Philosophy

Reason For Hope

Apologetics and Postmodernism

When I first taught it, I made it a class about apologetics and postmodernism. By “apologetics” I mean the work of giving a reasoned account of one’s commitments; by “postmodernism,” I mean the suspicion that what look like reasoned accounts might have unexamined depths and layers to them. In the context of theism—and in particular Christian theism—apologetics has a long history that reaches back to the early years of Christianity. Saint Peter wrote in his longer letter that Christians should always be prepared to give a reasoned defense of the hope they bore within them. That phrase “reasoned defense” is a translation of the Greek word apologia, which can mean a legal defense, and from which we get our word “apologetics.”

When Saint Paul of Tarsus found himself in Athens, speaking to Stoic and Epicurean philosophers on the Areopagus, he tried to explain his beliefs not in the terms of his culture but in theirs. He doesn’t seem to have won many over to his views that day, but if nothing else was accomplished, at the end of the conversation it was clearer where Paul and the Greek philosophers were in agreement and where they disagreed. If immediate conversion was the aim of his speech, it wasn’t a great speech. But if he aimed to build a bridge of mutual understanding, I’d say he was pretty successful.

One of the keys to his success, I think, was familiarity with the culture around him. I’ve written about this elsewhere, so I won’t belabor it here, but I’ll just point out that Paul quoted two Greek philosophical poets, Epimenides and Aratos, and he did so in a culturally appropriate and significant place, since several centuries before Paul’s travels, Epimenides (who was from Crete) also traveled to Athens and also spoke on the Areopagus about the gods and salvation.

Understanding Atheism(s)

A few years after I started teaching that course, I shifted the course to take seriously the “New Atheists.” I figured that if my religious students graduated without hearing the strongest challenges to their faith, I, as a professor who teaches theology, was letting them down. I wanted them to know that soon they’d hear strong arguments against their religious heritage, beliefs, and practices, and that these arguments should be taken seriously. For my Christian students, I framed this as a way of living the commandment to love God with one’s mind.

Of course, only some of my students are religious, and some of the religious students aren’t Christians. (I’m at a Lutheran university in a small Midwestern city, so until recently most of them were at least culturally Christian; that’s changing quickly, though.) I wanted this to be a class that was helpful for everyone, so I started to turn this into a class about mutual understanding. I now teach my students how to distinguish between a dozen different kinds of (and reasons for) atheism, lest they make the mistake of oversimplifying the complexity of their neighbors and of themselves.

Understanding and Agapic Love

Arguments about religion can quickly become unkind. Many of us have been wounded in the name of religion, and those wounds heal slowly, if at all. How could we make this into a class that was—on its surface, and in its content—about theology and philosophy, while really making it about something like mutual care?

I just mentioned that great commandment: Love God with your heart, soul, mind, and strength, Jesus said, echoing Moses. Then he added a second commandment: love your neighbor as yourself. Everything else hangs on these two commandments, he said.

Explaining those two commandments would be almost as hard as trying to keep them, so I won’t try to do so here. I’ll just point out that it’s fascinating to command someone to love someone else; that the love that’s called for here is agapic love, i.e. the love that seeks the good and flourishing of the beloved; and that the commandments are so lacking in specificity as to call for both extensive commentary and continued practice. They’re vague commandments, which means they require us to work them out in community, over time. And in all likelihood we’ll never get them right. That may seem like a weakness, but it also strikes me as offering the freedom to try and to fail and to help one another to try again.

Anxiety, Ultimate Concerns, and Societal “Stress Fractures”

Which brings me to the most recent incarnation of my Theology and Philosophy in Dialogue class. Over the last few years it seems to me that my students have become more anxious about their economic futures, more stressed about exams and jobs, more focused on education and work as competition for rank. I could be wrong, but as the stress and anxiety have grown, it seems like my students are so busy jockeying for position that they have a hard time putting the cause of their stress into words. On top of all this, here in the United States, it feels like we’ve been using stronger words so that we can give voice to our anxiety more quickly. We aren’t broken, but we’ve got lots of hairline stress fractures that are too small to see. We aren’t bleeding, but we’ve got a constant dull ache.

In other words, it seems like we’re fearful without being able to identify the object of our fear, and that has us prepared to see enemies wherever we look. This does not make it easy to love our neighbors as ourselves (unless we also have that kind of distrust of ourselves, which is a real possibility, I suppose.) And at least in the way Paul Tillich described God: whatever we regard as our ultimate concern functions as our God. When economic anxiety, jostling for rank, or fear of losing one’s place in the future, (these are all ways of saying the same thing, I think) take on the role of “ultimate concern” in our lives, they become our gods.

The course I’m teaching this semester still has traces of every previous semester’s influences. We talk a little about apologetics, and that’s a helpful way of teaching students about logic, inference, probability, and certainty. (Ask some of them about “doxastic certainty” or my “haystack problem” and you’ll see what I mean.)

And we still talk about postmodernism, though as my career has shifted from the philosophy of religion to environmental philosophy, ethics, and policy, I’m inclined to follow Scott Russell Sanders’ view (see note, below) that if we spend too much time theorizing and not enough time caring for the world we share, incredulity towards metanarratives can quickly become a new metanarrative that we fail to examine sufficiently.

And we still talk about atheisms. This semester I have sketched a dozen forms of atheism once again, and we’re now working our way through them.

Friendship, and “Best Construction”

But the aim of the class, more than anything, is friendship.

I told all the students that this was the case on the first day of class.

And here, I think, is where Theology and Philosophy can have a really helpful dialogue in our time. I teach at a Lutheran university, so it’s fitting to invoke Luther. In his Small Catechism, he offers some commentary on the Ten Commandments. His commentary on the eighth commandment is helpful. The commandment reads simply, like this:

“Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor.”Like the other commandments I’ve mentioned, it is only a few words long. And like those others, it leaves room for commentary. Luther’s commentary does something that I find very helpful. While the commandment is negative (“thou shalt not,” it says) Luther thought that alongside each negative commandment was something positive. So he writes:

What does this mean?--Answer. We should fear and love God that we may not deceitfully belie, betray, slander, or defame our neighbor, but defend him, [think and] speak well of him, and put the best construction on everything.”This is akin to what Plato offers in several ways in his Republic, and to Ulpian’s legal principle of “giving to each person their due,” (see note, below) but it goes a little further, with an agapic tinge: Luther doesn’t just tell us not to lie, nor does he tell us to be simply honest, but to put the best construction on everything.

This is hard.

“A Mutual, Joint-Stock World, In All Meridians”

It’s especially hard when we feel that others are getting ahead of us, and that we are in a competition with everyone else. If the world is a zero-sum game, then everyone run, and the Devil take the hindmost. But what if Queequeg is right? When Queequeg sees a fellow sailor drowning and no one moves to save the sailor, Queequeg leaps into the water to save his fellow. There is no question of whether they are of the same tribe, the same party, the same race, the same team. Queequeg is, as far as anyone aboard the ship knows, a cannibal. And yet the narrator, observing Queequeg’s agapic care for his fellow sailor, offers this comment:

Was there ever such unconsciousness? He did not seem to think that he at all deserved a medal from the Humane and Magnanimous Societies. He only asked for water—fresh water—something to wipe the brine off; that done, he put on dry clothes, lighted his pipe, and leaning against the bulwarks, and mildly eyeing those around him, seemed to be saying to himself—“It’s a mutual, joint-stock world, in all meridians. We cannibals must help these Christians.” -- Herman Melville, Moby Dick. (New York: Signet, 1980) 76

It’s much easier to approach theological conversations with the idea that our theology is a weapon and that our enemies are those with whom we disagree. It’s so easy to forget what Saint Paul wrote, that we don’t fight against flesh and blood, but against far less tangible, invisible forces that would have us view our neighbors with malice.

Could we approach theology the way Queequeg approaches the plight of his fellow sailor? Is it possible to maintain one’s cherished beliefs while recognizing that one’s object of “ultimate concern” might be something we don’t yet see with certainty and clarity? I cannot speak for others, so I’ll just offer this confession: I’m aware of a capacity in myself to care more for my theology than for the God that my theology claims to describe. In simpler terms: my own theology can become so dear to me that it becomes an idol, displacing the very God I set out to love and serve. And how to I love and serve my God? So far, the best I can offer you is this: I should love God with all I am, and I should love my neighbor as myself. Does that seem unclear to you? It does to me. Which means I need all the help I can get in clarifying my vision. Right now I see in a glass, darkly.

The philosopher Jonathan Lear suggests a principle akin to Queequeg’s, and to Luther’s: the principle of humanity. He describes it like this:

“The interpretation thus fits what philosophers call the principle of humanity: that we should try to interpret others as saying something true—guided by our own sense of what is true and of what they could reasonably believe.” -- Jonathan Lear, Radical Hope. 4 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006) (See note below)The Episcopal Church’s Book of Common Prayer offers another commentary on the fourth commandment, the commandment not to take the name of God in vain. The Book of Common Prayer rephrases the commandment like this:

You shall not invoke with malice the Name of the Lord your God.

Amen. Lord have mercy.The rephrasing is a commentary on “in vain.” Invoking God’s name in vain is equated with invoking it with malice, that is, with the opposite of agapic love.

Conclusion

It’s appropriate to me that I teach this course in Lent each year. Lent is a good time for self-examination, and that includes an examination of all kinds of pieties and supposed certainties. What is it that we hold to be of ultimate concern? What do we love with all our heart, soul, mind, and strength? That might just be playing the role of a god in our lives. If so, does that God help us to love our neighbors as ourselves?

I could be wrong in all I say in this class. I enter it with “fear and trembling,” knowing that there’s so much I don’t know, and knowing that many of my students might be wiser than I am. I know they might have seen the divine far more clearly than I ever will in this life.

But oh, how I want them to live well, not to be entangled by anxious grief, not to be afraid of the future, not to be burdened by relentless suspicions and fears.

Yes, there are other subjects I could teach, and yes, there are other jobs I could do. But for me, right now, this one feels like a good way to reexamine my own ultimate concerns, and a good way to help others to do the same. May I do so without malice, with agapic love, and with the constant practice of putting the best construction on everything.

Amen. Lord, have mercy.

*****

Notes:

* Scott Russell Sanders: I'm thinking of his essay, "The Warehouse and the Wilderness," and in particular the opening pages of that essay. You can find it in A Conservationist Manifesto, beginning on page 71. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009)

* Ulpian's words are cited in Justinian, Institutes, Book 1, Title 1, Sec. 3.

* Lear has an endnote at the end of this sentence. It reads: “This principle is also known as the ‘principle of charity,’ and the most famous arguments for it are given by Donald Davidson. See his “Radical Interpretation,” in Inquiries Into Truth And Interpretation (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984), pp. 136-137; “Belief and the Basis of Meaning,” ibid., pp. 152-153; “Thought and Talk,” ibid., pp. 168-169; “On the Very Idea of a Conceptual Scheme,” ibid., pp. 196-197; “The Method of Truth in Metaphysics,” ibid., pp. 200-201.”

SPUnK: The Society for the Preservation of Unnecessary Knowledge

James is a Philosophy and Classics major at Augustana University, and he's also the Prime Minister of SPUnK, a campus group I advise at Augustana University.

SPUnK - the Society for the Preservation of Unnecessary Knowledge - is devoted to learning about things we don't need to learn about, because we think unnecessary knowledge is worth preserving and promoting. We distinguish between those things students are told they must study in order to get a job, and those things that we study because there is delight in wonder, and in learning new things, even if we don't yet see their practical use. As both Plato's Socrates and Aristotle pointed out, the love of wisdom begins in wonder, and we seek knowledge not for some simple or material gain but for the satisfaction of wonder and out of a desire to know. Here's Aristotle:

"Now he who wonders and is perplexed feels that he is ignorant (thus the myth-lover is in a sense a philosopher, since myths are composed of wonders); therefore if it was to escape ignorance that men studied philosophy, it is obvious that they pursued science for the sake of knowledge, and not for any practical utility.The actual course of events bears witness to this; for speculation of this kind began with a view to recreation and pastime, at a time when practically all the necessities of life were already supplied. Clearly then it is for no extrinsic advantage that we seek this knowledge; for just as we call a man independent who exists for himself and not for another, so we call this the only independent science, since it alone exists for itself."*Or, as Charles Peirce once put it, science is the practice of those who desire to find things out.**

This is what SPUnK is all about.

James and Hugh will teach you about paper towns, curiosity, education, Abraham Flexner, Albert Einstein, Rubik's Cubes, and other unnecessary knowledge. It's a short interview, well worth a few minutes of your time. Unnecessary knowledge is worth quite a lot more than a little of our time, after all.

* For two places Plato and Aristotle say this, see Plato's Theaetetus 155b and Aristotle's Metaphysics 982b.)

** Peirce writes about this in the first chapter of Justus Buchler's The Philosophical Writings of Peirce.

Good Education Should Lead To Good Questions

[....]

"If the aim of education is to gain money and power, where can we turn for help in knowing what to do with that money and power? Only a disordered mind thinks that these are ends in themselves. Socrates offers us the cautionary tale of the athlete-physician Herodicus, who wins fame and money through his athletic prowess and medicine, then proceeds to spend all his wealth trying to preserve his youth. This is what we mean by a disordered mind. He has been trained in the STEM fields of his time, and his training gains him great wealth, but it leaves him foolish enough to spend it all on something he can never buy."

From my latest article, co-authored with John Kaag, in The Chronicle of Higher Education. Read it all here.

Why Does A Philosophy Professor Write About Trout?

To this question I have three brief replies, which I'll say more about later.

The first is that this book really is about those things, even if it won't appear to be so at first blush.

The second is that in fact, I think more philosophers should turn our attention to the matter of lived experience, to our technology, to our tools, and to our ways of knowing the world. It's not enough to know things about the world; we ought to ask just how we know the things we know, and how our tools and our very modes of life and habits affect that knowledge. And everything that hangs on that knowledge.

And for my third brief reply, I turn to Edward Mooney, who, in his introduction to Henry Bugbee's beautiful book, The Inward Morning, recalls a question Martin Heidegger asked Bugbee in August of 1955: “What occasion prompts philosophical reflection?”

Mooney writes that no doubt Heidegger “anticipated a flat American response. Yet he found his question returned in a Socratic reversal. Bugbee simply asked, echoing a Basho haiku, 'Could the sound of a fish leaping at a fly at dawn suffice?'”

"Hit The Road, Philosophy"

"If philosophy is, as the name suggests, about loving wisdom, then it shouldn’t be something that is practised by only an erudite few. The argument that wisdom is valuable for everyone, and the life spent pursuing it is itself a good life is not some sort of Pollyanna idealism, but a pragmatic hope that philosophical reflection (what academic and novelist David Foster Wallace simply called “choosing what to think about”) can and does give life meaning."You can read it all here.

What Are Philosophy's Flaws?

She wanted to know, she said, because she was thinking seriously about studying more philosophy, and for her, thinking seriously about something means considering something from all angles. She knows that ideas give birth to other ideas, and to practical consequences.

I don't think I gave her a very good answer at the time, but I've continued to think about it because it strikes me as a good question asked for a good reason.

Not long ago I was re-reading the Stoic philosopher Gaius Musonius Rufus. Of the four major Roman Stoics, he's probably the least well-known. Epictetus, Seneca and Marcus Aurelius all left substantial writings, but Musonius did not.

Rather, Musonius is known chiefly through the notes his students left behind. In fact, this is one of the reasons I like him so well: whatever became of his writings, his life made a difference for his students. His teaching mattered so much that they refused to let his life vanish from history.

There's another reason I like Musonius: he insisted that philosophy is for women, not just for men. Since the student whom I invited to study philosophy is also a woman, I want to try to give a better answer to her question by turning to Musonius now.

Once, when Musonius made the bold invitation for women to join the Stoic philosophers, someone asked him: won't studying philosophy make the women obstinate, independent, and opinionated?

He replied that in fact, it might do just that. Musonius recognized that the question was a question about the same thing my student was asking about: philosophy's flaws. Philosophy often makes us better thinkers, but it can also make us obnoxious to our neighbors when we care more about the ideas than about the people whose lives are connected to the ideas.

Musonius then quickly pointed out that the question is irrelevant, however, because what is true of women is also true of men in this regard. Like Augustine several centuries later, Musonius argued that women and men have equal intellectual powers. If philosophy entails the development and strengthening of our native intellect, then surely women will benefit from it just as much as men.

It would appear that the questioner wasn't concerned about people becoming opinionated, independent thinkers, but about women becoming opinionated, independent thinkers. What began as a question about the vices of philosophy quickly exposes itself as a question that reveals the bias of the questioner -- a bias that philosophy would be more than happy to correct.

This brings me to my student's question: Yes, philosophy has flaws, and one of its chief flaws is that when it is combined with a lack of kindness, it can amplify that unkindness.

But it also has the power to expose that unkindness in a pretty keen way. And when it is combined with kindness and positive regard for our neighbors -- with what we sometimes call agapé, or love -- it can be something that causes kindness to grow.

I don't mean that philosophy is a panacaea, or that it will do all good things for us, all on its unattended own.

But I do mean that you, my student, have very real native intelligence, and it pleases me to see it in you. And I would love to see it grow. To point to Augustine once more: Augustine found philosophy to be helpful for his own self-understanding, for his seeking after God, and for keeping his church from descending into irrationality. He regarded it as a way to "love God with his mind."

I wouldn't ask you, my student, to give up your nursing major. Quite the opposite! Just as surely as women need philosophy, I think nurses and business majors and scientists and poets need philosophy, too. I think that studying philosophy will make you a better nurse, one more able to improve the nursing profession and to improve your workplace.

And let me add one more thing. When you came into my office the other day to ask me that brilliant question, one thing was quite clear to me: whether or not you choose to make philosophy your formal major, you are already becoming a philosopher. And that makes me very happy indeed.

Because "Liberal" in "Liberal Arts" Means "Free"

Martha Nussbaum, Not For Profit: Why Democracy Needs The Humanities. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010) p. 21.

Three Words About Writing: Plato, Emerson, Bugbee

(To paraphrase Thoreau, there are nowadays plenty of philosophy professors, but not so many lovers of wisdom.)

Instead, I offered a reflection on three ideas that matter for me as I write. Here are three that I keep coming back to:

First, a word from Plato: "Follow the argument wherever it leads." And try to find good interlocutors. If you surround yourself with people who say "yes" to everything you say, your writing and your thinking will both atrophy. If the trail leads uphill, it's no good to stay on the level path. Plato seems to have used writing as a way of sketching out how one might begin to solve problems. He didn't give answers so much as good questions. His dialogues survive because they are such good invitations for us to try to work out the solutions ourselves.

Second, Emerson: Your journals are your savings accounts. Your life is the way you earn deposits. "If it were only for a vocabulary the scholar would be covetous of action," he wrote. "Life is our dictionary." Without action, there is no experience; and without experience, the writer's vocabulary becomes continually narrower. Emerson wrote in fragments - very short essays, or sentences - in his journals, and when he sat down to write his essays and lectures, he found those fragments to be a rich vein of inspiration and even of finished work.

Finally, Bugbee: "Get it down." Write forward; don't edit too much. Keep writing, and as much as possible, write the way it comes. Attend to experience as it is given, without trying too hard to color it or shape it. Practice seeing, and seeing honestly, and write what you see.

This isn't by any means a whole course in writing, but it is a place to start. And often, that's what writers need: to start.

Then keep writing.

Popper On The Gift Of Wonder

-- Karl Popper, “The Nature of Philosophical Problems,” in Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge. (Routledge, 2002) 95. (Boldface emphasis mine.)

Do Birds Need Ornithologists?

|

| Cooper's hawk in my backyard. |

Feynman was just talking about philosophers of science, which is just one narrow slice of the philosophic pie. More recently others, like Freeman Dyson, have made broader indictments of philosophy, or like Lawrence Krauss, of the humanities generally.

Dyson, in an article he wrote for the New York Review of Books, described today's philosophers as "a sorry bunch of dwarfs. They are thinking deep thoughts and giving scholarly lectures to academic audiences, but hardly anybody in the world outside is listening. They are historically insignificant." Yes, we have a technical vocabulary that outsiders often have trouble understanding. But that's true of every discipline. And yes, we don't seem to have anyone in our discipline who is writing the next Job or Republic right now, but that's been true almost always. No discipline consistently produces nothing but geniuses. Many of us in every discipline live our careers out bearing the gifts of the past forward to another generation so that they might benefit from them and add to them. And many of us are content to be forgotten as long as the books of wisdom entrusted to us are remembered.

|

| Female ruby-throated hummingbird. |

In his recent book A Universe From Nothing, Krauss seems to be at pains to point out that without the sciences, the humanities are virtually useless, and that even with the sciences, the humanities are still virtually useless. His introduction pushes the humanities back at arm's length and invites them to clear out while science handles all the real heavy lifting.

What stands out for me as I read these scientists and some others writing in a similar vein is that they write like they're on the defensive and feeling embattled. My guess is that they see themselves or their disciplines as being engaged in an important fight about cultural values, science education, and research funding. The outsized reaction to Thomas Nagel's recent Mind and Cosmos - with its inflammatory subtitle, "Why The Materialist Neo-Darwinian Conception of Nature Is Almost Certainly False" - suggests that many advocates of the sciences worry about any book that might give comfort to the enemy.

|

| Mourning dove eggs in one of my flower pots. |

I should add that philosophers like me benefit from ornithologists, too. I am especially grateful for the ornithologists at Cornell University for putting so much helpful information on their website for bird-watchers and ornithophiles like me.

The bird I have identified as a Cooper's hawk might be a sharp-shinned hawk; I often have trouble distinguishing them. We live on the migration path for ruby-throated hummingbirds, so we see them for two brief seasons, once in the spring and again in the fall. Mourning doves are notoriously poor parents, and we often find they've laid eggs in silly places. Fortunately for their species, they can produce multiple clutches each year.

If you're interested in both birds and philosophy, let me recommend Charles Hartshorne's book Why Birds Sing. Hartshorne suggests that maybe birds sing because they enjoy it. This may seem so obvious as to be silly, but it is a helpful addition to the usual claims that birds sing because singing is useful for mating, staking territorial claims, self-defense, and so on. Hartshorne doesn't allow us to reduce birds to bird-making machines. Which is helpful, because it's a reminder that we, too, are more than human-making machines. It's also good to be reminded that it's okay to sing for the sheer enjoyment of singing.

What Philosophers Do

I think this is because most people I meet don't know what philosophy is, or what one does with it. So when I say what I do, they aren't sure what to say next.

So let me tell you what I do: I ask questions, and I teach others how to do that.*

You could say I'm a professional trainer of skeptics. I train people in curiosity. My aim is to be like a child again in front of big ideas, and to show my students that it's alright to indulge in a little wonder.

Because we don't just learn by being given good answers; more than anything, we learn by asking good questions.

* By the way, it's a fair question to ask if you want to know how I do that.

And it's also fair to notice that by suggesting that you ask that question I've just given you a little example of what I do.

Philosophy Begins in Wonder

It has since been noted that philosophy aims at the conclusion of wonder. This, unlike the first statement, might not be correct.

So much depends on what we understand the aim of philosophy to be. If we model it on the applied sciences, then its aim is to solve particular problems, in which case it aims to be done with its work. The conclusion of a chain of reasoning becomes its consummation, and the consummation becomes the end.

But if philosophy should also aim to make us scientists as Peirce understood science - he says it is "the pursuit of those who desire to find things out" and something that is carried out in a community, not by an isolated individual - then it aims not just at solving problems but at introducing us to the world.

Bugbee points out (Inward Morning, August 31 entry) that in wonder, "reality has begun to sink into us." Think about it: when you really wonder at something, isn't it because of a disclosure? Wonder may seem to concern what is hidden, but the beginning of wonder is also the beginning of an opening, when the world opens to us. If it were not so, we would not even know to wonder.

Philosophy teaches us - or ought to teach us - to open ourselves in return. This opening of ourselves is not the conclusion of wonder but the development of the habit of wonder. I don't mean the slack-jawed laziness that poses as wonder and pretends that all things are wonderful while being open to none of them, but, as Bugbee puts it, a commitment to being in the wilderness and the patience to let ourselves be "overtaken...by that which can make us at home in this condition."

Bugbee and the Tillage of the Soul

In the opening entry of The Inward Morning, Henry Bugbee writes

Wittgenstein, contra Hawking

“Philosophy has made no progress? If somebody scratches where it itches, does that count as progress? If not, does that mean it wasn’t an authentic scratch? Not an authentic itch? Couldn’t this response to the stimulus go on for a long time until a remedy for itching is found?”

On Writing Philosophy Essays

Writing a philosophy paper? Here are a few phrases you should probably avoid:

1) “Socrates* feels that X is true." (We don’t know much about his feelings, do we? Focus on what he said rather than on what you think he felt, unless you’re also prepared to explain your insight into his feelings, and the relevance of that insight and of those feelings.) (*Or any other philosopher who doesn’t tell us how she is feeling.)

2) “There is no answer to this question.” (Do you mean no correct answer? Why do you think I asked it, by the way? Let me suggest that, at a minimum, there is an answer given in the texts we read. If you think it’s wrong, I’d be delighted to hear why you think it’s wrong, once you’ve told me clearly what it is.)

3) “I’ve decided to ignore what the books say and focus on my own opinions here.” (Not that your opinions don’t matter, but they’re deucedly difficult to grade.)

Do Philosophy Classes Have "Labs"?

When I was preparing to go to grad school I was torn between two choices: Ph.D. in marine/riparian biology, or Ph.D. in philosophy? I love fish, aquatic invertebrates,

(well, most of them, anyway) and the environments they live in. Wouldn't it be great to make freestone streams and tidal pools into my classrooms?

But I also love philosophy. Philosophy has connections to every other discipline; it offers a unique perspective on human activities; and it promotes some of the most interesting and fruitful conversations I know of. (Yes, I admit some professional bias here, and don't begrudge others a similar bias towards what they love.) Philosophy classes take on questions about truth, value, meaning, religion, justice, science, language, reason, history, relationships, and much more. It can be very difficult, but there's usually a huge payoff for the effort you put into it.

Now that I teach philosophy, I often find myself lurking around the biology department at my school, to read their journals, to talk with the professors there (who patiently put up with my presence there), and to eye their labs with envy.

Now, I think bio labs are great places, but it's not the places themselves that I most like. It's rather the idea of the place. Labs are spaces set apart for learning by experience. We have labs for the sciences, and we have labs for the arts as well (though we usually call those "studios"). In the social sciences they use labs for observing human activities, and foreign languages have (or ought to have) labs for practicing language. Writers have workshops, historians have museums and archives, and other disciplines have internships.

Philosophy, unlike all these other disciplines, does not appear to have any labs at all. At least, not at first glance.

Partly this is due to the reflective nature of philosophy: philosophers have often understood our discipline as a step back from experience in order to gain a cool, disinterested view of the world. To some degree, we still think that, but that idea of having a privileged access to reality through the use of the right kind of language, or through a scientific worldview, has fallen under suspicion. Pace Descartes, we don't necessarily understand the world better by turning completely away from it.

Contrary to popular opinion, "philosophy" is not a synonym for "opinion." Nor is it a synonym for "doctrines." Philosophy has grown and changed quite a lot in the last few centuries, which means that is not always easy to define. One thing that is common to all philosophers, however, is that philosophy is an activity. Doing philosophy is not the mere rehearsal of past views, nor is it merely an attempt to present our already established opinions in clearer or more persuasive language.

Philosophers do, in fact, set aside spaces and times for practicing philosophy. One important kind of lab philosophers have is the seminar, which has its roots in Plato's practice of philosophy. Whatever else we might say about Plato, he knew how important good conversation is to advancing philosophy. In his dialogues, Plato uses conversation to illustrate two points: first, we need to spend at least some of our time in serious, sustained conversation and reflection with others. Second, when we do so, we need to follow the argument where it leads and not just where we want it to go.

|

| A brook trout I photographed in Maine. |

*********************

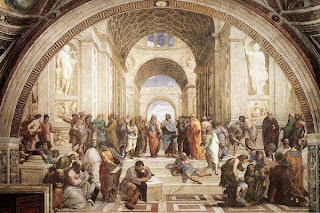

[Images: Raphael's "School of Athens," showing famous Greek philosophers "at work"; two mayflies photgraphed in the summer of 2009 in Gravenhurst, Ontario; one of the tributaries to Lake Muskoka in Ontario; a brook trout photographed on the Magalloway River in Maine, 2009 while fishing and doing some research with Matt Dickerson. The Raphael image is in the public domain; the others are my own photos. I think mayflies are especially lovely creatures. The adult stage shown above is a very brief period of their lives; most of their lives are spent underwater, and their appearance is quite different then from what it is as adults.]