music

∞

Amy Grant’s new song

In which two philosophy professors, a pastor, and a folk musician talk about Amy Grant: jaaronsimmons.substack.com/p/discuss…

∞

On Church Organs and Church Music

Recently I had the good fortune to hear an organ concert in Westminster Abbey. Not long afterwards I heard someone asking whether churches should get rid of their old organs. The question is a reasonable one, since organs are expensive to maintain, nigh impossible to move, and not many people can play them well. To those charges we should add the charge that organs are old-fashioned, and we are not.

I happen to love organ music, so that's one reason why I think we shouldn't get rid of the organs that remain in our churches. But there is at least one more important reason to think carefully about replacing them. Sometimes organs don't fit well with the buildings they are in, as though the organ was purchased on its own merits and not for the way it matched the acoustics of the building that holds it. In those cases, I don't see the loss if they're removed.

But this is a failing of architecture and economics, not just of music. The problem in that case is far greater than the sin of not being contemporary. An organ that does not match the church, or a church that is not made to be acoustically beautiful - both of these are failures, the kind of failure that comes from people who think that design and aesthetics are luxuries. But design is never neutral; it always helps or hurts. Efficiencies and economics can be the enemies of accomplishing the most worthwhile ends.

Here's what Westminster Abbey reminded me of: a well-built organ is not just an instrument; it is a part of the edifice itself. Specifically, it is the part that turns the whole edifice into a musical instrument. When the organ at Westminster is being played, it is not just a keyboard or pipes that are being played, but the whole building. Every bit of the building resounds. The music is not an isolated event anymore; the notes played and the place in which they are played have merged, and each reaches out to affirm the other. A good organ turns a church into a musical instrument.

Too often churches think of aesthetics last, if at all, or refuse to make aesthetics part of their theology. This is a huge mistake. The prophets describe the architectural adornments of the Ark and the Tabernacle and the Temple, giving those aesthetical elements a permanent place in Jewish and Christian canonical scripture. Similarly, the scriptures are full of songs and poems that - one could argue - are unnecessary to salvation. As Scott Parsons and I have argued, art and the sacred belong together. Our faith is not a matter of mere talk; sometimes what must be articulated cannot be said in words, but needs the smell of incense, the ringing of a sanctus bell, the deep bellow of a pipe organ, the beauty of light well-captured in glass or terrazzo.

If you're not sure of what I mean, listen to Árstí∂ir sing the medieval hymn Heyr himna smi∂ur -- in a train station. Can you imagine that being sung in a church with similar acoustics? Here's what I love about the video: when they sing that beautiful old song, everyone around them stops to listen. The beauty of the song is arresting, especially when it is paired with the building. What keeps us from dreaming of building churches, writing music, and designing instruments that could similarly arrest us?

I happen to love organ music, so that's one reason why I think we shouldn't get rid of the organs that remain in our churches. But there is at least one more important reason to think carefully about replacing them. Sometimes organs don't fit well with the buildings they are in, as though the organ was purchased on its own merits and not for the way it matched the acoustics of the building that holds it. In those cases, I don't see the loss if they're removed.

But this is a failing of architecture and economics, not just of music. The problem in that case is far greater than the sin of not being contemporary. An organ that does not match the church, or a church that is not made to be acoustically beautiful - both of these are failures, the kind of failure that comes from people who think that design and aesthetics are luxuries. But design is never neutral; it always helps or hurts. Efficiencies and economics can be the enemies of accomplishing the most worthwhile ends.

Here's what Westminster Abbey reminded me of: a well-built organ is not just an instrument; it is a part of the edifice itself. Specifically, it is the part that turns the whole edifice into a musical instrument. When the organ at Westminster is being played, it is not just a keyboard or pipes that are being played, but the whole building. Every bit of the building resounds. The music is not an isolated event anymore; the notes played and the place in which they are played have merged, and each reaches out to affirm the other. A good organ turns a church into a musical instrument.

Too often churches think of aesthetics last, if at all, or refuse to make aesthetics part of their theology. This is a huge mistake. The prophets describe the architectural adornments of the Ark and the Tabernacle and the Temple, giving those aesthetical elements a permanent place in Jewish and Christian canonical scripture. Similarly, the scriptures are full of songs and poems that - one could argue - are unnecessary to salvation. As Scott Parsons and I have argued, art and the sacred belong together. Our faith is not a matter of mere talk; sometimes what must be articulated cannot be said in words, but needs the smell of incense, the ringing of a sanctus bell, the deep bellow of a pipe organ, the beauty of light well-captured in glass or terrazzo.

[youtube=[www.youtube.com/watch](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e4dT8FJ2GE0&w=320&h=266])

If you're not sure of what I mean, listen to Árstí∂ir sing the medieval hymn Heyr himna smi∂ur -- in a train station. Can you imagine that being sung in a church with similar acoustics? Here's what I love about the video: when they sing that beautiful old song, everyone around them stops to listen. The beauty of the song is arresting, especially when it is paired with the building. What keeps us from dreaming of building churches, writing music, and designing instruments that could similarly arrest us?

∞

All Your Deeds

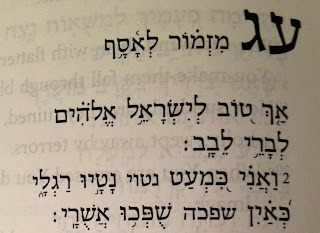

I just read the seventy-third psalm. I don't understand much of it, but it begins with a complaint about injustice, and I certainly feel like I get that part.

The last line caused me some trouble, though. In it Asaph, the psalmist, says "I will tell of all your [God's] deeds."

Okay, what exactly are those deeds? What can we ever reliably say about God's deeds? If God had done something in history that were not open to historical doubt, there would be no atheists.

The tradition gives us stories about God, and a century of biblical criticism calls those stories myths. Still, as I have argued elsewhere (here, and here, for example) myth is not - or should not be taken as - a synonym for falsehood. Stories may be myths and true, even if not historically true.

As Howard Wettstein argues in his Significance of Religious Experience,

Which makes me wonder: what roles does God play in my life? What "deeds" may I speak of?

Before I reply, let me hasten to say this: I am often reluctant to write too strongly about this sort of thing because I do not want to say that others must believe what I believe. If God has led me to belief, (grant me that for the sake of argument for a moment) God has not strong-armed me into belief but allowed me to arrive at my beliefs over time, letting them be shaped by experience. I do not see why I should allow you less liberty than God has allowed me.

So I write the following admitting that I do not know what I am writing about. As Augustine confessed, when I speak of my love for God, I do so simultaneously wondering what I mean by "God." What can I compare God to? What is God like? I do not know how to answer those questions, except by telling stories, expositing roles. So here goes:

When I was a child, belief in God motivated a family in my neighborhood to care about me and to welcome me into their home when my family was falling apart. Without that love...I shudder to think what I would be today.

God gives me a name for what I pray to. God gives me a focal point for my attention in the vast cosmos, and God gives me a sense that in such a cosmos persons matter. And because persons matter, justice matters. This is not to say one cannot be just without belief, or that belief makes one just - far from it! - only that I find for myself the two ideas closely bound together.

God gives me solace in my mourning and hope when I pray. My mother is dead, but when I speak to God about her, she is not lost.

God gives me a story about the centrality of nurturing love. A reason to think all things are related. Someone to thank. Someone to be angry with. Rest for my soul. Quietness, and in it, trust.

God gives me a story about giving, and why giving and receiving should matter so much.

A story about why, and how, to turn a guilty conscience into repentance. A reason to forgive, and, very often, the strength to forgive. And to hope that I too am forgivable.

A reason to hope that no one is beyond redemption, beyond all hope, completely unworthy of love.

Belief that every person matters. More than that, belief that a teenage girl could be a vessel of the divine; that a third-world martyred prophet could save the world; that an inarticulate foreigner could be a world-historical lawgiver; that a persecuting zealot could get hit so hard by grace that he lives the rest of his life to preach good news for all people everywhere.

Hope that prison doors could be opened, that tongues could be loosed, that great art and great music might be signs of the divine.

I could be wrong about all of this, I know. I know there are other explanations of what I have written above. I also know those explanations apply to music, too, and I'm not interested in hearing about them there either if the reason for offering them is to help disabuse me of my love for good music. I know that people use the same word I use here to justify violence, self-interest, and hatred. I cannot help but feel angry and disgusted when it is used for those ends, ends which seem so contrary to what the word means for me, ends that make me think someone has read the wrong script, mis-cast the character, not known what deeds God has done.

The last line caused me some trouble, though. In it Asaph, the psalmist, says "I will tell of all your [God's] deeds."

Okay, what exactly are those deeds? What can we ever reliably say about God's deeds? If God had done something in history that were not open to historical doubt, there would be no atheists.

The tradition gives us stories about God, and a century of biblical criticism calls those stories myths. Still, as I have argued elsewhere (here, and here, for example) myth is not - or should not be taken as - a synonym for falsehood. Stories may be myths and true, even if not historically true.

As Howard Wettstein argues in his Significance of Religious Experience,

The Bible’s characteristic mode of ‘theology’ is story telling, the stories overlaid with poetic language. Never does one find the sort of conceptually refined doctrinal propositions characteristic of a doctrinal approach. When the divine protagonist comes into view, we are not told much about his properties. Think about the divine perfections, the highly abstract omni-properties (omnipotence, omniscience, and the like), so dominant in medieval and post-medieval theology. One has to work very hard—too hard—to find even hints of these in the Biblical text. Instead of properties, perfection and the like the Bible speaks of God’s roles—father, king, friend, lover, judge, creator, and the like. Roles, as opposed to properties; this should give one pause. (108, emphasis added)The stories may not be about historical "deeds" but may be about the character, the roles of God.

Which makes me wonder: what roles does God play in my life? What "deeds" may I speak of?

|

| The preface to the complaint in Psalm 73 |

Before I reply, let me hasten to say this: I am often reluctant to write too strongly about this sort of thing because I do not want to say that others must believe what I believe. If God has led me to belief, (grant me that for the sake of argument for a moment) God has not strong-armed me into belief but allowed me to arrive at my beliefs over time, letting them be shaped by experience. I do not see why I should allow you less liberty than God has allowed me.

So I write the following admitting that I do not know what I am writing about. As Augustine confessed, when I speak of my love for God, I do so simultaneously wondering what I mean by "God." What can I compare God to? What is God like? I do not know how to answer those questions, except by telling stories, expositing roles. So here goes:

When I was a child, belief in God motivated a family in my neighborhood to care about me and to welcome me into their home when my family was falling apart. Without that love...I shudder to think what I would be today.

God gives me a name for what I pray to. God gives me a focal point for my attention in the vast cosmos, and God gives me a sense that in such a cosmos persons matter. And because persons matter, justice matters. This is not to say one cannot be just without belief, or that belief makes one just - far from it! - only that I find for myself the two ideas closely bound together.

God gives me solace in my mourning and hope when I pray. My mother is dead, but when I speak to God about her, she is not lost.

God gives me a story about the centrality of nurturing love. A reason to think all things are related. Someone to thank. Someone to be angry with. Rest for my soul. Quietness, and in it, trust.

God gives me a story about giving, and why giving and receiving should matter so much.

A story about why, and how, to turn a guilty conscience into repentance. A reason to forgive, and, very often, the strength to forgive. And to hope that I too am forgivable.

A reason to hope that no one is beyond redemption, beyond all hope, completely unworthy of love.

Belief that every person matters. More than that, belief that a teenage girl could be a vessel of the divine; that a third-world martyred prophet could save the world; that an inarticulate foreigner could be a world-historical lawgiver; that a persecuting zealot could get hit so hard by grace that he lives the rest of his life to preach good news for all people everywhere.

Hope that prison doors could be opened, that tongues could be loosed, that great art and great music might be signs of the divine.

I could be wrong about all of this, I know. I know there are other explanations of what I have written above. I also know those explanations apply to music, too, and I'm not interested in hearing about them there either if the reason for offering them is to help disabuse me of my love for good music. I know that people use the same word I use here to justify violence, self-interest, and hatred. I cannot help but feel angry and disgusted when it is used for those ends, ends which seem so contrary to what the word means for me, ends that make me think someone has read the wrong script, mis-cast the character, not known what deeds God has done.