Poetry

Poem: Visiting Rowan on Easter Sunday

Emma has been gone for a long time now.

Beside him, an electric photo frame shuffles images of his children and grandchildren and great-grandchildren,

All of whom keep him anchored here.

But he cannot eat, he says, as he holds a white plastic bag

With a blue plastic ring to hold it open for vomit.

We brought him a red egg, hard-boiled, in the Orthodox tradition.

He is glad to receive it with a sad smile,

But we both know he will not eat it.

Mother asks him if he would like communion, and he thinks;

Thinking is hard right now, and his eyes won’t focus

Though he tells us he can see through the doorway beyond

And make out the picture frame in the next room.

We turn to look but we don’t see it,

Unless he means the mirror, or the window, in the room across the hall

Or perhaps he sees something beyond our vision that we cannot yet see.

Richard is coming soon for lunch with his father,

Of course Rowan won’t eat, he tells us,

But he will be glad to see his son.

The phone rings. One of his daughters, calling to check in.

They all check in with me every day, he says,

With a laugh that makes him cough a little.

“They’re so good to me.”

He tells her he has guests, and that everything is fine.

The egg starts to roll off his lap, and he quickly catches it

With his knees, and it does not break.

Which reminds me that he learned to ski in his fifties

And only gave it up in his eighties when his balance started to go.

He hangs up the phone and Mother offers him communion once again.

He cannot focus his eyes, so we read the liturgy for him,

And then he takes the bread with fingers that have grown dark and thin and knurled like wild oak branches.

I am surprised by his speed and agility as he takes the bread.

And he chews it, and drinks the wine,

While his right hand clutches the white bag with the blue ring.

But he does not need to lift it to his lips.

The bread and the wine stay with him, and he laughs,

And stretches out a thin hand to each of us

And thanks us for coming to visit.

Would you like us to shut the door, Mother asks.

He is quick to reply:

No, please leave it open.

And he wishes us a happy Easter,

And we walk out through the lobby, where twenty gray heads in wheelchairs stare at the television screen, and wait.

One Word

One Word

One word to the finches

Who perch on my towering sunflowers,

Who fling golden petals,

Who drop a thousand husks

On the garden below.

Who dive at my coneflowers, talons out

And then peck and pull and shred

Those spiny, spiraled heads.

It is September now, but I know

That you and others of your kind

Will be back again, and again

Perching in the branches

All fall, and all winter too.

And you will continue to feast

On the dry seeds that remain.

What was a colorful garden is becoming

Your harvest meal, your stores for winter,

And you don't care how much I worked

To make this garden grow.

The earth I turned, the soil I amended,

The compost churned, the toil.

The seeds I raised inside while you sat

On brown stems, looking in my windows.

The seedlings planted, and watered,

And watched until they grew.

I have just one word for you:

Welcome.

When you leave today I'll gather

A few of those seeds myself

And I'll set them aside to dry

So that next spring you, and I

Can begin to grow again.

—-

David L. O'Hara

19 September 2020

On Paying Attention To Bear Poop - My recent TEDx talk in Fargo

The allegedly unnecessary things - like bear poop, and poetry - are often the things you most need to know.

I'm grateful to my friend Greg and his team for making this possible. I had no plans ever to do a TEDx talk until I met Greg through some mutual friends. We were having coffee here in Sioux Falls a few years ago, and I said something about the ecology of fish and forests. It must have resonated with Greg, because when I was done, he said "You should come to Fargo to give a TEDx talk!"

Some of the best things happen when you take time to have a cup of coffee or tea with friends, or when you meet new people, or when you find some bear scat on a trail by a river. Each of these things can be the prompting of a new thought, the spoor that shows you a new path.

The Ethics of Automation: Poetry and Robot Priests

In terms of ethics and law: who has access to the information confessed, and what is the legal status of that confession? Is there anything like the privilege of confidentiality enjoyed by clergy who hear private confessions from their parishioners?

“The making of things is in my heart from my own making by thee; and the child of little understanding that makes a play of the deeds of his father may do so without thought of mockery, but because he is the son of his father.”

Might it be possible for us also to make sentient life in imitation of God "without thought of mockery," and, if so, might it be that those lives we make could write poems and become priests? As anyone who has read Tolkien's myth knows, this raises a new set of ethical questions that now have to be resolved.--J.R.R. Tolkien, Silmarillion, p 43

*****

Update, 22 May 2018: Irina Raicu just published a very thoughtful reply to this, entitled "Parenting, Politeness, Poets, and Priests" at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University. Her article is very much worth the time it will take you to read it. You may find it here.

Bluejay Linings

stay together

learn the flowers

go light

Poem: Sage Creek

Here are the first few lines:

Halfway through the fall we drive west, far from urban glow,You can read it all here.

To see the stars that we have never seen at home.

We go to the Badlands, at night, to the primitive campground

And listen to the coyotes singing from rim to rim

Of the valley where we are trying to sleep.

The voices of three packs rise like questions:

Who are you? What are you doing here?

*****

Sage Creek

Halfway through the fall we drive west, far from urban glow,

To see the stars that we have never seen at home.

We go to the Badlands, at night, to the primitive campground

And listen to the coyotes singing from rim to rim

Of the valley where we are trying to sleep.

The voices of three packs rise like questions:

Who are you? What are you doing here?

Weary from driving, observe how much you want to stay awake

Now that you are here. Explain

And give examples

From all your senses.

If the wind blows across sage, then what follows,

and how do you first know it?

What is the feeling of the prairie wind at night,

And why is it now new to you?

Dry weeds crunch under sleeping bags stretched out under the cold, living sky.

Our arms swing to point at Orionid flares.

We speak in the whispers of worshipers entering a cathedral for the first time.

How long have we lived here,

On the prairie, and never felt it on our skin, all night long?

Compare and contrast

The Milky Way.

Before tonight, you have never seen it turn.

Consider all the stars,

And the difference between reading about them and watching them slowly slip across the sky.

Wake to the feeling that it is not yet dawn, but no longer night.

With your eyes still closed, ask yourself how you saw it,

How this dry land exposes you to yourself.

For a little while, you hold your eyes closed,

And remember the bright green lines of shooting stars.

Holding still, you listen:

This is the sound of bison, breathing. Nearby

The staccato chickadee and the whirling meadowlark

Greet the new day

In this place we have so long avoided.

The prairie dogs at the edge of the campground eye us warily, and bark a warning

As we load the car for the drive home.

*****

David L. O’Hara

(2015)

Printed in Written

River, Issue 10, 2016, Hiraeth Press.

The whole issue might be available on Kindle, here.

The Slow, Important Work Of Poetry

Without having a master plan, over four years I wound up taking a number of poetry classes in four languages. Eventually I asked my college to consider them a new minor area of study. They agreed, and I graduated.

And then, slowly, over a quarter century, I began reading more poetry in more languages. It's always slow; I can't pick up a book of poems and read it like a novel. If the poetry is any good at all, I can read one or two poems, and then I've got to put the book down and let the words sit with me.

Often, I go back and read the same poem again, and again.

The very best poems I try to memorize, even though my memory for verse has never been good. I imagine most people would consider that a useless exercise, a waste of storage space in an already cluttered brain.

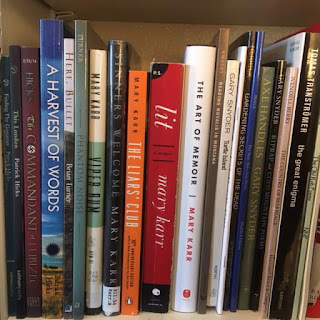

But in each season of my life I've found that it is some form of poetry that acts as salve to my soul's wounds or food that sustains its long journey forward. Homer's long story-poems; old epics and sagas from Ireland and Wales and Iceland; Vedic verses and Greek scriptures; Gregorian chants that have echoed in stone chambers for centuries; Shakespeare's or Petrarch's sonnets; the Psalms and proverbs of Hebrew priests and kings; a few words put together well by Dylan Thomas, Gary Snyder, Tomas Tranströmer, or C.S. Lewis; or the timely phrases of some of my favorite contemporaries like Patrick Hicks, Abigail Carroll, Mary Karr, Wendell Berry, Melissa Kwasny, John Lane, or Brian Turner. Each of them has, at some point, given me the daily bread I craved.

I can't seem to predict when the need will arise, but suddenly, there it is, and I find myself quoting Joachim du Bellay's sonnet about travel, and home:

Heureux qui, comme Ulysse, a fait un beau voyage

Ou comme cestuy-là qui conquit la toison

Et puis est retourné, plein d'usage et raison

Vivre entre ses parents le reste de son âgeHis simple words save me from forming new ones and free me to think and feel as the occasion demands; his words give utterance to what I find welling up inside me. His words change my homesickness into a stage in a worthwhile journey. Here is a very loose translation of those lines: "Happy is he who, like Ulysses, made a beautiful journey, or like that man who seized the Golden Fleece, and then traveled home again, full of wisdom, to live the rest of his life with his family." We are pulled in both directions at once: towards the Golden Fleece and adventures in Troy, and towards the home we left behind when we departed on our quest.

That sonnet often reminds me, in turn, of verses about Abraham.

Consider Abraham, who dwelled in tents,

because he was looking forward to a city with foundations.This longing for home that I sometimes have when I travel is itself no alien in any land. We all may feel it in any place. Everyone feels lost sometimes. Knowing that others have found words to express their feeling of being lost is itself a reminder that we are not alone. Hölderlin's opening words in his poem about St. John's exile on Patmos say this well:

Nah ist, und schwer zu fassen, der GottIt does seem that God - like home and family and love and neighbors - is close enough to grasp, so close that we could meaningfully touch them all right now. And yet so far that nothing but our words can draw near.

I am no good at praying, but I often wish I were. I think the fact that we make light of prayer - both by mocking those who pray and by being those who speak piously of prayer but who do not allow ourselves to confess the weakness prayer implies - says something of another shared longing, not unlike the longing for home. We long to comfort those far away when tragic events fall on them. They may be total strangers, but we know how horrible we would feel in their place, and we know that right now there is nothing we can do to staunch the flow of pain for them. But we can hold them in the center of our consciousness and, for a little while, not let any lesser thoughts crowd them out of our hearts and minds. We can, for a little while, consider our lives to be connected to theirs. We can, for a little while, ask ourselves what we might do to change the world so that this pain will not be inflicted on others.

Since I am not adept at praying, In those times I find the prayers of others buoy me up above the waves of emotional tempest. The prayer books of my tradition - the various versions of The Book of Common Prayer - often transform my anguish into something articulate. Of course, we turn to that same book when a baby is born, when a couple is wed, and when our beloved are interred. These events? We know they are coming, and yet it is not easy to prepare oneself, to be always ready for those days. I live in a tent; poetry often gives me a foundation to build on, and the better I've memorized it, the stronger that foundation becomes.

Those words, buried like seeds, slowly come to bear fruit in my life. Sometimes I wonder: was it really chance that brought me to the poems?

In the hardest of times, and also in the most joyful times, the words of poets are like a cup of water in a dry place. They refresh me, and they clear my throat so that I can take in that which sustains my own life, and speak other words, both old and new, that may sustain the lives of others.

The Importance of Struggling to Understand

"I don't like obscurity and obfuscation, but I do like dark sayings I must leave the clearing of to time. And I don't want to be robbed of the pleasure of fathoming depths for myself."

Robert Frost, "On Emerson." In Selected Prose of Robert Frost. Hyde Cox and Edward Connery Lathem, eds.(New York: Collier, 1968) p.114. (Originally delivered as an address to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences on the occasion of Frost's being awarded the Emerson-Thoreau Medal. Later published in Daedalus, Fall 1959.)I like Frost's use of "clearing" which still echoes the older meaning of "clear," that is "brighten." Frost's point is also excellent: simply explaining poetry, or great texts, to students is not enough. It is often helpful to guide them and to show them hermeneutical tools, or to speak with them about how we ourselves have grappled with texts, but we should be careful about the temptation to explain, since explanations can rob students of the pleasure of discovery. Poetry has immense value for us, and one -- just one -- of its benefits is the way that it can become the means by which we learn to solve problems that we have never encountered before.

Don't Worship The Monsters

"Killing the bodies of our enemies does not make them disappear. We must also choose to forgive them, in a refusal to let their violence rule our hearts. The alternative is to cherish their violence, silently fondling it in our minds and enshrining it in policies founded on fear."Last Advent I tried to say something similar, in a poem.

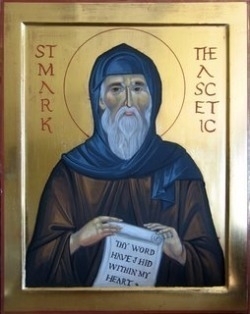

Hid In My Heart

On his blog, Kelly Dean Jolley has an icon of St Mark the Ascetic, or St Mark the Wrestler, that Jolley has kindly allowed me to include here. In his hands St Mark holds a scroll that reads "Thy word have I hid within my heart." Those words are from the 119th Psalm, a long poem about scripture.

When I was in college, my French professor Charles Nunley required me to memorize a new poem every week. Every week or two I'd go to his office and he would name one of the poems I'd learned and expect me to recite it, and then to discuss it. I'm not a great memorizer, so it was painful work, but I've been grateful for the discipline every year since then. It is a gift to have verses hidden in my heart.

When I was in college, my French professor Charles Nunley required me to memorize a new poem every week. Every week or two I'd go to his office and he would name one of the poems I'd learned and expect me to recite it, and then to discuss it. I'm not a great memorizer, so it was painful work, but I've been grateful for the discipline every year since then. It is a gift to have verses hidden in my heart.I am reminded of Mary, the mother of Jesus, when she heard what the shepherds were saying. Luke tells us that she "treasured these things in her heart," which I take to mean that she heard them, and then put them in that front room of her memory, the palm and fingertips of the mind where we touch and explore and consider ideas, turning them over and over again.

Well, this is what I do with treasured verses, anyway. Like I said, I'm a poor memorizer. But when I work at it, I hold the verses at mind's-eye level and gaze at them, running my inner eye down the length of them repeatedly, considering the way the grain moves and feeling the heft of the words until the grooves of my mind fit the notches of the words like a key. Because I hope that what I have hid in my heart will be like the Brothers Grimm's "Golden Key," which opens...well, I had better not tell you. Read it for yourself.

I wonder - when the great grinding erasure of time scrubs away at my memories, what will be left? What grooves in my grain will be too deep to scrape away? What treasures, what verses, what songs of my species will be buried too deep in my heart for the thief of time to steal?

Have We Met?

As it turns out, she has it even worse. When I greeted her, she asked me with her usual winning smile, "Have we met?" I told her we had, and where we had met. She said she had no recollection, and I thought she must be joking. Then she added that she has recently suffered a head injury and has lost her memory. She remembers that she once had such a powerful memory she was reluctant to tell people how much she remembered, lest she appear to be boasting.

Now she has very little of that memory left. She was cheerful, as always, but I thought maybe a little sad at what she had lost.

A little earlier in the day I had been speaking about C.S. Lewis and ecology to a church group. There I spent some time reflecting on a passage in Lewis's novel Out Of The Silent Planet where Hyoi cannot understand Ransom's culture. What kind of people would insist on having a pleasant experience again and again, Hyoi asks. Isn't that like wanting to hear a single word from a beautiful poem over and over, but not the whole poem? Isn't memory a part of the pleasure?

I have often taken comfort from that passage, since Hyoi's position is that growing old is not a loss but a gain, just as it is a gain to listen to a full symphony and not just the overture. Perhaps this is why we fear losing our memories: as the symphony of life approaches the finale sometimes we forget the overture.

As my former student turned to go, I told her "It's nice to meet you - again." She smiled, and walked away.

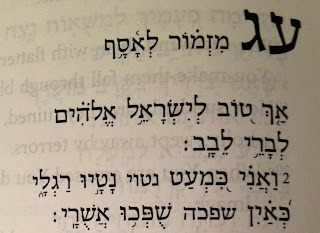

All Your Deeds

The last line caused me some trouble, though. In it Asaph, the psalmist, says "I will tell of all your [God's] deeds."

Okay, what exactly are those deeds? What can we ever reliably say about God's deeds? If God had done something in history that were not open to historical doubt, there would be no atheists.

The tradition gives us stories about God, and a century of biblical criticism calls those stories myths. Still, as I have argued elsewhere (here, and here, for example) myth is not - or should not be taken as - a synonym for falsehood. Stories may be myths and true, even if not historically true.

As Howard Wettstein argues in his Significance of Religious Experience,

The Bible’s characteristic mode of ‘theology’ is story telling, the stories overlaid with poetic language. Never does one find the sort of conceptually refined doctrinal propositions characteristic of a doctrinal approach. When the divine protagonist comes into view, we are not told much about his properties. Think about the divine perfections, the highly abstract omni-properties (omnipotence, omniscience, and the like), so dominant in medieval and post-medieval theology. One has to work very hard—too hard—to find even hints of these in the Biblical text. Instead of properties, perfection and the like the Bible speaks of God’s roles—father, king, friend, lover, judge, creator, and the like. Roles, as opposed to properties; this should give one pause. (108, emphasis added)The stories may not be about historical "deeds" but may be about the character, the roles of God.

Which makes me wonder: what roles does God play in my life? What "deeds" may I speak of?

|

| The preface to the complaint in Psalm 73 |

Before I reply, let me hasten to say this: I am often reluctant to write too strongly about this sort of thing because I do not want to say that others must believe what I believe. If God has led me to belief, (grant me that for the sake of argument for a moment) God has not strong-armed me into belief but allowed me to arrive at my beliefs over time, letting them be shaped by experience. I do not see why I should allow you less liberty than God has allowed me.

So I write the following admitting that I do not know what I am writing about. As Augustine confessed, when I speak of my love for God, I do so simultaneously wondering what I mean by "God." What can I compare God to? What is God like? I do not know how to answer those questions, except by telling stories, expositing roles. So here goes:

When I was a child, belief in God motivated a family in my neighborhood to care about me and to welcome me into their home when my family was falling apart. Without that love...I shudder to think what I would be today.

God gives me a name for what I pray to. God gives me a focal point for my attention in the vast cosmos, and God gives me a sense that in such a cosmos persons matter. And because persons matter, justice matters. This is not to say one cannot be just without belief, or that belief makes one just - far from it! - only that I find for myself the two ideas closely bound together.

God gives me solace in my mourning and hope when I pray. My mother is dead, but when I speak to God about her, she is not lost.

God gives me a story about the centrality of nurturing love. A reason to think all things are related. Someone to thank. Someone to be angry with. Rest for my soul. Quietness, and in it, trust.

God gives me a story about giving, and why giving and receiving should matter so much.

A story about why, and how, to turn a guilty conscience into repentance. A reason to forgive, and, very often, the strength to forgive. And to hope that I too am forgivable.

A reason to hope that no one is beyond redemption, beyond all hope, completely unworthy of love.

Belief that every person matters. More than that, belief that a teenage girl could be a vessel of the divine; that a third-world martyred prophet could save the world; that an inarticulate foreigner could be a world-historical lawgiver; that a persecuting zealot could get hit so hard by grace that he lives the rest of his life to preach good news for all people everywhere.

Hope that prison doors could be opened, that tongues could be loosed, that great art and great music might be signs of the divine.

I could be wrong about all of this, I know. I know there are other explanations of what I have written above. I also know those explanations apply to music, too, and I'm not interested in hearing about them there either if the reason for offering them is to help disabuse me of my love for good music. I know that people use the same word I use here to justify violence, self-interest, and hatred. I cannot help but feel angry and disgusted when it is used for those ends, ends which seem so contrary to what the word means for me, ends that make me think someone has read the wrong script, mis-cast the character, not known what deeds God has done.

Shakespeare's Sonnets, And Rieden's "Sonnet Number Six"

The Dean listened to all this patiently, and then made Charles an offer: write me one good sonnet and you don't have to read any of Shakespeare's sonnets. Charles immediately agreed. How hard could it be to write one decent sonnet?

Very hard, it turns out. And Charles, to his everlasting credit, came to see that pretty quickly. He produced some sonnets that week, but, by his own estimation, they were terrible. So he kept trying. Eventually, over the course of the next year, he had a thick stack of sonnets. I think in the end he wound up writing more sonnets than Shakespeare, and quite a few of them were really good.

Charles died, tragically, later that year. He was hit by a drunk driver as he walked along a highway in Santa Fe. The college framed one of his best sonnets, "Sonnet Number Six," and hung it in the graduate student common room.

As near as I know, it still hangs there, a memorial to Charles. I take it as a reminder not to dismiss too quickly what I do not understand, and not to imagine I understand what I have not really engaged with.

The Last Time I Saw Mingus

A Poem As I Approach Gaudete Sunday

Advent