Musonius

- This too is related to technology, of course. If the class is focused on video screens, then all the chairs will face the screens, and the classroom might even be structured like a theater. Etymologically, "theater" means something like "a place of gazing," and theaters tend to encourage people to gaze. Sometimes this can work against other activities, like colloquy, small-group interaction, and really anything that involves students moving from one place to another.

- If that last sentence made you ask,"But why do you want your students to move from one place to another?" then you see that we have some pretty strong presuppositions about how education should happen: students should sit and listen, teachers should stand and lecture. This communicates something about authority, and at times that's helpful. But it can also invite students to lean back into passivity, and to assume they have no role in their own education.

- The furniture in classrooms tells us how people are to behave, because it has been made and purchased by people who had in mind some idea of how students should behave. Most wrap-around desks are made for right-handed people, for instance. And most classroom desks I've seen expect students to sit upright, at attention, with a book open in front of them. I really don't like those desks, and I feel trapped when I sit in them. I wonder sometimes how they make my students feel. I wish we had fewer chairs and more sofas. Maybe a fireplace, or some tables with glasses of water, and ashtrays on them. I suppose I wish I could teach in pubs or ratskellers, which are, after all, places consciously designed for people to meet and discuss what most matters to them, informally, passionately, amicably.

- Classrooms that privilege video screens tend to undervalue natural light and windows. I am reminded of Emerson's reflection on a boring sermon he once heard. Emerson wrote, in his Divinity School Address, that while the minister droned on, Emerson looked out the window at the falling snow, which, he proclaimed, preached a better sermon than the minister. I have no doubt that nature can often give a better lecture than I can.

∞

What Are Philosophy's Flaws?

Last week I suggested to one of my students that she would make a good philosophy major. A few days later she came to my office and asked me, "What are philosophy's flaws?"

She wanted to know, she said, because she was thinking seriously about studying more philosophy, and for her, thinking seriously about something means considering something from all angles. She knows that ideas give birth to other ideas, and to practical consequences.

I don't think I gave her a very good answer at the time, but I've continued to think about it because it strikes me as a good question asked for a good reason.

Not long ago I was re-reading the Stoic philosopher Gaius Musonius Rufus. Of the four major Roman Stoics, he's probably the least well-known. Epictetus, Seneca and Marcus Aurelius all left substantial writings, but Musonius did not.

Rather, Musonius is known chiefly through the notes his students left behind. In fact, this is one of the reasons I like him so well: whatever became of his writings, his life made a difference for his students. His teaching mattered so much that they refused to let his life vanish from history.

There's another reason I like Musonius: he insisted that philosophy is for women, not just for men. Since the student whom I invited to study philosophy is also a woman, I want to try to give a better answer to her question by turning to Musonius now.

Once, when Musonius made the bold invitation for women to join the Stoic philosophers, someone asked him: won't studying philosophy make the women obstinate, independent, and opinionated?

He replied that in fact, it might do just that. Musonius recognized that the question was a question about the same thing my student was asking about: philosophy's flaws. Philosophy often makes us better thinkers, but it can also make us obnoxious to our neighbors when we care more about the ideas than about the people whose lives are connected to the ideas.

Musonius then quickly pointed out that the question is irrelevant, however, because what is true of women is also true of men in this regard. Like Augustine several centuries later, Musonius argued that women and men have equal intellectual powers. If philosophy entails the development and strengthening of our native intellect, then surely women will benefit from it just as much as men.

It would appear that the questioner wasn't concerned about people becoming opinionated, independent thinkers, but about women becoming opinionated, independent thinkers. What began as a question about the vices of philosophy quickly exposes itself as a question that reveals the bias of the questioner -- a bias that philosophy would be more than happy to correct.

This brings me to my student's question: Yes, philosophy has flaws, and one of its chief flaws is that when it is combined with a lack of kindness, it can amplify that unkindness.

But it also has the power to expose that unkindness in a pretty keen way. And when it is combined with kindness and positive regard for our neighbors -- with what we sometimes call agapé, or love -- it can be something that causes kindness to grow.

I don't mean that philosophy is a panacaea, or that it will do all good things for us, all on its unattended own.

But I do mean that you, my student, have very real native intelligence, and it pleases me to see it in you. And I would love to see it grow. To point to Augustine once more: Augustine found philosophy to be helpful for his own self-understanding, for his seeking after God, and for keeping his church from descending into irrationality. He regarded it as a way to "love God with his mind."

I wouldn't ask you, my student, to give up your nursing major. Quite the opposite! Just as surely as women need philosophy, I think nurses and business majors and scientists and poets need philosophy, too. I think that studying philosophy will make you a better nurse, one more able to improve the nursing profession and to improve your workplace.

And let me add one more thing. When you came into my office the other day to ask me that brilliant question, one thing was quite clear to me: whether or not you choose to make philosophy your formal major, you are already becoming a philosopher. And that makes me very happy indeed.

She wanted to know, she said, because she was thinking seriously about studying more philosophy, and for her, thinking seriously about something means considering something from all angles. She knows that ideas give birth to other ideas, and to practical consequences.

I don't think I gave her a very good answer at the time, but I've continued to think about it because it strikes me as a good question asked for a good reason.

Not long ago I was re-reading the Stoic philosopher Gaius Musonius Rufus. Of the four major Roman Stoics, he's probably the least well-known. Epictetus, Seneca and Marcus Aurelius all left substantial writings, but Musonius did not.

Rather, Musonius is known chiefly through the notes his students left behind. In fact, this is one of the reasons I like him so well: whatever became of his writings, his life made a difference for his students. His teaching mattered so much that they refused to let his life vanish from history.

There's another reason I like Musonius: he insisted that philosophy is for women, not just for men. Since the student whom I invited to study philosophy is also a woman, I want to try to give a better answer to her question by turning to Musonius now.

Once, when Musonius made the bold invitation for women to join the Stoic philosophers, someone asked him: won't studying philosophy make the women obstinate, independent, and opinionated?

He replied that in fact, it might do just that. Musonius recognized that the question was a question about the same thing my student was asking about: philosophy's flaws. Philosophy often makes us better thinkers, but it can also make us obnoxious to our neighbors when we care more about the ideas than about the people whose lives are connected to the ideas.

Musonius then quickly pointed out that the question is irrelevant, however, because what is true of women is also true of men in this regard. Like Augustine several centuries later, Musonius argued that women and men have equal intellectual powers. If philosophy entails the development and strengthening of our native intellect, then surely women will benefit from it just as much as men.

It would appear that the questioner wasn't concerned about people becoming opinionated, independent thinkers, but about women becoming opinionated, independent thinkers. What began as a question about the vices of philosophy quickly exposes itself as a question that reveals the bias of the questioner -- a bias that philosophy would be more than happy to correct.

This brings me to my student's question: Yes, philosophy has flaws, and one of its chief flaws is that when it is combined with a lack of kindness, it can amplify that unkindness.

But it also has the power to expose that unkindness in a pretty keen way. And when it is combined with kindness and positive regard for our neighbors -- with what we sometimes call agapé, or love -- it can be something that causes kindness to grow.

I don't mean that philosophy is a panacaea, or that it will do all good things for us, all on its unattended own.

But I do mean that you, my student, have very real native intelligence, and it pleases me to see it in you. And I would love to see it grow. To point to Augustine once more: Augustine found philosophy to be helpful for his own self-understanding, for his seeking after God, and for keeping his church from descending into irrationality. He regarded it as a way to "love God with his mind."

I wouldn't ask you, my student, to give up your nursing major. Quite the opposite! Just as surely as women need philosophy, I think nurses and business majors and scientists and poets need philosophy, too. I think that studying philosophy will make you a better nurse, one more able to improve the nursing profession and to improve your workplace.

And let me add one more thing. When you came into my office the other day to ask me that brilliant question, one thing was quite clear to me: whether or not you choose to make philosophy your formal major, you are already becoming a philosopher. And that makes me very happy indeed.

∞

As September approaches, people keep asking me, "Are you ready to get back in the classroom?"

As early as middle school I knew I wanted to become a college professor, and I love my job. It is a delight to spend time with young people who are curious, after all.

Years ago, my friend Matt Dickerson pointed out to me that it's also my job to help those who are not curious to see why they should be. As it turns out, that work is usually delightful, too, a rewarding challenge.

So on the whole, I love my work.

But I admit I don't love classrooms, for several reasons:

First, no matter what decade, every classroom I've been in has exhibited an unhealthy tendency towards becoming cluttered with the latest technology, and most of that tech seems to take up a lot of space and to become the center of attention. I'm not opposed to technology in the classroom, not at all. But I'm opposed to letting it get in the way, as it does when the "Smart Cart" leaves me no room for my lecture notes, or when I can't seem to turn the ceiling-mounted projector on or off. I'm a fan of chalk, because chalk allows spontaneity, and it allows for much more than alphanumeric writing in neat rows. Sadly, concerns about chalk dust getting into computers is threatening to make chalkboards disappear from my classrooms. Alas. Chalk is an excellent technology, and if it vanishes, I will mourn its loss.

Second, classroom architecture is not some value-free, neutral design. Classroom architecture makes a big difference in how people teach, and how they learn:

Which is why, as often as I can, I get my students out of the classroom. When we are reading Thoreau's Walking, we go for a walk. When I teach environmental philosophy, we often meet under the great tree in our campus quad, where I encourage students to daydream and to play with the grass, to look for worm-castings and owl pellets, feathers and seed-pods, invertebrates and fallen bits of bark. What good is it to gain the world of theoretical knowledge at the expense of knowledge gained through vital, haptic, bodily experience?

And this is why I am a preacher of the importance of study abroad. Not just travel, but serious, engaged, rigorous study in the classroom of life in another place. This is why I teach Classics in Greece every year, and why year after year I take students to Central America to study environmental philosophy and ecology.

More and more I've been trying to shift the learning focus in my classes from the classroom to the laboratory - where by "laboratory" I mean anywhere that allows students to learn with their whole person. I make my ancient philosophy students devote hours each semester to star-gazing, in part because this is what the ancients did, and in part because I don't want them to miss the stars. I want them to gaze in wonder at the firmament so that when they read Aristotle and Galileo they know that they've looked at what those great minds saw as well. We even occasionally take field trips to really dark places like the South Dakota Badlands so we can see the skies even better.

My environmental philosophy students must observe a square meter of earth for a semester, spending an hour at a time without a camera, drawing and writing about what they see, because it does not make sense to me to talk about the earth when you have not taken the time to sit upon it, to listen to it, to smell and taste it, and to see what other lives creep, and walk, and fly across it.

My friend Aage Jensen advocates the Norwegian philosophy of Friluftsliv, life and education outdoors. And when he organizes a conference on it, he eschews conference centers and holds the conference while walking through the mountains, or paddling a river. Because he believes that one should practice what one preaches, and that nature is always ready to teach.

To paraphrase the Stoic Musonius, teachers would do well to talk less and to take their students with them into the fields, because there they will learn far better and far more than in the lecture hall.

Teaching Outdoors

|

As early as middle school I knew I wanted to become a college professor, and I love my job. It is a delight to spend time with young people who are curious, after all.

Years ago, my friend Matt Dickerson pointed out to me that it's also my job to help those who are not curious to see why they should be. As it turns out, that work is usually delightful, too, a rewarding challenge.

So on the whole, I love my work.

But I admit I don't love classrooms, for several reasons:

First, no matter what decade, every classroom I've been in has exhibited an unhealthy tendency towards becoming cluttered with the latest technology, and most of that tech seems to take up a lot of space and to become the center of attention. I'm not opposed to technology in the classroom, not at all. But I'm opposed to letting it get in the way, as it does when the "Smart Cart" leaves me no room for my lecture notes, or when I can't seem to turn the ceiling-mounted projector on or off. I'm a fan of chalk, because chalk allows spontaneity, and it allows for much more than alphanumeric writing in neat rows. Sadly, concerns about chalk dust getting into computers is threatening to make chalkboards disappear from my classrooms. Alas. Chalk is an excellent technology, and if it vanishes, I will mourn its loss.

Second, classroom architecture is not some value-free, neutral design. Classroom architecture makes a big difference in how people teach, and how they learn:

|

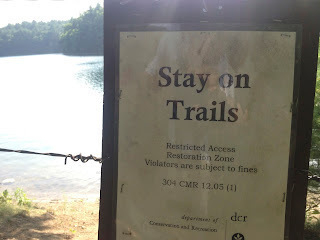

| Step off the trails! Explore! An ironic sign at Walden Pond. |

And this is why I am a preacher of the importance of study abroad. Not just travel, but serious, engaged, rigorous study in the classroom of life in another place. This is why I teach Classics in Greece every year, and why year after year I take students to Central America to study environmental philosophy and ecology.

More and more I've been trying to shift the learning focus in my classes from the classroom to the laboratory - where by "laboratory" I mean anywhere that allows students to learn with their whole person. I make my ancient philosophy students devote hours each semester to star-gazing, in part because this is what the ancients did, and in part because I don't want them to miss the stars. I want them to gaze in wonder at the firmament so that when they read Aristotle and Galileo they know that they've looked at what those great minds saw as well. We even occasionally take field trips to really dark places like the South Dakota Badlands so we can see the skies even better.

My environmental philosophy students must observe a square meter of earth for a semester, spending an hour at a time without a camera, drawing and writing about what they see, because it does not make sense to me to talk about the earth when you have not taken the time to sit upon it, to listen to it, to smell and taste it, and to see what other lives creep, and walk, and fly across it.

My friend Aage Jensen advocates the Norwegian philosophy of Friluftsliv, life and education outdoors. And when he organizes a conference on it, he eschews conference centers and holds the conference while walking through the mountains, or paddling a river. Because he believes that one should practice what one preaches, and that nature is always ready to teach.

To paraphrase the Stoic Musonius, teachers would do well to talk less and to take their students with them into the fields, because there they will learn far better and far more than in the lecture hall.

|

| Nature is full of things worth seeing. |