Plutarch

∞

A Pretty Good Year

Last year was a pretty good year. Or at least, what I remember of it was pretty good.

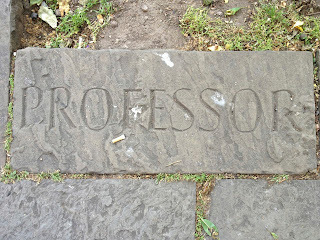

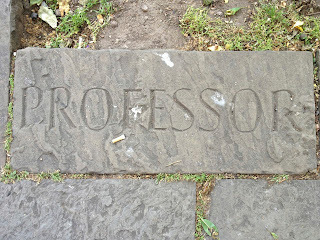

As my regular readers know, I'm a professor of philosophy and classics, and I teach a wide range of classes. (You can click on the "Teaching" link above to see a sampling of the courses I teach.)

Often people assume that means I wear tweed and a bowtie and that I spend my time in classrooms talking about old books. All that is true, but it's only a part of what I do.

In fact, most of my favorite classrooms are outdoors, where I'm likely to be found wearing jeans and hiking boots, a parka, or a wetsuit and snorkel.

Over the last dozen years or so my teaching and research have tended towards the environmental humanities. Think of this as the merging of the humanities side of the liberal arts with a close observation of the natural world. I consider my work to be a continuation of the work that Thales and Aristotle did when they paid close attention to animals on the ground and to the skies above, and of the work of Peirce, Thoreau, and Bugbee, all of whom let a rising trout or a solar eclipse provoke philosophical reflection.

While I don't work in an indoor laboratory, I think that education is not about the imparting of information or the filling of an empty vessel with ideas. Education is the kindling of a fire, as Plutarch wrote. And that fire is kindled by the kinds of experiences that we get in labs, art studios, shared meals, liturgies, study travel, and seminars. Lecture halls are a fine place to discuss environmental policy, to be sure. But so is a prairie, especially when you're waiting for water to boil on your camp stove, and watching the sun's beams break over the horizon and melt a light frost on your tent.

When I'm at home, I like to take my classes outside to sit under trees on campus. In the fall, I try to bring my Ancient Philosophy students camping in the Badlands of South Dakota where we can view the stars far from urban glow. Most Januaries, my students and I are in the subtropical forests of Guatemala and on a barrier island in Belize, studying ecology and culture. I rarely take a spring break, since I usually take that week to teach a course in Greece. Last summer I started teaching a class on trout and salmon in Alaska.

Those are all beautiful, memorable places, but I don't visit them as a tourist. I go to these places because I want my students to understand what is at stake when we talk about environmental regulations and practices. I want them to meet displaced people whose permafrost islands are melting or whose forests are being burned down for meager cropland. I want them to see the disappearing mangroves so that they can consider the full cost of seafood. When they stay in homes in Guatemala, my students will meet people who can never again be a mere abstraction; after we return, my students will know that the people struggling to cross borders are not nameless, faceless strangers, but people who are looking for ways to feed those they love.

A little less than a year ago I was finishing up a year that had brought me to all these places. I taught in the South Dakota Badlands, in Central America, in Greece, and in Alaska. Along the way, I had begun studying environmental law at Vermont Law School as a way of enhancing my teaching and my research. It was a good year, and as August was winding down, my desk was covered with field notebooks full of observations from Alaska and Guatemala, ready to be written up. My field notes are usually accompanied by thousands of photographs, and hundreds of sketches. I began the fall semester last year ready to teach, and ready to write.

And then I wound up in the hospital with some serious injuries. Those injuries put a sudden stop to all my teaching last fall, and for a long time I lost most of my ability to write. (I'll try to write more about the injuries and my subsequent disabilities later; it's not an easy thing to write about yet.)

Now, as this summer hastens towards the beginning of another school year, I am able to look back on last year with a sense of good fortune - albeit mixed with one very bad day and its long-term consequences. Physically, I'm regaining my flexibility and strength, a little at a time. I'm not where I was a year ago, and I may never be there again, but I'm alive and able to walk, so I'll count that in the "win" column of my life's scorecard. Intellectually, most people seem to think I'm doing fine, so I'll also count that as a win. Although it left me exhausted each day, I was able to teach again this spring, and I plan to be back in my classrooms (Deo volente!) this fall.

But here are these field notebooks, and hundreds of unedited pages on my hard drive. It was my habit to write daily. Over the last year, recovering from a brain injury has made it hard to write more than a few sentences at a time.

This morning I was looking at some of my pictures from my research in the Arctic last summer, and I was hit with a feeling of loss. Those photos and those notes should be a book by now, and perhaps several articles and book chapters, too. Instead, over the last year, as I have waited for my body and brain to heal, and as I struggled to do my teaching, I had no strength to write.

It feels funny to say that, but perhaps I am not alone in finding that a brain injury can be slow to heal and extremely tiring. I don't say that to get your sympathy. I am blessed with a very supportive community and an amazing wife who somehow has kept our life together and nursed me through my healing process. I'm fortunate. But if you've read this far, you might consider whether there are others around you who look like they're doing well physically but who might be nursing invisible wounds or who might be struggling to cope with invisible disabilities. This past year has given me a new perspective on that by making me aware of my own disabilities, most of which you won't notice if you see me at the gym or in one of my classrooms.

I might not be able to write another book yet, so for now, here's my plan: I'll write a little at a time. Thankfully, I've got my notes, sketches, and photos. I'll start with them.

If you're curious about how a professor of philosophy and classics does research and writing about nature - and how he works to recover from a serious brain injury - you might check out some of my recent publications. My book Downstream is the result of eight years of field research on the ecology of the Appalachians, with a focus on brook trout. On this blog you'll also find my recently published poem, "Sage Creek," which might give you a glimpse of my ancient philosophy class camping and stargazing in the Badlands. Or feel free to look at my photos on Instagram. Even when I can't teach in the field, I can still wander my garden with a hand lens and camera.

As my regular readers know, I'm a professor of philosophy and classics, and I teach a wide range of classes. (You can click on the "Teaching" link above to see a sampling of the courses I teach.)

Often people assume that means I wear tweed and a bowtie and that I spend my time in classrooms talking about old books. All that is true, but it's only a part of what I do.

In fact, most of my favorite classrooms are outdoors, where I'm likely to be found wearing jeans and hiking boots, a parka, or a wetsuit and snorkel.

Over the last dozen years or so my teaching and research have tended towards the environmental humanities. Think of this as the merging of the humanities side of the liberal arts with a close observation of the natural world. I consider my work to be a continuation of the work that Thales and Aristotle did when they paid close attention to animals on the ground and to the skies above, and of the work of Peirce, Thoreau, and Bugbee, all of whom let a rising trout or a solar eclipse provoke philosophical reflection.

While I don't work in an indoor laboratory, I think that education is not about the imparting of information or the filling of an empty vessel with ideas. Education is the kindling of a fire, as Plutarch wrote. And that fire is kindled by the kinds of experiences that we get in labs, art studios, shared meals, liturgies, study travel, and seminars. Lecture halls are a fine place to discuss environmental policy, to be sure. But so is a prairie, especially when you're waiting for water to boil on your camp stove, and watching the sun's beams break over the horizon and melt a light frost on your tent.

When I'm at home, I like to take my classes outside to sit under trees on campus. In the fall, I try to bring my Ancient Philosophy students camping in the Badlands of South Dakota where we can view the stars far from urban glow. Most Januaries, my students and I are in the subtropical forests of Guatemala and on a barrier island in Belize, studying ecology and culture. I rarely take a spring break, since I usually take that week to teach a course in Greece. Last summer I started teaching a class on trout and salmon in Alaska.

Those are all beautiful, memorable places, but I don't visit them as a tourist. I go to these places because I want my students to understand what is at stake when we talk about environmental regulations and practices. I want them to meet displaced people whose permafrost islands are melting or whose forests are being burned down for meager cropland. I want them to see the disappearing mangroves so that they can consider the full cost of seafood. When they stay in homes in Guatemala, my students will meet people who can never again be a mere abstraction; after we return, my students will know that the people struggling to cross borders are not nameless, faceless strangers, but people who are looking for ways to feed those they love.

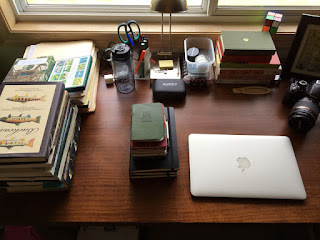

A little less than a year ago I was finishing up a year that had brought me to all these places. I taught in the South Dakota Badlands, in Central America, in Greece, and in Alaska. Along the way, I had begun studying environmental law at Vermont Law School as a way of enhancing my teaching and my research. It was a good year, and as August was winding down, my desk was covered with field notebooks full of observations from Alaska and Guatemala, ready to be written up. My field notes are usually accompanied by thousands of photographs, and hundreds of sketches. I began the fall semester last year ready to teach, and ready to write.

|

| Field notes. A picture of some of the work I do when I'm inside, and not teaching; or, if you like, a picture of my desk as I recover from my injuries. I have a lot of catching up to do. |

And then I wound up in the hospital with some serious injuries. Those injuries put a sudden stop to all my teaching last fall, and for a long time I lost most of my ability to write. (I'll try to write more about the injuries and my subsequent disabilities later; it's not an easy thing to write about yet.)

Now, as this summer hastens towards the beginning of another school year, I am able to look back on last year with a sense of good fortune - albeit mixed with one very bad day and its long-term consequences. Physically, I'm regaining my flexibility and strength, a little at a time. I'm not where I was a year ago, and I may never be there again, but I'm alive and able to walk, so I'll count that in the "win" column of my life's scorecard. Intellectually, most people seem to think I'm doing fine, so I'll also count that as a win. Although it left me exhausted each day, I was able to teach again this spring, and I plan to be back in my classrooms (Deo volente!) this fall.

But here are these field notebooks, and hundreds of unedited pages on my hard drive. It was my habit to write daily. Over the last year, recovering from a brain injury has made it hard to write more than a few sentences at a time.

This morning I was looking at some of my pictures from my research in the Arctic last summer, and I was hit with a feeling of loss. Those photos and those notes should be a book by now, and perhaps several articles and book chapters, too. Instead, over the last year, as I have waited for my body and brain to heal, and as I struggled to do my teaching, I had no strength to write.

It feels funny to say that, but perhaps I am not alone in finding that a brain injury can be slow to heal and extremely tiring. I don't say that to get your sympathy. I am blessed with a very supportive community and an amazing wife who somehow has kept our life together and nursed me through my healing process. I'm fortunate. But if you've read this far, you might consider whether there are others around you who look like they're doing well physically but who might be nursing invisible wounds or who might be struggling to cope with invisible disabilities. This past year has given me a new perspective on that by making me aware of my own disabilities, most of which you won't notice if you see me at the gym or in one of my classrooms.

I might not be able to write another book yet, so for now, here's my plan: I'll write a little at a time. Thankfully, I've got my notes, sketches, and photos. I'll start with them.

If you're curious about how a professor of philosophy and classics does research and writing about nature - and how he works to recover from a serious brain injury - you might check out some of my recent publications. My book Downstream is the result of eight years of field research on the ecology of the Appalachians, with a focus on brook trout. On this blog you'll also find my recently published poem, "Sage Creek," which might give you a glimpse of my ancient philosophy class camping and stargazing in the Badlands. Or feel free to look at my photos on Instagram. Even when I can't teach in the field, I can still wander my garden with a hand lens and camera.

∞

Back To Work

Restful Work

I've been on sabbatical for the last academic year, and it has been a gift.

I've done a lot of writing (I think I've averaged about 750 words a day, which may not sound like much, but it is) and a lot of reading (roughly a half a book a day for fifteen months) and a lot of traveling (visited five countries; had one writing fellowship on the west coast and one NEH study fellowship on the east coast; read and wrote at a writer's conference in Vermont; attended a handful of other conferences; and a whole lot more. I lived out of my suitcase for the first two months of this summer.)

In other words, my sabbatical hasn't been idle time. Quite the opposite.

But now I'm ready to get back to work. To the work I feel called to do, that is. All the work I've done for the last year has been aimed at a particular purpose: to make me a better teacher.

Those Who Can, Teach

No doubt you've heard it said that "those who can, do; those who can't, teach." Anyone who has tried to teach well knows exactly why that saying is false.

In one small way, it can sometimes be true: it may be that the teacher lacks the physical capability to perform the tasks she teaches. But if she teaches them, she must understand them at least as well as those who perform them. Good athletic coaches illustrate this idea well: a man may be a brilliant football coach well after he's too old to survive being tackled; a woman may understand her sport far better after her body will no longer allow her to participate in it.

But in each case it is obvious that the teacher has some mastery that is greater than the bodily capacity to do the activity.

To paraphrase Aristotle: the craftsman knows something, but the one who teaches the craftsman must know even more. My sabbatical has been a chance to deepen precisely the kind of knowledge I need to be a good teacher.

Be The Change You Want To See In Your Students

I can't speak for all teachers, but I find that it is not enough to know only as much as I plan to teach. When I teach a course in philosophy, philology, theology, ecology, or history I must become a student of that discipline myself.

This is one of the reasons why humanities professors are always reading and writing. It is not enough to tell the students what we know. As Plutarch put it, "The mind is not a vessel to be filled but a fire to be kindled." My job is not to impart information; my job is to make students. My job is the work of conversion, of helping people become what they were not, of facilitating the habit of learning throughout one's whole life.

To put it negatively, my job is to avoid being a hypocrite. More positively, my job is to be an example of the kind of change I wish to see in my students. And this is why sabbaticals are so important. They are not a reward for service, a respite from the work of teaching. They are a chance to immerse oneself in the life of the student again, to strengthen the scholarly habits. Sabbaticals make better teachers.

Looking Forward To My Real Work

Recently I was having a drink with some other professors in my field as we sat on a hotel rooftop in Athens. Several of them described the tricks they've come up with to minimize grading and teaching, so that they can spend more time on their "real work." This "real work" turned out to be their research.

Recently I was having a drink with some other professors in my field as we sat on a hotel rooftop in Athens. Several of them described the tricks they've come up with to minimize grading and teaching, so that they can spend more time on their "real work." This "real work" turned out to be their research.

Kvetching in bars is a popular pastime for many professions, so I won't hold those words against them. And I can't claim to know what the difficulties of their lives are like, nor how hard it is for them to manage the stresses of the job market (neither of them has a stable position). And both of them may in fact be excellent researchers who are producing books and articles the world needs.

But it made me sad to hear that things have so fallen out for them that they have come to regard teaching as an impediment to their real work. I love teaching, and I'm grateful for the privilege of spending time with books and pens and bright young minds. I love the way the books and pens become tools for working out our life together.

Some of my friends have been ribbing me about having to go back to work after a yearlong sabbatical. I'm sure it will present some challenges, and I'll have less control of my schedule. But honestly, I've missed the classroom. This year has been like time in the shop, taking apart the engine and replacing worn parts, topping off the fluids, recharging the battery. As the sabbatical comes to a end, I find I'm eager to rev the engine and step on the pedal. I'm looking forward to seeing my older students, and to meeting the new ones. I'm looking forward to engaging in the lofty work I've been called to, of helping young people think in ways they had not yet imagined. I'm looking forward to seeing their eyes light up as they read Plato and Kant and Emerson, to hearing their challenges, to seeing what happens when they, too, step on the pedal and squeal the tires. I can't wait to get back to work.

*****

If you're curious: The Plutarch quote, above, comes from near the end of his "On Listening To Lectures." This is my rough translation, which I think comes pretty close to what he says.

I've been on sabbatical for the last academic year, and it has been a gift.

I've done a lot of writing (I think I've averaged about 750 words a day, which may not sound like much, but it is) and a lot of reading (roughly a half a book a day for fifteen months) and a lot of traveling (visited five countries; had one writing fellowship on the west coast and one NEH study fellowship on the east coast; read and wrote at a writer's conference in Vermont; attended a handful of other conferences; and a whole lot more. I lived out of my suitcase for the first two months of this summer.)

In other words, my sabbatical hasn't been idle time. Quite the opposite.

But now I'm ready to get back to work. To the work I feel called to do, that is. All the work I've done for the last year has been aimed at a particular purpose: to make me a better teacher.

Those Who Can, Teach

No doubt you've heard it said that "those who can, do; those who can't, teach." Anyone who has tried to teach well knows exactly why that saying is false.

In one small way, it can sometimes be true: it may be that the teacher lacks the physical capability to perform the tasks she teaches. But if she teaches them, she must understand them at least as well as those who perform them. Good athletic coaches illustrate this idea well: a man may be a brilliant football coach well after he's too old to survive being tackled; a woman may understand her sport far better after her body will no longer allow her to participate in it.

But in each case it is obvious that the teacher has some mastery that is greater than the bodily capacity to do the activity.

To paraphrase Aristotle: the craftsman knows something, but the one who teaches the craftsman must know even more. My sabbatical has been a chance to deepen precisely the kind of knowledge I need to be a good teacher.

Be The Change You Want To See In Your Students

I can't speak for all teachers, but I find that it is not enough to know only as much as I plan to teach. When I teach a course in philosophy, philology, theology, ecology, or history I must become a student of that discipline myself.

This is one of the reasons why humanities professors are always reading and writing. It is not enough to tell the students what we know. As Plutarch put it, "The mind is not a vessel to be filled but a fire to be kindled." My job is not to impart information; my job is to make students. My job is the work of conversion, of helping people become what they were not, of facilitating the habit of learning throughout one's whole life.

To put it negatively, my job is to avoid being a hypocrite. More positively, my job is to be an example of the kind of change I wish to see in my students. And this is why sabbaticals are so important. They are not a reward for service, a respite from the work of teaching. They are a chance to immerse oneself in the life of the student again, to strengthen the scholarly habits. Sabbaticals make better teachers.

Looking Forward To My Real Work

Recently I was having a drink with some other professors in my field as we sat on a hotel rooftop in Athens. Several of them described the tricks they've come up with to minimize grading and teaching, so that they can spend more time on their "real work." This "real work" turned out to be their research.

Recently I was having a drink with some other professors in my field as we sat on a hotel rooftop in Athens. Several of them described the tricks they've come up with to minimize grading and teaching, so that they can spend more time on their "real work." This "real work" turned out to be their research.Kvetching in bars is a popular pastime for many professions, so I won't hold those words against them. And I can't claim to know what the difficulties of their lives are like, nor how hard it is for them to manage the stresses of the job market (neither of them has a stable position). And both of them may in fact be excellent researchers who are producing books and articles the world needs.

But it made me sad to hear that things have so fallen out for them that they have come to regard teaching as an impediment to their real work. I love teaching, and I'm grateful for the privilege of spending time with books and pens and bright young minds. I love the way the books and pens become tools for working out our life together.

Some of my friends have been ribbing me about having to go back to work after a yearlong sabbatical. I'm sure it will present some challenges, and I'll have less control of my schedule. But honestly, I've missed the classroom. This year has been like time in the shop, taking apart the engine and replacing worn parts, topping off the fluids, recharging the battery. As the sabbatical comes to a end, I find I'm eager to rev the engine and step on the pedal. I'm looking forward to seeing my older students, and to meeting the new ones. I'm looking forward to engaging in the lofty work I've been called to, of helping young people think in ways they had not yet imagined. I'm looking forward to seeing their eyes light up as they read Plato and Kant and Emerson, to hearing their challenges, to seeing what happens when they, too, step on the pedal and squeal the tires. I can't wait to get back to work.

*****

If you're curious: The Plutarch quote, above, comes from near the end of his "On Listening To Lectures." This is my rough translation, which I think comes pretty close to what he says.

∞

Written On The Skin

One of the peculiar things about teaching Greek and knowing several other ancient languages is that people often come to me seeking help with tattoos.

A few years ago a student named Brian came to me and asked "How do you say 'Suck Less' in Greek?" Apparently this was a phrase that his running coach said to his team to inspire them to run better.

As crude as the phrase is, I was intrigued by the problem of translation. "In order to translate the phrase I'd have to know what you mean by it," I replied. I spent a little while explaining how it would be possible to say, for instance, that an infant should nurse less; or that one should inhale less strongly. Or, if you pursue the more colloquial usage of the verb "suck," you might decide that it refers to poor behavior or - ahem - to a kind of erotic pleasure-giving in which the giver is thought to be demeaned by the giving.

Eventually I made the case that if you want to say it in Classical Greek, it would make sense to say it in a way that attended to the use of words in that language, and pointed him to Plutarch's Sayings of Spartan Women as a source of pithy sayings about living and acting strenuously. Ever since I took my first Greek class with Eve Adler at Middlebury College years ago, I've liked the phrase η ταν η επι τας, (at the link above, see #16 under "Other Spartan Women"; click on the Greek flag to see the full Greek text) which is often translated "Come back with your shield or upon it," meaning "Act virtuously in battle; either die with your weapons or win with your weapons, but do not throw them away in order to win your life at the expense of your virtue." I like the Greek phrase for its Laconian pithiness.

Of course, that one didn't quite make sense for a runner, so I showed him another from the same collection, κατα βημα της αρετης μεμνησο, or "With every step, remember [your] virtue." ("Virtue" is not a perfect translation; you could translate it as "excellence" also.)

Three years have passed since that conversation with Brian, but a few months ago he tracked me down and showed me his tattoo, which I rather like:

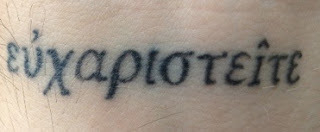

In a new twist, last year another student asked me to help him find the Greek verb "give thanks" as it appears in I Thessalonians 5.18. He didn't tell me what he planned to do with it, but when I saw him later that year at a wedding he showed me this, which he has tattooed on his wrist:

The word you see is ευχαριστειτε, related to our word "Eucharist" and the modern Greek ευχαριστω, meaning "I thank you."

I say this is a "new twist" because at least one passage in the Hebrew scriptures (Leviticus 19.28) appears to prohibit tattooing one's skin. Getting a tattoo, and in particular getting a tattoo of scripture, offers a bit of insight into one's hermeneutics. If the Gospels prohibited tattoos, I doubt many Christians would get them, but since the prohibition comes in the Hebrew scriptures, and since it seems to be tied to particular practices of worship or enslavement that no longer seem relevant, many young Christians are untroubled by it.

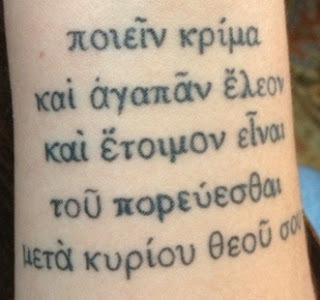

Recently one of my advisees showed me one of several tattoos she has recently acquired. This one is a longer Biblical text, from the prophet Micah, chapter 6, verse 8. I thought it interesting that she chose to get the Septuagint Greek rather than the Hebrew. She knows and translates Biblical (Koine) Greek and so I suppose she felt closer to that language. The text below means "...to do justice and to love mercy and to be ready/zealous to walk humbly with the Lord your God."

I like that verse quite a lot. If you don't know it, it begins by saying that this is what God asks of people. It's the sort of description that makes religion sound less like a burden and more like a description of a life well-lived.

I'm always reluctant to give advice about tattoos, because they're so permanent and so personal. And when I do give advice, I always want to write footnotes about regional dialects and historical and textual variants, or about the difficulties of translation. Quotes out of their native context so often seem lonely to me - such is my academic habit, of always seeing texts as living and moving and having their being* in nests and webs of other texts. Perhaps that's why I've never been inked myself, and I doubt I ever will get a "tat." I'm just not confident I've found words or an image that I'd want written on me forever. Sometimes that feels virtuous because it's prudent; other times I wonder if that's not a moral failing on my part, like I should be willing to commit to something. But I think for now I will remain uninked, and will continue to admire the commitments of my students.

* For example: I am borrowing this phrase ("live and move and have their being") from St Paul in Acts 17.28; he, in turn, appears to be borrowing it from Epimenides, who writes Εν αυτω γαρ ζωμεν και κινουμεθα και εσμεν. The phrase winds up being used in a number of other places, having been so eloquently translated into English by the King James Version of the Bible. See, for example, its use in the Book of Common Prayer, and in the first line of the hymn "We Come O Christ To Thee."

A few years ago a student named Brian came to me and asked "How do you say 'Suck Less' in Greek?" Apparently this was a phrase that his running coach said to his team to inspire them to run better.

As crude as the phrase is, I was intrigued by the problem of translation. "In order to translate the phrase I'd have to know what you mean by it," I replied. I spent a little while explaining how it would be possible to say, for instance, that an infant should nurse less; or that one should inhale less strongly. Or, if you pursue the more colloquial usage of the verb "suck," you might decide that it refers to poor behavior or - ahem - to a kind of erotic pleasure-giving in which the giver is thought to be demeaned by the giving.

Eventually I made the case that if you want to say it in Classical Greek, it would make sense to say it in a way that attended to the use of words in that language, and pointed him to Plutarch's Sayings of Spartan Women as a source of pithy sayings about living and acting strenuously. Ever since I took my first Greek class with Eve Adler at Middlebury College years ago, I've liked the phrase η ταν η επι τας, (at the link above, see #16 under "Other Spartan Women"; click on the Greek flag to see the full Greek text) which is often translated "Come back with your shield or upon it," meaning "Act virtuously in battle; either die with your weapons or win with your weapons, but do not throw them away in order to win your life at the expense of your virtue." I like the Greek phrase for its Laconian pithiness.

Of course, that one didn't quite make sense for a runner, so I showed him another from the same collection, κατα βημα της αρετης μεμνησο, or "With every step, remember [your] virtue." ("Virtue" is not a perfect translation; you could translate it as "excellence" also.)

Three years have passed since that conversation with Brian, but a few months ago he tracked me down and showed me his tattoo, which I rather like:

In a new twist, last year another student asked me to help him find the Greek verb "give thanks" as it appears in I Thessalonians 5.18. He didn't tell me what he planned to do with it, but when I saw him later that year at a wedding he showed me this, which he has tattooed on his wrist:

The word you see is ευχαριστειτε, related to our word "Eucharist" and the modern Greek ευχαριστω, meaning "I thank you."

I say this is a "new twist" because at least one passage in the Hebrew scriptures (Leviticus 19.28) appears to prohibit tattooing one's skin. Getting a tattoo, and in particular getting a tattoo of scripture, offers a bit of insight into one's hermeneutics. If the Gospels prohibited tattoos, I doubt many Christians would get them, but since the prohibition comes in the Hebrew scriptures, and since it seems to be tied to particular practices of worship or enslavement that no longer seem relevant, many young Christians are untroubled by it.

Recently one of my advisees showed me one of several tattoos she has recently acquired. This one is a longer Biblical text, from the prophet Micah, chapter 6, verse 8. I thought it interesting that she chose to get the Septuagint Greek rather than the Hebrew. She knows and translates Biblical (Koine) Greek and so I suppose she felt closer to that language. The text below means "...to do justice and to love mercy and to be ready/zealous to walk humbly with the Lord your God."

I like that verse quite a lot. If you don't know it, it begins by saying that this is what God asks of people. It's the sort of description that makes religion sound less like a burden and more like a description of a life well-lived.

I'm always reluctant to give advice about tattoos, because they're so permanent and so personal. And when I do give advice, I always want to write footnotes about regional dialects and historical and textual variants, or about the difficulties of translation. Quotes out of their native context so often seem lonely to me - such is my academic habit, of always seeing texts as living and moving and having their being* in nests and webs of other texts. Perhaps that's why I've never been inked myself, and I doubt I ever will get a "tat." I'm just not confident I've found words or an image that I'd want written on me forever. Sometimes that feels virtuous because it's prudent; other times I wonder if that's not a moral failing on my part, like I should be willing to commit to something. But I think for now I will remain uninked, and will continue to admire the commitments of my students.

*****

* For example: I am borrowing this phrase ("live and move and have their being") from St Paul in Acts 17.28; he, in turn, appears to be borrowing it from Epimenides, who writes Εν αυτω γαρ ζωμεν και κινουμεθα και εσμεν. The phrase winds up being used in a number of other places, having been so eloquently translated into English by the King James Version of the Bible. See, for example, its use in the Book of Common Prayer, and in the first line of the hymn "We Come O Christ To Thee."

*****

Update: a week or so after posting this I ran into the mother of one of the people whose tattoos are shown above. She thanked me, though I am not sure whether she was thanking me for helping her son get a tattoo, or for helping him to get the grammar right.

Contemplation, Conversation, Commentary

To paraphrase Plutarch’s famous line about education, the mind is not a vessel to be filled but a fire to be kindled. A jar that is filled by someone else only contains what is put into it; it becomes a place of storage. It is a useful tool, but it does not increase what it holds. A fire, on the other hand, gives off heat and light, and that heat and light can kindle other fires and illuminate distant obscurities.

I think education should be like this, a process that pays continual returns if it is well tended.

Of course, unchecked fire can do great harm, and education without boundaries is like a fire with no hearth or stove.

Should Education Have Boundaries? A Reflection On My Own Classrooms

But how can we put boundaries on education? One way, of course, is to limit education to memorization, tool-and-skill training, or indoctrination. But each of these amounts to filling a vessel. That is, it amounts to filling students’ minds with facts, opinions, or skills, without giving the students what they need to examine or improve what they are given, and to teach others what they have learned.

My aim as a teacher is to offer students liberal arts in such a way that they gain both practical skills and the means to improve those skills as the use and teach them. I say liberal arts because I do not wish my students to be the servants of others, but to be people who practice responsible liberty and who help others to do the same.

Of course, unchecked liberty can do great harm, and liberal education without boundaries is like a fire without a hearth. In one direction lies the restraint of being the mere vessel of others’ doctrines; in the other direction lie the perils of life beyond the bounds of ethics.

Fortunately, this is not a new problem, but a very old one. This means that there are some old and time-tested means of education that help us to find the mean between the extremes.

What I try to practice in my classes is something I see – in varying degrees – throughout the history of education. I will summarize it in three words: contemplation, conversation, and commentary.

Contemplation

By “contemplation” I mean the practice of examining what is already understood by the community of inquiry. What do we know? What are the tools we have at hand? What are the problems we wish to pursue together, and what solutions have been put forward so far? Learning these things is the first step, akin to learning the language when you move to a new country. It involves some memorization, and it involves learning the rules by which others conduct their lives and research. This is like learning the basics of a science, plus the methods used by scientists; or it is like learning the basics of poetry, plus the methods of reading and writing. Each discipline has its content and its tools, its history and its methods, its canonical texts and its rules and rituals for learning those texts. In my philosophy classes this means reading the assigned texts thoughtfully so that you come to class ready to ask good questions about them. In my language classes it means working through grammar and translation exercises, and memorization of vocabulary and inflections. In my environmental studies classes, this means learning basic taxonomy, ecology, geology, law, and policy, so you can discuss these things with others who know more than you do. In each discipline it will involve different things, but the general rule holds: if you want to join the community, you’ve got to learn these things first, just as you have to learn grammar before you can converse with others. And conversation is the next step.

Conversation

By “conversation” I mean coming together with others to think about the rules and tools we have been given. This is more than speaking with friends; this involves serious grappling with issues in the company of our contemporaries. In my philosophy classes, this means asking good questions about what you’ve read the night before class. It means exposing your ignorance and asking others to help you to correct it. It means taking others seriously as people who might see what is hidden in our blind spots. In my environmental humanities classes, this means going into the field with your classmates in order to examine the world together. In my philosophy of religion classes, this means engaging in the hard work of talking about the divine in a way that takes others seriously. Their questions might just be the questions you need; their insights might serve you well. It would be unwise to decide in advance that others have nothing to teach you; in each discipline, you’ve got to take time to do research, whether in the lab, in the field, in convivial conversation and deliberation with others. And then, when you’ve done that well, you’re ready to offer commentary on what your new insight means for us all.

Commentary

This is what I mean by “commentary,” then: the slow consideration of what consequences we might expect from what we have learned so far, and the offering of that consideration to others, so that they can contemplate and deliberate on them, and offer new commentary of their own.

Learning As A Cycle, And As A Shared Process

If you’ve done a good job with the first two steps, the third step leads you back to the first step. Good researchers who publish what they have learned contribute to the body of knowledge that others can use to kindle new fires that warm new homes and light new paths.

Another way of thinking about these three steps is that it concerns thinking about different times. The first step is the consideration of the past; the second involves taking seriously the present time and our contemporaries as fellow learners; and the third step is mindful of the future.

You might also think of this as a process of thinking at different speeds, and from different perspectives. The first step is often quite slow at first, and it requires us to learn to see as others saw, even if their way is not our own. The second step might happen quite quickly, whether in a sudden insight in the laboratory or in a fast-paced debate. The third step often requires the very slow work of painstakingly careful thinking and clear writing.

Of course, these three steps are not discrete. Often, they overlap and intermingle. We might discover in debate or in the field that we have failed to learn something important. Or our contemplative work might send us back to reexamine our research, or even to start over with new tools and insights. But on the whole, I think these three facets of learning wind up being repeated over and over in each field, and by connecting us to other people in the past, present, and the future, they offer a sort of bounded liberty to our learning.

Slow Thinking, Quick Writing, and Slow Assessment: On The Importance Of Self-Discipline

Much of what I hear and read about education has to do with metrics intended to assess the value of certain kinds of practices. I see the merit in many of those metrics. Sometimes, though, it seems that the metrics become a quick substitute for other kinds of evaluation that are harder to put into numerical or measurable form. We don't like the slow process of contemplation, or of commentary. We do like it when others put things in simple forms that we can quickly compare. There's value in that, but if we don't do our own contemplation and commentary, we abdicate a good deal of our involvement in our own learning, and we shift from being fires to vessels.

I am writing this piece fast, because I have a discipline of trying to write all my blog posts in less than fifteen minutes. (I do sometimes return to them to edit them for clarity or to add relevant information.) My aim here has been to write quickly about something I have thought about slowly. In other words, I've contemplated this for years, and today I'm writing a bit of quick commentary to contribute to our shared conversation. My quick writing is intended to be a moment of distillation of a cloud of contemplation. Too much time with my head in the clouds can obscure my vision; at some point I need those clouds to precipitate into more concrete thoughts. Writing helps me to do that.Your thoughtful replies and insights will hopefully help to kindle new fires.