pedagogy

- This too is related to technology, of course. If the class is focused on video screens, then all the chairs will face the screens, and the classroom might even be structured like a theater. Etymologically, "theater" means something like "a place of gazing," and theaters tend to encourage people to gaze. Sometimes this can work against other activities, like colloquy, small-group interaction, and really anything that involves students moving from one place to another.

- If that last sentence made you ask,"But why do you want your students to move from one place to another?" then you see that we have some pretty strong presuppositions about how education should happen: students should sit and listen, teachers should stand and lecture. This communicates something about authority, and at times that's helpful. But it can also invite students to lean back into passivity, and to assume they have no role in their own education.

- The furniture in classrooms tells us how people are to behave, because it has been made and purchased by people who had in mind some idea of how students should behave. Most wrap-around desks are made for right-handed people, for instance. And most classroom desks I've seen expect students to sit upright, at attention, with a book open in front of them. I really don't like those desks, and I feel trapped when I sit in them. I wonder sometimes how they make my students feel. I wish we had fewer chairs and more sofas. Maybe a fireplace, or some tables with glasses of water, and ashtrays on them. I suppose I wish I could teach in pubs or ratskellers, which are, after all, places consciously designed for people to meet and discuss what most matters to them, informally, passionately, amicably.

- Classrooms that privilege video screens tend to undervalue natural light and windows. I am reminded of Emerson's reflection on a boring sermon he once heard. Emerson wrote, in his Divinity School Address, that while the minister droned on, Emerson looked out the window at the falling snow, which, he proclaimed, preached a better sermon than the minister. I have no doubt that nature can often give a better lecture than I can.

∞

SPUnK: The Society for the Preservation of Unnecessary Knowledge

My brilliant and curious student James Jennings was interviewed by the brilliant and curious Hugh Weber on South Dakota Public Broadcasting's Dakota Midday.

James is a Philosophy and Classics major at Augustana University, and he's also the Prime Minister of SPUnK, a campus group I advise at Augustana University.

SPUnK - the Society for the Preservation of Unnecessary Knowledge - is devoted to learning about things we don't need to learn about, because we think unnecessary knowledge is worth preserving and promoting. We distinguish between those things students are told they must study in order to get a job, and those things that we study because there is delight in wonder, and in learning new things, even if we don't yet see their practical use. As both Plato's Socrates and Aristotle pointed out, the love of wisdom begins in wonder, and we seek knowledge not for some simple or material gain but for the satisfaction of wonder and out of a desire to know. Here's Aristotle:

This is what SPUnK is all about.

James and Hugh will teach you about paper towns, curiosity, education, Abraham Flexner, Albert Einstein, Rubik's Cubes, and other unnecessary knowledge. It's a short interview, well worth a few minutes of your time. Unnecessary knowledge is worth quite a lot more than a little of our time, after all.

* For two places Plato and Aristotle say this, see Plato's Theaetetus 155b and Aristotle's Metaphysics 982b.)

** Peirce writes about this in the first chapter of Justus Buchler's The Philosophical Writings of Peirce.

James is a Philosophy and Classics major at Augustana University, and he's also the Prime Minister of SPUnK, a campus group I advise at Augustana University.

SPUnK - the Society for the Preservation of Unnecessary Knowledge - is devoted to learning about things we don't need to learn about, because we think unnecessary knowledge is worth preserving and promoting. We distinguish between those things students are told they must study in order to get a job, and those things that we study because there is delight in wonder, and in learning new things, even if we don't yet see their practical use. As both Plato's Socrates and Aristotle pointed out, the love of wisdom begins in wonder, and we seek knowledge not for some simple or material gain but for the satisfaction of wonder and out of a desire to know. Here's Aristotle:

"Now he who wonders and is perplexed feels that he is ignorant (thus the myth-lover is in a sense a philosopher, since myths are composed of wonders); therefore if it was to escape ignorance that men studied philosophy, it is obvious that they pursued science for the sake of knowledge, and not for any practical utility.The actual course of events bears witness to this; for speculation of this kind began with a view to recreation and pastime, at a time when practically all the necessities of life were already supplied. Clearly then it is for no extrinsic advantage that we seek this knowledge; for just as we call a man independent who exists for himself and not for another, so we call this the only independent science, since it alone exists for itself."*Or, as Charles Peirce once put it, science is the practice of those who desire to find things out.**

This is what SPUnK is all about.

James and Hugh will teach you about paper towns, curiosity, education, Abraham Flexner, Albert Einstein, Rubik's Cubes, and other unnecessary knowledge. It's a short interview, well worth a few minutes of your time. Unnecessary knowledge is worth quite a lot more than a little of our time, after all.

*****

* For two places Plato and Aristotle say this, see Plato's Theaetetus 155b and Aristotle's Metaphysics 982b.)

** Peirce writes about this in the first chapter of Justus Buchler's The Philosophical Writings of Peirce.

∞

Good Education Should Lead To Good Questions

"If we treat the contemplation of the best life as a luxury we cannot

afford, seemingly urgent matters will crowd out the truly important

ones."

[....]

"If the aim of education is to gain money and power, where can we turn for help in knowing what to do with that money and power? Only a disordered mind thinks that these are ends in themselves. Socrates offers us the cautionary tale of the athlete-physician Herodicus, who wins fame and money through his athletic prowess and medicine, then proceeds to spend all his wealth trying to preserve his youth. This is what we mean by a disordered mind. He has been trained in the STEM fields of his time, and his training gains him great wealth, but it leaves him foolish enough to spend it all on something he can never buy."

[....]

"If the aim of education is to gain money and power, where can we turn for help in knowing what to do with that money and power? Only a disordered mind thinks that these are ends in themselves. Socrates offers us the cautionary tale of the athlete-physician Herodicus, who wins fame and money through his athletic prowess and medicine, then proceeds to spend all his wealth trying to preserve his youth. This is what we mean by a disordered mind. He has been trained in the STEM fields of his time, and his training gains him great wealth, but it leaves him foolish enough to spend it all on something he can never buy."

From my latest article, co-authored with John Kaag, in The Chronicle of Higher Education. Read it all here.

∞

Nature As A Classroom

For the last two weeks my students and I have been in Petén, Guatemala, studying the ecology of the region. For half that time we stayed with local families. Our homestays were arranged by the Asociación Bio-Itzá, an indigenous Maya conservation organization that runs a Spanish school to support their work in preserving a section of the Maya Biosphere Reserve. The other half of the time we spent on the reserve and hiking the Ruta Chiclera, a forty-mile trek through the Zotz and Tikal reserves, vast areas of largely unbroken subtropical forest.

These are not always easy conditions. Many hard-working Guatemalans live in poverty that is hard to conceive in our country; it is hot and wet except for when it is cold and wet; biting insects are everywhere; disease and snakes and thorny vines like bayal are constant threats.

But it is also a beautiful place with astonishing biodiversity and remarkable people whose resilience and generosity always make me want to improve my own character. They welcome us into their homes and into their lives, and they are glad to see us come to appreciate the place they live.

I expect that my students will forget much of what I say in my lectures and much of what they read in books. But I doubt very much that they will forget the people they have met here. Guatemala has gone from being an abstraction to a concrete reality. When they meet kind people of good character who have walked across Mexico and made it into the USA only to be caught and deported, "illegal immigrants" now have a face, a home, a family at whose table my students have received a nourishing and welcoming meal.

Likewise, they will not likely forget the sound of howler monkeys at night or the experience of scrambling up Maya temples still covered in a thousand years of trees and soil. They won't forget the long walk in a deep green forest and the smells of tortillas and beans cooked over a wood fire.

It is expensive to bring students so far. One could object that the money could be better spent on viewing the forest online or donating it to rainforest conservation. I disagree. I'm not in the business of dispensing information; I'm in the business of transforming lives, and not much transforms like full-bodied experience. Before we leave for Guatemala my students read papers written by wildlife conservation researchers. In Guatemala they meet those researchers in person and get to hear their stories. They hear in their tone and see in their eyes what brought them to Guatemala and what keeps them here. In such times my students go from taking in data to rethinking their lives.

It is my hope - my exuberant, perhaps not wholly rational hope - that out of such lived experience of nature my students will become people who comfort orphans and widows in their distress, who receive the foreigner into their own homes, who marvel and the world's diversity and who, for the rest of their lives, work to preserve it.

These are not always easy conditions. Many hard-working Guatemalans live in poverty that is hard to conceive in our country; it is hot and wet except for when it is cold and wet; biting insects are everywhere; disease and snakes and thorny vines like bayal are constant threats.

But it is also a beautiful place with astonishing biodiversity and remarkable people whose resilience and generosity always make me want to improve my own character. They welcome us into their homes and into their lives, and they are glad to see us come to appreciate the place they live.

I expect that my students will forget much of what I say in my lectures and much of what they read in books. But I doubt very much that they will forget the people they have met here. Guatemala has gone from being an abstraction to a concrete reality. When they meet kind people of good character who have walked across Mexico and made it into the USA only to be caught and deported, "illegal immigrants" now have a face, a home, a family at whose table my students have received a nourishing and welcoming meal.

Likewise, they will not likely forget the sound of howler monkeys at night or the experience of scrambling up Maya temples still covered in a thousand years of trees and soil. They won't forget the long walk in a deep green forest and the smells of tortillas and beans cooked over a wood fire.

It is expensive to bring students so far. One could object that the money could be better spent on viewing the forest online or donating it to rainforest conservation. I disagree. I'm not in the business of dispensing information; I'm in the business of transforming lives, and not much transforms like full-bodied experience. Before we leave for Guatemala my students read papers written by wildlife conservation researchers. In Guatemala they meet those researchers in person and get to hear their stories. They hear in their tone and see in their eyes what brought them to Guatemala and what keeps them here. In such times my students go from taking in data to rethinking their lives.

It is my hope - my exuberant, perhaps not wholly rational hope - that out of such lived experience of nature my students will become people who comfort orphans and widows in their distress, who receive the foreigner into their own homes, who marvel and the world's diversity and who, for the rest of their lives, work to preserve it.

∞

The Importance of Struggling to Understand

In his speech when he was awarded the Emerson-Thoreau Medal, Robert Frost made this poignant aside about his years of struggling with one of Emerson's poems:

"I don't like obscurity and obfuscation, but I do like dark sayings I must leave the clearing of to time. And I don't want to be robbed of the pleasure of fathoming depths for myself."

"I don't like obscurity and obfuscation, but I do like dark sayings I must leave the clearing of to time. And I don't want to be robbed of the pleasure of fathoming depths for myself."

Robert Frost, "On Emerson." In Selected Prose of Robert Frost. Hyde Cox and Edward Connery Lathem, eds.(New York: Collier, 1968) p.114. (Originally delivered as an address to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences on the occasion of Frost's being awarded the Emerson-Thoreau Medal. Later published in Daedalus, Fall 1959.)I like Frost's use of "clearing" which still echoes the older meaning of "clear," that is "brighten." Frost's point is also excellent: simply explaining poetry, or great texts, to students is not enough. It is often helpful to guide them and to show them hermeneutical tools, or to speak with them about how we ourselves have grappled with texts, but we should be careful about the temptation to explain, since explanations can rob students of the pleasure of discovery. Poetry has immense value for us, and one -- just one -- of its benefits is the way that it can become the means by which we learn to solve problems that we have never encountered before.

∞

As September approaches, people keep asking me, "Are you ready to get back in the classroom?"

As early as middle school I knew I wanted to become a college professor, and I love my job. It is a delight to spend time with young people who are curious, after all.

Years ago, my friend Matt Dickerson pointed out to me that it's also my job to help those who are not curious to see why they should be. As it turns out, that work is usually delightful, too, a rewarding challenge.

So on the whole, I love my work.

But I admit I don't love classrooms, for several reasons:

First, no matter what decade, every classroom I've been in has exhibited an unhealthy tendency towards becoming cluttered with the latest technology, and most of that tech seems to take up a lot of space and to become the center of attention. I'm not opposed to technology in the classroom, not at all. But I'm opposed to letting it get in the way, as it does when the "Smart Cart" leaves me no room for my lecture notes, or when I can't seem to turn the ceiling-mounted projector on or off. I'm a fan of chalk, because chalk allows spontaneity, and it allows for much more than alphanumeric writing in neat rows. Sadly, concerns about chalk dust getting into computers is threatening to make chalkboards disappear from my classrooms. Alas. Chalk is an excellent technology, and if it vanishes, I will mourn its loss.

Second, classroom architecture is not some value-free, neutral design. Classroom architecture makes a big difference in how people teach, and how they learn:

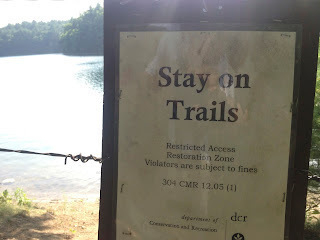

Which is why, as often as I can, I get my students out of the classroom. When we are reading Thoreau's Walking, we go for a walk. When I teach environmental philosophy, we often meet under the great tree in our campus quad, where I encourage students to daydream and to play with the grass, to look for worm-castings and owl pellets, feathers and seed-pods, invertebrates and fallen bits of bark. What good is it to gain the world of theoretical knowledge at the expense of knowledge gained through vital, haptic, bodily experience?

And this is why I am a preacher of the importance of study abroad. Not just travel, but serious, engaged, rigorous study in the classroom of life in another place. This is why I teach Classics in Greece every year, and why year after year I take students to Central America to study environmental philosophy and ecology.

More and more I've been trying to shift the learning focus in my classes from the classroom to the laboratory - where by "laboratory" I mean anywhere that allows students to learn with their whole person. I make my ancient philosophy students devote hours each semester to star-gazing, in part because this is what the ancients did, and in part because I don't want them to miss the stars. I want them to gaze in wonder at the firmament so that when they read Aristotle and Galileo they know that they've looked at what those great minds saw as well. We even occasionally take field trips to really dark places like the South Dakota Badlands so we can see the skies even better.

My environmental philosophy students must observe a square meter of earth for a semester, spending an hour at a time without a camera, drawing and writing about what they see, because it does not make sense to me to talk about the earth when you have not taken the time to sit upon it, to listen to it, to smell and taste it, and to see what other lives creep, and walk, and fly across it.

My friend Aage Jensen advocates the Norwegian philosophy of Friluftsliv, life and education outdoors. And when he organizes a conference on it, he eschews conference centers and holds the conference while walking through the mountains, or paddling a river. Because he believes that one should practice what one preaches, and that nature is always ready to teach.

To paraphrase the Stoic Musonius, teachers would do well to talk less and to take their students with them into the fields, because there they will learn far better and far more than in the lecture hall.

Teaching Outdoors

|

As early as middle school I knew I wanted to become a college professor, and I love my job. It is a delight to spend time with young people who are curious, after all.

Years ago, my friend Matt Dickerson pointed out to me that it's also my job to help those who are not curious to see why they should be. As it turns out, that work is usually delightful, too, a rewarding challenge.

So on the whole, I love my work.

But I admit I don't love classrooms, for several reasons:

First, no matter what decade, every classroom I've been in has exhibited an unhealthy tendency towards becoming cluttered with the latest technology, and most of that tech seems to take up a lot of space and to become the center of attention. I'm not opposed to technology in the classroom, not at all. But I'm opposed to letting it get in the way, as it does when the "Smart Cart" leaves me no room for my lecture notes, or when I can't seem to turn the ceiling-mounted projector on or off. I'm a fan of chalk, because chalk allows spontaneity, and it allows for much more than alphanumeric writing in neat rows. Sadly, concerns about chalk dust getting into computers is threatening to make chalkboards disappear from my classrooms. Alas. Chalk is an excellent technology, and if it vanishes, I will mourn its loss.

Second, classroom architecture is not some value-free, neutral design. Classroom architecture makes a big difference in how people teach, and how they learn:

|

| Step off the trails! Explore! An ironic sign at Walden Pond. |

And this is why I am a preacher of the importance of study abroad. Not just travel, but serious, engaged, rigorous study in the classroom of life in another place. This is why I teach Classics in Greece every year, and why year after year I take students to Central America to study environmental philosophy and ecology.

More and more I've been trying to shift the learning focus in my classes from the classroom to the laboratory - where by "laboratory" I mean anywhere that allows students to learn with their whole person. I make my ancient philosophy students devote hours each semester to star-gazing, in part because this is what the ancients did, and in part because I don't want them to miss the stars. I want them to gaze in wonder at the firmament so that when they read Aristotle and Galileo they know that they've looked at what those great minds saw as well. We even occasionally take field trips to really dark places like the South Dakota Badlands so we can see the skies even better.

My environmental philosophy students must observe a square meter of earth for a semester, spending an hour at a time without a camera, drawing and writing about what they see, because it does not make sense to me to talk about the earth when you have not taken the time to sit upon it, to listen to it, to smell and taste it, and to see what other lives creep, and walk, and fly across it.

My friend Aage Jensen advocates the Norwegian philosophy of Friluftsliv, life and education outdoors. And when he organizes a conference on it, he eschews conference centers and holds the conference while walking through the mountains, or paddling a river. Because he believes that one should practice what one preaches, and that nature is always ready to teach.

To paraphrase the Stoic Musonius, teachers would do well to talk less and to take their students with them into the fields, because there they will learn far better and far more than in the lecture hall.

|

| Nature is full of things worth seeing. |

∞

Bless You!

What should you say when someone sneezes? I've been pondering this for years. Here are my reflections on that, by way of thinking about foreign-language pedagogy, and about what it means to bless someone:

The Emperor Charles V reportedly said that as many languages as a man knows, that many times over is he a man. I don't know if that's true, but in high school I took courage from it. I was athletic, but lean, with a great build for biking and running, but too slender to be considered dangerously manly. My only formal sports were swimming and ultimate frisbee. I loved skiing and hiking and rock-climbing, but the more I exercised, the leaner I got. There was no chance I'd ever become a star athlete, and I think that realization saved me from trying to become what I was not. Although I didn't know Emerson's writing back then, I nevertheless arrived at an Emersonian conclusion: there are as many kinds of manliness, and courage, as there are men and women to embody them. Emerson puts it like this:

This turns out to be a good way to learn one's own language, too. Not everything can be translated, and when you find something in your native tongue that's hard to say in another language, you've found something that is a unique possession of the speakers of your language. Or when you learn that one word in your language takes many forms in another language, you begin to see how your cultural heritage has come equipped with some blind spots. The same is true of grammar, of inflection, of syntax, and so on.

So learning another language is not simply a matter of replacing one vocabulary with another. Learning a language means learning a culture, a history, a literature.

(This is why language-learning software can help, but it's not enough, and it's no substitute for excellent teachers and for studying abroad.)

In middle school, as I was trying to actualize all my potential and to become as many men as I could be, I spent a lot of time learning basic phrases and grammar in other languages. How do you greet someone in this language? How do you say goodbye? How do you ask for what you want? These tend to be fairly straightforward in the languages I studied.

But some phrases were harder. How do you say "Please"? That word is, after all, a contraction of a whole clause, "If it please you," with a subjunctive verb. It's not like a name for an object or a place, which might be easily translated; it's a way of calling on a whole tradition of regarding the wishes of others as important - or at least, of pretending to honor those wishes. Now, most of the languages I studied had simple ways of saying "please," but along the way I discovered that not all English speakers consider "please" to be correct. Some religious communities, for instance, regard such words as unnecessary; we should be willing to give what we're asked for without demanding that the other regard our wishes as important, they reason.

Another phrase similarly exposed something about cultures: what do you say when someone sneezes? In many languages, the answer is that you say "Your health!" Many English speakers I know use the German Gesundheit without knowing that this is what they are saying, in another language. That's fascinating: we feel the need to say something, even if we don't know what the word means.

When I first met my frosh college roommate, Nick, he sneezed. I said the customary thing: "Bless you!" He looked at me oddly, and didn't say anything. Over the coming weeks, I repeated the phrase each time he sneezed. Finally, he asked me "Why do you keep saying that?" I realized I hadn't any better answer than to say that's what I heard others do. His question got me wondering why we acknowledge sneezes.

After all, we don't say something to accompany other bodily functions, do we? Is there a stock phrase for hiccups, or burps? For a rumbling belly? A cough? A yawn?

Over the years, it started to bother me that others felt the need to comment on my sneezes. When I ask people why they do it, I usually get some lame reply about how it's because long ago people believed that sneezes were a sign of some dangerous spiritual or physical ailment; or that it had to do with fear of the Black Plague; or that it was a response to the fear that sneezes were signs of demonic possession; and in any case, sneezes needed to be countered with blessings.

Okay, fine. I'll let the Middle Ages off the hook next time they bless my sneezing. But why do YOU do it? The answer seems to be cultural habit. It's not a necessity of nature, but something we've made ourselves do until we've forgotten why we do it. It's a thoughtless reflex, and I think this is what annoys me.

Now, after years of being a curmudgeon and a grouch about this, I'm starting to reconsider my objection to these responses to my sternutations. On the one hand, these blessings are thoughtless, and they demand a reply of "thank you" when frankly, I'm still recovering from a sneeze and would rather not say anything. On the other hand, perhaps we shouldn't want fewer blessings in our lives, but more of them, or at least more sincere ones.

As I think back over my life, I've received these blessings often from strangers on a bus or a subway, or in a park in a foreign city. People who do not know me stop their activity to speak a word of blessing into my life, to look me in the eye and put into simple words their wishes for my good health.

Speaking does not make things so, not instantly, anyway. But putting things into words is nevertheless very powerful. I'm not talking magic here; I'm talking about the way our words affect ourselves and others. Naming is powerful. When our inarticulate anger or frustration evolves into naming someone as the one who needs to be punished, the person becomes a criminal, something less than a person. The greater the crime, the lesser the human. Because naming is powerful, cursing is powerful. Which is why I taught my kids that it's not words that are bad, but the uses of words.

And if history teaches us anything at all, it shows us how easy we find it to curse others, to come up with simple, curt, dehumanizing names for entire classes of others. We find it easy not to look others in the eye but to look no further than the skin, or to look through others as though they were not there. We find it easy to curse those who live across borders of towns and nations, those who drive in front of us or behind us, those whose faces we never see and whom we know only through a few words we've read online.

In light of that, I suppose that if you want to bless me--indeed, if you find it hard not to bless me--that should be a welcome thing. Just give me a minute to recover from my sneeze before I thank you. And may you be blessed, too.

The Emperor Charles V reportedly said that as many languages as a man knows, that many times over is he a man. I don't know if that's true, but in high school I took courage from it. I was athletic, but lean, with a great build for biking and running, but too slender to be considered dangerously manly. My only formal sports were swimming and ultimate frisbee. I loved skiing and hiking and rock-climbing, but the more I exercised, the leaner I got. There was no chance I'd ever become a star athlete, and I think that realization saved me from trying to become what I was not. Although I didn't know Emerson's writing back then, I nevertheless arrived at an Emersonian conclusion: there are as many kinds of manliness, and courage, as there are men and women to embody them. Emerson puts it like this:

“It is he only who has labor, and the spirit to labor, because courage sees: he is brave, because he sees the omnipotence of that which inspires him. The speculative man, the scholar, is the right hero. Is there only one courage, and one warfare? I cannot manage sword and rifle; can I not therefore be brave? I thought there were as many courages as men. Is an armed man the only hero? Is a man only the breech of a gun, or the hasp of a bowie-knife? Men of thought fail in fighting down malignity, because they wear other armour than their own.”So I threw myself into doing what I was made to do with joy, and to living a brave life in my own way. Some people find learning a foreign language terrifying; I do not. I'm one of those people blessed with an unusual ability to learn foreign languages quickly and with little effort. When I'm around a new language, I listen to its music and its rhythms and make them my own, and I begin to take apart the language as I hear it, so I can think with it, and watch its parts move. And I ask a lot of questions: How do you say this in your language? What does this mean? When do you say that?– R.W. Emerson, Commencement Address given at Middlebury College on July 22, 1845, in Emerson At Middlebury College, Robert Buckeye, ed. (Middlebury, Vermont: Friends of the Middlebury College Library, 1999), p. 39.

This turns out to be a good way to learn one's own language, too. Not everything can be translated, and when you find something in your native tongue that's hard to say in another language, you've found something that is a unique possession of the speakers of your language. Or when you learn that one word in your language takes many forms in another language, you begin to see how your cultural heritage has come equipped with some blind spots. The same is true of grammar, of inflection, of syntax, and so on.

So learning another language is not simply a matter of replacing one vocabulary with another. Learning a language means learning a culture, a history, a literature.

(This is why language-learning software can help, but it's not enough, and it's no substitute for excellent teachers and for studying abroad.)

In middle school, as I was trying to actualize all my potential and to become as many men as I could be, I spent a lot of time learning basic phrases and grammar in other languages. How do you greet someone in this language? How do you say goodbye? How do you ask for what you want? These tend to be fairly straightforward in the languages I studied.

But some phrases were harder. How do you say "Please"? That word is, after all, a contraction of a whole clause, "If it please you," with a subjunctive verb. It's not like a name for an object or a place, which might be easily translated; it's a way of calling on a whole tradition of regarding the wishes of others as important - or at least, of pretending to honor those wishes. Now, most of the languages I studied had simple ways of saying "please," but along the way I discovered that not all English speakers consider "please" to be correct. Some religious communities, for instance, regard such words as unnecessary; we should be willing to give what we're asked for without demanding that the other regard our wishes as important, they reason.

|

| Modern saints at Westminster Abbey; Their stories are a blessing. |

When I first met my frosh college roommate, Nick, he sneezed. I said the customary thing: "Bless you!" He looked at me oddly, and didn't say anything. Over the coming weeks, I repeated the phrase each time he sneezed. Finally, he asked me "Why do you keep saying that?" I realized I hadn't any better answer than to say that's what I heard others do. His question got me wondering why we acknowledge sneezes.

After all, we don't say something to accompany other bodily functions, do we? Is there a stock phrase for hiccups, or burps? For a rumbling belly? A cough? A yawn?

Over the years, it started to bother me that others felt the need to comment on my sneezes. When I ask people why they do it, I usually get some lame reply about how it's because long ago people believed that sneezes were a sign of some dangerous spiritual or physical ailment; or that it had to do with fear of the Black Plague; or that it was a response to the fear that sneezes were signs of demonic possession; and in any case, sneezes needed to be countered with blessings.

Okay, fine. I'll let the Middle Ages off the hook next time they bless my sneezing. But why do YOU do it? The answer seems to be cultural habit. It's not a necessity of nature, but something we've made ourselves do until we've forgotten why we do it. It's a thoughtless reflex, and I think this is what annoys me.

Now, after years of being a curmudgeon and a grouch about this, I'm starting to reconsider my objection to these responses to my sternutations. On the one hand, these blessings are thoughtless, and they demand a reply of "thank you" when frankly, I'm still recovering from a sneeze and would rather not say anything. On the other hand, perhaps we shouldn't want fewer blessings in our lives, but more of them, or at least more sincere ones.

As I think back over my life, I've received these blessings often from strangers on a bus or a subway, or in a park in a foreign city. People who do not know me stop their activity to speak a word of blessing into my life, to look me in the eye and put into simple words their wishes for my good health.

Speaking does not make things so, not instantly, anyway. But putting things into words is nevertheless very powerful. I'm not talking magic here; I'm talking about the way our words affect ourselves and others. Naming is powerful. When our inarticulate anger or frustration evolves into naming someone as the one who needs to be punished, the person becomes a criminal, something less than a person. The greater the crime, the lesser the human. Because naming is powerful, cursing is powerful. Which is why I taught my kids that it's not words that are bad, but the uses of words.

And if history teaches us anything at all, it shows us how easy we find it to curse others, to come up with simple, curt, dehumanizing names for entire classes of others. We find it easy not to look others in the eye but to look no further than the skin, or to look through others as though they were not there. We find it easy to curse those who live across borders of towns and nations, those who drive in front of us or behind us, those whose faces we never see and whom we know only through a few words we've read online.

In light of that, I suppose that if you want to bless me--indeed, if you find it hard not to bless me--that should be a welcome thing. Just give me a minute to recover from my sneeze before I thank you. And may you be blessed, too.

∞

Great Books, Pedagogy, and Hope

Great Books and the Great Conversation

About fifteen years ago I enrolled in the "Great Books" M.A. program at St John's College in Santa Fe, New Mexico. It was one of the best decisions I've ever made.

Much as I appreciate my undergraduate education, too often it rewarded me for concealing my ignorance and emphasizing what I already knew. The problem, of course, is that my ignorance was thus shielded from the sterilizing sunlight of others' scrutiny and instruction.

Confessing Our Ignorance

Matthew Davis, my tutor and advisor at St John's, won me over to another way of viewing literature when, on one of the first days we met, he pointed to a passage in Plato's Republic and said "I have always wondered what Plato means by that." Looking up at the class, he asked, "Do any of you have any ideas about what he might be trying to say?"

Mr. Davis is the first professor I recall who openly confessed his ignorance, and who thereby modeled what it means to open oneself to the instruction of a great text. Not much has shaped my academic life as much as that.

Grappling With Classic Texts

As I have begun to mature into my own place as a teacher, I often think that this is the best thing I can give my students: not professorial and authoritative descriptions of texts, but an example of what it means to be a student. I can try to be an example of someone who sits with texts and listens to them, grappling with them, like Jacob with the angel or like Menelaus with Proteus: persistently grappling with my superior and refusing to let go until I receive a blessing. (Selah.)

For the last few years I have been seeking out and reading classic novels. As I read them I feel like an apprentice architect touring buildings, looking not just at the outward form and function but looking for the supporting structure, trying to notice the decisions the artist made about what to include and what to omit.

Along the way, I have begun trying to write bits of dialogue, scenes, characters, and other elements of fiction. I'm not trying to write a novel so much as trying to perform experiments the way high school science students do in labs: not to discover something new but to learn haptically, kinesthetically, experientially what the masters already know. I can't say that I've learned to write novels, so don't expect anything from me there. But as I've paid attention, I feel I've begun to squeeze some blessings out of the books, including some unexpected ones.

I've noticed, for instance, that Craig Nova writes about the olfactory sense in a way that makes me notice aromas I never noticed before. John Steinbeck has begun to make me care more about friendship, and about the people in front of me. Harold Frederic has me rethinking my early faith, and this is helping me look ahead as I try to nurture it into a faith worth having. Novels are helping me see the world differently.

So What Does This Have To Do With Hope?

I just finished Graham Greene's The Honorary Consul. Apparently this was Greene's favorite of his own works, and I can see why. Like many of the really good novels I've read, it has left me thinking about a range of topics, and longing for someone to talk about it with.

Which brings me to hope. I started reading Greene because Bill Swart, my friend and colleague, told me about how good Greene's novels are. Bill was right about this, so I sought him out the other day to talk more about Greene. We said too much to cover it all here, but Bill said something I can't bear not to repeat. When we began discussing Greene's The Power and the Glory, Bill said "That book gave me hope that my own self-perception might be wrong."

If you know the novel, you know why, because you know how Greene's characters wrestle with being both sinners and saints. If you don't know the novel, let me recommend it to you.

We Should Keep Teaching And Reading Fiction

I still have a lot to learn about novels. I doubt I'll ever write one - or a good one, anyway. But I'm delighting in reading them. Perhaps that's why they matter so much: they delight us, and capture us. When I'm in a good book I feel like I'm really in it. I stop seeing words on a page and start seeing, with some inner eye, the world the novelist sees.

And like all my other travels, journeys into fiction leave me a different person. I see different possibilities, I see -- and smell -- my world differently. I know it's important to teach young people to read non-fiction, but teaching fiction might be for them what The Power and the Glory was for Bill: a tonic for his soul, a sweet drink of hope that didn't just entertain, but that allowed him to envision his life, his work, and his purpose in an entirely new way.

About fifteen years ago I enrolled in the "Great Books" M.A. program at St John's College in Santa Fe, New Mexico. It was one of the best decisions I've ever made.

Much as I appreciate my undergraduate education, too often it rewarded me for concealing my ignorance and emphasizing what I already knew. The problem, of course, is that my ignorance was thus shielded from the sterilizing sunlight of others' scrutiny and instruction.

Confessing Our Ignorance

Matthew Davis, my tutor and advisor at St John's, won me over to another way of viewing literature when, on one of the first days we met, he pointed to a passage in Plato's Republic and said "I have always wondered what Plato means by that." Looking up at the class, he asked, "Do any of you have any ideas about what he might be trying to say?"

Mr. Davis is the first professor I recall who openly confessed his ignorance, and who thereby modeled what it means to open oneself to the instruction of a great text. Not much has shaped my academic life as much as that.

Grappling With Classic Texts

As I have begun to mature into my own place as a teacher, I often think that this is the best thing I can give my students: not professorial and authoritative descriptions of texts, but an example of what it means to be a student. I can try to be an example of someone who sits with texts and listens to them, grappling with them, like Jacob with the angel or like Menelaus with Proteus: persistently grappling with my superior and refusing to let go until I receive a blessing. (Selah.)

For the last few years I have been seeking out and reading classic novels. As I read them I feel like an apprentice architect touring buildings, looking not just at the outward form and function but looking for the supporting structure, trying to notice the decisions the artist made about what to include and what to omit.

Along the way, I have begun trying to write bits of dialogue, scenes, characters, and other elements of fiction. I'm not trying to write a novel so much as trying to perform experiments the way high school science students do in labs: not to discover something new but to learn haptically, kinesthetically, experientially what the masters already know. I can't say that I've learned to write novels, so don't expect anything from me there. But as I've paid attention, I feel I've begun to squeeze some blessings out of the books, including some unexpected ones.

I've noticed, for instance, that Craig Nova writes about the olfactory sense in a way that makes me notice aromas I never noticed before. John Steinbeck has begun to make me care more about friendship, and about the people in front of me. Harold Frederic has me rethinking my early faith, and this is helping me look ahead as I try to nurture it into a faith worth having. Novels are helping me see the world differently.

So What Does This Have To Do With Hope?

I just finished Graham Greene's The Honorary Consul. Apparently this was Greene's favorite of his own works, and I can see why. Like many of the really good novels I've read, it has left me thinking about a range of topics, and longing for someone to talk about it with.

Which brings me to hope. I started reading Greene because Bill Swart, my friend and colleague, told me about how good Greene's novels are. Bill was right about this, so I sought him out the other day to talk more about Greene. We said too much to cover it all here, but Bill said something I can't bear not to repeat. When we began discussing Greene's The Power and the Glory, Bill said "That book gave me hope that my own self-perception might be wrong."

If you know the novel, you know why, because you know how Greene's characters wrestle with being both sinners and saints. If you don't know the novel, let me recommend it to you.

We Should Keep Teaching And Reading Fiction

I still have a lot to learn about novels. I doubt I'll ever write one - or a good one, anyway. But I'm delighting in reading them. Perhaps that's why they matter so much: they delight us, and capture us. When I'm in a good book I feel like I'm really in it. I stop seeing words on a page and start seeing, with some inner eye, the world the novelist sees.

And like all my other travels, journeys into fiction leave me a different person. I see different possibilities, I see -- and smell -- my world differently. I know it's important to teach young people to read non-fiction, but teaching fiction might be for them what The Power and the Glory was for Bill: a tonic for his soul, a sweet drink of hope that didn't just entertain, but that allowed him to envision his life, his work, and his purpose in an entirely new way.

∞

This year I am playing around with Google Wave's map feature and wondering if I can use Wave to help prepare my students to make the most of our limited time in Greece.

Do you have suggestions for how I can use this for my course? Are you also new to Wave and interested in Greece? If so, send me a wave at dr.dlohara@googlewave.com and I'll include you in my "sandbox" where I'm playing around with the possibilities.

(Photo credit: Dr. Jeffrey A. Johnson, Providence College)

Google Wave and My Course in Greece

Each year I teach a course in Greece, and I require my students to make presentations at a variety of archaeological and cultural sites.

This year I am playing around with Google Wave's map feature and wondering if I can use Wave to help prepare my students to make the most of our limited time in Greece.

Do you have suggestions for how I can use this for my course? Are you also new to Wave and interested in Greece? If so, send me a wave at dr.dlohara@googlewave.com and I'll include you in my "sandbox" where I'm playing around with the possibilities.

(Photo credit: Dr. Jeffrey A. Johnson, Providence College)

∞

Russell Frank and the 4/40 Program

One semester when I was in grad school at Penn State I was assigned to teach a course called "Media Ethics." I had no idea how to teach such a course, so I called up Dr. Russell Frank to ask him for a textbook recommendation.

Frank wrote a weekly column for the Centre Daily Times. At the time, he was an untenured professor in the Department of Communications at Penn State. Even though he did not know me, and surely had many demands on his time, Frank offered to meet me for coffee.

We met for three hours that day, during which I took pages of notes and basically wrote my syllabus for the course. He also gave me a stack of textbooks from his office, offered to guest-lecture in my class (which he later did, several times) and then, to top it all off, he paid for the coffee.

I protested that I was getting all the benefit from this and that I should pay. He replied, "My rule is this: the student never pays." Instead of paying him back, he said, I could "pay it forward" to some of my students.

So I began what I now call The 4/40 program. Whenever I meet students for a meal or coffee, I explain this to them: during their four years of undergraduate study with me (and if they visit me while they're in grad school) I pay. If they want, then they can visit me sometime in the next forty years and take me out for a meal or, better yet, they can use the next forty years to take someone else out for a meal.

I find these meals are always worthwhile. Much of the best learning in college happens outside the classroom, in informal conversations, often while breaking bread together. I teach because I love teaching, and these meals or coffees have provided me with some of my favorite classrooms: coffee shops, restaurants, the dining room table or kitchen in our home.

So to any of my students who may be reading this: don't thank me, thank Russell Frank (you can find his email at the link above or right here if you want). And if you benefited from the coffee, or the meal, pay it forward to someone else.

And come back and visit sometime.

Frank wrote a weekly column for the Centre Daily Times. At the time, he was an untenured professor in the Department of Communications at Penn State. Even though he did not know me, and surely had many demands on his time, Frank offered to meet me for coffee.

We met for three hours that day, during which I took pages of notes and basically wrote my syllabus for the course. He also gave me a stack of textbooks from his office, offered to guest-lecture in my class (which he later did, several times) and then, to top it all off, he paid for the coffee.

I protested that I was getting all the benefit from this and that I should pay. He replied, "My rule is this: the student never pays." Instead of paying him back, he said, I could "pay it forward" to some of my students.

So I began what I now call The 4/40 program. Whenever I meet students for a meal or coffee, I explain this to them: during their four years of undergraduate study with me (and if they visit me while they're in grad school) I pay. If they want, then they can visit me sometime in the next forty years and take me out for a meal or, better yet, they can use the next forty years to take someone else out for a meal.

I find these meals are always worthwhile. Much of the best learning in college happens outside the classroom, in informal conversations, often while breaking bread together. I teach because I love teaching, and these meals or coffees have provided me with some of my favorite classrooms: coffee shops, restaurants, the dining room table or kitchen in our home.

So to any of my students who may be reading this: don't thank me, thank Russell Frank (you can find his email at the link above or right here if you want). And if you benefited from the coffee, or the meal, pay it forward to someone else.

And come back and visit sometime.