what The Power and the Glory was for Bill: a tonic for his soul, a sweet drink of hope that didn't just entertain, but that allowed him to envision his life, his work, and his purpose in an entirely new way.