My favorite classrooms

∞

South Fork, Eagle River

After breakfast we put sack lunches in the cooler and threw our backpacks in the fifteen-passenger van. Half an hour later we were piling out at the state park on the South Fork of the Eagle River.

The houses here are ugly. Taken on their own, any one of them is a beautiful building. Plainly this is spendy real estate in God’s country. But the houses look like they were lifted from the pages of some little-boxes-full-of-ticky-tacky architectural lust propaganda and carpet-bombed on the hillside, then allowed to remain wherever they fell. There is no order, no sense that the houses were built for the place. Every one of them is a garish, angular excrescence on the opposite hillside. No doubt their inmates would disagree with my assessment; they only see the houses up close, and from the inside. They must have no idea how out of place their unnatural rectangles look against the sweeping slope of the Chugach Range. No doubt, when you’re on the other side of those big plates of glass, gazing over here at the state park over your morning K-cup, the view is precious. But when you’re in the state park, looking back, there is nothing on the opposite hillside to love. Over here, there is only regret that these people believed that you could buy both the land and the landscape.

It’s about three miles’ hike in to first bridge in state park. A fairly easy up-and-down walk. It’s raining. Spitting, really, what they call chipichipi in Guatemala, a constant drizzle. The sky is a palette of cottony grays that have lowered themselves onto the mountaintops. There is a clear line below which the mountains are visible. Above it, clouds roll and shift.

I shiver a little in my heavy raincoat and think about putting on my rain pants, but I know I’ll be too hot if I do. Some of my students are wearing shorts.

At the footbridge we sit and eat our lunches. The university has packed us red delicious apples (a mendacious name), bags of honey Dijon potato chips, and turkey sandwiches with lettuce and onions. It’s not good turkey, but no one cares. This is a lovely place. We have other food in this place.

The river is only fifteen feet wide here, and it is the color of chalk, like diluted Milk of Magnesia. Taking off my shoes, I wade in. Immediately my feet start to ache with cold. Turning over a stone, I look at its underside. The gray water drips off and a tiny larva wriggles to get out of the light. It's too small to identify it, maybe a miniscule stonefly. A huge blue dragonfly cruises over the river, darting past me.

There are lots of wildflowers up here. One of my students is on the ground with her laminated guidebook, puzzling over one specimen. I've been carrying these guides everywhere, but they're only helpful for about seventy-five percent of the common stuff. There's just too much life here to get it all in a book.

The flowers grow in so many colors, so many strategies for getting the scarce pollinators' attention in the brief summer. Yellows, purples, and blues predominate. The guidebook warns me about several of the purples: DO NOT EAT THIS! Some of them are poisonous. So are a few of the yellows. This is a beautiful place, but it's also a harsh place, and life clings to the edge. Poison is one good way not to get eaten, I suppose. Looking up the mountain, the trees give way to shrubs a hundred yards above us. A hundred yards more and there's only grass. Above that, I can only see rock.

Some of these plants have another strategy: rather than avoiding getting eaten, they invite it. Berries are the way some plants make use of animals to carry their seeds to new places. Bear scat, full of seeds, is all along the trails here. Each mound is a nursery where some new plant may grow in the fertile dung.

There is a kind of berry like a blueberry that grows on something that looks like a mix between evergreens and moss, only a few inches high. Some people call it "mossberry," appropriately. Some locals call it a blackberry. Matt tells us they're crowberries, as he gathers a handful. He eats some and then the students tentatively pick and eat some too.

We spend three hours there at the bridge, observing. There's so much to see. Some of us write, some draw, some stare at the peaks that surround us. A few doze off. I get out my watercolors and try to paint the landscape, but I'm quickly frustrated. There are so many greens and grays and blues, and I'm no good at mixing colors. I keep painting anyway. I can at least try to get the shapes right, I think, but I'm wrong about that, too. The mountains are stacked up in layers, and the lines look clean and clear at first, but when I try to focus on them they blur into one another. The hanging glacier at the end of the valley looms over us, silent and white and yet so eloquent. The glaciers are what made all of this, and even though they have retreated, the river runs with their tillage, the plants grow in their finely ground dust, the smooth slopes were ground smooth by millennia of ice.

Upstream, Brenden hooks his first-ever dolly varden. This is his first fish in Alaska. He is positively glowing with delight. He cradles it in his hand and then quickly returns it to the water pausing only to admire this vibrant glacial relic of a char. It too depends on the glacier.

The temperature is constantly shifting as the sun comes in and out of the clouds. Each part of the valley takes its turn being illuminated: the river shines like silver; the mountainside glows bright green and the rocks and bushes above the tree line cast sharp shadows; high in the valley small glaciers are bright ribbons streaking the blue granite. The clouds push the sunlight in ribbons across the valley. When we are suddenly in the light, we are warm.

After a few hours we walk back to the car. No one wants to go. For a while we drive in luminous silence.

The houses here are ugly. Taken on their own, any one of them is a beautiful building. Plainly this is spendy real estate in God’s country. But the houses look like they were lifted from the pages of some little-boxes-full-of-ticky-tacky architectural lust propaganda and carpet-bombed on the hillside, then allowed to remain wherever they fell. There is no order, no sense that the houses were built for the place. Every one of them is a garish, angular excrescence on the opposite hillside. No doubt their inmates would disagree with my assessment; they only see the houses up close, and from the inside. They must have no idea how out of place their unnatural rectangles look against the sweeping slope of the Chugach Range. No doubt, when you’re on the other side of those big plates of glass, gazing over here at the state park over your morning K-cup, the view is precious. But when you’re in the state park, looking back, there is nothing on the opposite hillside to love. Over here, there is only regret that these people believed that you could buy both the land and the landscape.

It’s about three miles’ hike in to first bridge in state park. A fairly easy up-and-down walk. It’s raining. Spitting, really, what they call chipichipi in Guatemala, a constant drizzle. The sky is a palette of cottony grays that have lowered themselves onto the mountaintops. There is a clear line below which the mountains are visible. Above it, clouds roll and shift.

I shiver a little in my heavy raincoat and think about putting on my rain pants, but I know I’ll be too hot if I do. Some of my students are wearing shorts.

At the footbridge we sit and eat our lunches. The university has packed us red delicious apples (a mendacious name), bags of honey Dijon potato chips, and turkey sandwiches with lettuce and onions. It’s not good turkey, but no one cares. This is a lovely place. We have other food in this place.

The river is only fifteen feet wide here, and it is the color of chalk, like diluted Milk of Magnesia. Taking off my shoes, I wade in. Immediately my feet start to ache with cold. Turning over a stone, I look at its underside. The gray water drips off and a tiny larva wriggles to get out of the light. It's too small to identify it, maybe a miniscule stonefly. A huge blue dragonfly cruises over the river, darting past me.

There are lots of wildflowers up here. One of my students is on the ground with her laminated guidebook, puzzling over one specimen. I've been carrying these guides everywhere, but they're only helpful for about seventy-five percent of the common stuff. There's just too much life here to get it all in a book.

The flowers grow in so many colors, so many strategies for getting the scarce pollinators' attention in the brief summer. Yellows, purples, and blues predominate. The guidebook warns me about several of the purples: DO NOT EAT THIS! Some of them are poisonous. So are a few of the yellows. This is a beautiful place, but it's also a harsh place, and life clings to the edge. Poison is one good way not to get eaten, I suppose. Looking up the mountain, the trees give way to shrubs a hundred yards above us. A hundred yards more and there's only grass. Above that, I can only see rock.

Some of these plants have another strategy: rather than avoiding getting eaten, they invite it. Berries are the way some plants make use of animals to carry their seeds to new places. Bear scat, full of seeds, is all along the trails here. Each mound is a nursery where some new plant may grow in the fertile dung.

There is a kind of berry like a blueberry that grows on something that looks like a mix between evergreens and moss, only a few inches high. Some people call it "mossberry," appropriately. Some locals call it a blackberry. Matt tells us they're crowberries, as he gathers a handful. He eats some and then the students tentatively pick and eat some too.

We spend three hours there at the bridge, observing. There's so much to see. Some of us write, some draw, some stare at the peaks that surround us. A few doze off. I get out my watercolors and try to paint the landscape, but I'm quickly frustrated. There are so many greens and grays and blues, and I'm no good at mixing colors. I keep painting anyway. I can at least try to get the shapes right, I think, but I'm wrong about that, too. The mountains are stacked up in layers, and the lines look clean and clear at first, but when I try to focus on them they blur into one another. The hanging glacier at the end of the valley looms over us, silent and white and yet so eloquent. The glaciers are what made all of this, and even though they have retreated, the river runs with their tillage, the plants grow in their finely ground dust, the smooth slopes were ground smooth by millennia of ice.

Upstream, Brenden hooks his first-ever dolly varden. This is his first fish in Alaska. He is positively glowing with delight. He cradles it in his hand and then quickly returns it to the water pausing only to admire this vibrant glacial relic of a char. It too depends on the glacier.

The temperature is constantly shifting as the sun comes in and out of the clouds. Each part of the valley takes its turn being illuminated: the river shines like silver; the mountainside glows bright green and the rocks and bushes above the tree line cast sharp shadows; high in the valley small glaciers are bright ribbons streaking the blue granite. The clouds push the sunlight in ribbons across the valley. When we are suddenly in the light, we are warm.

After a few hours we walk back to the car. No one wants to go. For a while we drive in luminous silence.

∞

Nature As A Classroom

For the last two weeks my students and I have been in Petén, Guatemala, studying the ecology of the region. For half that time we stayed with local families. Our homestays were arranged by the Asociación Bio-Itzá, an indigenous Maya conservation organization that runs a Spanish school to support their work in preserving a section of the Maya Biosphere Reserve. The other half of the time we spent on the reserve and hiking the Ruta Chiclera, a forty-mile trek through the Zotz and Tikal reserves, vast areas of largely unbroken subtropical forest.

These are not always easy conditions. Many hard-working Guatemalans live in poverty that is hard to conceive in our country; it is hot and wet except for when it is cold and wet; biting insects are everywhere; disease and snakes and thorny vines like bayal are constant threats.

But it is also a beautiful place with astonishing biodiversity and remarkable people whose resilience and generosity always make me want to improve my own character. They welcome us into their homes and into their lives, and they are glad to see us come to appreciate the place they live.

I expect that my students will forget much of what I say in my lectures and much of what they read in books. But I doubt very much that they will forget the people they have met here. Guatemala has gone from being an abstraction to a concrete reality. When they meet kind people of good character who have walked across Mexico and made it into the USA only to be caught and deported, "illegal immigrants" now have a face, a home, a family at whose table my students have received a nourishing and welcoming meal.

Likewise, they will not likely forget the sound of howler monkeys at night or the experience of scrambling up Maya temples still covered in a thousand years of trees and soil. They won't forget the long walk in a deep green forest and the smells of tortillas and beans cooked over a wood fire.

It is expensive to bring students so far. One could object that the money could be better spent on viewing the forest online or donating it to rainforest conservation. I disagree. I'm not in the business of dispensing information; I'm in the business of transforming lives, and not much transforms like full-bodied experience. Before we leave for Guatemala my students read papers written by wildlife conservation researchers. In Guatemala they meet those researchers in person and get to hear their stories. They hear in their tone and see in their eyes what brought them to Guatemala and what keeps them here. In such times my students go from taking in data to rethinking their lives.

It is my hope - my exuberant, perhaps not wholly rational hope - that out of such lived experience of nature my students will become people who comfort orphans and widows in their distress, who receive the foreigner into their own homes, who marvel and the world's diversity and who, for the rest of their lives, work to preserve it.

These are not always easy conditions. Many hard-working Guatemalans live in poverty that is hard to conceive in our country; it is hot and wet except for when it is cold and wet; biting insects are everywhere; disease and snakes and thorny vines like bayal are constant threats.

But it is also a beautiful place with astonishing biodiversity and remarkable people whose resilience and generosity always make me want to improve my own character. They welcome us into their homes and into their lives, and they are glad to see us come to appreciate the place they live.

I expect that my students will forget much of what I say in my lectures and much of what they read in books. But I doubt very much that they will forget the people they have met here. Guatemala has gone from being an abstraction to a concrete reality. When they meet kind people of good character who have walked across Mexico and made it into the USA only to be caught and deported, "illegal immigrants" now have a face, a home, a family at whose table my students have received a nourishing and welcoming meal.

Likewise, they will not likely forget the sound of howler monkeys at night or the experience of scrambling up Maya temples still covered in a thousand years of trees and soil. They won't forget the long walk in a deep green forest and the smells of tortillas and beans cooked over a wood fire.

It is expensive to bring students so far. One could object that the money could be better spent on viewing the forest online or donating it to rainforest conservation. I disagree. I'm not in the business of dispensing information; I'm in the business of transforming lives, and not much transforms like full-bodied experience. Before we leave for Guatemala my students read papers written by wildlife conservation researchers. In Guatemala they meet those researchers in person and get to hear their stories. They hear in their tone and see in their eyes what brought them to Guatemala and what keeps them here. In such times my students go from taking in data to rethinking their lives.

It is my hope - my exuberant, perhaps not wholly rational hope - that out of such lived experience of nature my students will become people who comfort orphans and widows in their distress, who receive the foreigner into their own homes, who marvel and the world's diversity and who, for the rest of their lives, work to preserve it.

∞

Camping With My Students: Stargazing in the Badlands

Around two in the morning I awoke to the song of coyotes. I opened my eyes and looked up just in time to see a green meteor arc across the sky. I was camping outdoors, with my students, in a remote corner of South Dakota. Welcome to one of my favorite classrooms.

Each fall I look for an ideal weekend to take my Ancient and Medieval Philosophy students stargazing. An ideal weekend counts as one where we will have clear skies, a new moon, and reasonably warm weather so we can spend a lot of time outside.

Several times over the last ten years, the weather's been so good that we've been able to go out to a primitive campground (i.e. one where there is no electricity and almost no urban glow) in the Badlands National Park.

On such nights, in such places, the sky glistens with stars. The Milky Way is a bright band across the night, and meteors punctuate our views each hour.

I tell my students that this is an optional trip. They don't get credit for coming, and they don't lose any credit for staying home. It's a four-hour drive from our campus, so it's a real commitment of time on their part. Their only rewards are these: an experience of what the Norwegians call friluftsliv, a beautiful night under the stars in a remote and lovely place, and free pancakes at sunrise, cooked by me.

And yet every time I offer this trip, half a dozen or more students - and sometimes other professors - tag along.

I've written before about the importance of teaching outdoors and of doing labs in philosophy. Experientia docet, experience teaches us. What we learn through lived, full-bodied experience tends to stick with us far better than what we simply hear spoken from a lectern or see on a PowerPoint slide.

We go out there, ostensibly, to see the stars. This is because I want my students to watch the skies and to imagine what it would have been like for ancient and medieval philosophers like Thales, Plutarch, Ptolemy, Eratosthenes and, even Galileo (on the cusp of the Middle Ages) to gaze at the skies and learn from their movements.

But we are really there for other reasons that are easier to show than to tell. I want them to see that ideas do not grow up in a vacuum, and that the artificial divisions between academic disciplines are really artificial and convenient. Educated people should care about all the disciplines. We should not allow them to be compartmentalized, as though philosophy and sociology had nothing to do with accounting, or physics, or poetry.

Aristotle tells us that the love of wisdom begins in wonder. I will add that experience of new things can be the beginning of wonder.

Many of my students have never heard coyotes sing. In the Badlands, they trot past our cots and tents and sing to us all night long. When we wake in the morning, we are often surrounded by small groups of bison, slowly grazing their way along the hillsides. After breakfast we climb the steep slopes and find ancient fossils.

I don't know if any of this is a desirable or assessable outcome for a philosophy class. Also, I don't care. Because all of these things are, I think, desirable outcomes for life.

Because I believe that "it is beautiful to do so" is reason enough to sleep under the stars.

|

| We set up tents, but we rarely use them. Much nicer to sleep under the stars. |

Each fall I look for an ideal weekend to take my Ancient and Medieval Philosophy students stargazing. An ideal weekend counts as one where we will have clear skies, a new moon, and reasonably warm weather so we can spend a lot of time outside.

Several times over the last ten years, the weather's been so good that we've been able to go out to a primitive campground (i.e. one where there is no electricity and almost no urban glow) in the Badlands National Park.

On such nights, in such places, the sky glistens with stars. The Milky Way is a bright band across the night, and meteors punctuate our views each hour.

I tell my students that this is an optional trip. They don't get credit for coming, and they don't lose any credit for staying home. It's a four-hour drive from our campus, so it's a real commitment of time on their part. Their only rewards are these: an experience of what the Norwegians call friluftsliv, a beautiful night under the stars in a remote and lovely place, and free pancakes at sunrise, cooked by me.

And yet every time I offer this trip, half a dozen or more students - and sometimes other professors - tag along.

|

| The stop sign is just a scratching post to this bison. |

I've written before about the importance of teaching outdoors and of doing labs in philosophy. Experientia docet, experience teaches us. What we learn through lived, full-bodied experience tends to stick with us far better than what we simply hear spoken from a lectern or see on a PowerPoint slide.

We go out there, ostensibly, to see the stars. This is because I want my students to watch the skies and to imagine what it would have been like for ancient and medieval philosophers like Thales, Plutarch, Ptolemy, Eratosthenes and, even Galileo (on the cusp of the Middle Ages) to gaze at the skies and learn from their movements.

But we are really there for other reasons that are easier to show than to tell. I want them to see that ideas do not grow up in a vacuum, and that the artificial divisions between academic disciplines are really artificial and convenient. Educated people should care about all the disciplines. We should not allow them to be compartmentalized, as though philosophy and sociology had nothing to do with accounting, or physics, or poetry.

Aristotle tells us that the love of wisdom begins in wonder. I will add that experience of new things can be the beginning of wonder.

Many of my students have never heard coyotes sing. In the Badlands, they trot past our cots and tents and sing to us all night long. When we wake in the morning, we are often surrounded by small groups of bison, slowly grazing their way along the hillsides. After breakfast we climb the steep slopes and find ancient fossils.

I don't know if any of this is a desirable or assessable outcome for a philosophy class. Also, I don't care. Because all of these things are, I think, desirable outcomes for life.

Because I believe that "it is beautiful to do so" is reason enough to sleep under the stars.

∞

The Howler Monkeys of Petén, Guatemala

Each year I co-teach a January-term class on tropical ecology in Guatemala and Belize.

One of my favorite experiences when I return to Guatemala is hearing the howler monkeys at night. Their voices travel for miles through the forest, it seems. My students are often alarmed by the noise, because the monkeys will approach silently and then begin to howl in the treetops overhead with voices that seem to belong to something much bigger than a mono aullador, as they are called in Spanish.

During one of my last trips I made this video. We were setting up camp in the Mayan Biosphere Reserve, or Biosfera Maya, en route to Tikal, when several troops of howlers began to sing nearby. We followed the voices to one of the nearest troops so we could get a closer look at these gentle beauties, our placid arboreal cousins. Enjoy the sound.

|

| One of the wonders of the Mayan Biosphere Reserve |

During one of my last trips I made this video. We were setting up camp in the Mayan Biosphere Reserve, or Biosfera Maya, en route to Tikal, when several troops of howlers began to sing nearby. We followed the voices to one of the nearest troops so we could get a closer look at these gentle beauties, our placid arboreal cousins. Enjoy the sound.

If you're interested in bringing your students to this fairly

well-preserved rainforest and arranging local guides, you might check

out the Asociación Bio-Itzá, an indigenous Mayan group dedicated to

preserving their forest, their ancestral knowledge, and their language.

They have a small rustic facility on their rainforest reserve and a

Spanish-language school for foreigners (with very reasonable prices) on the north shore of Lake Petén

Itzá, not far from the airport at Flores and from the beautiful ruins of

Tikal.

*****

(A friend tells me he extracted the sound from this video of mine and uploaded it to the wikipedia page on howler monkeys.)

∞

Writing, Law, and Memory in Ancient Gortyn

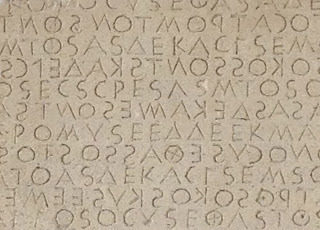

In the ruins of Gortyn, in central Crete, some of the famous ancient laws of Crete are preserved in stone. Archaeologists uncovered them in 1884, and have since built a brick enclosure to protect them from the weather.

Even though I'm not an expert in the Doric dialect, I love to read this inscription, for several reasons that might interest even those who don't know Greek.

First of all, it has an unusual alphabet, containing fewer letters than modern or classical Attic Greek. It lacks the vowels eta and omega (for which it uses epsilon and omicron), and the consonants zeta, xi, phi, chi, and psi (for which it substitutes other letters or combinations of other letters: two deltas for zeta, kappa+sigma for xi; pi for phi; kappa for chi; pi+sigma for psi.)

It also uses a letter that has since fallen out of use, the digamma. The digamma (or wau) is probably related to the Hebrew letter waw (or vav) and to the Roman letter F, which it closely resembles. By the classical age it had dropped out of use in Greek, and is fairly rare, like the letters sampi and qoppa.

(There is also a digamma in Delphi, not far from the Athena Pronaia sanctuary, on an upright stone dedicated to Athenai Warganai. That second word is related to the Greek word for "work" or "deed," ergon, and also to our word "work." This stone, pictured below, evinces several peculiarities of archaic Greek script. Look at the second word, which looks like it says FARCANAI. The first letter is digamma; the third letter, rho, very much resembles the Latin "R"; the letter immediately after it, gamma, looks like a flattened upper-case "C.")

Second, the writing is in boustrophedon style. Boustrophedon means something like "as the ox turns." Today we write in stoichedon style, in which all the letters face the same direction, like soldiers standing in formation. Boustrophedon is based on an agricultural, not a military ideal: the writer writes as a farmer plows. Write to the end of the line, and then, rather than returning to the left side of the page, turn the letters to face the opposite direction and write from right to left. When you read boustrophedon, your eye follows a zig-zag across the page -- or the stone.

Have a look at this close-up of the engraving at Gortys and look at the way letters like "E," "K," and "S" face in adjacent lines:

(By the way, that "S" character is actually an iota; sigmas look like this: M; mu is like our "M" with an extra stroke added.)

There are a lot of other reasons to like this place, and this inscription, but I'll limit myself to just one more thing for now: memory.

This inscription is one way that an ancient community deliberately remembered their laws. They wrote down what they decided, and that has affected our lives. Writing the law down makes it accessible to everyone, and makes judicial decisions transparent. It establishes a set of expectations for conduct in the community, and makes those expectations known even to aliens.

The code at Gortyn records (in Column IX, around the middle, if you're curious) the presence at court of someone in addition to the judge: the mnemon. You can see by the word's resemblance to our word "mnemonic" that it has to do with memory. The mnemon's job was to act as a witness to previous judicial decisions, and to remember them and remind the judge of those decisions. The mnemon's job was not to decide cases but to be a kind of embodiment of the law and therefore an embodiment of fairness.

Unfortunately, no mnemon lives forever. Presumably, the writing on the wall at Gortyn was a way of preserving what mattered most in the court, so that when they passed away, their memories would live on through the ages.

*****

Harold Fowler writes in a footnote to his 1921 translation of the Cratylus that under Eucleides the Athenians officially changed their alphabet from the archaic one to the Ionian alphabet in 404/403 BCE. This expanded their system of vowels, adding the long vowels eta and omega. It became known as the Euclidean Alphabet.

*****

If you can find it, Adonis Vasilakis' The Great Inscription of the Law Code of Gortyn (Heraklion/Iraklio: Mystis O.E.) is a great resource. It has a facsimile of the whole wall, a complete translation, and some helpful historical observations. ISBN 9608853400

|

| Gortyn, Crete |

Even though I'm not an expert in the Doric dialect, I love to read this inscription, for several reasons that might interest even those who don't know Greek.

First of all, it has an unusual alphabet, containing fewer letters than modern or classical Attic Greek. It lacks the vowels eta and omega (for which it uses epsilon and omicron), and the consonants zeta, xi, phi, chi, and psi (for which it substitutes other letters or combinations of other letters: two deltas for zeta, kappa+sigma for xi; pi for phi; kappa for chi; pi+sigma for psi.)

It also uses a letter that has since fallen out of use, the digamma. The digamma (or wau) is probably related to the Hebrew letter waw (or vav) and to the Roman letter F, which it closely resembles. By the classical age it had dropped out of use in Greek, and is fairly rare, like the letters sampi and qoppa.

(There is also a digamma in Delphi, not far from the Athena Pronaia sanctuary, on an upright stone dedicated to Athenai Warganai. That second word is related to the Greek word for "work" or "deed," ergon, and also to our word "work." This stone, pictured below, evinces several peculiarities of archaic Greek script. Look at the second word, which looks like it says FARCANAI. The first letter is digamma; the third letter, rho, very much resembles the Latin "R"; the letter immediately after it, gamma, looks like a flattened upper-case "C.")

|

|

"Athenai Warganai" inscription at Delphi

|

Second, the writing is in boustrophedon style. Boustrophedon means something like "as the ox turns." Today we write in stoichedon style, in which all the letters face the same direction, like soldiers standing in formation. Boustrophedon is based on an agricultural, not a military ideal: the writer writes as a farmer plows. Write to the end of the line, and then, rather than returning to the left side of the page, turn the letters to face the opposite direction and write from right to left. When you read boustrophedon, your eye follows a zig-zag across the page -- or the stone.

Have a look at this close-up of the engraving at Gortys and look at the way letters like "E," "K," and "S" face in adjacent lines:

|

| Close-up of the Gortyn Code |

There are a lot of other reasons to like this place, and this inscription, but I'll limit myself to just one more thing for now: memory.

This inscription is one way that an ancient community deliberately remembered their laws. They wrote down what they decided, and that has affected our lives. Writing the law down makes it accessible to everyone, and makes judicial decisions transparent. It establishes a set of expectations for conduct in the community, and makes those expectations known even to aliens.

The code at Gortyn records (in Column IX, around the middle, if you're curious) the presence at court of someone in addition to the judge: the mnemon. You can see by the word's resemblance to our word "mnemonic" that it has to do with memory. The mnemon's job was to act as a witness to previous judicial decisions, and to remember them and remind the judge of those decisions. The mnemon's job was not to decide cases but to be a kind of embodiment of the law and therefore an embodiment of fairness.

Unfortunately, no mnemon lives forever. Presumably, the writing on the wall at Gortyn was a way of preserving what mattered most in the court, so that when they passed away, their memories would live on through the ages.

|

| National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Possibly a child's dish? The sixth letter is digamma. |

*****

Harold Fowler writes in a footnote to his 1921 translation of the Cratylus that under Eucleides the Athenians officially changed their alphabet from the archaic one to the Ionian alphabet in 404/403 BCE. This expanded their system of vowels, adding the long vowels eta and omega. It became known as the Euclidean Alphabet.

*****

If you can find it, Adonis Vasilakis' The Great Inscription of the Law Code of Gortyn (Heraklion/Iraklio: Mystis O.E.) is a great resource. It has a facsimile of the whole wall, a complete translation, and some helpful historical observations. ISBN 9608853400

∞

On Traveling and Journaling

It's been too long since I've blogged. My excuse? I've been traveling a lot, including quite a bit with students. In the last few months I've been in Belize, Guatemala, Greece, and the UK with my students.

This probably sounds like a dream life, and I have to admit it's not all that bad.

But it's also a lot of work. A weeklong class in Greece usually takes me a little over a year to prepare, and in the semester leading up to it the workload approaches the amount of preparation I do for any of my other classes. Last fall I was teaching my usual load plus prepping two study-abroad courses, so I was swamped much of the time.

But it's worth it. My students come back with perspectives they could not have gained at home, if their journals are to be believed.

I always require my students to keep a journal while we're traveling. Sometimes I ask them specific questions, but usually I tell them to journal not for me but for themselves. You may think this naive, and you may be right. But I'd rather be naive than cynical. That is, I'd rather appeal to their self-interest and to their own sense of themselves as growing learners than force them to write answers to my pre-fab questions.

I do give them some guidance, however. Here are some of the things I teach them about journaling:

1) Pay attention to the little things, and write down whatever catches your attention. If you noticed it, it probably matters.

2) Pay attention to all of your senses. We tend to write about major events that happened, as though we were news reporters looking for the big story. But why not write about the smells? What sounds do you hear? What do the birds or the streets or the nighttimes sound like? How does the place you're in feel on your skin? What new tastes have you encountered? And so on.

3) Write continuously. Don't plan to write a sketch or outline and then fill it in later. As soon as you are on that plane home you will begin to forget what you experienced, and you will forget far more quickly than you want to believe. Write now.

4) Write "gestures" and impressions. Some of us have very good prose composition skills, and some of us do not. But all of us can write down a few phrases, a few adjectives, a few words we've heard in passing. Why not include entries in which you stand in one place and write down a list of nouns, of verbs, of adjectives that strike you as you soak the place in?

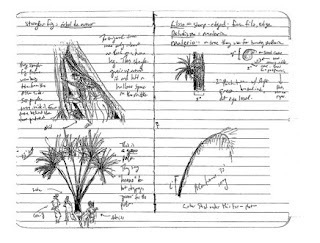

5) Draw pictures. This is one of the best pieces of advice I've ever received, and I am no artist. Cameras are great, but they capture what they see. Drawing captures what you see. Drawing also forces you to see what you wouldn't have seen otherwise. As Louis Agassiz once said, a pencil is one of the best tools for seeing. One of the best drawing tools I know of is a cheap ball-point pen. You don't need fancy paper, and you don't need a lot of time. Most of my best journal drawings are made in under two minutes with a cheap pen.

Try this out, and see if it doesn't completely change your journals. When I'm in Greece, I like to show my students the different kinds of stonework in ancient walls. The kind of stonework is helpful for dating the site, and it tells us a lot about the technology of the people who built the walls. I've found that as I try to draw a section of wall, the differences between cyclopean walls, Lesbian walls, and Roman walls become clearer to me, I remember them better, and I am better able to teach about them.

6) Revisit your journal periodically. Last of all, when you get back, revisit your journal from time to time. Start off doing so every week, and then every month and every year. When you revisit it, add a page or two of notes. What does your experience traveling back then mean to you now? Traveling is a luxury some of us enjoy, but it can also be a valuable learning opportunity, one that continues to be valuable for as long as we continue to reflect on it.

Do you have other journaling tips? I'd love to hear them. Meanwhile, I've got to get back to preparing for my next trips and courses abroad.

Buen viaje!

This probably sounds like a dream life, and I have to admit it's not all that bad.

But it's also a lot of work. A weeklong class in Greece usually takes me a little over a year to prepare, and in the semester leading up to it the workload approaches the amount of preparation I do for any of my other classes. Last fall I was teaching my usual load plus prepping two study-abroad courses, so I was swamped much of the time.

But it's worth it. My students come back with perspectives they could not have gained at home, if their journals are to be believed.

I always require my students to keep a journal while we're traveling. Sometimes I ask them specific questions, but usually I tell them to journal not for me but for themselves. You may think this naive, and you may be right. But I'd rather be naive than cynical. That is, I'd rather appeal to their self-interest and to their own sense of themselves as growing learners than force them to write answers to my pre-fab questions.

I do give them some guidance, however. Here are some of the things I teach them about journaling:

1) Pay attention to the little things, and write down whatever catches your attention. If you noticed it, it probably matters.

2) Pay attention to all of your senses. We tend to write about major events that happened, as though we were news reporters looking for the big story. But why not write about the smells? What sounds do you hear? What do the birds or the streets or the nighttimes sound like? How does the place you're in feel on your skin? What new tastes have you encountered? And so on.

3) Write continuously. Don't plan to write a sketch or outline and then fill it in later. As soon as you are on that plane home you will begin to forget what you experienced, and you will forget far more quickly than you want to believe. Write now.

4) Write "gestures" and impressions. Some of us have very good prose composition skills, and some of us do not. But all of us can write down a few phrases, a few adjectives, a few words we've heard in passing. Why not include entries in which you stand in one place and write down a list of nouns, of verbs, of adjectives that strike you as you soak the place in?

5) Draw pictures. This is one of the best pieces of advice I've ever received, and I am no artist. Cameras are great, but they capture what they see. Drawing captures what you see. Drawing also forces you to see what you wouldn't have seen otherwise. As Louis Agassiz once said, a pencil is one of the best tools for seeing. One of the best drawing tools I know of is a cheap ball-point pen. You don't need fancy paper, and you don't need a lot of time. Most of my best journal drawings are made in under two minutes with a cheap pen.

Try this out, and see if it doesn't completely change your journals. When I'm in Greece, I like to show my students the different kinds of stonework in ancient walls. The kind of stonework is helpful for dating the site, and it tells us a lot about the technology of the people who built the walls. I've found that as I try to draw a section of wall, the differences between cyclopean walls, Lesbian walls, and Roman walls become clearer to me, I remember them better, and I am better able to teach about them.

6) Revisit your journal periodically. Last of all, when you get back, revisit your journal from time to time. Start off doing so every week, and then every month and every year. When you revisit it, add a page or two of notes. What does your experience traveling back then mean to you now? Traveling is a luxury some of us enjoy, but it can also be a valuable learning opportunity, one that continues to be valuable for as long as we continue to reflect on it.

Do you have other journaling tips? I'd love to hear them. Meanwhile, I've got to get back to preparing for my next trips and courses abroad.

Buen viaje!

∞

Learn Spanish in Guatemala, Help Save the Rainforest

Immersive Spanish language learning in Guatemala’s Asociación Bio-Itzá supports cultural preservation and sustainable community development efforts.

∞

When I was preparing to go to grad school I was torn between two choices: Ph.D. in marine/riparian biology, or Ph.D. in philosophy? I love fish, aquatic invertebrates,

(well, most of them, anyway) and the environments they live in. Wouldn't it be great to make freestone streams and tidal pools into my classrooms?

But I also love philosophy. Philosophy has connections to every other discipline; it offers a unique perspective on human activities; and it promotes some of the most interesting and fruitful conversations I know of. (Yes, I admit some professional bias here, and don't begrudge others a similar bias towards what they love.) Philosophy classes take on questions about truth, value, meaning, religion, justice, science, language, reason, history, relationships, and much more. It can be very difficult, but there's usually a huge payoff for the effort you put into it.

Now that I teach philosophy, I often find myself lurking around the biology department at my school, to read their journals, to talk with the professors there (who patiently put up with my presence there), and to eye their labs with envy.

Now, I think bio labs are great places, but it's not the places themselves that I most like. It's rather the idea of the place. Labs are spaces set apart for learning by experience. We have labs for the sciences, and we have labs for the arts as well (though we usually call those "studios"). In the social sciences they use labs for observing human activities, and foreign languages have (or ought to have) labs for practicing language. Writers have workshops, historians have museums and archives, and other disciplines have internships.

Philosophy, unlike all these other disciplines, does not appear to have any labs at all. At least, not at first glance.

Partly this is due to the reflective nature of philosophy: philosophers have often understood our discipline as a step back from experience in order to gain a cool, disinterested view of the world. To some degree, we still think that, but that idea of having a privileged access to reality through the use of the right kind of language, or through a scientific worldview, has fallen under suspicion. Pace Descartes, we don't necessarily understand the world better by turning completely away from it.

Contrary to popular opinion, "philosophy" is not a synonym for "opinion." Nor is it a synonym for "doctrines." Philosophy has grown and changed quite a lot in the last few centuries, which means that is not always easy to define. One thing that is common to all philosophers, however, is that philosophy is an activity. Doing philosophy is not the mere rehearsal of past views, nor is it merely an attempt to present our already established opinions in clearer or more persuasive language.

Philosophers do, in fact, set aside spaces and times for practicing philosophy. One important kind of lab philosophers have is the seminar, which has its roots in Plato's practice of philosophy. Whatever else we might say about Plato, he knew how important good conversation is to advancing philosophy. In his dialogues, Plato uses conversation to illustrate two points: first, we need to spend at least some of our time in serious, sustained conversation and reflection with others. Second, when we do so, we need to follow the argument where it leads and not just where we want it to go.

In future posts I'll take up several other kinds of "labs" philosophers use, which I'll mention briefly here. First, recently, some philosophers have begun doing what they call "experimental philosophy." Second, I find that teaching philosophy "in the field" (for environmental philosophy or ethics, for instance) or teaching abroad provides a special experience for animating philosophical conversations. Third, I've come up with several "hands-on" (or, just as often, "eyes-on") projects for my classes in Ancient and Medieval Philosophy and Environmental Philosophy that are helpful pedagogical tools.

*********************

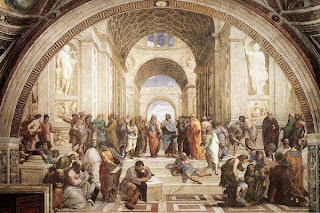

[Images: Raphael's "School of Athens," showing famous Greek philosophers "at work"; two mayflies photgraphed in the summer of 2009 in Gravenhurst, Ontario; one of the tributaries to Lake Muskoka in Ontario; a brook trout photographed on the Magalloway River in Maine, 2009 while fishing and doing some research with Matt Dickerson. The Raphael image is in the public domain; the others are my own photos. I think mayflies are especially lovely creatures. The adult stage shown above is a very brief period of their lives; most of their lives are spent underwater, and their appearance is quite different then from what it is as adults.]

Do Philosophy Classes Have "Labs"?

When I was preparing to go to grad school I was torn between two choices: Ph.D. in marine/riparian biology, or Ph.D. in philosophy? I love fish, aquatic invertebrates,

(well, most of them, anyway) and the environments they live in. Wouldn't it be great to make freestone streams and tidal pools into my classrooms?

But I also love philosophy. Philosophy has connections to every other discipline; it offers a unique perspective on human activities; and it promotes some of the most interesting and fruitful conversations I know of. (Yes, I admit some professional bias here, and don't begrudge others a similar bias towards what they love.) Philosophy classes take on questions about truth, value, meaning, religion, justice, science, language, reason, history, relationships, and much more. It can be very difficult, but there's usually a huge payoff for the effort you put into it.

Now that I teach philosophy, I often find myself lurking around the biology department at my school, to read their journals, to talk with the professors there (who patiently put up with my presence there), and to eye their labs with envy.

Now, I think bio labs are great places, but it's not the places themselves that I most like. It's rather the idea of the place. Labs are spaces set apart for learning by experience. We have labs for the sciences, and we have labs for the arts as well (though we usually call those "studios"). In the social sciences they use labs for observing human activities, and foreign languages have (or ought to have) labs for practicing language. Writers have workshops, historians have museums and archives, and other disciplines have internships.

Philosophy, unlike all these other disciplines, does not appear to have any labs at all. At least, not at first glance.

Partly this is due to the reflective nature of philosophy: philosophers have often understood our discipline as a step back from experience in order to gain a cool, disinterested view of the world. To some degree, we still think that, but that idea of having a privileged access to reality through the use of the right kind of language, or through a scientific worldview, has fallen under suspicion. Pace Descartes, we don't necessarily understand the world better by turning completely away from it.

Contrary to popular opinion, "philosophy" is not a synonym for "opinion." Nor is it a synonym for "doctrines." Philosophy has grown and changed quite a lot in the last few centuries, which means that is not always easy to define. One thing that is common to all philosophers, however, is that philosophy is an activity. Doing philosophy is not the mere rehearsal of past views, nor is it merely an attempt to present our already established opinions in clearer or more persuasive language.

Philosophers do, in fact, set aside spaces and times for practicing philosophy. One important kind of lab philosophers have is the seminar, which has its roots in Plato's practice of philosophy. Whatever else we might say about Plato, he knew how important good conversation is to advancing philosophy. In his dialogues, Plato uses conversation to illustrate two points: first, we need to spend at least some of our time in serious, sustained conversation and reflection with others. Second, when we do so, we need to follow the argument where it leads and not just where we want it to go.

|

| A brook trout I photographed in Maine. |

*********************

[Images: Raphael's "School of Athens," showing famous Greek philosophers "at work"; two mayflies photgraphed in the summer of 2009 in Gravenhurst, Ontario; one of the tributaries to Lake Muskoka in Ontario; a brook trout photographed on the Magalloway River in Maine, 2009 while fishing and doing some research with Matt Dickerson. The Raphael image is in the public domain; the others are my own photos. I think mayflies are especially lovely creatures. The adult stage shown above is a very brief period of their lives; most of their lives are spent underwater, and their appearance is quite different then from what it is as adults.]

∞

This year I am playing around with Google Wave's map feature and wondering if I can use Wave to help prepare my students to make the most of our limited time in Greece.

Do you have suggestions for how I can use this for my course? Are you also new to Wave and interested in Greece? If so, send me a wave at dr.dlohara@googlewave.com and I'll include you in my "sandbox" where I'm playing around with the possibilities.

(Photo credit: Dr. Jeffrey A. Johnson, Providence College)

Google Wave and My Course in Greece

Each year I teach a course in Greece, and I require my students to make presentations at a variety of archaeological and cultural sites.

This year I am playing around with Google Wave's map feature and wondering if I can use Wave to help prepare my students to make the most of our limited time in Greece.

Do you have suggestions for how I can use this for my course? Are you also new to Wave and interested in Greece? If so, send me a wave at dr.dlohara@googlewave.com and I'll include you in my "sandbox" where I'm playing around with the possibilities.

(Photo credit: Dr. Jeffrey A. Johnson, Providence College)

∞

Russell Frank and the 4/40 Program

One semester when I was in grad school at Penn State I was assigned to teach a course called "Media Ethics." I had no idea how to teach such a course, so I called up Dr. Russell Frank to ask him for a textbook recommendation.

Frank wrote a weekly column for the Centre Daily Times. At the time, he was an untenured professor in the Department of Communications at Penn State. Even though he did not know me, and surely had many demands on his time, Frank offered to meet me for coffee.

We met for three hours that day, during which I took pages of notes and basically wrote my syllabus for the course. He also gave me a stack of textbooks from his office, offered to guest-lecture in my class (which he later did, several times) and then, to top it all off, he paid for the coffee.

I protested that I was getting all the benefit from this and that I should pay. He replied, "My rule is this: the student never pays." Instead of paying him back, he said, I could "pay it forward" to some of my students.

So I began what I now call The 4/40 program. Whenever I meet students for a meal or coffee, I explain this to them: during their four years of undergraduate study with me (and if they visit me while they're in grad school) I pay. If they want, then they can visit me sometime in the next forty years and take me out for a meal or, better yet, they can use the next forty years to take someone else out for a meal.

I find these meals are always worthwhile. Much of the best learning in college happens outside the classroom, in informal conversations, often while breaking bread together. I teach because I love teaching, and these meals or coffees have provided me with some of my favorite classrooms: coffee shops, restaurants, the dining room table or kitchen in our home.

So to any of my students who may be reading this: don't thank me, thank Russell Frank (you can find his email at the link above or right here if you want). And if you benefited from the coffee, or the meal, pay it forward to someone else.

And come back and visit sometime.

Frank wrote a weekly column for the Centre Daily Times. At the time, he was an untenured professor in the Department of Communications at Penn State. Even though he did not know me, and surely had many demands on his time, Frank offered to meet me for coffee.

We met for three hours that day, during which I took pages of notes and basically wrote my syllabus for the course. He also gave me a stack of textbooks from his office, offered to guest-lecture in my class (which he later did, several times) and then, to top it all off, he paid for the coffee.

I protested that I was getting all the benefit from this and that I should pay. He replied, "My rule is this: the student never pays." Instead of paying him back, he said, I could "pay it forward" to some of my students.

So I began what I now call The 4/40 program. Whenever I meet students for a meal or coffee, I explain this to them: during their four years of undergraduate study with me (and if they visit me while they're in grad school) I pay. If they want, then they can visit me sometime in the next forty years and take me out for a meal or, better yet, they can use the next forty years to take someone else out for a meal.

I find these meals are always worthwhile. Much of the best learning in college happens outside the classroom, in informal conversations, often while breaking bread together. I teach because I love teaching, and these meals or coffees have provided me with some of my favorite classrooms: coffee shops, restaurants, the dining room table or kitchen in our home.

So to any of my students who may be reading this: don't thank me, thank Russell Frank (you can find his email at the link above or right here if you want). And if you benefited from the coffee, or the meal, pay it forward to someone else.

And come back and visit sometime.