mourning

∞

Light Perpetual

My friend Michael Foster died last night.

We knew it was coming. We saw it a long way off.

It still hurts like hell.

That's what this bereavement feels like: a little piece of hell. Our word "bereave" shares roots with "robbery," "rupture," and "interrupt." Something has been stolen from us, something has been broken, broken off. It should not be this way.

The words of Mark Heard's song "Treasure of the Broken Land" are going through my mind again and again:

The realization that he is gone keeps hitting me in waves. Now, as I write this, I keep having to stop as my throat constricts and my heart pounds, waiting for the tremor to pass through me, waiting for this wave of anguish to roll over me.

Maybe telling some of his story - our story - will help.

I met Mike when I was a grad student at Penn State. He was a professor at Penn State, and a sub-deacon at our church. (This means he helped with bread and wine, and looked good in a dress.) We both attended St Andrew's Episcopal Church in State College, and together we served on the vestry.

Sometime in my last year or two of grad work - I don't remember exactly; odd how the most important things can seem so commonplace - he invited me to go out to breakfast at the Corner Room. Like so many other kind professors I knew, he insisted on paying. (I now do the same with my students; the little things that mark our lives often become the lessons we really teach.)

Mike was trying to live the best life he could, using his scholarly discipline to love his neighbor, and trying to love his God to the best of his ability. He'd begun reading Dallas Willard's book The Divine Conspiracy, a book about becoming an intentional follower of Christ. I knew Willard's work on Husserl, and I guess Mike figured that made me a good conversation partner. We started meeting every week; he'd buy me breakfast and we'd talk about another chapter of Willard's book.

I didn't know what to make of Willard, and I was reading a lot of other books (this is the life of a grad student, after all) so the book didn't sink in much. But Mike's life did. Mostly we let the book lead us to talking about how we were living, and why we did what we did. Mike had studied economics, and recently his work had become really important to him as he discovered how to combine the methods of his discipline and of developmental psychology to advocate for poor children. His field was not mine, but I gathered that this was the upshot: a little money invested in children will pay dividends in their lives forever.

Mike was a restless soul, like Augustine, only finding his rest in God. I've lost count of how many times he and Mary and their four kids moved, but I know we've visited them in North Carolina and Alabama since we all left Pennsylvania. He wasn't afraid to pull up his stakes and move somewhere else if he thought he could do better work there. He has urged me, several times, to do the same, to be willing to regard tenure as a shackle rather than a privilege, and to move where the spirit moves me.

A few years ago Mike was diagnosed with a tumor in his brain. He approached this with the same doggedness he approached everything else. He poured himself into researching treatments, and flew all over the country seeking good medical advice. The tumor was removed at the cost of one of his eyes, and he went through some grueling radiation. (I long for the day when we will look back on our modern cancer treatments the way we now look back on bloodletting.) A little over a year ago he was at Mayo, not too far from me. I drove over to see him and Mary, and they gave me the gift of letting me pray for them. I say this is a gift, because I am at best a fumbling prayer, and they made me feel like a priest. They were suffering, and here they were, giving me this gift of unmerited affirmation.

Last summer a friend from Australia passed through Sioux Falls while enjoying a long service leave. He had rented a car and was driving from Seattle to Birmingham. I took advantage of my sabbatical and hopped in the car with him so I could visit Mike and Mary. They'd just moved to a new home, everything was in boxes, Mike's tumor was growing again, and yet they took me in and made me feel like I was long-lost family recently found again.

I loved talking with Mike, because his offhand observations were like gold. And the way he talked to people, and treated people, were always examples of both wit and grace. He was kind, and that allowed him to talk straight, to say with smiling integrity and southern charm, exactly what he was thinking. He was a true Israelite, in whom there wasn't much guile, and the guile that was there made him fun, and good company. I loved the way he loved his wife, and his kids. He wore that on the outside, not for show, but because his love was too big to keep on the inside. I'm sure it was flawed, as all loves are, but it was also intentional, the centerpiece of his life.

A couple of months ago, Mike asked if we could talk. You never know when the conversation you have will be the last one you ever have; this was ours. He told me the doctor had bad news: he might make it to Christmas, but not likely past that.

Mike asked me if he had lived right, if he had done the right thing. Yes, oh yes, Mike. I don't see as God sees, but I don't see how God could say otherwise. You made my life better. You loved well, in everything you did.

He also asked me if it was okay to ask God for healing. This one was harder to answer, but I decided that after thirteen years of benefiting from his straight talk, from free breakfasts and warm hospitality, I owed him nothing less than that. "It's okay to ask, Mike," I hesitated, not wanting to say it, not wanting to believe what would come next. I could hear in his conversation that he was declining, that his memory was being eaten away by the tumor. "But God's not required to answer those prayers. Miracles happen, but we call them miracles because they're rare. Christ died, and you and I will die too. It's time to start thinking about passing your work on to others."

His work was so good, too. He was at a new hinge-point, a pivot on which his research was ready to swing hard at injustice. He could see how ten more years of work - even two more years of work - would make a big difference. "I've got so much more to do; why is God taking me away now?" he asked. "I don't know, Mike. I just don't know."

Once again, as his last gift to me, he asked me to pray for him. It was hard to find the words, but I tried to talk to God the way Mike talked to me, letting Mike's life be a lesson in prayer. I don't like what you're doing, God. Make it better, make it right.

I suppose it is better for Mike not to be suffering, but Mike's death doesn't seem better, or right to me. I want him back, God. I know I can't have him back, not yet, but I miss him and it hurts.

If I cannot have him back, then give us this: a double portion of his spirit. The world is darker without him. I cannot see for the tears in my eyes; I cannot hear his voice anymore. I don't know how to pray. Give me his courage, and his wisdom, and his love. Let him be enshrined in me. Let all that was good in him live in my life now, and in the lives of his wife, his children, his students. Oh, this is the hard thing to ask: let us continue his work, with his spirit.

Mark Heard's words give me some hope:

Update: If you'd like to attend the memorial service on Wednesday, May 22, you may find details here. Mike asked that we wear bright colors, not black, to celebrate his life and to maintain our hope for the future.

We knew it was coming. We saw it a long way off.

It still hurts like hell.

That's what this bereavement feels like: a little piece of hell. Our word "bereave" shares roots with "robbery," "rupture," and "interrupt." Something has been stolen from us, something has been broken, broken off. It should not be this way.

The words of Mark Heard's song "Treasure of the Broken Land" are going through my mind again and again:

I thought our days were commonplaceI knew our days didn't number in the millions, but that's what my heart longed for, Mike. The loss hurts like hell because the time spent with you felt like heaven, like something that was meant to be eternal.

I thought they numbered in the millions

Now there's only the aftertaste

Of circumstance that can't pass this way again.

The realization that he is gone keeps hitting me in waves. Now, as I write this, I keep having to stop as my throat constricts and my heart pounds, waiting for the tremor to pass through me, waiting for this wave of anguish to roll over me.

Maybe telling some of his story - our story - will help.

I met Mike when I was a grad student at Penn State. He was a professor at Penn State, and a sub-deacon at our church. (This means he helped with bread and wine, and looked good in a dress.) We both attended St Andrew's Episcopal Church in State College, and together we served on the vestry.

Sometime in my last year or two of grad work - I don't remember exactly; odd how the most important things can seem so commonplace - he invited me to go out to breakfast at the Corner Room. Like so many other kind professors I knew, he insisted on paying. (I now do the same with my students; the little things that mark our lives often become the lessons we really teach.)

Mike was trying to live the best life he could, using his scholarly discipline to love his neighbor, and trying to love his God to the best of his ability. He'd begun reading Dallas Willard's book The Divine Conspiracy, a book about becoming an intentional follower of Christ. I knew Willard's work on Husserl, and I guess Mike figured that made me a good conversation partner. We started meeting every week; he'd buy me breakfast and we'd talk about another chapter of Willard's book.

I didn't know what to make of Willard, and I was reading a lot of other books (this is the life of a grad student, after all) so the book didn't sink in much. But Mike's life did. Mostly we let the book lead us to talking about how we were living, and why we did what we did. Mike had studied economics, and recently his work had become really important to him as he discovered how to combine the methods of his discipline and of developmental psychology to advocate for poor children. His field was not mine, but I gathered that this was the upshot: a little money invested in children will pay dividends in their lives forever.

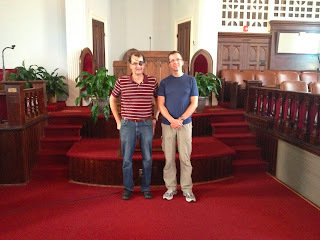

|

| Mike and I stand together in the Dexter Ave King Memorial Church |

A few years ago Mike was diagnosed with a tumor in his brain. He approached this with the same doggedness he approached everything else. He poured himself into researching treatments, and flew all over the country seeking good medical advice. The tumor was removed at the cost of one of his eyes, and he went through some grueling radiation. (I long for the day when we will look back on our modern cancer treatments the way we now look back on bloodletting.) A little over a year ago he was at Mayo, not too far from me. I drove over to see him and Mary, and they gave me the gift of letting me pray for them. I say this is a gift, because I am at best a fumbling prayer, and they made me feel like a priest. They were suffering, and here they were, giving me this gift of unmerited affirmation.

Last summer a friend from Australia passed through Sioux Falls while enjoying a long service leave. He had rented a car and was driving from Seattle to Birmingham. I took advantage of my sabbatical and hopped in the car with him so I could visit Mike and Mary. They'd just moved to a new home, everything was in boxes, Mike's tumor was growing again, and yet they took me in and made me feel like I was long-lost family recently found again.

I loved talking with Mike, because his offhand observations were like gold. And the way he talked to people, and treated people, were always examples of both wit and grace. He was kind, and that allowed him to talk straight, to say with smiling integrity and southern charm, exactly what he was thinking. He was a true Israelite, in whom there wasn't much guile, and the guile that was there made him fun, and good company. I loved the way he loved his wife, and his kids. He wore that on the outside, not for show, but because his love was too big to keep on the inside. I'm sure it was flawed, as all loves are, but it was also intentional, the centerpiece of his life.

A couple of months ago, Mike asked if we could talk. You never know when the conversation you have will be the last one you ever have; this was ours. He told me the doctor had bad news: he might make it to Christmas, but not likely past that.

Mike asked me if he had lived right, if he had done the right thing. Yes, oh yes, Mike. I don't see as God sees, but I don't see how God could say otherwise. You made my life better. You loved well, in everything you did.

He also asked me if it was okay to ask God for healing. This one was harder to answer, but I decided that after thirteen years of benefiting from his straight talk, from free breakfasts and warm hospitality, I owed him nothing less than that. "It's okay to ask, Mike," I hesitated, not wanting to say it, not wanting to believe what would come next. I could hear in his conversation that he was declining, that his memory was being eaten away by the tumor. "But God's not required to answer those prayers. Miracles happen, but we call them miracles because they're rare. Christ died, and you and I will die too. It's time to start thinking about passing your work on to others."

His work was so good, too. He was at a new hinge-point, a pivot on which his research was ready to swing hard at injustice. He could see how ten more years of work - even two more years of work - would make a big difference. "I've got so much more to do; why is God taking me away now?" he asked. "I don't know, Mike. I just don't know."

Once again, as his last gift to me, he asked me to pray for him. It was hard to find the words, but I tried to talk to God the way Mike talked to me, letting Mike's life be a lesson in prayer. I don't like what you're doing, God. Make it better, make it right.

I suppose it is better for Mike not to be suffering, but Mike's death doesn't seem better, or right to me. I want him back, God. I know I can't have him back, not yet, but I miss him and it hurts.

If I cannot have him back, then give us this: a double portion of his spirit. The world is darker without him. I cannot see for the tears in my eyes; I cannot hear his voice anymore. I don't know how to pray. Give me his courage, and his wisdom, and his love. Let him be enshrined in me. Let all that was good in him live in my life now, and in the lives of his wife, his children, his students. Oh, this is the hard thing to ask: let us continue his work, with his spirit.

Mark Heard's words give me some hope:

I see you now and then in dreamsMay light perpetual shine upon you, Mike. May I see you, and hear you, in my dreams. May the light of Christ that shone in you while you were awake now shine in us while you sleep. And may we all awake to the same dawn, soon.

Your voice sounds like it used to

I believe I will hear it again

God, how I love you!

*****

Update: If you'd like to attend the memorial service on Wednesday, May 22, you may find details here. Mike asked that we wear bright colors, not black, to celebrate his life and to maintain our hope for the future.

∞

The Pastoral And The Personal In Theodicy

Theodicies, like some virtue ethics and certain ontological arguments, are easy targets for refutation, but much depends on the way they are used.

A theodicy is an attempt to reconcile the apparent evil in the world with the alleged goodness of God, often by showing that the very goodness of God makes some evil necessary; or by arguing that the goodness of God is amplified by a certain amount of evil. In other words, the evil we experience and witness is, in the end, made to serve goodness.

When theodicies are spoken publicly and authoritatively, there is a real danger that they will be used to justify further evil. If evil serves good, and evil is easier to accomplish directly than goodness, why not practice evil?

There's also the very real danger that theodicies will isolate us from one another. Sometimes some perversity in us makes us inclined to tell someone who is experiencing fresh grief that "it's all for the good," or "it will all work out well in the end," or "your loved one is now in a better place." I would guess we do this because we do not know what else to say, and because we want the discomfort of grief banished from our presence. In which case we speak those words like an incantation, using magic to make the unpleasantness disappear. But the grief is not detachable from the griever, so to will the banishment of the mourning is to will the death of the mourner. In simpler terms, when we invoke thoughtless theodicies, sometimes we are committing human sacrifice - throwing out the mourner - in order to comfort ourselves.

In spite of this, I think there is still a place for theodicies - just as there is a place for ontological arguments - provided they originate with the believer and are not forced upon her. The mourner who chooses to believe that the dearly departed have gone to well-earned rest may believe that. That belief may be the germination of the seeds of honor and love, or the expression of grief combined with commitment to the flourishing of the memory of the beloved - it may be the fruit of the idea that the cosmos has no right to bring this love to an end. You may destroy the body, but the soul you shall not take from me.

Of course, the mourner's grief should not turn into fixed doctrine for the rest of us, either. Some things we simply don't know. Death is a horizon we pass only once, a boundary that few - if any - signs are allowed to pass over. But precisely because we do not know what comes after - because we do not even know ourselves much of the time - we may allow others what they need to endure their losses, neither forcing our justifications of evil upon them, nor denying them the explanations that may give them the comfort their hearts need.

A theodicy is an attempt to reconcile the apparent evil in the world with the alleged goodness of God, often by showing that the very goodness of God makes some evil necessary; or by arguing that the goodness of God is amplified by a certain amount of evil. In other words, the evil we experience and witness is, in the end, made to serve goodness.

|

| Roman tombs in southern Crete. |

There's also the very real danger that theodicies will isolate us from one another. Sometimes some perversity in us makes us inclined to tell someone who is experiencing fresh grief that "it's all for the good," or "it will all work out well in the end," or "your loved one is now in a better place." I would guess we do this because we do not know what else to say, and because we want the discomfort of grief banished from our presence. In which case we speak those words like an incantation, using magic to make the unpleasantness disappear. But the grief is not detachable from the griever, so to will the banishment of the mourning is to will the death of the mourner. In simpler terms, when we invoke thoughtless theodicies, sometimes we are committing human sacrifice - throwing out the mourner - in order to comfort ourselves.

In spite of this, I think there is still a place for theodicies - just as there is a place for ontological arguments - provided they originate with the believer and are not forced upon her. The mourner who chooses to believe that the dearly departed have gone to well-earned rest may believe that. That belief may be the germination of the seeds of honor and love, or the expression of grief combined with commitment to the flourishing of the memory of the beloved - it may be the fruit of the idea that the cosmos has no right to bring this love to an end. You may destroy the body, but the soul you shall not take from me.

| ||

| My great aunt and great uncle. Here lie their bodies. |