memory

∞

Not The Weapons But What They Defend

My latest post at Sojourners' "God's Politics" blog:

"My grandfather was a career military officer, and I admired him deeply for it. As a child, I would try to imagine the battles he was in, and I thought of him as a hero. As I grew older, I became more aware of what he had given up for us, and what that might have cost him...."Read it all here.

∞

Hid In My Heart

Before my friend's father died, he had a stroke that left him mostly without words for a few weeks. His near-total aphasia left little intact, but there were some words that came out readily. My friend's dad had been a pastor, and when his faculty of speech left him, the words of his prayers, of the scriptures, and of the hymns and psalms were all that remained. Daily habit of repetition had ingrained them in his heart, too deep to be erased by the stroke.

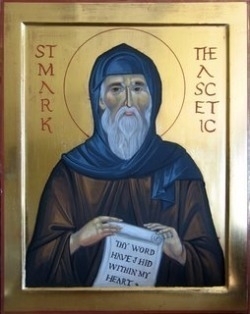

On his blog, Kelly Dean Jolley has an icon of St Mark the Ascetic, or St Mark the Wrestler, that Jolley has kindly allowed me to include here. In his hands St Mark holds a scroll that reads "Thy word have I hid within my heart." Those words are from the 119th Psalm, a long poem about scripture.

When I was in college, my French professor Charles Nunley required me to memorize a new poem every week. Every week or two I'd go to his office and he would name one of the poems I'd learned and expect me to recite it, and then to discuss it. I'm not a great memorizer, so it was painful work, but I've been grateful for the discipline every year since then. It is a gift to have verses hidden in my heart.

When I was in college, my French professor Charles Nunley required me to memorize a new poem every week. Every week or two I'd go to his office and he would name one of the poems I'd learned and expect me to recite it, and then to discuss it. I'm not a great memorizer, so it was painful work, but I've been grateful for the discipline every year since then. It is a gift to have verses hidden in my heart.

I am reminded of Mary, the mother of Jesus, when she heard what the shepherds were saying. Luke tells us that she "treasured these things in her heart," which I take to mean that she heard them, and then put them in that front room of her memory, the palm and fingertips of the mind where we touch and explore and consider ideas, turning them over and over again.

Well, this is what I do with treasured verses, anyway. Like I said, I'm a poor memorizer. But when I work at it, I hold the verses at mind's-eye level and gaze at them, running my inner eye down the length of them repeatedly, considering the way the grain moves and feeling the heft of the words until the grooves of my mind fit the notches of the words like a key. Because I hope that what I have hid in my heart will be like the Brothers Grimm's "Golden Key," which opens...well, I had better not tell you. Read it for yourself.

I wonder - when the great grinding erasure of time scrubs away at my memories, what will be left? What grooves in my grain will be too deep to scrape away? What treasures, what verses, what songs of my species will be buried too deep in my heart for the thief of time to steal?

On his blog, Kelly Dean Jolley has an icon of St Mark the Ascetic, or St Mark the Wrestler, that Jolley has kindly allowed me to include here. In his hands St Mark holds a scroll that reads "Thy word have I hid within my heart." Those words are from the 119th Psalm, a long poem about scripture.

When I was in college, my French professor Charles Nunley required me to memorize a new poem every week. Every week or two I'd go to his office and he would name one of the poems I'd learned and expect me to recite it, and then to discuss it. I'm not a great memorizer, so it was painful work, but I've been grateful for the discipline every year since then. It is a gift to have verses hidden in my heart.

When I was in college, my French professor Charles Nunley required me to memorize a new poem every week. Every week or two I'd go to his office and he would name one of the poems I'd learned and expect me to recite it, and then to discuss it. I'm not a great memorizer, so it was painful work, but I've been grateful for the discipline every year since then. It is a gift to have verses hidden in my heart.I am reminded of Mary, the mother of Jesus, when she heard what the shepherds were saying. Luke tells us that she "treasured these things in her heart," which I take to mean that she heard them, and then put them in that front room of her memory, the palm and fingertips of the mind where we touch and explore and consider ideas, turning them over and over again.

Well, this is what I do with treasured verses, anyway. Like I said, I'm a poor memorizer. But when I work at it, I hold the verses at mind's-eye level and gaze at them, running my inner eye down the length of them repeatedly, considering the way the grain moves and feeling the heft of the words until the grooves of my mind fit the notches of the words like a key. Because I hope that what I have hid in my heart will be like the Brothers Grimm's "Golden Key," which opens...well, I had better not tell you. Read it for yourself.

I wonder - when the great grinding erasure of time scrubs away at my memories, what will be left? What grooves in my grain will be too deep to scrape away? What treasures, what verses, what songs of my species will be buried too deep in my heart for the thief of time to steal?

∞

Have We Met?

This weekend I found myself standing next to an older woman I've met a number of times before. For a moment, I struggled to remember where we'd met, then it hit me: she has taken a few of the classes I've offered for senior citizens from time to time. As I recall, she's always been a great student, though I confess I'm having trouble remembering her name right now, and feeling a little sheepish about my memory.

As it turns out, she has it even worse. When I greeted her, she asked me with her usual winning smile, "Have we met?" I told her we had, and where we had met. She said she had no recollection, and I thought she must be joking. Then she added that she has recently suffered a head injury and has lost her memory. She remembers that she once had such a powerful memory she was reluctant to tell people how much she remembered, lest she appear to be boasting.

Now she has very little of that memory left. She was cheerful, as always, but I thought maybe a little sad at what she had lost.

A little earlier in the day I had been speaking about C.S. Lewis and ecology to a church group. There I spent some time reflecting on a passage in Lewis's novel Out Of The Silent Planet where Hyoi cannot understand Ransom's culture. What kind of people would insist on having a pleasant experience again and again, Hyoi asks. Isn't that like wanting to hear a single word from a beautiful poem over and over, but not the whole poem? Isn't memory a part of the pleasure?

I have often taken comfort from that passage, since Hyoi's position is that growing old is not a loss but a gain, just as it is a gain to listen to a full symphony and not just the overture. Perhaps this is why we fear losing our memories: as the symphony of life approaches the finale sometimes we forget the overture.

As my former student turned to go, I told her "It's nice to meet you - again." She smiled, and walked away.

As it turns out, she has it even worse. When I greeted her, she asked me with her usual winning smile, "Have we met?" I told her we had, and where we had met. She said she had no recollection, and I thought she must be joking. Then she added that she has recently suffered a head injury and has lost her memory. She remembers that she once had such a powerful memory she was reluctant to tell people how much she remembered, lest she appear to be boasting.

Now she has very little of that memory left. She was cheerful, as always, but I thought maybe a little sad at what she had lost.

A little earlier in the day I had been speaking about C.S. Lewis and ecology to a church group. There I spent some time reflecting on a passage in Lewis's novel Out Of The Silent Planet where Hyoi cannot understand Ransom's culture. What kind of people would insist on having a pleasant experience again and again, Hyoi asks. Isn't that like wanting to hear a single word from a beautiful poem over and over, but not the whole poem? Isn't memory a part of the pleasure?

I have often taken comfort from that passage, since Hyoi's position is that growing old is not a loss but a gain, just as it is a gain to listen to a full symphony and not just the overture. Perhaps this is why we fear losing our memories: as the symphony of life approaches the finale sometimes we forget the overture.

As my former student turned to go, I told her "It's nice to meet you - again." She smiled, and walked away.

∞

Writing, Law, and Memory in Ancient Gortyn

In the ruins of Gortyn, in central Crete, some of the famous ancient laws of Crete are preserved in stone. Archaeologists uncovered them in 1884, and have since built a brick enclosure to protect them from the weather.

Even though I'm not an expert in the Doric dialect, I love to read this inscription, for several reasons that might interest even those who don't know Greek.

First of all, it has an unusual alphabet, containing fewer letters than modern or classical Attic Greek. It lacks the vowels eta and omega (for which it uses epsilon and omicron), and the consonants zeta, xi, phi, chi, and psi (for which it substitutes other letters or combinations of other letters: two deltas for zeta, kappa+sigma for xi; pi for phi; kappa for chi; pi+sigma for psi.)

It also uses a letter that has since fallen out of use, the digamma. The digamma (or wau) is probably related to the Hebrew letter waw (or vav) and to the Roman letter F, which it closely resembles. By the classical age it had dropped out of use in Greek, and is fairly rare, like the letters sampi and qoppa.

(There is also a digamma in Delphi, not far from the Athena Pronaia sanctuary, on an upright stone dedicated to Athenai Warganai. That second word is related to the Greek word for "work" or "deed," ergon, and also to our word "work." This stone, pictured below, evinces several peculiarities of archaic Greek script. Look at the second word, which looks like it says FARCANAI. The first letter is digamma; the third letter, rho, very much resembles the Latin "R"; the letter immediately after it, gamma, looks like a flattened upper-case "C.")

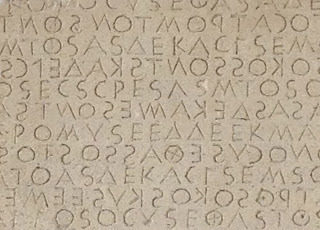

Second, the writing is in boustrophedon style. Boustrophedon means something like "as the ox turns." Today we write in stoichedon style, in which all the letters face the same direction, like soldiers standing in formation. Boustrophedon is based on an agricultural, not a military ideal: the writer writes as a farmer plows. Write to the end of the line, and then, rather than returning to the left side of the page, turn the letters to face the opposite direction and write from right to left. When you read boustrophedon, your eye follows a zig-zag across the page -- or the stone.

Have a look at this close-up of the engraving at Gortys and look at the way letters like "E," "K," and "S" face in adjacent lines:

(By the way, that "S" character is actually an iota; sigmas look like this: M; mu is like our "M" with an extra stroke added.)

There are a lot of other reasons to like this place, and this inscription, but I'll limit myself to just one more thing for now: memory.

This inscription is one way that an ancient community deliberately remembered their laws. They wrote down what they decided, and that has affected our lives. Writing the law down makes it accessible to everyone, and makes judicial decisions transparent. It establishes a set of expectations for conduct in the community, and makes those expectations known even to aliens.

The code at Gortyn records (in Column IX, around the middle, if you're curious) the presence at court of someone in addition to the judge: the mnemon. You can see by the word's resemblance to our word "mnemonic" that it has to do with memory. The mnemon's job was to act as a witness to previous judicial decisions, and to remember them and remind the judge of those decisions. The mnemon's job was not to decide cases but to be a kind of embodiment of the law and therefore an embodiment of fairness.

Unfortunately, no mnemon lives forever. Presumably, the writing on the wall at Gortyn was a way of preserving what mattered most in the court, so that when they passed away, their memories would live on through the ages.

*****

Harold Fowler writes in a footnote to his 1921 translation of the Cratylus that under Eucleides the Athenians officially changed their alphabet from the archaic one to the Ionian alphabet in 404/403 BCE. This expanded their system of vowels, adding the long vowels eta and omega. It became known as the Euclidean Alphabet.

*****

If you can find it, Adonis Vasilakis' The Great Inscription of the Law Code of Gortyn (Heraklion/Iraklio: Mystis O.E.) is a great resource. It has a facsimile of the whole wall, a complete translation, and some helpful historical observations. ISBN 9608853400

|

| Gortyn, Crete |

Even though I'm not an expert in the Doric dialect, I love to read this inscription, for several reasons that might interest even those who don't know Greek.

First of all, it has an unusual alphabet, containing fewer letters than modern or classical Attic Greek. It lacks the vowels eta and omega (for which it uses epsilon and omicron), and the consonants zeta, xi, phi, chi, and psi (for which it substitutes other letters or combinations of other letters: two deltas for zeta, kappa+sigma for xi; pi for phi; kappa for chi; pi+sigma for psi.)

It also uses a letter that has since fallen out of use, the digamma. The digamma (or wau) is probably related to the Hebrew letter waw (or vav) and to the Roman letter F, which it closely resembles. By the classical age it had dropped out of use in Greek, and is fairly rare, like the letters sampi and qoppa.

(There is also a digamma in Delphi, not far from the Athena Pronaia sanctuary, on an upright stone dedicated to Athenai Warganai. That second word is related to the Greek word for "work" or "deed," ergon, and also to our word "work." This stone, pictured below, evinces several peculiarities of archaic Greek script. Look at the second word, which looks like it says FARCANAI. The first letter is digamma; the third letter, rho, very much resembles the Latin "R"; the letter immediately after it, gamma, looks like a flattened upper-case "C.")

|

|

"Athenai Warganai" inscription at Delphi

|

Second, the writing is in boustrophedon style. Boustrophedon means something like "as the ox turns." Today we write in stoichedon style, in which all the letters face the same direction, like soldiers standing in formation. Boustrophedon is based on an agricultural, not a military ideal: the writer writes as a farmer plows. Write to the end of the line, and then, rather than returning to the left side of the page, turn the letters to face the opposite direction and write from right to left. When you read boustrophedon, your eye follows a zig-zag across the page -- or the stone.

Have a look at this close-up of the engraving at Gortys and look at the way letters like "E," "K," and "S" face in adjacent lines:

|

| Close-up of the Gortyn Code |

There are a lot of other reasons to like this place, and this inscription, but I'll limit myself to just one more thing for now: memory.

This inscription is one way that an ancient community deliberately remembered their laws. They wrote down what they decided, and that has affected our lives. Writing the law down makes it accessible to everyone, and makes judicial decisions transparent. It establishes a set of expectations for conduct in the community, and makes those expectations known even to aliens.

The code at Gortyn records (in Column IX, around the middle, if you're curious) the presence at court of someone in addition to the judge: the mnemon. You can see by the word's resemblance to our word "mnemonic" that it has to do with memory. The mnemon's job was to act as a witness to previous judicial decisions, and to remember them and remind the judge of those decisions. The mnemon's job was not to decide cases but to be a kind of embodiment of the law and therefore an embodiment of fairness.

Unfortunately, no mnemon lives forever. Presumably, the writing on the wall at Gortyn was a way of preserving what mattered most in the court, so that when they passed away, their memories would live on through the ages.

|

| National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Possibly a child's dish? The sixth letter is digamma. |

*****

Harold Fowler writes in a footnote to his 1921 translation of the Cratylus that under Eucleides the Athenians officially changed their alphabet from the archaic one to the Ionian alphabet in 404/403 BCE. This expanded their system of vowels, adding the long vowels eta and omega. It became known as the Euclidean Alphabet.

*****

If you can find it, Adonis Vasilakis' The Great Inscription of the Law Code of Gortyn (Heraklion/Iraklio: Mystis O.E.) is a great resource. It has a facsimile of the whole wall, a complete translation, and some helpful historical observations. ISBN 9608853400