Matthew Dickerson

- Richard Russo, Straight Man. This is one that has been recommended to me so many times by so many people I finally bought it and read it. If you work in a small college humanities department, trust me: you'll feel at home in this book.

- J. M. Coetzee, Elizabeth Costello. This is another that was recommended to me. It takes the form of a series of lectures delivered by a novelist, with very little framing around each lecture. The lectures stand alone, but all together they give the picture of an artist at work trying to figure out what exactly she is doing, what she believes, and why. Coetzee is really a philosophical novelist, and he does a remarkable job of engaging directly with figures like Descartes and Kant and Peter Singer.

- Dave Eggers, How We Are Hungry. Eggers' short stories are like David Foster Wallace's, but less frenetic and wild and so a little easier to read. I love the genre, and I'm always fascinated by people like Eggers and Wallace who explore its edges. I don't love this book, but it has kept my attention as a kind of intellectual exercise, and it is like a garden filled with tiny blossoms that delight the eye when you slow down and look closely.

- Matthew Dickerson, The Rood And The Torc. Dickerson is a friend of mine and my co-author, so there's my disclosure. Now let me say this about Dickerson: there are good reasons why he's my friend and my co-author, and this book illustrates some of them. He's a natural, easy storyteller who makes you glad you kept turning the pages. His prose is light, disappearing from the eye, easily replaced with a mental image of the place and the characters. This is one of several novels he has written about the peripheries of Beowulf, a beautiful story about poetry, songs, medieval Europe, and the cost of making the right choices. Reading this book was the first time I felt like I could see medieval life, not just read about it. Homes and hearths come alive with smoke and roasting meat and moving songs; the Frisian landscape and the rolling sea and the smell of cowherds seem to lift off the pages and into my imagination as I read it. John Wilson is right: this is "a splendid historical novel." Dickerson is brilliant, and so is his prose.

-

Hunter S. Thompson, Screwjack. This is the book Carlos Castaneda would have written if he'd admitted he was writing fiction. You feel the intoxication, and you believe it.

- Herman Melville, Moby Dick. This is one of those books that everyone knows and nearly nobody reads. It is long, and full of words. Lots and lots of words. But wow. It is one of those rare books that gives me the sense that every sentence was the child of long and serious reflection. Reading this was like taking a really good class. Naturally, I bought myself a "What Would Queequeg Do?" t-shirt to mark this milestone in my life. You can get yours here.

- Nathaniel Hawthorne, Mosses From An Old Manse. And this is like Melville. You read it because at the end, you discover that what seemed to be a simple story about a simple thing makes you understand your world a lot better.

- John Steinbeck, The Moon Is Down. I love Steinbeck, so I bought this book not knowing a thing about it. Turns out Steinbeck wrote it as a propaganda piece. He wanted to give a picture of what it would look like to live in, say, Norway or Denmark under Nazi rule, and how that occupation could lead to resistance. What I love about Steinbeck is, more than anything, his desire to portray people with sympathy. The Nazis in his book are real people, believable, and even likeable. I wish we had more people able to portray our contemporary enemies with such sympathy. If we could do so, we could love them better, and I think we could better understand how to resist them. As a bonus, towards the end of the novel there is a prolonged reflection on the meaning of Plato's Apology of Socrates.

- Patrick Hicks, The Commandant of Lubizec. (Another disclosure: Hicks is also my friend.) I was pretty sure I'd read all I needed to read about the Holocaust. I grew up with survivors. I've read all the usual books, I teach several in my classes. I didn't want to hear any more. But Hicks has done something truly remarkable in this fictionalized account of Operation Reinhard. In fact, what he's done is similar to what Steinbeck does: he has written about people with real sympathy and insight. It's a hard read because he spares us nothing, but that's precisely what makes it such a good read. Here's a short video about the book:

- This too is related to technology, of course. If the class is focused on video screens, then all the chairs will face the screens, and the classroom might even be structured like a theater. Etymologically, "theater" means something like "a place of gazing," and theaters tend to encourage people to gaze. Sometimes this can work against other activities, like colloquy, small-group interaction, and really anything that involves students moving from one place to another.

- If that last sentence made you ask,"But why do you want your students to move from one place to another?" then you see that we have some pretty strong presuppositions about how education should happen: students should sit and listen, teachers should stand and lecture. This communicates something about authority, and at times that's helpful. But it can also invite students to lean back into passivity, and to assume they have no role in their own education.

- The furniture in classrooms tells us how people are to behave, because it has been made and purchased by people who had in mind some idea of how students should behave. Most wrap-around desks are made for right-handed people, for instance. And most classroom desks I've seen expect students to sit upright, at attention, with a book open in front of them. I really don't like those desks, and I feel trapped when I sit in them. I wonder sometimes how they make my students feel. I wish we had fewer chairs and more sofas. Maybe a fireplace, or some tables with glasses of water, and ashtrays on them. I suppose I wish I could teach in pubs or ratskellers, which are, after all, places consciously designed for people to meet and discuss what most matters to them, informally, passionately, amicably.

- Classrooms that privilege video screens tend to undervalue natural light and windows. I am reminded of Emerson's reflection on a boring sermon he once heard. Emerson wrote, in his Divinity School Address, that while the minister droned on, Emerson looked out the window at the falling snow, which, he proclaimed, preached a better sermon than the minister. I have no doubt that nature can often give a better lecture than I can.

∞

In terms of ethics and law: who has access to the information confessed, and what is the legal status of that confession? Is there anything like the privilege of confidentiality enjoyed by clergy who hear private confessions from their parishioners?

*****

Update, 22 May 2018: Irina Raicu just published a very thoughtful reply to this, entitled "Parenting, Politeness, Poets, and Priests" at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University. Her article is very much worth the time it will take you to read it. You may find it here.

The Ethics of Automation: Poetry and Robot Priests

Philosophy professor Evan Selinger posted a question on Twitter yesterday about whether there are jobs that it would be unethical to automate.

As I am a Christian, an ethicist, and a philosopher of religion, this is

something I’ve been pondering for a few years: is there a case to be

made for automating the work of clergy?

A

German company recently automated a confessional. On the one hand, this

might have great therapeutic effects. On the other hand, it raises a

number of ethical, legal, and theological questions.

In terms of ethics and law: who has access to the information confessed, and what is the legal status of that confession? Is there anything like the privilege of confidentiality enjoyed by clergy who hear private confessions from their parishioners?

On the theological and ecclesiastical side: can a

meaningful confession be heard by someone who cannot sin, or does

confession depend on making a confession to a member of one’s own

community and church? Can a machine be a member of a church, or does it

have something more like the status of a chalice or a chasuble –

something the community uses liturgically but that does not have

standing in the deliberations and practices of the community? Another

important question: can a machine act as a vicar? That is, can a machine

stand in as a representative of God and proclaim the forgiveness of God

as we believe those who have been ordained may do?

Despite

the many weaknesses of religion, one strength of religion is that it

moves slowly. Yes, this too is a weakness at many times, but it is good

to move slowly when declaring sainthood, for instance. That’s a

decision that we should make carefully. Think about it like this: if we

are saying that person X is an example of good conduct, shouldn’t we

consider that person very carefully, from as many points of view as

possible, and do so after that person’s life has ended and all testimony

has been heard? Similarly, most religious traditions take time to

consider carefully whether someone should be ordained as clergy. In my

tradition, we speak of this as the “process of discernment,” and it is a

process that can take years, and that involves the whole community.

The downside is that this process is slow. The upside is that it keeps

us from making rash decisions, or at least it helps us to make fewer

rash decisions. We aren’t perfect.

My

first, gut response to Selinger’s question was that we should not outsource the writing of poetry to machines. My concerns here are twofold: one has to

do with the danger of persuasion: not much moves us as powerfully as

poetry does. My second concern is about the importance of having out

arts be the expressions of the heart of our communities. But I could be

wrong: maybe robots should be writing poetry – their own poetry, from

one machine to another. I do not wish to deprive anyone of the right to

artistic expression, nor do I wish to deprive envy community of the

right to have its own forms of beauty. Still, I worry about the way a

machine could be used to produce arrangements of words, sounds, and

images that would persuade us to act as we should not.

My

second response to Selinger’s question is related to the first: poetry is

at the heart of most religions, and I find myself with a hesitant

uncertainty about whether we should allow robots to be priests.

It’s

not that I think we should be unwilling to automate the tedious parts

of clerical work. In fact, that might be a real boon to the community.

We have allowed automation in many areas that has benefited us: bank

tellers and airline pilots have given up portions of their work to

reliable machines, and the result has been convenience and increased

safety. Why could a robot not also tend the sick and the needy, read to

those in hospice, visit those in prison, and so on? As I've written before, my wife is an Episcopal priest, and her work can be very demanding. There might be some parts of it that could be automated, freeing her up for other work that only people can do.

My

concern is not about the feasibility of having machines do this work.

On the whole, I’m in favor of it. But I do worry that if we hand over

caring for others to our machines, we might do so to our own detriment.

We should use the technologies we have to serve those in need. Of this I

have no doubt. But we should not pretend that in so doing we have done

all that we must do. I agree with Dr. King and Gandhi on this: we

ourselves need to care for those in need. Caring for those in need is

not a one-way transaction that serves only the sick and the poor; it is

something that the powerful and hale need as well.

I

have more to say about all of this, so this post is a too-hasty start,

but I want to risk continuing Evan Selinger’s conversation rather than risk

neglecting it. Evan has raised for us one of the more important

questions the current generation will face, I think.

For

right now, I will end this post by returning to poetry and mythology,

which is, as I said, a powerful resource for thinking about how we will

act. We need poetry, and we need to reflect on it together to sort out

the good poems from the bad. I’ll mention it here for your reflection:

J.R.R. Tolkien reflected on the poems of Genesis by creating his own

myth of creation in the Silmarillion. One element of that creation story

that my co-author Matthew Dickerson and I often return to is the story

in which one of God’s creations imitates God in making more sentient

beings, without God’s explicit permission. Here’s the passage I have in

mind:

“The making of things is in my heart from my own making by thee; and the child of little understanding that makes a play of the deeds of his father may do so without thought of mockery, but because he is the son of his father.”

Might it be possible for us also to make sentient life in imitation of God "without thought of mockery," and, if so, might it be that those lives we make could write poems and become priests? As anyone who has read Tolkien's myth knows, this raises a new set of ethical questions that now have to be resolved.--J.R.R. Tolkien, Silmarillion, p 43

*****

Update, 22 May 2018: Irina Raicu just published a very thoughtful reply to this, entitled "Parenting, Politeness, Poets, and Priests" at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University. Her article is very much worth the time it will take you to read it. You may find it here.

∞

More Books Worth Reading

One of the great pleasures of being a teacher is reading. To do my job well, I have to read. If I don't read a lot, I won't keep up with my field and I'll be a poorer teacher. Fortunately, I like reading.

Even so, one of the great surprises of being a teacher is that, at the end of a long day of work reading, I like to unwind with a good book. Go figure.

The last few months have brought me a surfeit of good books to unwind with. Here are some of the recent books I've enjoyed:

Even so, one of the great surprises of being a teacher is that, at the end of a long day of work reading, I like to unwind with a good book. Go figure.

The last few months have brought me a surfeit of good books to unwind with. Here are some of the recent books I've enjoyed:

∞

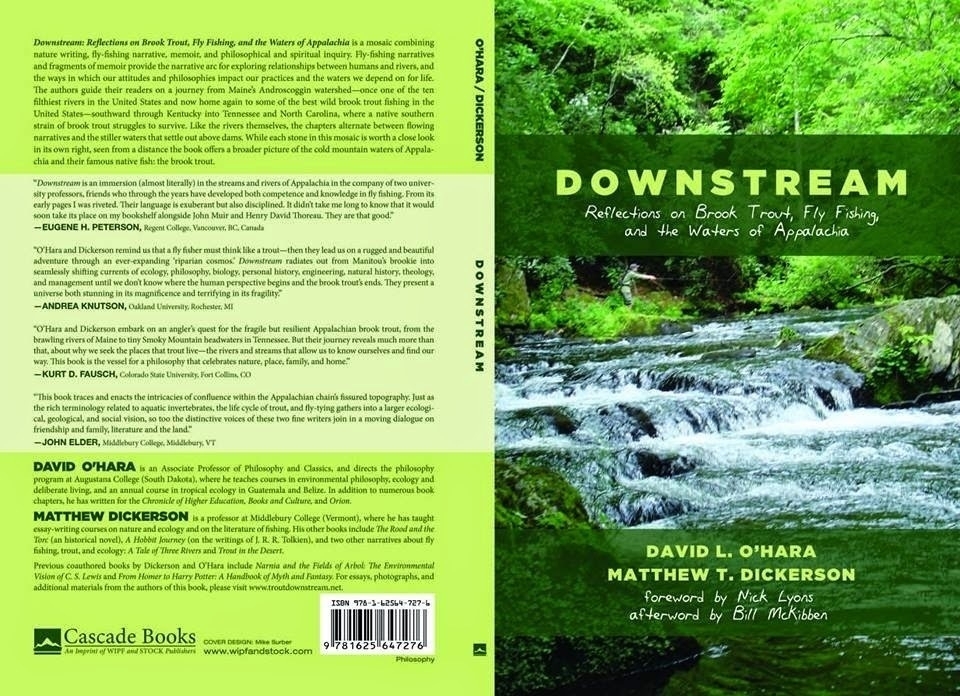

Downstream: My New Book On Brook Trout and Appalachian Ecology

You can find it here, on the publisher's website, for a very reasonable price.

It is now listed on Amazon as well, though not yet in stock there.

I'm very grateful for the foreword by Nick Lyons, the afterword by Bill McKibben, and the kind words offered by such a wide range of brilliant scholars of theology, literature, and science, like Eugene Peterson, Andrea Knutson, Kurt Fausch, and John Elder.

It is now listed on Amazon as well, though not yet in stock there.

I'm very grateful for the foreword by Nick Lyons, the afterword by Bill McKibben, and the kind words offered by such a wide range of brilliant scholars of theology, literature, and science, like Eugene Peterson, Andrea Knutson, Kurt Fausch, and John Elder.

∞

As September approaches, people keep asking me, "Are you ready to get back in the classroom?"

As early as middle school I knew I wanted to become a college professor, and I love my job. It is a delight to spend time with young people who are curious, after all.

Years ago, my friend Matt Dickerson pointed out to me that it's also my job to help those who are not curious to see why they should be. As it turns out, that work is usually delightful, too, a rewarding challenge.

So on the whole, I love my work.

But I admit I don't love classrooms, for several reasons:

First, no matter what decade, every classroom I've been in has exhibited an unhealthy tendency towards becoming cluttered with the latest technology, and most of that tech seems to take up a lot of space and to become the center of attention. I'm not opposed to technology in the classroom, not at all. But I'm opposed to letting it get in the way, as it does when the "Smart Cart" leaves me no room for my lecture notes, or when I can't seem to turn the ceiling-mounted projector on or off. I'm a fan of chalk, because chalk allows spontaneity, and it allows for much more than alphanumeric writing in neat rows. Sadly, concerns about chalk dust getting into computers is threatening to make chalkboards disappear from my classrooms. Alas. Chalk is an excellent technology, and if it vanishes, I will mourn its loss.

Second, classroom architecture is not some value-free, neutral design. Classroom architecture makes a big difference in how people teach, and how they learn:

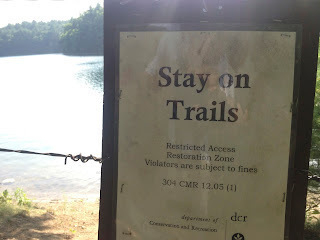

Which is why, as often as I can, I get my students out of the classroom. When we are reading Thoreau's Walking, we go for a walk. When I teach environmental philosophy, we often meet under the great tree in our campus quad, where I encourage students to daydream and to play with the grass, to look for worm-castings and owl pellets, feathers and seed-pods, invertebrates and fallen bits of bark. What good is it to gain the world of theoretical knowledge at the expense of knowledge gained through vital, haptic, bodily experience?

And this is why I am a preacher of the importance of study abroad. Not just travel, but serious, engaged, rigorous study in the classroom of life in another place. This is why I teach Classics in Greece every year, and why year after year I take students to Central America to study environmental philosophy and ecology.

More and more I've been trying to shift the learning focus in my classes from the classroom to the laboratory - where by "laboratory" I mean anywhere that allows students to learn with their whole person. I make my ancient philosophy students devote hours each semester to star-gazing, in part because this is what the ancients did, and in part because I don't want them to miss the stars. I want them to gaze in wonder at the firmament so that when they read Aristotle and Galileo they know that they've looked at what those great minds saw as well. We even occasionally take field trips to really dark places like the South Dakota Badlands so we can see the skies even better.

My environmental philosophy students must observe a square meter of earth for a semester, spending an hour at a time without a camera, drawing and writing about what they see, because it does not make sense to me to talk about the earth when you have not taken the time to sit upon it, to listen to it, to smell and taste it, and to see what other lives creep, and walk, and fly across it.

My friend Aage Jensen advocates the Norwegian philosophy of Friluftsliv, life and education outdoors. And when he organizes a conference on it, he eschews conference centers and holds the conference while walking through the mountains, or paddling a river. Because he believes that one should practice what one preaches, and that nature is always ready to teach.

To paraphrase the Stoic Musonius, teachers would do well to talk less and to take their students with them into the fields, because there they will learn far better and far more than in the lecture hall.

Teaching Outdoors

|

As early as middle school I knew I wanted to become a college professor, and I love my job. It is a delight to spend time with young people who are curious, after all.

Years ago, my friend Matt Dickerson pointed out to me that it's also my job to help those who are not curious to see why they should be. As it turns out, that work is usually delightful, too, a rewarding challenge.

So on the whole, I love my work.

But I admit I don't love classrooms, for several reasons:

First, no matter what decade, every classroom I've been in has exhibited an unhealthy tendency towards becoming cluttered with the latest technology, and most of that tech seems to take up a lot of space and to become the center of attention. I'm not opposed to technology in the classroom, not at all. But I'm opposed to letting it get in the way, as it does when the "Smart Cart" leaves me no room for my lecture notes, or when I can't seem to turn the ceiling-mounted projector on or off. I'm a fan of chalk, because chalk allows spontaneity, and it allows for much more than alphanumeric writing in neat rows. Sadly, concerns about chalk dust getting into computers is threatening to make chalkboards disappear from my classrooms. Alas. Chalk is an excellent technology, and if it vanishes, I will mourn its loss.

Second, classroom architecture is not some value-free, neutral design. Classroom architecture makes a big difference in how people teach, and how they learn:

|

| Step off the trails! Explore! An ironic sign at Walden Pond. |

And this is why I am a preacher of the importance of study abroad. Not just travel, but serious, engaged, rigorous study in the classroom of life in another place. This is why I teach Classics in Greece every year, and why year after year I take students to Central America to study environmental philosophy and ecology.

More and more I've been trying to shift the learning focus in my classes from the classroom to the laboratory - where by "laboratory" I mean anywhere that allows students to learn with their whole person. I make my ancient philosophy students devote hours each semester to star-gazing, in part because this is what the ancients did, and in part because I don't want them to miss the stars. I want them to gaze in wonder at the firmament so that when they read Aristotle and Galileo they know that they've looked at what those great minds saw as well. We even occasionally take field trips to really dark places like the South Dakota Badlands so we can see the skies even better.

My environmental philosophy students must observe a square meter of earth for a semester, spending an hour at a time without a camera, drawing and writing about what they see, because it does not make sense to me to talk about the earth when you have not taken the time to sit upon it, to listen to it, to smell and taste it, and to see what other lives creep, and walk, and fly across it.

My friend Aage Jensen advocates the Norwegian philosophy of Friluftsliv, life and education outdoors. And when he organizes a conference on it, he eschews conference centers and holds the conference while walking through the mountains, or paddling a river. Because he believes that one should practice what one preaches, and that nature is always ready to teach.

To paraphrase the Stoic Musonius, teachers would do well to talk less and to take their students with them into the fields, because there they will learn far better and far more than in the lecture hall.

|

| Nature is full of things worth seeing. |

∞

Matt and I stand thigh-deep in one of the small streams that

tumble down the eastern slopes of the Green Mountains. Many of those

streams, including this one, have carved steep gorges over the

millennia. As the water falls it strips away the sand and loam, leaving

a course choked with jumbled boulders.

Matt and I stand thigh-deep in one of the small streams that

tumble down the eastern slopes of the Green Mountains. Many of those

streams, including this one, have carved steep gorges over the

millennia. As the water falls it strips away the sand and loam, leaving

a course choked with jumbled boulders.

Every year a few more trees, undercut by the current, tip over into the stream, where they lodge against the boulders and form temporary dams. As the water flows over those dams it digs deep plunge pools, bubbling and swirling for a few feet, then quickly settling into swift, clear, tea-colored glassy pools. The water slows only long enough to catch its breath before it plunges again, stair-stepping down the mountain, moving the mountain itself downstream one grain of sand at a time.

Beside us, logs carpeted in moss play host to uncounted lives of plants and animals. Trees reach their branches down into the cleft cut by the river, searching for sunlight wherever they can in this steep gorge. Small flies whirl restlessly across our vision. Their blue wings and olive bodies seem an unnecessary and extravagant dash of color on something so small, so ephemeral.

Vermont is named for the greenness of its mountains, or les monts verts as the first French settlers called these ancient hills. One of the rivers nearby is called the Lemon Fair, its name preserving the French sounds in misplaced English words. A sweeping glance would call this place green, but it only takes a moment of slowing down to really look before you see all the rainbow represented here.

Much of the color is underwater, on the scales of the fine-featured trout that fin the current before us. The native brook trout are dappled a vermiculated green above, fading to pale bellies below. Their fins are slashed with bright red and white. The rainbow trout, imported from the west coast, iridesce when a beam of sunlight finds its way down through the leaves and the water. The young brown trout - far from their native Europe - shine like salmon. Under the rocks small tan sculpin harvest tiny invertebrate meals.

Gray stones slide slower than glaciers down the bank, moving imperceptibly and irresistibly toward the sea. On the bank, seven tiny mushrooms stand up, no taller than my thumb, their caps bright orange like yearling efts.

It is a perfect day. We are grateful to receive it, grateful to be here, to stand in these waters as their life flows around us.

*****

As I think of standing in the river, I am reminded of this passage from Thoreau:

“Late in the afternoon we passed a man on the shore fishing

with a long birch pole, its silvery bark left on, and a dog at his side, rowing

so near as to agitate his cork with our oars, and drive away luck for a season;

and when we had rowed a mile as straight as an arrow, with our faces turned

toward him, and the bubbles in our wake still visible on the tranquil surface,

there stood the fisher still with his dog, like statues under the other side of

the heavens, the only objects to relieve the eye in the extended meadow; and

there would he stand abiding his luck, till he took his way home through the

fields at evening with his fish. Thus, by one bait or another, Nature

allures inhabitants into all her recesses [….] His fishing was not a sport,

nor solely a means of subsistence, but a sort of solemn sacrament and

withdrawal from the world, just as the aged read their Bibles." H.D. Thoreau, A Week On The Concord And Merrimack Rivers, (New York: Signet, 1961; emphasis mine)

p. 31-32.

Green Mountain Creek

Matt and I stand thigh-deep in one of the small streams that

tumble down the eastern slopes of the Green Mountains. Many of those

streams, including this one, have carved steep gorges over the

millennia. As the water falls it strips away the sand and loam, leaving

a course choked with jumbled boulders.

Matt and I stand thigh-deep in one of the small streams that

tumble down the eastern slopes of the Green Mountains. Many of those

streams, including this one, have carved steep gorges over the

millennia. As the water falls it strips away the sand and loam, leaving

a course choked with jumbled boulders.Every year a few more trees, undercut by the current, tip over into the stream, where they lodge against the boulders and form temporary dams. As the water flows over those dams it digs deep plunge pools, bubbling and swirling for a few feet, then quickly settling into swift, clear, tea-colored glassy pools. The water slows only long enough to catch its breath before it plunges again, stair-stepping down the mountain, moving the mountain itself downstream one grain of sand at a time.

Beside us, logs carpeted in moss play host to uncounted lives of plants and animals. Trees reach their branches down into the cleft cut by the river, searching for sunlight wherever they can in this steep gorge. Small flies whirl restlessly across our vision. Their blue wings and olive bodies seem an unnecessary and extravagant dash of color on something so small, so ephemeral.

Vermont is named for the greenness of its mountains, or les monts verts as the first French settlers called these ancient hills. One of the rivers nearby is called the Lemon Fair, its name preserving the French sounds in misplaced English words. A sweeping glance would call this place green, but it only takes a moment of slowing down to really look before you see all the rainbow represented here.

Much of the color is underwater, on the scales of the fine-featured trout that fin the current before us. The native brook trout are dappled a vermiculated green above, fading to pale bellies below. Their fins are slashed with bright red and white. The rainbow trout, imported from the west coast, iridesce when a beam of sunlight finds its way down through the leaves and the water. The young brown trout - far from their native Europe - shine like salmon. Under the rocks small tan sculpin harvest tiny invertebrate meals.

Gray stones slide slower than glaciers down the bank, moving imperceptibly and irresistibly toward the sea. On the bank, seven tiny mushrooms stand up, no taller than my thumb, their caps bright orange like yearling efts.

It is a perfect day. We are grateful to receive it, grateful to be here, to stand in these waters as their life flows around us.

*****

|

| My friends Bill and Brian paddle the Concord River, as Thoreau once did. |

*****

*****

Note: I think Matt intended his gesture of catching water in fun, but I like

the way it looks like a gesture of gratefully receiving the waterfall.

I'm also reminded of a sentence I recently read in Stephanie Mills' book, Epicurean Simplicity:

“[F]ishers can be natural historians and waterside contemplatives par excellence."

By “fishers” she means those who fish,

fishermen and fisherwomen and fisherchildren. This comes at the conclusion of a story in which she almost

reprimanded a small boy who was catching fish for bait, but then decided not to

do so. She was afraid he was catching too many, or juvenile fish that would not grow to maturity. Later, she considered the

fact that if he was fishing, he could well be learning about fish in a way no

one else does. She reports that she was glad she didn't reprimand him.

It's true that in hunting and fishing some people learn practices of cruelty towards animals, or learn to regard animals instrumentally; but my experience is that most of the people I know who hunt and fish know a lot more about nature than the average person who does not. Harvesting wild food often makes people naturalists, and can indeed make us much more "mindful carnivores" as Tovar Cerulli puts it.

Anecdotally, I find that hunting and fishing have made me less of a carnivore, and increasingly concerned with animal flourishing. (The quote from Stephanie Mills is found in Epicurean Simplicity, published in Washington, Covelo, and London: Island Press/Shearwater Books, 2002 p.125.)

*****

∞

When I was preparing to go to grad school I was torn between two choices: Ph.D. in marine/riparian biology, or Ph.D. in philosophy? I love fish, aquatic invertebrates,

(well, most of them, anyway) and the environments they live in. Wouldn't it be great to make freestone streams and tidal pools into my classrooms?

But I also love philosophy. Philosophy has connections to every other discipline; it offers a unique perspective on human activities; and it promotes some of the most interesting and fruitful conversations I know of. (Yes, I admit some professional bias here, and don't begrudge others a similar bias towards what they love.) Philosophy classes take on questions about truth, value, meaning, religion, justice, science, language, reason, history, relationships, and much more. It can be very difficult, but there's usually a huge payoff for the effort you put into it.

Now that I teach philosophy, I often find myself lurking around the biology department at my school, to read their journals, to talk with the professors there (who patiently put up with my presence there), and to eye their labs with envy.

Now, I think bio labs are great places, but it's not the places themselves that I most like. It's rather the idea of the place. Labs are spaces set apart for learning by experience. We have labs for the sciences, and we have labs for the arts as well (though we usually call those "studios"). In the social sciences they use labs for observing human activities, and foreign languages have (or ought to have) labs for practicing language. Writers have workshops, historians have museums and archives, and other disciplines have internships.

Philosophy, unlike all these other disciplines, does not appear to have any labs at all. At least, not at first glance.

Partly this is due to the reflective nature of philosophy: philosophers have often understood our discipline as a step back from experience in order to gain a cool, disinterested view of the world. To some degree, we still think that, but that idea of having a privileged access to reality through the use of the right kind of language, or through a scientific worldview, has fallen under suspicion. Pace Descartes, we don't necessarily understand the world better by turning completely away from it.

Contrary to popular opinion, "philosophy" is not a synonym for "opinion." Nor is it a synonym for "doctrines." Philosophy has grown and changed quite a lot in the last few centuries, which means that is not always easy to define. One thing that is common to all philosophers, however, is that philosophy is an activity. Doing philosophy is not the mere rehearsal of past views, nor is it merely an attempt to present our already established opinions in clearer or more persuasive language.

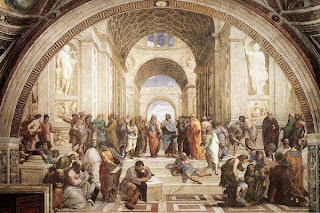

Philosophers do, in fact, set aside spaces and times for practicing philosophy. One important kind of lab philosophers have is the seminar, which has its roots in Plato's practice of philosophy. Whatever else we might say about Plato, he knew how important good conversation is to advancing philosophy. In his dialogues, Plato uses conversation to illustrate two points: first, we need to spend at least some of our time in serious, sustained conversation and reflection with others. Second, when we do so, we need to follow the argument where it leads and not just where we want it to go.

In future posts I'll take up several other kinds of "labs" philosophers use, which I'll mention briefly here. First, recently, some philosophers have begun doing what they call "experimental philosophy." Second, I find that teaching philosophy "in the field" (for environmental philosophy or ethics, for instance) or teaching abroad provides a special experience for animating philosophical conversations. Third, I've come up with several "hands-on" (or, just as often, "eyes-on") projects for my classes in Ancient and Medieval Philosophy and Environmental Philosophy that are helpful pedagogical tools.

*********************

[Images: Raphael's "School of Athens," showing famous Greek philosophers "at work"; two mayflies photgraphed in the summer of 2009 in Gravenhurst, Ontario; one of the tributaries to Lake Muskoka in Ontario; a brook trout photographed on the Magalloway River in Maine, 2009 while fishing and doing some research with Matt Dickerson. The Raphael image is in the public domain; the others are my own photos. I think mayflies are especially lovely creatures. The adult stage shown above is a very brief period of their lives; most of their lives are spent underwater, and their appearance is quite different then from what it is as adults.]

Do Philosophy Classes Have "Labs"?

When I was preparing to go to grad school I was torn between two choices: Ph.D. in marine/riparian biology, or Ph.D. in philosophy? I love fish, aquatic invertebrates,

(well, most of them, anyway) and the environments they live in. Wouldn't it be great to make freestone streams and tidal pools into my classrooms?

But I also love philosophy. Philosophy has connections to every other discipline; it offers a unique perspective on human activities; and it promotes some of the most interesting and fruitful conversations I know of. (Yes, I admit some professional bias here, and don't begrudge others a similar bias towards what they love.) Philosophy classes take on questions about truth, value, meaning, religion, justice, science, language, reason, history, relationships, and much more. It can be very difficult, but there's usually a huge payoff for the effort you put into it.

Now that I teach philosophy, I often find myself lurking around the biology department at my school, to read their journals, to talk with the professors there (who patiently put up with my presence there), and to eye their labs with envy.

Now, I think bio labs are great places, but it's not the places themselves that I most like. It's rather the idea of the place. Labs are spaces set apart for learning by experience. We have labs for the sciences, and we have labs for the arts as well (though we usually call those "studios"). In the social sciences they use labs for observing human activities, and foreign languages have (or ought to have) labs for practicing language. Writers have workshops, historians have museums and archives, and other disciplines have internships.

Philosophy, unlike all these other disciplines, does not appear to have any labs at all. At least, not at first glance.

Partly this is due to the reflective nature of philosophy: philosophers have often understood our discipline as a step back from experience in order to gain a cool, disinterested view of the world. To some degree, we still think that, but that idea of having a privileged access to reality through the use of the right kind of language, or through a scientific worldview, has fallen under suspicion. Pace Descartes, we don't necessarily understand the world better by turning completely away from it.

Contrary to popular opinion, "philosophy" is not a synonym for "opinion." Nor is it a synonym for "doctrines." Philosophy has grown and changed quite a lot in the last few centuries, which means that is not always easy to define. One thing that is common to all philosophers, however, is that philosophy is an activity. Doing philosophy is not the mere rehearsal of past views, nor is it merely an attempt to present our already established opinions in clearer or more persuasive language.

Philosophers do, in fact, set aside spaces and times for practicing philosophy. One important kind of lab philosophers have is the seminar, which has its roots in Plato's practice of philosophy. Whatever else we might say about Plato, he knew how important good conversation is to advancing philosophy. In his dialogues, Plato uses conversation to illustrate two points: first, we need to spend at least some of our time in serious, sustained conversation and reflection with others. Second, when we do so, we need to follow the argument where it leads and not just where we want it to go.

|

| A brook trout I photographed in Maine. |

*********************

[Images: Raphael's "School of Athens," showing famous Greek philosophers "at work"; two mayflies photgraphed in the summer of 2009 in Gravenhurst, Ontario; one of the tributaries to Lake Muskoka in Ontario; a brook trout photographed on the Magalloway River in Maine, 2009 while fishing and doing some research with Matt Dickerson. The Raphael image is in the public domain; the others are my own photos. I think mayflies are especially lovely creatures. The adult stage shown above is a very brief period of their lives; most of their lives are spent underwater, and their appearance is quite different then from what it is as adults.]