museums

∞

No Flash!

My job as a college professor brings me to a lot of museums and archives, and this summer has been especially full of visits to museums, historical sites, and archives in Greece, Norway, the U.K., and the U.S.

As a kid I found most museums boring, but now I really appreciate and enjoy them. I've spent many days of my life in the British Museum and in several museums in Athens, and each time I'm there I feel that time is rewarded with fresh discoveries and with reacquaintance with familiar objects.

Some museums have a reasonable policy of not permitting flash photography, since the bright light of camera flashes can degrade the colors of paint and dyes. Others must insist on no photography when the objects on display are on loan from owners who will not permit reproductions of their images.

But in general, I object when museums and archives prohibit photography, especially when the aim is to force more visitors to come to the physical site. Most people the world over will never be able to visit the world's great museums. And many scholars could benefit from digital images of archival materials. During a recent visit to an archive that hosts many of Henry David Thoreau's papers, I was disappointed to learn that I would not be permitted to take photos of some of the papers I wanted to read later. This forces scholars to spend more time in the archive, which means spending more money - simply prohibitive for many of us. So I type, or scribble, as quickly as I can to transcribe texts in some archives, and hope that I can somehow find what I need in the time I have.

The Ballpoint As A Tool For Seeing

But what if what you want to remember is not a text but an image? Scott Parsons, a gifted artist and a friend of mine, has taught me that one need not be very talented with a pen to begin to capture images. As Dr. Cornelius said in one of Lewis's stories, "A scholar is never without [pen and paper]," and I've tried to make that my rule, too, carrying pen and paper with me everywhere. Scott tells me that a cheap ballpoint pen is, after all, one of the best tools for seeing.

It turns out, he's right: the pen is often mightier than the camera. I think this is because the camera captures all available light, while the pen only captures what my eye and hand tell it to. The chief obstacle to overcome is the disconnect between what my eye sees and what my hand draws. Scott has pointed out to me that this is not the fault of my hand so much as a problem of mistaking what I think I see for what I actually see. In other words, it is a problem of misdirected attention, when I pay attention to what I think is there rather than to what the light is actually doing.

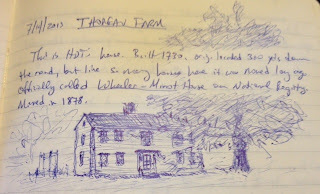

So far, no one in any museum has objected to my drawing what I see. In most cases, when I draw pictures, people seem honored that I should take the time. I drew this picture of the Thoreau homestead in Concord this summer, and a curator there happened to see it as I journaled. She seemed pleased that I took the time to try to draw it. I find that taking the time to draw helps me to notice details I'd have otherwise missed. You can see I'm not a great artist, little improved from my youth. But I'm not ashamed, because even if it's not a brilliant representation, it doesn't need to be; it is a record, in blue lines, of ten minutes of attention. The image is not a photograph; it is a symbol of memory, like a call number for a book in a library that helps me to recall quickly the time I spent sitting on the grass in Concord considering the place where Henry David grew up.

Memories Of Delight

I've also begun drawing inside people's homes when I'm a guest there - always with permission, of course. This summer several kind Norwegian friends took me in for a week, giving me space to write while overlooking a fjord, and cooking me delicious Norwegian food. In the evening we built fires in the hearth and talked quietly or played cards. These are fond memories with friends, but they're also memories of delight in seeing new shapes of things. Norwegians build fires and eat waffles as we Americans do, but the fireplaces and the waffle irons are different from the ones I know from my home. The waffles I saw were all shaped like heart-flowers, giving visual delight in addition to the delightful taste (though I'm not yet sold on brown cheese as a topping.) The fireplaces I saw were all open on not just one side, but two. They looked different, but it was only when I began to draw them that I noticed what I was seeing. This is a small thing, perhaps, but it is a reminder that what I take to be the natural shape of things often has as much to do with the traditions I grew up with as with nature. As an aside, when I take the time to draw pictures, it often seems to be taken as a sign of respect, which is just how I intend it: this place you live in, this object in your home, is so wonderful to me that I wish to give it my attention and make it a permanent resident in my journal, the log-book of my heart. May I? Thank you, and thank you for the hospitality that allowed me to witness this.

Pics Or It Didn't Happen

Sometimes I choose not to take photos simply because the camera is itself a sign. When we hold it in front of our face, it becomes not just a lens through which we see, but a symbol of distance: this moment, this image, matters because it will matter somewhere else, somewhen else. There's nothing wrong with wanting to preserve the moment, but when the apparatus becomes the medium through which we perceive everything - when we feel we must record a photonic image of everything to make the moment real, reality itself somehow becomes less to us.

Icons As Luminous Doorways

This summer I had the privilege of visiting the Monastery of Hosios (Saint) Loukas near Delphi in Greece. I'm not Orthodox, but I have real appreciation for what I learn from the Orthodox traditions. An Orthodox priest in my town has told me that icons are not objects of worship, but means of worship, images that help us to pray, just as windows help us to see. The pray-er who regards the icon isn't supposed to see the icon, but, as with windows, to see through the icon. In some sense the artistic image is intended to vanish when it is doing what it was intended to do. This language has been a little bit mysterious to me at times, but at the monastery this summer I had an illustrative experience: I stood in a doorway with bright sunlight shining behind me. Ahead, I could see through another doorway into the narthex of a chapel, and then through another doorway, to the altar at the far end. Beside every Orthodox altar there is an icon of Christ. This one was covered with glass, as icons often are. The glass reflected back to me the image of the doorway behind me, as though in the center of the image of Christ there were a luminous doorway. I tried to take a photo of this, but the contrasts were too great. So I took out my paper and pen and sketched what I saw. It's not a superb image, but it turned out far better than my photographic attempts did. And, as in other cases, I found myself feeling considerably more present and more respectful of the place.

The View From The Pew

This was the case with several other holy sites I visited this summer as well. I had the privilege of hearing Robert Richardson lecture on Emerson in the Unitarian church in Concord, MA this summer, and then to visit the "African Meeting House" in Boston, a site of worship and of community activism for African Americans in the 19th century. It somehow didn't feel right to let the camera intrude into these places. The pen, by contrast, felt like an instrument properly reverent. Each stroke of the pen strengthening lines became like a prayer or an act of gratitude and reverence for the places I was in. In each case I sketched a "view from my pew," the view I had while sitting as worshipers have sat there in times past - and present.

No Photos!

But to return to the complaint with which I began this piece, too many places insist that no photography be allowed inside. While participating in a Summer Institute on Transcendentalism sponsored by the National Endowment for the Humanities this summer, I was able to visit some wonderful places, like the Thoreau Homestead, several of the homes of Louisa May Alcott, and Emerson's home. Visiting these places makes me a better teacher: they help me to tell a better story about the texts and ideas that emerged from them. Bronson Alcott, Louisa May's father, may have been odd, but his oddity is fascinating and delightful. He built this outbuilding to house his Concord School of Philosophy, for instance:

Architecture As The Embodiment Of Ideas

And he had some beautiful ideas about education: like the belief that children should be allowed to learn what they love to learn, that they should become bodily and sensorily engaged in their learning, that they should run and play and have recess, that art and literature should be significant in their learning, and so on. I knew these ideas before visiting his Concord home and Fruitlands, but seeing the buildings he built to house his ideas helps me to see how he envisioned those ideas at work.

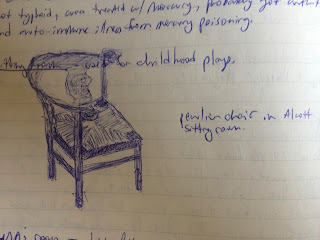

Unfortunately, I can only show you the outside of the buildings at the Alcott house, because there's no photography allowed inside, nor at the Emerson home either. So if you live far away, tant pis. I guess you'll have to just travel and visit it. Or, if you like, I can share the sketches I was able to make in our hurried tour. Yes, let's do that. I loved this chair, which is so oddly shaped. In a time when so many chairs seemed intended to make you sit ramrod straight, this one seems to invite you to slouch in different directions, to be at ease in your own body, to delight in sitting in the company of others:

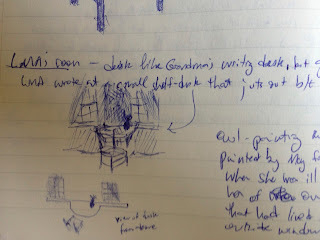

The Alcotts weren't wealthy, but Bronson and his wife managed to provide each of their children with a room of their own, and each of those rooms is suited to the disposition and arts of the child. Louisa May's room has a beautiful little half-moon shelf-desk jutting out between two large windows, perfect for writing stories and books, with excellent light. When I visited, the room was full of tourists, so a photo wouldn't have captured it anyway, and my drawing is very hasty and a little cramped itself, but here's a rough idea of what it looks like while standing beside her bed, plus an attempt to give the bird's-eye view:

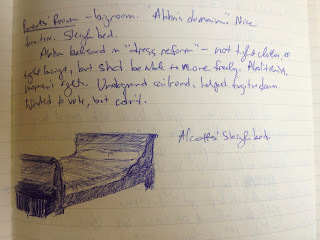

Bronson and his wife Abby had some lovely furniture, and I was especially captivated by their sleigh-bed. Its curved ends and gentle woodwork make the bed seem a place worth being, a place of rest and delight:

What I wish is that the owners and curators of these places would recognize that allowing visitors to take photos can help us to preserve the very places we are visiting, and to teach others about them. I understand the desire to make those places special, just as I understand the fear that if you allow images to be taken maybe fewer visitors will come. But for us teachers, taking pictures can be a way to allow our students to visit a place they might otherwise never go.

Thankfully, no one has yet prohibited my pen and paper. Or yours. I'm not up to Urban Sketchers quality, and may never be, but I'm not ashamed to use my pen as a visual instrument, nor to share with you what I've seen through it. And I hope you'll do the same.

Rebel Without A Camera: Museums, Images, and Memory

|

| My old Brownie. No flash! |

As a kid I found most museums boring, but now I really appreciate and enjoy them. I've spent many days of my life in the British Museum and in several museums in Athens, and each time I'm there I feel that time is rewarded with fresh discoveries and with reacquaintance with familiar objects.

Some museums have a reasonable policy of not permitting flash photography, since the bright light of camera flashes can degrade the colors of paint and dyes. Others must insist on no photography when the objects on display are on loan from owners who will not permit reproductions of their images.

But in general, I object when museums and archives prohibit photography, especially when the aim is to force more visitors to come to the physical site. Most people the world over will never be able to visit the world's great museums. And many scholars could benefit from digital images of archival materials. During a recent visit to an archive that hosts many of Henry David Thoreau's papers, I was disappointed to learn that I would not be permitted to take photos of some of the papers I wanted to read later. This forces scholars to spend more time in the archive, which means spending more money - simply prohibitive for many of us. So I type, or scribble, as quickly as I can to transcribe texts in some archives, and hope that I can somehow find what I need in the time I have.

The Ballpoint As A Tool For Seeing

But what if what you want to remember is not a text but an image? Scott Parsons, a gifted artist and a friend of mine, has taught me that one need not be very talented with a pen to begin to capture images. As Dr. Cornelius said in one of Lewis's stories, "A scholar is never without [pen and paper]," and I've tried to make that my rule, too, carrying pen and paper with me everywhere. Scott tells me that a cheap ballpoint pen is, after all, one of the best tools for seeing.

It turns out, he's right: the pen is often mightier than the camera. I think this is because the camera captures all available light, while the pen only captures what my eye and hand tell it to. The chief obstacle to overcome is the disconnect between what my eye sees and what my hand draws. Scott has pointed out to me that this is not the fault of my hand so much as a problem of mistaking what I think I see for what I actually see. In other words, it is a problem of misdirected attention, when I pay attention to what I think is there rather than to what the light is actually doing.

|

| Thoreau Farm |

|

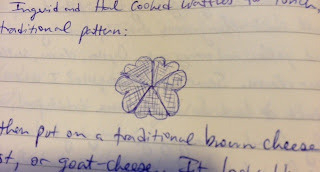

| Norwegian waffle: a bouquet of hearts |

|

| Norwegian fireplace |

I've also begun drawing inside people's homes when I'm a guest there - always with permission, of course. This summer several kind Norwegian friends took me in for a week, giving me space to write while overlooking a fjord, and cooking me delicious Norwegian food. In the evening we built fires in the hearth and talked quietly or played cards. These are fond memories with friends, but they're also memories of delight in seeing new shapes of things. Norwegians build fires and eat waffles as we Americans do, but the fireplaces and the waffle irons are different from the ones I know from my home. The waffles I saw were all shaped like heart-flowers, giving visual delight in addition to the delightful taste (though I'm not yet sold on brown cheese as a topping.) The fireplaces I saw were all open on not just one side, but two. They looked different, but it was only when I began to draw them that I noticed what I was seeing. This is a small thing, perhaps, but it is a reminder that what I take to be the natural shape of things often has as much to do with the traditions I grew up with as with nature. As an aside, when I take the time to draw pictures, it often seems to be taken as a sign of respect, which is just how I intend it: this place you live in, this object in your home, is so wonderful to me that I wish to give it my attention and make it a permanent resident in my journal, the log-book of my heart. May I? Thank you, and thank you for the hospitality that allowed me to witness this.

Pics Or It Didn't Happen

Sometimes I choose not to take photos simply because the camera is itself a sign. When we hold it in front of our face, it becomes not just a lens through which we see, but a symbol of distance: this moment, this image, matters because it will matter somewhere else, somewhen else. There's nothing wrong with wanting to preserve the moment, but when the apparatus becomes the medium through which we perceive everything - when we feel we must record a photonic image of everything to make the moment real, reality itself somehow becomes less to us.

|

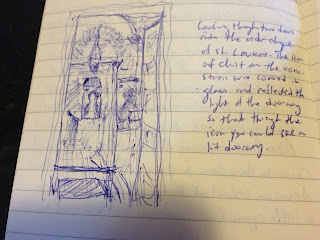

| Ecce: the heart of Christ, a luminous doorway |

This summer I had the privilege of visiting the Monastery of Hosios (Saint) Loukas near Delphi in Greece. I'm not Orthodox, but I have real appreciation for what I learn from the Orthodox traditions. An Orthodox priest in my town has told me that icons are not objects of worship, but means of worship, images that help us to pray, just as windows help us to see. The pray-er who regards the icon isn't supposed to see the icon, but, as with windows, to see through the icon. In some sense the artistic image is intended to vanish when it is doing what it was intended to do. This language has been a little bit mysterious to me at times, but at the monastery this summer I had an illustrative experience: I stood in a doorway with bright sunlight shining behind me. Ahead, I could see through another doorway into the narthex of a chapel, and then through another doorway, to the altar at the far end. Beside every Orthodox altar there is an icon of Christ. This one was covered with glass, as icons often are. The glass reflected back to me the image of the doorway behind me, as though in the center of the image of Christ there were a luminous doorway. I tried to take a photo of this, but the contrasts were too great. So I took out my paper and pen and sketched what I saw. It's not a superb image, but it turned out far better than my photographic attempts did. And, as in other cases, I found myself feeling considerably more present and more respectful of the place.

|

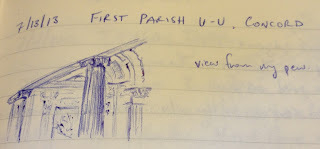

| First Parish, Concord, Mass. |

|

| African Meeting House, Boston, Mass. |

This was the case with several other holy sites I visited this summer as well. I had the privilege of hearing Robert Richardson lecture on Emerson in the Unitarian church in Concord, MA this summer, and then to visit the "African Meeting House" in Boston, a site of worship and of community activism for African Americans in the 19th century. It somehow didn't feel right to let the camera intrude into these places. The pen, by contrast, felt like an instrument properly reverent. Each stroke of the pen strengthening lines became like a prayer or an act of gratitude and reverence for the places I was in. In each case I sketched a "view from my pew," the view I had while sitting as worshipers have sat there in times past - and present.

No Photos!

But to return to the complaint with which I began this piece, too many places insist that no photography be allowed inside. While participating in a Summer Institute on Transcendentalism sponsored by the National Endowment for the Humanities this summer, I was able to visit some wonderful places, like the Thoreau Homestead, several of the homes of Louisa May Alcott, and Emerson's home. Visiting these places makes me a better teacher: they help me to tell a better story about the texts and ideas that emerged from them. Bronson Alcott, Louisa May's father, may have been odd, but his oddity is fascinating and delightful. He built this outbuilding to house his Concord School of Philosophy, for instance:

|

| Alcott's Concord School of Philosophy, Orchard House |

And he had some beautiful ideas about education: like the belief that children should be allowed to learn what they love to learn, that they should become bodily and sensorily engaged in their learning, that they should run and play and have recess, that art and literature should be significant in their learning, and so on. I knew these ideas before visiting his Concord home and Fruitlands, but seeing the buildings he built to house his ideas helps me to see how he envisioned those ideas at work.

|

| Chair in the Orchard House |

|

| Louisa May Alcott's writing desk |

|

| The Alcotts' sleigh-bed |

What I wish is that the owners and curators of these places would recognize that allowing visitors to take photos can help us to preserve the very places we are visiting, and to teach others about them. I understand the desire to make those places special, just as I understand the fear that if you allow images to be taken maybe fewer visitors will come. But for us teachers, taking pictures can be a way to allow our students to visit a place they might otherwise never go.

Thankfully, no one has yet prohibited my pen and paper. Or yours. I'm not up to Urban Sketchers quality, and may never be, but I'm not ashamed to use my pen as a visual instrument, nor to share with you what I've seen through it. And I hope you'll do the same.

∞

Visual Art and the Sacred: On The Importance Of Museums

I just finished writing an essay about the day Picasso made me fall down. I'm sending it off to my favorite editor, and if it's accepted, I'll post a link here.

The event I wrote about took place over two decades ago, when Picasso's Guernica was still housed in the Casón del Buen Retiro at the Prado Museum in Madrid. (It is now in the Reina Sofia, in a larger but - in my opinion - far inferior room. You can learn a bit about that here.)

Meanwhile, here's the upshot of my essay: education that's prepackaged and canned is not enough. Education is not the same as transferring information.

It involves informing students, to be sure, but what we tell students

should not satisfy them; it should provoke them to want more. Professors are not conduits of data; at our best we are like guides and gardeners.

As guides we point students in new directions and help them to see what

we see. Just as gardeners cannot make seeds grow but can prepare the

soil, so our teaching should be about increasing the fertility of minds

and then stepping back to watch what grows. Also, there is occasional

weeding involved.

As an undergraduate I knew very little about art. Part of this was my disposition: I liked representational art that was easy to look at quickly. Part of it was a matter of my worldview, and the suspicion that some modern artists who eschewed representational art were trying to undermine something good, obscurantists clouding clear vision.

Time spent in museums has changed me a good deal, as has making the acquaintance of Scott Parsons and Daniel Siedell, who have helped me quite a lot through their patient conversation and what they have written. (Scott and I wrote a chapter on teaching students about visual culture and the sacred in Ronald Bernier's short but illuminating book Beyond Belief, in which Dan also has a chapter.) Some of Makoto Fujimura's short writings, James Elkins's book On the Strange Place of Religion in Modern Art, and Gregory Wolfe's work at Image have also provided me with clear and helpful education about art that I resisted when I was younger.

Museums are certainly controversial. Curators make decisions that both expand and limit what we see, and this can be exploited to achieve sordid political ends. Some ideas and cultures are given preferential treatment while others are made less known by their omission. They tend to be located in large, wealthy cities, which means that poor people, rural people, and foreigners have limited or no access to them. But if the alternative is no museums, or all of the world's artifacts in private collections, I will take the museums we have, coupled with ever striving to make them better.

Because museums are a tangible way we can commit to remembering our history together. Museums are not safe deposit boxes where we lock away our treasures; they are Wunderkammers and classrooms where we may think and learn together.

I have come to love museums, especially the British Museum and the beautiful New Acropolis Museum in Athens (and I'm aware of the irony of that pairing) but I also love the little museums I find in small towns the world over.

The event I wrote about took place over two decades ago, when Picasso's Guernica was still housed in the Casón del Buen Retiro at the Prado Museum in Madrid. (It is now in the Reina Sofia, in a larger but - in my opinion - far inferior room. You can learn a bit about that here.)

|

| New Acropolis Museum, Athens |

As an undergraduate I knew very little about art. Part of this was my disposition: I liked representational art that was easy to look at quickly. Part of it was a matter of my worldview, and the suspicion that some modern artists who eschewed representational art were trying to undermine something good, obscurantists clouding clear vision.

Time spent in museums has changed me a good deal, as has making the acquaintance of Scott Parsons and Daniel Siedell, who have helped me quite a lot through their patient conversation and what they have written. (Scott and I wrote a chapter on teaching students about visual culture and the sacred in Ronald Bernier's short but illuminating book Beyond Belief, in which Dan also has a chapter.) Some of Makoto Fujimura's short writings, James Elkins's book On the Strange Place of Religion in Modern Art, and Gregory Wolfe's work at Image have also provided me with clear and helpful education about art that I resisted when I was younger.

Museums are certainly controversial. Curators make decisions that both expand and limit what we see, and this can be exploited to achieve sordid political ends. Some ideas and cultures are given preferential treatment while others are made less known by their omission. They tend to be located in large, wealthy cities, which means that poor people, rural people, and foreigners have limited or no access to them. But if the alternative is no museums, or all of the world's artifacts in private collections, I will take the museums we have, coupled with ever striving to make them better.

Because museums are a tangible way we can commit to remembering our history together. Museums are not safe deposit boxes where we lock away our treasures; they are Wunderkammers and classrooms where we may think and learn together.

I have come to love museums, especially the British Museum and the beautiful New Acropolis Museum in Athens (and I'm aware of the irony of that pairing) but I also love the little museums I find in small towns the world over.

∞

Writing, Law, and Memory in Ancient Gortyn

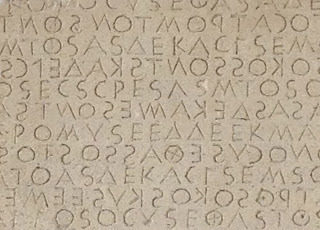

In the ruins of Gortyn, in central Crete, some of the famous ancient laws of Crete are preserved in stone. Archaeologists uncovered them in 1884, and have since built a brick enclosure to protect them from the weather.

Even though I'm not an expert in the Doric dialect, I love to read this inscription, for several reasons that might interest even those who don't know Greek.

First of all, it has an unusual alphabet, containing fewer letters than modern or classical Attic Greek. It lacks the vowels eta and omega (for which it uses epsilon and omicron), and the consonants zeta, xi, phi, chi, and psi (for which it substitutes other letters or combinations of other letters: two deltas for zeta, kappa+sigma for xi; pi for phi; kappa for chi; pi+sigma for psi.)

It also uses a letter that has since fallen out of use, the digamma. The digamma (or wau) is probably related to the Hebrew letter waw (or vav) and to the Roman letter F, which it closely resembles. By the classical age it had dropped out of use in Greek, and is fairly rare, like the letters sampi and qoppa.

(There is also a digamma in Delphi, not far from the Athena Pronaia sanctuary, on an upright stone dedicated to Athenai Warganai. That second word is related to the Greek word for "work" or "deed," ergon, and also to our word "work." This stone, pictured below, evinces several peculiarities of archaic Greek script. Look at the second word, which looks like it says FARCANAI. The first letter is digamma; the third letter, rho, very much resembles the Latin "R"; the letter immediately after it, gamma, looks like a flattened upper-case "C.")

Second, the writing is in boustrophedon style. Boustrophedon means something like "as the ox turns." Today we write in stoichedon style, in which all the letters face the same direction, like soldiers standing in formation. Boustrophedon is based on an agricultural, not a military ideal: the writer writes as a farmer plows. Write to the end of the line, and then, rather than returning to the left side of the page, turn the letters to face the opposite direction and write from right to left. When you read boustrophedon, your eye follows a zig-zag across the page -- or the stone.

Have a look at this close-up of the engraving at Gortys and look at the way letters like "E," "K," and "S" face in adjacent lines:

(By the way, that "S" character is actually an iota; sigmas look like this: M; mu is like our "M" with an extra stroke added.)

There are a lot of other reasons to like this place, and this inscription, but I'll limit myself to just one more thing for now: memory.

This inscription is one way that an ancient community deliberately remembered their laws. They wrote down what they decided, and that has affected our lives. Writing the law down makes it accessible to everyone, and makes judicial decisions transparent. It establishes a set of expectations for conduct in the community, and makes those expectations known even to aliens.

The code at Gortyn records (in Column IX, around the middle, if you're curious) the presence at court of someone in addition to the judge: the mnemon. You can see by the word's resemblance to our word "mnemonic" that it has to do with memory. The mnemon's job was to act as a witness to previous judicial decisions, and to remember them and remind the judge of those decisions. The mnemon's job was not to decide cases but to be a kind of embodiment of the law and therefore an embodiment of fairness.

Unfortunately, no mnemon lives forever. Presumably, the writing on the wall at Gortyn was a way of preserving what mattered most in the court, so that when they passed away, their memories would live on through the ages.

*****

Harold Fowler writes in a footnote to his 1921 translation of the Cratylus that under Eucleides the Athenians officially changed their alphabet from the archaic one to the Ionian alphabet in 404/403 BCE. This expanded their system of vowels, adding the long vowels eta and omega. It became known as the Euclidean Alphabet.

*****

If you can find it, Adonis Vasilakis' The Great Inscription of the Law Code of Gortyn (Heraklion/Iraklio: Mystis O.E.) is a great resource. It has a facsimile of the whole wall, a complete translation, and some helpful historical observations. ISBN 9608853400

|

| Gortyn, Crete |

Even though I'm not an expert in the Doric dialect, I love to read this inscription, for several reasons that might interest even those who don't know Greek.

First of all, it has an unusual alphabet, containing fewer letters than modern or classical Attic Greek. It lacks the vowels eta and omega (for which it uses epsilon and omicron), and the consonants zeta, xi, phi, chi, and psi (for which it substitutes other letters or combinations of other letters: two deltas for zeta, kappa+sigma for xi; pi for phi; kappa for chi; pi+sigma for psi.)

It also uses a letter that has since fallen out of use, the digamma. The digamma (or wau) is probably related to the Hebrew letter waw (or vav) and to the Roman letter F, which it closely resembles. By the classical age it had dropped out of use in Greek, and is fairly rare, like the letters sampi and qoppa.

(There is also a digamma in Delphi, not far from the Athena Pronaia sanctuary, on an upright stone dedicated to Athenai Warganai. That second word is related to the Greek word for "work" or "deed," ergon, and also to our word "work." This stone, pictured below, evinces several peculiarities of archaic Greek script. Look at the second word, which looks like it says FARCANAI. The first letter is digamma; the third letter, rho, very much resembles the Latin "R"; the letter immediately after it, gamma, looks like a flattened upper-case "C.")

|

|

"Athenai Warganai" inscription at Delphi

|

Second, the writing is in boustrophedon style. Boustrophedon means something like "as the ox turns." Today we write in stoichedon style, in which all the letters face the same direction, like soldiers standing in formation. Boustrophedon is based on an agricultural, not a military ideal: the writer writes as a farmer plows. Write to the end of the line, and then, rather than returning to the left side of the page, turn the letters to face the opposite direction and write from right to left. When you read boustrophedon, your eye follows a zig-zag across the page -- or the stone.

Have a look at this close-up of the engraving at Gortys and look at the way letters like "E," "K," and "S" face in adjacent lines:

|

| Close-up of the Gortyn Code |

There are a lot of other reasons to like this place, and this inscription, but I'll limit myself to just one more thing for now: memory.

This inscription is one way that an ancient community deliberately remembered their laws. They wrote down what they decided, and that has affected our lives. Writing the law down makes it accessible to everyone, and makes judicial decisions transparent. It establishes a set of expectations for conduct in the community, and makes those expectations known even to aliens.

The code at Gortyn records (in Column IX, around the middle, if you're curious) the presence at court of someone in addition to the judge: the mnemon. You can see by the word's resemblance to our word "mnemonic" that it has to do with memory. The mnemon's job was to act as a witness to previous judicial decisions, and to remember them and remind the judge of those decisions. The mnemon's job was not to decide cases but to be a kind of embodiment of the law and therefore an embodiment of fairness.

Unfortunately, no mnemon lives forever. Presumably, the writing on the wall at Gortyn was a way of preserving what mattered most in the court, so that when they passed away, their memories would live on through the ages.

|

| National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Possibly a child's dish? The sixth letter is digamma. |

*****

Harold Fowler writes in a footnote to his 1921 translation of the Cratylus that under Eucleides the Athenians officially changed their alphabet from the archaic one to the Ionian alphabet in 404/403 BCE. This expanded their system of vowels, adding the long vowels eta and omega. It became known as the Euclidean Alphabet.

*****

If you can find it, Adonis Vasilakis' The Great Inscription of the Law Code of Gortyn (Heraklion/Iraklio: Mystis O.E.) is a great resource. It has a facsimile of the whole wall, a complete translation, and some helpful historical observations. ISBN 9608853400